Makkhali Gosala

Makkhali Gosala | |

|---|---|

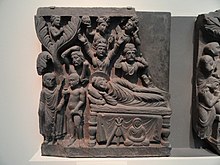

On the left: Mahakashyapa meets an Ajivika and learns of the Parinirvana[1] | |

| Personal | |

| Religion | Founder of Ajivika |

| The views of six śramaṇa in the Pāli Canon (based on the Buddhist text Sāmaññaphala Sutta1) | |

| Śramaṇa | view (diṭṭhi)1 |

| Pūraṇa Kassapa | Amoralism: denies any reward or punishment for either good or bad deeds. |

| Makkhali Gośāla (Ājīvika) | Niyativāda (Fatalism): we are powerless; suffering is pre-destined. |

| Ajita Kesakambalī (Lokāyata) | Materialism: live happily; with death, all is annihilated. |

| Pakudha Kaccāyana | Sassatavāda (Eternalism): Matter, pleasure, pain and the soul are eternal and do not interact. |

| Nigaṇṭha Nātaputta (Jainism) | Restraint: be endowed with, cleansed by and suffused with the avoidance of all evil.2 |

| Sañjaya Belaṭṭhiputta (Ajñana) | Agnosticism: "I don't think so. I don't think in that way or otherwise. I don't think not or not not." Suspension of judgement. |

| Notes: | 1. DN 2 (Thanissaro, 1997; Walshe, 1995, pp. 91-109). 2. DN-a (Ñāṇamoli & Bodhi, 1995, pp. 1258-59, n. 585). |

Makkhali Gosala (Pāli; BHS: Maskarin Gośāla; Jain Prakrit sources: Gosala Mankhaliputta) or Manthaliputra Goshalak (b. about 523 BCE) was an ascetic ajivika teacher of ancient India. He was a contemporary of Gautama Buddha, the founder of Buddhism, and of Mahavira, the last and 24th Tirthankara of Jainism.

Sources[edit]

Details about Gosala's life are sparse. All of the available information about Gosala and about the Ājīvika movement generally comes from Buddhist and Jain sources. As Gosala's teachings appear to have been rivals of those of the Buddhist and Jain leaders of his day, this information is regarded by most scholars as being overtly influenced and coloured by sectarian hostilities.

Two primary sources describe Gosala's life and teaching: the Jain Bhagavati Sutra, and Buddhaghosa's commentary on the Buddhist Sammannaphala Sutta.[2]: 35 The Bhagavati Sutra goes into detail about the career of Makkhali Gosala and his relationship with Mahavira; the Sammannaphala Sutra itself mentions Makkhali in passing as one of six leading teachers of philosophy of the Buddha's day, and Buddhaghosa's commentary provides additional details about his life and teaching.

With regards to his early years, it is related in the Bhagavati[3] that he was born in the settlement Saravana, in the vicinity apparently of the city of Savatthi.(Shravasti, Uttar Pradesh)[4] He came of low parentage. His father was a Mankhali, i . e., a mendicant who earned his livelihood by showing a picture which he carried in his hand. Once on his wanderings Mankhali came to Saravana and failing to obtain any other shelter, he took refuge for the rainy season in the cowshed(Gosala) of a wealthy Brahman Gobahula, where his wife Bhadda brought forth a son who became famous as Gosala Mankhaliputta. When grown up, he adopted the profession of his father, that is, of a Mankhali. In his wanderings, Gosala happened to meet the young ascetic Mahavira in Nalanda.

The name 'Gosala' literally means 'cow shed', and both the Bhagavati Sutra and Buddhaghosa claim that Gosala was so named because he was born in a cow shed, his parents being unable to find more suitable lodgings in the village of Saravana.[2]: 36 The Bhagavati Sutra reports that Gosala went on to follow his father's profession, becoming a mankha. Meanwhile, Buddhaghosa claims that Gosala was born into slavery, and became a naked ascetic after fleeing from his irate master, who managed to grab hold of Gosala's garment and disrobe him as he fled.[2]: 37 While it is possible that the broad outlines of Gosala's birth story or early life are correct—that he was born into poverty in a cowshed—it may be equally likely that these versions of his early life were concocted by Buddhist and Jain partisans to bring a rival teacher into disrepute.[2]: 38

The philosopher's true name seems to have been Maskarin, the Jaina Prakrit form of which is Mankhali and the Pāli form Makkhali. "Maskarin" is explained by Pāninī (VI.i.154) as "one who carries a bamboo staff" (maskara). A Maskarin is also known as Ekadandin. According to Patañjali (Mahābhāsya iii.96), the name indicates a School of Wanderers who were called Maskarins, not so much because they carried a bamboo staff as because they taught "Don't perform actions, don't perform actions, quietism (alone) is desirable to you". The Maskarins were thus fatalists or determinists.[5]

Makkhali Gosala and Mahavira[edit]

The Bhagavati Sutra states that Gosala became Mahavira's disciple three years after the start of Mahavira's asceticism, and travelled with him for the next six years.[6][2]: 40

A commentary to the Jain Avasyaka Sutra provides details of these six years of association, many of them reflecting poorly on Gosala- another likely indication of sectarian bias.[2]: 41–45 Several incidents in the narrative show Mahavira making predictions that then come true, despite Gosala's repeated attempts to foil them. These incidents were likely included in the narrative to provide motivation for Gosala's later belief in the inevitability of fate.[2]: 40 Some of these incidents may in fact have been adapted from Ajivika sources but recast by Jaina chroniclers.[2]: 46

Another possible adaptation of an Ajivika story is found in Mahavira's explanation of the end of the association between himself and Gosala, recorded in the Bhagavati Sutra.[2]: 48–49 On coming to a plant by the roadside, Gosala asked Mahavira what the fate of the plant and its seeds would be. Mahavira stated that the plant would grow to fruition, and the seed pods would grow into new plants. Determined to foil his master's prediction, Gosala returned to the plant at night and uprooted it. Later, a sudden rain shower caused the plant to revive and re-root itself. Upon approaching the plant again later, Gosala claimed to Mahavira that he would find his prophecy to have been foiled. Instead, it was found that the plant and its seeds had developed exactly as predicted by Mahavira. Gosala was so impressed by the reanimation of the plant that he became convinced that all living things were capable of such reanimation. The terms used in the story of the Bhagavati Sutra for reanimation mimic a technical term for reanimation of the dead that is also found elsewhere in Ajivika doctrine.[2]: 48–49 Mahavira disagreed with this thesis, and this seems to have been the cause of the separation of the two ascetics. Mahavira is, however, later depicted as having rescued Gosala from an attack by an enraged renunciant using magical powers acquired through the practice of austerities; this is claimed to motivate Gosala's pursuit of the same sort of magical powers.[2]: 49–50

Death[edit]

A. L. Basham dates the death of Gosala in 484 BCE on the basis of Mahavamsa.[7]

In literature[edit]

Gosala appears briefly as a "cameo" character in the 1981 Gore Vidal novel Creation, a fictional account of the Persian Wars of the 5th century BCE, told from the perspective of a widely travelled Persian diplomat, Cyrus Spitama, who is depicted as the grandson of Zoroaster and boyhood friend of Xerxes I. In early adulthood, thanks to his facility with languages, Cyrus is appointed by King Darius I as the Persian ambassador to the kingdoms of India. While travelling across the Subcontinent, Cyrus stops at the city of Mathura, where he is accosted by the Jain sage, who lectures Cyrus about his views on the inevitability of fate, and his disagreements with Mahavira.[8]

'Khanti Kikatia' is a novel focused on the life of Makkhali Gosala, written by Ashwini Kumar Pankaj in the Magahi language.[9]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Marianne Yaldiz, Herbert Härtel, Along the Ancient Silk Routes: Central Asian Art from the West Berlin State Museums; an Exhibition Lent by the Museum Für Indische Kunst, Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1982 p. 78

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Basham, A.L. (2002). History and Doctrines of the Ājīvikas. Delhi, India: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN 81-208-1204-2.

- ^ https://www.jainfoundation.in/JAINLIBRARY/books/agam_05_ang_05_bhagvati_vyakhya_prajnapti_sutra_part01_002130_hr.pdf

- ^ https://www.rarebooksocietyofindia.org/book_archive/196174216674_10153031903361675.pdf

- ^ Barua 1920, p. 12.

- ^ Dundas 2002, p. 29.

- ^ Kailash Chand Jain 1991, p. 75.

- ^ Gore Vidal, Creation: A Novel (Random House, 1981), pp.189-192

- ^ Ashwini Kumar Pankaj, Khanti Kikatia: A Novel based on life and thought of Makkhali Goasala (Pyara Kerketta Foundation, 2018)

Sources[edit]

- Barua, B.M. (1920). The Ajivikas. University of Calcutta.

- Basham, A.L. (2002) [1951]. History and Doctrines of the Ājīvikas (2nd ed.). Delhi, India: Moltilal Banarsidass Publications. ISBN 81-208-1204-2. originally published by Luzac & Company Ltd., London, 1951.

- Jain, Kailash Chand (1991), Lord Mahāvīra and His Times, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0805-8

- Ñāṇamoli, Bhikkhu (trans.) and Bodhi, Bhikkhu (ed.) (2001). The Middle-Length Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Majjhima Nikāya. Boston: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-072-X.

- Thanissaro Bhikkhu (trans.) (1997). Samaññaphala Sutta: The Fruits of the Contemplative Life (DN 2). Available on-line at http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/dn/dn.02.0.than.html.

- Walshe, Maurice O'Connell (trans.) (1995). The Long Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Dīgha Nikāya. Somerville: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-103-3.

- Dundas, Paul (2002) [1992], The Jains (Second ed.), Routledge, ISBN 0-415-26605-X

External links[edit]

- 풀라나 카사파 무도덕론, 도덕부정론: 선행도 악행도 없고, 선악 어떠한 보상도 존재하지 않는다.

- 맥칼리 고사라 ( 아지비카교 ) 운명 결정론 (숙명론): 자기의 의지에 의한 행위는 없고, 일체는 미리 결정되어 있어 정해진 기간 유전하는 정이다.

- 아지타 케이사 캄버린 ( 순세파 ) 유물론 , 감각론 , 쾌락주의 : 사람은 4대로 이루어져 죽으면 흩어져 아무것도 남지 않는다. 선악 어떠한 행위의 보상도 없다고 해, 현세의 쾌락·향악만을 설명한다.

- 박다 카차야나 ( 상주론자 ) 요소 집합설 : 사람은 땅·물·화·바람의 4원소와 고·락·생명(영혼)의 7개의 요소의 집합으로 구성되어 있으며, 그들은 불변 부동으로 상호의 영향은 없다.

- 마하빌라 ( 자이나교 ) 상대주의, 고행주의, 요소 실재설 : 영혼은 영원불멸의 실체이며, 거지·고행생활에서 업의 더러움을 떨어뜨리고 涅槃를 목표로 한다.

- 산자야 베라티푸타 - 불가지론 , 회의론 : 진리를 그대로 인식하고 설명하는 것은 불가능하다고 한다. 판단의 유보.

- 표이야기편역사

- ↑ a b 미즈노 히로모토 「증보 개정 파리어 사전」춘추사, 2013년 3월, 증보 개정판 제4쇄, p.334

- ^ a b DN 2 (Thanissaro, 1997; Walshe, 1995, pp. 91-109).

- ↑ Area de “세계 종교사 3”(2000) p.124

- ↑ 일반에는 기원전 486년설 (중성점 기설)이 채용되지만, 우이 백수 는 기원전 386년설 을 채택하고 있다.

- ↑ Area de “세계 종교사 3” 2000년, p.125

- ↑ 나카무라 (1968)

- ^ 『사만냐 파라·스타』보다. 에리어 데 「세계 종교사 3」2000년, p.125

- ^ 대劫 (마하 칼파, Mahakalpa )는 인도에서 매우 오래된 우주 론적 시간 단위. 성주괴공의 1사이클로 80회의劫(中劫)로 이루어진다.

- ^ 석가는, 이 철저한 결정론을 범죄적인 것으로 간주해, 동시대인 속에서 고사라를 가장 격렬하게 공격했다. 에리어 데 「세계 종교사 3」2000년, p.125

- ^ 「청정한 것을 마신다」라는 의미의 금식 .

- ↑ 마루이 히로 「고행」 「남아시아를 아는 사전」 1992년, p.199.

- ^ 어원의 아지바는 「생활 방식, 혹은 존재의 종류를 포기하는 것」이라고 설명되지만 「생명처럼 영원하다」라는 표현에서 파생된 것으로도 알려져 있다. 에리어데 「세계 종교사 3」(2000) 「문헌 해제」보다.

- ↑ Area de “세계 종교사 3”(2000) p.126