A Mysticism for Our Time

September 1, 2017

By L. Roger Owens

Rediscovering the spiritual writings of Thomas R. Kelly

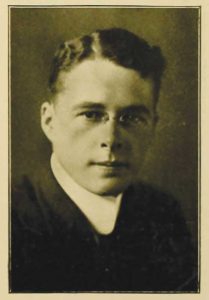

Thomas R. Kelly, “The Record of the Class of 1914.” Courtesy of Quaker and Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, Pa.

Thomas R. Kelly, “The Record of the Class of 1914.” Courtesy of Quaker and Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, Pa.While doing doctoral studies at Harvard in 1931, Thomas R. Kelly, a Quaker and author of the spiritual classic A Testament of Devotion, wrote to a friend and offered an assessment of famed British mathematician Bertrand Russell. He said that Russell seemed to him like an “intellectual monastic,” fleeing to the safety of pure logic to avoid the “infections of active existence” and the “sordid rough-and-tumble of life.”

When studying the papers of Kelly at Haverford College outside of Philadelphia, cocooned in the safety of the library’s special collections room the week after the presidential election, I was struck by this remark about Russell. I realized that many have leveled the same charge against mystics like Kelly himself. They are the ones, the story goes, who flee into an interior world of spiritual experience to escape the rough-and-tumble of actual existence.

The suggestion is not unfounded. Kelly’s thinking about mysticism was carried out under the long shadow of psychologist and philosopher William James: Kelly worked with James’s understanding of mysticism as the experience of the solitary individual. Kelly was also writing in the period following Evelyn Underhill’s influential Mysticism—its twelfth edition published during the years he was at Harvard—in which she writes that introversion is the “characteristic mystic art” that aids a contemplative in the “withdrawal of attention from the external world.”

That Kelly might be branded, then, a guide to the experiences of the inner life alone seems reasonable. My research has caused me to rethink this assessment; now I see Kelly as a mystic whose life is one of commitment to the world, not escape from it. And he can be a resource for those of us searching for a worldly engaged spirituality.

Istarted reading Kelly when I was 32. I remember this when seeing the mark I made in the biographical introduction to A Testament of Devotion of what Kelly was doing when he was 32. Because I wanted to explore the inner life of prayer he wrote about and lived, I was as drawn to the story of his life as I was to his writings.

A lifelong Quaker, Kelly was academically ambitious, driven, convinced that success as an academic philosopher would ensure he mattered. He received a doctorate from Hartford Theological Seminary in 1924 and began teaching at Earlham College in Indiana. But he pined for the rarefied intellectual atmosphere and prestige of an elite East Coast college. In 1930 he began work on a second doctorate at Harvard, assuming this would be his ticket east. But when he appeared for the oral defense of his dissertation in 1937, he suffered an anxiety attack; his mind went blank. Harvard refused to let him try again.

This failure proved the turning point in his life. It thrust him into a deep depression; his wife feared he might be suicidal. It also occasioned his most profound mystical experience, and he emerged a few months later settled, having been, as he put it in a letter to his wife, “much shaken by an experience of Presence.”

His friend Douglas Steere, a colleague at Haverford where Kelly was teaching at the time (he made it back east), summarized how many perceived the fruit of Kelly’s experience: “[A] strained period in his life was over. He moved toward adequacy. A fissure in him seemed to close, cliffs caved in and filled a chasm, and what was divided grew together within him.”

Three years later Thomas Kelly, 47 years old, died suddenly while washing dishes. The essays published in A Testament of Devotion were written in those few years between the fissures closing and his death. He died not only a scholar who wrote about mysticism, but a mystic himself, who knew firsthand that experience of spiritual solitude purported to be the essence of religion.

Far from sinking into the solitude of mystical bliss after emerging into his new, centered life, he promptly made an exhausting three-month trip to Germany in the summer of 1938, where he lectured, gave talks at German Quaker meetings, and ministered to the Quakers there who were suffering under Hitler.

The purpose of Kelly’s trip to Germany was to deliver the annual Richard Cary Lecture at the yearly meeting of German Friends. His letters home detail his painstaking preparation. He met frequently with his translator, working through the manuscript for several hours a day to render it in German. In a tribute to Kelly that was sent to his wife following his death, his translator—a Quaker woman of Jewish ancestry—said that his presence and his message were what the German Friends needed in “a time of increasing anxiety and hopelessness.”

From the beginning of the lecture, Kelly’s florid language is on display: he comes across as an evangelist for mystical experience, the “inner presence of the Divine Life.” His purpose is to witness to the inner experience of this divine life, this “amazing, glorious, triumphant, and miraculously victorious way of life.” He’s not offering an argument for it, or a psychology of it, following James, but a description resting upon experience.

Importantly, early on, he rejects any notion that this is a merely otherworldly experience. (In the published version of this lecture more than 20 years after its delivery, Kelly’s son cut out this section, maybe because it’s technically denser than the rest or maybe because it didn’t fit the mold of relevance for spiritual writing.) Kelly believed that the Social Gospel Movement of his time had too narrow a horizon, having bracketed out the persuading, wooing power of the Eternal. It is the one place, he noted, that he agrees with theologian Karl Barth. On the other hand, the experience he’s describing does not issue in withdrawal or flight from the world. “For,” as he puts it, “the Eternal is in Time, breaking into Time, underlying Time.” In fact, the mystical opening to an eternal “Beyond” opens simultaneously to a second beyond: “the world of earthly need and pain and joy and beauty.” There is no either-or.

This is precisely the place where Kelly’s experience makes all the difference. His weeks in Germany brought him into contact with many Quakers. He saw how they were at once struggling to live under the Nazi regime in fear, anxiety, and material want while also serving their suffering neighbors.

We learn this in a 22-page letter he wrote near the end of his trip. (Kelly spent two days in France in order to write and send home this frank letter describing the situation in Germany, fearing his letters sent from Germany were being read.) He notes in the letter that though Germany is “spruced up, slicked up,” its soul echoes hollow. If you were not a Nazi, you were always afraid, he wrote, because there’s “no law by which the police are governed.” He expresses amazement at the difficulty of getting good information, lamenting the lack of a free press because of the government’s stretching its “tentacles” deep in every news source. “There are many, many,” he writes, “who pay no attention to the newspapers. Why would they?”

But he puts a human face on these generalizations. He tells the story of a man who wouldn’t pay into a Nazi-run community fund because he was caring for the wife and children of a man in a concentration camp. This man lost his job and was also sent to a concentration camp. He expresses disgust at the signs everywhere that say “No Jews!” He writes about the courage some people display in not saying “Heil Hitler,” and the crushing blow it is to the conscience of those who do say it because they have children to feed and fear retribution. “It’s all crazy, isn’t it?” he writes. “But it’s real.”

He realizes he can’t ignore this suffering, even as he reflects on returning to the relatively safe, comfortable suburbs of Philadelphia and to his position at Haverford College. God hadn’t just shown himself to Kelly in a solitary moment of mystical experience, for as he says, “The suffering of the world is a part, too, of the life of God, and so maybe, after all, it is a revelation,” a revelation he knew couldn’t leave him unchanged.

This letter describes the context in which he gave the Cary Lecture. He believed these German Friends needed to hear both the message of the possibility of a vibrant inner life, and also how this inner life invites them into a sacrificial bearing of the burdens of their neighbors and a continued search for joy, the divine glory shimmering in the midst of sorrow.

And now we must say—it sounds blasphemous, but mystics are repeatedly charged with blasphemy—now we must say it is given to us to see the world’s suffering, throughout, and bear it, God-like, upon our shoulders, and suffer with all things and all men, and rejoice with all things and all men, and we see the hills clap their hands for joy, and we clap our hands with them.

A decade ago when I read passages like this in A Testament of Devotion, the admonitions seemed tame, tinged with poetic excess. When I read this today, knowing the context of its writing, I see it differently: it’s a summons to a vocation, the vocation of seeing and acting as one in the world settled in God, open both to the deepest pain and the hidden beauty in the midst of suffering—a call to service and to faith.

The very day I was reading this lecture, holding the 80-year-old, yellowing pages in my hands, students at Haverford College were walking out of their classes in solidarity with their classmates who have lived most of their lives in this country, though illegally, to protest President Donald Trump’s proposed immigration policies. Similar walkouts were occurring on campuses across the country. That same week, Haverford students were in downtown Philadelphia protesting the police brutality they expect to continue under a Trump “law-and-order” administration.

Kelly’s lecture and letter resonate with these current events, not because of parallels between Nazi Germany and the victory of Trump—some have tried to make them, but that’s not my point. Rather, it is the suffering caused by fear (the fear immigrants, African Americans, Muslims, and refugees feel) that Kelly’s spirituality of a dual beyond—the Eternal Beyond, and the beyond within of suffering and joy—might prove able to guide us through, whenever such fear occurs. Just as Kelly’s presence and message were what the German Quakers needed to hear in their time of “increasing anxiety and hopelessness,” so too might the same message be needed in ours.

But this wisdom is useless if it’s not made concrete. There is no “suffering with all” in general, only concrete commitments to this or that person, this or that situation. Kelly knows this, and his most important point in the lecture is the exploration of the load-bearing wall of Quaker spirituality: the concern. A concern names the way a “cosmic suffering” and a “cosmic burden-bearing” become particular in actual existence. A concern names a “particularization”—one of Kelly’s favorite words—of God’s own care for a suffering world in the concrete reality of the life of this person, of this community. It is a “narrowing of the Eternal Imperative to a smaller group of tasks, which become uniquely ours.”

The Quakers in Germany can’t bear the burdens of all of Germany. But, when sensitized to the Spirit, they could discern how God’s care for the world could be made concrete, particular in their life together: in this caring for a neighbor, in this act of resistance, in this fleeting sharing in joy.

While he was reminding those German Quakers of something at the heart of their spirituality, he offered the rest of us a way out of the sense of being overwhelmed when we view the world’s suffering as a whole. “Again and again Friends have found springing up a deep-rooted conviction of responsibility for some specific world-situation.” For Kelly, mysticism included ineffable, inner experience, but also included a sense of the Eternal’s own turning in love toward the world, made concrete in particular lives and communities.

Ileft Haverford with these thoughts distilled into one word as I made my way back to my own community of Pittsburgh, a word that I knew, but Kelly gave to me anew: “discernment.” This is the word I want to carry, to offer to my church, the seminary where I teach, to all those who wonder how to live in the midst of suffering and fear—with the occasional upshot of joy. Discernment. How will God make concrete, particular, in my life, in my church community’s life, God’s own concern for the marginalized, displaced, and discriminated against? How will the mystical become flesh-and-blood in life’s rough-and-tumble, here and now, as it so longs to do?

community

Divine Life

German Friends

German Quakers

God

Haverford College

home

Nazi Germany

person

Philadelphia

Features

Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

L. Roger Owens

L. Roger Owens teaches spirituality and ministry at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary and is the author of What We Need Is Here: Practicing the Heart of Christian Spirituality.