Quotation

"You are walking on the earth as in a dream. Our world is a dream within a dream; you must realize that to find God is the only goal, the only purpose, for which you are here. For Him alone you exist. Him you must find." – from the book The Divine Romance

Paramahansa Yogananda (born Mukunda Lal Ghosh; January 5, 1893 – March 7, 1952) was an Indian Hindu monk, yogi and guru who introduced millions to the teachings of meditation and Kriya Yoga through his organization Self-Realization Fellowship (SRF) / Yogoda Satsanga Society (YSS) of India, and who lived his last 32 years in America. A chief disciple of the Bengali yoga guru Swami Sri Yukteswar Giri, he was sent by his lineage to spread the teachings of yoga to the West, to prove the unity between Eastern and Western religions and to preach a balance between Western material growth and Indian spirituality.[2] His long-standing influence in the American yoga movement, and especially the yoga culture of Los Angeles, led him to be considered by yoga experts as the "Father of Yoga in the West."[3][4]

Yogananda was the first major Indian teacher to settle in America, and the first prominent Indian to be hosted in the White House (by President Calvin Coolidge in 1927);[5] his early acclaim led to him being dubbed "the 20th century's first superstar guru," by the Los Angeles Times.[6] Arriving in Boston in 1920, he embarked on a successful transcontinental speaking tour before settling in Los Angeles in 1925. For the next two and a half decades, he gained local fame as well as expanded his influence worldwide: he created a monastic order and trained disciples, went on teaching-tours, bought properties for his organization in various California locales, and initiated thousands into Kriya Yoga.[4] By 1952, SRF had over 100 centers in both India and the US; today, they have groups in nearly every major American city.[6] His "plain living and high thinking" principles attracted people from all backgrounds among his followers.[4]

He published his book, Autobiography of a Yogi, in 1946, to critical and commercial acclaim; since its first publishing, it has sold over four million copies, with HarperSan Francisco listing it as one of the "100 best spiritual books of the 20th Century".[6][7] Former Apple CEO Steve Jobs had ordered 500 copies of the book for his own memorial, for each guest to be given a copy.[8] The book has been regularly reprinted and is known as "the book that changed the lives of millions."[9][10] A 2014 documentary, Awake: The Life of Yogananda, won multiple awards at film festivals around the world. His continued legacy around the world, remaining a leading figure in Western spirituality to the current day, led authors such as Philip Goldberg to consider him "the best known and most beloved of all Indian spiritual teachers who have come to the West....through the strength of his character and his skillful transmission of perennial wisdom, he showed the way for millions to transcend barriers to the liberation of the soul."[11]

Biography[edit]

Youth and discipleship[edit]

Yogananda was born in Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh, India, to a Hindu Bengali Kayastha family.[12] He was the fourth of the eight children, and second of the four sons, of Bhagabati Charan Ghosh, the Vice President of Bengal-Nagpur Railway, and Gyanprabha Devi. According to his younger brother, Sananda, from his earliest years young Mukunda's awareness and experience of the spiritual was far beyond the ordinary.[12] Since his father was a Vice-President of the Bengal Nagpur Railway, the traveling nature of his job would move his family to several cities during Yogananda's childhood, including Lahore, Bareilly, and Kolkata.[2] According to Autobiography of a Yogi, when he was eleven years old, his mother died, just before the betrothal of his eldest brother Ananta; she left behind for Mukunda a sacred amulet, given to her by a holy man, who told her that Mukunda was to possess it for some years, after which it would vanish into the ether from which it came. Throughout his childhood, his father would fund train-passes for his many sight-seeing trips to distant cities and pilgrimage spots, which he would often take with friends. In his youth he sought out many of India's Hindu sages and saints, including the Soham "Tiger" Swami, Gandha Baba, and Mahendranath Gupta, hoping to find an illumined teacher to guide him in his spiritual quest.[2]

After finishing high school, Yogananda formally left home and joined a Mahamandal Hermitage in Varanasi; however, he soon became dissatisfied with its insistence on organizational work instead of meditation and God-perception. He began praying for guidance; in 1910, his seeking after various teachers mostly ended when, at the age of 17, he met his guru, Swami Sri Yukteswar Giri.[2] At this time, his well-guarded amulet mysteriously vanished, having had served its spiritual purpose. In his autobiography, he describes his first meeting with Sri Yukteswar as a rekindling of a relationship that had lasted for many lifetimes:

"We entered a oneness of silence; words seemed the rankest superfluities. Eloquence flowed in soundless chant from heart of master to disciple. With an antenna of irrefragable insight I sensed that my guru knew God, and would lead me to Him. The obscuration of this life disappeared in a fragile dawn of prenatal memories. Dramatic time! Past, present, and future are its cycling scenes. This was not the first sun to find me at these holy feet!"[2]

He would go on to train under Sri Yukteswar as his disciple for the next ten years (1910–1920), at his hermitages in Serampore and Puri. Later on Sri Yukteswar informed Yogananda that he had been sent to him by the great guru of their lineage, Mahavatar Babaji, for a special world purpose of yoga dissemination.[2]

After passing his Intermediate Examination in Arts from the Scottish Church College, Calcutta, in 1914, he graduated with a degree similar to a current day Bachelor of Arts or B.A. (which at the time was referred to as an A.B.), from Serampore College, the college having two entities, one as a constituent college of the Senate of Serampore College (University) and the other as an affiliated college of the University of Calcutta. This allowed him to spend time at Yukteswar's ashram in Serampore.

In July 1914, several weeks after graduating from college, he took formal vows into the monastic Swami order; Sri Yukteswar allowed him to choose his own name: Swami Yogananda Giri.[2] In 1917, Yogananda founded a school for boys in Dihika, West Bengal, that combined modern educational techniques with yoga training and spiritual ideals. A year later, the school relocated to Ranchi.[2] One of the school's first batch of pupils was his youngest brother, Bishnu Charan Ghosh, who learned yoga asanas there and in turn taught asanas to Bikram Choudhury.[13] This school would later become the Yogoda Satsanga Society of India, the Indian branch of Yogananda's American organization, Self-Realization Fellowship.

Teaching in America[edit]

In 1920, while in meditation one day at his Ranchi school, Yogananda received a vision - faces of a multitude of Americans passed before his mind's eye, intimating to him that he would soon go to America. After giving charge of the school over to its faculty (and eventually to his brother disciple Swami Satyananda), he left for Calcutta; the following day he received an invitation from the American Unitarian Association to serve as India's delegate to an International Congress of Religious Liberals convening that year in Boston.[14] Seeking out his guru's advice, Sri Yukteswar advised him to go; later, while in deep prayer in his room, he received a surprise visit from Mahavatar Babaji, the Great Guru of his lineage, who told him directly that he was the one chosen by the Masters to spread Kriya Yoga to the West. Reassured and uplifted, Yogananda soon afterwards accepted the offer to go to Boston. This account became a standard feature of his lectures.

In August 1920, he left for the United States aboard the ship "The City of Sparta," on a two-month voyage that landed near Boston by late September.[15] He spoke at the International Congress in early October, and was well received; later that year he founded the Self-Realization Fellowship (SRF) to disseminate worldwide his teachings on India's ancient practices and philosophy of Yoga and its tradition of meditation.[16] Yogananda spent the next four years in Boston; in the interim, he lectured and taught on the East Coast[17] and in 1924 embarked on a cross-continental speaking tour.[18] Thousands came to his lectures.[2] During this time he attracted a number of celebrity followers, including soprano Amelita Galli-Curci, tenor Vladimir Rosing and Clara Clemens Gabrilowitsch, the daughter of Mark Twain. In 1925, he established an international center for Self-Realization Fellowship in Los Angeles, California, which became the spiritual and administrative heart of his growing work.[15][19] Yogananda was the first Hindu teacher of yoga to spend a major portion of his life in America. He lived in the United States from 1920 to 1952, interrupted by an extended trip abroad in 1935–1936, and through his disciples he developed various Kriya Yoga centers around the world.

Yogananda was put on a government watch list and kept under surveillance by the FBI and the British authorities, who were concerned about the growing independence movement in India.[20] A confidential file was kept on him from 1926 to 1937 due to concern over his religious and moral practices.[21] Philip Goldberg's biography describes Yogananda as being up against a perfect storm of America's worst defects: media sensationalism, religious bigotry, ethnic stereotyping, paternalism, sexual anxiety, and brazen racism.[22]

In 1928, Yogananda received unfavorable publicity in Miami and the police chief, Leslie Quigg, prohibited Yogananda from holding any further events. Quiggs said it was not due to a personal grudge against the Swami but rather in the interest of public order and Yogananda's own safety. Quigg had received veiled threats against Yogananda.[23] According to Phil Goldberg, it turns out that Miami officials had summoned the British vice consulate to advise them on the matter ... one consulate officer said that the Miami city manager and Chief Quigg 'recognized the fact that the swami was a British subject and apparently an educated man, but unfortunately he was what is considered in this part of the country a coloured man.’ Given the South’s cultural mores, he noted, ‘the swami was in great danger of suffering bodily harm from the populace.’"[22]

Visit to India, 1935–1936[edit]

In 1935, he returned to India via ocean liner, along with two of his western students, to visit his guru Sri Yukteswar Giri and to help establish his Yogoda Satsanga work in India. While enroute, his ship detoured in Europe and the Middle East; he undertook visits to other living western saints like Therese Neumann, the Catholic Stigmatist of Konnersreuth, and places of spiritual significance: Assisi, Italy to honor St. Francis, the Athenian temples of Greece and prison cell of Socrates, the Holy Land of Palestine and the regions of the Ministry of Jesus, and Cairo, Egypt to view the ancient Pyramids.[2][24]

In August 1935, he arrived in India at the port of Mumbai and due to his fame in America, he was met with many photographers and journalists during his short stay at the Taj Mahal Hotel. Upon taking a train eastward and reaching the Howrah Station near Kolkata, he was met with a huge crowd and a ceremonious procession led by his brother, Bishnu Charan Ghosh, and the Maharaja of Kasimbazar. Visiting Serampore, he had an emotional reunion with his guru Sri Yukteswar, which was noted in detail by his western student C. Richard Wright.[2] During his stay in India, he saw his Ranchi boys' school become legally incorporated, and took a touring group to visit various locales: the Taj Mahal in Agra, the Chamundeshwari Temple in Mysore, Allahabad for the Kumbh Mela of January 1936, and Brindaban to visit an exalted disciple of Lahiri Mahasaya, Swami Keshabananda.[2]

He also met with other various people who caught his interest: Mahatma Gandhi, whom he initiated into Kriya Yoga; woman-saint Anandamoyi Ma; Giri Bala, an elderly yogi woman who survived without eating; renowned physicist Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman, and several disciples of Sri Yukteswar's guru Lahiri Mahasaya.[2] While in India, Sri Yukteswar gave Yogananda the monastic title of Paramahansa, meaning "supreme swan" and indicating the highest spiritual attainment, which formally superseded his previous title of "swami."[25] In March 1936, upon Yogananda's return to Calcutta after visiting Brindaban, Sri Yukteswar died (or, in the yogic tradition, attained mahasamadhi)[26] at his hermitage in Puri. After conducting his guru's funeral rites, Yogananda continued to teach, conduct interviews, and meet with friends for several months, before planning to return to the US in mid-1936.

According to his autobiography, in June 1936, after having a vision of Krishna, he had a supernatural encounter with the resurrected Spirit of his guru Sri Yukteswar while in a room at the Regent Hotel in Mumbai. During the experience, in which Yogananda physically grasped and held onto his guru's solid form, Sri Yukteswar explained that he now served as a spiritual guide on a high-astral planet, and expounded truths in deep detail regarding: the astral realm, astral planets and the afterlife; the lifestyles, abilities and varying levels of freedoms of astral beings; the workings of karma; man's various super physical bodies and how he works through them, and other metaphysical topics.[2] With new wisdom and renewed from the encounter, Yogananda and his two western students left India via ocean liner from Mumbai; staying for several weeks in England, they conducted several yoga classes in London and visited historical sites, before leaving for the US in October 1936.

Return to America, 1936[edit]

In late 1936, Yogananda's ship arrived in New York harbor, passing the Statue of Liberty; he and his companions then drove in his Ford car across the continental US back to his Mount Washington, California headquarters. Rejoined with his American disciples, he continued to lecture, write, and establish churches in southern California. He took up residence at the SRF hermitage in Encinitas, California which was a surprise gift from his advanced disciple Rajarsi Janakananda.[27][28] It was at this hermitage that Yogananda wrote his famous Autobiography of a Yogi and other writings. Also, at this time he created an "enduring foundation for the spiritual and humanitarian work of Self‑Realization Fellowship/Yogoda Satsanga Society of India."[29]

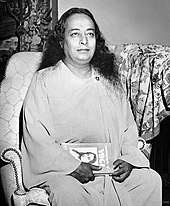

Yogananda with his autobiography, 1950 In 1946, Yogananda took advantage of a change in immigration laws and applied for citizenship. His application was approved in 1949, and he became a naturalized U.S. citizen.[22]

The last four years of his life were spent primarily in seclusion with some of his inner circle of disciples at his desert retreat in Twentynine Palms, California to finish his writings and to finish revising books, articles and lessons written previously over the years.[30] During this period he gave few interviews and public lectures. He told his close disciples, "I can do much more now to reach others with my pen."[31]

In the days leading up to his death, Yogananda began hinting to his disciples that it was time for him to leave the world.[32]

On March 7, 1952, he attended a dinner for the visiting Indian Ambassador to the U.S., Binay Ranjan Sen, and his wife at the Biltmore Hotel in Los Angeles.[33] At the conclusion of the banquet, Yogananda spoke of India and America, their contributions to world peace and human progress, and their future co-operation,[34] expressing his hope for a "United World" that would combine the best qualities of "efficient America" and "spiritual India."[35] According to an eyewitness — Daya Mata, a direct disciple of Yogananda, who was head of the Self-Realization Fellowship from 1955 to 2010[36][37] — as Yogananda ended his speech, he read from his poem My India, concluding with the words "Where Ganges, woods, Himalayan caves, and men dream God—I am hallowed; my body touched that sod."[38] "As he uttered these words, he lifted his eyes to the Kutastha center (the Ajna Chakra or "spiritual eye"), and his body slumped to the floor."[32][39] His followers said that he entered mahasamadhi;[39][40][41][42][22] the cause of death was heart failure.[43] His funeral service, with hundreds attending, was held at the SRF headquarters atop Mt. Washington in Los Angeles. Rajarsi Janakananda, who Yogananda chose to succeed him as the new president of the Self-Realization Fellowship, "performed a sacred ritual releasing the body to God."[44]

According to the book Divine Interventions: True Stories of Mysteries and Miracles That Change Lives, for three weeks after his death Yogananda's body "showed no signs of physical deterioration and 'his unchanged face shone with the divine luster of incorruptibility.'" A notarized letter from Harry T. Rowe, the mortuary director, added: "The absence of any visual signs of decay … offers the most extraordinary case in our experience.... This state of perfect preservation of a body is, so far as we know from mortuary annals, an unparalleled one.... Yogananda's body was apparently in a phenomenal state of immutability.... No odor of decay emanated from his body at any time.... For these reasons we state again that the case of Paramahansa Yogananda is unique in our experience."[45] Yogananda's remains are interred at the Forest Lawn Memorial Park in the Great Mausoleum (normally closed off to visitors but Yogananda's tomb is accessible) in Glendale, California.[37]

Teachings[edit]

Giving a class in Washington, D.C. In 1917, in India Yogananda "began his life's work with the founding of a 'how-to-live'[46] school for boys, where modern educational methods were combined with yoga training and instruction in spiritual ideals." In 1920 "he was invited to serve as India's delegate to an International Congress of Religious Liberals convening in Boston. His address to the Congress, on 'The Science of Religion,' was enthusiastically received." For the next several years he lectured and taught across the United States. His discourses taught of the "unity of 'the original teachings of Jesus Christ and the original Yoga taught by Bhagavan Krishna.'"[47]

In 1920, he founded the Self-Realization Fellowship and in 1925 established in Los Angeles, California, USA, the international headquarters for SRF.[15][48][49] Yogananda wrote the Second Coming of Christ: The Resurrection of the Christ Within You and God Talks With Arjuna – The Bhagavad Gita to explain his belief in the harmony and oneness of original Christianity as taught by Jesus Christ and original Yoga as taught by Bhagavan Krishna; and to present that these principles of truth are the common scientific foundation of all true religions.[50]

Yogananda wrote down his Aims and Ideals for Self-Realization Fellowship /Yogoda Satsanga Society:[2][51]

- To disseminate among the nations a knowledge of definite scientific techniques for attaining direct personal experience of God.

- To teach that the purpose of life is the evolution, through self-effort, of man's limited mortal consciousness into God Consciousness; and to this end to establish Self-Realization Fellowship temples for God-communion throughout the world, and to encourage the establishment of individual temples of God in the homes and in the hearts of men.

- To reveal the complete harmony and basic oneness of original Christianity as taught by Jesus Christ and original Yoga as taught by Bhagavan Krishna; and to show that these principles of truth are the common scientific foundation of all true religions.

- To point out the one divine highway to which all paths of true religious beliefs eventually lead: the highway of daily, scientific, devotional meditation on God.

- To liberate man from his threefold suffering: physical disease, mental inharmonies, and spiritual ignorance.

- To encourage “plain living and high thinking”; and to spread a spirit of brotherhood among all peoples by teaching the eternal basis of their unity: kinship with God.

- To demonstrate the superiority of mind over body, of soul over mind.

- To overcome evil by good, sorrow by joy, cruelty by kindness, ignorance by wisdom.

- To unite science and religion through realisation of the unity of their underlying principles.

- To advocate cultural and spiritual understanding between East and West, and the exchange of their finest distinctive features.

- To serve mankind as one’s larger Self.

In his published work, The Self-Realization Fellowship Lessons, Yogananda gives "his in-depth instruction in the practice of the highest yoga science of God-realization. That ancient science is embodied in the specific principles and meditation techniques of Kriya Yoga."[30] Yogananda taught his students the need for direct experience of truth, as opposed to blind belief. He said that "The true basis of religion is not belief, but intuitive experience. Intuition is the soul's power of knowing God. To know what religion is really all about, one must know God."[2][50]

Echoing traditional Hindu teachings, he taught that the entire universe is God's cosmic motion picture, and that individuals are merely actors in the divine play who change roles through reincarnation. He taught that mankind's deep suffering is rooted in identifying too closely with one's current role, rather than with the movie's director, or God.[2]

He taught Kriya Yoga and other meditation practices to help people achieve that understanding, which he called Self-realization:[15]

Self-realization is the knowing – in body, mind, and soul – that we are one with the omnipresence of God; that we do not have to pray that it come to us, that we are not merely near it at all times, but that God's omnipresence is our omnipresence; and that we are just as much a part of Him now as we ever will be. All we have to do is improve our knowing.[52]

In his book, How you can talk with God, he claims that anyone can talk with God, if the person keeps persevering in the request to speak with God with devotion. He also claimed that God had spoken to him many times, apart from making miracles happen in his life. In the book, he claims that, "We may in a vision see a face of some divine/saintly being, or we may hear a Divine voice talking to us, and will know it is God. When our heart-call is intense, and we do not give up, God will come. It is important that we remove from our mind all doubt that God will answer."[53]

Kriya Yoga[edit]

The "science" of Kriya Yoga is the foundation of Yogananda's teachings. An ancient spiritual practice, Kriya Yoga is "union (yoga) with the Infinite through a certain action or rite (kriya). The Sanskrit root of kriya is kri, to do, to act and react." Kriya Yoga was passed down through Yogananda's spiritual lineage: Mahavatar Babaji taught the Kriya technique to Lahiri Mahasaya, who taught it to his disciple, Swami Sri Yukteswar Giri, Yogananda's Guru.[2]

Yogananda gave a general description of Kriya Yoga in his Autobiography:

"The Kriya Yogi mentally directs his life energy to revolve, upward and downward, around the six spinal centers (medullary, cervical, dorsal, lumbar, sacral, and coccygeal plexuses) which correspond to the twelve astral signs of the zodiac, the symbolic Cosmic Man. One-half-minute of revolution of energy around the sensitive spinal cord of man effects subtle progress in his evolution; that half-minute of Kriya equals one year of natural spiritual unfoldment".[2]

Sri Mrinalini Mata, the former president of SRF/YSS, said, "Kriya Yoga is so effective, so complete, because it brings God's love – the universal power through which God draws all souls back to reunion with Him – into operation in the devotee's life."[54]

Yogananda wrote in Autobiography of a Yogi that the "actual technique should be learned from an authorized Kriyaban (Kriya Yogi) of Self-Realization Fellowship /Yogoda Satsanga Society of India."[2]

Autobiography of a Yogi[edit]

In 1946, Yogananda published his life story, Autobiography of a Yogi.[15] It has since been translated into 45 languages. In 1999, it was designated one of the "100 Most Important Spiritual Books of the 20th Century" by a panel of spiritual authors convened by Philip Zaleski and HarperCollins publishers.[55] Autobiography of a Yogi is the most popular among Yogananda's books.[47] According to Philip Goldberg, who wrote American Veda, "the Self-Realization Fellowship which represents Yogananda's Legacy, is justified in using the slogan, "The Book that Changed the Lives of Millions." It has sold more than four million copies and counting".[56] In 2006, the publisher, Self-Realization Fellowship, honored the 60th anniversary of Autobiography of a Yogi "with a series of projects designed to promote the legacy of the man thousands of disciples still refer to as 'master'."[57]

Autobiography of a Yogi describes Yogananda's spiritual search for enlightenment, in addition to encounters with notable spiritual figures such as Therese Neumann, Anandamayi Ma, Vishuddhananda Paramahansa, Mohandas Gandhi, Nobel laureate in literature Rabindranath Tagore, noted plant scientist Luther Burbank (the book is 'Dedicated to the Memory of Luther Burbank, An American Saint'), famous Indian scientist Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose and Nobel laureate in physics Sir C. V. Raman. One notable chapter of this book is "The Law of Miracles", where he gives scientific explanations for seemingly miraculous feats. He writes: "the word 'impossible' is becoming less prominent in man's vocabulary."[2]

The Autobiography has been an inspiration for many people including George Harrison,[58] Ravi Shankar[59] and Steve Jobs. In the 2011 book Steve Jobs: A Biography the author writes that Jobs first read the Autobiography as a teenager. He re-read it in India and later while preparing for a trip, he downloaded it onto his iPad2 and then re-read it once a year ever since.[60] India national cricket team captain, Virat Kohli said that the Autobiography influenced his life in a positive manner and also urged everyone to read it.[61][62]

Claims of bodily incorruptibility[edit]

As reported in Time on August 4, 1952, Harry T. Rowe, Los Angeles Mortuary Director of the Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California, where Yogananda's body was received, embalmed and interred,[63] wrote in a notarized letter[2]

The absence of any visual signs of decay in the dead body of Paramahansa Yogananda offers the most extraordinary case in our experience... No physical disintegration was visible in his body even twenty days after death... No indication of mold was visible on his skin, and no visible drying up took place in the bodily tissues. This state of perfect preservation of a body is, so far as we know from mortuary annals, an unparalleled one... No odour of decay emanated from his body at any time...[64][65]

Because of two statements in Rowe's letter, some have questioned whether the term "incorruptibility" is appropriate. First, in his fourth paragraph he wrote: "For protection of the public health, embalming is desirable if a dead body is to be exposed for several days to public view. Embalming of the body of Paramahansa Yogananda took place twenty-four hours after his demise." In the eleventh paragraph he wrote: "On the late morning of March 26th, we observed a very slight, a barely noticeable, change – the appearance on the tip of the nose of a brown spot, about one-fourth inch in diameter. This small faint spot indicated that the process of desiccation (drying up) might finally be starting. No visible mold appeared however."[65]

Rowe continued in paragraphs fourteen and fifteen: "The physical appearance of Paramahansa Yogananda on March 27th just before the bronze cover for the casket was put into position, was the same as it was on March 7th. He looked on March 27th as fresh and unravaged by decay as he had looked on the night of his death. On March 27th there was no reason to say that his body had suffered any physical disintegration at all. For these reason we state again that the case of Paramahansa Yogananda is unique in our experience. On May 11, 1952, during a telephone conversation between an officer of Forest Lawn and an officer of Self-Realization Fellowship, the amazing story was brought out for the first time."[64]

Self-Realization Fellowship published Rowe's four-page notarized letter in its entirety in the May–June 1952 issue of its magazine Self-Realization.[66] From 1958 to the present it has been included in that organization's booklet Paramahansa Yogananda: In Memoriam.[37]

The location of Yogananda's crypt is in the Great Mausoleum, Sanctuary of Golden Slumber, Mausoleum Crypt 13857, Forest Lawn Memorial Park (Glendale).[67]

Self-Realization Fellowship /Yogoda Satsanga Society of India[edit]

Yogoda Satsanga Society of India (YSS) is a non-profit religious organization founded by Yogananda in 1917. In countries outside the Indian subcontinent it is known as the Self-Realization Fellowship. Yogananda's dissemination of his teachings is continued through this organization – the Self-Realization Fellowship (SRF) /Yogoda Satsanga Society of India (YSS).[56][36] Yogananda founded the Yogoda Satsanga Society of India in 1917 and then expanded it in 1920 to the United States naming it the Self-Realization Fellowship. In 1935, he legally incorporated it in the U.S. to serve as his instrument for the preservation and worldwide dissemination of his teachings.[68] Yogananda expressed this intention again in 1939 in his magazine Inner Culture for Self-Realization that he published through his organization:

Paramahansa Swami Yogananda renounced all his ownership rights in the Self-Realization Fellowship when it was incorporated as a nonprofit religious organization under the laws of California, March 29, 1935. At that time he turned over to the Fellowship all of his rights to and income from sale of his books, writings, magazine, lectures, classes, property, automobiles and all other possessions...[69]

SRF/YSS is headquartered in Los Angeles and has grown to include more than 500 temples and centers around the world. It has members in over 175 countries including the Self-Realization Fellowship Lake Shrine.[70] In India and surrounding countries, Paramahansa Yogananda's teachings are disseminated by YSS which has more than 100 centers, retreats, and ashrams.[36] Rajarsi Janakananda was chosen by Yogananda to become the President of SRF/YSS when he was gone.[15][71] Daya Mata, a religious leader and a direct disciple of Yogananda who was personally chosen and trained by Yogananda, was head of Self-Realization Fellowship /Yogoda Satsanga Society of India from 1955 to 2010.[16] According to Linda Johnsen, the new wave today is women, for major Indian gurus have passed on their spiritual mantle to women including Yogananda to the American-born Daya Mata[72] and then to Mrinalini Mata. Mrinalini Mata, a direct disciple of Yogananda, was the president and spiritual head of Self-Realization Fellowship /Yogoda Satsanga Society of India from January 9, 2011, until her death on August 3, 2017. She, too, was personally chosen and trained by Yogananda to help guide the dissemination of his teachings after his death.[36] On August 30, 2017, Brother Chidananda was elected as the next president in a unanimous vote by the SRF Board of Directors.[73] Yogananda incorporated the Self-Realization Fellowship as a nonprofit organization and reassigned all of his property including Mt. Washington to the corporation, thereby protecting his assets.[74]

On November 15, 2017, the President of India, Ram Nath Kovind visited the Yogoda Satsanga Society of India's Ranchi Ashram on its centennial anniversary in honor of the official release of the Hindi translation of Yogananda's book God Talks with Arjuna: The Bhagavad Gita.[75][76][77][78]

Commemorative stamps[edit]

India released a commemorative stamp in honor of Yogananda in 1977.[79] "Department of Post issued a commemorative postage stamp on the occasion of the twenty‑fifth anniversary of Yogananda's passing in honor of his far‑reaching contributions to the spiritual upliftment of humanity. "The ideal of love for God and service to humanity found full expression in the life of Paramahansa Yogananda. Though the major part of his life was spent outside India, still he takes his place among our great saints. His work continues to grow and shine ever more brightly, drawing people everywhere on the path of the pilgrimage of the Spirit."[80][81]

A 2017 stamp of India, with the Yogoda Satsanga Sakha Math at Ranchi in the background On March 7, 2017, the Prime Minister of India, Narendra Modi, released another commemorative postage stamp honoring the 100th anniversary of the Yogoda Satsanga Society of India.[82] Prime Minister Modi at Vigyan Bhawan in New Delhi appreciated Yogananda for spreading the message of India's spirituality in foreign shores. He said that though Yogananda left the shores of India to spread his message, he always remained connected with India.[83]

Direct disciples[edit]

Bibliography[edit]

See also[edit]

- ^ "Yogi of Yogis Sri Paramahansa Yogananda visited our city". Star of Mysore. June 20, 2017. Retrieved January 5,2018.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Autobiography of a Yogi, 1997 Anniversary Edition. Self-Realization Fellowship (Founded by Yogananda) yogananda.org

- ^ Wadhwa, Hitendra (June 21, 2015). "Steve Jobs's Secret to Greatness: Yogananda". Inc.com. Retrieved October 8,2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Meares, Hadley (August 9, 2013). "From Hip Hotel to Holy Home: The Self-Realization Fellowship on Mount Washington". KCET. Retrieved October 8, 2019.

- ^ Chidan; Jun 19, Rajghatta | TNN | Updated; 2019; Ist, 12:01. "In America and across the world, India reclaims its yoga heritage – Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved October 8, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Goldberg, Philip (March 7, 2012). "The Yogi Of The Autobiography: A Tribute To Yogananda". HuffPost. Retrieved October 8, 2019.

- ^ "HarperSanFrancisco, edited by Philip Zaleski 100 Best Spiritual Books of the 20th Century".

- ^ Segall, Laurie (September 10, 2013). "Steve Jobs' last gift". CNNMoney. Retrieved October 8, 2019.

- ^ Goldberg, Philip (2018). The Life of Yogananda. Hay House, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4019-5218-1

- ^ Bowden, Henry Warner (1993). Dictionary of American Religious Biography. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-27825-3. p. 629.

- ^ "Yogi and the USA". The Statesman. September 9, 2018. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Sananda Lal Ghosh, (1980), Mejda, Self-Realization Fellowship, p.3

- ^ Newcombe, Suzanne (2017). "The Revival of Yoga in Contemporary India" (PDF). Religion. Oxford Research Encyclopedias. 1. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.253. ISBN 9780199340378.

- ^ "Swami yogananda giri speaks on "the inner life". ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Boston Globe p.9. Boston, MA. March 5, 1921.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Melton, J. Gordon, Martin Baumann (2010). Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598842043.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Hevesi, Dennis (December 3, 2010). "Sri Daya Mata, Guiding Light for U.S. Hindus, Dies at 96". New York Times. New York, NY.

- ^ Boston Meditation Group Historical Committee. In The Footsteps of Paramahansa Yogananda: A guidebook to the places in and around Boston associated with Yoganandaji

- ^ Sister Gyanamata "God Alone: The Life and Letters of a Saint" p. 11

- ^ Lewis Rosser, Brenda (1991). Treasures Against Time. Borrego Publications. p. Foreword p. xiii. ISBN 978-0962901607.

- ^ "The Best Yoga Film of 2014: Get a Sneak Peak Here". HuffPost. October 20, 2014. Retrieved May 8, 2019.

- ^ National Archives Catalog, Department of Commerce and Labor. Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization. 1906–1913 and 1913-6/10/1933 (Predecessor) & 1893 – 1957. Confidential File on Swami Yogananda, Alleged Hindu Religious Leader, Whose Fraudulent and Moral Practices Rendered Him an Undesirable Alien, from 1926–1937. Series: Subject and Policy Files, 1893 – 1957.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Goldberg, Philip (2018). The Life of Yogananda. California: Hay House, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4019-5218-1.

- ^ Biography of a Yogi(2017), by Anya Foxan, pg 106-108

- ^ Yogananda, Paramahansa (2004). The Second Coming of Christ (book) / Volume I / Jesus Temptation in the wilderness / Discourse 8 / Mattew 4:1–4. Self-Realization Fellowship. pp. 166–167. ISBN 9780876125557.

- ^ "Paramahansa means "supreme swan" and is a title indicating the highest spiritual attainment." Miller, p. 188.

- ^ Melton, J. Gordon (2011). Religious Celebrations. ABC-CLIO. p. 512. ISBN 978-1598842050.

- ^ Self-Realization Fellowship: Encinitas Retreat. Yogananda.org. Retrieved on March 25, 2019.

- ^ Self-Realization Fellowship. Encinitas Temple. Retrieved on March 25, 2019.

- ^ Creating Self-Realization Fellowship Lessons, Temples, Retreats and writing his Autobiography of a Yogi. yogananda.org. Retrieved on December 13, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Yogananda, Paramahansa (1995). God Talks With Arjuna – The Bhagavad Gita p.xii/1130. Los Angeles, CA: Self-Realization Fellowship. ISBN 978-0-87612-030-9.

- ^ Mata, Mrinalini. In His Presence: Remembrances of Life With Paramahansa Yogananda (DVD). Self-Realization Fellowship. ISBN 978-0-87612-517-5.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Mata, Daya (1990). Finding the Joy Within, 1st ed. Los Angeles, CA: Self-Realization Fellowship, p 256

- ^ Bhandari, P.L. (2013) How Not To Be A Diplomat: Adventures in the Indian Foreign Service Post-Independence. The Quince Tree Publishing. ISBN 978-0957697904

- ^ Kriyananda, Swami (Donald Walters) (1977). The Path: Autobiography of a Western Yogi. Ananda Publications. ISBN 978-0916124120.

- ^ Miller, p. 179.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d About SRF: Lineage and Leadership. yogananda.org

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Self-Realization Fellowship (2001) (1986). Paramahansa Yogananda: In Memoriam: Personal Accounts of the Master's Final Days. Los Angeles, CA. ISBN 978-0-87612-170-2.

- ^ Mata, Daya (Spring 2002). "My Spirit Shall Live On: The Final Days of Paramahansa Yogananda". Self-Realization Magazine.

- ^ Jump up to:a b "Guru's Exit – TIME". Time. August 4, 1952. Archived from the original on February 12, 2008. Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- ^ "The Life Of Yogananda: Guru, Author Of 'Autobiography of a Yogi'". Huffpost.com. Huffington Post. September 2015. Retrieved November 23, 2019.

- ^ "Yogananda Facts: The American Missionary". yourdictionary.com/. Your Dictionay: Biography. Retrieved November 23, 2019.

- ^ "A Beloved World Teacher: Final Years and Mahasamadhi". Yogananda.org. Self-Realization Fellowship. Retrieved November 23, 2019.

- ^ "Incorruptibility (Of dead bodies)".

- ^ "Hundreds Pay Tribute at Rites for Yogananda". ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, CA. March 12, 1952.

- ^ Millman, Dan; Childers, Doug (November 4, 2000). Divine Interventions: True Stories of Mysteries and Miracles That Change Lives. Rodale. ISBN 978-1-57954-338-9.

- ^ Yogananda, Paramahansa (1925). "The Balanced Life - Curing Mental Abnormalities" (PDF). Yogananda Parenting. Retrieved March 26, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Goldberg, Philip (2012). The Autobiography of a Yogi: A Tribute to Yogananda. Huff Post Religion.

- ^ Yogananda, Paramahansa (2004). The Second Coming of Christ: The Resurrection of the Christ Within You p.1566. Los Angeles, CA: Self-Realization Fellowship. ISBN 978-0-87612-555-7.

- ^ Kress, Michael (2001). Publishers Weekly: Meditation is the message. New York: Cahners Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier, Inc.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Watanabe, Teresa (November 12, 2004). "A Hindu's Perspective on Christ and Christianity". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, CA.

- ^ "Aims & Ideals of Self-Realization Fellowship". Retrieved February 9, 2008.

- ^ Yogananda, Paramahansa (2004). The Second Coming of Christ: The Resurrection of the Christ Within You p. xxi. Los Angeles, CA: Self-Realization Fellowship. ISBN 978-0-87612-555-7.

- ^ Paramahansa Yogananda (1998). How You Can Talk with God. Self-Realization Fellowship Publishers. ISBN 978-0-87612-168-9.

- ^ Mrinalini Mata (2011). Self-Realiztion Magazine: The Blessings of Kriya Yoga in Everyday Life. Los Angeles, CA: Self-Realization Fellowship.

- ^ "HarperCollins 100 Best Spiritual Books of the Century".

- ^ Jump up to:a b Goldberg, Philip (2012). American Veda. Harmony; 1 edition (November 2, 2010): 109.

- ^ Sahagun, Louis (August 6, 2006). "Guru's Followers Mark Legacy of a Star's Teachings". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Wright, Gary (2014). Dream Weaver: A Memoir; Music, Meditation, and My Friendship with George Harrison. TarcherPerigee.

- ^ O'Mahony, John (June 3, 2008). "A Hodgepodge of Hash, Yoga and LSD – Interview with Sitar giant Ravi Shankar". The Guardian. Retrieved August 14, 2017.

- ^ Isaacson, Walter (2011). Steve Jobs: A Biography. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4516-4853-9.

- ^ "Virat Kohli reveals his source of inspiration: 'Autobiography of a Yogi' by Paramhansa Yogananda - Sports News, Firstpost". Firstpost. February 19, 2017. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ "Virat Kohli shares autobiography behind his success". The Indian Express. February 18, 2017. Retrieved October 3,2020.

- ^ "Guru's Exit". Time. August 4, 1952. Archived from the original on November 25, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Forest Lawn Memorial-Park; Harry T. Rowe; Mortuary Director (May 16, 1952). Paramahansa Yogananda's Mortuary Report. Los Angeles, CA.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Rowe, Harry T. "Paramahansa Yogananda's Mortuary Report" (PDF). Forest Lawn Memorial Park.

- ^ "Self-Realization Magazine". Self-Realization : Magazine Devoted to Healing of Body, Mind, and Soul. Los Angeles: Self-Realization Fellowship. 1952. ISSN 0037-1564.

- ^ "Paramahansa Yogananda's Crypt Location". Find a Grave.

- ^

Works related to SRF Articles of Incorporation 1935 at Wikisource

Works related to SRF Articles of Incorporation 1935 at Wikisource - ^ Self-Realization Fellowship (1939). Inner Culture for Self-Realization. 12. p. 30.

- ^ "Locations of SRF/YSS centers & temples". Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- ^ Self-Realization Fellowship (1996). Rajarsi Janakananda: A Great Western Yogi. Self-Realization Fellowship Publishers. ISBN 0-87612-019-2.

- ^ Sharma, Arvind (1994). Today's Women in World Religions. SUNY Press.

- ^ yogananda.org "Brother Chidananda Elected President and Spiritual Head of SRF/YSS". Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ Foxan, Anya (2017). Biography of a Yogi. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0190668051.

- ^ "President of India Ram Nath Kovind visited Ranchi". India. November 15, 2017.

- ^ Mishra, Sudhir Kumar (November 16, 2017). "Ashram charms First Citizen". Telegraph India.

- ^ "President of India Visits YSS Ranchi Ashram – God Talks With Arjuna in Hindi Is Released". yogananda.org. November 15, 2017.

- ^ "President, Ram Nath Kovind addresses at Yogoda Satsanga Society of India in Ranchi". Amirapress.com. India. Newspoint Tv. November 16, 2017.

- ^ "A commemorative postage stamp on the Death Anniversary of Paramahansa Yogananda". Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- ^ "Indian Philatelic Stamps". January 5, 2017. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- ^ "Indian Postage Stamps – 1977". January 5, 2017. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- ^ "PM releases commemorative postage stamp on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of Yogoda Satsanga Society of India". Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- ^ "PM Narendra Modi releases commemorative stamp on Yogoda Satsanga Society". Archived from the original on March 12, 2017. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

References[edit]

- Boston Meditation Group Historical Committee (1989). In The Footsteps of Paramahansa Yogananda: A guidebook to the places in and around Boston associated with Yoganandaji. Boston, MA.

- Bowden, Henry Warner (1993). Dictionary of American Religious Biography. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-27825-9.

- Daya, Mata (1990). Finding the Joy Within. Self-Realization Fellowship. ISBN 978-0-87612-288-4.

- Forest Lawn Memorial Park; Harry T. Rowe; Mortuary Director (May 16, 1952). Paramahansa Yogananda's Complete Mortuary Report. Los Angeles, CA.

- Ghosh, Sananda Lal (1980). Mejda: The Family and the Early Life of Paramahansa Yogananda. Self-Realization Fellowship Publishers. ISBN 978-0-87612-265-5.

- Goldberg, Philip (2012). The Autobiography of a Yogi: A Tribute to Yogananda. Huff Post Religion.

- Goldberg, Philip (2012). American Veda. Harmony; 1 edition (November 2, 2010): 109.

- Isaacson, Walter (2001). Steve Jobs: A Biography. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4516-4853-9.

- Jordan, Frank C., Secretary of State of California (1935). Articles of Incorporation of the Self Realization Fellowship Church. Los Angeles CA: State of California.

- Kress, Michael (March 26, 2001). "Meditation is the Message". Publishers Weekly. New York. Cahners Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier.

- Kriyananda, Swami (1977). The Path: Autobiography of a Western Yogi. Crystal Clarity Publishers. ISBN 978-0-916124-11-3.

- J. Gordon Melton, Martin Baumann (2010). Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598842043.

- Miller, Timothy (1995). America's Alternative Religions. Borrego Publications; 1st edition (1991). ISBN 978-0-7914-2397-4.

- Mrinalini Mata (2011). Self-Realization Magazine: The Blessings of Kriya Yoga in Everyday Life. Los Angeles, CA: Self-Realization Fellowship.

- Rosser, Brenda Lewis (2001). Treasures Against Time: Paramahansa Yogananda with Doctor and Mrs. Lewis (2nd ed.). Borrego Springs, CA: Borrego Publications. ISBN 978-0-9629016-1-4.

- Rowe, Harry T. "Paramahansa Yogananda's Mortuary Report" (PDF). Forest Lawn Memorial Park.

- Self-Realization Fellowship (1939). "Inner Culture for Self-Realization". Los Angeles, CA: Volume 12, page 30.

- Self-Realization Fellowship (1952). "Self-Realization Magazine". Los Angeles, CA: Volume 24, No. 22.

- "Self-Realization Fellowship website". Retrieved November 24, 2011.

- Sahagun, Louis (August 6, 2006). "Guru's Followers Mark Legacy of a Star's Teachings". Los Angeles Times.

- Thomas, Wendell (1930). Hinduism Invades America. New York, NY: The Beacon Press, Inc.

- Yogananda, Paramahansa (1997). Autobiography of a Yogi. Los Angeles, CA: Self-Realization Fellowship. ISBN 978-0-87612-086-6.

- Yogananda, Paramahansa (1995). God Talks With Arjuna – The Bhagavad Gita. Los Angeles, CA: Self-Realization Fellowship. ISBN 978-0-87612-030-9.

- Yogananda, Paramahansa (1997). Journey to Self-Realization, Discovering the Gifts of the Soul. Los Angeles, CA: Self-Realization Fellowship. ISBN 978-0-87612-255-6.

- Zaleski, Philip (1984). The 100 Best Spiritual Books of the Century. San Francisco: Harper Collins.

External links[edit]

Credit...Carl Mydans/The LIFE Picture Collection, via Getty Images

Credit...Carl Mydans/The LIFE Picture Collection, via Getty Images Credit...Clifford Coffin/Conde Nast, via Getty Images

Credit...Clifford Coffin/Conde Nast, via Getty Images Credit...Ulf Andersen/Getty Images

Credit...Ulf Andersen/Getty Images Credit...Associated Press

Credit...Associated Press Credit...Ulf Andersen/Gamma-Rapho, via Getty Images

Credit...Ulf Andersen/Gamma-Rapho, via Getty Images Credit...Robert W. Kelley/The LIFE Picture Collection, via Getty Images

Credit...Robert W. Kelley/The LIFE Picture Collection, via Getty Images Credit...Bettmann/Getty Images

Credit...Bettmann/Getty Images Credit...Bettmann/Getty Images

Credit...Bettmann/Getty Images Credit...William E. Sauro/The New York Times

Credit...William E. Sauro/The New York Times Credit...Damon Winter/The New York Times

Credit...Damon Winter/The New York Times Credit...Bettmann/Getty Images

Credit...Bettmann/Getty Images Credit...Shaban Athuman for The New York Times

Credit...Shaban Athuman for The New York Times Credit...Oliver Morris/Getty Images

Credit...Oliver Morris/Getty Images Credit...Ulf Andersen/Getty Images

Credit...Ulf Andersen/Getty Images Credit...Henry Clarke/Conde Nast, via Getty Images

Credit...Henry Clarke/Conde Nast, via Getty Images Credit...Horst Tappe/Hulton Archive, via Getty Images

Credit...Horst Tappe/Hulton Archive, via Getty Images Credit...Ian Patterson for The New York Times

Credit...Ian Patterson for The New York Times Credit...Bettmann/Getty Images

Credit...Bettmann/Getty Images Credit...Krista Schlueter for The New York Times

Credit...Krista Schlueter for The New York Times Credit...Marco Delogu for The New York Times

Credit...Marco Delogu for The New York Times Credit...Franck Smith/Sygma, via Getty Images

Credit...Franck Smith/Sygma, via Getty Images Credit...Sunny Shokrae for The New York Times

Credit...Sunny Shokrae for The New York Times Credit...Andre D. Wagner for The New York Times

Credit...Andre D. Wagner for The New York Times Credit...Mike Cohen for The New York Times

Credit...Mike Cohen for The New York Times