NOBEL PRIZE

Why Tanzanian writer Abdulrazak Gurnah’s Nobel Prize for Literature is important

The 73-year-old writer represents both a post-colonial African sensibility and an Islamic interiority.

Bhakti Shringarpure

Oct 09, 2021 · 08:30 am

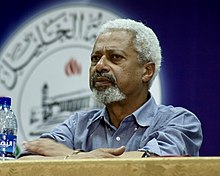

Abdulrazak Gurnah. | Henry Nicholls / Reuters

Abdulrazak Gurnah. | Henry Nicholls / ReutersThe Swedes have succeeded once again in surprising everyone with a stealthy pick for this year’s Nobel Prize in Literature. Abdulrazak Gurnah (b 1948) was announced as the winner this year and he is only the sixth writer from the African continent to receive this prestigious prize. For cynics, gamblers, bookworms and African literature connoisseurs, this news comes like a breath of fresh air. Gurnah’s own surprise at having received the prize illustrates just how little love is given to the vast, diverse and dazzling range of literature from Africa.

In fact, this will be Nobel prize magic at its best: suddenly, a relatively unknown novelist will become a household name and Gurnah’s books, which are difficult to access outside of the UK and East Africa, will sell widely.

Gurnah will be celebrated as a Tanzanian writer and thus it is imperative to immediately highlight his tangled and complex identity. Gurnah is really from Zanzibar, an autonomous group of islands in the Indian ocean, which merged with the mainland upon independence from the British in the sixties under the name Tanzania.

However, relationship with the mainland has always been culturally and politically fraught, and Gurnah has admitted that he moved to the UK in the sixties in order to escape state terror against Arabs in Zanzibar. Only six months ago, Samia Suluhu Hassan was sworn into office as Tanzania’s president, the first woman and the first leader in this position from Zanzibar. Gurnah and Hassan both provide us an opportunity to reflect on the silenced histories of “small places” that suffer the impact of colonialism but often remain subjugated by the nation in power as well.

Gurnah also belongs to the group referred to as Black British writers, comprised of people who migrated to the UK from previously colonised regions, and who tend to explore themes of migration and assimilation. Having arrived in the UK without a visa, Gurnah’s writing with its focus on memory and the impossibility of finding belonging is considered an important contribution to this tradition.

Melancholy and a crippling alienation is at the heart of most of Gurnah’s work. He has said that “the loneliness, the estrangement became fertile ground for reflection and led me to writing fiction,” referring to his experiences of migrating to the UK and feeling shocked at the overt racism he encountered.

Today, writers like Leila Aboulela from Sudan, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Teju Cole from Nigeria, and NoViolet Bulawayo from Zimbabwe are far better known for their focus on the themes of migration. But it is Gurnah who must be credited for being one of first writers to articulate the experiences of the journey from Africa to the West.

Postcolonial novelist

Gurnah was almost forty years old when he published his first novel, The Memory of Departure (1987), and despite having lived in the UK for many years and having obtained a PhD in literature by then, it appeared to come from a place of having left home. “I was still leaving,” he told Razia Iqbal in an interview only two years ago.

This first novel had, in fact, been completed over a decade ago but was rejected by the Heinemann African Writers series, which, Gurnah later realised, was because his work was not easy to locate as African or British or diasporic. A few years later, it was his fourth novel, Paradise, which was shortlisted for the Booker Prize, and it was then that Gurnah’s work began penetrating a wider readership and garner critical interest.

Gurnah’s works are not necessarily easy reading, with characters that are often unmoored and weighed down by loss. Protagonists grappling with living on the margins of society, doomed inter-racial love, and a claustrophobic aura of displacement pervades his works. Places are often not named and narrative resolutions are far too few.

There is also a rich intertextuality; references to a web of literary texts that make it intimidating for readers to wade through. Virginia Woolf’s simple but evocative phrase is a great way to describe Gurnah’s writing: “Memory runs her needle in and out, up and down, hither and thither.” His novels, while being cerebral, also tend to be deeply sensory and masterfully evoke vanished worlds.

The Nobel committee spoke of Gurnah’s contribution to postcolonial literature and his exploration of the pernicious effects of colonialism. Certainly this is true, but it is far more generative to reflect on the unique prisms he brings to postcolonial studies. Gurnah’s work centres the ocean as a place from and through which histories, identities, relationships, intimacies and politics are brought into being. The vast yet under-explored Swahili coast is home to a rich amalgam of African, Asian and Arab heritages and it is these worlds that Gurnah maps in his novels.

“The sense of belonging to that Indian Ocean world, at least the part of it that I knew, which is largely an Islamic one which had been sort of incorporated into Islamic epistemology, even if you’re talking about India or Hindu cultures. So that’s one way of understanding, as I say,” he admitted to academic Tina Steiner. “But then these other things that are to do really with more complicated matters. It is the history of violence; it is a history of exploitation, of people coming from elsewhere, particularly the part of the East African Coast that I come from.” It is, of course, no surprise then that Gurnah’s work presents an extraordinary challenge and a provocation to typical ways of reading and thinking about postcolonial literature.

A second important consideration is the way in which Gurnah narrates a lyrical Muslim interiority. Gurnah doesn’t necessarily write or ponder about Islam specifically but given the relentless maligning of Muslim people the world over and with the effects of the War on Terror still looming large on this population, it is crucial to acknowledge that Gurnah’s novels give readers access to an array of Muslim characters fleshed out with care, humanity and complexity.

An African laureate

There is the elephant in the Nobel room this year: the much debated fate of Kenyan literary giant Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o who, once again, did not win, while the work of a different East African writer was suddenly recognised. African literature in the English speaking world is dominated by writing from South Africa and Nigeria. An easy indicator is the fact that two South African writers, JM Coetzee and Nadine Gordimer, have already won the Nobel Prize in addition to Wole Soyinka from Nigeria.

Ngugi writes plenty in English but has been a committed and vocal advocate for keeping native languages alive and has produced works in his mother tongue, Gĩkũyũ. Like Kenya, Tanzania is also a country where Swahili culture, literature and education remain vibrantly alive.

An irony slowly comes into view: Gurnah writes in English even though it is inflected with Swahili and even though Swahili is his mother tongue. The Nobel, it seems, has once again chosen to reward the primacy of English language writing on the continent and has snubbed the one writer who has tirelessly fought against that domination.

But if the ubiquitous idea of “literary merit” is the only thing that counts, as the Nobel committee has been known to say, there is no one more deserving of this acclaim and prestige than Abdulrazak Gurnah.

Bhakti Shringarpure is a writer and academic. She is the editor of Warscapes magazine and the co-founder of the Radical Books Collective. Twitter @bhakti_shringa.

Abdulrazak Gurnah

Abdulrazak Gurnah | |

|---|---|

Gurnah in May 2009 | |

| Born | 20 December 1948 Sultanate of Zanzibar |

| Occupation | Novelist, professor |

| Language | English |

| Education | Canterbury Christ Church University (BA) University of Kent (MA, PhD) |

| Notable works |

|

| Notable awards | Nobel Prize in Literature (2021) |

| Website | |

| rcwlitagency.com | |

Abdulrazak Gurnah FRSL (born 20 December 1948) is a Tanzanian-born novelist and academic who is based in the United Kingdom. He was born in the Sultanate of Zanzibar and moved to the United Kingdom in the 1960s as a refugee during the Zanzibar Revolution.[1] His novels include Paradise (1994), which was shortlisted for both the Booker and the Whitbread Prize; Desertion (2005); and By the Sea (2001), which was longlisted for the Booker and shortlisted for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize.

Gurnah was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2021 "for his uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fates of the refugee in the gulf between cultures and continents".[1][2][3] He is Emeritus Professor of English and Postcolonial Literatures at the University of Kent.[4]

Early life and education[edit]

Abdulrazak Gurnah was born on 20 December 1948[5] in the Sultanate of Zanzibar, which is now part of present-day Tanzania.[6] He left the island at the age of 18 following the overthrow of the ruling Arab elite in the Zanzibar Revolution,[3][1] arriving in England in 1968 as a refugee. He is of Arab heritage.[7] Gurnah has been quoted saying, "I came to England when these words, such as asylum-seeker, were not quite the same – more people are struggling and running from terror states."[1][8]

He initially studied at Christ Church College, Canterbury, whose degrees were at the time awarded by the University of London.[9] He then moved to the University of Kent, where he earned his PhD, with a thesis titled Criteria in the Criticism of West African Fiction,[10] in 1982.[6]

Career[edit]

From 1980 to 1983, Gurnah lectured at Bayero University Kano in Nigeria. He went on to become a professor of English and postcolonial literature at the University of Kent, where he taught until his retirement[3][11] in 2017, and where he is now professor emeritus of English and postcolonial literatures.[12]

Writing[edit]

Alongside his work in academia, Gurnah is a writer and novelist. He is the author of many short stories, essays and ten novels.[13]

While his first language is Swahili, he has used English as his literary language. However, Gurnah integrates bits of Swahili, Arabic, and German throughout most of his writings. He has said that he had to push back against publishers to continue this practice, while they would have preferred to "italicize or Anglicize Swahili and Arabic references and phrases in his books."[11] Gurnah has criticized the practices in both British and American publishing which want to "make the alien seem alien" by marking 'foreign' terms and phrases with italics or by putting them in a glossary.[11]

Gurnah began writing out of homesickness during his 20s. He started with writing down thoughts in his diary, which turned into longer reflections about home; and eventually grew into writing fictional stories about other people. This created a habit of using writing as a tool to understand and record his experience of being a refugee, living in another land, and the feeling of being displaced. These initial stories eventually became Gurnah's first novel, Memory of Departure (1987), which he wrote alongside his Ph.D. dissertation. This first book set the stage for his ongoing exploration of the themes of "the lingering trauma of colonialism, war and displacement" throughout his subsequent novels, short stories and critical essays.[11]

Themes[edit]

Consistent themes run throughout Gurnah's writing. These include exile, displacement and belonging, alongside colonialism and broken promises on the part of the state. Most of his novels focus on telling stories about social and humanitarian issues, especially about war or crisis affected individuals living in the developing world that may not have the capability of telling their own stories to the world - or documenting their experiences. [14][15]

Much of Gurnah's work is set on the coast of East Africa,[16] and all but one of his novels' protagonists were born in Zanzibar.[17] Though Gurnah has not returned to live in Tanzania since he left at 18, he has said that his homeland "always asserts himself in his imagination, even when he deliberately tries to set his stories elsewhere."[11]

Literary critic Bruce King posits that Gurnah's novels place East African protagonists in their broader international context, observing that in Gurnah's fiction "Africans have always been part of the larger, changing world".[18] According to King, Gurnah's characters are often uprooted, alienated, unwanted and therefore are, or feel, resentful victims".[18] Felicity Hand suggests that Gurnah's novels Admiring Silence (1996), By the Sea (2001), and Desertion (2005) all concern "the alienation and loneliness that emigration can produce and the soul-searching questions it gives rise to about fragmented identities and the very meaning of 'home'."[19] She observes that Gurnah's characters typically do not succeed abroad following their migration, using irony and humour to respond to their situation.[20]

Novelist Maaza Mengiste has described Gurnah's works, saying: "He has written work that is absolutely unflinching and yet at the same time completely compassionate and full of heart for people of East Africa [...] He is writing stories that are often quiet stories of people who aren’t heard, but there’s an insistence there that we listen."[11]

Other work[edit]

Gurnah edited two volumes of Essays on African Writing and has published articles on a number of contemporary postcolonial writers, including V. S. Naipaul, Salman Rushdie and Zoë Wicomb. He is the editor of A Companion to Salman Rushdie (Cambridge University Press, 2007). He has been a contributing editor of Wasafiri magazine since 1987.[21] He has been a judge for awards including the Caine Prize for African Writing,[22] the Booker Prize.[23] and the RSL Literature Matters Awards.[24]

Awards and honours[edit]

Gurnah's 2004 novel Paradise was shortlisted for the Booker, the Whitbread and the Writers' Guild Prizes, as well as the ALOA Prize for the best Danish translation.[25] His novel By the Sea (2001) was longlisted for the Booker and shortlisted for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize,[25] while Desertion (2005) was shortlisted for the 2006 Commonwealth Writers' Prize.[25][26]

In 2006, Gurnah was elected a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature.[27] In 2007, he won the RFI Témoin du Monde ("Witness of the world") award in France for By the Sea.[28]

On 7 October 2021, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for 2021 "for his uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fates of the refugee in the gulf between cultures and continents".[2][3][1] Gurnah was the first Black writer to receive the prize since 1993, and the first African writer since 2007. While author Giles Foden has called him "one of Africa's greatest living writers", prior to winning the prestigious award Gurnah's writing had not achieved the same commercial success of other Nobel winners.[11]

Personal life[edit]

Gurnah lives in Canterbury, England,[29] and has British citizenship.[30] He maintains close ties with Tanzania, where he still has family, and where he says he goes when he can: "I am from there. In my mind I live there."[31]

Writings[edit]

Novels[edit]

- Memory of Departure (1987)[32]

- Pilgrims Way (1988)[33]

- Dottie (1990)[34]

- Paradise (1994)[35] (shortlisted for the Booker Prize[36] and the Whitbread Prize[36])

- Admiring Silence (1996)[37]

- By the Sea (2001)[35] (longlisted for the Booker Prize[38] and shortlisted for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize)[38]

- Desertion (2005)[39]

- The Last Gift (2011)[40]

- Gravel Heart (2017)[41]

- Afterlives (2020)[42]

Short stories[edit]

- "Cages" (1984), in African Short Stories. Ed. by Chinua Achebe and Catherine Lynette Innes. Heinemann Educational Books. ISBN 9780435902704

- "Bossy" (1994), in African Rhapsody: Short Stories of the Contemporary African Experience. Ed. by Nadežda Obradović. Anchor Books. ISBN 9780385468169

- "Escort" (1996), in Wasafiri, vol. 11, no. 23, 44–48. doi:10.1080/02690059608589487

- "The Photograph of the Prince" (2012), in Road Stories: New Writing Inspired by Exhibition Road. Ed. by Mary Morris. Royal Borough of Kensington & Chelsea, London. ISBN 9780954984847

- "My Mother Lived on a Farm in Africa" (2006), in NW 14: The Anthology of New Writing, Volume 14, selected by Lavinia Greenlaw and Helon Habila, London: Granta Books[43]

- "The Arriver's Tale", Refugee Tales (2016)[44]

- "The Stateless Person's Tale", Refugee Tales III (2019)[45]

Essays, criticism, and non-fiction[edit]

- "Matigari: A Tract of Resistance." In: Research in African Literatures, vol. 22, no. 4, Indiana University Press, 1991, pp. 169–72. JSTOR 3820366.

- "Imagining the Postcolonial Writer." In: Reading the 'New' Literatures in a Postcolonial Era. Ed. by Susheila Nasta. D. S. Brewer, Cambridge 2000. ISBN 9780859916011.

- "The Wood of the Moon." In: Transition, no. 88, Indiana University Press, Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard University, 2001, pp. 88–113. JSTOR 3137495.

- "Themes and Structures in Midnight's Children". In: The Cambridge Companion to Salman Rushdie. Ed. by Abdulrazak Gurnah. Cambridge University Press, 2007. ISBN 9780521609951.[46]

- "Mid Morning Moon". In: Wasafiri (3 May 2011), vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 25–29. doi:10.1080/02690055.2011.557532.

- Abdulrazak Gurnah (July 2011). "The Urge to Nowhere: Wicomb and Cosmopolitanism". Safundi. 12 (3–4): 261–275. doi:10.1080/17533171.2011.586828. ISSN 1543-1304. Wikidata Q108824246.

- "Learning to Read". In: Matatu, no. 46, 2015, pp. 23–32, 268.

As editor[edit]

- Essays on African Writing (Pearson Education Limited, 1995)

- A Companion to Salman Rushdie (Cambridge University Press, 2007)

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e "Nobel Literature Prize 2021: Abdulrazak Gurnah named winner". BBC News. 7 October 2021. Archived from the original on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ a b "The Nobel Prize in Literature 2021". NobelPrize.org. 7 October 2021. Archived from the original on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ a b c d Flood, Alison (7 October 2021). "Abdulrazak Gurnah wins the 2021 Nobel prize in literature". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ "Professor Abdulrazak Gurnah". University of Kent | School of English. 7 October 2021. Archived from the original on 8 October 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ Loimeier, Manfred (30 August 2016). "Gurnah, Abdulrazak". In Ruckaberle, Axel (ed.). Metzler Lexikon Weltliteratur: Band 2: G–M (in German). Springer. pp. 82–83. ISBN 978-3-476-00129-0. Archived from the original on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ a b King, Bruce (2004). Bate, Jonathan; Burrow, Colin (eds.). The Oxford English Literary History. 13. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 336. ISBN 978-0-19-957538-1. OCLC 49564874.

- ^ "Abdulrazak Gurnah wins the Nobel prize in literature for 2021". The Economist. 7 October 2021.

- ^ Prono, Luca (2005). "Abdulrazak Gurnah – Literature". British Council. Archived from the original on 3 August 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ Hand, Felicity. "Abdulrazak Gurnah (1948–)". The Literary Encyclopedia (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 June 2018. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ Erskine, Elizabeth, ed. (1989). Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature for 1986. 61. W. S. Maney & Son. p. 588. ISBN 0-947623-30-2. ISSN 0066-3786.

- ^ a b c d e f g Alter, Alexandra; Marshall, Alex (7 October 2021). "Abdulrazak Gurnah Is Awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ Attree, Lizzy (7 October 2021). "Nobel Prize winner Abdulrazak Gurnah: An introduction to the man and his writing". The World. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- ^ Johnson, Simon; Pawlak, Justyna (8 October 2021). "Tanzanian novelist Gurnah wins 2021 Nobel for depicting impact of colonialism, migration". Reuters. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

- ^ Mengiste, Maaza (8 October 2021). "Abdulrazak Gurnah: where to start with the Nobel prize winner". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ Kaigai, Ezekiel Kimani (2014) "Encountering Strange Lands: Migrant Texture in Abdulrazak Gurnah's Fiction". Stellenbosch University. Archived from the original on 10 October 2021. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- ^ Lavery 2013, p. 118.

- ^ Bosman, Sean James (26 August 2021). "Abdulrazak Gurnah". Rejection of Victimhood in Literature by Abdulrazak Gurnah, Viet Thanh Nguyen, and Luis Alberto Urrea. Brill. pp. 36–72. doi:10.1163/9789004469006_003. ISBN 978-90-04-46900-6.

- ^ a b King 2006, p. 86.

- ^ Hand 2012, p. 39.

- ^ Hand 2012, p. 56.

- ^ "People | Abdulrazak Gurnah". Wasafiri. Archived from the original on 3 August 2019. Retrieved 7 October2021.

- ^ "Kenyan wins African writing prize". BBC News. 16 July 2002.

- ^ "Abdulrazak Gurnah on being appointed as Man Booker Prize judge". University of Kent. 26 October 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ "RSL Literature Matters Awards 2019". The Royal Society of Literature. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- ^ a b c "Abdulrazak Gurnah: Influencing policymakers, cultural providers, curricula, and the reading public worldwide via new imaginings of empire and postcoloniality". REF 2014 | Impact Case Studies. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- ^ "We Congratulate 2021 Nobel Laureate for Literature Abdulrazak Gurnah". The Authors'Guild. 7 October 2021. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- ^ "Abdulrazak Gurnah". Royal Society of Literature. Archived from the original on 10 October 2020. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ Fruchon-Toussaint, Catherine (8 March 2007). "Abdulrazak Gurnah, Prix RFI Témoin du Monde 2007". RFI (in French). Archived from the original on 14 March 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ Shariatmadari, David (11 October 2021). "'I could do with more readers!' – Abdulrazak Gurnah on winning the Nobel prize for literature". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

- ^ "Can the Nobel Prize 'revitalize' African literature?". Deutsche Welle. 8 October 2021. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- ^ Awami, Sammy (9 October 2021). "In Tanzania, Gurnah's Nobel Prize win sparks both joy and debate". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- ^ Hand, Felicity (15 March 2015). "Searching for New Scripts: Gender Roles in Memory of Departure". Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction. 56 (2): 223–240. doi:10.1080/00111619.2014.884991. ISSN 0011-1619. S2CID 144088925. Archived from the original on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ Mirmotahari, Emad (May 2013). "From Black Britain to Black Internationalism in Abdulrazak Gurnah's Pilgrims Way". English Studies in Africa. 56 (1): 17–27. doi:10.1080/00138398.2013.780679. ISSN 0013-8398. S2CID 154423559. Archived from the original on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ Lewis, Simon (May 2013). "Postmodern Materialism in Abdulrazak Gurnah's Dottie : Intertextuality as Ideological Critique of Englishness". English Studies in Africa. 56 (1): 39–50. doi:10.1080/00138398.2013.780680. ISSN 0013-8398. S2CID 145731880.

- ^ a b Kohler, Sophy (4 May 2017). "'The spice of life': trade, storytelling and movement in Paradise and By the Sea by Abdulrazak Gurnah". Social Dynamics. 43 (2): 274–285. doi:10.1080/02533952.2017.1364471. ISSN 0253-3952. S2CID 149236009.

- ^ a b "Nobel Prize in Literature 2021: Abdulrazak Gurnah honoured". The Irish Times. 7 October 2021. Archivedfrom the original on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ Olaussen, Maria (May 2013). "The Submerged History of the Indian Ocean in Admiring Silence". English Studies in Africa. 56 (1): 65–77. doi:10.1080/00138398.2013.780682. ISSN 0013-8398. S2CID 162203810.

- ^ a b "Abdulrazak Gurnah". Booker Prize. Archived from the original on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 7 October2021.

- ^ Mars-Jones, Adam (15 May 2005). "It was all going so well". The Observer. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ Kaigai, Kimani (May 2013). "At the Margins: Silences in Abdulrazak Gurnah's Admiring Silence and The Last Gift". English Studies in Africa. 56 (1): 128–140. doi:10.1080/00138398.2013.780688. ISSN 0013-8398. S2CID 143867462.

- ^ Bosman, Sean James (3 July 2021). "'A Fiction to Mock the Cuckold': Reinvigorating the Cliché Figure of the Cuckold in Abdulrazak Gurnah's By the Sea (2001) and Gravel Heart (2017)". Eastern African Literary and Cultural Studies. 7 (3): 176–188. doi:10.1080/23277408.2020.1849907. ISSN 2327-7408. S2CID 233624331.

- ^ Mengiste, Maaza (30 September 2020). "Afterlives by Abdulrazak Gurnah review – living through colonialism". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 September 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ "Biobibliographical notes". Nobel Prize. Archived from the original on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 7 October2021.

- ^ "Refugee Tales – Comma Press". commapress.co.uk. Archived from the original on 28 May 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ "Refugee Tales: Volume III – Comma Press". commapress.co.uk. Archived from the original on 10 May 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ Gurnah, Abdulrazak, "7 – Themes and structures in Midnight's Children", in Gurnah (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Salman Rushdie, Cambridge University Press, 28 November 2007.

Sources[edit]

- Hand, Felicity (2012). "Becoming Foreign: Tropes of Migrant Identity in Three Novels by Abdulrazak Gurnah". In Sell, Jonathan P. A. (ed.). Metaphor and Diaspora in Contemporary Writing. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 39–58. doi:10.1057/9780230358454_3. ISBN 978-1-349-33956-3.

- King, Bruce (2006). "Abdulrazak Gurnah and Hanif Kureishi: Failed Revolutions". In Acheson, James; Ross, Sarah C.E. (eds.). The Contemporary British Novel Since 1980. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 85–94. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-73717-8_8. ISBN 978-1-349-73717-8. OCLC 1104713636.

- Lavery, Charné (May 2013). "White-washed Minarets and Slimy Gutters: Abdulrazak Gurnah, Narrative Form and Indian Ocean Space". English Studies in Africa. 56 (1): 117–127. doi:10.1080/00138398.2013.780686. ISSN 0013-8398. S2CID 143927840.

Further reading[edit]

- Breitinger, Eckhard. "Gurnah, Abdulrazak S". Contemporary Novelists.

- Jones, Nisha (2005). "Abdulrazak Gurnah in conversation". Wasafiri, 20:46, 37–42. doi:10.1080/02690050508589982.

- Palmisano, Joseph M., ed. (2007). "Gurnah, Abdulrazak S.". Contemporary Authors. 153. Gale. pp. 134–136. ISBN 978-1-4144-1017-3. ISSN 0275-7176. OCLC 507351992.

- Whyte, Philip (2019). "East Africa in Postcolonial Fiction: History and Stories in Abdulrazak Gurnah's Paradise". In Noack, Stefan; de Gemeaux, Christine; Puschner, Uwe (eds.). Deutsch-Ostafrika: Dynamiken europäischer Kulturkontakte und Erfahrungshorizonte im kolonialen Raum. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3-631-77497-7.

- Whyte, Philip: Heritage as Nightmare: The Novels of Abdulrazak Gurnah", in: Commonwealth 27 (2004), no. 1:11-18.

External links[edit]

Abdulrazak Gurnah on Nobelprize.org

============================

Works by Abdulrazak Gurnah

Why the work of Abdulrazak Gurnah, the champion of heartbreak, stands out for me

October 14, 2021 7.25pm AEDT

Author

Fawzia Mustafa

Emerita Professor of English, Comparative Literature, African American and African Studies and Women's, Gender and Sexuality Studies, Fordham University

Disclosure statement

Fawzia Mustafa does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Abdulrazak Gurnah, the Tanzanian winner of the 2021 Nobel Prize for Literature, has some well-deserved seniority within the ever growing ranks of East African writers. He published his first novel, Memories of Departure, in 1987, and nine more since then. Among those, Paradise (1994), was short-listed for both the Booker Prize and the Whitbread Award. Yet another, By the Sea (2001), was long-listed for the Booker Prize and short-listed for the LA Times Book award.

Born in Zanzibar in 1948, Gurnah is also an accomplished scholar of African literature. Until his retirement recently, he was a professor at the University of Canterbury, in the UK. One crucial aspect of his biography remains his forced migration from Zanzibar to the UK in 1968, amid the turmoil following the 1964 revolution on the island. The trauma of that experience has fed much of his literary imagination and provided a wellspring for his novels of displacement and loss.

The East African region is rich with writers going back to the first post-independence generation. A random sampling of the first Anglophone generation from the three East African nations includes Uganda’s Okot p’Bitek, who translated his own work into English. Grace Ogot and Ngugi wa Thiongo from Kenya and Peter Palangyo and Gabriel Ruhambika of Tanzania also make the list.

More recently, a new generation of writers has obviously emerged. Again, a random sampling include millennials such as the late Binyavanga Wainaina (Kenya), Moses Isegawa (Uganda), and the Ethiopian Dinaw Mengetsu in his Uganda-based novel, All Our Names (2014). Add to these Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor (Kenya) who, in The Dragonfly Sea (2019), has recently used the Indian Ocean region and the East African littoral setting revisted by Gurnah in many of his novels.

Get your news from people who know what they’re talking about.

The generational and political transition necessarily reflects the different historical worlds within the region that are represented by East African writers. One writer who started out before Gurnah, for example, is Ngugi wa Thiongo, himself a perennial candidate for the Nobel.

In addition to Ngugi wa Thiongo, the Somali writer Nuruddin Farah has also been tipped frequently for the Nobel Prize. One may be justified to ask, why Gurnah over Ngugi or Farah? The Nobel Committee has often defied local knowledge, in the sense of choosing internationally recognised candidates rather than those more locally celebrated at home.

At the same time, writing “contests” don’t always measure literary talent helpfully. Recognition brings prestige, a larger readership, and more sales, but this impulsion remains part of the infrastructure of a non-local book industry that’s one of the pillars of old and new capitalisms, old and new colonialisms. Even in our digital age, who can afford books, or access, among the larger population? In many cases, only the elites.

Why Gurnah’s work is powerful

Nevertheless, I was very pleased to learn that Gurnah won this year. What stands out for me is Gurnah’s constant exploration of heartbreak. Certainly, he breaks mine. His novels delve deeply into family separation, endless betrayals of core familial relations, and the inexorable pull of the lost past. Each novel exposes another nuance, another hidden aspect, another self-inflicted betrayal.

The Last Gift (2011) harbours an extraordinary secret that is only disclosed at death. Desertion (2005) uses the trope of romance, over three generations, to show the inadequacy of love in the face of social change, be it political or cultural. Paradise (1994) possibly the best known of Gurnah’s novels, is also the first to evoke deep historical and cultural research. It brings home the multiple overlays of both Omani and European colonial power, control and oppression.

The other political landscapes of gender, sexuality, race and class are perhaps more finely tuned, and certainly more robust, in Gurnah’s work than, say, Ngugi and Farah. And this may also account for his good fortune, and within the world of world literature, this well-deserved prize.

For the last three-plus decades, along with M.G. Vassanji, Gurnah has been the Anglophone novelist mining the Tanzanian and Zanzibari – and by extension the Indian Ocean World literary landscape. This setting has underwritten Gurnah’s themes of (forced) migrations to the West, that which the Nobel Committee singled out in their announcement of Gurnah’s award.

At the same time, Gurnah is the one novelist who has always been able to also mine the local Kiswahili (including 19th-century coastal Arabic and Islamic) literary and historical traditions. These, along with colonial archives, both German and British, are incredibly rich but globally overlooked literary confluences.

Read more: Nobel Prize winner Abdulrazak Gurnah: an introduction to the man and his writing

Interestingly, Gurnah’s more recent work – such as Afterlives (2021) – has sometimes embraced a more overtly historical dimension of the region. Set at the height of German conquest, until their defeat in the first world war, the novel follows three figures, each of whom resemble in one way or another the protagonist of Paradise. The panoramic historical sweep of the first half of the novel is an authoritative account of the complexities of German colonial power up against extraordinary local resistance. At the same time, it makes visible the alternative choices that German colonialism provided to those already disenfranchised within older colonial systems and local oppressive regimes such as those of gender.

So, while his earlier work obsessively revisits migration and loss, it is almost always buffered or intersected with pretence, outright falsehoods and strategic deceit among his cast of protagonists. These are among the survival strategies born of migration, displacement and alienation.

Gurnah’s use of a form of dramatic irony has been extraordinary. This applies both at the level of familial conflict and separation and at the level of large-scale, brutal colonial social transformations, foreign and home-grown. In other words, the same kinds of circumstances that characterise the Zanzibar of Gurnah’s youth.

===

- Paradise (1994)?

- 구르나는 1987년 첫 장편 <출발의 기억>을 내놓은 이래 지금까지 10권의 장편소설과 다수의 단편을 발표했다. 그의 소설들에는 난민이 겪는 세계의 붕괴라는 주제가 일관되게 관류하고 있다.

- 부커상 최종후보에 올랐던 그의 네번째 장편 <낙원>(1994)이 대표작으로 꼽히는데, 1차 세계대전 당시 아프리카를 배경으로 삼은 이 소설은 조지프 콘래드의 소설 <암흑의 핵심>을 비틀어 쓴 작품으로 평가받는다.

- 그의 최근작인 대작 <내세>(2020)는 <낙원>이 끝나는 지점에서 시작된다. <낙원>과 마찬가지로 20세기 초를 무대로 삼아 <낙원>의 주인공 ‘유수프’를 연상시키는 청년 ‘함자’가 독일군으로 전쟁에 참전하고 그를 성적으로 착취하는 장교에게 의존하게 되는 과정을 그린다.