Book reviews

Yoneyama, Shoko. 2019.

Animism in Contemporary Japan: Voices for

the Anthropocene from Post-Fukushima Japan. Abingdon: Routledge. xi + 250

pp. Hb.: £115.00.

ISBN: 9781138228030;

Ebook.: £20.00. ISBN: 9781315393902.

From the mid-1950s, people living in

fishing villages around Minamata in western Japan began dying terrible deaths

from mercury poisoning traced to wastewater from a factory in the town.

Thousands of people remain affected by one of the world’s worst criminal cases

of industrial pollution. The Minamata incident provides the starting point for

this new book by sociologist Shoko Yoneyama. Given that another awful case of

pollution began at Fukushima in March 2011, how are we to understand and

respond to such horrors? This book analyses four Japanese intellectuals, three

of whom have been directly involved with Minamata. In all four cases, the

author Yoneyama argues that “animism” has formed the basis of their responses

to Minamata and other crises of modernity.

This volume is published in Routledge’s Contemporary Japan Series, but the

author insists that her aim is not to ‘describe Japanese culture by using the

notion of animism or anything else for that matter’ (p. 24). Instead, Yoneyama

aims to focus on what she terms the “grassroots animism” of four individuals

who happen to be Japanese. We will discuss below whether Yoneyama succeeds in

this objective of escaping the overdetermined space (aka ideology) of Japanese

animism, but it will be useful to begin this review by attempting to explain

the significance of her approach. For many readers in Japanese Studies, the

term “animism” will immediately bring to mind the reactionary atavistic

writings of philosopher Takeshi Umehara (1925-2019), the first director of the

International Research Center for Japanese Studies (an institution known

colloquially as the Nichibunken).

From the 1980s, Umehara began to propound a vision of Japanese culture based on

deep animist roots. This vision was taken up by several of Umehara’s former

associates at the Nichibunken, especially Yoshinori Yasuda. In her

Introduction, Yoneyama (pp. 20-22) provides a short but incisive critique of

the writings of this group, which we might call the Alt-Nichibunken. Umehara’s animism was effectively an attempt at

building a ‘State Animism’. Even though Umehara himself was critical of the

appropriation of Japan’s cultural traditions by State Shinto in the late 19th

and early 20th centuries, his response was to create the

fantasy of a homogenous “forest civilisation” closely linked to the Japanese

state and emperor. In this book, Yoneyama attempts to distance herself from this

view of animism as nationalist discourse; in fact, she chooses to analyse the

writings of four individuals who have taken “intellectual journeys” which have

positioned themselves ‘the furthest away one can get from presenting a national

discourse’ (p. 22).

The four substantive chapters of the volume discuss the

work of Masato Ogata (b. 1953), a fisherman, activist and writer in Minamata;

Michiko Ishimure (1927-2018), a writer best known for her Paradise in the Sea of Sorrow: Our Minamata Disease; sociologist

Kazuko Tsurumi (1918-2006); and film director Hayao Miyazaki (b. 1941). These

are all significant figures in post-war Japanese letters but do they, in fact,

share an animist worldview? As discussed below, Ogata’s view of the world could

certainly be called ecological, but

Yoneyama notes that he does not use the word “animism” (p. 54). Similarly,

Ishimure rarely refers to animism, though Yoneyama stresses that ‘an animistic

theme runs

189

Anthropological Notebooks,

XXV/1, 2019

through her literary work’ (p. 81).

In contrast to Ogata and Ishimure, Miyazaki identifies his artistic philosophy

as influenced by animism, although he denies its religious nature, saying ‘I do

like animism. I can understand the idea of ascribing character to stones and

wind. But I don’t want to laud it as a religion’ (p. 180). Of the four

individuals discussed here, it is the academic Tsurumi who was most explicit

about her attempts to recover animism as a ‘disappearing “way of knowing” that [she] discovered in Minamata’ (p. 143) and to

use that animism to build a new type of social science. The animism discussed

in Yoneyama’s book is, as the author herself admits (p. 223), not a religion (however one defines

that) and rarely involves any rituals, although Ogata (p. 56) mentions several

customs performed by fishermen in Minamata. Rather than “religion”, Yoneyama

offers the term “postmodern animism”, defined as a ‘philosophy of the

life-world’ (p. 224). Suddenly, “animism in contemporary Japan” looks more like

an extension of phenomenology and the Romantic concern with the environment as

a world of experience.

What, then, if not animism? My view is that

analysing the four individuals in terms of ecology

would have been more interesting and might have brought their ideas further

away from the virally reproduced aura of Japanese Nature. The four individuals

possess rather different views on nature and ecology, although all share the

Romantic idea of the environment as a life-world that can transform self and society.

Kazuko Tsurumi has by far the most academic take of the four, discovering

animism in the beliefs of people in Minamata and being herself ‘spiritually

awakened’ (p. 116) to its potential in developing a critique of modernity.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of Tsurumi’s work to appear in this volume

is her discussion of the ecologist Kumagusu Minakata (1867-1941). Minakata’s

work on slime moulds has potential to link with recent debates in environmental

philosophy—such as Timothy Morton’s writings on queer ecology and the “strange

stranger”—yet both Tsurumi and Yoneyama limit themselves to connections with

esoteric Buddhism and animism.

Hayao Miyazaki’s interest in nature began with him

reading Sasuke Nakao’s “broadleaf evergreen forest hypothesis”, first published

in 1966. This theory, which links western Japan with south China and Southeast

Asia in an Austrian ethnology-inspired Kulturkreis,

provided Miyazaki with a liberating means to understand that Japan ‘was

actually connected to the wider world beyond borders and ethnic groups’ (p.

177). As well as an escape from nationalism, the theory also stimulated

Miyazaki to ‘believe that greenery was beautiful’, in stark contrast to his

younger days when he ‘thought that greenery was nothing but a symbol of

poverty’ (p. 179). As a result, Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli attempts to

incorporate aspects of the landscape including ‘weather, time, rays of light,

plants, water, and wind’ in its films (p. 176). Miyazaki’s comment that, ‘Human

relationships are not the only thing that is interesting’ checks one of

Lawrence Buell’s boxes for classification as an environmental text, but his

overall approach seems to limit the environment to “greenery”, implying that,

say, the depicted urban landscapes or the un-depicted

train journeys in Yasujirō’s Ozu’s film Tokyo

Story do not equally constitute environment. One critic has said that

‘Miyazaki has “baptized a whole generation” with an animistic imagination’ (p.

159), but in what way is Totoro more animistic than Winnie the Pooh—except that

the former is portrayed within a Japanese context that invites

190

Book reviews

cultural readings associated with animism

and folk Shinto?

Michiko Ishimure is well known as one of Japan’s foremost

environmental writers, and her work has been much discussed within

ecocriticism. Ishimure’s writings sometimes assign “personhood to nonhumans”

including “crow-women” and yamawaros

mountain spirits (pp. 82-84). The discussion here in Chapter 2 is unclear as to

how Ishimure perceived the relations between human and nonhuman persons.

Certain passages from her writings reproduced here suggest that nonhuman

persons inhabited another world deep in the mountains and dark forests.

Elsewhere, Ishimure claims that in the ‘pre-pollution era of the Shiranui Sea,

people, nature (including animals), and kami

coexisted closely and intermingled with each other’ (p. 83). The trajectory is

from living in the world to thinking about the world (p. 93), the implication

being that ecological relations only existed in a stage prior to modernity.

With his anxieties over consumerism, Masato Ogata is

perhaps the most ecological of the four thinkers discussed here. Throwing his

television out of his door into the front garden (‘You beast! How dare you

break into my house and order us around. Go there! Buy this!’ [p. 49]), Ogata

understands the close link between consumerism and ecology. Ogata’s book Chisso wa watashi de atta [‘I was

Chisso’] should be an essential text for the Anthropocene, encapsulating so

beautifully as it does the irony of the sudden realisation that it is we who

have been destroying the world all along.

Other readers will no doubt have different takes on the

ecology of the four people discussed in this volume, but my point is that

thinking about their differences tell us a great deal about views of the

environment in post-war Japan. By contrast, forcing all four into a box

labelled ‘animism’ misses much that is interesting. Animism in Contemporary Japan succeeds in breaking and entering the

‘State Animism’ of the Alt-Nichibunken, but in my view, it is unable to achieve

two of its objectives: escaping the dark star pull of Japanese culture and

changing the world.

Let us take Japanese culture first. Yoneyama insists that

her aim is not to critique the West or to develop binary East/West oppositions

of the type found in the works of Umehara and Yasuda. The book indeed adopts a

very different tone from the virulently anti-Western/anti-Christian tracts of

Yasuda in particular (cf. the quote on p. 21 of this volume). However, ‘the

West’ is primarily noticeable here by its absence; there is almost no

discussion of how the animism of the four individuals might resonate with

spiritual ideas beyond Japan. A rare exception is a brief mention of Saint

Francis of Assisi who Yoneyama mistakenly describes as a ‘medieval heretic’ (p.

24)—although his ideas may have been unusual for his time, he would hardly have

been canonised had he been a heretic! In assuming that the diverse writings and

ideas analysed here can be glossed as ‘animism in Japan’, Yoneyama plays down

the political functions of that phenomenon. Grassroots animism, like folk

Shinto, is assumed to be egalitarian and apolitical. For example, in Table 3.2

(p. 130), the “Ideological function” of folk Shinto is listed as “Irrelevant”.

Such characterisations seem to me to overlook the agency of individuals

participating in the social lives of local communities and local spirits. The

work of anthropologist Rane Willerslev, for example, shows how Yukaghir hunters

in Siberia regard animism as an ideology to be argued with and negotiated

within.

191

Anthropological Notebooks,

XXV/1, 2019

What, then, about changing the world? Like many

before her, Yoneyama seems to believe that Japan’s unusual place within

modernity gives the country a unique role in responding to the crises of that

same modern system. Yoneyama claims that, ‘the extent to which Japan has “never

been modern” is greater than that of the advanced societies in the West’ (p.

4). Similarly, for Antonio Negri, ‘Japan’s powerful cultural traditions which

manage to co-exist with super-modernity have the potential to solve [the] conundrum’

of ‘finding a new way to coexist with nature’ (p. 205). That Japan’s amalgam of

old and new provides a privileged position from which to build a new world

order was exactly the point made by Umehara. Changing the world has always been

the holy grail of what Timothy Morton calls the “religious style” of being

ecological, but the grassroots animism of Japan—however important to those people at the level of the grassroots—is

unlikely to find a broader resonance without a fundamental reframing of its

terms of reference.

By now, it will be clear that I find this book’s use of

animism as a way of encapsulating the diverse and fascinating ideas discussed

here as rather unconvincing. A sociological analysis of animism as a response

to power or a focus on ecology (or environmental philosophy) would, in my view,

have given the book a wider appeal. Despite this reservation, however, I found Animism in Contemporary Japan to be a

stimulating and well-written work which provides a wonderful way to think

through many important issues about ecology, society and contemporary Japan.

The arguments of the volume resonate strongly with several key Anthropocene

debates, especially those about responsibility, poetics, and civil society. I

hope this book will be widely read and debated, both within Japanese Studies

and beyond.

MARK J. HUDSON

Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History (Germany)

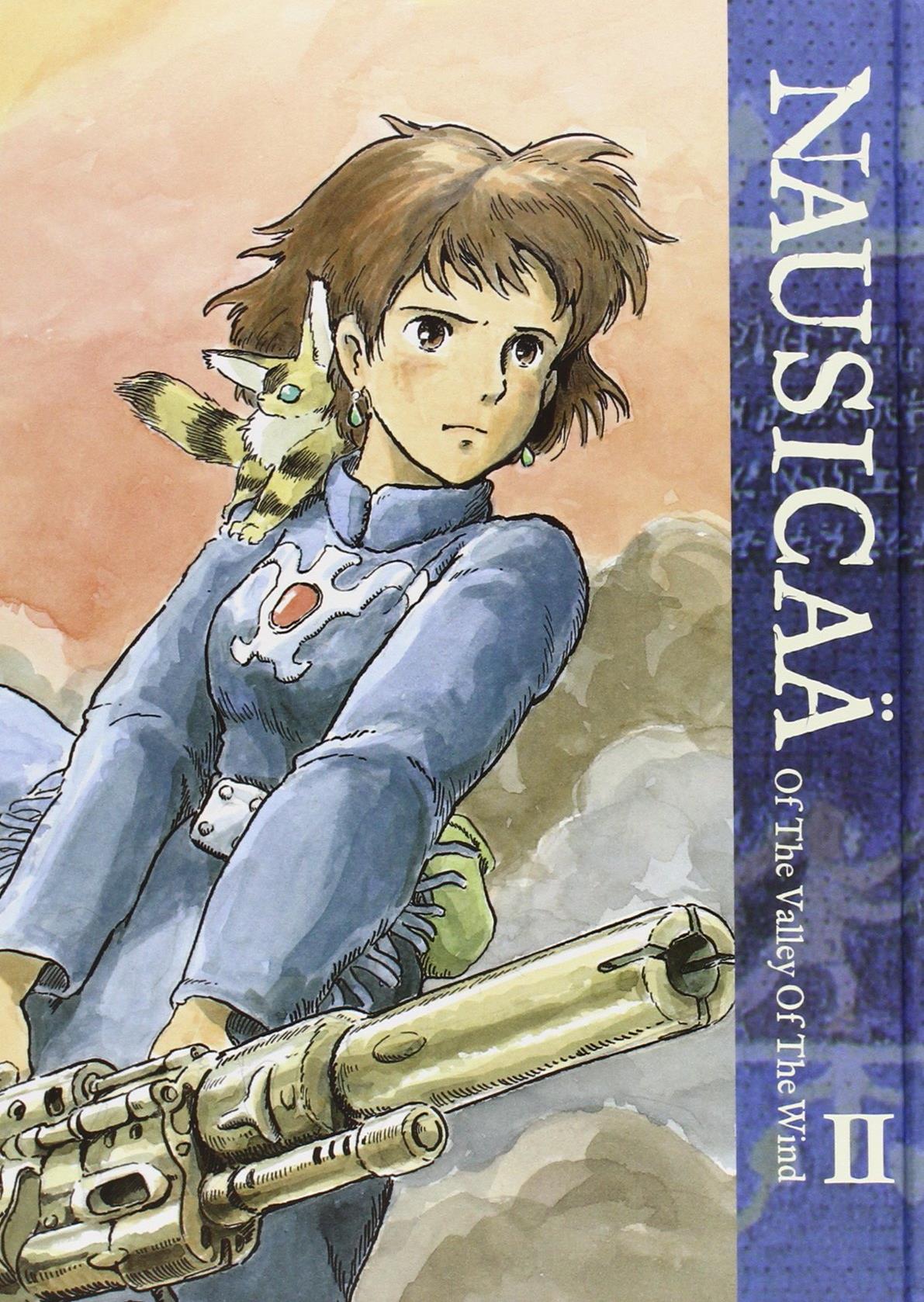

narratives and state Shintoism, she posits a theory of endogenous development (p118, p125) based on ‘place consciousness’, its own ‘way of knowing’ (p143), honouring folk Shintoism and its spiritual connection to ‘little kami’ (spirits, deities) (p26). Animation director Miyazaki Hayao was inspired to make the anime film Nausicaä by the Minamata disaster (p4-5).

narratives and state Shintoism, she posits a theory of endogenous development (p118, p125) based on ‘place consciousness’, its own ‘way of knowing’ (p143), honouring folk Shintoism and its spiritual connection to ‘little kami’ (spirits, deities) (p26). Animation director Miyazaki Hayao was inspired to make the anime film Nausicaä by the Minamata disaster (p4-5).