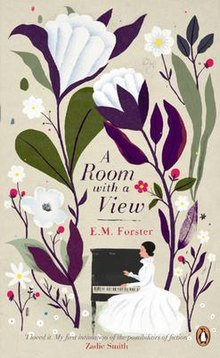

A Room with a View

Cover of Penguin Essentials edition (2011) | |

| Author | E. M. Forster |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Novel |

| Publisher | Edward Arnold |

Publication date | 1908 |

| Media type | Print (hardcover) |

| Pages | 321 |

A Room with a View is a 1908 novel by English writer E. M. Forster, about a young woman in the restrained culture of Edwardian era England. Set in Italy and England, the story is both a romance and a humorous critique of English society at the beginning of the 20th century. Merchant Ivory produced an award-winning film adaptation in 1985.

The Modern Library ranked A Room with a View 79th on its list of the 100 best English-language novels of the 20th century (1998).

Plot summary[edit]

Part one[edit]

The novel is set in the early 1900s as upper-middle-class English women are beginning to lead more independent, adventurous lives. In the first part, Miss Lucy Honeychurch is touring Italy with her overly-fussy spinster cousin and chaperone, Miss Charlotte Bartlett. The novel opens in Florence with the women complaining about their rooms at the Pensione Bertolini. They were promised rooms with a view of the River Arno but instead have ones overlooking a drab courtyard. Another guest, Mr Emerson, interrupts their "peevish wrangling" by spontaneously offering to swap rooms. He and his son, George, both have rooms with views of the Arno, and he argues, "Women like looking at a view; men don’t." Charlotte rejects the offer, partly because she looks down on the Emersons' unconventional behaviour and because she fears it would place them under an "unseemly obligation". However, another guest, Mr Beebe, an Anglican clergyman, persuades Charlotte to accept the offer; Charlotte suggests that the Emersons are socialists.

The following day, Lucy spends a "long morning" in the Basilica of Santa Croce, accompanied by Miss Eleanor Lavish, a novelist who promises to lead her on an adventure. Lavish confiscates Lucy's Baedeker guidebook, proclaiming she will show Lucy the "true Italy". On the way to Santa Croce, the two take a wrong turn and get lost. After drifting for hours through various streets and piazzas, they eventually make it to the square in front of the church, only for Lavish (who still has Lucy's Baedeker) to abandon the younger woman to pursue an old acquaintance.[1]

Inside the church, Lucy runs into the Emersons. Although the other visitors find Mr. Emerson's behavior somewhat unrefined, Lucy discovers she likes them both; she repeatedly encounters them in Florence. While touring Piazza della Signoria, Lucy and George Emerson separately witness a murder. Overcome by its gruesomeness, Lucy faints and is aided by George. Recovered, she asks him to retrieve the photographs she dropped near the murder scene. George finds them, but as they are covered in blood, he throws them into the river before telling Lucy; Lucy observes how boyish George is. As they stop by the River Arno before returning to the pensione, they engage in a personal conversation.

Lucy decides to avoid George, partly because she is confused by her feelings, and also to placate Charlotte who grows wary of the eccentric Emersons. She overheard Mr Eager, a clergyman, saying that Mr Emerson, "murdered his wife in the sight of God".

Later in the week, Mr Beebe, Mr Eager, the Emersons, Miss Lavish, Charlotte, and Lucy go on a day trip to Fiesole, a scenic area above Florence, driven in two carriages by Italian drivers. One driver is permitted to have a pretty girl he claims is his sister sit next to him on the box seat. When he kisses her, Mr Eager promptly orders her to leave. In the other carriage, Mr Emerson remarks how it is defeat rather than victory to part two people in love.

On a hillside, Lucy abandons Miss Lavish and Miss Bartlett to their gossip and goes searching for Mr Beebe. Misunderstanding Lucy's awkward Italian, the driver leads her to where George is admiring the view. Overcome by Lucy's beauty amongst a field of violets, he takes her in his arms and kisses her. However, they are interrupted by Charlotte, who is shocked and upset but mostly is ruffled by her own failure as a chaperone. Lucy promises Charlotte that she will say nothing to her mother about the "insult" George has paid her. The two women leave for Rome the next day before Lucy can say goodbye to George.

Part two[edit]

In Rome, Lucy spends time with Cecil Vyse, whom she knew in England. Cecil twice proposes to Lucy in Italy; she rejects him both times. As Part Two begins, Lucy has returned to Surrey, England, to her family home, Windy Corner. Cecil proposes yet again and this time she accepts. Cecil is a sophisticated London aesthete whose rank and class make him a desirable match, despite his despising country society; he is a rather comic figure who is snobbish and gives himself pretentious airs.

The vicar, Mr Beebe, announces that a local villa has been leased; the new tenants are the Emersons, who, after a chance meeting with Cecil in London, learned about the villa being available. Cecil enticed them to come to the village as a comeuppance to the villa's landlord, Sir Harry Otway, whom Cecil (who believes himself to be very democratic) thinks is a snob. Lucy is angry with Cecil, as she had tentatively arranged for the elderly Misses Alan, who had also been guests at the Pensione Bertolini, to rent the villa.

Fate takes an ironic turn as Mr Beebe introduces Lucy's brother, Freddy, to the Emersons. Freddy invites George for "a bathe" in a nearby pond in the woods. Freddy, George, and Mr Beebe go there. Freddy and George undress and jump in, eventually convincing Mr. Beebe to join them. The men enjoy themselves, frolicking and splashing in and out of the pond and running through the bushes until Lucy, her mother, and Cecil come upon them, having taken a short-cut through the woods during their walk.

Freddy later invites George to play tennis at Windy Corner. Although Lucy is initially mortified by facing both George and Cecil, she resolves to be gracious. Cecil annoys everyone by pacing around and reading aloud from a light romance novel that contains a scene suspiciously reminiscent of George's kissing Lucy in Fiesole. George catches Lucy alone in the garden and kisses her again. Lucy realises that the novel was written by Miss Lavish (the writer-acquaintance from Florence) and that Charlotte must thus have told her about the kiss.

Furious with Charlotte for betraying her secret, Lucy forces her cousin to watch as she orders George to leave Windy Corner and never return. George argues that Cecil only sees Lucy as an "object for the shelf" and will never love her enough to grant her independence, while George loves her for who she is. Lucy is moved but remains firm. Later that evening, after Cecil again rudely declines to play tennis, Lucy sees Cecil for what he truly is and ends their engagement. She decides to flee to Greece with the two Misses Alan.

Meanwhile, George, unable to bear being around Lucy, is moving his father back to London, unaware Lucy has broken off her engagement. Shortly before Lucy's departure, she accidentally encounters Mr Emerson at Mr Beebe's house. He is unaware that Lucy is no longer engaged, and Lucy is unable to lie to him. With open, honest talk, Mr Emerson, strips away her defences, forcing Lucy to admit she has been in love with George all along. He also mentions how his wife had "gone under"—lost the will to live—because she feared that George's contracting typhoid at the age of 12 was a punishment for his not being baptized. Her fear was the result of a visit by the stern clergyman Mr Eager, and the incident explains Eager's later claim that Mr Emerson had "murdered his wife in the sight of God".

The novel ends in Florence, where George and Lucy have eloped without Mrs Honeychurch's consent. However, Lucy has learned that Charlotte knew that Mr. Emerson was at Mr. Beebe's that fateful day and had not discouraged or prevented her from going in and encountering him. Although Lucy "had alienated Windy Corner, perhaps forever" (although the appendix implies a reconciliation with her family), the story ends with the promise of lifelong love for both her and George.

Appendix[edit]

In some editions, an appendix to the novel is given entitled "A View without a Room", written by Forster in 1958 as to what occurred between Lucy and George after the events of the novel. It is Forster's afterthought of the novel, and he quite clearly states that, "I cannot think where George and Lucy live." They were quite comfortable up until the end of the First World War, with Charlotte Bartlett leaving them all her money in her will, but the war ruined their happiness according to Forster. George became a conscientious objector and lost his government job. He was given non-combatant duties to avoid prison. This left Mrs Honeychurch deeply upset with her son-in-law. Mr Emerson died during the war, shortly after having a confrontation with police over Lucy's playing the music of a German composer, Beethoven, on the piano. Eventually the couple had three children, two girls and a boy, and moved to Carshalton from Highgate to find a home. Despite their wanting to move into Windy Corner after Mrs Honeychurch's death, Freddy sold the house to support his family, as he was "an unsuccessful but prolific doctor".

After the outbreak of the Second World War, George immediately enlisted as he saw the need to stop Hitler and the Nazi regime. He was unfaithful to Lucy during his time at war. Lucy was left homeless after her flat in Watford was bombed and the same happened to her married daughter in Nuneaton. George rose to the rank of corporal but was taken prisoner by the Italians in Africa. Once the fascist government in Italy fell, George returned to Florence. Finding it "in a mess", he was unable to find the Pensione Bertolini, stating, "the View was still there," and that "the room must be there, too, but could not be found." Forster ends by stating that George and Lucy await the Third World War, but with no word on where they live, for even he does not know.

He adds that Cecil served in "Information or whatever the withholding of information was then entitled" during the war, and was able to trick an Alexandria hostess into playing Beethoven's Moonlight Sonata by claiming he was Belgian, not German.

Allusions to other works[edit]

- Mr Beebe recalls his first encounter with Lucy was hearing her play the first of the two movements of Beethoven's final piano sonata, Opus 111, at a talent show in Tunbridge Wells.

- While visiting the Emersons Mr Beebe contemplates the numerous books strewn around.

- "I fancy they know how to read – a rare accomplishment. What have they got? Byron. Exactly. A Shropshire Lad. Never heard of it. The Way of All Flesh. Never heard of it. Gibbon. Hullo! Dear George reads German. Um – um — Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, and so we go on. Well, I suppose your generation knows its own business, Honeychurch." [1]

- Towards the beginning of Part Two, Cecil quotes a few unidentified stanzas ("Come down, O maid, from yonder mountain height", etc.). They are from Tennyson's narrative poem "The Princess".

- In the Emersons' home, the wardrobe has "Mistrust all enterprises that require new clothes" (a quote from Henry David Thoreau's Walden) painted upon it.

- In chapter five, after bemoaning the fact that people do not appreciate landscape paintings any more, Mr Eager misquotes William Wordsworth's poem title, "The World Is Too Much With Us", saying "The world is too much for us."

- Cecil announces his engagement to Lucy with the words: "I promessi sposi" ("the betrothed") – a reference either to the 1856 Ponchielli opera of that name or the Manzoni novel on which it is based.

- When George is lying on the grass in Part Two, Lucy asks him about the view, and he replies, "My father says the only perfect view is the sky over our heads", prompting Cecil to make a throwaway comment about the works of Dante.

- Late in the novel, Lucy sings a song from Sir Walter Scott's The Bride of Lammermoor, finishing with the lines 'Vacant heart, and hand, and eye,-/Easy live and quiet die'. Forster also incorporated Donizetti's operatic adaptation of Scott's novel, Lucia di Lammermoor, into the concert scene of his first published novel, Where Angels Fear to Tread. Like A Room with a View, The Bride of Lammermoor is centred on a talented but restrained young woman encouraged into an engagement not of her choosing.

Writing[edit]

A Room with a View had a lengthy gestation. By late 1902 Forster was working on a novel set in Italy which he called the 'Lucy novel'. In 1903 and 1904 he pushed it aside to work on other projects. He was still revising it in 1908.[2]

Stage, film, radio, and television adaptations[edit]

The novel was first adapted for the theatre by Richard Cottrell with Lance Severling for the Prospect Theatre Company, and staged at the Albery Theatre on 27 November 1975 by directors Toby Robertson and Timothy West.

Merchant Ivory produced an award-winning film adaptation in 1985 directed by James Ivory and starring Maggie Smith as "Charlotte Bartlett", Helena Bonham Carter as "Lucy Honeychurch", Judi Dench as "Eleanor Lavish", Denholm Elliott as "Mr Emerson", Julian Sands as "George Emerson", Daniel Day-Lewis as "Cecil Vyse" and Simon Callow as "The Reverend Mr Beebe".

BBC Radio 4 produced a four-part radio adaptation written by David Wade and directed by Glyn Dearman (released commercially as part of the BBC Radio Collection) in 1995 starring Sheila Hancock as "Charlotte Bartlett", Cathy Sara as "Lucy Honeychurch", John Moffat as "Mr Emerson", Gary Cady as "George Emerson" and Stephen Moore as "The Reverend Mr Beebe". The production was rebroadcast on BBC7 in June 2007, April 2008, June 2009 and March 2010 and on BBC Radio 4 Extra in August 2012 and March 2017.

In 2006, Andrew Davies announced that he was to adapt A Room with a View for ITV.[3] This was first shown on ITV1 on 4 November 2007. It starred father and son actors Timothy and Rafe Spall as Mr Emerson and George, together with Elaine Cassidy (Lucy Honeychurch), Sophie Thompson (Charlotte Bartlett), Laurence Fox (Cecil Vyse), Sinéad Cusack (Miss Lavish), Timothy West (Mr Eager) and Mark Williams (Reverend Beebe). This adaptation was broadcast in the US on many PBS stations on Sunday 13 April 2008.

A musical version of the novel, directed by Scott Schwartz, opened at San Diego's Old Globe Theatre[4] in previews on March 2, 2012 with opening night March 10, and ran through April 15. Conceived by Marc Acito, the production featured music and lyrics by Jeffrey Stock and additional lyrics by Acito. The cast included Karen Ziemba (Charlotte Bartlett), Ephie Aardema (Lucy Honeychurch), Kyle Harris (George Emerson) and Will Reynolds (Cecil Vyse).

A reworked version of the musical opened at Seattle's 5th Avenue Theatre[5] on April 15, 2014, following two weeks of previews, and ran through May 11. Directed by David Armstrong (director), the show's cast featured Louis Hobson (George Emerson), Laura Griffith (Lucy Honeychurch), Allen Fitzpatrick (Mr. Emerson), Patti Cohenour (Charlotte Bartlett), and Richard Gray (Reverend Beebe).

L.A. Theatre Works recorded an audio adaptation of the novel at UCLA's James Bridges Theater in March 2019.[6] The production featured Julian Sands as Mr. Emerson Sr., Eugene Simon as George Emerson, and Eleanor Tomlinson as Lucy Honeychurch. It is available for streaming online in two parts, Part 1 and Part 2.

In 2020, Kevin Kwan released his novel Sex and Vanity, a contemporary adaptation, in which the characters are well-connected aristocrats, and some are Crazy Rich Asians.

In popular culture[edit]

- Noël Coward composed the 1928 hit song called "A Room with a View", whose title he acknowledged as coming from Forster's novel.

- A scene from the film adaptation is viewed by the main characters of the U.S. television show Gilmore Girls in the 2004 episode "A Messenger, Nothing More". Rory tells Lorelai that she wants to show her home movies from her trip to Europe with her grandmother. A clip of Maggie Smith lamenting their lack of views is shown.

- The first verse of Rage Against the Machine's 1992 song "Know Your Enemy" features the line "As we move into '92/Still in a room without a view".

- The title of The Divine Comedy's 2005 album Victory for the Comic Muse is taken from a line in the book. The track "Death of a Supernaturalist" from their album Liberation opens with George Emerson's line, "My father says there is only one perfect view, and that's the view of the sky over our heads", followed by Cecil's, "I expect your father has been reading Dante".

- In the 2007 episode "Branch Wars" of the U.S. television show The Office, the Finer Things Club is seen reading and discussing the book over an English tea party.

- The film adaptation is discussed by the main characters of the 2011 British romantic drama Weekend.

References[edit]

- ^ See the Dover Thrift Edition [New York, 1995], pp. 13–16.

- ^ Moffat, Wendy E. M. Forster: A New Life, London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2010

- ^ BBC News (2006): Davies to adapt Room with a View

- ^ Playbill.com (2012)

- ^ Playbill.com (2014)

- ^ L.A. Theatre Works Catalog

External links[edit]

- A Room with a View at Standard Ebooks

- A Room with a View at Project Gutenberg

A Room with a View public domain audiobook at LibriVox

A Room with a View public domain audiobook at LibriVox- Plot summary and links

- A Room with a View at the British Library