Rethinking William Penn

January 1, 2022

By Trudy Bayer

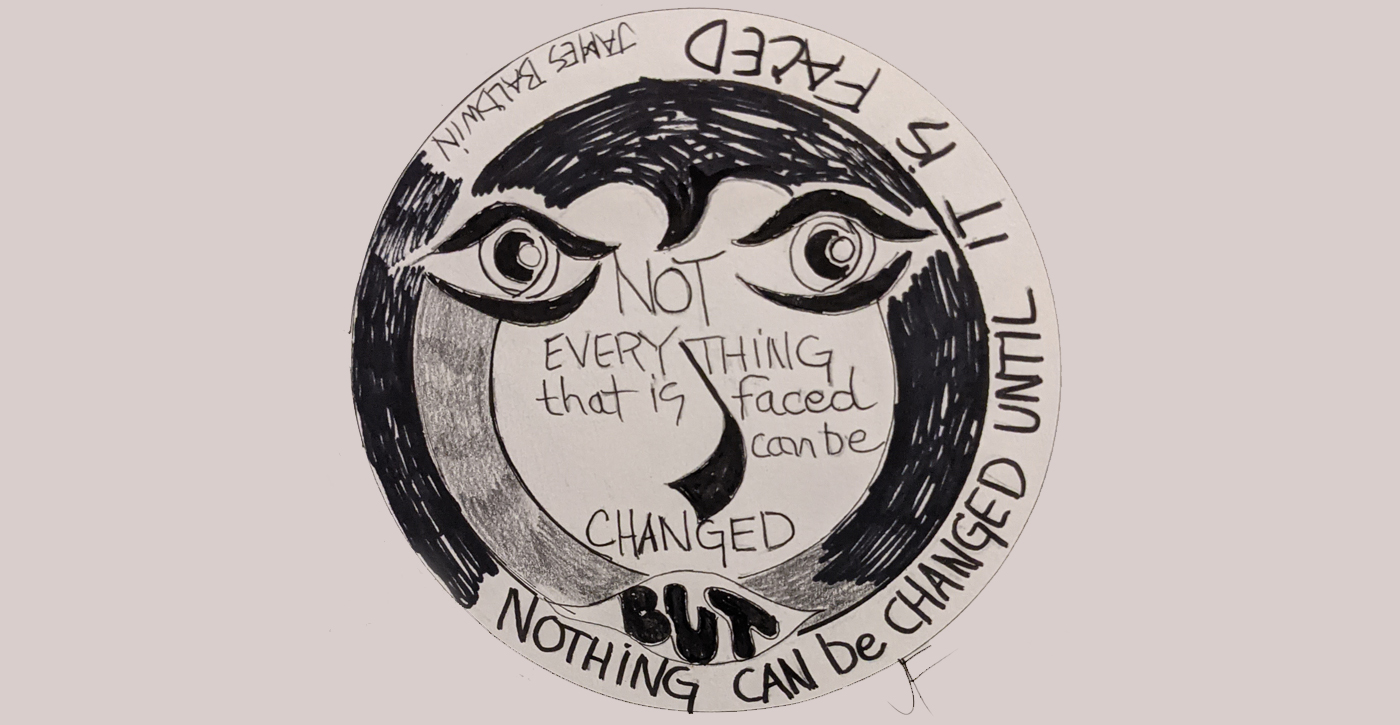

Illustration of James Baldwin quote, “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced,” by Jill Flynn.

A Path to Retrospective Justice

William Penn is the most widely recognized Quaker in U.S. history, in no small part due to his settling the colony of Pennsylvania and to the Quaker Oats Company’s 1909 decision to appropriate his image to use on its iconic oatmeal box (since the late 1950s it has used a more generic colonial Quaker). As a child, I was struck by that image as well as by illustrations of Penn in our Pennsylvania history books. What a benevolent-looking man; what odd clothing; and most of all, what unusual beliefs! Penn was unlike so many of the other men we studied who were excused for exploiting Native Americans and breaking treaties with them. In contrast, Penn was portrayed as a friend and advocate to native people, particularly the Lenape, from whom he acquired the land where he founded Philadelphia. But it was his novel Quaker beliefs—that there is that of God in each of us, and that we can directly access the Divine—that left the biggest impression on me. His unwavering commitment to these beliefs in the face of ridicule and persecution was inspiring. Many years later when I joined the Religious Society of Friends, I was not at all surprised to find so many Quaker organizations bearing this hero’s name.

However, what most history books and encyclopedic narratives omitted or minimized was Penn’s role in the transatlantic slave trade. And it is this dimension of his legacy—and subsequently our own—that is under increasing scrutiny, thanks to the spotlight Black Lives Matter has cast on the relics and symbols of slavery we still commemorate. Consequently, how we continue to memorialize William Penn now taps at the conscience of every Quaker entity bearing his name.

Friends Committee on National Legislation (FCNL) has responded to this query by changing the name of its Capitol Hill center from the William Penn House to Friends Place on Capitol Hill. This decision and the change it represents is a concern for many Friends. Primarily, they feel Penn is being unfairly judged when today’s “woke” values are applied to a man who lived centuries ago. As a result, they see Penn as another casualty of contemporary “cancel culture,” the tendency to remove and cancel public figures and other entities for behaviors we today judge as wrong.

I have consistently heard vocal ministry on the dangers of judging Penn by today’s standards. Yes, Penn was a slaveholder, but his slaveholding was the product and expression of his historical period and can only be understood and judged within that context. On multiple occasions, I have heard this historical explanation of Penn and slavery: White, wealthy, propertied men owned slaves. That’s what they did.

But are these statements accurate? What are the documented facts of the historical record? Would an honest accounting of the historical record alter our understanding of Penn’s role as a Quaker slaveholder? Is there a process whereby we can more fully discern the deeds of our ancestors?

Harold D. Weaver Jr.’s three-step plan for retrospective justice suggests a process to answer these questions. Weaver’s plan is adapted from the 2006 seminal publication by Brown University researchers on Slavery and Justice in which they identify three steps essential in retrospective justice. Weaver adapts these steps to offer a plan whereby Friends can acknowledge and document our participation in chattel slavery, and through this process build a more just society. Retrospective justice refers to:

attempts to administer justice decades or centuries after the commission of a severe injustice or series of injustices against persons, communities, nations or ethnic groups—in this case, a series of continuous historical events, including the Transatlantic slave trade, chattel slavery, and the legacy of continued oppression, exploitation, and humiliation through Jim Crow against people of African descent in the Unites States.

Retrospective justice involves: (1) formal acknowledgement of an offense, (2) a commitment to truth telling, and (3) making amends. Weaver’s model informs an understanding of the recent conflict surrounding William Penn.

There is little disagreement that Quakers were direct participants and profiters of slavery. But acknowledging this offense is usually accompanied with equal or greater emphasis on Quaker abolitionists. Vocal ministry that I have heard about recognizing and responding to the transgressions of Penn and other Quaker slaveholders is nearly always met with rejoinders emphasizing the groundbreaking role Quakers played in ending slavery, blending these two entirely unrelated matters. Shifting the focus away from the actual offense that many Quakers, like Penn, proliferated and profited from chattel slavery interferes with a clear, unequivocal acknowledgement of it. Brown University researchers observed this same reluctance to focus on and acknowledge the real offense across the very wide range of organizations and groups they studied. “Every confrontation with historical injustice begins with establishing and upholding the truth, against the inevitable tendencies to deny, extenuate, and forget.”

The second step towards retrospective justice, a commitment to truth telling, requires examining information about the offense honestly and documenting this information in the historical record and cultural memory of the respective group. How accurate are some of the common narratives about Penn and slavery, and do these narratives provide an honest account?

The dominant narrative accounting for Penn’s slaveholding is that he was a product of his historical moment, reflecting the norms and legal practices of his time. White, wealthy men owned slaves. However, this narrative does not comport with the facts. Penn was among a scant seven percent of Philadelphians who owned slaves. Among his fellow Quakers in Penn’s Woods, he was even more of an anomaly. In 1688, the nearby Germantown Meeting issued a “Petition Against Slavery,” indicting the evil institution, demanding its immediate abolition, and calling for universal human rights. The fact is that many of Penn’s Quaker contemporaries “woke” to the horrific suffering of slavery and human bondage, despite the constraints of their historical moment, but he did not. The historical account shows that Penn actively promoted the slave trade in Pennsylvania and was himself a slaveholder. He was at the dock when the first slave ship, Isabella, arrived in Philadelphia in 1684, and he purchased some of the 150 captured Africans held aboard. Further research reveals his motive.

For Penn, slaves were essential to expanding his holy experiment and the settlement and expansion of Pennsylvania. Not only were slaves advantageous to his new colony but also lucrative to his personal wealth. Penn acknowledged his preference for owning slaves (rather than indentured servants who would eventually earn their freedom) in his correspondence with the overseer of his plantation, Pennsbury Manor: “It was better they was blacks for then a man has them while they live.”

When an offense is clearly acknowledged and accounted for, we have an opportunity to do something about it: to make amends. This may involve monetary reparations but equally entails spiritual, interpersonal, cultural, psychological, and political dimensions. It is an attempt at atonement and reconciliation. As such, it touches both the oppressor and oppressed.

On a macro level, Weaver suggests: “After learning the truth of our history, I recommend that the Society of Friends commits to the memorialization of those affected by chattel slavery, designating an annual day of remembrance.” Many meetings and Quaker organizations are beginning to acknowledge Friends’ role in the transatlantic slave trade and consider actions we may take to begin healing the injustice and trauma of this legacy, which persists to this day.

FCNL’s decision to rename its hospitality house, whether guided consciously by a retrospective justice paradigm or not, is an example of how an awareness of systemic racism and our complicity in it evolves. When the house opened in 1966, it was acceptable to FCNL to identify its presence on Capitol Hill with the name of a slaveholder; more than half a century later, it is not.

Friends who object to this decision often characterize it as another example of cancel culture. In this narrative, Penn is the victim: wrongly judged and sanctioned. His role in slavery and, most importantly, his chattel and their descendants are absent. How would this concern change if it included the casualties of Penn’s slavery and their descendants? Of course, the question is rhetorical. We know that changing the focus of our perception reorganizes the entire picture and the story we tell about it.

Friends have only recently begun to examine and acknowledge our role in slavery, not as abolitionists or visionaries on the vanguard of the struggle for human rights, but as players in perpetration of one of the most egregious and long-standing crimes against humanity. Slavery was wrong regardless of who practiced it. It caused unimaginable human suffering. It is indefensible.

Heroes cast a very long shadow on their descendants. Their stories become core components of the collective identity and shared culture of any group. Heroes symbolize our highest ideals. The question is whether we are willing to know these heroes, and thus ourselves, honestly, or whether we prefer the illusion?

William Penn was not only a slave trader. He was a champion for religious freedom and tolerance. An accurate historical account of his slaveholding cannot cancel these facts. Rather, they provide an opportunity to know Penn and ourselves more honestly, and in that process begins a clearing of a path towards retrospective justice.

Capitol Hill

process

Quakers

William Penn House

Online Features

Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

Trudy Bayer

Trudy Bayer is a member of Pittsburgh (Pa.) Meeting. She was the founding director of the Oral Communication Lab, University of Pittsburgh and is a specialist in human rights communication, the rhetoric of social movements, and Lucretia Mott. Contact: trudy.bayer84@gmail.com.