악

악(惡, 영어: evil, badness)은 도덕적, 또는 종교적 관점에서 부정적인 것을 가리킨다. 옳지 못한, 이기적인 행동을 의미하여 ‘죄’와 유사한 의미로 쓰이기도 한다. 악은 착하고 올바르며 헌신적인 선(善)과 대비된다.

선천적인 악[편집]

유교와 도교에서는 인간의 선과 악이 타고난 것이라는 관점에서 성선설(性善說)과 성악설(性惡說)을 주장하기도 하였다.

영어 표현[편집]

영어로서 악은 Evil로 표현되며, 악의 혼령인 악령은 Demon이다. 악령의 가시적인 형태인 악마는 Devil로 표현된다.

같이 보기[편집]

악

악 은 일반적인 의미에서 선의 반대 또는 부족이다. 매우 넓은 개념일 수도 있지만, 일상적인 사용법에서는 보다 좁은 범위에서 깊은 사악함을 표현하는 경우가 많다. 그것은 일반적으로 여러 가지 가능한 형태를 취하는 것으로 간주됩니다. 예를 들어, 악과 일반적으로 연관된 개인 도덕적 악 또는 비 개인적 자연 악 (자연 재해 또는 질병의 경우와 같이)의 형태 또는 종교적 사상에서는 악마적 또는 초자연 적 / 영원한 형태 등이다 [1] .

악은 심각한 부도덕을 의미하기도 하지만 [2] , 일반적으로는 인간의 상태를 이해하는데 어떠한 근거가 없는 것은 아니고, 거기서는 싸움 이나 고통 (cf. 힌두교 )이 악 의 진정한 근원이다. 한 종교적 맥락에서 악은 초자연적 인 힘으로 표현되었습니다 [2] . 악의 정의는 다양하고 동기의 분석도 다양하다 [3] . 개인적인 악의 형태와 일반적으로 관련된 요소는 분노 , 복수 , 공포 , 증오 , 심리적 외상 , 편의주의, 이기주의 , 무지 , 파괴 또는 무시 를 포함한 불균형 행동을 포함한다 [4] ] .

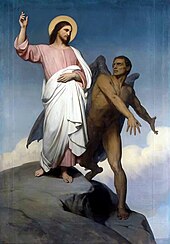

악은 선과 는 반대의 이원적 적대적 이원론 으로 인식될 수 있다 [5] . 그렇다면 선이 이기고 악은 이길 수 있다고 여겨진다 [6] . 불교 의 정신적 영향력을 가진 문화에서는 선과 악이 모두 대립적인 이면성의 일부로 인식되고 있으며, 그 자체는 성불에 의해 극복되어야 하는 것으로 여겨진다[ 6] . 선과 악에 대한 철학적 문제는 선과 악의 성격에 관한 메타 윤리학 , 어떻게 행동해야하는지에 대한 규범 윤리학 , 특정 도덕적 문제에 대한 응용 윤리학 의 세 가지 주요 연구 영역에 포함됩니다. 이다 [7] . 이 용어는 행위 주체를 수반하지 않는 사건이나 상황에 적용되지만,이 기사에서 다루는 악의 형태는 악인 또는 그 실행자를 가정합니다.

종교나 철학 중에는 인간을 기술할 때 악의 존재나 유용성을 부정하는 것도 있다.

일본어의 「악」[ 편집 ]

일본어에 있어서의 「악」이라고 하는 말은, 원래 면도와 힘을 나타내는 표현으로서도 사용되고, 부정적인 의미밖에 없는 것은 아니다. 예를 들면, 겐요사키 의 장남 요시 헤이 는 그 용맹함으로부터 「악원태」라고, 좌대신 후지와라 요시나가 는 그 타협을 모르는 성격으로부터 「악좌부」, 에도 시대 초기에 권세를 흔든 이심 숭전 은 그 강한 정치 수법에 의해 '대욕산 기근원 가미죠지 악국사'로 평가됐다. 가마쿠라 시대 말기의 악당 도 그 전형적인 예이며 힘이 강한 세력이라는 의미이다.

본래 '악'은 '돌출했다'는 의미를 가진다. 돌출하고 평균에서 벗어난 인간은 광범위하고 지배적인 통치, 혹은 징병한 군대에 있어서의 제휴적인 행동의 방해가 되어, 이것 때문에 고대 중국에 있어서의 「악」개념은, 「명령·규칙에 따르지 않는 것」 에 대한 가치 평가가 되었다. 한편 '선'개념은 '황제의 명령·정치적 규칙에 따른 것'에 대한 가치평가이다.

「고사기」에 있어서, 「악사」는 「마카고트」라고 읽게 한다(고대의 해석에서는, 악의 훈독은 「마카・마가」가 된다). 반대로 '선사'는 '요고트'라고 읽는다. 현대에서는, 마가고트의 한자는 「연사」를 맞히고, 요고트는 「길사」의 글자를 맞추고 있는 것에서도, 고대의 감성에서는, 禍(?)=재앙=악이라고 하는 도식이 된다.

덧붙여 현재의 일본에서의 악개념은, 서구의 가치관에 가까운 것이 되고 있지만, 여전히 차이를 포함하고 있다.

선과 악 [ 편집 ]

악은 선과 대비된다.

인간이 선악을 의식, 판단하는 장면은 다양하지만, 가정에서의 밑에서 교육 , 스포츠 , 법률 등 질서를 필요로 하는 모든 장면에서 찾을 수 있다. 생활에 맞는 것으로 종교 로, 오락이나 전승으로서 이야기 위에서 다루어지는 경우도 많다. 그 때에는 선을 권유하는 악을 제외하는 것( 권선징악 ), 선과 악의 대결 등이 종종 주목된다.

선과 악은 해석이나 판단에 의해 바뀌는 경우도 있기 때문에 규범이라는 형태로 존재하는 것은 이러한 혼란을 피하기 위해 자주 사용되는 수단이다.

사회심리학 [ 편집 ]

순수악의 신화 [ 편집 ]

사회심리학자인 로이 바우마이스터는 일반인의 악에 대한 소박한 이해에 근거한 지나치게 잘못된 악의 인식을 '순수악의 신화'로 표현하고 있다[8 ] . 바우마이스터에 따르면, 순수 악의 신화에는 주로 8개의 특징이 있다.

- 악은 다른 사람을 의도적으로 손상시키는 것입니다.

- 악한 사람은 사람을 해치는 것을 즐긴다.

- 피해자는 깨끗하고 선한 사람입니다.

- 악인의 가해자는 우리와는 다른 인간

- 악인은 일관되게 악인

- 악은 사회에 혼란을 초래하는 것입니다.

- 악인의 가해자는 이기주의

- 악인의 가해자는 자제심이 떨어진다.

첫 번째 특징은 어린이 만화에서 전시 중 선전 까지 다른 사람을 해칠 것을 강조한다는 것입니다. 두 번째 특징은 실제 현실에서 거의 볼 수 없다. 피해자가 하는 설명에서는 악인이 웃고 있던, 즐거웠던 등이라고 강조되지만, 악인으로부터의 설명에서는 그러한 일이 나타나지는 않는다. 이것은 피해자가 순수 악의 신화의 영향을 받고 있다고 생각된다. 세 번째 특징도 현실에서는 거의 볼 수 없다. 실제 많은 살인 사건에서는 가해자와 피해자가 서로 도발하고, 그것이 에스컬레이트 해 나가는 것으로, 살인이 생기는 경우는 많이 보인다. 물론 선량하고 깨끗한 사람에 대한 무차별 폭력은 확실히 일어나지 만, 그것은 우리가 언론에서 얻은 정보에서 생각하는 것보다 드뭅니다. 네 번째 특징은 우리와 같은 사람들이 끔찍한 범죄를 저지른다고 생각하고 싶지 않다는 욕망을 반영합니다. 구체적으로는 나치 의 의사는 괜찮은 인간이라고는 생각되지 않고 [9] , 또, 전쟁중의 일미 양측에서 상대측은 열등 인종으로 간주하고 있었기 때문에, 상대를 악마화하는 것이 조장되었다는 분석도 있다 [10] . 게다가 아이들을 위한 만화의 악인은 기본적으로 외국어 말의 영어로 말한다 [11] . 다섯 번째 특징은 현실에서 많이 보이는 것이 아니라 예외 가능성이 높다. 영화에서도 시간이 지남에 따라 나빠진 사람은 보이지 않고 처음부터 악인이라고 여겨진다. 또, 현실에서도 스탈린 이나 히틀러 , 폴포트 등의 인물에 대해서도, 우리는 「그렇게 심하게 사악한 인간이 어떻게 그런 큰 권력을 얻었는지」라고 생각하지만, 「어떤 경험에 의해 그들은 악인이 되었다 버린 것인가」라고는 생각하지 않는다. 6번째 특징은 1번째 특징과 대체적인 것으로, 악과는 혼돈이며 평화와 조화, 그리고 안정을 상실시키거나 방해하는 것이다. 7번째와 8번째의 특징은 지금까지의 특징과는 달리, 현실에서는 확실히 그 경향이 보여 진실에 가깝지만, 과도하게 강조되고 있다고 한다.

악의 근본 원인 [ 편집 ]

많은 연구가 통합되면 악은 네 가지 (정확하게는 세 반)의 기본 원인을 포함합니다 [8] . 이들은 도구성, 자기중심성에 대한 위협, 이상주의, 사디즘 이며, 피해자의 입장에서라고 몇 가지 차이가 보인다. 전자 2개에 관해서는, 돈을 건네거나 악인의 자존심을 채우면 폭력 등을 회피할 수 있지만, 이상주의의 경우는 치는 손이 적고, 사디스트가 상대의 경우는 어쩔 수 없다.

도구성 [ 편집 ]

사악한 행위의 대부분은 나쁜 것 자체를 목적으로 한 것이 아니라 다른 목적 (금, 토지, 권력, 섹스)을 달성하기위한 단순한 수단으로 만들어졌습니다. 이 목적을 달성할 때 합법적인 수단으로 달성할 수 없는 경우에, 사람은 폭력을 행한다. 예를 들어 테러리스트 는 자신의 요구가 투표 나 법제 도를 통해 실현되지 않는다고 알고 있기 때문에 테러를 실시하고, 지식사회에서는 지능이 낮은 사람은 금이나 다른 보상을 얻는 방법이 한정되어 있다 . , 악행에 손을 염색한다. 폭력에 관한 연구자들은 폭력적인 수단이 장기적인 목표 달성에 효과적이지 않다고 논의해 왔지만, 단기적인 관점에서 폭력은 확실히 효과적이다.

도구의 폭력은 진화 전 단계의 잔존으로 간주된다 [12] . 인간을 포함한 사회적인 동물에서는 자원 분배를 둘러싼 사회적 충돌이 생겨 지배적이고 공격적인 개체인 알파오스가 많은 보상을 얻을 수 있다. 따라서 종내 공격은 사회생활에 대한 적응으로 생겼을 가능성이 있다. 그러나 인간은 문화를 발전시켜 싸움과 분쟁을 해결하는 대체의 비폭력적인 수단(돈, 법정 , 협상 , 타협 , 투표 )을 만들어 왔다. 최근 조사에서도 장기적으로는 대인폭력의 발생은 감소하고 있다. 다만, 때로는 우리는 공격성에 후퇴해 버려, 특히 문화적인 방책이 자신에게는 제대로 기능하고 있지 않다고 느끼는 사람 사이에서 공격성은 생기기 쉽다고 한다.

자기 중심성에 대한 위협 [ 편집 ]

한때 폭력 연구에 있어서는, 악인은 자존심 이 낮다는 것이 표준적인 지견이었지만, 바우마이스터가 실제로 문헌을 체크해 보면, 악인은 오히려 높은 자존심, 때로는 과도하게 높은 자존심을 가지고 있었다 [13] . 나중 연구에서도 자존심의 낮음과 공격이 연결되는 것은 확인되지 않았고, 반대로 나르시스트 가 보다 폭력적이라는 결과가 자주 얻어졌다 [14] . 나르시즘과 자존심을 분리한 경우에도 자존심의 영향은 무시할 수 있거나 자존심은 나르시즘의 효과를 높여 공격성에 기여하고 있었다.

그러나 나중의 연구에서 알게 된 것은 높은 자존심이 폭력을 일으키는 것이 아니라 자신이 가진 높은 자기상이 위협에 노출되거나 상처를 입었을 때 폭력이 생기는 것을 알았다. 즉, 타인으로부터의 비판에 반항하여 자존심의 손실을 회피하기 위한 전략으로서 공격이 이루어진다. 이것은 진화적인 기원을 가진 것으로 생각되며 실제로 알파오스에서는 도전자를 공격함으로써 자신의 지위를 지키고 있다.

이상주의 [ 편집 ]

이상주의 는 여러 측면에서 다른 근본 원인과 다르다. 우선 가해자들은 '자신들은 좋은 일을 하고 있다'는 신념에 근거하고 있다는 것이다. 실제로 좌익 과 우익 의 이상주의자들은 자신이 고귀한 목표를 갖고 폭력적인 수단이 정당화된다고 믿었다. 구체적인 예로는 중국이나 소련에 의한 공산주의 의 학살이나 나치 독일에 의한 홀로 코스트 등을 들 수 있다. 또한 이상주의는 다른 근본 원인을 숨기는 데 사용될 수 있습니다.

사디즘 [ 편집 ]

악의 근본 원인이 3개 반인 이유는 사디즘이기 때문이다. 악인이 새디스트라고 하는 것은 전술한 순수악의 신화이지만, 실제로 사디즘으로 간주되는 것이 몇개인가 보여진다. 살인범의 회고록에는 살인에 의해 기쁨을 얻었다고 하는 기술은 거의 보이지 않지만, 일부 사람은 실제로 사람을 해치는 것을 즐긴다.

이것은 상반 과정 이론에 의해 설명된다 [15] . 보통 사람을 다치게 하면 처음에는 흔들리고 강한 부정적인 반응을 일으키지만, 신체는 평형 상태를 유지하려고 하여 반동으로서 제2 과정을 작동시킨다. 이 과정은 처음에는 약하고 느리지만 반복 강도가 증가해 지배적으로 된다. 번지 점프 나 스카이 다이빙을 즐기게 되는 이유도 이것으로 설명된다. 또한, 과학적인 엄격한 연구는 아니지만, 고문 에 관한 연구가 이 이론을 지지하고 있다. 고문에서는 상대를 죽여 버리는 것으로 고문이 실패하는 경우가 있지만, 그것은 신인의 고문인보다 베테랑의 고문인이 상대를 죽이기 쉽다. 이것은 상반 과정 이론과 일치하고, 고문을 하는 것에 의한 고통이 줄어들고, 만족하는 쪽이 그것을 웃도는 것이 있다고 생각되고 있다.

또한 사디즘은 사이코 패스 와 관련이 있다고 생각된다. 사이코 패스는 공감성이 없기 때문에, 타인의 고통에 대해 공감에 의한 억제가 효과가 없다고 생각된다.

가장 가까운 원인 [ 편집 ]

악에 관한 연구에서 폭력을 유발시키는 요인은 흔한 것으로 밝혀졌다. 사회심리학자 에 따르면 비판, 모욕, 기온이 높고 미디어에서 폭력을 보는 것, 욕구 불만인 등이 사람의 공격성을 증가시키는 것으로 나타났다 . 16] [17] . 쏟아져 실제 폭력의 발생률은 놀라울 정도로 낮고, 그것은 자제심에 의한 것이라고 생각되고 있다. 사람은 다양한 것에 의해 공격적인 충동을 발생시키지만, 그에 대해 자제심을 이용하는 것으로 충동을 억제시키고 있다. 또한 인간에게는 적어도 다른 사회적 동물 이상의 자제심 능력을 가지고 있다.

이상으로부터, 많은 경우에서 악이나 폭력의 지근 원인 은, 자제심의 파탄이다. 특히, 알코올 은 대부분의 영역에서 자제심을 방해하고 [18] , 공격의 원인으로 잘 확립되어있다 [19] . 또한 격렬한 감정은 폭력적인 충동의 억제를 손상시키고, 미디어의 폭력은 마찬가지로 자제심을 약화시켜 공격성을 높인다.

바우마이스터의 견해로는 악의 4가지 근본 원인을 배제하기가 어렵기 때문에, 근근 원인의 자제심의 강화가 현실적인 것이다[ 8] .

중국의 윤리 철학 [ 편집 ]

후술하는 불교 와 마찬가지로 유교 와 도교 에는 서양사상에서 볼 수 있는 선악의 대립구조가 없지만 중국의 민간신앙에서는 뭔가 나쁜 것의 영향에 대해 자주 언급된다. 유교의 주요 관심사는 지식인이나 귀인에 걸맞는 올바른 사회적 관계·행동에 있었다. 그러므로 '악'이라는 개념은 나쁜 행동이 된다. 도교에서는 이원론 이 그 중심에 자리잡고 있음에도 불구하고 도교의 중심적인 덕에 대립하는 배려, 절도, 겸허는 도교에서 악의 유사물이라고 추측할 수 있다[20][ 21 ] .

서양 철학 [ 편집 ]

니체 [ 편집 ]

프리드리히 니체 는 유대-기독교적 도덕을 부정하고 '선악의 그안 '· ' 도덕의 계보 ' 속에서 비선의 본래의 기능은 약자의 노예도덕에 의해 종교적인 악의 개념으로 사회적으로 변용되어 주인(강자)에게 반감을 안는 대중을 억압했다는 것을 주장했다.

아인 랜드 [ 편집 ]

아인 랜드는 '이기주의라는 기개---에고이즘을 적극적으로 긍정한다'에서 “이성은 인간의 기본적인 생존 수단이기 때문에 이성적 존재가 살기에 적합한 것이 선한 것이다. 반대로 이성적 존재가 사는 것을 부정·방해·파괴하는 것이 나쁜 것”이라고 쓰고 있다. 이 생각은 '어깨를 으쓱하는 아틀라스'에서 더욱 반죽되고 있으며, '생각하는 것은 인간의 유일한 기본적인 미덕이다. 가진 기본적인 악덕, 즉 모든 악의 근원은 사람이 모두 실제로는 하고 있는데 하고 있다고 해서 인정하려고 하지 않는 이름도 없는 행위, 즉 자신의 의식을 고의로 정지하는 것, 생각할 때까지 어쨌든 맹인은 부인하지만 실제로는 보지 않겠다. 어떤 것을 인식하는 것을 거부하는 한 그것은 존재하지 않거나 자신이 '그것은 나쁘다'는 평결을 내리지 않는 한 A는 A가 아니다는 암묵적인 전제에 근거한 판단을 피하는 마음 속의 안개를 일으킨다 행위다.”라고 있다.

스피노자 [ 편집 ]

바루프 데 스피노자 는 이렇게 말했다.

| " | 1. 선에 의해 사람들이 유용하다고 사람들이 당연히 알고 있는 것을 내가 이해할 수 있게 된다. 2. 반대로 악으로 인해 사람들이 선한 것을 가지려고 하는 것을 방해한다고 사람들이 당연히 알고 있는 것을 이해한다 [22] . | " |

스피노자는 중반 수학적인 문체를 사용해, 「에티카」 제4부에서 말한 정의로부터 증명·설명할 수 있다고 자신이 주장하고 있는 추가 명제에 대해서 말하고 있다 [22] :

- 명제 8 “선과 악의 지식은 우리가 의식하는 한 기쁨 혹은 슬픔의 기분 밖에 없다.”

- 명제 30 "우리의 본성에서 공유되는 것을 가지는 것을 통해 악한 것은 있을 수 없지만, 어떤 것이 우리에게 악인 한, 그 어떤 것은 우리와 다를 수 없다."

- 명제 64 "악의 지식은 부적절한 지식이다."

- 추론「그러므로 사람의 마음속에 적절한 지식밖에 없으면 나쁜 생각이 형성되지 않을 것이다.」

- 명제 65. “이성의 인도를 따르면 두 가지 선한 것 중 더 선한 것을 선택하게 되고 두 가지 나쁜 것 중 더 나쁘지 않은 분을 선택한다.”

- 명제 68 "인간이 자유롭게 태어나면 자유인 한 그 인간은 좋은 생각도 나쁜 생각도 가지지 않는다."

이상의 니체, 랜드, 스피노자와 같은 철학적 고찰은 후술하는 신학적 고찰과 비교할 수 있고 대조를 이루지만, 니체와 랜드는 무신론자이며 스피노자는 그렇지 않다는 것이 지적 된다 .

심리학 [ 편집 ]

칼 융 [ 편집 ]

칼 구스타프 융은 '욥에 대한 대답'과 그 밖의 저작으로 악을 '악마의 암흑면'이라고 말하고 있다. 사람은 타인에게 다가가는 그림자를 생각해 그리므로, 악은 자신의 외부에 있는 것이라고 믿기 쉽다. 융은 예수의 이야기를 자신의 그림자에 직면하는 하나님의 이야기로 해석했다 [23] .

짐벌도 [ 편집 ]

2007년 필립 짐벌도 는 사람들이 집합적 정체성의 결과로 사악한 행동을 취할 수 있다고 주장했다. 이 가설은 그가 이전에 스탠포드 감옥 실험을 경험했던 것에 기초하여 저서 "The Lucifer Effect : Understanding How Good People Turn Evil"에서 발표되었다 [24] .

종교 [ 편집 ]

종교 는 종종 계율 로 악을 규정한다. 그것에 근거하여 금지되고 있는 것(금기)은, 그 시조나 개조에 관한 것이나, 그것이 발달한 문화권에 있어서의 생활 규범을 모티브로 한 것 등이 있다. 중동의 조로아스터교 는 빛(선)과 어둠(악)으로 세계를 포착하고 있으며, 이후의 일신교 에 있어서의 신과 악마 의 대립이라는 개념에 영향을 주었다고 한다. 일신교에서는 유대교 의 십계명 과 기독교의 일곱 대죄 등이 유명하다.

불교 [ 편집 ]

불교 의 이원성은 첫째로 고통과 깨달음 사이에 있다는 것은 불교의 내부에는 선과 악의 대립을 닮은 것은 직접적으로 언급되지 않기 때문이다. 그러나 붓다 의 일반적인 가르침을 바탕으로 불교 철학 의 체계 내의 고통은 "악"에 상당한다고 추측될 수 있다" [25] [26] .

사실 이것은 1) 세 가지 이기적인 감정 - 욕망, 증오, 허위; 또는 2) 육체적, 언어적 행동에서 그들이 나타나는 것을 언급 할 수 있습니다. 십계명 (불교) 참조. 특히 '악'은 현세의 행복, 더 나은 환생, 윤회에서의 해탈, 붓다의 진정으로 하여 완전한 깨달음(三藐三菩提)을 방해하는 것을 가리킨다. 무지는 모든 악의 근원으로 여겨진다 [27] .

힌두교 [ 편집 ]

힌두교 에서 달마 , 즉 질서와 정의의 준수를 나타내는 개념은 세계를 선과 악으로 분명히 이분하고 달마를 세우고 호지하기 위해서는 때때로 전쟁이 이루어질 필요가 있다고 설명한다. 이 전쟁은 달마 유다라고 불린다. 이 선악의 구별은 힌두교 서사시 라마야나 와 마하버 라타 모두에서 매우 중요하다.

이슬람 [ 편집 ]

이슬람 에서는 이원론적인 의미로 선과 독립적으로 선과 대등한 기본적·보편적 원리로서의 절대적인 악은 존재하지 않는다. 이슬람에서는 개별 사람에 의해 선한 것으로 느껴지지만 나쁘다고 느껴지지만 모든 것은 알라에게 유래한다고 믿는 것이 본질적 이라고 여겨지고 있다. 그리고, 「악」이라고 느껴지는 것은 자연스럽게 일어나는 것(자연 재해나 병)인지 알라의 명령에 뒤떨어지는 인간의 자유 의사 에 의해서 일어나는 것의 어느 쪽인가라고 된다. 이슬람의 사고 방식에서는 악은 원인이 아니라 결과이다 .

"알라를 뒤집어서 악이나 악행이 이루어지면 큰 칼리마(즉 샤하다 )를 주창하는 자는 악인이 악행을 이루는 것을 멈출 수 없게 된다."

유대-기독교 사상 [ 편집 ]

악은 선이 아니다. 성경 에서는 악은 혼자 있는 상태라고 정의된다( 창세기 2:18 ). 이 의미에서는 악이란 가치관이나 행동에 관하여 사회를 뒤엎고 사회 외부에 있는 것으로 간주될 수 있다.

기독교 변증자 윌리엄 레인 크레이그 처럼, 악을 도덕적 악 즉 누군가가 겪는 해와 자연 악, 즉 자연 재해와 질병, 다른 사람이 의도하지 않은 원인의 결과로 발생하는 해 그리고 나누어 생각하는 사람도 있다. 자연악은 변신론 에서 특히 중요한 개념이다. 왜냐하면 자연악은 누군가의 자유 의사에 의해서 일어났다고 단순히 설명할 수 없기 때문이다.

기독교 [ 편집 ]

기독교 신학 에서는 악의 개념은 구약 성경 과 신약 성경 에서 설명된다. 구약 성경에서는 타 천사 의 장 사탄 과 같은 부적절하고 열등한 것과 똑같이 하나님을 반항하는 것이 악이라고 이해된다 [28] . 신약 성경에서는 그리스어 단어 "포네로스"가 부적절함을 나타내는 데 사용되고 "카코스"가 인간의 영분 내에서 하나님에 대한 반항을 언급하는데 사용된다 [29] . 공식적으로, 가톨릭 교회 에서 악의 이해는 도미니코회의 신학자 토마스 아퀴나스 에 의존한다. 그는 저서 『신학대전』에서 악을 선의 부족·결핍이라고 정의하고 있다 [30] . 프랑스계 미국인 신학자 앙리 브로셰 는 신학적 개념으로는 악은 “부당한 실재. 있다 [31] .

유대교 [ 편집 ]

유대교 에서 악은 하나님을 버린 결과이다 ( 신명기 28:20). 유대교에서는 톨러 ( 타나하 참조)에 기록된 것과 같은 신의 법과 미슈너나 탈무드에 제시된 법과 의식 을 따르는 것이 강조된다.

유대교에서는 교파에 따라서는 악을 사탄과 같은 형태로 의인화하지 않는다. 대신에, 인간의 마음은 생래 기만으로 향하기 쉬운 것이지만 인간은 자신의 선택에 관하여 판단을 맡고 있다고 생각되고 있다. 또 다른 교파에서는 인간은 태어난 시점에서는 선에도 악에도 방향을 붙이지 않았다고 여겨진다. 유대교에서 사탄은 하나님을 반역하는 것이 아니라 오히려 하나님의 생명으로 인간을 시험하는 것으로 간주되며, 악은 위의 기독교 교파처럼 선택의 원인으로 간주됩니다. .

| " | 빛을 만들어 어둠을 창조하고 평화를 만들어 재앙을 상상하는 자; 나는 이 모든 것을 행하는 주님이다. | " |

—이사야 45:7 NASB | ||

일부 문화와 철학에서 악은 의미와 이유가 없어도 태어날 것으로 믿어진다 (네오플라토니즘에서는 이것은 부조리한 악이라고 불린다). 일반적으로 기독교에서는 이러한 일을 믿지 않지만 선지자 이사야 는 하나님이 모든 원인임을 나타냅니다 (Isa.45 : 7) .

비삼위일체파 [ 편집 ]

몰몬교 신학에서는 인생이란 믿음을 시험하는 것이며, 인성 중에서 인간의 선택이 구제계획의 중심을 이루는 것으로 여겨진다. 악이란 인간이 하나님의 본성을 발견하는 것을 방해하는 것이라고 한다. 인간은 악에 물들지 않고 하나님께 귀환하도록 선택해야 한다고 믿어진다.

그리스도인 과학은 자연의 선에 대한 무해함으로 인한 것으로 믿어진다. 자연의 선은 올바른 (영혼) 관점에서 볼 때 본성상 완전한 것으로 이해된다. 하나님의 실재에 대한 오해에 의해 잘못된 선택이 생겨, 그것이 즉 악이 된다. 따라서 악의 근원이되는 다양한 힘과 악의 근원 인 하나님은 부인합니다. 대신 악의 출현은 선의 개념을 오해한 결과라고 여겨진다. 가장 '악'인 사람이라도 악 그 자체를 추구하고 있는 것이 아니라, 잘못된 생각으로부터 어떠한 선을 실현하려고 하고, 결과적으로 부정을 일해 버린다고 크리스천 사이언티스트들은 주장하고 있다 .

조로아스타교 [ 편집 ]

페르시아인 의 본래 종교인 조로아스타교 에서는 세계는 신 아 프라 마즈다 (오플마즈드라고도 불린다)와 악령 앙라 만유 (아리만이라고도 불린다)와의 싸움의 장으로 여겨진다. 선과 악의 싸움의 최종결착은 심판의 날에 일어나고, 그 때에 살고 있는 사람은 모두 불길의 다리로 이끌려, 악한 자들은 쓰러져 영구적으로 부활하지 않는다고 한다. 페르시아인들의 믿음에 의하면 천사 와 성인 은 사람들이 선으로 가는 길을 걷는 데 도움이 되는 존재이다.

악에 관한 철학적 문제 [ 편집 ]

악은 보편적입니까? [ 편집 ]

근본적인 문제는, 악의 보편적·초월론적인 정의가 존재하는지 아닌지, 즉, 악은 사람의 사회적·문화적 배경에 의해 결정되고 있는 것에 지나지 않는 것인가라는 것입니다. 이다 . 강간 이나 살인 처럼 악이라고 보편적으로 생각되는 행동이 존재한다고 C.S. 루이스 가 '인간폐절'에서 말하고 있다. 그러나 강간과 살인이 사회적 맥락에서 선호되는 경우가 많기 때문에 C.S. 루이스의 주장에는 의문이 던져진다. 그래도 강간이라는 단어는 정의상 나쁜 행위를 가리키는 데 사용되는 것을 필요로 한다는 것은 이 개념은 타인에게 성폭력을 가하는 것을 가리키기 때문이라고 주장하는 사람도 있다. 19세기 중반까지는 미국 과 많은 나라에서 노예제가 행해지고 있었다. 자주 있는 것이지만, 이러한 윤리적 경계의 침범은 거기로부터 이익을 얻기 위해서 행해졌다. 아마도 노예제는 항상 똑같고 객관적으로 악한 것이지만 노예제를 하려는 사람들은 그것을 정당화하려고 한다.

제2차 세계대 전기 나치는 제노 사이드 를 정당화했지만 [32] , 르완다 학살 때, 후츠 의 인 테라함웨 도 같은 일을 했다 [33] [34] . 그러나 이러한 잔학 행위의 실행범은 자신의 행위를 제노사이드라고 부르는 것을 피했다는 것은 제노사이드라는 말에 의해 정확하게 나타나는 행위의 객관적인 의미는 특정 인간 집단을 부당하게 죽이는 것이기 때문에 그러나 적어도 부당하게 고통받은 사람들은 이 행위를 악이라고 이해한다. 악은 문화로부터 독립적이며 행동이나 그 의도와 관련에 연동하고 있다고 보편주의자들은 생각하고 있다. 그러므로 나치즘과 후츠의 인테라함웨의 이데올로기적인 주도자는 제노사이드의 실행을 허용(또는 도덕적으로 인정받는다고 생각)하지만 제노사이드는 "근본적으로"또는 "보편적으로"악 라는 신념에 근거하면 제노사이드를 선동하는 사람들은 사실은 나쁘다는 것이다 . 악을 일하는 것은 항상 나쁘지만 악을 일하는 자는 완전히 악한 존재도 선한 존재도 아니라고 주장하는 보편주의자도 있는 것 같다. 예를 들어 막대기가 있는 사탕을 훔친 사람이 완전히 나빠진다는 것은 오히려 지지할 수 없는 입장이라는 것이다. 그러나 보편주의자는 인간은 분명히 선한 인생이나 분명히 악한 인생을 선택할 수 있으며, 대량 학살을 하는 독재는 물론 후자라고 주장하고 있다 .

악의 본성에 대한 생각은 다음과 같은 네 가지 상반된 입장 중 하나에 침착하기 쉽습니다.

- 절대주의(윤리) 에서는 선악이란 하나님, 신들, 자연, 도덕률, 공통 센스 , 그 외의 근거에 의해 세워지는 불변의 개념이라고 생각한다 [35] .

- 허무주의(윤리) 는 선악이라는 것은 무의미한 개념으로, 자연적으로는 윤리의 구성요소가 되는 것 등 존재하지 않는다고 주장한다.

- 상대주의(윤리) 에서는 선악의 기준이 되는 것은 지역마다의 문화, 관습, 고정관념의 산물뿐이라고 생각한다.

- 보편주의(윤리) 란 절대주의자가 말하는 도덕률과 상대주의적 관점의 화해점을 찾아내려는 시도이다. 보편주의는 도덕률은 어느 정도 가변적일 뿐이며, 무엇이 진정으로 선 또는 악인지는 전체 인류를 통해 무엇이 악인지 조사함으로써 결정될 수 있다고 주장한다. 샘 해리스 는 보편적인 도덕률은 뇌생물학이 자극을 조사하는 방법에 근거하여 물리적으로나 정신적으로 계량 가능한 행운의 단위를 이용함으로써 이해할 수 있다고 말한다. [36] .

플라톤 은 선을 이루는 방법은 상대적으로 적고 악을 이루는 방법은 한계가 없다고 썼다. 또한 그 때문에 악을 이루는 방법이 우리의 삶에 큰 영향을 미치고 다른 사람의 삶에 고통을 줄 수 있다고 한다. 이 때문에 도덕적 규칙을 책정하고 실시하는데 있어서 중요한 것은 선을 촉진하는 것보다 오히려 악을 방지하는 것이라고 버나드 가트와 같은 철학자가 주장하고 있다 [ .

악은 유용한 개념인가? [ 편집 ]

나쁜 「인간」등 존재하지 않고, 「행동」만이 악이라고 생각할 수 있다고 주장하는 학파가 존재한다. 심리학자·중재인 마샬 로젠버그 는 폭력의 기원은 바로 '악' '나쁜'이라는 개념 그 자체라고 주장하고 있다. 로젠버그는 우리가 누군가를 나쁘거나 악이라고 레텔 붙이면 비난을 주고 싶은 욕망이 레텔 붙여서 가져온다고 말한다. 이로 인해 우리가 상처를 입은 사람에 대해 무언가를 느끼지 않게 되기 쉽다. 독일인이 다른 민족에 대하여 보통은 하지 않는 일을 하는데 있어서 열쇠가 된 나치 독일에서의 언어의 사용에 대해서 그는 언급하고 있다. 그는 악의 개념과 나쁜 것으로 간주되는 것에 대해 벌을 주는 벌을 주는 것을 통한 정의-인과응보-를 만들어내려는 사법제도를 연결시킨다. 그는 이 접근법을 악의 개념이 존재하지 않는 문화에서 그가 발견한 것과 비교한다. 그러한 문화에서 사람이 누군가를 해칠 때 그들은 자신과 속한 지역 사회와 어울리지 않는 것으로 믿어지고 질병으로 간주되며, 자신과 다른 사람들과 어울릴 수있는 새로운 도량법 가 꺼낸다.

심리학자 앨버트 엘리스 는 논리 정동 행동 치료 ( 영문 : Rational Emotive Behavioral Therapy )라고 불리는 그의 학파에서 비슷한 주장을 하고 있다. 분노의 기원과 타인을 해치고 싶다는 욕구는 거의 항상 타자에 관한 묵시적 또는 명시적인 다양한 철학적 신념에 연결되어 있다고 그는 말한다. 게다가 이런 다양한 비밀 혹은 공연의 신념 혹은 협단을 갖지 않으면 대부분의 경우 폭력에 호소하는 경향은 감퇴한다고 그는 주장하고 있다.

한편, 미국의 중요한 정신과 의사 모건 스콧 펙 은 악을 "호전적인 무지"로 간주하고있다 [37] . 유대-기독교에 있어서의 「죄」의 개념은 본래 인간이 「손해」라고 완성에 이르지 않는 과정으로서의 죄이다. 이에 많은 사람들은 적어도 어느 정도는 알고 있지만, 실제로 악하고 호전적인 사람들은 자신이 눈치채고 있는 것을 인정하지 않는다고 펙은 주장하고 있다. 특히 무고한 죄를 받는 사람(자주 아이나 약한 입장의 사람들)을 선택해 악행을 이룬다는 결과에 이르는 유해한 독선성이야말로 악의 특징이라고 펙은 생각하고 있다. 펙이 악인이라고 부르는 종류의 사람들은 자신의 양심에서 (자기 기만을 통해) 도망 숨어 있으며,이 점에서 사이코 패스에서 분명히 양심이 부족한 것과는 구별된다고 펙은 생각 하고 있다.

- 죄에서 벗어나 자기 이미지를 완벽한 것으로 유지하겠다는 의도로 자기기만을 계속하고 있다

- 자기 기만의 결과로 타인도 속이고

- 자신의 죄를 매우 좁은 범위의 대상에 투영하고 타인을 스케이프 고트하는 한편 자신을 모두와 함께 정상적으로 보여준다(“그에 대한 그들의 불감수성은 선택적”)[39 ]

- 일반적으로 다른 사람을 속삭이는 것과 똑같이 자기 기만을 위해 외설적인 사랑으로 싫어한다.

- 정치적 (감정적) 힘을 악용한다 ( "인간의 의지가 공개적으로 또는 비밀리에 타인에게 부과를 받게하는 것") [40]

- 높은 수준의 사회적 지위를 유지하고 이를 위해 항상 거짓말

- 자신의 죄에 관하여 일관된다. 악당은 저지른 죄의 크기 보다는 오히려 (파괴성이) 지속되는 것을 특징으로 한다

- 자신이 일으킨 악의 피해자의 시점에 서서 생각할 수 없다

- 비판 기타 나르시시즘을 해치는 행위를 받았을 때 몰래 견딜 수 없다

어떤 종류의 제도도 악일 가능성이 있다고 그는 생각하고 있다는 것은 선미 마을 학살 사건 과 그것이 은폐하려고 한 것에 관한 그의 논의에 나타나고 있는 것이다. 이 정의에 따르면 범죄적 테러리즘과 국가 테러리즘도 악으로 간주될 수 있다.

필요악 [ 편집 ]

마르틴 루터 는 작은 악이 부정하기 어려운 선이 될 수 있음을 인정했다. “당신의 마시는 동료의 사회를 찾고, 마시고, 놀고, 외설을 하고 즐기십시오. "죄를 범하라"고 그는 썼다 [41] .

정치철학이 있는 학파에서는 지도자는 선악에 관심을 가지지 않고 실용성만을 바탕으로 행동해야 한다고 생각된다. 정치에 대한 이 접근법은 니콜로 마카벨리가 주창한 것이다. 그는 16세기 피렌체의 저술가 로 정치인들에게 “사랑받는 것보다 두려워하는 것이 훨씬 안전하다”고 조언 했다 .

레알 폴리티크( 독 : Realpolitik )라고 불리기도 하는 현실주의 나 신 현실주의 의 국제 관계론에 근거하면, 정치가는 국제 정치에 있어서는 절대적인 도덕·윤리가 있다는 생각을 분명히 부정하고 , 개인의 관심, 정치적 생존, 무력 외교를 중시하는 것을 선호해야 한다는 것이다. 이것은 이러한 국제관계론을 외우는 자들이 분명히 비도덕적이고 위험하다고 간주하는 세계를 설명하는데 있어서 더 정확해질 것이라고 그들은 생각하고 있다. 정치학에서 현실주의자들은 대부분 정치적 지도자들에게만 부과되는 '고도의 도덕적 의무'를 주장함으로써 그들의 사고방식을 정당화하고 있다. 이 주장 하에서 가장 큰 악은 국가가 자신이나 그 국민을 지킬 수 없다는 것이다. 마카벨리는 이렇게 썼다. 실현되고 군주에게 행복이 되는 특성이 존재한다 [42] .”

관련 항목 [ 편집 ]

참고 문헌 [ 편집 ]

- Baumeister, Roy F. (1999) Evil: Inside Human Violence and Cruelty . New York: AWH Freeman / Owl Book

- Bennett, Gaymon, Hewlett, Martinez J , Peters, Ted , Russell, Robert John (2008). The Evolution of Evil . Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-525-56979-5

- Katz, Fred Emil (1993) "Ordinary People and Extraordinary Evil", [SUNY Press], ISBN 0-7914-1442-6 ;

- Katz, Fred Emil (2004) "Confronting Evil", [SUNY Press], ISBN 0-7914-6030-4 .

- Oppenheimer, Paul (1996). Evil and the Demonic: A New Theory of Monstrous Behavior . New York: New York University Press . ISBN 0-8147-6193-3

- Shermer, M. (2004). The Science of Good & Evil. New York: Time Books. ISBN 0-8050-7520-8

- Steven Mintz, John Stauffer, ed (2007). The Problem of Evil: Slavery, Freedom, and the Ambiguities of American Reform . University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 9781558495708

- Stapley, AB & Elder Delbert L., "Using Our Free Agency". Ensign May 1975: 21

- Vetlesen, Arne Johan (2005) " Evil and Human Agency - Understanding Collective Evildoing " New York: Cambridge University Press . ISBN 978-0-521-85694-2

- Wilson, William McF., and Julian N. Hartt. "Farrer's Theodicy." In David Hein and Edward Hugh Henderson (eds), Captured by the Crucified: The Practical Theology of Austin Farrer . New York and London: T & T Clark / Continuum, 2004. ISBN 0-567-02510-1

- 영혼 살인 앨리스 미러

- 쾌활하고 거짓말을하는 사람들 M. Scott Pek

- 악에 대해 에리히 프롬

각주 [ 편집 ]

- ↑ Griffin, David Ray (2004) [1976]. God, Power, and Evil: a Process Theodicy . Westminster. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-664-22906-1

- ↑ a b “ Evil ”. Oxford University Press (2012년). 2019년 12월 8일에 확인함.

- ↑ Ervin Staub. Overcoming evil: genocide, violent conflict, and terrorism . New York: Oxford University Press, p. 32.

- ↑ Matthews, Caitlin; Matthews, John (2004). Walkers Between the Worlds: The Western Mysteries from Shaman to Magus . New York City: Simon & Schuster . p. 173. ASIN B00770DJ3G

- ^ de Hulster, Izaak J. (2009). Iconographic Exegesis and Third Isaiah . Heidelberg, Germany: Mohr Siebeck Verlag . pp. 136-37. ISBN 978-3-16-150029-9

- ↑ a b Ingram, Paul O.; Streng, Frederick John (1986). Buddhist-Christian Dialogue: Mutual Renewal and Transformation . Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press . pp. 148-49. ISBN 978-1-55635-381-9

- ↑ Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy "Ethics"

- ^ a b c Roy F. Baumeister " Human Evil: The Mythical and the True Causes of Violence " Florida State University. archive

- ↑ Stern, Fritz; Lifton, Robert Jay (1986). “The Nazi Doctors : Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide” . Foreign Affairs 65 (2): 404. doi : 10.2307/20043033 . ISSN 0

- ↑ Dower, John W. (2017), War without mercy : race and power in the pacific war , Tantor Media, ISBN 978-1-5414-2124-0 , OCLC 982707419 2019년 12월 8일에 확인함.

- ↑ Hesse, Petra; Mack, John E. (1991). Rieber, Robert W.. ed (영어). The Psychology of War and Peace: The Image of the Enemy . Boston, MA: Springer US. pp. 131-153 . doi : 10.1007/978-1-4899-0747-9_6 . ISBN 978-1-4899-0747-9

- ↑ Baumeister, Roy F. (2005). The cultural animal : human nature, meaning, and social life . Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-516703-1 . OCLC 770765517

- ↑ Baumeister, Roy F.; Smart, Laura; Boden, Joseph M. (1996). “ Relation of threatened egotism to violence and aggression: The dark side of high self-esteem.” . 33. doi : 10.1037//0033-295x.103.1.5 . ISSN 0033-295X .

- ↑ Bushman, Brad (1998). “ Threatened egotism, narcissism, self-esteem, and directed and displaced aggression: Does self-love or self-hate lead to violence? ”. PsycEXTRA Dataset . 2019년 12월 8일에 확인함.

- ↑ Solomon, Richard L.; Corbit, John D. (1974). “An opponent-process theory of motivation: I. Temporal dynamics of affect.” . Psychological Review 81 (2): 119-145 . ISSN 1939-1471 . _

- ↑ O'Neal, Edgar C. (1994). “Human aggression, second edition, edited by Robert A. Baron and Deborah R. Richardson. New York, Plenum, 1994, xx + 419 pp” (영어). Aggressive Behavior 20 (6): 461-463. doi : 10.1002/1098-2337(1994)20:63.0.CO;2-O . ISSN 1098-2337 .

- ↑ Bushman, Brad J.; Geen, Russell G. (1990). “Role of cognitive-emotional mediators and individual differences in the effects of media violence on aggression.” . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 58 (1): 156- 163. doi : 10.1037/0022-3514.58.1.156 . ISSN 1939-1315 .

- ↑ Baumeister, Roy F. (2006). Losing control : how and why people fail at self-regulation . Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-083140-6 . OCLC 553911110

- ↑ Bushman, BJ; Cooper, HM (1990-05). “ Effects of alcohol on human aggression : an integrative research review” . Psychological Bulletin 107 ( 3): 341-354 . 0033-2909 . PMID 2140902 .

- ↑ Good and Evil in Chinese Philosophy Archived 2006년 5월 29일, at the Wayback Machine . CW Chan

- ↑ History of Chinese Philosophy Feng Youlan, Volume II The Period of Classical Learning (from the Second Century BC to the Twentieth Century AD). Trans. Derk Bodde. Ch. XIV Liu Chiu-Yuan, Wang Shou-jen, and Ming Idealism. part 6 § 6 Origin of Evil . Uses strikingly similar language to that in the etymology section of this article, in the context of Chinese Idealism.

- ^ a b Benedict de Spinoza, Ethics , Part IV Of Human Bondage or of the Strength of the Affects Definitions translated by WH White, Revised by AH Stirling, Great Books vol 31, Encyclopædia Britannica 1952 p.

- ↑ Stephen Palmquist , Dreams of Wholeness : A course of introductory lectures on religion, psychology and personal growth (Hong Kong: Philopsychy Press, 1997/2008), see especially Chapter XI.

- ^ Book website

- ↑ Philosophy of Religion Charles Taliaferro, Paul J. Griffiths, eds. Ch. 35, Buddhism and Evil Martin Southwold p 424

- ↑ Lay Outreach and the Meaning of “Evil Person Taitetsu Unno Archived 2012년 10월 18일, at the Wayback Machine .

- ↑ The Jewel Ornament of Liberation. Gampopa. ISBN 978-1559390927

- ↑ Hans Schwarz, Evil: A Historical and Theological Perspective (Lima, Ohio: Academic Renewal Press, 2001): 42-43.

- ↑ Schwarz, Evil , 75.

- ↑ Thomas Aquinas, SUMMA THEOLOGICA, translated by the Fathers of the English Dominician Province (New York: Benziger Brothers, 1947) Volume 3, q. 72, a. 1, p. 902.

- ↑ Henri Blocher, Evil and the Cross (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press , 1994): 10.

- ↑ Gaymon Bennett, Ted Peters, Martinez J. Hewlett, Robert John Russell (2008). " The evolution of evil ". Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. p.318 .

- ↑ Gourevitch, Phillip (1999). We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will be Killed With our Families . Picador. ISBN 0-31224-335-9

- ↑ “ Frontline: the triumph of evil. ”. 2007년 4월 9일에 확인함.

- ^ url= http://www.vatican.va/archive/catechism/p3s1c1a6.htm

- ↑ Harris, Sam (2004). The End of Faith: Religion, Terror and the Future of Reason . WW Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-03515-8

- ^ a b Peck, M. Scott. (1983;1988). People of the Lie: The hope for healing human evil . Century Hutchinson.

- ↑ Peck, M. Scott. (1978; 1992), The Road Less Travelled . Arrow.

- ↑ Peck, 1983/1988, p105

- ↑ Peck, 1978/1992, p298

- ↑ Martin Luther, Werke , XX, p58

- ↑ a b Niccolo Machiavelli, The Prince , Dante University of America Press, 2003, ISBN 0-937832-38-3 ISBN 978-0-937832-38-7

외부 링크 [ 편집 ]

Evil

Evil, or being bad, in a general sense, is acting out morally incorrect behavior, or the condition of causing unnecessary pain and suffering, thus, containing a net negative on the world.[1]

Evil is commonly seen as the opposite or sometimes absence of good. It can be an extremely broad concept, although in everyday usage it is often more narrowly used to talk about profound wickedness and against common good. It is generally seen as taking multiple possible forms, such as the form of personal moral evil commonly associated with the word, or impersonal natural evil (as in the case of natural disasters or illnesses), and in religious thought, the form of the demonic or supernatural/eternal.[2] While some religions, world views, and philosophies focus on "good versus evil", others deny evil's existence and usefulness in describing people.

Evil can denote profound immorality,[3] but typically not without some basis in the understanding of the human condition, where strife and suffering (cf. Hinduism) are the true roots of evil. In certain religious contexts, evil has been described as a supernatural force.[3] Definitions of evil vary, as does the analysis of its motives.[4] Elements that are commonly associated with personal forms of evil involve unbalanced behavior including anger, revenge, hatred, psychological trauma, expediency, selfishness, ignorance, destruction and neglect.[5]

In some forms of thought, evil is also sometimes perceived as the dualistic antagonistic binary opposite to good,[6] in which good should prevail and evil should be defeated.[7] In cultures with Buddhist spiritual influence, both good and evil are perceived as part of an antagonistic duality that itself must be overcome through achieving Nirvana.[7] The ethical questions regarding good and evil are subsumed into three major areas of study:[8] meta-ethics concerning the nature of good and evil, normative ethics concerning how we ought to behave, and applied ethics concerning particular moral issues. While the term is applied to events and conditions without agency, the forms of evil addressed in this article presume one or more evildoers.

Etymology

The modern English word evil (Old English yfel) and its cognates such as the German Übel and Dutch euvel are widely considered to come from a Proto-Germanic reconstructed form of *ubilaz, comparable to the Hittite huwapp- ultimately from the Proto-Indo-European form *wap- and suffixed zero-grade form *up-elo-. Other later Germanic forms include Middle English evel, ifel, ufel, Old Frisian evel (adjective and noun), Old Saxon ubil, Old High German ubil, and Gothic ubils.[9]

The root meaning of the word is of obscure origin though shown to be akin to modern German übel (noun: Übel, although the noun evil is normally translated as "das Böse") with the basic idea of social or religious transgression.

Chinese moral philosophy

As with Buddhism, in Confucianism or Taoism there is no direct analogue to the way good and evil are opposed although reference to demonic influence is common in Chinese folk religion. Confucianism's primary concern is with correct social relationships and the behavior appropriate to the learned or superior man. Thus evil would correspond to wrong behavior. Still less does it map into Taoism, in spite of the centrality of dualism in that system, but the opposite of the cardinal virtues of Taoism, compassion, moderation, and humility can be inferred to be the analogue of evil in it.[10][11]

European philosophy

In response to the practices of Nazi Germany, Hannah Arendt concluded that "the problem of evil would be the fundamental problem of postwar intellectual life in Europe", although such a focus did not come to fruition.[12]

Spinoza

Baruch Spinoza states

Spinoza assumes a quasi-mathematical style and states these further propositions which he purports to prove or demonstrate from the above definitions in part IV of his Ethics:[13]

- Proposition 8 "Knowledge of good or evil is nothing but affect of joy or sorrow in so far as we are conscious of it."

- Proposition 30 "Nothing can be evil through that which it possesses in common with our nature, but in so far as a thing is evil to us it is contrary to us."

- Proposition 64 "The knowledge of evil is inadequate knowledge."

- Corollary "Hence it follows that if the human mind had none but adequate ideas, it would form no notion of evil."

- Proposition 65 "According to the guidance of reason, of two things which are good, we shall follow the greater good, and of two evils, follow the less."

- Proposition 68 "If men were born free, they would form no conception of good and evil so long as they were free."

Psychology

Carl Jung

Carl Jung, in his book Answer to Job and elsewhere, depicted evil as the dark side of God.[14] People tend to believe evil is something external to them, because they project their shadow onto others. Jung interpreted the story of Jesus as an account of God facing his own shadow.[15]

Philip Zimbardo

In 2007, Philip Zimbardo suggested that people may act in evil ways as a result of a collective identity. This hypothesis, based on his previous experience from the Stanford prison experiment, was published in the book The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil.[16]

Milgram experiment

In 1961, Stanley Milgram began an experiment to help explain how thousands of ordinary, non-deviant, people could have reconciled themselves to a role in the Holocaust. Participants were led to believe they were assisting in an unrelated experiment in which they had to inflict electric shocks on another person. The experiment unexpectedly found that most could be led to inflict the electric shocks,[17] including shocks that would have been fatal if they had been real.[18] The participants tended to be uncomfortable and reluctant in the role. Nearly all stopped at some point to question the experiment, but most continued after being reassured.[17]

A 2014 re-assessment of Milgram's work argued that the results should be interpreted with the "engaged followership" model: that people are not simply obeying the orders of a leader, but instead are willing to continue the experiment because of their desire to support the scientific goals of the leader and because of a lack of identification with the learner.[19][20] Thomas Blass argues that the experiment explains how people can be complicit in roles such as "the dispassionate bureaucrat who may have shipped Jews to Auschwitz with the same degree of routinization as potatoes to Bremerhaven". However, like James Waller, he argues that it cannot explain an event like the Holocaust. Unlike the perpetrators of the Holocaust, the participants in Milgram's experiment were reassured that their actions would cause little harm and had little time to contemplate their actions.[18][21]

Religions

Abrahamic

Baháʼí Faith

The Baháʼí Faith asserts that evil is non-existent and that it is a concept reflecting lack of good, just as cold is the state of no heat, darkness is the state of no light, forgetfulness the lacking of memory, ignorance the lacking of knowledge. All of these are states of lacking and have no real existence.[22]

Thus, evil does not exist and is relative to man. `Abdu'l-Bahá, son of the founder of the religion, in Some Answered Questions states:

"Nevertheless a doubt occurs to the mind—that is, scorpions and serpents are poisonous. Are they good or evil, for they are existing beings? Yes, a scorpion is evil in relation to man; a serpent is evil in relation to man; but in relation to themselves they are not evil, for their poison is their weapon, and by their sting they defend themselves."[22]

Thus, evil is more of an intellectual concept than a true reality. Since God is good, and upon creating creation he confirmed it by saying it is Good (Genesis 1:31) evil cannot have a true reality.[22]

Christianity

Christian theology draws its concept of evil from the Old and New Testaments. The Christian Bible exercises "the dominant influence upon ideas about God and evil in the Western world."[2] In the Old Testament, evil is understood to be an opposition to God as well as something unsuitable or inferior such as the leader of the fallen angels Satan[23] In the New Testament the Greek word poneros is used to indicate unsuitability, while kakos is used to refer to opposition to God in the human realm.[24] Officially, the Catholic Church extracts its understanding of evil from its canonical antiquity and the Dominican theologian, Thomas Aquinas, who in Summa Theologica defines evil as the absence or privation of good.[25] French-American theologian Henri Blocher describes evil, when viewed as a theological concept, as an "unjustifiable reality. In common parlance, evil is 'something' that occurs in the experience that ought not to be."[26]

Islam

There is no concept of absolute evil in Islam, as a fundamental universal principle that is independent from and equal with good in a dualistic sense.[27] Although the Quran mentions the biblical forbidden tree, it never refers to it as the 'tree of knowledge of good and evil'.[27] Within Islam, it is considered essential to believe that all comes from God, whether it is perceived as good or bad by individuals; and things that are perceived as evil or bad are either natural events (natural disasters or illnesses) or caused by humanity's free will. Much more the behavior of beings with free will, then they disobey God's orders, harming others or putting themselves over God or others, is considered to be evil.[28] Evil does not necessarily refer to evil as an ontological or moral category, but often to harm or as the intention and consequence of an action, but also to unlawful actions.[27] Unproductive actions or those who do not produce benefits are also thought of as evil.[29]

A typical understanding of evil is reflected by Al-Ash`ari founder of Asharism. Accordingly, qualifying something as evil depends on the circumstances of the observer. An event or an action itself is neutral, but it receives its qualification by God. Since God is omnipotent and nothing can exist outside of God's power, God's will determine, whether or not something is evil.[30]

Rabbinic Judaism

In Judaism and Jewish theology, the existence of evil is presented as part of the idea of free will: if humans were created to be perfect, always and only doing good, being good would not mean much. For Jewish theology, it is important for humans to have the ability to choose the path of goodness, even in the face of temptation and yetzer hara (the inclination to do evil).[31][32]

Ancient Egyptian

Evil in the religion of ancient Egypt is known as Isfet, "disorder/violence". It is the opposite of Maat, "order", and embodied by the serpent god Apep, who routinely attempts to kill the sun god Ra and is stopped by nearly every other deity. Isfet is not a primordial force, but the consequence of free will and an individual's struggle against the non-existence embodied by Apep, as evidenced by the fact that it was born from Ra's umbilical cord instead of being recorded in the religion's creation myths.[33]

Indian

Buddhism

The primal duality in Buddhism is between suffering and enlightenment, so the good vs. evil splitting has no direct analogue in it. One may infer from the general teachings of the Buddha that the catalogued causes of suffering are what correspond in this belief system to 'evil'.[34][35]

Practically this can refer to 1) the three selfish emotions—desire, hate and delusion; and 2) to their expression in physical and verbal actions. Specifically, evil means whatever harms or obstructs the causes for happiness in this life, a better rebirth, liberation from samsara, and the true and complete enlightenment of a buddha (samyaksambodhi).

"What is evil? Killing is evil, lying is evil, slandering is evil, abuse is evil, gossip is evil: envy is evil, hatred is evil, to cling to false doctrine is evil; all these things are evil. And what is the root of evil? Desire is the root of evil, illusion is the root of evil." Gautama Siddhartha, the founder of Buddhism, 563–483 BC.

Hinduism

In Hinduism, the concept of Dharma or righteousness clearly divides the world into good and evil, and clearly explains that wars have to be waged sometimes to establish and protect Dharma, this war is called Dharmayuddha. This division of good and evil is of major importance in both the Hindu epics of Ramayana and Mahabharata. The main emphasis in Hinduism is on bad action, rather than bad people. The Hindu holy text, the Bhagavad Gita, speaks of the balance of good and evil. When this balance goes off, divine incarnations come to help to restore this balance.[36]

Sikhism

In adherence to the core principle of spiritual evolution, the Sikh idea of evil changes depending on one's position on the path to liberation. At the beginning stages of spiritual growth, good and evil may seem neatly separated. Once one's spirit evolves to the point where it sees most clearly, the idea of evil vanishes and the truth is revealed. In his writings Guru Arjan explains that, because God is the source of all things, what we believe to be evil must too come from God. And because God is ultimately a source of absolute good, nothing truly evil can originate from God.[37]

Sikhism, like many other religions, does incorporate a list of "vices" from which suffering, corruption, and abject negativity arise. These are known as the Five Thieves, called such due to their propensity to cloud the mind and lead one astray from the prosecution of righteous action.[38] These are:[39]

One who gives in to the temptations of the Five Thieves is known as "Manmukh", or someone who lives selfishly and without virtue. Inversely, the "Gurmukh, who thrive in their reverence toward divine knowledge, rise above vice via the practice of the high virtues of Sikhism. These are:[40]

- Sewa, or selfless service to others.

- Nam Simran, or meditation upon the divine name.

Question of a universal definition

A fundamental question is whether there is a universal, transcendent definition of evil, or whether one's definition of evil is determined by one's social or cultural background. C. S. Lewis, in The Abolition of Man, maintained that there are certain acts that are universally considered evil, such as rape and murder. However, the rape of women, by men, is found in every society, and there are more societies that see at least some versions of it, such as marital rape or punitive rape, as normative than there are societies that see all rape as non-normative (a crime).[41] In nearly all societies, killing except for defense or duty is seen as murder. Yet the definition of defense and duty varies from one society to another.[42] Social deviance is not uniformly defined across different cultures, and is not, in all circumstances, necessarily an aspect of evil.[43][44]

Defining evil is complicated by its multiple, often ambiguous, common usages: evil is used to describe the whole range of suffering, including that caused by nature, and it is also used to describe the full range of human immorality from the "evil of genocide to the evil of malicious gossip".[45]: 321 It is sometimes thought of as the generic opposite of good. Marcus Singer asserts that these common connotations must be set aside as overgeneralized ideas that do not sufficiently describe the nature of evil.[46]: 185, 186

In contemporary philosophy, there are two basic concepts of evil: a broad concept and a narrow concept. A broad concept defines evil simply as any and all pain and suffering: "any bad state of affairs, wrongful action, or character flaw".[47] Yet, it is also asserted that evil cannot be correctly understood "(as some of the utilitarians once thought) [on] a simple hedonic scale on which pleasure appears as a plus, and pain as a minus".[48] This is because pain is necessary for survival.[49] Renowned orthopedist and missionary to lepers, Dr. Paul Brand explains that leprosy attacks the nerve cells that feel pain resulting in no more pain for the leper, which leads to ever increasing, often catastrophic, damage to the body of the leper.[50]: 9, 50–51 Congenital insensitivity to pain (CIP), also known as congenital analgesia, is a neurological disorder that prevents feeling pain. It "leads to ... bone fractures, multiple scars, osteomyelitis, joint deformities, and limb amputation ... Mental retardation is common. Death from hyperpyrexia occurs within the first 3 years of life in almost 20% of the patients."[51] Few with the disorder are able to live into adulthood.[52] Evil cannot be simply defined as all pain and its connected suffering because, as Marcus Singer says: "If something is really evil, it can't be necessary, and if it is really necessary, it can't be evil".[46]: 186

The narrow concept of evil involves moral condemnation, therefore it is ascribed only to moral agents and their actions.[45]: 322 This eliminates natural disasters and animal suffering from consideration as evil: according to Claudia Card, "When not guided by moral agents, forces of nature are neither "goods" nor "evils". They just are. Their "agency" routinely produces consequences vital to some forms of life and lethal to others".[53] The narrow definition of evil "picks out only the most morally despicable sorts of actions, characters, events, etc. Evil [in this sense] ... is the worst possible term of opprobrium imaginable”.[46] Eve Garrard suggests that evil describes "particularly horrifying kinds of action which we feel are to be contrasted with more ordinary kinds of wrongdoing, as when for example we might say 'that action wasn't just wrong, it was positively evil'. The implication is that there is a qualitative, and not merely quantitative, difference between evil acts and other wrongful ones; evil acts are not just very bad or wrongful acts, but rather ones possessing some specially horrific quality".[45]: 321 In this context, the concept of evil is one element in a full nexus of moral concepts.[45]: 324

Philosophical questions

Approaches

Views on the nature of evil belong to the branch of philosophy known as ethics—which in modern philosophy is subsumed into three major areas of study:[8]

- Meta-ethics, that seeks to understand the nature of ethical properties, statements, attitudes, and judgments.

- Normative ethics, investigates the set of questions that arise when considering how one ought to act, morally speaking.

- Applied ethics, concerned with the analysis of particular moral issues in private and public life.[8]

Usefulness as a term

There is debate on how useful the term "evil" is, since it is often associated with spirits and the devil. Some see the term as useless because they say it lacks any real ability to explain what it names. There is also real danger of the harm that being labeled "evil" can do when used in moral, political, and legal contexts.[47]: 1–2 Those who support the usefulness of the term say there is a secular view of evil that offers plausible analyses without reference to the supernatural.[45]: 325 Garrard and Russell argue that evil is as useful an explanation as any moral concept.[45]: 322–326 [54] Garrard adds that evil actions result from a particular kind of motivation, such as taking pleasure in the suffering of others, and this distinctive motivation provides a partial explanation even if it does not provide a complete explanation.[45]: 323–325 [54]: 268–269 Most theorists agree use of the term evil can be harmful but disagree over what response that requires. Some argue it is "more dangerous to ignore evil than to try to understand it".[47]

Those who support the usefulness of the term, such as Eve Garrard and David McNaughton, argue that the term evil "captures a distinct part of our moral phenomenology, specifically, 'collect[ing] together those wrongful actions to which we have ... a response of moral horror'."[55] Claudia Card asserts it is only by understanding the nature of evil that we can preserve humanitarian values and prevent evil in the future.[56] If evils are the worst sorts of moral wrongs, social policy should focus limited energy and resources on reducing evil over other wrongs.[57] Card asserts that by categorizing certain actions and practices as evil, we are better able to recognize and guard against responding to evil with more evil which will "interrupt cycles of hostility generated by past evils".[57]: 166

One school of thought holds that no person is evil and that only acts may be properly considered evil. Some theorists define an evil action simply as a kind of action an evil person performs.[58]: 280 But just as many theorists believe that an evil character is one who is inclined toward evil acts.[59]: 2 Luke Russell argues that both evil actions and evil feelings are necessary to identify a person as evil, while Daniel Haybron argues that evil feelings and evil motivations are necessary.[47]: 4–4.1

American psychiatrist M. Scott Peck describes evil as a kind of personal "militant ignorance".[60] According to Peck, an evil person is consistently self-deceiving, deceives others, psychologically projects his or her evil onto very specific targets,[61] hates, abuses power, and lies incessantly.[60][62] Evil people are unable to think from the viewpoint of their victim. Peck considers those he calls evil to be attempting to escape and hide from their own conscience (through self-deception) and views this as being quite distinct from the apparent absence of conscience evident in sociopaths. He also considers that certain institutions may be evil, using the My Lai Massacre to illustrate. By this definition, acts of criminal and state terrorism would also be considered evil.

Necessity

Martin Luther argued that there are cases where a little evil is a positive good. He wrote, "Seek out the society of your boon companions, drink, play, talk bawdy, and amuse yourself. One must sometimes commit a sin out of hate and contempt for the Devil, so as not to give him the chance to make one scrupulous over mere nothings ... "[63]

The international relations theories of realism and neorealism, sometimes called realpolitik advise politicians to explicitly ban absolute moral and ethical considerations from international politics, and to focus on self-interest, political survival, and power politics, which they hold to be more accurate in explaining a world they view as explicitly amoral and dangerous. Political realists usually justify their perspectives by stating that morals and politics should be separated as two unrelated things, as exerting authority often involves doing something not moral. Machiavelli wrote: "there will be traits considered good that, if followed, will lead to ruin, while other traits, considered vices which if practiced achieve security and well being for the prince."[64]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ "What does Evil mean?". www.definitions.net. Retrieved 2023-12-28.

- ^ a b Griffin, David Ray (2004) [1976]. God, Power, and Evil: a Process Theodicy. Westminster. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-664-22906-1.

- ^ a b "Evil". Oxford University Press. 2012. Archived from the original on July 12, 2012.

- ^ Ervin Staub. Overcoming evil: genocide, violent conflict, and terrorism. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 32.

- ^ Matthews, Caitlin; Matthews, John (2004). Walkers Between the Worlds: The Western Mysteries from Shaman to Magus. New York City: Simon & Schuster. p. 173. ASIN B00770DJ3G. Archived from the original on 2021-09-17. Retrieved 2021-09-17.

- ^ de Hulster, Izaak J. (2009). Iconographic Exegesis and Third Isaiah. Heidelberg, Germany: Mohr Siebeck Verlag. pp. 136–37. ISBN 978-3-16-150029-9.

- ^ a b Ingram, Paul O.; Streng, Frederick John (1986). Buddhist-Christian Dialogue: Mutual Renewal and Transformation. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 148–49. ISBN 978-1-55635-381-9.

- ^ a b c Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy ""Ethics"".

- ^ Harper, Douglas (2001). "Etymology for evil".

- ^ C.W. Chan (1996). "Good and Evil in Chinese Philosophy". The Philosopher. LXXXIV. Archived from the original on 2006-05-29.

- ^ Feng, Yu-lan (1983). "Origin of Evil". History of Chinese Philosophy, Volume II: The Period of Classical Learning (from the Second Century B.C. to the Twentieth Century A.D. Translated by Bodde, Derk. New Haven, CN: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02022-8.

- ^ Neiman, Susan (2015). Evil in Modern Thought: An Alternative History of Philosophy. Princeton University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-691-16850-0. OCLC 1294864456.

- ^ a b de Spinoza, Benedict (2017) [1677]. "Of Human Bondage or of the Strength of the Affects". Ethics. Translated by White, W.H. New York: Penguin Classics. p. 424. ASIN B00DO8NRDC.

- ^ "Answer to Job Revisited : Jung on the Problem of Evil".

- ^ Stephen Palmquist, Dreams of Wholeness: A course of introductory lectures on religion, psychology and personal growth (Hong Kong: Philopsychy Press, 1997/2008), see especially Chapter XI.

- ^ "Book website".

- ^ a b Milgram, Stanley (1963). "Behavioral Study of Obedience". Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 67 (4): 371–8. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.599.92. doi:10.1037/h0040525. PMID 14049516. S2CID 18309531. as PDF. Archived April 4, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Blass, Thomas (1991). "Understanding behavior in the Milgram obedience experiment: The role of personality, situations, and their interactions" (PDF). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 60 (3): 398–413. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.60.3.398. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 7, 2016.

- ^ Haslam, S. Alexander; Reicher, Stephen D.; Birney, Megan E. (September 1, 2014). "Nothing by Mere Authority: Evidence that in an Experimental Analogue of the Milgram Paradigm Participants are Motivated not by Orders but by Appeals to Science". Journal of Social Issues. 70 (3): 473–488. doi:10.1111/josi.12072. hdl:10034/604991. ISSN 1540-4560.

- ^ Haslam, S. Alexander; Reicher, Stephen D. (13 October 2017). "50 Years of "Obedience to Authority": From Blind Conformity to Engaged Followership". Annual Review of Law and Social Science. 13 (1): 59–78. doi:10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110316-113710.

- ^ James Waller (February 22, 2007). What Can the Milgram Studies Teach Us... (Google Books). Oxford University Press. pp. 111–113. ISBN 978-0199774852. Retrieved June 9, 2013.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Coll, 'Abdu'l-Bahá (1982). Some answered questions. Translated by Barney, Laura Clifford (Repr. ed.). Wilmette, IL: Baháʼí Publ. Trust. ISBN 978-0-87743-162-6.

- ^ Hans Schwarz, Evil: A Historical and Theological Perspective (Lima, Ohio: Academic Renewal Press, 2001): 42–43.

- ^ Schwarz, Evil, 75.

- ^ Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, translated by the Fathers of the English Dominican Province (New York: Benziger Brothers, 1947) Volume 3, q. 72, a. 1, p. 902.

- ^ Henri Blocher, Evil and the Cross (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 1994): 10.

- ^ a b c Jane Dammen McAuliffe Encyclopaedia of the Qurʼān Brill 2001 ISBN 978-90-04-14764-5 p. 335

- ^ B. Silverstein Islam and Modernity in Turkey Springer 2011 ISBN 978-0-230-11703-7 p. 124

- ^ Jane Dammen McAuliffe Encyclopaedia of the Qurʼān Brill 2001 ISBN 978-90-04-14764-5 p. 338

- ^ P. Koslowski (2013). The Origin and the Overcoming of Evil and Suffering in the World Religions Springer Science & Business Media ISBN 978-94-015-9789-0 p. 37

- ^ Gurkow, Lazer. "Why Did G-d Create Evil?". Chabad. Retrieved October 17, 2023.

- ^ rabbifisdel (2010-07-08). "The Human Dichotomy: Good and Evil | Classical Kabbalist". Retrieved 2023-10-18.

- ^ Kemboly, Mpay (2010). The Question of Evil in Ancient Egypt. London: Golden House Publications.

- ^ Philosophy of Religion Charles Taliaferro, Paul J. Griffiths, eds. Ch. 35, Buddhism and Evil Martin Southwold p. 424

- '^ Lay Outreach and the Meaning of 'Evil Person Taitetsu Unno Archived 2012-10-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Perumpallikunnel, K. (2013). "Discernment: The message of the bhagavad-gita". Acta Theologica. 33: 271. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1032.370.

- ^ Singh, Gopal (1967). Sri guru-granth sahib [english version]. New York: Taplinger Publishing Co.

- ^ Singh, Charan (2013-12-11). "Ethics and Business: Evidence from Sikh Religion". Social Science Research Network. Indian Institute of Management, Bangalore. SSRN 2366249.

- ^ Sandhu, Jaswinder (February 2004). "The Sikh Model of the Person, Suffering, and Healing: Implications for Counselors". International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling. 26 (1): 33–46. doi:10.1023/B:ADCO.0000021548.68706.18. S2CID 145256429.

- ^ Singh, Arjan (January 2000). "The universal ideal of sikhism". Global Dialogue. 2 (1).

- ^ Brown, Jennifer; Horvath, Miranda, eds. (2013). Rape Challenging Contemporary Thinking. Taylor & Francis. p. 62. ISBN 9781134026395.

- ^ Humphrey, J.A.; Palmer, S. (2013). Deviant Behavior Patterns, Sources, and Control. Springer US. p. 11. ISBN 9781489905833.

- ^ McKeown, Mick; Stowell-Smith, Mark (2006). "The Comforts of Evil: Dangerous Personalities in High-Security Hospitals and the Horror Film". Forensic Psychiatry. pp. 109–134. doi:10.1007/978-1-59745-006-5_6. ISBN 9781597450065.

- ^ Milgram, Stanley (2017). Obedience to Authority. Harper Perennial. pp. Foreword. ISBN 9780062803405.

- ^ a b c d e f g Garrard, Eve (April 2002). "Evil as an Explanatory Concept" (Pdf). The Monist. Oxford University Press. 85 (2): 320–336. doi:10.5840/monist200285219. JSTOR 27903775.

- ^ a b c Marcus G. Singer, Marcus G. Singer (April 2004). "The Concept of Evil". Philosophy. Cambridge University Press. 79 (308): 185–214. doi:10.1017/S0031819104000233. JSTOR 3751971. S2CID 146121829.

- ^ a b c d Calder, Todd (26 November 2013). "The Concept of Evil". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- ^ Kemp, John (25 February 2009). "Pain and Evil". Philosophy. 29 (108): 13. doi:10.1017/S0031819100022105. S2CID 144540963. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ "Reviews". The Humane Review. E. Bell. 2 (5–8): 374. 1901.

- ^ Yancey, Philip; Brand, Paul (2010). Fearfully and Wonderfully Made. Zondervan. ISBN 9780310861997.

- ^ Rosemberg, Sérgio; Kliemann, Suzana; Nagahashi, Suely K. (1994). "Congenital insensitivity to pain with anhidrosis (hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathy type IV)". Pediatric Neurology. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 11 (1): 50–56. doi:10.1016/0887-8994(94)90091-4. PMID 7527213. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ Cox, David (27 April 2017). "The curse of the people who never feel pain". BBC. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ Card, Claudia (2005). The Atrocity Paradigm A Theory of Evil. Oxford University Press. p. 5. ISBN 9780195181265.

- ^ a b Russell, Luke (July 2009). "He Did It Because He Was Evil". American Philosophical Quarterly. University of Illinois Press. 46 (3): 268–269. JSTOR 40606922.

- ^ Garrard, Eve; McNaughton, David (2 September 2012). "Speak No Evil?". Midwest Studies in Philosophy. 36 (1): 13–17. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4975.2012.00230.x.

- ^ Card, Claudia (2010). Confronting Evils: Terrorism, Torture, Genocide. Cambridge University Press. p. i. ISBN 9781139491709.

- ^ a b Card, Claudia (2005). The Atrocity Paradigm A Theory of Evil. Oxford University Press. p. 109. ISBN 9780195181265.

- ^ Haybron, Daniel M. (2002). "Moral Monsters and Saints". The Monist. Oxford University Press. 85 (2): 260–284. doi:10.5840/monist20028529. JSTOR 27903772.

- ^ Kekes, John (2005). The Roots of Evil. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801443688.

- ^ a b Peck, M. Scott. (1983, 1988). People of the Lie: The hope for healing human evil. Century Hutchinson.

- ^ Peck, 1983/1988, p. 105

- ^ Peck, M. Scott. (1978, 1992), The Road Less Travelled. Arrow.

- ^ Martin Luther, Werke, XX, p. 58

- ^ Niccolo Machiavelli, The Prince, Dante University of America Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0-937832-38-7

Further reading

- Baumeister, Roy F. (1999). Evil: Inside Human Violence and Cruelty. New York: W.H. Freeman / Owl Book

- Bennett, Gaymon, Hewlett, Martinez J, Peters, Ted, Russell, Robert John (2008). The Evolution of Evil. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-525-56979-5

- Katz, Fred Emil (1993). Ordinary People and Extraordinary Evil, SUNY Press, ISBN 0-7914-1442-6;

- Katz, Fred Emil (2004). Confronting Evil, SUNY Press, ISBN 0-7914-6030-4.

- Neiman, Susan (2002). Evil in Modern Thought – An Alternative History of Philosophy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Oppenheimer, Paul (1996). Evil and the Demonic: A New Theory of Monstrous Behavior. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-6193-9.

- Shermer, M. (2004). The Science of Good & Evil. New York: Time Books. ISBN 0-8050-7520-8

- Steven Mintz; John Stauffer, eds. (2007). The Problem of Evil: Slavery, Freedom, and the Ambiguities of American Reform. University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 978-1-55849-570-8.

- Stapley, A.B. & Elder Delbert L. (1975). Using Our Free Agency. Ensign May: 21

- Stark, Ryan (2009). Rhetoric, Science, and Magic in Seventeenth-Century England. Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press. 115–45.

- Vetlesen, Arne Johan (2005). Evil and Human Agency – Understanding Collective Evildoing New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85694-2

- Wilson, William McF., Julian N. Hartt (2004). Farrer's Theodicy. In David Hein and Edward Hugh Henderson (eds), Captured by the Crucified: The Practical Theology of Austin Farrer. New York and London: T & T Clark / Continuum. ISBN 0-567-02510-1

External links

- Evil on In Our Time at the BBC

- "Concept of Evl" entry by Todd Calder in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Good and Evil in (Ultra Orthodox) Judaism

- ABC News: Looking for Evil in Everyday Life

- Psychology Today: Indexing Evil

- Booknotes interview with Lance Morrow on Evil: An Investigation, October 19, 2003.

- "Good and Evil", BBC Radio 4 discussion with Leszek Kolakowski and Galen Strawson (In Our Time, Apr. 1, 1999).

- "Evil", BBC Radio 4 discussion with Jones Erwin, Stefan Mullhall and Margaret Atkins (In Our Time, May 3, 2001)