Myōe

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2015) |

Myōe 明恵 | |

|---|---|

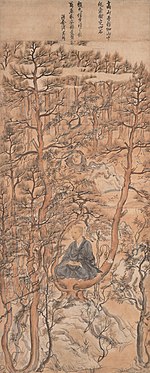

Myōe from woodblock print catalog Shūko Jusshu, mid- Eido Period | |

| Born | February 21, 1173 Yoshiwara village, Kii Province, Japan |

| Died | February 11, 1232 (aged 58) Kii Province, Japan |

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism in Japan |

|---|

|

Myōe (明恵) (February 21, 1173 – February 11, 1232) was a Japanese Buddhist monk active during the Kamakura period who also went by the name Kōben (Japanese: 高弁), and contemporary of Jōkei and Hōnen.

Biography[edit]

Myōe was born in what what is now the town of Aridagawa, Wakayama. His mother was the fourth daughter of Yuasa Muneshige, a local strongman who claimed descent from Taira Shigekuni, and from thence Emperor Takakura. His childhood name was Yakushi-maru. Orphaned at the age of nine, he was educated at Jingo-ji north of Kyoto by a disciple of Mongaku and was ordained as a priest in 1188 at Tōdai-ji. He was trained in both the Kegon and Kusha schools and trained in Shingon at Ninna-ji. He later also studied Zen Buddhism under Eisai, all by the age of 20. In medieval Japan, it was not uncommon for monks to be ordained in multiple sectarian lineages, and Myōe alternately signed his treatises and correspondence as a monk of various schools through much of his career.

However, at the age of 21, he refused a request participation in a national debate on the various schools of Buddhism, and at the age of 23 he broke off all ties with secular society and sought solitude in the mountains of Arida District in Kii Province, leaving behind a waka poem expressing his disgust for the politics of the various schools of Buddhism. Around this time, he cut off his right ear with a razor as a symbol of his rejection with society. At around the age of 26, he moved to Yamashiro Province, but after short time he returned to Kii Province where he spent the next eight years, living a nomadic existence. Myōe sought twice to go to India, in 1203 and 1205, to study what he considered true Buddhism amidst the perceived decline of the Dharma, but in both occasions, the kami of the Kasuga-taisha urged him to remain in Japan through oracle.

In 1206, he served as abbot of Kōzan-ji (高山寺), a temple of the Kegon school located near Kyoto,where he sought to unify the teachings of the various schools of Buddhism around the Avatamsaka Sutra. Myōe is perhaps most famous for his contributions to the practice and popularization of the Mantra of Light, a mantra associated with Shingon Buddhism but widely used in other Buddhist sects. Myōe is also well known for keeping a journal of his dreams for over 40 years which continues to be studied by Buddhists and Buddhist scholars, and for his efforts to revive monastic discipline along with Jōkei.

Myōe also strove to find ways to make the teachings of esoteric Buddhism more understandable to lay people; on the other hand, during his lifetime he was a scathing critic of his contemporary, Hōnen, and the new Pure Land Buddhist movement. As a response to the increasing popularity of the exclusive nembutsu practice, Myōe wrote two treatises, the Zaijarin (摧邪輪, "Tract for Destroying Heretical Views") and the follow-up Zaijarin Shōgonki (摧邪輪荘厳記, "Elaboration of the Zaijarin") that sought to refute Honen's teachings as laid out in the Senchakushū. Myōe agreed with Hōnen's criticism of the establishment, but felt that sole practice of the nembutsu was too restrictive and disregarded important Buddhist themes in Mahayana Buddhism such as the Bodhicitta and the concept of upāya. Nevertheless, Myōe also lamented the necessity of writing such treatises: "By nature I am pained by that which is harmful. I feel this way about writing the Zaijarin." (trans. Professor Mark Unno)[full citation needed]

In the later years of his life, Myōe wrote extensively on the meaning and application of the Mantra of Light. Myōe's interpretation of the Mantra of Light was somewhat unorthodox, in that he promoted the mantra as a means of being reborn in Sukhāvatī, the pure land of Amitābha, rather than a practice for attaining enlightenment in this life as taught by Kūkai and others. Myōe was a firm believer in the notion of Dharma Decline and sought to promote the Mantra of Light as a means of intercession.

Myōe was equally critical of the lax discipline and corruption of the Buddhist establishment, and removed himself from the capital of Kyoto as much as possible. At one point, to demonstrate his resolve to follow the Buddhist path, Myōe knelt before an image of the Buddha at Kōzan-ji, and cut off his own ear. Supposedly, the blood stain can still be seen at the temple to this day. Records for the time show that the daily regimen of practices for the monks at Kōzan-ji, during Myoe's administration, included zazen meditation, recitation of the sutras and the Mantra of Light. These same records show that even details such as cleaning the bathroom regularly were routinely enforced. A wooden tablet titled Arubekiyōwa (阿留辺畿夜宇和, "As Appropriate") still hangs in the northeast corner of the Sekisui'in Hall at Kōzan-ji detailing various regulations.

At the same time, Myōe was also pragmatic and often adopted practices from other Buddhist sects, notably Zen if it proved useful. Myōe firmly believed in the importance of upāya and sought to provide a diverse set of practices for both monastics and lay people. In addition, he developed new forms of mandalas that utilized only Japanese calligraphy and the Sanskrit Siddhaṃ script. Similar styles were utilized by Shinran and Nichiren. The particular style of mandala he devised, and the devotional rituals surrounding it, are recorded in his treatise, the Sanji Raishaku (Thrice-daily worship) written in 1215.[1]

In 1231, he was invited by the Yuasa clan to open the temple of Semui-ji in his hometown in Kii Province. The day following the ceremony, on January 19, 1232, he died at the age of 58.

Monastic Regulations promulgated by Myōe[edit]

In the wooden tablet at Kōzan-ji, Myōe listed the following regulations to all monks, divided into three sections:[note 1]

As Appropriate

- 06:00 - 08:00 PM, Liturgy: Yuishin kangyō shiki (唯心観行式, Manual on the Practice of Contemplating the Mind-Only)

- 08:00 - 10:00 PM, Practice once. Chant the Sambōrai (三宝礼, Revering the Three Treasures).

- 10:00 - 12:00 AM, Zazen (seated meditation). Count breaths.

- 12:00 - 06:00 AM, Rest for three [two-hour] periods.

- 06:00 - 08:00 AM, Walking meditation once. (Inclusion or exclusion should be appropriate to the occasion). Liturgy: Rishukyō raisan (理趣経礼賛, Ritual Repentance Based on the Sutra of the Ultimate Meaning of the Principle) and the like.

- 08:00 - 10:00 AM, Sambōrai. Chant scriptures for breakfast and intone the Kōmyō Shingon (Mantra of Light) forty-nine times.

- 10:00 - 12:00 PM, Zazen. Count breaths.

- 12:00 - 02:00 PM, Noon meal. Chant the Goji Shingon (五字真言, Mantra of the Five Syllables) five hundred times.

- 02:00 - 04:00 PM, Study or copy scriptures.

- 04:00 - 06:00 PM, Meet with the master (Myōe) and resolve essential matters.

Etiquette in the Temple Study Hall

- Do not leave rosaries or gloves on top of scriptures.

- Do not leave sōshi [bound] texts on top of round meditation cushions or on the half tatami-size cushions [placed under round cushions].

- During the summer, do not use day-old water for mixing ink.

- Do not place scriptures under the desk.

- Do not lick the tips of brushes.

- Do not reach for something by extending one's hand over scriptures.

- Do not enter [the hall] wearing just the white undergarment robes.

- Do not lie down

- Do not count [pages] by moistening one's fingers with saliva. Place an extra sheet of paper under each sheet of your sōshi texts.

Etiquette in the Buddha-Altar Hall

- Keep the clothes for wiping the altar separate from that for wiping the Buddha[-statue].

- During the summer (from the first day of the fourth month to the last day of the seventh month), obtain fresh water [from the well] morning and evening for water offerings.

- Keep the water offerings and incense burners for buddhas and bodhisattvas separate from those for patriarchs.*

- When you are seated on the half-size cushions, do not bow with your chin up.

- Do not place nose tissues and the like under the half-tatami size cushions.

- Do not let your sleeves touch the offering-water bucket.

- Do not put the [altar] rings on the wooden floor; they should be placed high.

- Place a straw mat at your usual seat.

- The regular sutra for recitation is one fascicle of the Avatamsaka Sutra (or half a fascicle). The three sutras should be read alternately every day.

- When traveling, you should read them after returning.

- The Gyōganbon ("Chapter on Practice and Vow"), Yuigyōkyō ("Sutra of the Buddha's Last Teachings"), and Rokkankyō ("Sutra in Six Fascicles") should all be read alternately one fascicle a day.

— The Kegon School Shamon Kōben [Myoe]

Myōe Kishū Cenotaphs[edit]

The Myōe Kishū Cenotaphs (明恵紀州遺跡率都婆, Myōe Kishū iseki sotsu tōba) is a collective designation for a group of memorial stones erected by Myōe's disciple Kikai shortly after Myōe's death. A total of seven cenotaphs were constructed, one at the place of his birth, and the other six at locations in Kii Province where he had trained. Originally made of stone, they were replaced by sandstone in 1345. Each is made of sandstone, from 1.5 to 1.7 meters high, with a capstone. [2] Four are located in the town of Aridagawa, two in the town of Yuasa and one in the city of Arida. Six of the seven were designated a National Historic Site in 1931.[3] The original of the seventh centotaph (located in Aridagawa) was lost and replaced in 1802, and was excluded from the designation.

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Reprinted with permission from Professor Mark Unno from the book Shingon Refractions: Myōe and the Mantra of Light

References[edit]

- ^ Gohonzon Shu: Dr. Jacquie Stone on the Object of Worship Archived April 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Isomura, Yukio; Sakai, Hideya (2012). (国指定史跡事典) National Historic Site Encyclopedia. 学生社. ISBN 4311750404.(in Japanese)

- ^ "明恵紀州遺跡率都婆" [Myōe kishū iseki-ritsu-to baba] (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

Further reading[edit]

- Abe, Ryūichi (2002). Mantra, Hinin, and the Feminine: On the Salvational Strategies of Myōe and Eizon, Cahiers d'Extrême-Asie, Vol. 13, 101 - 125

- Buswell, Robert E., Lopez, Donald S. Jr. (2014). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, Princeton University Press, p. 558

- Girard, Frédéric (1990). Un moine de la secte Kegon à Kamakura (1185-1333), Myôe (1173-1232) et le Journal de ses rêves, Paris: Ecole française d'Extrême-Orient. ISBN 285539760X

- Kawai, Hayao; Unno, Mark (1992). The Buddhist priest Myōe: a life of dreams. Venice, CA: Lapis. ISBN 0932499627

- Frédéric Girard, La doctrine du germe de la foi selon l’Ornementation fleurie, de Myōe (1173-1232). Un Fides quaerens intellectum dans le Japon du xiiie siècle, Paris, Collège de France, Institut des hautes études japonaises, collection Bibliothèque de l’Institut des hautes études japonaises, 2014, 137 p.

- Morell, Robert E. (1982). Kamakura Accounts of Myōe Shonin as Popular Religious Hero, Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 9 (2-3), 171-191

- Mross, Michaela (2016). Myōe's Nehan kōshiki: An Annotated Translation, Japanese Journal of Religious Studies Volume 43 (1), Online supplement 2, 1–20

- Tanabe, George (1992). Myoe the Dreamkeeper: Fantasy and Knowledge in Early Kamakura Buddhism. Harvard University Asia Center. ISBN 9780674597006

- Unno, Mark (2004). Shingon Refractions: Myōe and the Mantra of Light. Somerville MA, USA: Wisdom Publications, ISBN 0-86171-390-7

메이에

| 메이에 | |

|---|---|

| 승안 3년 1월 8일 - 관희 4년 1월 19일 ( 음력 ) ( 1173년 2월 21일 - 1232년 2월 11일 < 율리우스력 >) | |

메이에 상인(『집고 십종』) | |

| 유명 | 약사 원 |

| 호 | 메이에보(방호) |

| 諱 | 성밸브→고밸브 |

| 존칭 | 메이에 상인, 栂尾上人 |

| 직물 | 기이쿠니 아리타군 이시가키 쇼요 시 하라 무라 |

| 몰지 | 다카야마 절 |

| 종지 | 화엄종 |

| 사원 | 다카야마 절 |

| 스승 | 상각 |

| 제자 | 희해 |

| 저작 | 『매달린 고리』 등 다수 |

| 묘 | 다카야마 데라 선당원 |

메이에 (마에에)는, 가마쿠라 시대 전기의 화엄종 의 스님 . 법설은 고변 (こ弁). 메이에 상인·토리오(토가노) 상인이라고도 불린다. 아버지는 평중국 . 어머니는 유아사 무네시게 의 네 여자. 현재의 와카야마현 아리타가와마치 출신. 화엄종 중흥의 조 라고 불린다 [주석 1] .

평생 [ 편집 ]

승안 3년( 1173년 ) 1월 8일, 다카쿠라 상황 의 무자소에 묻은 히라 시게 나라 와 기이국의 유력자였던 유아사무 네 네 소녀 로서 기이쿠니 아리타군 이시가키쇼 요시하라무라(현: 와카야마현 아리타가와초 환희사 나카고시 ) 에서 태어났다. 유명 은 야쿠시마루 .

치승 4년( 1180년 ), 9세(수년.이하 같다)로 하여 부모를 잃고, 다음해, 가오슝산 신호사 에 문각 의 제자로 삼촌의 상각 에 사사(후, 문각에도 사사), 화엄 5교장 · 야사 논 을 읽었다 [1] . 문치 4년( 1188년 )에 출가 , 도다이지 에서 구족계 를 받았다. 법설은 성변 (나중에 고변 으로 개명). 니와 지 에서 진언 밀교 를 실존 이나 흥연 하게, 도다이지의 존승원에서 화엄종 · 구사무네 의 교학을 경아나 성사 에 , 오 흐를 존인 으로 , 선 을에이사이 에 배우고 미래를 촉망받았다 [1] [2] . 20세 전후의 메이에는 입문서의 종류를 많이 필사하고 있다 [3] .

그러나 21세 때 국가적 법회 에의 참가 요청 [주석 2] 을 거부하고 23세에 속연을 끊어 기이국 아리 타군 백조로 편세하고, 이후 약 3년에 걸쳐 시라카미산에서 수행 을 비난했다 [4] . 이 편세했을 때에 읊은 와카가 「야마데라는 법사 쿵쿵해서 헛소리가 들리지 않고 심청 쿠바쿠소후쿠(변소의 일)에도」이다. 이 무렵 인간을 그만두고 조금이라도 여래의 흔적을 밟고 싶어 오른쪽 귀의 외이를 면도로 스스로 잘라냈다. 26세 무렵, 가오슝산의 문각의 권유로 야마시로 쿠니 토리오 (토가노오)에 살고, 화엄의 교학을 강구한 적도 있었다 [주석 3] 가, 그 해의 가을, 10여명의 제자 함께 다시 흰색 위로 옮겼다 [2] [3] . 그 후, 약 8년간은 히타치 등 기이국내를 전전하면서 주로 기이에 체재하여 수행과 학문의 생활을 보냈다 [3] . 그동안, 원구 원년( 1205년 ), 석가 에 대한 사모의 마음이 깊은 명혜는 『대당천축리정기』(다이토우텐지쿠리테이키)를 만들고, 천축 ( 인도 )에 건너 불상을 순례 하자 라고 기획했지만, 카스 가 묘진신탁 때문에 이를 포기했다. 명혜는 또 이에 앞서 건인 2년(1202년)에도 인도로 건너려고 했지만, 이때는 병 때문에 단념하고 있다 [2] [3] [5] .

遁世僧가 된 메이에는, 겐나이 원년( 1206년 ), 후 토리바 상황에서栂尾의 땅을 하사되어 다카야마 절을 개산하고, 화엄 교학의 연구 등의 학문이나 좌선 수행 등의 관행에 , 계율 을 중시하고 현밀 제종의 부흥에 노력했다 [5] . 명혜는 화엄의 가르침과 밀교와의 통일·융합을 도모하고, 이 가르침은 이후 화엄밀교라고 불렸다 [3] . 다카야마데라 절은 ' 화엄경 '의 '일출에서 먼저 고산을 비추는'이라는 구에 의했다고 한다 . 이 땅에는 정관 년( 859년 -877 년 )부터 「도가오(토가오)사」라고 하는 고사가 있었지만 세월을 거쳐 현저하게 황폐하고 있어, 메이에이는 이것에 개수를 더해 도장으로 한 [주석 4] .

메이에는 법상종 의 정경 이나 삼론종 의 명편이 되는 초인적인 학승이라고도 평가된다 [5] 가, 학문으로서의 교설 이해보다 실제의 수행을 중시하고, 힘들게 계율을 지켜 몸 를 갖게 하는 것은 매우 근엄했다 [3] . 상각으로부터는 전법 관정 을 받고 있어 학문 연구와 실천 수행의 통일을 도모했다 [2] . 그 인품은, 무욕무나로 해 청렴, 게다가 세속권력·권세를 두려워하는 곳이 어쩔 수 없었다. 그가 세운 화엄밀교는, 만년에 이르기까지 속인이 이해하기 쉽도록 여러가지로 고안된 것이었다 [3] . 예를 들면, 재가 의 사람들에 대해서는 3시 3호 예의 행 의에 의해, 「관무량 수경」에 설하는 고급 상생에 의해서 극락 왕생할 수 있다고 하고, 「난무 3호 후생 태어나게 급에」혹은 「난무 3보 보제심, 현 당 2세소원원만」등의 말을 주창하는 것을 강조하는 등 [ 6 ] [ 7 ]의 제창을 배우고, 그것에 의해 종래의 학문 중심의 불교로부터의 탈피를 도모하려고 하는 일면도 있었다 [8] . 덧붙여 마츠오 고지 는, 메이에를 조사 로 하는 교단을 「신의화엄교단」이라고 부르고 있다 [4] .

건력 2년( 1212년 ), 법연 비판의 책 ' 고사륜 '을 저술하고 있으며, 이듬해에는 '고사륜장엄기'를 저술하고 그것을 보충하고 있다. 승구 3년( 1221년 )의 승구의 난 에서는 후도바가미 황방의 패병을 덮고 있다 [2] . 정응 2년( 1223년 ) 7월 , 메이에의 교단에 의해 야마시로 쿠니 젠묘지의 낙경 공양이 행해졌지만, 이 절은, 나카미몬 종행 의 후처가 승구의 난의 수모자의 혼자로서 가마쿠라 에의 호송중에 참살된 남편의 보제를 불러 내기 위해서 지어진 아마 데라 이자, 본존 은 다카야마데라에 안치되어 있던 석가 여래상이 천천한 것이었다 [9] .

명혜는 부처의 설 계율을 중시하는 것이야말로 그 정신을 받아들이는 것이라고 주장하고, 평생에 걸쳐 계율의 호지와 보급을 몸으로 실천했다 [10] . 마치다 무네봉은 “ 히오카 라는 말에는 인도 불교 이래의 계율을 지키는 사람이라는 엄숙한 의미가 포함되어 있지만, 그 자격을 채우는 것은 어쩌면 긴 일본 불교사 속에서 명혜 정도일지도 모른다. "라고 말한다 [11] . 또한 당시 확산되고 있던 정토제종의 진출을 저지하기 위해 고민하고 있어, 현밀제종 특히 밀교 속에서 있어야 할 신앙을 잡아, 그 보급과 선교에 노력했다 [1] .

만년은 강의, 설계, 좌선 수행에 노력해 광명진언 의 보급에도 노력했다. 관희 3년( 1231년 )에는 고지인 기슈 시무반사 의 개기로 유아사씨 에게 초대되었다. 다음 관희 4년( 1232년 ) 1월 19일, 미륵 의 보호를 주창하면서 천화했다 [2] . 향년 60(만 58세몰).

인물 [ 편집 ]

메이에는 와카 에도 길고 있어 집집 『메이에 상인 와카집』이 있다. 다음 단가 가 알려져 있다.

무라사키의 구름을 향해 노조미 야드 바람에 매달린 등나무

아카 아카 아 아 아 아 아 아 아 아 아 아 아 아 아 아 아야

꿈의 세상에서 우울해지면 어떠세요

또한 에사이 청래의 차 의 씨앗 을 栂尾에 뿌려 차의 보급의 계기를 이룬 것은 유명하다 [2] [주석 5] .

승구의 난으로 패병을 걸린 것을 기연으로 가마쿠라 쪽 총사령관으로 입경한 롯바라 탐제 초대장관(나중의 가마쿠라 막부 제3대 집권 ) 호조 태시 와의 친교가 시작되었다. 야마모토 칠평 에 의하면, 타이시는 메이에의 학덕을 깊이 존경하고, 메이에는 타이시의 정치사상, 특히 어성패 식목 의 제정의 기초가 되는 「도리」의 사상형세에 큰 영향을 주고 있다 [12] . 그 학덕은 고도바 상황·호조 태시 뿐만 아니라, 공가 에서는 쿠조 겐지 , 쿠조 도가 , 니시조지 공경 , 무가 에서는 아다치 경성 , 부인에서는 히라토쿠코 ( 건례문원 ) 등 많은 사람들로부터의 존경을 모았다 1] [5] .

메이에의 비인 구제 신화 [ 편집 ]

메이에의 죽음 후, 제자의 키미는 「타카야마데라 메이에 상인 행장」을 썼지만, 그 중에 석존이 중생 구제를 위해서는, 미즈로부터의 신명을 고민하지 않았다고 들은 메이에가, 16세 로 등단 수계해 얼마 지나지 않았을 무렵, 기이의 후지시로 왕자 [주석 6] 의 한센병 환자를 돕기 위해 자기의 육신을 주는 각오였다는 일절이 있다 [13] . 이것은 일종의 비인 구제 신화라고 한다 [13] .

메이에의 저작 [ 편집 ]

주요 저서에는, 정토종 을 펼친 법연의 「선택 본원념 불집」(선택집)을 읽고 이것을 비판한 상술한 「갈매기 고리 」(자이자린 , 바르게는 「동일향 전수종 선택 집중 악사륜 ') 전 3권, '동장엄기' 1권이 있다.

『화엄경』에서 고창되는 보리심 을 중시한 메이에이는 『쿠사키 링』・『동장엄기』에서 칭명념불 이야말로 정토왕생의 정업이며, 오로지 염불 을 주창함으로써 구원받는다고 한다 법연의 교설( 전수념불 )에 대해 그 저작에는 대승불교 에 있어서의 발보제심 ( 깨달음 을 얻고 싶은 마음)이 부족하다고 격렬하게 이를 비난하고 있다.

40년에 걸친 관행에서의 몽상을 기록한 『꿈기』 외, 저작은 70여권에 그리고 『유심 관행식』 『삼시 삼보 예석』 『화엄 불광 삼매 관비 보장』 화엄유심의」 「4자 강식」 「입해탈문의」 「화엄신종의」 「광명진언구의석」 등이 있다 [1] [2] . 메이에의 저작을 수재한 간본에는 다음이 있다.

- 『메이에 상인집』쿠보타 아츠시 , 야마구치 아키호역주, 이와나미 문고 , 초판 1981년, 개판 2009년/와이드판 1994년.

- 『메이에 상인 전기』히라이즈미 가역 주 , 코단샤 학술 문고 , 초판 1980년

- 『일본 사상대계 15 가마쿠라 구 불교』(이와나미 서점, 초판 1971년, 신장판 1995년)에, 타나카 쿠오 교주 「쿠시사와 권상」과 「각선망기」(제자장원의 필기에 의한 것)

- 『일본 고전 문학대계 83 假名法語集』(이와나미 서점, 초판 1964년)에, 미야자카 아츠카츠 교주「토리오 아키에 상인 유훈」

- 『대승불전 중국・일본편 제20권 에이니시 아키에』( 중앙공론사 , 1988년)에 다카하시 히데에이 (현대어 번역) 주해 「각폐망기」와 「광명진언 토사 권신기」

- 『일본의 명저 5 법연 메이에』(중앙공론사, 초판 1971년, 신판・중공 벅스, 1983년)에, 사토 나루스케 (현대 어역) 주해로 「갈매기 고리」와 「상인 유훈」

- 『메이에 상인가 집화 가문학대계 60』 히라노 다에 주해( 쿠보타 준 감수, 메이지 서원 , 2013년). ISBN 4757601484 .

메이에에 관한 평전, 수필, 작품 연구 등 [ 편집 ]

- 다나카 쿠오 『메이에』요시카와 히로후미칸 < 인물총서 >, 신장판 1988년. ISBN 4642051260

- 오쿠다 이사오『메이에 편력과 꿈』도쿄 대학 출판회 , 1994년 11월. ISBN 4130230247

- 『메이에 상인 꿈기역주』오쿠다 이사오, 히라노 다에, 마에카와 켄이치편, 공부 출판 , 2015년 2월. ISBN 4585210245 .

- 기노 카즈요시「메이에 상인 조용하고 투명한 삶의 방식」PHP 연구소 , 1996년 10월. ISBN 4569552951 .

- 『다카야마 절의 미술 메이에 상인과 조수 희화 연고의 절』 다카야마 절 감수, 츠치야 타카히로편, 요시카와 히로후미칸 , 2020년. ISBN 4642083839

- 다음은 문학 작품

- 시라스 마사코「메이에 상인」코단샤 문예 문고 , 1992년 3월. ISBN 4061961667 / 신 시오샤(아사조판 ), 1999년 11월

- 가와이 하야오『메이에 꿈을 사는』 교토 마츠카시와사, 1987년 4월(법장관 판매). 코단샤 <고단샤α문고>, 1995년 10월. ISBN 4062561182

- 미츠오카 아키라「사랑 메이에」분예 춘추 , 2005년 8월. ISBN 4163673709

- 사이토 유키코 「키요타키가와 메이에・자이의 생애」호조칸 , 2006년

- 이소베 타카시 「화엄종 사문 명혜 의 평생」대학교육 출판, 2006년

- 테라린 아키라 「소설 메이에」 대법 윤각 , 2006년

- 우에다 342『이 세상생 니시유키・료칸・메이에・미치모토』신 시오샤 1984년, 신시오 문고 , 1996년. 요미우리 문학상 수상

- 미즈키 시게루「신비가 열전 게이노 1」카도카와 서점 , 나중에 「미즈키 시게루 만화 대전집」 코단샤. 만화

- 타카세 센도「메이에 호리오 다카야마지 비화」현 서방 (상·하), 2018년. ISBN 978-4863291782 .

각주 [ 편집 ]

주석 [ 편집 ]

- ^ 화엄종은, 화엄경에 근거하는 남도 롯종의 일학파. 나라 시대 에 융성했지만 헤이안 시대 에는 있으면 세력을 잃고, 천력 원년( 947년 )에 광지 가 화엄 전수도장으로서 도다이지 존승원을 설립해 약간 쇠세를 되찾았지만, 그 이후, 다시 부진에 빠졌다. 후지타 (1966) p.178

- ↑ 이것을 「공청」이라고 부른다. 마츠오 (1995) p.37 .

- ^ 이 때, 메이에는 문각보다, 본존으로서 운경작의 석가여래상을 주는 것으로 알려져 있다. 후지타 (1966) p.178

- ^ 승구 원년(1219년)에는 김당 이 완성되어 쾌경작의 석가여래상이 안치되어 가록 원년( 1225년 )에는 진수당, 가록 3년( 1227년 )에는 삼중 탑 등도 건립되어 명혜재세중, 다이몬과 아미타도도 만들어졌다. 후지타 (1966) p.178

- ^ 이것에 의해, 호리오는 나중에 차의 산지가 되고 있다.

- ↑ 현대의 후지시라 신사 . 99 왕자 중 하나. 왕자란 참배 도상에서 의례 를 하는 장소를 말한다.

찾아보기 [ 편집 ]

- ↑ a b c d e 케이실 (1979) pp.120-121

- ↑ a b c d e f g h 납부 (2004)

- ↑ a b c d e f g h 후지타 (1966) p.178

- ↑ a b 마츠오 (1995) p.37

- ↑ a b c d 큰 모퉁이 (1989) p.209

- ↑ 『삼시삼호예석』 - 일본대장경. 제42권 종전부 화엄종장 소

- ^ 묘법 만다라의 형상의 기원을 둘러싸고 2

- ↑ 이에나가(1982) pp.128-129

- ↑ 마츠오(1995) pp.136-137

- ↑ 아미노 (1997) p.139

- ↑ 마치다(1998)

- ↑ 야마모토 (1982)

- ↑ a b 마츠오 (1995) p.102

참고 문헌 [ 편집 ]

- 후지타 케이세 「메이에 상인 수상 좌선승상」 「일본 문화사 3 가마쿠라 시대」쓰쿠마 서방 , 1966년 1월.

- 케이무로 포스나이 저 「메이에」, 일본 역사대사전 편집위원회 편 「일본역사대사전 9 미와」카와데서방신사 , 1979년 11월.

- 야마모토 칠평『일본적 혁명의 철학―일본인을 움직이는 원리』PHP 연구소 , 1982년 1월. ISBN 4569209130 .

- 이에나가 사부로 “일본 문화사(제2판)” 이와나미 서점 < 이와나미 신서 >, 1982년 3월. ISBN 4-00-420187-X .

- 오스미 카즈오 저 「난토 키타미네-구 불교의 자기 변혁」, 노가미 히로 편 「아사히 백과 일본의 역사 4중세Ⅰ」아사히 신문사 , 1989년 4월. ISBN 4-02-380007-4 .

- 마츠오 고지 “가마쿠라 신불교의 탄생” 코단샤〈고단샤 현대 신서〉, 1995년 10월. ISBN 4-06-149273-X .

- 아미노 요시히코『일본 사회의 역사(중)』 이와나미 서점 <이와나미 신서>, 1997년 7월. ISBN 4-00-430501-2 .

- 마치다 소나무『법연 대명혜 가마쿠라 불교의 종교 대립』코단샤〈고단샤 선서 메치에〉, 1998년 10월. ISBN 4062581418 .

- 納冨常天著「明恵」、小学館編『日本大百科全書』小学館〈슈퍼 니포니카 Professional Win판〉、2004년 2월. ISBN 4099067459 .

관련 항목 [ 편집 ]

明恵

| 明恵 | |

|---|---|

| 承安3年1月8日 - 寛喜4年1月19日(旧暦) (1173年2月21日 - 1232年2月11日〈ユリウス暦〉) | |

明恵上人(『集古十種』) | |

| 幼名 | 薬師丸 |

| 号 | 明恵房(房号) |

| 諱 | 成弁→高弁 |

| 尊称 | 明恵上人、栂尾上人 |

| 生地 | 紀伊国有田郡石垣庄吉原村 (現:和歌山県有田川町歓喜寺中越) |

| 没地 | 高山寺 |

| 宗旨 | 華厳宗 |

| 寺院 | 高山寺 |

| 師 | 上覚 |

| 弟子 | 喜海 |

| 著作 | 『摧邪輪』他多数 |

| 廟 | 高山寺禅堂院 |

明恵(みょうえ)は、鎌倉時代前期の華厳宗の僧。法諱は高弁(こうべん)。明恵上人・栂尾(とがのお)上人とも呼ばれる。父は平重国。母は湯浅宗重の四女。現在の和歌山県有田川町出身。華厳宗中興の祖と称される[注釈 1]。

生涯[編集]

承安3年(1173年)1月8日、高倉上皇の武者所に伺候した平重国と紀伊国の有力者であった湯浅宗重四女の子として紀伊国有田郡石垣庄吉原村(現:和歌山県有田川町歓喜寺中越)で生まれた。幼名は薬師丸。

治承4年(1180年)、9歳(数え年。以下同様)にして両親を失い、翌年、高雄山神護寺に文覚の弟子で叔父の上覚に師事(のち、文覚にも師事)、華厳五教章・倶舎頌を読んだ[1]。文治4年(1188年)に出家、東大寺で具足戒を受けた。法諱は成弁(のちに高弁に改名)。仁和寺で真言密教を実尊や興然に、東大寺の尊勝院で華厳宗・倶舎宗の教学を景雅や聖詮に、悉曇を尊印に、禅を栄西に学び、将来を嘱望された[1][2]。20歳前後の明恵は入門書の類を数多く筆写している[3]。

しかし、21歳のときに国家的法会への参加要請[注釈 2]を拒み、23歳で俗縁を絶って紀伊国有田郡白上に遁世し、こののち約3年にわたって白上山で修行をかさねた[4]。この遁世した時に詠んだ和歌が「山寺は法師くさくてゐたからず心清くばくそふく(便所のこと)にても」である。この頃、人間を辞して少しでも如来の跡を踏まんと思い、右耳の外耳を剃刀で自ら切り落とした。26歳のころ、高雄山の文覚の勧めで山城国栂尾(とがのお)に住み、華厳の教学を講じたこともあった[注釈 3]が、その年の秋、10余名の弟子とともにふたたび白上に移った[2][3]。こののち、約8年間は筏立など紀伊国内を転々としながら主に紀伊に滞在して修行と学問の生活を送った[3]。その間、元久元年(1205年)、釈迦への思慕の念が深い明恵は『大唐天竺里程記』(だいとうてんじくりていき)をつくり、天竺(インド)へ渡って仏跡を巡礼しようと企画したが、春日明神の神託のため、これを断念した。明恵はまた、これに先だつ建仁2年(1202年)にもインドに渡ろうとしたが、このときは病気のため断念している[2][3][5]。

遁世僧となった明恵は、建永元年(1206年)、後鳥羽上皇から栂尾の地を下賜されて高山寺を開山し、華厳教学の研究などの学問や坐禅修行などの観行にはげみ、戒律を重んじて顕密諸宗の復興に尽力した[5]。明恵は華厳の教えと密教との統一・融合をはかり、この教えはのちに華厳密教と称された[3]。高山寺の寺号は、『華厳経』の「日出でて先ず高山を照らす」という句によったといわれている[3]。この地には貞観年間(859年-877年)より「度賀尾(とがお)寺」という古寺があったものの年月を経て著しく荒廃しており、明恵はこれに改修を加えて道場とした[注釈 4]。

明恵は、法相宗の貞慶や三論宗の明遍とならぶ超人的な学僧とも評される[5]が、学問としての教説理解よりも実際の修行を重視し、きびしく戒律を護って身を持することきわめて謹厳であった[3]。上覚からは伝法灌頂を受けており、学問研究と実践修行の統一を図った[2]。その人柄は、無欲無私にして清廉、なおかつ世俗権力・権勢を怖れるところがいささかもなかった。かれの打ち立てた華厳密教は、晩年にいたるまで俗人が理解しやすいようさまざまに工夫されたものであった[3]。たとえば、在家の人びとに対しては三時三宝礼の行儀により、『観無量寿経』に説く上品上生によって極楽往生できるとし、「南無三宝後生たすけさせ給へ」あるいは「南無三宝菩提心、現当二世所願円満」等の言葉を唱えることを強調するなど[6][7]、後述するように、表面的には専修念仏をきびしく非難しながらも浄土門諸宗の説く易行の提唱を学びとり、それによって従来の学問中心の仏教からの脱皮をはかろうとする一面もあった[8]。なお、松尾剛次は、明恵を祖師とする教団を「新義華厳教団」と呼んでいる[4]。

建暦2年(1212年)、法然批判の書『摧邪輪』を著しており、翌年には『摧邪輪荘厳記』を著してそれを補足している。承久3年(1221年)の承久の乱では後鳥羽上皇方の敗兵をかくまっている[2]。貞応2年(1223年)7月、明恵の教団によって山城国善妙寺の落慶供養がおこなわれたが、この寺は、中御門宗行の後妻が承久の乱の首謀者のひとりとして鎌倉への護送中に斬殺された夫の菩提を弔うために建てた尼寺であり、本尊は高山寺に安置されていた釈迦如来像が遷されたものであった[9]。

明恵は、仏陀の説いた戒律を重んじることこそ、その精神を受けつぐものであると主張し、生涯にわたり戒律の護持と普及を身をもって実践した[10]。町田宗鳳は「比丘という言葉には、インド仏教以来の戒律を守る人という厳粛な意味が含まれているが、その資格を満たすのは、ひょっとしたら長い日本仏教史の中で、明恵ぐらいかもしれない」と述べている[11]。また、当時広がりつつあった浄土諸宗の進出を阻止するために苦慮しており、顕密諸宗とくに密教のなかからありうべき信仰をとりあげて、その普及と宣教に努力した[1]。

晩年は講義、説戒、坐禅修行に努め、光明真言の普及にも尽力した。寛喜3年(1231年)には、故地である紀州の施無畏寺の開基として湯浅氏に招かれた。翌寛喜4年(1232年)1月19日、弥勒の宝号を唱えながら遷化した[2]。享年60(満58歳没)。

人物[編集]

明恵は和歌にも長けており、家集『明恵上人和歌集』がある。次の短歌が知られる。

むらさきの 雲のうえへにぞ みをやどす 風にみだるる 藤をしたてて

あかあかや あかあかあかや あかあかや あかあかあかや あかあかや月

夢の世の うつつなりせば いかがせむ さめゆくほどを 待てばこそあれ(新勅撰和歌集選)

また、栄西請来の茶の種子を栂尾にまき、茶の普及の契機をなしたことは有名である[2][注釈 5]。

承久の乱で敗兵をかくまったことを機縁として、鎌倉方の総司令官として入京した六波羅探題初代長官(のちの鎌倉幕府第3代執権)北条泰時との親交がはじまっている。山本七平によれば、泰時は明恵の学徳を深く尊敬し、明恵は泰時の政治思想、とくに御成敗式目の制定の基礎となる「道理」の思想形勢に大きな影響を与えている[12]。その学徳は後鳥羽上皇・北条泰時のみならず、公家では九条兼実、九条道家、西園寺公経、武家では安達景盛、婦人では平徳子(建礼門院)など多くの人びとからの尊崇を集めた[1][5]。

明恵の非人救済神話[編集]

明恵の死後、弟子の喜海は『高山寺明恵上人行状』を書きあらわしたが、そのなかに、釈尊が衆生救済のためには、みずからの身命を顧みなかったと聞いた明恵が、16歳で登壇受戒してまもない頃、紀伊の藤代王子[注釈 6]のハンセン病患者を助けるため自己の身肉をあたえる覚悟であったという一節がある[13]。これは一種の非人救済神話といわれている[13]。

明恵の著作[編集]

おもな著書には、浄土宗をひらいた法然の『選択本願念仏集』(選択集)を読んでこれを批判した上述の『摧邪輪』(ざいじゃりん、正しくは『於一向専修宗選択集中摧邪輪』)全3巻、『同荘厳記』1巻がある。

『華厳経』で高唱される菩提心を重視した明恵は、『摧邪輪』・『同荘厳記』において、称名念仏こそが浄土往生の正業であり、もっぱら念仏を唱えることによって救われるとする法然の教説(専修念仏)に対して、その著作には大乗仏教における発菩提心(悟りを得たいと願う心)が欠けているとして、激しくこれを非難している。

40年におよぶ観行での夢想を記録した『夢記』のほか、著作は70余巻におよび、『唯心観行式』『三時三宝礼釈』『華厳仏光三昧観秘宝蔵』『華厳唯心義』『四座講式』『入解脱門義』『華厳信種義』『光明真言句義釈』などがある[1][2]。明恵の著作を収載した刊本には以下がある。

- 『明恵上人集』 久保田淳、山口明穂訳注、岩波文庫、初版1981年、改版2009年/ワイド版1994年。

- 『明恵上人伝記』 平泉洸訳注、講談社学術文庫、初版1980年

- 『日本思想大系15 鎌倉旧仏教』(岩波書店、初版1971年、新装版1995年)に、田中久夫校注「摧邪輪 巻上」と「却癈忘記」(弟子長円の筆記によるもの)

- 『日本古典文学大系83 假名法語集』(岩波書店、初版1964年)に、宮坂宥勝校注「栂尾明恵上人遺訓」

- 『大乗仏典 中国・日本篇 第20巻 栄西 明恵』(中央公論社、1988年) に、高橋秀栄(現代語訳)注解「却廃忘記」と、「光明真言土沙勧信記」

- 『日本の名著5 法然 明恵』(中央公論社、初版1971年、新版・中公バックス、1983年)に、佐藤成順(現代語訳)注解で「摧邪輪」と、「上人遺訓」

- 『明恵上人歌集 和歌文学大系60』 平野多恵注解(久保田淳監修、明治書院、2013年)。ISBN 4757601484。

明恵に関する評伝・随筆・作品研究等[編集]

- 田中久夫『明恵』吉川弘文館<人物叢書>、新装版1988年。ISBN 4642051260

- 奥田勲『明恵 遍歴と夢』東京大学出版会、1994年11月。ISBN 4130230247

- 『明恵上人 夢記訳注』奥田勲・平野多恵・前川健一編、勉誠出版、2015年2月。ISBN 4585210245。

- 紀野一義『明恵上人 静かで透明な生き方』PHP研究所、1996年10月。ISBN 4569552951。

- 『高山寺の美術 明恵上人と鳥獣戯画ゆかりの寺』高山寺監修、土屋貴裕編、吉川弘文館、2020年。ISBN 4642083839

- 以下は文学作品

- 白洲正子『明恵上人』講談社文芸文庫、1992年3月。ISBN 4061961667/新潮社(愛蔵版)、1999年11月

- 河合隼雄『明恵 夢を生きる』京都松柏社、1987年4月(法蔵館販売)。講談社<講談社α文庫>、1995年10月。ISBN 4062561182

- 光岡明『恋い明恵』文藝春秋、2005年8月。ISBN 4163673709

- 斎藤史子『清滝川 明恵・慈愛の生涯』法蔵館、2006年

- 磯部隆『華厳宗沙門 明恵の生涯』大学教育出版、2006年

- 寺林峻『小説 明恵』大法輪閣、2006年

- 上田三四二『この世この生 西行・良寛・明恵・道元』新潮社 1984年、新潮文庫、1996年。読売文学賞受賞

- 水木しげる『神秘家列伝 其ノ1』角川書店、のち「水木しげる漫画大全集」講談社。漫画

- 高瀬千図『明恵 栂尾高山寺秘話』弦書房(上・下)、2018年。ISBN 978-4863291782。

脚注[編集]

注釈[編集]

- ^ 華厳宗は、華厳経にもとづく南都六宗の一学派。奈良時代に隆盛したが平安時代にはいると勢力を失い、天暦元年(947年)に光智が華厳専修道場として東大寺尊勝院を設立してやや衰勢を取り戻したが、それ以後、再び不振に陥った。藤田(1966)p.178

- ^ これを「公請(くしょう)」と呼ぶ。松尾(1995)p.37。

- ^ このとき、明恵は文覚より、本尊として運慶作の釈迦如来像をあたえようといわれている。藤田(1966)p.178

- ^ 承久元年(1219年)には金堂が完成して快慶作の釈迦如来像が安置され、嘉禄元年(1225年)には鎮守堂、嘉禄3年(1227年)には三重塔なども建立されて明恵在世中、大門や阿弥陀堂もつくられた。藤田(1966)p.178

- ^ これにより、栂尾はのちに茶の産地となっている。

- ^ 現代の藤白神社。九十九王子のひとつ。王子とは参詣途上で儀礼を行う場所のこと。

参照[編集]

参考文献[編集]

- 藤田経世「明恵上人樹上坐禅僧像」 『日本文化史3 鎌倉時代』筑摩書房、1966年1月。

- 圭室諦成 著「明恵」、日本歴史大辞典編集委員会 編 『日本歴史大辞典9 み-わ』河出書房新社、1979年11月。

- 山本七平 『日本的革命の哲学―日本人を動かす原理』PHP研究所、1982年1月。ISBN 4569209130。

- 家永三郎 『日本文化史(第二版)』岩波書店〈岩波新書〉、1982年3月。ISBN 4-00-420187-X。

- 大隅和雄 著「南都北嶺-旧仏教の自己変革」、野上毅 編 『朝日百科日本の歴史 4中世Ⅰ』朝日新聞社、1989年4月。ISBN 4-02-380007-4。

- 松尾剛次 『鎌倉新仏教の誕生』講談社〈講談社現代新書〉、1995年10月。ISBN 4-06-149273-X。

- 網野善彦 『日本社会の歴史(中)』岩波書店〈岩波新書〉、1997年7月。ISBN 4-00-430501-2。

- 町田宗鳳 『法然対明恵 鎌倉仏教の宗教対立』講談社〈講談社選書メチエ〉、1998年10月。ISBN 4062581418。

- 納冨常天 著「明恵」、小学館 編 『日本大百科全書』小学館〈スーパーニッポニカProfessional Win版〉、2004年2月。ISBN 4099067459。

関連項目[編集]

The Buddhist Priest Myoe

A Life of Dreams

Hayao Kawai

The Lapis Press: California, 1992.

259 pp., $30.00 (cloth).

Returning in 1992 to my California sangha after two years in Japan, I was struck by the strong disjunction in approach to practice in the different cultures. I came to feel this shift as being from Japanese Faith Buddhism to an American Jungian Buddhism, informed by unavoidable therapeutic preoccupations. The Buddhist Priest Myoe: A Life of Dreams, a psychological biography of the Japanese monk Myoe Koben (1173-1232) written by the prominent Japanese Jungian psychoanalyst Hayao Kawai, bridges this cultural gap by focusing on Myoe’s extraordinary dream diary.

Myoe is fully worthy of being noted alongside his more famous contemporaries of the Kamakura Period, such as Pure Land founders Honen, Shinran, and Ippen; Zen founders Eisai and Dogen; and Nichiren; as well as with other great figures of Japanese Buddhism before and since. Unlike his contemporaries who founded new schools and lineages in a period of social and religious upheaval, Myoe’s allegiance lay in revitalizing both the traditional Shingon School (Japanese Vajrayana) and also the Kegon School based on the Flower Ornament Sutra (Sanskrit, Avatamsaka; Chinese, Huayen). This sutra, emphasizing interconnectedness, has received due attention from Western Buddhists for its visionary power and relevance to ecological concerns. Much of Myoe’s writing focuses on making the wonder and richness of its teaching practical for everyday life. His love of nature is exemplified by a famous picture of him on his meditation seat up in a tree near his temple, and by the letter he addressed to a favorite island, which he had a disciple deliver by casting it to the wind upon reaching shore.

Myoe is best remembered in Japan as a model monk who impeccably demonstrated total devotion. His motto, summarizing all Buddhist precepts and practice, was, “To be as one should be” or “To act appropriately.” His final words, the culmination of a serene deathwatch surrounded by loving disciples: “I come from among those who maintained the precepts.”

Most important, from Kawai’s Jungian perspective, Myoe kept a dream diary for forty years, from age nineteen until his death at fifty-nine. An important dream, about his wet-nurse’s corpse, was even recorded at the age of eight, after he entered temple life the year after his parents died. Kawai calls this diary “a rare phenomenon in the spiritual legacy of humanity.” Although others have kept extended dream records, Myoe added commentary, uniquely demonstrating insight into the dreams’ continuity and relationship. He was able to confront his dream material directly and use it to further his own spiritual development, even reevaluating dreams years later. The dream record, including some visions arising during meditation, clearly reveals to Kawai a process of psychological integration, or individuation, to use Jung’s term.

Kawai depicts Myoe’s Buddhist practice in the context of personal psychological fulfillment, notable in that Buddhist awakening experience and personality maturation do not always seem to coincide. Through detailed analysis of Myoe’s dreams, continuing themes are traced, especially the development of relatedness to female figures, as well as a progression of visions of buddhas, bodhisattvas, and other spiritual Images.

Kawai provides helpful background in the use and understanding of dreams in Buddhism and in Japanese culture, as well as some historical overview of Myoe’s time and Buddhist doctrinal context. He also discusses basic principles of modern dream analysis and dynamics, acknowledging the limitations of his analysis of Myoe, necessarily based on historical records without personal interviews. Occasionally, he quite confidently offers generalizations and neat interpretations of dreams to support his thesis, when the material might suggest differing viewpoints. Although Kawai’s interest in Buddhism is relatively recent, inspired by Myoe, his assurance in his dream interpretations is based on many years of analytical work with patients. Despite its conjectural nature, his argument as a whole seems productive.

Kawai describes Japanese culture as maternal: all-embracing, receptive, and unifying, while the West is paternal: discriminating, categorizing, and conceptual. He considers Myoe a rare example of someone who has integrated both principles. Butsugen-Butsumo, “Buddha Eye, Mother of the Buddhas,” a female deity, was Myoe’s object of devotional practice, along with Shakyamuni, the historical Buddha. They acted as mother and father in Myoe’s psyche, replacing the parents lost in childhood.

Myoe’s devotion first took the form of desire for self-abandonment in his early teens. He lay overnight in a charnel ground contemplating Buddha, vainly waiting for wolves to devour him as an offering, a wish later fulfilled in a vivid dream. At age twenty-three, Myoe’s drive to prove his sincere dedication led him to cut off his right ear. Unlike Van Gogh, Myoe did not act impulsively: after deliberating, he decided that his ability to study and practice the dharma would not be impaired, as it would with alternative sacrifices: eye, nose, or hand. This resolute self-initiation expressed his sorrow at not being able to hear the teachings of Shakyamuni directly. Later, he twice unsuccessfully tried to arrange pilgrimages to India.

Kawai traces the development of Myoe’s “feminine side,” using the maternal/anima schema of female archetypes used by the Jungian analyst Eric Neumann. Myoe’s female dream images gradually changed from maternal to younger anima figures, with increasing physical and emotional intimacy. This psychic partnership with women is highly unusual among Japanese men, who Kawai states are oriented strongly to the maternal. While strictly maintaining the traditional celibacy precept, Myoe did not reject sexuality or the feminine. In a dream, Myoe was transmitted a sutra affirming sexual desire as part of the bodhisattva realm. He wrote of the necessity of “familial” love based on desire, as a foundation for mature love of the Teaching. Myoe “had a deep and authentic relation with women in his inner life,” and dreamed of the cosmic Buddha Vairochana as a dignified, beautiful queen. Outwardly, he also had many women students and supporters, and built a temple as a sanctuary for widows on the losing side in his era’s bloody civil wars.

Kawai stresses that Myoe’s erotic dreams while maintaining celibacy bespeak not repressed sexuality but rather full acknowledgement of women alongside his commitment to traditional precepts. Most Japanese monks, earlier and at Myoe’s time, either had covert sexual relations or completely rejected both sexuality and women. For Kawai, the latter monks’ souls had died; they had not truly maintained the precepts since they did not need them.

Fascinatingly, Kawai compares Myoe’s attitude toward women with that of his contemporary Shinran, the Pure Land founder. After his own spiritual crisis over sexual desire, Shinran’s solution, inspired by a vision of the Bodhisattva of Compassion, was an intense transcendent faith that allowed him to establish an openly married clergy. Eventually all of Japanese Buddhism has followed suit. Although their responses seem diametrically opposed, Kawai highly praises Myoe and Shinran as the two Japanese Buddhist leaders of their time who evidently faced the issue of sexuality directly. However, while this matter was much more central to Myoe and Shinran, one may note that others of their contemporaries had women students, and some (e.g. Dogen) even wrote of women’s equal capacity for awakening.

Kawai’s detailed Jungian outlook helps further our understanding of the possible relationship between personality development and the bodhisattva path. Though Kawai examines Myoe’s inspiring life and dreams somewhat from the standpoint of Huayen dialectics, much more study would be welcomed.

George Tanabe Jr.’s recent Myoe the Dreamkeeper: Fantasy and Knowledge in Early Kamakura Buddhism(Harvard University Press, 1992) includes a complete translation of the substantial extant portions of Myoe’s “dream diary,” as well as details of the history of his time and Huayen philosophical context. Tanabe focuses on Myoe’s dreaming, but from the standpoint of fantasy as the basis of Buddhist hermeneutics and literature, seeing dreams and meditative visions as expressions of emotion rather than objects for psychological interpretation. Myoe’s extraordinary career included many fascinating aspects, beyond what can be noted here. These books provide a rich introduction.

Taigen Daniel Leighton, a Zen priest, is co-translator of Cultivating the Empty Field: The Silent Illumination of Zen Master Hongzhi (Northpoint Press)