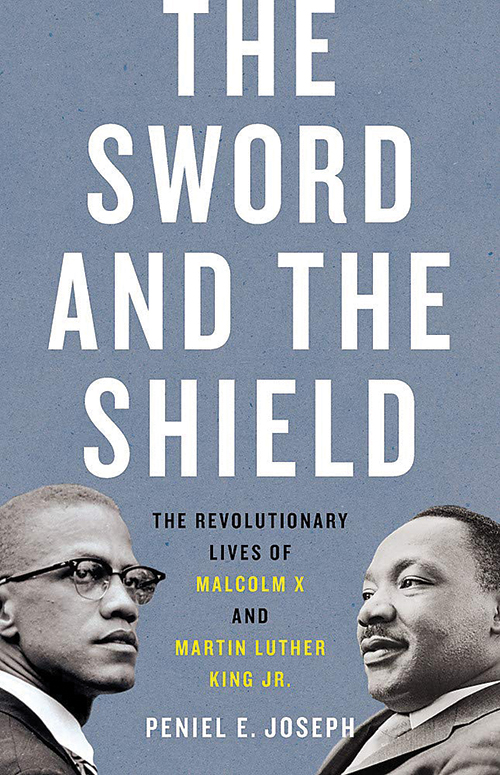

The Sword and the Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr.

Reviewed by J. E. McNeil

October 1, 2021

By Peniel E. Joseph. Basic Books, 2020. 384 pages. $30/hardcover; $18.99/paperback; $19.99/eBook.

Buy from QuakerBooks

Living through a historic era is no guarantee of understanding it. In 2000, when I first read Martin Luther King Jr.’s April 4, 1967 “Beyond Vietnam” speech given at Riverside Church in New York City, I saw a side of King I had never seen before: radical, antiwar, and anti-capitalism.

Peniel E. Joseph’s dual biography of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X throws light on the real men and their relationship, which shaped their legacies of continuing struggles after their martyrdom. The book opens at a critical point for the United States, the Civil Rights Movement, and for the lives of Martin and Malcolm. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was on the Senate floor, supported by Republicans and opposed by filibusters by Southern Democrats. Both Martin and Malcolm came to lobby for its passage. Martin was still on a crest from his “I Have a Dream” speech at the March on Washington the summer before and was afforded some insider privilege. Malcolm, recently having split from the Nation of Islam, which forbade political activities among its members, sought political leverage and stature as a leader of a large number of Blacks around the country and the world. Malcolm met Martin in the hall after Martin’s press conference—the only time they ever met.

The initial awkwardness of their meeting gave way to a rapport aided by a mutual understanding of black culture, their shared role as political leaders who doubled as preachers, and the rhythms of a common love for black humanity and yearning for black citizenship. Martin and Malcolm would never develop a personal friendship, but their political visions would grow closer together throughout their lives. . . . [T]heir relationship, even in that short meeting, defies the myths about their politics and activism.

The myth of Malcolm as the “evil twin” of Martin, the nonviolent advocate of racial equality with no economic component, endures. So does the myth of Malcolm as an “any means necessary” advocate for Black nationalism with no willingness to compromise.

Joseph tells their individual stories and their story together. They met by proxy over the years through Friend Bayard Rustin; Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) leader James Farmer; John Lewis, Julian Bond, and Stokely Carmichael of Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC); and others. Through these proxy debates and public pronouncements, “they were each building—both consciously and unconsciously—a public persona that served as a response to the other.” In the meanwhile, the predominately White press repeatedly ignored Martin’s more “radical pronouncements in [his] discussion . . . in favor of a more polished narrative of quietly determined moral leadership.” And they repeatedly framed Malcolm as only saying radical, militant things.

Showing a more complete story of each of these men, this account neither views Martin through rose-colored glasses nor Malcolm through a glass darkly. The homophobia of the Civil Rights Movements (since there was not just one movement) is touched on lightly in regards to Rustin. The sexism of both Martin and Malcolm is touched on in some depth, including Malcolm’s shifting attitude toward women in the last year of his life through his connections with SNCC. It’s a narrative of maneuvering, rivalry, and brotherhood, and a recasting of stories we think we know by heart. We are given peeks at the stories of Rustin, Ella Baker, Coretta Scott King, and others rising in prominence (or working behind the scenes) at the time. When King was in jail in 1964 in Selma, Malcolm came to speak.

Sitting on the dais next to Coretta, Malcom relayed a message that caught her off guard. “Mrs. King, . . . I want [Martin] to know that I didn’t come [to Selma] to make his job more difficult. I thought that if the white people understood what the alternative was that they would be willing to listen to Dr. King.”

There are minor factual lapses in the book—Fellowship of Reconciliation was founded in 1915 during World War One rather than World War Two. The Quaker faith of Bayard Rustin is ignored as it is in so many civil rights histories now that Rustin himself is no longer ignored for being gay. But these are small things. I would welcome future work from Joseph, exploring the stories of Rustin and Baker, other civil rights heroes who have been given little attention. With his generally accurate pen, Joseph could do some of the lesser-known figures justice, and readers real benefit.

Both leaders were assassinated, but the reaction was different. Though philosophically they had become very close—albeit approaching their positions from different directions—in death they were both simplified beyond recognition. The creation of the King holiday may have solidified Martin as a “founding father” and racial equality as a fundamental right, but Martin’s and Malcolm’s fight for economic justice was lost.

Martin and Malcolm “sought a moral and political reckoning with America’s long history of racial and economic injustice”—a reckoning that has yet to come. This book helps reframe the discussion and look toward the solution.

J. E. McNeil is a sixth-generation Southerner who grew up in Texas during the 1950s and ’60s. A particular point of pride for her is that in 1979 her late brother, Malcolm Bruce McNeil, helped draft the very first bill to make Juneteenth an official holiday while working for Al Edwards, the Texas State Representative from Houston.

Issue: October 2021

Quaker Book Reviews

==

MACOLM VS MARTIN

OCT 8, 2020

MACOLM VS MARTIN

OCT 8, 2020

Written by Jonathan Gordon

They didn’t hold high public office, they didn’t fight wars and they didn’t possess vast wealth and riches, and yet Dr Martin Luther King Jr and Malcolm X still managed to become two of the most iconic figures of the 20th century.

Rising to prominence at the height of the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s, each became equally revered and reviled by different parts of the United States. Both would ultimately come to be the de facto leader of their groups and each would meet an untimely and violent end at the hands of assailants whose identities and motives continue to be hotly debated.

In Dr King’s role as first president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and Malcolm X’s position as a minister and leading national spokesperson for the Nation of Islam (NOI), these two men often appeared to offer two conflicting arguments and approaches to the challenge of achieving racial justice and equality in America. What’s more, each existed in the public eye to a far greater and wider extent than any of their contemporaries fighting for African American rights and representation, and as a result each has developed their own legend. What we hope to do as we explore the lives of these two men is to find what linked them more than divided them and bring back some of the humanity of the men behind the myths. To that end we could think of no one better to guide us through this journey than the author of The Sword And The Shield: The Revolutionary Lives Of Malcolm X And Martin Luther King Jr, Dr Peniel E Joseph.

“The mythology around both men frames them as opposites,” he explains. “It frames Malcolm as Dr King’s evil twin. It frames Dr King as this saint who would just give everybody a hug if he was alive right now and that really takes away from understanding the depth and breadth of their political power, their political radicalism and their evolution over time.”

We’ll take a closer look at that evolution and convergence of ideas as we progress, but first it’s interesting to consider where each man came from and how that might have informed his world view. “Martin Luther King Jr is raised in an upper-middle class, elite household in Atlanta, Georgia,” Joseph tells us. “His father is a preacher, his mother is present in his life and it’s a very comfortable upbringing. Malcolm X is raised in Omaha and in Lansing, Michigan on farms, so he’s a country boy. His father is murdered by white supremacists when he’s six years old and his mother is put in a psychiatric facility, so he’s a foster child by the time he’s in elementary school. And then he becomes a hustler in Boston and Harlem as a teenager and he’s finally arrested for theft and spends seven years in prison. When Malcolm is in prison, Dr King is at Morehouse College, the most prestigious, historically black, all-men’s college that you could go to then or now. He goes and gets a theological degree at seminary school – Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania – and then gets a PhD at Boston University.”

“ THE MYTHOLOGY AROUND BOTH MEN FRAMES THEM AS OPPOSITES”

The strong religious upbringing of King clearly had a massive influence on his life, becoming a preacher himself as well as a political activist and integrating his faith deep into his speeches. Meanwhile, Malcolm’s tough upbringing and the tragedies he endured help to explain the righteous anger and pain he expressed as a minister for the NOI. However, Joseph does point out one curious similarity in their upbringing: “They’re both impacted by the movie Gone With The Wind. It premieres in Atlanta when Dr King is ten years old. Malcolm is 14 years old and sees that movie in Mason, Michigan, and talks about squirming in the movie theatre at all the racial stereotypes that the movie’s filled with. It’s filled with black women who are servants who are getting slapped in the face by white women who are masters, and it’s this sepia-toned, nostalgic vision of racial slavery. So that’s similar.”

It was during his time in prison for burglary that the then-Malcolm Little was introduced to Islam by some of his siblings and he joined the NOI. Its leader Elijah Muhammad took a personal interest in him, with letters being sent between them, before he was released in 1952. He abandoned his ‘slave name’ of Little and became Malcolm X, a minister in the NOI advocating for black separatism (which was the policy of the organisation), first in Chicago and later in Harlem, New York, which would become his base for years to come. The formative years of each man’s life are ultimately what frames them as polarised voices in a similar struggle.

“Malcolm X is really black America’s prosecuting attorney and he is going to be charging white America with a series of crimes against black humanity,” explains Joseph. “I argue in The Sword And The Shield that in a way his life’s work boils down to radical black dignity, and what he means by black dignity is really black people having the political self-determination to decide their own political futures and fates. They define racism and they define anti-racism and what social justice looks like for themselves. It’s connected to the United States, but globally it’s also connected to African decolonisation, African independence, Third World independence, Middle East politics, all of it.” Radical black dignity is also, importantly, about building up a black cultural identity that is independent of white America and building self-worth, which is a big part of where ideas like Black Power would later come from.

King naturally comes to things from a different direction. “Martin Luther King Jr is really the defence attorney,” says Joseph. “He defends black lives to white people and white lives to black people. He’s really advocating for radical black citizenship and his notion of citizenship is going to get more expansive over time; it’s going to be more than just voting rights and ending segregation. It’s going to become about ending poverty, food justice, health care, a living wage, universal basic income for everyone.” So radical black citizenship is about outward expression, about African Americans having an impact on the social systems that are in place, becoming engaged and demanding to be heard.

“True peace is not merely the absence of tension; it is the presence of justice”

17 September 1958

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere”

16 April 1963

“This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilising drug of gradualism”

16 April 1963

“True compassion is more than flinging a coin to a beggar. It comes to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring”

4 April 1967

“ THEIR DIFFERENCES REALLY BECOME DIFFERENCES OF TACTICS RATHER THAN GOALS ”

These two approaches, one that builds personal identity and another that looks to express that identity and have it recognised by a system that’s set up to ignore black voices, seem more complementary than adversarial when we look at them from a slight remove. “Their differences really become differences of tactics rather than goals,” says Joseph. “They’re both going to come to see that you need dignity and citizenship and those goals are going to converge over time, but it’s the tactics and how we get to those goals.”

Famously, though, they did not always see eye to eye. Malcolm X in particular took aim at King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference on multiple occasions (likely because he was a high-profile target and Malcolm was nothing if not media savvy). Malcolm regularly referred to King as an ‘Uncle Tom’, implying that his nonviolent strategy was either too accommodating to white America or even saying he was being subsidised by white America to keep African Americans defenceless. King for his part warned, “Fiery, demagogic oratory in the black ghettos, urging Negroes to arm themselves and prepare to engage in violence, as [Malcolm X] has done, can reap nothing but grief.”

And yet despite the animosity between the two men publicly, Malcolm X continually attempted to reach out to King over the years. He sent articles and NOI reading materials and invited him to speeches and meetings. On 31 July 1963, Malcolm X even publicly called for unity. “If capitalistic Kennedy and communistic Khrushchev can find something in common on which to form a United Front despite their tremendous ideological differences, it is a disgrace for Negro leaders not to be able to submerge our ‘minor’ differences in order to seek a common solution to a common problem posed by a Common Enemy,” he wrote, inviting Civil Rights leaders to join him in Harlem to speak at a rally. But they did not attend, perhaps because shortly after they would be attending the March on Washington and they were deep in planning. The slight was taken, though, with Malcolm dismissing the August 1963 event the ‘Farce on Washington’.

Despite the rhetoric, Joseph thinks Malcolm was still learning much from King’s activities. “Dr King is the person who helps mobilise Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963 and King is going to be facing German Shepherds and fire hoses and it’s going to be a big, global media spectacle,” he says. “King writes his famous Letter From Birmingham Jail during that period. Malcolm is in Washington DC for most of that spring as temporary head of Mosque No. 4 there and he’s really going to be influenced by King’s mobilisations – his ability to mobilise large numbers of people – even as he’s critical of King because of the nonviolence and the fact that so many kids and women are being brutalised.”

The really big shift in world view for Malcolm X comes the following year as he gradually breaks away from Elijah Muhammad (who was mired in allegations of extramarital affairs) and the NOI and seeks to define his own path forward. “By 1964 in ‘The Ballot Or The Bullet’ speech, you see Malcolm X talking about voting rights as part of black liberation and freedom. You see him in an interview with Robert Penn Warren saying that he and Dr King have the same goal, which is human dignity, but they have different ways of getting there,” explains Joseph.

“We are nonviolent with people who are nonviolent with us”

1963

“We didn’t land on Plymouth Rock, Plymouth Rock landed on us”

29 March 1964

“We can never get Civil Rights in America until our human rights are first restored”

25 August 1964

“You can’t separate peace from freedom because no one can be at peace unless he has his freedom”

4 April 1967

It’s around this time that Malcolm X left the United States for several months, travelling to Egypt, Lebanon, Liberia, Senegal, Nigeria, Ghana and Saudi Arabia, including taking his pilgrimage to Mecca where he received his new Islamic name, El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz. The trip made a big impression on him, and he spoke subsequently about how seeing Muslims of so many different ethnic and cultural backgrounds worshipping together opened his eyes to the real possibility of racial integration and peace.

“ KING BECOMES THIS VERY PROPHETIC, RADICAL FIGURE AFTER MALCOLM’S ASSASSINATION ”

All of this actually took place not long after the two men had met for what would be the first and only time. In the midst of the passing of the Civil Rights Act, as it was being filibustered on the Senate floor, Dr Martin Luther King Jr and Malcolm X crossed paths on Capitol Hill. “They both come and are talking to reporters and doing press conferences in support of the Civil Rights Act,” says Joseph. “They’re both coming there for the same reason. People are surprised that Malcolm is there and he’s watching the Senate and he’s doing his interviews and there’s a point where Malcolm is in the same room as Dr King and on the couch while Dr King is doing his press conference and they meet afterwards, exchanging pleasantries.” It was a moment captured by only a couple of photos, catching them mid-conversation with Malcolm recorded as saying, “I’m throwing myself into the heart of the Civil Rights struggle.”

Malcolm X continued to make overtures to King in the months that followed, offering him protection in St Augustine, Florida, that spring as protestors fought for desegregation of its beaches and playgrounds and later in Selma, Alabama, as King’s attention turned to voting rights where he felt he had a role to play. “I think Malcolm gave King more room to operate and I think Malcolm knew this,” says Joseph. “When he visits Selma shortly before his own death, he’s trying to visit Dr King in February of 1965 in Alabama but King is jailed and he gets to visit Coretta Scott King gives a speech and visits some of the student organisers. He tells Coretta Scott King that he’s only there to support her husband and he wants people to know that if her husband’s advocacy of voting rights is not accomplished that there are other alternative forces out there that are going to be led by him. So he definitely offers King more strategic leeway.”

Whether or not the two men could have ultimately found a way to coordinate their approaches in a less ad hoc fashion we will never know because on 21 February 1965, just days before the Selma to Montgomery marches were about to be attempted by King’s movement, Malcolm X was assassinated in New York. The exact details remain disputed, but we do know that he was about to speak at the Audubon Ballroom, where he was expected to announce plans for voter registration drives, denounce police brutality and call for the UN to speak up on human rights violations in America. As he began to speak a scuffle broke out, likely as a distraction, and a man approached the stage with a shotgun, shooting him. Two more men rushed the stage with pistols and shot him again as he lay on the floor. The impact of his death would be felt throughout the movement, and quite profoundly by King.

“One of the surprising things is that we don’t discuss the way in which the person who is most radicalised by Malcolm’s assassination is Martin Luther King Jr,” Joseph explains. “He breaks with Lyndon Johnson on 4 April 1967 with the Riverside Church speech in New York, where he says that the United States is the greatest purveyor of violence in the world. Malcolm had always talked about racial slavery and how racial slavery had shaped the present and King talks about that much more after 1965. He’s in Marks, Mississippi, helping to lead the Poor People’s Campaign and he’s in tears because there’s so much poverty there. He says that what the people in Marks, Mississippi, are experiencing is a crime and they’re going to go to Washington DC. Malcolm had always said that black poverty, racial segregation and violence were crimes, but Martin Luther King starts speaking in that language.”

As King turns his attention to economic inequality through the mid- to late-1960s, he digs deeper and deeper into the wider historic inequalities and injustices of America. “He becomes this very prophetic, radical figure after Malcolm’s assassination and he’s much more interested in race and blackness too,” says Joseph. “There’s a speech he makes in 1967 where he says they even tell you ‘A white lie is better than a black lie’. He gets into it in a granular way; and this is King, not Malcolm. It’s Dr King who says that the halls of the US Congress are ‘running wild with racism’. King is testifying before the Kerner Commission, the president’s riot commission, and talking about the depth and breadth of white racism. He speaks to the American Psychological Association in September 1967 and says that white people in the United States are producing chaos, blame black people for the chaos and say there would be peace if not for the chaos that they produce. He’s really much more candid and much more blunt, much more radical, much more revolutionary and there are no more meetings with the president of the United States.”

It is perhaps because they evolved and were willing to learn from one another that each has remained as relevant today as they were in the 1960s. “Even in this year of 2020 with George Floyd and Black Lives Matter and these global protest movements, the only way to understand these movements is to understand Malcolm and Martin who were talking about so much of these issues of police brutality and the criminal justice system, racial segregation and poverty and state-sanctioned violence,” says Joseph.

Which is why, adds Joseph, that getting beyond the mythology of these men is so important. “What did they actually do? What did they think? What were the networks that they connected with? Because both of them are in these really important networks with people like Bayard Rustin, who was the organiser of the March on Washington; James Baldwin; Ella Baker, who founded the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee; Fannie Lou Hamer, who Malcolm meets up with as a voting rights activist. They connect so many different networks. Globally too: Malcolm in Cairo with [Ghanaian president, Kwame] Nkrumah, Malcolm in Tanzania. Martin Luther King is a Nobel Peace Prize winner and spends a month in India. Both Malcolm and King know Nkrumah, Malcolm from Harlem and King in Ghana having met him in 1957. They’re extraordinary figures. Malcolm is the person who politicises Muhammad Ali. So they are these global revolutionary figures and they are subversive. They are trying to transform the status quo and unless we really watch that through line and follow them we can get stuck with them as these icons where we don’t understand they are both the sword and the shield.”

“ IT’S DR KING WHO SAYS THAT THE HALLS OF THE US CONGRESS ARE ‘RUNNING WILD WITH RACISM’ ”

At this point it seems clear that each man was somewhat more complex, multifaceted and evolving than the monolithic figures that are often depicted. The question that hangs around them, though, is could either of them have achieved as much as they did if the other hadn’t been there challenging them? “I think they both need each other,” concludes Joseph. “They both have misapprehensions about each other and they make mistakes about each other. King thinks Malcolm is this narrow, anti-white black nationalist. Malcolm thinks King is this bourgeois, reform-minded Uncle Tom when they start out. Neither of them are those things, so they both needed the other.”

What’s more, the contributions of each remain important to this day. “Dr King is this major global political mobiliser and the way in which he frames this idea of racial justice globally is very important, and the numbers he attracts are very important,” says Joseph. Meanwhile Malcolm has perhaps given us much of the vocabulary around racial justice even in the 21st century: “Malcolm is the first modern activist who is really saying black lives matter in a really deep and definitive way and becomes the avatar of the Black Power movement.” ■

Related Interests

Malcolm X

Martin Luther King Jr.

March On Washington For Jobs And Freedom

Public Sphere

FROM THIS ISSUE

No. 96

All About History

Related

They didn’t hold high public office, they didn’t fight wars and they didn’t possess vast wealth and riches, and yet Dr Martin Luther King Jr and Malcolm X still managed to become two of the most iconic figures of the 20th century.

Rising to prominence at the height of the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s, each became equally revered and reviled by different parts of the United States. Both would ultimately come to be the de facto leader of their groups and each would meet an untimely and violent end at the hands of assailants whose identities and motives continue to be hotly debated.

In Dr King’s role as first president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and Malcolm X’s position as a minister and leading national spokesperson for the Nation of Islam (NOI), these two men often appeared to offer two conflicting arguments and approaches to the challenge of achieving racial justice and equality in America. What’s more, each existed in the public eye to a far greater and wider extent than any of their contemporaries fighting for African American rights and representation, and as a result each has developed their own legend. What we hope to do as we explore the lives of these two men is to find what linked them more than divided them and bring back some of the humanity of the men behind the myths. To that end we could think of no one better to guide us through this journey than the author of The Sword And The Shield: The Revolutionary Lives Of Malcolm X And Martin Luther King Jr, Dr Peniel E Joseph.

“The mythology around both men frames them as opposites,” he explains. “It frames Malcolm as Dr King’s evil twin. It frames Dr King as this saint who would just give everybody a hug if he was alive right now and that really takes away from understanding the depth and breadth of their political power, their political radicalism and their evolution over time.”

We’ll take a closer look at that evolution and convergence of ideas as we progress, but first it’s interesting to consider where each man came from and how that might have informed his world view. “Martin Luther King Jr is raised in an upper-middle class, elite household in Atlanta, Georgia,” Joseph tells us. “His father is a preacher, his mother is present in his life and it’s a very comfortable upbringing. Malcolm X is raised in Omaha and in Lansing, Michigan on farms, so he’s a country boy. His father is murdered by white supremacists when he’s six years old and his mother is put in a psychiatric facility, so he’s a foster child by the time he’s in elementary school. And then he becomes a hustler in Boston and Harlem as a teenager and he’s finally arrested for theft and spends seven years in prison. When Malcolm is in prison, Dr King is at Morehouse College, the most prestigious, historically black, all-men’s college that you could go to then or now. He goes and gets a theological degree at seminary school – Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania – and then gets a PhD at Boston University.”

“ THE MYTHOLOGY AROUND BOTH MEN FRAMES THEM AS OPPOSITES”

The strong religious upbringing of King clearly had a massive influence on his life, becoming a preacher himself as well as a political activist and integrating his faith deep into his speeches. Meanwhile, Malcolm’s tough upbringing and the tragedies he endured help to explain the righteous anger and pain he expressed as a minister for the NOI. However, Joseph does point out one curious similarity in their upbringing: “They’re both impacted by the movie Gone With The Wind. It premieres in Atlanta when Dr King is ten years old. Malcolm is 14 years old and sees that movie in Mason, Michigan, and talks about squirming in the movie theatre at all the racial stereotypes that the movie’s filled with. It’s filled with black women who are servants who are getting slapped in the face by white women who are masters, and it’s this sepia-toned, nostalgic vision of racial slavery. So that’s similar.”

It was during his time in prison for burglary that the then-Malcolm Little was introduced to Islam by some of his siblings and he joined the NOI. Its leader Elijah Muhammad took a personal interest in him, with letters being sent between them, before he was released in 1952. He abandoned his ‘slave name’ of Little and became Malcolm X, a minister in the NOI advocating for black separatism (which was the policy of the organisation), first in Chicago and later in Harlem, New York, which would become his base for years to come. The formative years of each man’s life are ultimately what frames them as polarised voices in a similar struggle.

“Malcolm X is really black America’s prosecuting attorney and he is going to be charging white America with a series of crimes against black humanity,” explains Joseph. “I argue in The Sword And The Shield that in a way his life’s work boils down to radical black dignity, and what he means by black dignity is really black people having the political self-determination to decide their own political futures and fates. They define racism and they define anti-racism and what social justice looks like for themselves. It’s connected to the United States, but globally it’s also connected to African decolonisation, African independence, Third World independence, Middle East politics, all of it.” Radical black dignity is also, importantly, about building up a black cultural identity that is independent of white America and building self-worth, which is a big part of where ideas like Black Power would later come from.

King naturally comes to things from a different direction. “Martin Luther King Jr is really the defence attorney,” says Joseph. “He defends black lives to white people and white lives to black people. He’s really advocating for radical black citizenship and his notion of citizenship is going to get more expansive over time; it’s going to be more than just voting rights and ending segregation. It’s going to become about ending poverty, food justice, health care, a living wage, universal basic income for everyone.” So radical black citizenship is about outward expression, about African Americans having an impact on the social systems that are in place, becoming engaged and demanding to be heard.

“True peace is not merely the absence of tension; it is the presence of justice”

17 September 1958

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere”

16 April 1963

“This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilising drug of gradualism”

16 April 1963

“True compassion is more than flinging a coin to a beggar. It comes to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring”

4 April 1967

“ THEIR DIFFERENCES REALLY BECOME DIFFERENCES OF TACTICS RATHER THAN GOALS ”

These two approaches, one that builds personal identity and another that looks to express that identity and have it recognised by a system that’s set up to ignore black voices, seem more complementary than adversarial when we look at them from a slight remove. “Their differences really become differences of tactics rather than goals,” says Joseph. “They’re both going to come to see that you need dignity and citizenship and those goals are going to converge over time, but it’s the tactics and how we get to those goals.”

Famously, though, they did not always see eye to eye. Malcolm X in particular took aim at King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference on multiple occasions (likely because he was a high-profile target and Malcolm was nothing if not media savvy). Malcolm regularly referred to King as an ‘Uncle Tom’, implying that his nonviolent strategy was either too accommodating to white America or even saying he was being subsidised by white America to keep African Americans defenceless. King for his part warned, “Fiery, demagogic oratory in the black ghettos, urging Negroes to arm themselves and prepare to engage in violence, as [Malcolm X] has done, can reap nothing but grief.”

And yet despite the animosity between the two men publicly, Malcolm X continually attempted to reach out to King over the years. He sent articles and NOI reading materials and invited him to speeches and meetings. On 31 July 1963, Malcolm X even publicly called for unity. “If capitalistic Kennedy and communistic Khrushchev can find something in common on which to form a United Front despite their tremendous ideological differences, it is a disgrace for Negro leaders not to be able to submerge our ‘minor’ differences in order to seek a common solution to a common problem posed by a Common Enemy,” he wrote, inviting Civil Rights leaders to join him in Harlem to speak at a rally. But they did not attend, perhaps because shortly after they would be attending the March on Washington and they were deep in planning. The slight was taken, though, with Malcolm dismissing the August 1963 event the ‘Farce on Washington’.

Despite the rhetoric, Joseph thinks Malcolm was still learning much from King’s activities. “Dr King is the person who helps mobilise Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963 and King is going to be facing German Shepherds and fire hoses and it’s going to be a big, global media spectacle,” he says. “King writes his famous Letter From Birmingham Jail during that period. Malcolm is in Washington DC for most of that spring as temporary head of Mosque No. 4 there and he’s really going to be influenced by King’s mobilisations – his ability to mobilise large numbers of people – even as he’s critical of King because of the nonviolence and the fact that so many kids and women are being brutalised.”

The really big shift in world view for Malcolm X comes the following year as he gradually breaks away from Elijah Muhammad (who was mired in allegations of extramarital affairs) and the NOI and seeks to define his own path forward. “By 1964 in ‘The Ballot Or The Bullet’ speech, you see Malcolm X talking about voting rights as part of black liberation and freedom. You see him in an interview with Robert Penn Warren saying that he and Dr King have the same goal, which is human dignity, but they have different ways of getting there,” explains Joseph.

“We are nonviolent with people who are nonviolent with us”

1963

“We didn’t land on Plymouth Rock, Plymouth Rock landed on us”

29 March 1964

“We can never get Civil Rights in America until our human rights are first restored”

25 August 1964

“You can’t separate peace from freedom because no one can be at peace unless he has his freedom”

4 April 1967

It’s around this time that Malcolm X left the United States for several months, travelling to Egypt, Lebanon, Liberia, Senegal, Nigeria, Ghana and Saudi Arabia, including taking his pilgrimage to Mecca where he received his new Islamic name, El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz. The trip made a big impression on him, and he spoke subsequently about how seeing Muslims of so many different ethnic and cultural backgrounds worshipping together opened his eyes to the real possibility of racial integration and peace.

“ KING BECOMES THIS VERY PROPHETIC, RADICAL FIGURE AFTER MALCOLM’S ASSASSINATION ”

All of this actually took place not long after the two men had met for what would be the first and only time. In the midst of the passing of the Civil Rights Act, as it was being filibustered on the Senate floor, Dr Martin Luther King Jr and Malcolm X crossed paths on Capitol Hill. “They both come and are talking to reporters and doing press conferences in support of the Civil Rights Act,” says Joseph. “They’re both coming there for the same reason. People are surprised that Malcolm is there and he’s watching the Senate and he’s doing his interviews and there’s a point where Malcolm is in the same room as Dr King and on the couch while Dr King is doing his press conference and they meet afterwards, exchanging pleasantries.” It was a moment captured by only a couple of photos, catching them mid-conversation with Malcolm recorded as saying, “I’m throwing myself into the heart of the Civil Rights struggle.”

Malcolm X continued to make overtures to King in the months that followed, offering him protection in St Augustine, Florida, that spring as protestors fought for desegregation of its beaches and playgrounds and later in Selma, Alabama, as King’s attention turned to voting rights where he felt he had a role to play. “I think Malcolm gave King more room to operate and I think Malcolm knew this,” says Joseph. “When he visits Selma shortly before his own death, he’s trying to visit Dr King in February of 1965 in Alabama but King is jailed and he gets to visit Coretta Scott King gives a speech and visits some of the student organisers. He tells Coretta Scott King that he’s only there to support her husband and he wants people to know that if her husband’s advocacy of voting rights is not accomplished that there are other alternative forces out there that are going to be led by him. So he definitely offers King more strategic leeway.”

Whether or not the two men could have ultimately found a way to coordinate their approaches in a less ad hoc fashion we will never know because on 21 February 1965, just days before the Selma to Montgomery marches were about to be attempted by King’s movement, Malcolm X was assassinated in New York. The exact details remain disputed, but we do know that he was about to speak at the Audubon Ballroom, where he was expected to announce plans for voter registration drives, denounce police brutality and call for the UN to speak up on human rights violations in America. As he began to speak a scuffle broke out, likely as a distraction, and a man approached the stage with a shotgun, shooting him. Two more men rushed the stage with pistols and shot him again as he lay on the floor. The impact of his death would be felt throughout the movement, and quite profoundly by King.

“One of the surprising things is that we don’t discuss the way in which the person who is most radicalised by Malcolm’s assassination is Martin Luther King Jr,” Joseph explains. “He breaks with Lyndon Johnson on 4 April 1967 with the Riverside Church speech in New York, where he says that the United States is the greatest purveyor of violence in the world. Malcolm had always talked about racial slavery and how racial slavery had shaped the present and King talks about that much more after 1965. He’s in Marks, Mississippi, helping to lead the Poor People’s Campaign and he’s in tears because there’s so much poverty there. He says that what the people in Marks, Mississippi, are experiencing is a crime and they’re going to go to Washington DC. Malcolm had always said that black poverty, racial segregation and violence were crimes, but Martin Luther King starts speaking in that language.”

As King turns his attention to economic inequality through the mid- to late-1960s, he digs deeper and deeper into the wider historic inequalities and injustices of America. “He becomes this very prophetic, radical figure after Malcolm’s assassination and he’s much more interested in race and blackness too,” says Joseph. “There’s a speech he makes in 1967 where he says they even tell you ‘A white lie is better than a black lie’. He gets into it in a granular way; and this is King, not Malcolm. It’s Dr King who says that the halls of the US Congress are ‘running wild with racism’. King is testifying before the Kerner Commission, the president’s riot commission, and talking about the depth and breadth of white racism. He speaks to the American Psychological Association in September 1967 and says that white people in the United States are producing chaos, blame black people for the chaos and say there would be peace if not for the chaos that they produce. He’s really much more candid and much more blunt, much more radical, much more revolutionary and there are no more meetings with the president of the United States.”

It is perhaps because they evolved and were willing to learn from one another that each has remained as relevant today as they were in the 1960s. “Even in this year of 2020 with George Floyd and Black Lives Matter and these global protest movements, the only way to understand these movements is to understand Malcolm and Martin who were talking about so much of these issues of police brutality and the criminal justice system, racial segregation and poverty and state-sanctioned violence,” says Joseph.

Which is why, adds Joseph, that getting beyond the mythology of these men is so important. “What did they actually do? What did they think? What were the networks that they connected with? Because both of them are in these really important networks with people like Bayard Rustin, who was the organiser of the March on Washington; James Baldwin; Ella Baker, who founded the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee; Fannie Lou Hamer, who Malcolm meets up with as a voting rights activist. They connect so many different networks. Globally too: Malcolm in Cairo with [Ghanaian president, Kwame] Nkrumah, Malcolm in Tanzania. Martin Luther King is a Nobel Peace Prize winner and spends a month in India. Both Malcolm and King know Nkrumah, Malcolm from Harlem and King in Ghana having met him in 1957. They’re extraordinary figures. Malcolm is the person who politicises Muhammad Ali. So they are these global revolutionary figures and they are subversive. They are trying to transform the status quo and unless we really watch that through line and follow them we can get stuck with them as these icons where we don’t understand they are both the sword and the shield.”

“ IT’S DR KING WHO SAYS THAT THE HALLS OF THE US CONGRESS ARE ‘RUNNING WILD WITH RACISM’ ”

At this point it seems clear that each man was somewhat more complex, multifaceted and evolving than the monolithic figures that are often depicted. The question that hangs around them, though, is could either of them have achieved as much as they did if the other hadn’t been there challenging them? “I think they both need each other,” concludes Joseph. “They both have misapprehensions about each other and they make mistakes about each other. King thinks Malcolm is this narrow, anti-white black nationalist. Malcolm thinks King is this bourgeois, reform-minded Uncle Tom when they start out. Neither of them are those things, so they both needed the other.”

What’s more, the contributions of each remain important to this day. “Dr King is this major global political mobiliser and the way in which he frames this idea of racial justice globally is very important, and the numbers he attracts are very important,” says Joseph. Meanwhile Malcolm has perhaps given us much of the vocabulary around racial justice even in the 21st century: “Malcolm is the first modern activist who is really saying black lives matter in a really deep and definitive way and becomes the avatar of the Black Power movement.” ■

Related Interests

Malcolm X

Martin Luther King Jr.

March On Washington For Jobs And Freedom

Public Sphere

FROM THIS ISSUE

No. 96

All About History

Related