Women and nature: Towards an ecosocialist feminism

It was hot outside that day. In the remote area of KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa a young man watched as five men approached him on the porch. “Could we have a drink?” one of them asked. As they finished the water they asked if they could go inside and thank the woman that lived there. The young man led them in the front door. Moments later shots rang out as the men gunned down the young man’s grandmother an environmental organizer, Fikile Ntshangase, and raced out.

The death of Ntshangase removed a thorn in the side of the Tendele Coal mining company. They had been pressing for over a decade to get the small number of remaining families to vacate their land so their mining operation could expand. Like Berta Cárceres before her, the resistance of Ntshangase and her community is part of a long history of people defending nature as part of defending themselves, their history, their culture, and their future. The role of women like Ntshangase and countless others in defense of nature and with it, life, illustrates the connection between the exploitation of women and the exploitation of nature.

The rise of ecofeminism

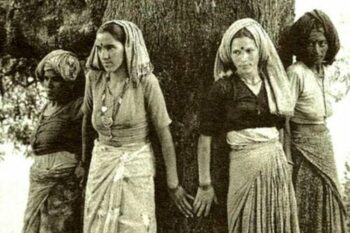

Wherever the forces of destruction attempt to cut down trees, pollute our air and water, and rip away the earth for minerals, women have been leading the resistance. In the cities and communities, women have fought for clean water, air, and land for their families to flourish. From the very first “tree huggers” in the Chipko Movement in India and the Comitato dei danneggiati (Injured Persons’ Committee) protesting pollution in Fascist Italy(1) to the peasants in La Via Campesina, the people of Appalachia fighting mountaintop removal and indigenous defenders of the Amazon, women have been and are today leading communities in struggle against capitalist destruction of our environment.

The rise of second-wave feminism alongside environmental movements in the 1970s led to the emergence of ‘ecofeminist’ politics which saw “a connection between the exploitation and degradation of the natural world and the subordination and oppression of women”.(2) The term ‘ecofeminism’ was coined by the French feminist Françoise d’Eaubonne in her book Le Féminisme ou la Mort (Feminism or Death) published in 1974. One of the first ecofeminist movements is the Green Belt Movement – aimed at preventing desertification by planting trees – in Kenya started by Wangari Maathai in 1977.

Of course, many men are also fierce campaigners against capitalist destruction, organising mass movements to defend the forests and land, like Chico Mendes in the Amazon and Ken Saro-Wiwa in the Niger Delta, who were both tragically murdered for their activism. However, the most well-known environmental activists today are undoubtedly women: Vanessa Nakate and Greta Thunberg, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Naomi Klein, and Vandana Shiva. Even here in Ireland, Maura Harrington helped to lead the Shell to Sea campaign and today the most well known radical environmental activist is arguably Saoirse McHugh.

That both women and nature are dominated and exploited is undeniably true. The question for ecofeminists and ecosocialists is why and what can be done about it?

That both women and nature are dominated and exploited is undeniably true. The question for ecofeminists and ecosocialists is why and what can be done about it?

Ecofeminism, patriarchy & capitalism

For some ecofeminists, women’s affinity to nature comes from ‘their physiological functions (birthing, menstrual cycles) or some deep element of their personalities (life-oriented, nourishing/caring values)’.(3) In this way they “understand” nature, whereas men do not and cannot. Women have a spiritual connection to “Mother” earth. These ecofeminists locate the exploitation and oppression of women and nature in patriarchy, where men control, plunder, rape, and destroy both. Climate change is literally a ‘man-made problem that requires a feminist solution’. The feminist solution, in this case, is more women’s voices, more women in positions of power, and more women at the table discussing their experiences and their ideas on what to do about environmental problems.

Undeniably society is patriarchal (see box). We know it from the statistics and we women know it from the million and one experiences we’ve had that reinforce the idea that men are better, stronger, smarter, and overall more capable.

Undeniably society is patriarchal (see box). We know it from the statistics and we women know it from the million and one experiences we’ve had that reinforce the idea that men are better, stronger, smarter, and overall more capable.

Patriarchal ideas, norms, and behaviours have devastating impacts today on women. Not only from the discrimination, abuse, and violence they face from men as well as the state and state-supported institutions. The highly gendered division of labour in society means women are not only working outside the home to ensure their families have all they need to live, they are also putting in on average three times more hours than men at home. In Ireland, women labour in the home an extra 11 hours a week compared to men. This impacts the kinds of jobs they can take, which affects salary and wages, working conditions, and whether they are free to fully develop their interest and talents.

Women are also at the frontlines of environmental destruction, toxic pollution, as well as climate and ecological breakdown. In Flint, Michigan it was the women in the community who raised their voices when the effects of lead poisoning became clear, and who today, six years on, are still fighting for clean water. As subsistence farmers, producing half the food globally, and in the global South, planting and harvesting as much as 80% of the food, women are forced to reckon with desertification, lack of nutritious food, access to clean water, and destruction of nature in general more than men. In a natural disaster, women are also 14 times more likely to die.

The experiences of these women, who make up the majority of the poorest people on the planet, who have and will be more impacted by the pandemic and its aftermath, should be brought to the centre of discussions about solving climate change and ecological breakdown. Not only because they are most affected, but also because they have unique knowledge and skills that will be key to planning how we can establish a more harmonious interaction between society and nature. Vandana Shiva explains that,

In most cultures women have been the custodians of biodiversity. They produce, reproduce, consume and conserve biodiversity in agriculture. However, in common with all other aspects of women’s work and knowledge, their role in the development and conservation of biodiversity has been rendered as non-work and non-knowledge.(4)

The involvement of women in farmer and peasant organisations expanded the struggle for food sovereignty to include combating gender-based violence and equality for women. The women within La Via Campesina for example ‘defend their rights as women within organisations and society in general…and struggle as peasant women together with their colleagues against the neoliberal model of agriculture’. They help organisations understand the many obstacles preventing women from joining and contributing to movements, in particular ‘the division of labor by gender [which] means that rural women have less access to the most precious resource, time…’

The involvement of women in farmer and peasant organisations expanded the struggle for food sovereignty to include combating gender-based violence and equality for women. The women within La Via Campesina for example ‘defend their rights as women within organisations and society in general…and struggle as peasant women together with their colleagues against the neoliberal model of agriculture’. They help organisations understand the many obstacles preventing women from joining and contributing to movements, in particular ‘the division of labor by gender [which] means that rural women have less access to the most precious resource, time…’

Central to ecofeminism is a rejection of human domination and control over nature in favour of a recognition of ‘…the centrality of human embeddedness in the natural world’.(5) As John Bellamy Foster(6) and other metabolic rift theorists have contended, this is also a central point in Marx’s critique of capitalism. Marx wrote that “[human beings] live from nature…nature is [our] body, we must maintain a continuing dialogue with it if we are not to die. To say that [our] physical and mental life is linked to nature simply means that nature is linked to itself, for [we] are a part of nature.” Unless we struggle for a complete transformation of our society-nature interaction, where production is organised in an ecologically balanced way, the rift between nature and humanity will worsen with devastating consequences for human health, environmental destruction, climate disruption, and irretrievable biodiversity loss.

Capitalism & Patriarchy

Capitalism emerged from a patriarchal feudal society in which male private property inheritance demanded women’s bodies and lives were subordinated to the needs of the family. All kinds of sexist ideas supported women’s supposed inferiority to men, though the forms of oppression women experienced was of course uneven across class and racial lines. Peasant women certainly weren’t forced to learn multiple languages and the basics of etiquette to attract a husband. They worked in the fields and in the home. But they were nonetheless affected by the ideas and culture that emanated from the top of society because as Marx explains,

the ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas… The ruling ideas are nothing more than the ideal expression of the dominant material relationships, the dominant material relationships grasped as ideas…

Patriarchal norms and behaviors, and crucially the laws that enshrined men’s right to own property (including the women of their family), meant that men would become the first capitalists, not women. While rich women were confined to stuffy drawing rooms, crocheting and waiting for the day they would marry and ensure property inheritance continued along the male line, working class women and peasant women, who had no property, laboured as mothers, carers, and domestic servants, regardless of how much they had to work outside the home to survive. Today this continuation of social reproductive labour by women means that even though in many countries they’ve gained political and civil rights–through persistent struggle by countless women as well as LGBTQ+ people and men–the ability of working class and poor women to exercise these rights continues to be restricted. It is hampered by both capitalism’s dependence on the free labour they perform in the home, the undervalued care work and often precarious, part-time work they do in the formal economy, and the sexist ideas that persist and ensure the gendered division of labour is reproduced year after year, generation after generation.

Ecosocialist feminism

While ecofeminists rightly point out the subordination and domination of women and nature as having a common cause, Marxist ecofeminists (or what I would call ecosocialist feminists) disagree that women’s connection to nature is rooted in their reproductive biology. The essentialism of some strands of ecofeminism leads us down a path of biological determinism that so much of second-wave feminism was fighting to destroy, and we are still struggling against.(7) We also need to reckon with the revolution in the gender/sex binary demanded by trans, intersex, and gender non-conforming people who do not and will not fit into the simple male/female categories and all the cultural baggage that goes with it.

While ecofeminists rightly point out the subordination and domination of women and nature as having a common cause, Marxist ecofeminists (or what I would call ecosocialist feminists) disagree that women’s connection to nature is rooted in their reproductive biology. The essentialism of some strands of ecofeminism leads us down a path of biological determinism that so much of second-wave feminism was fighting to destroy, and we are still struggling against.(7) We also need to reckon with the revolution in the gender/sex binary demanded by trans, intersex, and gender non-conforming people who do not and will not fit into the simple male/female categories and all the cultural baggage that goes with it.

While we recognise the unique knowledge women have in care work, for families and for nature, we don’t accept that it’s inherently female or feminine, as some ecofeminism suggests. Cleaning the house, cooking meals, raising children, farming to feed your family, or gathering the daily water is not “women’s work”, but rather the needs of society forced onto their backs. “Saving the planet” is not inherently women’s work or responsibility either. We want to end the gender division in and outside the home and we demand this work is organised amongst the wider community, for example through free public childcare, community laundromats and canteens. This would have the effect of freeing women from this work now, but would also opens the door to a society in which the community is responsible for organising social reproductive work and sexist ideas about “women’s” vs. “men’s work” can begin to wither away. Women will then be free to choose what work they want to engage in, including the farming, environmental/ecological work so many already perform, enriching all of society by their contributions.

In contrast to “essentialist” ecofeminism, ecosocialist feminism sees women’s “connection” to nature and our environment as socially constructed and reinforced for material reasons. “[W]omen are not ‘one’ with nature…[we’ve] been ‘thrown into an alliance” with it.(8)

Capitalism treats nature and women’s social reproductive labour as ‘free gifts’, completely outside the formal economy (and therefore without value) and yet absolutely central to its ability to generate profits. For example, the value of an old-growth forest is not accounted for when the trees are felled and the wood used to make furniture. Under capitalism, the value of a commodity (whether it’s a shirt or a house) is based on the average amount of labour power used to make it, including the work that went into acquiring the materials, but not the “value” of the raw materials in themselves. It’s the same for domestic labour. Labour in the home – the cooking, cleaning, and shopping – ensures workers are fit and able to labour in the workplace day after day;and the labour required in birthing and caring for children ensures a new generation of workers is prepared to enter the workplace and create wealth for the capitalists. This is all done primarily by women and for free as far as capitalism is concerned. These ‘free gifts’–from nature and women–are ‘expropriated’ by capitalism. They are taken and consumed in the process of capital accumulation without compensation, cheapening the cost of production and externalizing the real costs onto the rest of society.(9)

For Marxist ecofeminists, the domination of men over women in society and nature at large is therefore not a result of patriarchal ideas alone. Their continuation and utilisation by capitalism maintains divisions between women and men (alongside black/white, straight/LGBTQ, cis/non-binary) workers and poor people to ensure profits continue and their rotten class system endures.

For Marxist ecofeminists, the domination of men over women in society and nature at large is therefore not a result of patriarchal ideas alone. Their continuation and utilisation by capitalism maintains divisions between women and men (alongside black/white, straight/LGBTQ, cis/non-binary) workers and poor people to ensure profits continue and their rotten class system endures.

Most importantly, ecosocialist feminists underscore the crucial difference between working class or peasant women and women who make it to the top echelons of power. Ecofeminism can sometimes “over-romanticiz[e] women and women’s history…” and “[assert] a ‘totalizing’ image of a universalized ‘woman’,… ignoring women’s differences”.(10) While all women experience sexism, the needs and demands of “women”, even working-class and peasant women, are not uniform. Not all working-class women were forced into the role of housewife. As black revolutionary socialist Claudia Jones explained in her essay ‘An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman!’, capitalism’s structural racism meant that black women in the 1940s were often the main breadwinner in the family and had to work long hours, usually cleaning or childminding for white families, before they came home to labour for their own.(11)

We also need to keep in mind that the call for more women’s voices is all too easily met within capitalism with the Josepha Madigans, Angela Merkels and Ursula Von Der Leyens of the world. The new Biden administration in the U.S. is the most recent case in point with the first black and Asian vice president and the first indigenous woman to lead the Department of Interior.

The rise of the new women’s movement alongside a growing climate justice movement gives impetus to ecofeminist ideas, which is overall positive (despite the essentialist arguments, which must be strongly countered). Yet, as long as private property rights are upheld for corporations to do basically whatever they want to the forests, land, and water with impunity and as long as states act in their interests against ours, whether it’s by the hands of men or women, nature will continue to be destroyed, the climate disrupted, and women will disproportionately suffer (with poor, black and brown and marginalised women suffering the worst). We must go much further and demand an ecofeminism that is unflinchingly anti-capitalist and socialist and move towards an ecosocialist feminism that sees our labour as the beginning of the way out. Under patriarchal and racial(13) capitalism, working women and peasants labour in and outside the home. This dual role gives them an insight into the unsustainability and destructive character of capitalism. It’s why so many movements for radical change are led by women, despite the extra barriers in our way. But it is in our labour in the workplaces and where we produce for capital that we have the most power to fight and win.

Like fuel to the engine, profit is what powers capitalism, and all profit comes from our labour in the workplace. Whether we’re cleaning the floors, staffing the till, or operating machinery in a production line, our labour is what keeps the capitalist system going. If we decide to take collective action, to slow down our work or even go on strike, for an hour, a day or indefinitely, it would bring businesses, cities, and even whole countries to a grinding halt. This means workers, which comprise the exploited and oppressed majority, actually have tremendous potential power when we are organised.

Women workers alongside the men in their workplaces have used their power to fight back against the sexism they experience–as McDonald’s workers did–and to go after big oil–as teachers in West Virginia did. When the INMO went on strike in 2019 they made clear that their demands for pay and retention directly impacted the inadequate healthcare we all receive, and while they didn’t win everything they demanded, they won more than the government was originally offering. We need to build on these examples and countless others from history, strengthen our ties in workplaces as well as the community and get organised to challenge patriarchal capitalism wherever it attacks life, in society and our environment.

Notes:

- Ledda, Rachel, 2018. Women’s presence in contemporary Italy’s environmental movements, with a case study on the Mamme No Inceneritore committee, Genre et environnement.

- Mellor, M. (1996) ‘The Politics of Women and Nature: Affinity, Contingency or Material Relation?’, Journal of Political Ideologies, vol. 1, no. 2.

- Ibid

- Mies, M. and Shiva, V., 2014, Women’s Indigenous Knowledge and Biodiversity Conservation” from Ecofeminism, Zed Books, New York.

- Mellor, M. (1996) ‘The Politics of Women and Nature: Affinity, Contingency or Material Relation?’, Journal of Political Ideologies, vol. 1, no. 2.

- See Marx’s Ecology (2000) by John Bellamy Foster and Karl Marx’s Ecosocialism (2018) by Kohei Saito.

- Marx, Karl, 1845-6, The German Ideology, Part I: Feuerbach. Opposition of the Materialist and Idealist Outlook B. The Illusion of the Epoch.

- That is, reproductive ability should determine (and in many cases, limit) your role in the home and in the workplace to those deemed “women’s” work – childminding, cooking, cleaning, teaching, nursing, and so on.

- Mellor, M. (1996) ‘The Politics of Women and Nature: Affinity, Contingency or Material Relation?’, Journal of Political Ideologies, vol. 1, no. 2.

- See monthlyreview.org

- Mellor, M. (1996) ‘The Politics of Women and Nature: Affinity, Contingency or Material Relation?’, Journal of Political Ideologies, vol. 1, no. 2.

- See Spear, Jess, ‘Lesser-spotted comrades: Claudia Jones’, Rupture, Autumn 2020.

- ‘Racial’ capitalism denotes the history of capitalism’s development was a history of brutal chattel slavery, the genocide of indigenous peoples, and immense destruction of the natural world. “Capital” Marx wrote in Capital Volume 1, “[came] dripping from head to foot, from every pore, with blood and dirt”.