The Way to Divine Knowledge

The Way to Divine Knowledge was written by William Law (1686-1761) as preparatory to a new edition of the Works of Jacob Behmen and the “Right Use of Them”. The first edition of The Way to Divine Knowledge was printed in 1752 by the London printer and novelist Samuel Richardson, who very much admired William Law and had been involved in printing Law’s earlier books. It was published in London by the distinguished booksellers William Innys and John Richardson (not related to Samuel Richardson).[1] It was preceded by The Spirit of Prayer (part I, 1749, and part II, 1750) and followed by The Spirit of Love (part I, 1752, and part II, 1754).

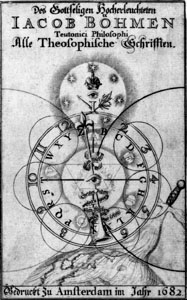

The Way to Divine Knowledge was partly written by William Law as a defence against accusations of Enthusiasm by his opponents, but it was also written in order to assist Law’s contemporary readers to a better understanding of the works of Jakob Boehme (1575-1624), a German philosopher and Christian mystic within the Lutheran tradition. The reading of Boehme’s works had deeply moved William Law.[2] [3] The German editions of Boehme’s works appeared between 1612 and 1624, the year of his death, and the sixth year into the Thirty Years’ War, an extremely destructive conflict in Central Europe between 1618-1648, which had initially been a war between various Catholic and Protestant states, but which was actually rather a war fought for political superiority. It was ended by the Peace of Westphalia in 1648.

The English translations of Boehme’s works by John Sparrow and John Ellistone appeared between 1645 and 1662 during the upheaval of the English Civil War (1642-1651) and the trial and execution of King Charles I. Even though Law appreciated the quality of the seventeenth-century English translations, he had taught himself the German language in order to be able to read Boehme in the original language. Law himself lived in the Age of Enlightenment centering on reason in which there were many controversies between Catholics and Protestants, Deists, Socinians, Arians etc. which caused conflicts that worried Law, who as a pacifist rejected all wars and every form of violence.

Some people very much admired Law’s “mystical” writings, such as his contemporaries Samuel Richardson, George Cheyne and John Byrom, and even the Methodist Charles Wesley appreciated his works, whereas some people such as William Warburton and the Methodist John Wesley, the brother of Charles Wesley, deeply disliked Law’s “mystical” works. John Byrom, who greatly admired William Law, wrote a poem on the Way to Divine Knowledge, which was called ”A Dialogue between Rusticus, Theophilus, and Academicus, on the Nature, Power, and Use of Human Learning in Matters of Religion, from Mr. Law’s Way to Divine Knowledge”. This poem was published in 1773 in Byrom’s collected works Miscellaneous Poems.[4] All of Law’s books were collected by John Byrom as can be found in the catalogue of his library.[5] William Wilberforce (1759-1833), the politician, philanthropist and leader of the movement to stop the slave trade, was deeply touched by reading William Law books. Another admirer was John Henry Overton (1835–1903), the English cleric and church historian who published in 1878 The English Church in the Eighteenth Century. In 1881 Overton published William Law, Nonjuror and Mystic. In the twentieth century Stephen Hobhouse (1881-1961), the prominent English peace activist and distinguished religious writer, and Aldous Huxley (1894-1963), the English writer and philosopher, among many others greatly admired Law’s writings, especially the mystically inclined works.

Introduction of The Way to Divine Knowledge[edit]

In The Way to Divine Knowledge William Law dealt with Boehme’s writings focussing on the “religion of the heart”. It was most probably the absence of “book learning” in Boehme’s works which must have been one of the reasons of Law’s fascination for Boehme. [6] According to some, William Law had been considering to publish a new edition of the works of Jakob Boehme which would help readers to make the “right use of them”. However, in The Way to Divine Knowledge it becomes clear that Law had no real intention of doing so.[7] Law also mentioned several possibly bewildering passages in Jakob Boehme’s books and Law’s advice was to skip these passages as Boehme’s works were often obscured by the “physico-chemical, medical, alchemistic, and astrological language. [8] John Sparrow, one of the main English translators of Boehme’s works voiced similar reservations: “Words are vehicula rerum ... the bare letter of [Boehme’s] writings ... though exactly translated, will not give a man the understanding of them ... unless the spirit of regeneration in Christ [enters into him].[9]

The Way to Divine Knowledge consists of three dialogues between Theophilus, Humanus, Academicus and Rusticus. These three dialogues are a continuation of Part II of Law’s earlier book The Spirit of Prayer (Part I of 1749 and Part II of 1750). The exchanges between the four men are essential to the understanding of Law’s objectives. The Way to Divine Knowledge is filled with beautiful prose, tolerance and charm. It also has some humorous passages as shown in some of the following passages.

Theophilus, Humanus, Academicus and Rusticus[edit]

The three dialogues between Theophilus, Humanus, Academicus and Rusticus are the means by which Law conveyed his views. Theophilus represents the “Love of God” or “Friend of God” and voices the views of William Law himself. [10] Humanus is the “learned unbeliever” and represents the deists (also referred to as the “infidels”)[11] [12] who had been raised as Christians, but who had doubts as to the Trinity, as well as with orthodox teachings and with the supernatural interpretations of miracles. Academicus represents the intellectuals and their close study of Latin, Greek or even Hebrew literary texts which enabled them to discuss fine points of historical and theological differences. Academicus is hampered by this “letter learning”. Rusticus represents the simple, honest man living among shepherds herding livestock. Even though he is unable to read or write, he is much more able to receive “the truth” than Academicus or Humanus.

The Atonement or The Necessity of Regeneration or the New Birth[edit]

The core subject in The Way to Divine Knowledge is the concept of the “new birth” (regeneration) within the soul. In the Atonement passages in The Way to Divine Knowledge Law again asserted, as he had done in his previous books especially from 1737 and onwards, that the redemption of Christ was an example of “God’s mercy to all mankind”. It was the only method of overcoming evil achieved by a new birth of a new sinless life in the soul and its reunion with God. This new birth depended on one’s own will to choose between “good and evil” which would create either heaven (good, love and light) or hell (anger, wrath and darkness) within one’s soul.[13] However, Law realized that this concept of “the nature and necessity of regeneration” would be totally rejected by those who believed in “guilt, righteous anger, retributive punishment, compensatory justice and sacrificial death. [14] Law compared the rebirth with the two parables of the hidden treasure and the pearl of great price (Matt. 13, 44-6), which was Boehme’s “noble pearl of wisdom” or Sophia, see the paragraph below.[15]

First Dialogue[edit]

The first dialogue took place in the morning. Humanus opened the dialogue. It was the first time that he had been allowed to enter into the conversation, because he had given up all “cavilling and disputing” for which Theophilus was indeed very grateful. So Humanus is now a “convert ... [who is] all hunger and thirst after this new light, a glimpse of which has already raised [him] as it were from the dead.[16]

The Test of Truth[edit]

Theophilus explains that ”the “test of truth” lies in finding out whether it is truly the Spirit of God and the Love of God, the pure, free, universal goodness of God that one longs for.[17][18] Theophilus argues that “the fall of man into the life and state of this world is the whole ground of his redemption, and that a real birth of Christ in the soul is the whole nature of it”.[19] That is the reason why one should look up “in faith and hope to God as our Father and to Heaven as our native country” and why we are only “strangers and pilgrims upon earth”.[20] Theophilus argues that Humanus, now a convert, should not try to propagate Christianity or make converts himself, for if there is no “sensibility of the evil and burden and vanity of the natural state, we are to leave people to themselves in their natural state, till some good providence awakens them out of it” for Deism (or infidelity) is merely caused by the bad state of Christendom and the “miserable use that heathenish learning and worldly policy have made of the Gospel”.[21] Humanus added:

Disciples of Epicurus[edit]

Theophilus was very pleased with the progress Humanus had made, especially with his resolution not to enter into debate about the Gospel doctrines with his [old Brethren] till they were ready for it and wanted to be saved and if that time should never come Humanus must consider them as disciples of Epicurus:

The Second Dialogue[edit]

The second dialogue took place in the afternoon of the same day. It opened with Academicus admitting rather peevishly that he was somewhat disappointed. He had come expecting to hear everything he wanted to know about Jakob Boehme and his works, but so far Boehme had not even come up in the conversation.

How to Understand Jakob Boehme[edit]

Academicus found Boehme totally unintelligible and so did all his friends, he added. He thought that Theophilus would publish a new edition of Boehme’s works removing “most of his strange and unintelligible words and give us notes and explications of such as you do not alter”. Then Rusticus stepped in, representing Law’s view of skipping over several possibly bewildering passages in Jakob Boehme’s books. Rusticus admonished Academicus by telling him about his neighbour John the Shepherd and his wife Betty:

Rusticus added another little story of John the Shepherd. The squire’s wife had given John the Shepherd and his wife Betty a huge book with commentaries on the New Testament, but John got so bewildered with all those fancy notions when Betty read it to him, that he asked Betty to bring the book back immediately. For John had rather the feeling of the gospel in his heart even if he did not understand it all than all those difficult explanations of the head (of learned men).[25]

Rusticus was clearly annoyed with the impatience of Academicus for to understand the “truths of Jacob Behmen” one must stand where he stood, where he began and seek only the heart of God. He accused Academicus that he wanted to “stand upon the top of [Boehme’s] ladder without the trouble of beginning at the bottom and going up step by step.[26] This in turn annoyed Academicus who said that renouncing all his learning and reason if he was to understand Jacob Behmen was something which he was not resolved to purchase at so high a price. To this Theophilus answered:

Universal Redemption Open to Everyone[edit]

Theophilus had explained to Academicus that the redemption is possible for everyone who has their inward man “kindled into love, hope and faith in God” and who is capable of the highest divine illumination, while “learned students full of art and science can live and die without the least true knowledge of God and Christ”:

Seventeen Hundred Years of Learning[edit]

Academicus explained how he had followed the advice of so many counsellors and had been “sweating for some years” till Rusticus told him that if he had lived “seventeen hundred years ago” he had stood in just the place as Rusticus himself stood now. For Rusticus could not read and all these “hundreds of thousands of disputed books and doctrine books which these seventeen hundred years had produced, stood not in [his] way”.[29] Academicus had been reading “cart-loads of lexicons, critics and commentators upon the Hebrew Bible”, books on Church History, all the councils and canons made in every age, Calvin and Cranmer, Chillingworth and Locke, the discourses of Mr. Boyle and Lady Moyer’s lectures, the Clementine constitutions, dr. Clarke and mr. Whiston might be useful, all the Arian and Socinian writers, all the histories of the rise and progress of heresies and of the lives and characters of the heretics, etc., a list of some of the books in Law’s own library.[30] Academicus was deeply grateful for “this simple instruction of honest Master Rusticus”.[31] Academicus had now given up his wish that someone would make a new translation of Boehme’s works in English with comments etc., but nevertheless he still would want someone to make Boehme more plain and intelligible.

Theophilus subsequently explained that there are two sorts of people to whom Boehme forbids the use of his books. The first sort are those who are not seeking a new birth, for Boehme requires his readers to be in the state of the “returning prodigal son”. The others are the “men of reason” who only look to the light of reason as the true “touchstone of divine truths”.[32] Consequently, it was useless for Academicus to ask Theophilus or anyone else to help him to understand Boehme’s works.

The Philosopher’s Stone[edit]

The concept of the “Philosopher’s Stone” had intrigued many readers ever since Boehme wrote his books between 1612 and 1624, the year of his death. Theophilus explained that when Boehme’s works first appeared in English from 1645 onwards many people of “the greatest wit and abilities” had read his books, but instead of entering into “his one only design” which was their own “regeneration from an earthly to an heavenly life” they became chemists and “set up furnaces” to regenerate metals in search of the Philosopher’s Stone.[33] They did this all in vain because:

The Great Delusion of Knowledge[edit]

Theophilus said that to count the stars or to observe their positions or motions is of the same natural knowledge (natural philosophy) as when a shepherd counts his sheep and observes their time of breeding. The rational man can reason and dispute about the outward causes and effects, but the “mystery of eternal nature” (different from our temporal nature, for temporal nature is concerned with time and place) was that which Boehme had found opened in himself.[35] Unfortunately, so Theophilus continued, we call everything knowledge “that the reason, wit or humour of man prompts him to discourse about”, whether it is fiction, conjecture, report, history, criticism, rhetoric or oratory. All this passes for “sterling knowledge”, whereas it is only the “activity of reason playing with its own empty notions”.[36] This was according to Theophilus the great delusion which had overspread the Christian world and all countries and libraries were the proof of it:

The Pearl of Great Value[edit]

Theophilus stated that the “only way to divine knowledge is the way of the gospel” which calls and leads us to a “new birth of the divine nature brought forth in us”.[38] He compared the divine knowledge with a wonderful pearl, the pearl of great value or wisdom, that is hidden in the “ground of a certain field” and explained to Academicus that this pearl refers to the new birth which could only be achieved by changing one’s will to find it. For nothing, so argued Theophilus, generates either life or death in you, but the working of your own mind, will and desire. If Academicus continued to follow his earthly will then every step would be a departure from God, because this earthly will is ruled by “pride, self-exaltation, in envy and wrath, in hatred and ill-will, in deceit, hypocrisy and falseness, ... working with the devil”. When one works with the devil, the nature of the devil is created in oneself which leads to the “kingdom of hell”.[39] So, Theophilus continued:

The Grossness of Idolatry[edit]

According to Theophilus, God is no outward or separate being. The religion of reason, which Academicus represented, considers redemption as “obtaining a pardon from a prince”. This has all the “mistakes, error and ignorance of God” which is found in idolatry:

With the above words Theophilus put an end to the second dialogue and suggested that they would have a few days rest to “purify the heart”.

The Third Dialogue[edit]

The third dialogue took place a couple of days later. Theophilus started the dialogue with repeating that Academicus’ own reason was the most powerful enemy of religion and that “men of speculative reason” of whom Academicus was so afraid are powerless enemies:

The Concept of the Seven Properties of Nature[edit]

Theophilus argued in the third dialogue that the dark ternary of attraction, resistance and whirling became the ground of the “threefold materiality of earth, water and air (“an anguishing materiality”) out of which came the fourth property of nature as a “globe of fire and light” as the “true outbirth of the eternal fire”. Since this eternal fire is not a “moveable thing” and stands forever “in the midst of the seven properties” so the sun as the “true outburst of the eternal fire” is not a moveable thing and is therefore the centre and heart of the whole system, forever separating the first three properties from the three that follow, and thus changing the “three first forms of material wrath into the three last properties of the Kingdom of Heaven”.[43][44] Theophilus saw the sun as a place that gives forth fire and light “till all material nature is dissolved”.[45]

Stephen Hobhouse (1881-1961) stated that for many readers of Law’s works the concept of the seven properties of nature had been bewildering and therefore his advice was to skip these passages. It is a concept found in Boehme’s works which relates to a division into a “dark ternary”[46] and a “light ternary” divided by a fourth property of fire or lightning (3 + 1 + 3).[47] Hobhouse wrote that Law’s sevenfold scheme did not fit in easily with Law’s usual idea of the Trinity in man and God, but he suggested that Law may have been influenced by his belief that Newton had been a “secret disciple of Boehme” and that Newton had learned from Boehme the theory of gravitation and the laws of celestial mechanics.[48][49]

A New English Edition of Boehme’s Works[edit]

Theophilus had given Academicus all the answers on how to understand Boehme’s works. Upon Academicus’ question as to when a new English edition of all Boehme’s works would be published, or if not all then at least which book of Boehme would be published first, Theophilus answered that two or three of Boehme’s books would be enough to open the “grounds of the whole mystery of the Christian redemption”. For even Boehme himself had thought that he had written too many books and rather wanted them all to be reduced into one. It had been Boehme’s frequent repetition of “one and the same ground”, Theophilus states, which had been the cause of so many volumes. What is found in one of Boehme’s books is also found in other books, so, according to Theophilus, there was absolutely no need to go through all his books.[50]

All the Controversies of the Church from Augustine to the Socinians and Deists[edit]

Theophilus ended the third dialogue by returning to the cause of all the controversies of the Church, beginning with St. Austugine and Pelagius who in the fifth century A.D. wrangled about the freedom of the human will, followed by the horrible wars as the result from different interpretations of the Gospel between Catholics and Protestants. From there on Theophilus continued with the controversy between the Socinians and their opponents about “the Fall, original sin, its guilt, the vindictive wrath of God and the necessity of satisfying the divine justice, the necessity of the incarnation, sufferings, death and satisfaction of Christ ”, which were all tried at the “bar of reason” with each of them defending themselves that the “soul and everything else was created out of nothing”.[52] This “vanity and blindness of the dispute”, argued Theophilus, could only lead to indifference and infidelity in the hearts of men.[53] All controversy, both within and outside of the Church, was vain, according to Theophilus. What Boehme wrote did not alter the Gospel-doctrine, nor added anything to it. It disturbed no one who was in possession of the truth, drove to nothing but to the “opening of the heavenly life in the soul”:

And with these words Theophilus ended The Way to Divine Knowledge.

Reception of The Way to Divine Knowledge[edit]

The Way to Divine Knowledge rather than helping to understand the philosophy of Jakob Boehme almost reads like a defence by Law (as Theophilus) against the attacks upon his mystically inclined works, which some critics, represented by Humanus and Academicus, found unorthodox. Indeed, Law’s later works from 1737 and onwards were rather more controversial, because of their mystical content caused by the influence of especially Jakob Boehme. Of all of Law’s works the most widely appreciated by his contemporaries and those of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries were the ones written before 1737, especially A Practical Treatise upon Christian Perfection (1726) and A Serious Call to a Devout and Holy Life (1729).

References[edit]

- Hobhouse, Stephen, Selected Mystical Writings of William Law, (1938), Rockliff, London, 1949.

- Joling-van der Sar, Gerda J., The Spiritual Side of Samuel Richardson, Mysticism, Behmenism and Millenarianism in an Eighteenth-Century English Novelist, 2003.

- Keith Walker, A., William Law: His Life and Thought, SPCK, The Camelot Press Ltd., London, 1973.

- Law, William Law, The Way to Divine Knowledge, 1752 (first edition), 1762 (second edition), 1778 (third edition).

- Law, William, The Works of William Law, 9 volumes, G. Moreton in 1892-93 (a reprint of the “1762” edition of The Works of William Law, published in nine volumes).

- Mullett, Charles F., The Letters of Doctor George Cheyne to Samuel Richardson (1733-1743), Vol. XVIII, No. 1, Columbia, 1943.

- Overton, John Henry, William Law, Nonjuror and Mystic, Longmans, Green and Co., London, 1881.

- Weeks, Andrew, Boehme, An Intellectual Biography of the Seventeenth-Century Philosopher and Mystic, New York, 1991.

Notes[edit]

- ^ Gerda J.Joling-van der Sar, The Spiritual Side of Samuel Richardson, Mysticism, Behmenism and Millenarianism in an Eighteenth-Century English Novelist, 2003, pp 118-120.

- ^ Gerda J.Joling-van der Sar, The Spiritual Side of Samuel Richardson, Mysticism, Behmenism and Millenarianism in an Eighteenth-Century English Novelist, 2003, pp 142 ff.

- ^ Andrew Weeks, Boehme, An Intellectual Biography of the Seventeenth-Century Philosopher and Mystic, New York, 1991.

- ^ Miscellaneous Poems, Vol. II, p. 88.

- ^ A Catalogue of the Library of the Late John Byrom. https://archive.org/details/acataloguelibra00roddgoog/page/n139

- ^ Stephen Hobhouse, Selected Mystical Writings of William Law, 1949, p. 269.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, Works, Vol. 7, pp. 195; 198. Theophilus, see the next paragraph below, says that “the true understanding must come from the inward ground [soul]” and that this is the reason why Academicus must understand how needless it is to ask [Theophilus] or anyone else to help Academicus to understand Boehme.

- ^ Stephen Hobhouse, Selected Mystical Writings of William Law, 1949, pp. 345; 357.

- ^ Gerda J. Joling-van der Sar, The Spiritual Side of Samuel Richardson, Mysticism, Behmenism and Millenarianism in an Eighteenth-Century English Novelist, footnote 405, p. 134.

- ^ Stephen Hobhouse quoting the words of John Henry Overton in Selected Mystical Writings of William Law, 1949, p. 263.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, Works, Vol. 7: “Reason is the vain idol of modern deism and modern Christianity”, p. 168.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, Works, Vol. 7: “This is the ... depth of ... deism or infidelity”, p. 178.

- ^ Boehme wrote in the Forty Questions that “every soul is its own judgment” and Law had written in The Spirit of Prayer, part I (1749), “A Christ not in us is the same thing as a Christ not ours”, Stephen Hobhouse, Selected Mystical Writings of William Law, 1949, p. iv.

- ^ See also Stephen Hobhouse, Selected Mystical Writings of William Law, 1949, p. 299.

- ^ Stephen Hobhouse, Selected Mystical Writings of William Law, 1949, p. 259.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, The Works, Vol. VII, p. 148.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, The Works, Vol. VII, p. 150.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, The Works, Vol. VII, p. 156.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, The Works, Vol. VII, p. 164.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, The Works, Vol. VII, p. 170.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, The Works, Vol. VII, pp. 176; 177.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, The Works, Vol. VII, p. 179.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, The Works, Vol. VII, pp. 181; 183-184.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, The Works, Vol. VII, p. 185.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, The Works, Vol. VII, p. 186.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, The Works, Vol. VII, p. 189.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, The Works, Vol. VII, pp. 189-191.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, The Works, Vol. VII, pp. 191-192.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, The Works, Vol. VII, pp. 192-194.

- ^ Stephen Hobhouse on Law’s Library, Selected Mystical Writings of William Law, 1949, pp. 355-357; 361-367.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, The Works, Vol. VII, p. 194.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, The Works, Vol. VII, pp. 195-196.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, The Works, Vol. VII, pp. 195-196.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, The Works, Vol. VII, p. 196.

- ^ Stephen Hobhouse, Selected Mystical Writings of William Law, 1949, p. 308.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, The Works, Vol. VII, pp. 202-203.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, The Works, Vol. VII, pp. 203; 205-206

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, The Works, Vol. VII, p. 208.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, The Works, Vol. VII, p. 210.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, The Works, Vol. VII, pp. 211; 218; 219.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, The Works, Vol. VII, pp. 229-230.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, The Works, Vol. VII, pp. 231-232.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, The Works, Vol. VII, pp. 245.

- ^ Gerda J. Joling-van der Sar, The Spiritual Side of Samuel Richardson, Mysticism, Behmenism and Millenarianism in an Eighteenth-Century English Novelist, 2003, pp. 132-133.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, The Works, Vol. VII, p. 246

- ^ ”Ternary” from Latin ternarius means composed of three items.

- ^ Stephen Hobhouse, Selected Mystical Writings of William Law, pp. 344-345.

- ^ Stephen Hobhouse, Selected Mystical Writings of William Law, p. 346.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, The Works, Vol. VII, pp. 250-251.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, The Works, Vol. VII, p. 254.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, The Works, Vol. VII, pp. 255-256.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, The Works, Vol. VII, p. 259.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, The Works, Vol. VII, p. 260.

- ^ The Way to Divine Knowledge, The Works, Vol. VII, pp. 261-262.