POSTMODERN ANIMISM FOR A NEW MODERNITY

How to reconcile with a post-industrial world and its self-imposed disasters

2019-07-05

By Chilla Bulbeck, Co-convenor, Greens (WA)

A review of Shoko Yoneyama (2019) Animism in Contemporary Japan: Voices for the Anthropocene from Post-Fukushima Japan Routledge: Oxon and New York

‘March 2011 in Fukushima turned out to be a silent spring, the depth of which no one may ever know’, begins Shoko Yoneyama (p1) in an evocative mourning for damaged life. ‘Peach trees blossomed and horsetail shot up from the snow, but all were irradiated’. ‘Random genetic mutations began amongst tiny pale-grass-blue butterflies’, made visible as ‘abnormalities in their eyes, wings and antennas’.

The catastrophe of Fukushima occurred in the same year China surpassed Japan as the world’s second largest economy marking the end of Japan’s period of ‘super-modernisation’ (p10). The less well-known disaster of Minamata disease ushers in this period. The disease was officially ‘discovered’ in 1956, at the beginning of Japan’s post-war high economic growth period (p10).

Writing in this period between Minamata and Fukushima are four Japanese intellectuals who challenge Japan’s materialist expansion through the intellectual lens and lived experience of ‘postmodern animism’ or ‘new animism’.

Fisherman Ogata Masato lost his family to Minamata disease, and wrestled with his response to this tragedy (more below). Writing by environmental novelist Ishimure Michiko, described as the ‘Rachel Carson of Japan’, ‘connect(s) Minamata to society at large’ (p86-87). Tsurumi Kazuko delves into animism when the tragedy of the Minamata victims is beyond her sociological tool-box (p113). From a critique of modernisation, national

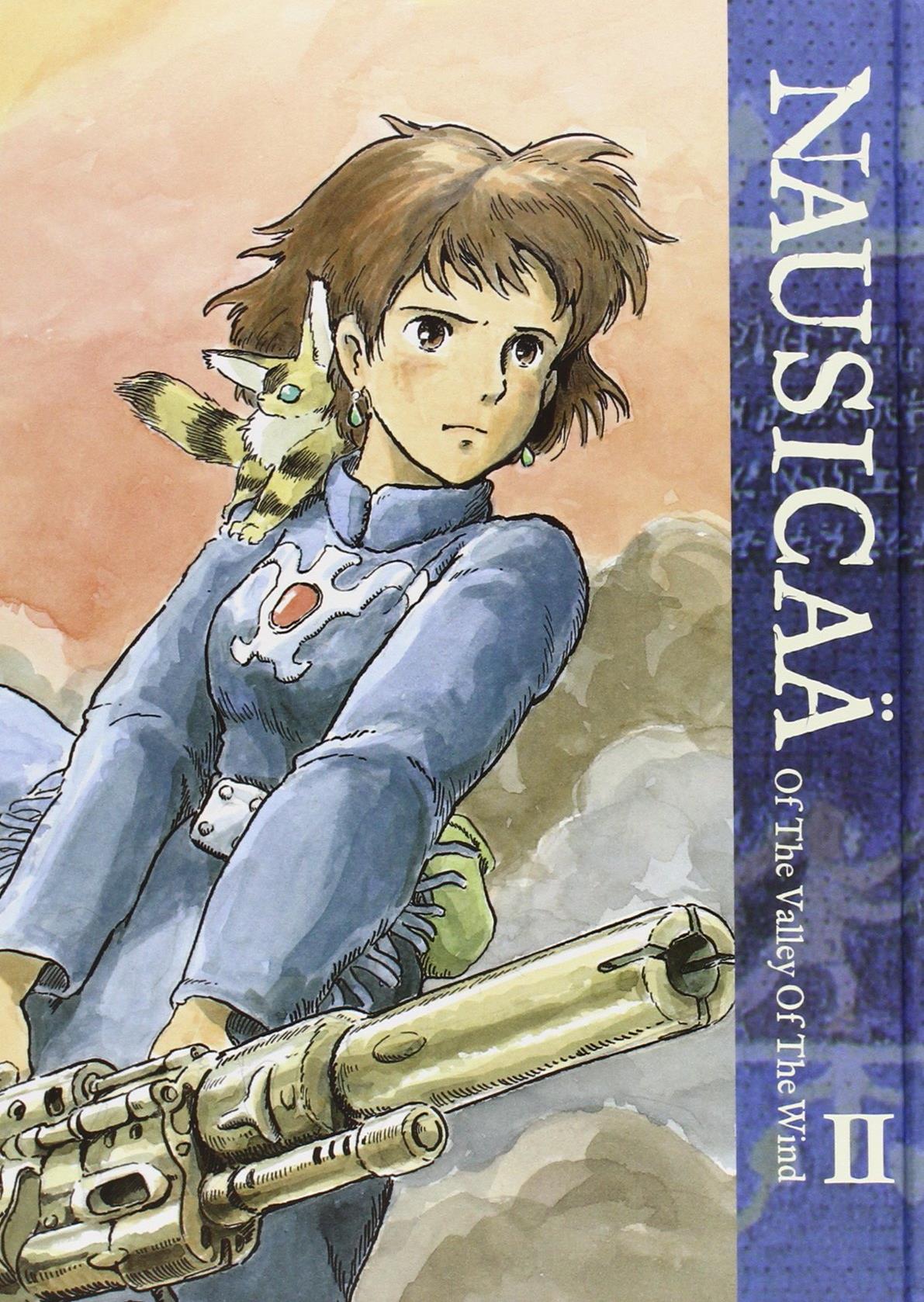

narratives and state Shintoism, she posits a theory of endogenous development (p118, p125) based on ‘place consciousness’, its own ‘way of knowing’ (p143), honouring folk Shintoism and its spiritual connection to ‘little kami’ (spirits, deities) (p26). Animation director Miyazaki Hayao was inspired to make the anime film Nausicaä by the Minamata disaster (p4-5).

narratives and state Shintoism, she posits a theory of endogenous development (p118, p125) based on ‘place consciousness’, its own ‘way of knowing’ (p143), honouring folk Shintoism and its spiritual connection to ‘little kami’ (spirits, deities) (p26). Animation director Miyazaki Hayao was inspired to make the anime film Nausicaä by the Minamata disaster (p4-5). I read Yoneyama’s book in the shadow of our own disaster, the 2019 Federal ‘climate emergency’ election. The result further entrenches the fault-lines dividing us: an increased vote for the Greens in the Senate, and also for white supremacist parties and more fossil fuel extraction, particularly in the lower house; a vote for income tax cuts to the wealthy but no increase in Newstart or abolishing robo-debts. After 18 May, Australia will hurtle faster towards our own silent spring: more Murray-Darling fish kills; more kaleidoscopic colours bleached from our battered reefs; more droughts, floods, fires and storms flattening crops, animals, humans.

Some Australians know this keenly, achingly, heart-breakingly. Many of us do not or will not know it. Many vulnerable Australians who stood to gain from Labor’s promised redistribution refused to hope or trust their fellow citizens and our broken democracy, voting with fear, anger and hatred to retain what little they had.

What should we do in this apocalypse?

Shoko Yoneyama argues we can no longer rely on the nation-state, on the grand narratives and abstract science of modernity, or the promise of happiness through material consumption. She offers instead ‘new animism’, taking the reader on an amazing and delightful journey through Japanese folk stories, local Shinto traditions, the living presence of slime mould, forests and the sea in the lives, and thus the imaginations and research of her protagonists.

To experience the journey you will need to borrow or buy the book ($74 as an e-book from Dymocks, and between $120 and $240 in its beautiful hardcopy version).

Here, I will focus on the implications of forging our animistic connections in a world deformed by disasters like Minamata and Fukushima. Where preindustrial animism was the taken-for-granted connection with the world, ‘new animism’ requires hard work by the self and is constructed in tension with post-industrial society. Self does the thinking and questioning which achieves the interconnectedness of three central concepts: life, nature and soul (p213). Connection is key: Ogata talks of moyai, mooring boats together (p14). Nature is around us, and also within us. The visible natural world is ‘a manifestation of the vitalistic force behind nature … life itself is a collective entity where there is no distinction between human and nonhuman, the animate and the inanimate’ (p212). Beyond our science-based understanding of ‘sustainable development’ or ‘interconnected ecosystems’ animism asserts the need for spiritual sustenance supporting our endeavours.

Further, because of the understanding that ‘the project of modernity is ill-conceived and dangerously performed’ (p18), new animism has a moral imperative. It requires us to learn ‘respectful relationships with other persons’, ‘not all of whom are humans’ (Graham Harvey, cited pp18-19).

The Minamata disease was caused by methyl-mercury effluent from the Chisso chemical factory, pouring untreated into Minamata Bay, disrupting the neurological pathways of first the fish, then the cats who ate the fish bones, and then the fishermen and their families in the nearby villages (p4-5). Ogata Masato was initially committed to seeking compensation from Chisso for killing his family. Gradually, he came to realise that compensation is all about money, and silencing the victims, and that Chisso and the government had no care for the sufferers (p45-7).

In a period of madness, Ogata finds the ‘Chisso within’ himself. He is part of the human world which is causing ecological crisis; he is consuming goods made from chemical factories; he might have a very different perspective had he been a Chisso employee (p48-53,186). Ogata relinquished his long-held grudge against Chisso, and now understood the responsibility of humans towards other living things: ‘compensation does not mean anything to the sea. It means nothing to fish or cats’ (p53). He recognises the tsumi (sin) he carries and must ‘apologise at the level of the soul’ for what humans have done, thus finding ‘the salvation of his soul’ (p61). This means also meeting the souls of the deceased in dialogue, meeting other people without prejudice to convey the legacy of Minamata, connecting with future generations by keeping the embers of Minamata alive and regaining connectedness with the soul or life-world lost in modernity (p65).

The villagers continued to eat the local fish even when the causal link with their strange disease was suspected. They continued to have children, even to grow up deformed, calling them ‘takara-go’ (treasure child) because they ‘placed complete faith in life and received it with reverence and gratitude’. ‘Ebisu, the god of the sea, was sharing this bounty’ with them (p55). The deity Ebisu is the ‘leech child’ of two kami, set adrift by those kami because deformed (limbless). Ebisu was found and cared for by humans and he reciprocated as the god of bountiful fortune in fishing and business (p56).

Yoneyama explores Miyazaki Hayao’s philosophy through his manga (comic) version of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind¸ released two years ahead of the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster. The manga depicts ‘a post-apocalyptic future world’ created by a nuclear war 1000 years earlier (pp161-2). Through Nausicaä’s interactions with giant insects (Ohmu), the Sea of Corruption (a deadly toxic forest) and the gigantic Slime Mould (p184), Miyazaki refutes the dualism between good and evil (Nausicaä herself has darkness inside her) and between nature and human design. For example, Nausicaä has the opportunity to choose salvation through technology but rejects it because this promise of a ‘pure’ life comes only by ‘killing all (polluted) life’ (p190). Ultimately, Nausicaä’s ‘oneness with nature’ enables her ‘to bring peace to the human world, even though it is a polluted world and even though the humans might still perish in the end’ (p185).

Miyazaki’s father built his wealth from the munitions industry and Miyazaki’s first memories are of escaping the fire-bombing of Tokyo (p169-179). As an ‘emotional leftist’, Miyazaki rejected his parents’ ‘mistakes’ and hated adults who boasted of ‘stabbing Chinese people to death’ (p179,170), a rejection that severed any connection with Japan. Miyazaki finds the animism which connects him with his country ‘deep inside his heart, or soul’ which embraces ‘a pure place … where people are not to enter’ (p180). He finds a ‘connectedness with nature, self, and ancestors’ (p179). Although non-human creatures carry ‘on their shoulders the sin humans have caused’ (p162), ‘the world is worth living in’ (p172) and ‘we must live’, the tagline of both Nausicaä and The Wind Rises (p164).

We are also compromised by the ‘sins’ of materialism. Our laptops ‘must have used nuclear-power-generated electricity at some stage in their conceptualisation, manufacturing, marketing, sales or transportation. … (W)e are all responsible … for the random genetic mutations amongst the tiny pale-grass-blue butterflies caused by the nuclear accident in Fukushima’ (p216).

Both ‘life-world’ and ‘system society’ (as Ogata describes contemporary post-industrial society) are, like two feet, indispensable for walking and we must learn to live with the dialogue between them (p70,73), although ‘our pivotal foot should be in the life world’ (p216). Yoneyama calls on us to join like star sands the hotspots of thinking about animism, in our own unique ‘mandala-like space’, based on our own ‘fabric of relations’, our own grassroots locality and the whisperings, or kehai (hint of a movement) of ‘something out there’. Openness to the invisible and spiritual can reveal to us, perhaps only briefly, how beings of all kinds bring one another into existence (p221,225)

In this necessarily deformed world, hope comes from the elm trees which were affected by abnormally hot weather one year but recovered the subsequent year which was just as hot, through ‘connecting to their ancient memories’, according to Miyazaki (p197).

Hope comes from the revival of the Deer Dance when the drums which perform it are miraculously found in the rubble of the Fukushima disaster. Hope comes from the tiny undamaged shrines dotted along the ‘tsunami line’ where the water divided and the tsunami ran out.

Instead of the government’s giant concrete seawall as a retort to future tsunamis, hope for the villagers and townspeople comes from building a living wall of tsunami debris topped by a Sacred Forest grown from local seeds and nuts (p232-236).

Hope does not come from election outcomes. As Yoneyama notes, the massive anti-nuclear actions and demonstrations and their slogans of ‘life is more important than money!’ did not translate into the ousting of the nationalistic bellicose Abe government (p2) or prevent the re-opening of nuclear reactors.

New animism recommends we breathe in the kehai, taking from it sustenance and meaning, and find our own local grassroots paths to connection and action, growing more effective as joining with others like star sands.

Header photo: Murray cod, January 2019 by Barbara Pocock

Text photo: Nausicaä cover

[Opinions expressed are those of the author and not official policy of Greens WA]

See

discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/337797153

Article in Anthropological Notebooks ·

December 2019

![]()

CITATIONS READS

0

217

1

author:

Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History

Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History

120 PUBLICATIONS 916 CITATIONS

Some of the

authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

![]() Ainu,

Okhotsk and hunter-gatherers in north Japan View project

Ainu,

Okhotsk and hunter-gatherers in north Japan View project

Millet

and beans, language and genes. The dispersal of the Transeurasian languages View project

All

content following this page was uploaded by Mark J. Hudson on 06 December 2019.

The user has

requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Book reviews

![]()

Yoneyama, Shoko. 2019.

Animism in Contemporary Japan: Voices for

the Anthropocene from Post-Fukushima Japan. Abingdon: Routledge. xi + 250

pp. Hb.: £115.00.

ISBN: 9781138228030;

Ebook.: £20.00. ISBN: 9781315393902.

From the mid-1950s, people living in

fishing villages around Minamata in western Japan began dying terrible deaths

from mercury poisoning traced to wastewater from a factory in the town.

Thousands of people remain affected by one of the world’s worst criminal cases

of industrial pollution. The Minamata incident provides the starting point for

this new book by sociologist Shoko Yoneyama. Given that another awful case of

pollution began at Fukushima in March 2011, how are we to understand and

respond to such horrors? This book analyses four Japanese intellectuals, three

of whom have been directly involved with Minamata. In all four cases, the

author Yoneyama argues that “animism” has formed the basis of their responses

to Minamata and other crises of modernity.

This volume is published in Routledge’s Contemporary Japan Series, but the

author insists that her aim is not to ‘describe Japanese culture by using the

notion of animism or anything else for that matter’ (p. 24). Instead, Yoneyama

aims to focus on what she terms the “grassroots animism” of four individuals

who happen to be Japanese. We will discuss below whether Yoneyama succeeds in

this objective of escaping the overdetermined space (aka ideology) of Japanese

animism, but it will be useful to begin this review by attempting to explain

the significance of her approach. For many readers in Japanese Studies, the

term “animism” will immediately bring to mind the reactionary atavistic

writings of philosopher Takeshi Umehara (1925-2019), the first director of the

International Research Center for Japanese Studies (an institution known

colloquially as the Nichibunken).

From the 1980s, Umehara began to propound a vision of Japanese culture based on

deep animist roots. This vision was taken up by several of Umehara’s former

associates at the Nichibunken, especially Yoshinori Yasuda. In her

Introduction, Yoneyama (pp. 20-22) provides a short but incisive critique of

the writings of this group, which we might call the Alt-Nichibunken. Umehara’s animism was effectively an attempt at

building a ‘State Animism’. Even though Umehara himself was critical of the

appropriation of Japan’s cultural traditions by State Shinto in the late 19th

and early 20th centuries, his response was to create the

fantasy of a homogenous “forest civilisation” closely linked to the Japanese

state and emperor. In this book, Yoneyama attempts to distance herself from this

view of animism as nationalist discourse; in fact, she chooses to analyse the

writings of four individuals who have taken “intellectual journeys” which have

positioned themselves ‘the furthest away one can get from presenting a national

discourse’ (p. 22).

The four substantive chapters of the volume discuss the

work of Masato Ogata (b. 1953), a fisherman, activist and writer in Minamata;

Michiko Ishimure (1927-2018), a writer best known for her Paradise in the Sea of Sorrow: Our Minamata Disease; sociologist

Kazuko Tsurumi (1918-2006); and film director Hayao Miyazaki (b. 1941). These

are all significant figures in post-war Japanese letters but do they, in fact,

share an animist worldview? As discussed below, Ogata’s view of the world could

certainly be called ecological, but

Yoneyama notes that he does not use the word “animism” (p. 54). Similarly,

Ishimure rarely refers to animism, though Yoneyama stresses that ‘an animistic

theme runs

189

Anthropological Notebooks,

XXV/1, 2019

![]()

through her literary work’ (p. 81).

In contrast to Ogata and Ishimure, Miyazaki identifies his artistic philosophy

as influenced by animism, although he denies its religious nature, saying ‘I do

like animism. I can understand the idea of ascribing character to stones and

wind. But I don’t want to laud it as a religion’ (p. 180). Of the four

individuals discussed here, it is the academic Tsurumi who was most explicit

about her attempts to recover animism as a ‘disappearing “way of knowing” that [she] discovered in Minamata’ (p. 143) and to

use that animism to build a new type of social science. The animism discussed

in Yoneyama’s book is, as the author herself admits (p. 223), not a religion (however one defines

that) and rarely involves any rituals, although Ogata (p. 56) mentions several

customs performed by fishermen in Minamata. Rather than “religion”, Yoneyama

offers the term “postmodern animism”, defined as a ‘philosophy of the

life-world’ (p. 224). Suddenly, “animism in contemporary Japan” looks more like

an extension of phenomenology and the Romantic concern with the environment as

a world of experience.

What, then, if not animism? My view is that

analysing the four individuals in terms of ecology

would have been more interesting and might have brought their ideas further

away from the virally reproduced aura of Japanese Nature. The four individuals

possess rather different views on nature and ecology, although all share the

Romantic idea of the environment as a life-world that can transform self and society.

Kazuko Tsurumi has by far the most academic take of the four, discovering

animism in the beliefs of people in Minamata and being herself ‘spiritually

awakened’ (p. 116) to its potential in developing a critique of modernity.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of Tsurumi’s work to appear in this volume

is her discussion of the ecologist Kumagusu Minakata (1867-1941). Minakata’s

work on slime moulds has potential to link with recent debates in environmental

philosophy—such as Timothy Morton’s writings on queer ecology and the “strange

stranger”—yet both Tsurumi and Yoneyama limit themselves to connections with

esoteric Buddhism and animism.

Hayao Miyazaki’s interest in nature began with him

reading Sasuke Nakao’s “broadleaf evergreen forest hypothesis”, first published

in 1966. This theory, which links western Japan with south China and Southeast

Asia in an Austrian ethnology-inspired Kulturkreis,

provided Miyazaki with a liberating means to understand that Japan ‘was

actually connected to the wider world beyond borders and ethnic groups’ (p.

177). As well as an escape from nationalism, the theory also stimulated

Miyazaki to ‘believe that greenery was beautiful’, in stark contrast to his

younger days when he ‘thought that greenery was nothing but a symbol of

poverty’ (p. 179). As a result, Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli attempts to

incorporate aspects of the landscape including ‘weather, time, rays of light,

plants, water, and wind’ in its films (p. 176). Miyazaki’s comment that, ‘Human

relationships are not the only thing that is interesting’ checks one of

Lawrence Buell’s boxes for classification as an environmental text, but his

overall approach seems to limit the environment to “greenery”, implying that,

say, the depicted urban landscapes or the un-depicted

train journeys in Yasujirō’s Ozu’s film Tokyo

Story do not equally constitute environment. One critic has said that

‘Miyazaki has “baptized a whole generation” with an animistic imagination’ (p.

159), but in what way is Totoro more animistic than Winnie the Pooh—except that

the former is portrayed within a Japanese context that invites

190

Book reviews

![]()

cultural readings associated with animism

and folk Shinto?

Michiko Ishimure is well known as one of Japan’s foremost

environmental writers, and her work has been much discussed within

ecocriticism. Ishimure’s writings sometimes assign “personhood to nonhumans”

including “crow-women” and yamawaros

mountain spirits (pp. 82-84). The discussion here in Chapter 2 is unclear as to

how Ishimure perceived the relations between human and nonhuman persons.

Certain passages from her writings reproduced here suggest that nonhuman

persons inhabited another world deep in the mountains and dark forests.

Elsewhere, Ishimure claims that in the ‘pre-pollution era of the Shiranui Sea,

people, nature (including animals), and kami

coexisted closely and intermingled with each other’ (p. 83). The trajectory is

from living in the world to thinking about the world (p. 93), the implication

being that ecological relations only existed in a stage prior to modernity.

With his anxieties over consumerism, Masato Ogata is

perhaps the most ecological of the four thinkers discussed here. Throwing his

television out of his door into the front garden (‘You beast! How dare you

break into my house and order us around. Go there! Buy this!’ [p. 49]), Ogata

understands the close link between consumerism and ecology. Ogata’s book Chisso wa watashi de atta [‘I was

Chisso’] should be an essential text for the Anthropocene, encapsulating so

beautifully as it does the irony of the sudden realisation that it is we who

have been destroying the world all along.

Other readers will no doubt have different takes on the

ecology of the four people discussed in this volume, but my point is that

thinking about their differences tell us a great deal about views of the

environment in post-war Japan. By contrast, forcing all four into a box

labelled ‘animism’ misses much that is interesting. Animism in Contemporary Japan succeeds in breaking and entering the

‘State Animism’ of the Alt-Nichibunken, but in my view, it is unable to achieve

two of its objectives: escaping the dark star pull of Japanese culture and

changing the world.

Let us take Japanese culture first. Yoneyama insists that

her aim is not to critique the West or to develop binary East/West oppositions

of the type found in the works of Umehara and Yasuda. The book indeed adopts a

very different tone from the virulently anti-Western/anti-Christian tracts of

Yasuda in particular (cf. the quote on p. 21 of this volume). However, ‘the

West’ is primarily noticeable here by its absence; there is almost no

discussion of how the animism of the four individuals might resonate with

spiritual ideas beyond Japan. A rare exception is a brief mention of Saint

Francis of Assisi who Yoneyama mistakenly describes as a ‘medieval heretic’ (p.

24)—although his ideas may have been unusual for his time, he would hardly have

been canonised had he been a heretic! In assuming that the diverse writings and

ideas analysed here can be glossed as ‘animism in Japan’, Yoneyama plays down

the political functions of that phenomenon. Grassroots animism, like folk

Shinto, is assumed to be egalitarian and apolitical. For example, in Table 3.2

(p. 130), the “Ideological function” of folk Shinto is listed as “Irrelevant”.

Such characterisations seem to me to overlook the agency of individuals

participating in the social lives of local communities and local spirits. The

work of anthropologist Rane Willerslev, for example, shows how Yukaghir hunters

in Siberia regard animism as an ideology to be argued with and negotiated

within.

191

Anthropological Notebooks,

XXV/1, 2019

![]()

What, then, about changing the world? Like many

before her, Yoneyama seems to believe that Japan’s unusual place within

modernity gives the country a unique role in responding to the crises of that

same modern system. Yoneyama claims that, ‘the extent to which Japan has “never

been modern” is greater than that of the advanced societies in the West’ (p.

4). Similarly, for Antonio Negri, ‘Japan’s powerful cultural traditions which

manage to co-exist with super-modernity have the potential to solve [the] conundrum’

of ‘finding a new way to coexist with nature’ (p. 205). That Japan’s amalgam of

old and new provides a privileged position from which to build a new world

order was exactly the point made by Umehara. Changing the world has always been

the holy grail of what Timothy Morton calls the “religious style” of being

ecological, but the grassroots animism of Japan—however important to those people at the level of the grassroots—is

unlikely to find a broader resonance without a fundamental reframing of its

terms of reference.

By now, it will be clear that I find this book’s use of

animism as a way of encapsulating the diverse and fascinating ideas discussed

here as rather unconvincing. A sociological analysis of animism as a response

to power or a focus on ecology (or environmental philosophy) would, in my view,

have given the book a wider appeal. Despite this reservation, however, I found Animism in Contemporary Japan to be a

stimulating and well-written work which provides a wonderful way to think

through many important issues about ecology, society and contemporary Japan.

The arguments of the volume resonate strongly with several key Anthropocene

debates, especially those about responsibility, poetics, and civil society. I

hope this book will be widely read and debated, both within Japanese Studies

and beyond.

MARK J. HUDSON

Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History (Germany)

Animism in contemporary Japan : voices for the Anthropocene from post-Fukushima Japan

Yoneyama, Shoko, editor.; 2018

Routledge contemporary Japan series ; 77.

COURSE

Send to

View Online

Full text availability

Taylor & Francis eBooks Complete

Available to University of Adelaide Staff and Students.

Walk in user access permitted.

Access is available for Unlimited simultaneous users

----

Title

Animism in contemporary Japan : voices for the Anthropocene from post-Fukushima Japan

Contributor(s)

Yoneyama, Shoko, editor.

Series

Routledge contemporary Japan series ; 77.

Subjects

Animism -- Japan -- Fukushima

Electronic books

Identifier(s)

ISBN : 1-315-39390-5

ISBN : 1-315-39389-1

ISBN : 1-138-22803-6

Creation Date

2018

Description

'Postmodern animism' first emerged in grassroots Japan in the aftermath of mercury poisoning in Minamata and the nuclear meltdown in Fukushima. Fusing critiques of modernity with intangible cultural heritages, it represents a philosophy of the life-world, where nature is a manifestation of a dynamic life force where all life is interconnected. This new animism, it is argued, could inspire a fundamental rethink of the human-nature relationship. The book explores this notion of animism through the lens of four prominent figures in Japan: animation film director Miyazaki Hayao, sociologist Tsurumi Kazuko, writer Ishimure Michiko, and Minamata fisherman-philosopher Ogata Masato. Taking a biographical approach, it illustrates how these individuals moved towards the conclusion that animism can help humanity survive modernity. It contributes to the Anthropocene discourse from a transcultural and transdisciplinary perspective, thus addressing themes of nature and spirituality, whilst also engaging with arguments from mainstream social sciences. Presenting a new perspective for a post-anthropocentric paradigm, Animism in Contemporary Japan will be useful to students and scholars of sociology, anthropology, philosophy and Japanese Studies.

===

Contents

Cover; Half Title; Series Page;

Title Page; Copyright Page; Dedication;

Table of Contents; List of illustrations; Acknowledgements; Notes on Style;

INTRODUCTION

A theoretical map: Reflections from post-Fukushima Japan; Silent springs; The Anthropocene and the enchantment of modernity; World-risk-society Japan; Spirituality as a foundation for environmental ethics; Spirituality: A lacuna in social science; Minamata and Fukushima in Japan's modern history; Connectedness as a legacy of Japan's modernity; Minamata as method; Framing animism

Discourse on animism in Japan

1: Japanological discoursePositioning 'Japan'; Discourse on animism in Japan

2: Grassroots discourse; Life stories as method; The 'data' and the structure of the book; Notes;

PART I: Animism as a grassroots response to a socio-ecological disaster;

1. Life-world: A critique of modernity by Minamata fisherman Ogata Masato; A grassroots philosopher; The price of life; If not money, what?; A journey to the life-world; The development of the concept of the life-world; Where do you put your soul? The life-world or the system society?

Postmodern animism and the lacuna of social scienceNotes;

2. Stories of soul: Animistic cosmology by Ishimure Michiko; A grassroots writer; An animistic world to pine for; The Ishimure Michiko phenomenon; 'You don't have a soul, perhaps?'; The fall of paternalistic authority; The 'ancestor of grass' as a story for change; Notes; PART II: Inspiring modernity with animism;

3. Animism for the sociological imagination: The theory of endogenous development by Tsurumi Kazuko; In pursuit of a paradigm change; Transcultural creativity; Minamata encounter

Tsurumi Kazuko in the trajectory of social scientific thinkingTheory of endogenous development; Animism and Shinto; Animacy as the source of life and movement; Slime mould: Connecting esoteric Buddhism, science, and animism; The question of self; A sociological discourse on animism; Notes;

4. Animating the life-world: Animism by film director Miyazaki Hayao; Animism for the global audience; The spirit of the times; Post-Fukushima Japan: Another beginning, another ending; War as the beginning; Transforming negativity

1: Connecting with the soul of children

Transforming negativity

2: Reconciling with Japan through natureWhy animism?; Beyond dualism: 'Life is light that shines in the darkness'; Into a deeper realm of animism: Ohmu and Slime Mould; Injecting soul through animation; Embodying animism; Notes;

CONCLUSION Postmodern animism for a new modernity; Intangible cultural heritage; Postmodern animism; Three challenges for the social sciences; Postmodern animism is a philosophy of the life-world; Notes;

Epilogue: The re-enchanted world of post-Fukushima Japan; Folk festivals; Shrines as tsunami markers;

The Sacred Forests Project;

Notes; Index

Related titles

Available in other form: Link to related record

Publisher

New York : Routledge

Format

1 online resource (250 pages).

Language

English

Course Information

4210_ASIA_3007: Asia Beyond Climate Change; Asian Studies; Shoko Yoneyama

Some readings from the same Course