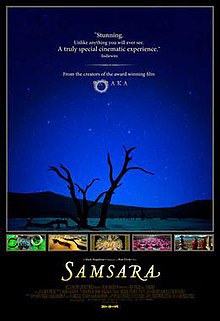

Samsara (2011 film)

| Samsara | |

|---|---|

Film poster | |

| Directed by | Ron Fricke |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by | Mark Magidson |

| Cinematography | Ron Fricke |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by |

|

Production company | Magidson Films |

| Distributed by | Oscilloscope Laboratories |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 102 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Budget | $4 million[1] |

| Box office | $6 million[1] |

Samsara is a 2011 American non-narrative documentary film of international imagery directed by Ron Fricke and produced by Mark Magidson, who also collaborated on Baraka (1992), a film of a similar vein, and Chronos (1985).

Completed over a period of five years in 25 countries around the world, it was shot in 70 mm format and output to digital format. The film premiered at the 2011 Toronto International Film Festival and received a limited release in August 2012.

Synopsis[edit]

The official website describes, "Expanding on the themes they developed in Baraka (1992) and Chronos (1985), Samsara explores the wonders of our world from the mundane to the miraculous, looking into the unfathomable reaches of humanity's spirituality and the human experience. Neither a traditional documentary nor a travelogue, Samsara takes the form of a nonverbal, guided meditation."[2]

Production[edit]

Samsara is directed by Ron Fricke and produced by Mark Magidson. The pair had collaborated on Baraka (1992) and reunited in 2006 to plan Samsara. They researched locations that would fit the conceptual imagery of saṃsāra, to them "meaning 'birth, death and rebirth' or 'impermanence'". They gathered research from people's works and photo books as well as the Internet and YouTube, resources not available at the time of planning Baraka.[3] They considered using digital cameras but decided to film in 70 mm instead, considering its quality superior.[4] Fricke and Magidson began filming Samsara the following year.[5] Filming lasted for more than four years and took place in 25 countries across five continents.[6] Three years into filming, the pair began assembling the film and editing it. They pursued several pick-up shoots to augment the final product.[3]

The crew used three 70 mm cameras for filming; two cameras manufactured by Panavision and one specialty time-lapse camera designed by Fricke. While the scenes were captured on 65 mm negative film, they were output to Digital Cinema Package (DCP), a digital output. Magidson described the process, "We're doing a combination of what we think is the best of both technologies, the best way to image capture and then the best way to output. Once we get into the digital environment, we're able to refine the imagery, we're able to save shots that we'd have to otherwise trash really for various reasons." Where they cut their negatives for Baraka, the negatives for Samsara were scanned then worked on digitally. The pair used the Telecine process to format the film to ProRes for the editing process and used Final Cut for editing.[3]

The crew shot from a bird's-eye view a scene of pilgrims surrounding the Kaaba in Mecca, Saudi Arabia. A 40-floor building was recently constructed next to the mosque that surrounded the Kaaba, so the filmmakers were able to film the pilgrims with permission of the building's owner.[3]

Music[edit]

The score was composed by Michael Stearns, Lisa Gerrard and Marcello De Francisci. Stearns previously collaborated with the filmmakers on Baraka and Chronos, and Gerrard on Baraka. Unlike Baraka, Samsara was edited without music, and the composers worked on numerous sequences as separate pieces, before connecting. Magidson explained of the pieces, "It's a piece of music you can listen to as music as well that interprets their feelings to know that imagery in that sequence visually, so they're kind of interpreting it musically." The scoring process lasted between six and seven months.[3]

Filming locations[edit]

Samsara was filmed in nearly one hundred locations across 25 countries over the course of exactly five years. Some locations include: Angola, Brazil, China, Denmark, Egypt, Ethiopia, France, Ghana, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Israel/Palestine, Italy, Japan, Mali, Myanmar, Namibia, Philippines, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, Thailand, Turkey, United Arab Emirates and United States.[7]

- Great Mosque of Djenné

- Dogon Village, Bandiagara Escarpment

- Cliff Dwellings near Terelli

- Tagou Martial Arts School, Zhengzhou

- Shanghai

- Changchun City, Jilin Province

- Zhangzhou City, Fujian Province

- Beijing (1000 Hands Dance)

- Lan Kwai Fong Hotel

- Tri Pusaka Sakti Art Foundation

- Kawah Ijen Sulfur Mine, East Java

Israel and Palestinian Territories

- Nablus Checkpoint, Nablus

- Bethlehem

- Dome of the Rock, East Jerusalem

- Church of the Redeemer, East Jerusalem

- Western Wall, East Jerusalem

- Lotte Kasai driving range, Chiba

- YK Tsuchiya Shokai Doll Factory, Tokyo

- Osaka University

- Atri, Kyoto

- Fushimi Inari Shrine, Kyoto

- Toshimaen/Hydropolis, Tokyo

- Yoyogi Park, Tokyo

- Orient Kogyo Showroom, Tokyo

- Advanced Telecommunications Research Institute International ATR, Tokyo

- Bagan, Mandalay

- Mount Popa, Popa Taungkalat Monastery

- Mingun Pahtodawgyi

- Cebu Provincial Detention and Rehabilitation Center (CPDRC Dancing Inmates), Cebu City

- Payatas Trash Dump, Quezon City

- Arms Corporation of the Philippines

- Manila Streets

- Demilitarized zone, Panmunjom

- Hyundai Glovis, Co. Ltd Shipyards, Seoul

- Cascade Go-Go Bar, Nana Plaza, Bangkok

- Siriraj Medical Museum, Bangkok

- Moesgård Museum

- Silkeborg Museum

- Mariesminde Poultry Farm

- Bøgely Svineproduktion

- Château de Versailles

- La Sainte-Chapelle, Paris

- Mont-Saint-Michel

- Cathedral Notre-Dame de Paris, Paris

- Cathedral Notre Dame de Reims

- Paris Métro

- Mont Blanc

- Aiguille du Midi

- Olivier de Sagazan, Paris

- Mont Blanc

- Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II, Milan

- Teatro alla Scala, Milan

- Catacombe dei Cappuccini, Palermo

- St. Peter's Basilica, Vatican City

- Divino Salvador Church, São Paulo

- Sé Metro Station, São Paulo

- Paraisópolis favela, São Paulo

Themes[edit]

Fricke and Magidson emphasized avoiding a particular political view in assembling the film. Fricke said, "We just try to keep it in the middle and then we form little blocks of content and then we set them aside until we have enough. We did all of this without music or sound effects. We just let the image guide the flow and then we started stringing the blocks together."[3] Nicolas Rapold of The New York Times wrote that Samsara's lack of a specific message is "a departure from similarly expansive, globally conscious nonfiction films in vogue now, like the critically acclaimed work of Michael Glawogger ('Workingman's Death,' which depicts the same sulfur mines as 'Samsara') and Nikolaus Geyrhalter ('Abendland') that also serve as probing sociological critique."[8]

Release[edit]

Box office[edit]

Samsara premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival in September 2011. In March 2012, Oscilloscope Laboratories acquired the rights to distribute Samsara in the United States.[6] The film had a limited release in two theaters on August 24, 2012. By its fifth weekend (September 14–16), Samsara had expanded to 60 theaters and achieved the highest-grossing documentary release of 2012.[9] On October 14, distributor Oscilloscope Laboratories announced that at $1.8 million in box office earnings, Samsara had become the highest-grossing film in Oscilloscope's (relatively short) history.[10]

Critical reception[edit]

Rotten Tomatoes gives the film a score of 76% based on reviews from 79 critics and reports a rating average of 7.00/10. It reports the critics' consensus that "it's a tad heavy-handed in its message, but Samsara's overwhelmingly beautiful visuals more than compensate for any narrative flaws."[11] At Metacritic, which assigns a weighted average score out of 100 to reviews from mainstream critics, the film received an average score of 65% based on 23 reviews, reflecting "generally favorable reviews."[12]

Kenneth Turan, reviewing for the Los Angeles Times, called Samsara "as frustrating as it is beautiful." Turan expressed frustration that the filmmakers did not name the more obscure locations, such as the Cebu Provincial Detention and Rehabilitation Center in the Philippines. The critic also took issue with some of the film's "disconcerting" images. Turan concluded, "Some of the connections made are too obvious, like following images of ammunition with a portrait of a severely wounded veteran, while others are completely elusive. Shots of the devastation Katrina left behind in New Orleans are beautifully spooky, but does it say anything useful to follow that with images of Versailles? The makers of 'Samsara' want to free our minds, but their technique makes us their prisoners more often than not."[13]

In the Chicago Sun-Times, Roger Ebert awarded Samsara a full four stars, writing that it provided "an uplifting experience" through its use "of powerful images, most magnificent, some shocking, all photographed with great care in the highest possible HD resolution." Ebert extolled the film's capturing of images of what may eventually be lost to humanity and noted that there were also images that could reflect the reason for these losses.[14][15] Katie Walsh, writing for indieWire's The Playlist, applauded Samsara's "technical achievements" and noted that the film used the "intellectual montage" technique. Walsh said the film was similar to Man with a Movie Camera, but took "the idea to new global and spiritual heights." She said of the film's entirety, "While one can discuss the technical prowess of these shocking and beautiful images, it doesn't do justice to the spiritual cinematic power of this work."[16]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b "Samsara (2012) - Financial Information". The Numbers. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ^ "About Samsara". barakasamsara.com. Retrieved September 11, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Douglas, Edward (August 21, 2012). "Interview: The Filmmakers Behind Samsara". ComingSoon.net. Retrieved September 11, 2012.

- ^ Rapold, Nicolas (August 17, 2012). "Planetary Poetry, Woven Into a Movie". The New York Times.

- ^ Hayes, Dade (May 18, 2007). "Fricke directs 'Baraka' sequel". Variety.

- ^ a b McNary, Dave (March 14, 2012). "Oscilloscope Labs nabs doc 'Samsara'". Variety.

- ^ "Filming Locations for Samsara". barakasamsara.com. Retrieved January 28, 2013.

- ^ Rapold, Nicolas. "Planetary Poetry, Women into a Movie: 'Samsara,' Ron Fricke's Cinematic Portrait of the Globe." New York Times. NYTimes.com, 17 Aug. 2012. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/08/19/movies/samsara-ron-frickes-cinematic-portrait-of-the-globe.html

- ^ "Specialty Box Office: 'Sleepwalk,' 'Samsara' Among Year's Best Indie Debuts; 'Obama's America' Soars To Overall Top 10". IndieWire. 26 August 2012. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ "HIT DOCUMENTARY SAMSARA BECOMES OSCILLOSCOPE'S HIGHEST-GROSSING FILM EVER THEATRICALLY". Oscilloscope Laboratories. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ "Samsara". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ "Samsara Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (August 30, 2012). "Review: 'Samsara' is a frustrating beauty". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (September 5, 2012). "Samsara". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on August 11, 2016.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (September 5, 2012). "A trance about the planet where we live". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Walsh, Katie (August 22, 2012). "Review: 'Samsara' Tells The Story Of Our World With Stunning Visuals & Spiritual Heft". The Playlist. indieWire. Retrieved October 1, 2012.

External links[edit]

- 2011 films

- 2011 documentary films

- American documentary films

- Documentary films about spirituality

- Films directed by Ron Fricke

- Films without speech

- Non-narrative films

- Films scored by Michael Stearns

- Documentary films about India

- Films shot in Ladakh

- Films shot in Reims

- 2010s American films

- Films scored by Lisa Gerrard