William Law

William Law | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1686 Kings Cliffe, Northamptonshire |

| Died | 9 April 1761 Kings Cliffe, Northamptonshire |

| Venerated in | Anglican Communion |

| Feast | 10 April |

William Law (1686 – 9 April 1761) was a Church of England priest who lost his position at Emmanuel College, Cambridge when his conscience would not allow him to take the required oath of allegiance to the first Hanoverian monarch, King George I. Previously William Law had given his allegiance to the House of Stuart and is sometimes considered a second-generation non-juror.

Thereafter, Law first continued as a simple priest (curate) and when that too became impossible without the required oath, Law taught privately, as well as wrote extensively.

His personal integrity, as well as his mystic and theological writing greatly influenced the evangelical movement of his day as well as Enlightenment thinkers such as the writer Dr Samuel Johnson and the historian Edward Gibbon. In 1784 William Wilberforce (1759–1833), the politician, philanthropist and leader of the movement to stop the slave trade, was deeply touched by reading William Law's book A Serious Call to a Devout and Holy Life (1729).[1] Law's spiritual writings remain in print today.

Early life[edit]

Law was born at Kings Cliffe, Northamptonshire, in 1686. In 1705 he entered Emmanuel College, Cambridge as a sizar, where he studied the classics, Hebrew, philosophy and mathematics. In 1711 he was elected fellow of his college and was ordained. He resided at Cambridge, teaching and taking occasional duty until the accession of George I, when his conscience forbade him to take the oaths of allegiance to the new government and of abjuration of the Stuarts. His Jacobitism had already been betrayed in a tripos speech. As a non-juror, he was deprived of his fellowship.[2]

For the next few years Law is said to have been a curate in London. By 1727 he lived with Edward Gibbon (1666–1736) at Putney as tutor to his son Edward, father of the historian, who says that Law became the much-honoured friend and spiritual director of the family. In the same year he accompanied his pupil to Cambridge and lived with him as governor, in term time, for the next four years. His pupil then went abroad but Law was left at Putney, where he remained in Gibbon's house for more than 10 years, acting as a religious guide not only to the family but to a number of earnest-minded people who came to consult him. The most eminent of these were the two brothers, John and Charles Wesley, John Byrom the poet, George Cheyne the Newtonian physician, and Archibald Hutcheson, MP for Hastings.[2]

The household dispersed in 1737. Law by 1740 retired to Kings Cliffe, where he had inherited from his father a house and a small property. There he was joined by Elizabeth Hutcheson, the rich widow of his old friend (who recommended on his death-bed that she place herself under Law's spiritual guidance) and Hester Gibbon, sister to his late pupil. For the next 21 years, the trio devoted themselves to worship, study and charity, until Law died on 9 April 1761.[2]

Bangorian controversy and after[edit]

The first of Law's controversial works was Three Letters to the Bishop of Bangor (1717), a contribution to the Bangorian controversy on the high church side. It was followed by Remarks on Mandeville's Fable of the Bees (1723), in which he vindicated morality; it was praised by John Sterling, and republished by F. D. Maurice. Law's Case of Reason (1732), in answer to Tindal's Christianity as old as the Creation is to some extent an anticipation of Joseph Butler's argument in the Analogy of Religion. His Letters to a Lady inclined to enter the Church of Rome are specimens of the attitude of a High Church Anglican towards Roman Catholicism.[2]

Writings on practical divinity[edit]

A Serious Call to a Devout and Holy Life (1729), together with its predecessor, A Practical Treatise Upon Christian Perfection (1726), deeply influenced the chief actors in the great Evangelical revival.[3] John and Charles Wesley, George Whitefield, Henry Venn, Thomas Scott, and Thomas Adam all express their deep obligation to the author. The Serious Call also affected others deeply. Samuel Johnson,[4] Gibbon, Lord Lyttelton and Bishop Home all spoke enthusiastically of its merits; and it is still the work by which its author is popularly known. It has high merits of style, being lucid and pointed to a degree.[2]

In a tract entitled The Absolute Unlawfulness of the Stage Entertainment (1726) Law was agitated by the corruptions of the stage to preach against all plays, and incurred some criticism the same year from John Dennis in The Stage Defended.[2]

His writing is anthologised by various denominations, including in the Classics of Western Spirituality series by the Catholic Paulist Press.

The devotional writer Andrew Murray was so impressed by Law's writings that he republished a number of his works, stating "I do not know where to find anywhere else the same clear and powerful statement of the truth which the Church needs at the present day."[5]

Mysticism[edit]

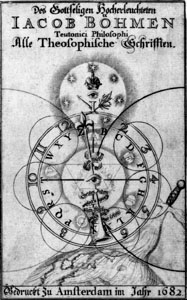

In his later years, Law became an admirer of the German Christian mystic Jakob Böhme. The journal of Law's friend John Byrom mentions that, probably around 1735 or 1736, the physician and Behmenist George Cheyne had drawn Law's attention to the book Fides et Ratio, written in 1708 by the French Protestant theologian Pierre Poiret. It was in this book that Law came across the name of the mystic Jakob Böhme.[6][7] From then on Law's writings such as A Demonstration of the Errors of a late Book (1737) and The Grounds and Reasons of Christian Regeneration (1739), began to contain a mystical note.[8] In 1740 appeared An Earnest and Serious Answer to Dr. Trapp and in 1742 An Appeal to All that Doubt. The Appeal was greatly admired by Law's friend George Cheyne, who wrote on 9 March 1742 to his good friend, the printer and novelist Samuel Richardson: "Have you seen Law's Appeal ... it is admirable and unanswerable". John Byrom wrote a poem based on An Earnest and Serious Answer, which was found among the manuscripts of Samuel Richardson after his death in 1761.[9]

Law's mystical tendencies caused the first breach in 1738 between Law and the practical-minded John Wesley after an exchange of four letters in which each explained his own position.[10] After eighteen years of silence Wesley attacked Law and his Behmenist philosophy once again in an open letter in 1756 in which Wesley wrote:

Law never responded to this open letter, though he had been deeply upset, as was testified by John Byrom.[12]

After seven years of silence Law further explored Böhme's ideas in The Spirit of Prayer (1749–1750), followed by The Way to Divine Knowledge (1752) and The Spirit of Love (1752–1754). He worked on a new translation of Böhme's works for which The Way to Divine Knowledge had been the preparation.[13] Samuel Richardson had been involved in the printing of some of Law's works, e.g. A Practical Treatise upon Christian Perfection (second edition of 1728), and The Way to Divine Knowledge (1752), since Law's publishers William and John Innys worked closely with Samuel Richardson.[14]

Law had taught himself the "High Dutch Language" to be able to read the original text of the "blessed Jacob". He owned a quarto edition of 1715, which had been carefully printed from the Johann Georg Gichtel edition of 1682, printed in Amsterdam where Gichtel (1638–1710) lived and worked.[15]

After the death of both Law and Richardson in 1761, Law's friends George Ward and Thomas Langcake published between 1764 and 1781 a four-volume version of the works of Jakob Böhme. It was paid for by Elizabeth Hutcheson. This version became known as the Law-edition of Böhme, even though Law had never found the time to contribute to this new edition.[16] As a result of this it was ultimately based on the original translations made by John Ellistone and John Sparrow between 1645 and 1662,[17] with only a few changes.[18] This edition was greatly admired by Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Blake. Law had found some illustrations made by the German early Böhme exegetist Dionysius Andreas Freher (1649–1728) which had been included in this edition. Upon seeing these symbolic drawings Blake said during a dinner party in 1825 "Michel Angelo could not have surpassed them".[19]

Law's Admiration for Isaac Newton and Jakob Böhme[edit]

Law greatly admired both Isaac Newton, whom he called "this great philosopher" and Jakob Böhme, "the illuminated instrument of God". In part I of The Spirit of Love (1752) Law wrote that in the three properties of desire one can see the "Ground and Reason" of the three great "laws of matter and motion lately discovered [by Sir Isaac Newton]". Law added that he "need[ed] no more to be told that the illustrious Sir Isaac [had] ploughed with Behmen's heifer" which had led to the discovery of these laws.[20]

Law added that in the mathematical system of Newton these three properties of desire, i.e. "attraction, equal resistance, and the orbicular motion of the planets as the effect of them", are treated as facts and appearances, whose ground appears not to be known. However, Law wrote, it is in "our Behmen, the illuminated Instrument of God" that:

====

Aldous Huxley quotes admiringly and at length from Law's writings on mysticism in his anthology The Perennial Philosophy, pointing out remarkable parallels between his ( Law's ) mystical insights and those of Mahayana Buddhism, Vedanta, Sufism, Taoism and other traditions encompassed by Leibniz's concept of the Philosophia Perennis.

Huxley wrote:

Aldous Huxley는 그의 선집 The Perennial Philosophy <영혼의 철학> 에서 신비주의에 관한 Law의 저술을 훌륭하고 길게 인용하여 그의 (Law) 신비로운 통찰력과 Mahayana 불교, Vedanta, Sufism, 도교 및 라이프니츠의 <영혼의 철학> 개념이 포괄하는 기타 전통 사이의 놀라운 유사점을 지적한다.

Huxley는 다음과 같이 썼다. 개인 영혼의 근거는 모든 존재의 신성한 근거와 유사하다고 인정합니다. 선과 악의 궁극적인 본성은 무엇이며, 삶의 진정한 목적은 무엇인가? 이러한 질문에 대한 답을 18세기 영국의 가장 놀라운 산물인 William Law가 제공한다. 그는영어 산문의 대가일 뿐만 아니라 당대의 가장 흥미로운 사상가이자 성공회 전체 역사에서 가장 사랑스러운 성인 중 한 명이다.

Veneration[edit]

Law is honoured on 10 April with a feast day on the Calendar of saints, the Calendar of saints (Episcopal Church in the United States of America) and other Anglican churches.

William is remembered in the Church of England with a Lesser Festival on 10 April.[23]

List of works[edit]

- Remarks upon a Late Book, Entituled, The Fable of the Bees (1724)

- "A Practical Treatise Upon Christian Perfection" (1726)

- A Serious Call to a Devout and Holy Life (1729)

- A Demonstration of the Gross and Fundamental Errors of a late Book called a Plain Account, etc., of the Lord's Supper (1737)

- The Grounds and Reasons of the Christian Regeneration (1739)

- An Earnest and Serious Answer to Dr Trapp's Sermon on being Righteous Overmuch (1740)

- Appeal to all that Doubt and Disbelieve the Truths of Revelation (1742)

- The Spirit of Prayer (1749, 1750)

- The Way to Divine Knowledge (1752)

- The Spirit of Love (1752-1754)

- A Short but Sufficient Confutation of Dr Warburton's Projected Defence (as he calls it) of Christianity in his Divine Legation of Moses (1757). Reply to The Divine Legation of Moses.

- A Collection of Letters on the Most Interesting and Important Subjects, and on Several Occasions (1760)

- Of Justification by Faith and Works, A Dialogue between a Methodist and a Churchman (1760)

- An Humble, Earnest and Affectionate Address to the Clergy (1761) renamed "The Power of the Spirit" by Andrew Murray in his 1896 reprint.

- You Will Receive Power

- The Way to Christ by Jakob Boehme, translated by William Law

Notes[edit]

- ^ "BBC - Religions - Christianity: William Wilberforce".

- ^ a b c d e f Chisholm 1911.

- ^ In A Serious Call to a Devout and Holy Life Law urges that every day should be viewed as a day of humility by learning to serve others. Foster, Richard J., Celebration Of Discipline, San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1988, p.131.

- ^ "I became a sort of lax talker against religion, for I did not think much against it; and this lasted until I went to Oxford, where it would not be suffered. When at Oxford, I took up Law's Serious Call, expecting to find it a dull book (as such books generally are), and perhaps to laugh at it. But I found Law quite an overmatch for me; and this was the first occasion of my thinking in earnest of religion after I became capable of rational inquiry.", Samuel Johnson, recounted in James Boswell's, Life of Johnson, ch. 1.

- ^ Murray, Andrew (1896). The Power of the Spirit. London: James Nisbet. pp. ix.

- ^ Joling-van der Sar 2003, pp. 112–113.

- ^ Joling-van der Sar 2006, pp. 442–465.

- ^ Joling-van der Sar 2003, pp. 120 ff.

- ^ Joling-van der Sar 2006, pp. 454–456.

- ^ Joling-van der Sar 2006, pp. 448–452.

- ^ J. Wesley, Works, Vol. IX, pp. 477-478.

- ^ Joling-van der Sar 2006, pp. 460–463.

- ^ Joling-van der Sar 2003, pp. 138 ff.

- ^ Joling-van der Sar 2003, pp. 118–120, 138.

- ^ This edition is the Theosophia Revelata. Das isst: Alle Göttliche Schriften des Gottseligen und hocherleuchteten Deutschen Theosophi Jacob Böhmens, 2 Vols., Johann Otto Glüssing, Hamburg, 1715.

- ^ This William Law edition is available online, see http://www.jacobboehmeonline.com/william_law.

- ^ Joling-van der Sar 2003, p. 144.

- ^ Joling-van der Sar 2003, pp. 138–141.

- ^ Joling-van der Sar 2003, p. 140.

- ^ Joling-van der Sar 2003, p. 133.

- ^ William Law, Works, 9 volumes, (reprint of the Moreton ed., Brockenhurst, Setley, 1892-93 which was a reprint of London edition of 1762), Wipf and Stock Publishers, Eugene, Oregon, U.S.A., 2001, Vol. VIII, pp. 19-20.

- ^ Huxley, Aldous 'The Perennial Philosophy', first edition pub. Chatto and Windus 1946.

- ^ "The Calendar". The Church of England. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

References[edit]

- Abby, Charles J., The English Church in the 18th Century, 1887.

- Foster, Richard J., Celebration Of Discipline, San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1988.

- Huxley, Aldous, The Perennial Philosophy, 1945.

- Joling-van der Sar, Gerda J. (2006). "The controversy between William Law and John Wesley". English Studies. Informa UK Limited. 87 (4): 442–465. doi:10.1080/00138380600757810. ISSN 0013-838X.

- Joling-van der Sar, Gerda J. (2003). The spiritual side of Samuel Richardson : mysticism, Behmenism and millenarianism in an eighteenth-century English novelist (Thesis). University of Leiden. ISBN 90-90-17087-1. OCLC 783182681. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- Lecky, W.E.H, History of England in the 18th Century, 1878–90.

- Overton, John Henry, William Law, Nonjuror and Mystic, 1881.

- Stephen, Leslie, English Thought in the 18th century.

- Stephen, Leslie (1892). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 32. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Tighe, Richard, A Short Account of the Life and Writings of the Late Rev. William Law, 1813.

- Walker, A.Keith. William Law: His Life and Work SPCK, 1973.

- Walton, Christopher, Notes and Materials for a Complete Biography of W Law, 1848.

Attribution:

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Law, William". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links[edit]

Quotations related to William Law at Wikiquote

Quotations related to William Law at Wikiquote- The Life and Works of William Law - all 17 known works.

- Works by or about William Law at Internet Archive

- Works by William Law at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by William Law at Open Library

- William Law Page with the William Law Edition of Jakob Böhme

- The Mystical Writings of William Law webpage

- [1]

Law, William

Views 3,155,337Updated May 29 2018

https://www.encyclopedia.com/people/philosophy-and-religion/protestant-christianity-biographies/william-law

LAW, WILLIAM

LAW, WILLIAM (1686–1761), was an English devotional writer. Born at King's Cliffe, Northamptonshire, William Law came from a family "of high respectability and of good means." He entered Emmanuel College, Cambridge, in 1705 to prepare for the Anglican ministry; he achieved the B.A. in 1708 and the M.A. in 1712, the same year in which he received a fellowship and ordination. He read widely from the classics, the church fathers, and the early mystics and devotional writers, and he studied science and philosophy as well. Law's refusal to take oaths of allegiance and abjuration upon the accession of George I deprived him of his fellowship and his right to serve as minister in the Church of England. He remained loyal to the state church, however, throughout his life. After an extended period as tutor to Edward Gibbon, father of the historian, Law took up permanent residence at his birthplace, King's Cliffe, where he served as spiritual adviser to many, engaged in acts of charity to the deprived of the community, and wrote the nine volumes that make up his major works.

Law's early writings include Remarks upon the Fable of the Bees (1723), a refutation of Bernard Mandeville's work; The Unlawfulness of Stage Entertainment (1726); The Case of Reason or Natural Religion (1731); and two better-known works, Treatise upon Christian Perfection (1726) and A Serious Call to a Devout and Holy Life (1729). These latter contribute significantly to a tradition of devotional prose literature that includes such writers as Augustine, Richard Baxter, Jeremy Taylor, John Donne, and Lancelot Andrewes. Law's devotional writing has as its controlling purpose the aiding of persons in their quest of the "godly life," and it reveals several distinguishing themes: preoccupation with the scriptures and Christ as the bases and models for perfection; self-denial as a necessary antidote to vainglory and passion; prayer and meditation; and ways and means for implementing Christian doctrine in practical affairs.

Among Law's later work were responses to various religious writers: The Grounds and Reason for Christian Regeneration (1739), An Appeal to All Who Doubt the Truths of the Gospel (1740), An Answer to Dr. Trapp's Discourse (1740), and A Refutation of Dr. Warburton's Projected Defense of Christianity (1757). More influential, however, were the mystical writings The Spirit of Prayer (1749), The Spirit of Love (1752), and The Way to Divine Knowledge (1752). These three works reveal the influence of Jakob Boehme, who professed visionary encounters with God. Many Christian critics have objected to the oversubjectivism and implicit universalism in Law's later writings, branding them as "mystical," a term often held as opprobrious by traditional religious thinkers. However, if one considers an intuitive approach to reality, awareness of unity in diversity, and a passion for a spiritual reality that underlies and unifies all things to be typical of mysticism, one realizes that this desire for union with God lies at the root of all religious devotion. In this light, Law's "mystical" works reflect his earlier theological beliefs and have a close kinship with his Christian Perfection and A Serious Call.

Many readers have paid tribute to Law's simple, clear, and vivid prose style, and scholars have pointed to his pronounced religious influence on such minds as Samuel Johnson, John Wesley, John Henry Newman, Charles Williams, and C. S. Lewis. His intellectual power, incisiveness, and piety wielded a marked influence both within and without organized church ranks. Law's major achievement lay in his significant contribution to the English tradition of devotional prose literature.

Bibliography

Primary Source

Law, William. The Works of the Reverend William Law, M.A. (1762). Reprint, 9 vols. in 3, London, 1892–1893.

Secondary Sources

Baker, Eric. A Herald of the Evangelical Revival. London, 1948. Examines basic views of Law and Jakob Boehme and shows how Law kindled in Wesley a passion for an unimpaired "ethical ideal."

Hopkinson, Arthur. About William Law: A Running Commentary on His Works. London, 1948. Recognizes works with different subjects: religious controversy, morality, mysticism, and theology. Sketchy but informative.

Overton, John H. William Law: Nonjuror and Mystic. London, 1881. Still the best single source for Law's life and thought.

Rudolph, Erwin P. William Law. Boston, 1980. Examines the range of Law's thought and contribution to devotional prose literature.

Walker, Arthur K. William Law: His Life and Thought. London, 1973. Examines Law's intellectual biography, focusing on the people whom Law knew and the writings with which he was familiar. Sometimes digressive and biased but generally useful.

Erwin P. Rudolph (1987)

Encyclopedia of Religion Rudolph, Erwin

Law, William (1686-1761)

Views 3,895,598Updated May 23 2018

Law, William (1686-1761)

English mystic and theologian. William Law was born in 1686, at King's Cliffe, Northamptonshire, England. His father, a grocer, managed to send William to Cambridge University in 1705. Entering Emmanuel College, he became a fellow in 1712, but on the accession of George I in 1714, felt himself unable to subscribe to the oath of allegiance. As a result, Law forfeited his fellowship.

In 1727 he went to Putney to tutor the father of Edward Gibbon, the historian of the Roman Empire. He held this post for 10 years, winning universal esteem for his piety and theological erudition.

When his employer died in 1737, Law retired to his native village of King's Cliffe and was chiefly supported by some of his devotees, notably Hester Gibbon, sister of his guardian pupil, and the widow Mrs. Hutcheson. The two women had a united income of fully 3,000 pounds a year, so Law must have been comfortable, and wealth and luxury did not corrupt him. It is recorded that he rose every morning at five and spent several hours before breakfast in prayer and meditations.

Early in his career, Law began publishing theses on mysticism and on religion in general. After he retired, he acquired fresh inspiration from reading the works of Jakob Boehme, of which he was an enthusiastic admirer, and produced year after year a considerable mass of writing until his death April 9, 1761.

Law's works comprise some 20 volumes. In 1717 he published an examination of the recent tenets of the bishop of Bangor, which were followed soon after by a number of analogous writings. In 1726 his attack on the theater was published as The Absolute Unlawfulness of the Stage Entertainment Fully Demonstrated. In the same year he issued A Practical Treatise upon Christian Perfection, followed shortly thereafter by A Serious Call to a Devout and Holy Life, Adapted to the State and Condition of All Orders of Christians (1728), considered his best-known work.

Other well-regarded works include: The Grounds and Reason of Christian Regeneration (1739), The Spirit of Prayer (1749), The Way to Divine Knowledge (1752), The Spirit of Love (1752), and Of Justification by Faith and Works (1760).

Most of Law's books, especially A Serious Call, have been reprinted again and again, and a collected edition of Law's works appeared in 1762, a year after his death. In 1893 an anthology was brought out by Dr. Alexander Whyte. In his preface Whyte spoke of Law's "golden books," declaring that "in sheer intellectual strength Law is fully abreast of the very foremost of his illustrious contemporaries, while in that fertilising touch which is the true test of genius, Law stands simply alone."

Sources:

Law, William. The Absolute Unlawfulness of the Stage Entertainment Fully Demonstrated. Reprint, New York: Garland Publishing, 1973.

——. The Grounds and Reason of Christian Regeneration. Philadelphia: Andrew Bradford, 1741.

——. A Practical Treatise upon Christian Perfection. Newcastle upon Tyne: J. Gooding, 1743.

——. A Serious Call to a Devout and Holy Life, Adapted to the State and Condition of All Orders of Christians. London: W. Innys, 1732.

——. The Spirit of Love. London: W. Innys and J. Richardson, 1752.

——. The Spirit of Prayer. London: W. Innys, 1750.

——. The Works. Brockenhurst: G. Moreton, 1892-93. Rudolph, Erwin Paul. William Law. Boston: Twayne, 1980.

Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology

William Law

Views 3,789,199Updated May 29 2018

William Law

The English devotional writer, controversialist, and mystic William Law (1686-1761) wrote works on practical piety that are considered among the classics of English theology.

William Law was born in King's Cliffe, North-amptonshire, the son of a grocer and one of 11 children. In 1705 he was sent to Emmanuel College, Cambridge. He earned a bachelor of arts degree in 1708, was ordained in 1711, and became a fellow of Emmanuel in 1712. In 1713 Law was suspended from his fellowship for delivering a speech in which it appeared he supported the Stuart pretender to the throne rather than the future George I of Hanover. In 1714 at the accession of George I, he refused to take the oath of allegiance, becoming, in the nomenclature of the day, a nonjuror. As a result, for the rest of his life he occupied no benefice in the Church of England and appears to have officiated at no religious services.

In 1727 Law became tutor at Putney to the father of the eminent historian Edward Gibbon and was considered a respected member of the family circle. In 1740 Law returned to King's Cliffe, soon to be joined by Hester Gibbon, the aunt of the historian, and another lady of quality, Mrs. Hutchenson. Through their assistance Law was able to devote himself to study and charitable activities until his death. He set up schools, provided food for the poor, and became a spiritual adviser renowned as a man of singular compassion and simplicity.

Law's chief fame, however, rests on his writings. In an age when much theological thought was deeply affected by the rationalism of John Locke and Isaac Newton, Law became a vocal spokesman for the need to return to a religion of piety and feeling. As a result, Law entered into a number of controversies with leading thinkers of his day. In 1717 he attacked Bishop Hoadly's contention that the visible church and priesthood had no claim to divine authority. In 1723 a critique of Bernard Mandeville's Fable of the Bees appeared, in which Law defended morality against Mandeville's argument that man was motivated completely by self-interest. In 1731 Law published a forceful rejoinder to the deist Mathew Tindal, in which Law denied the total efficacy of reason.

It is, however, Law's A Serious Call to a Devout and Holy Life (1728) which is regarded as his most enduring work. Emphasizing the need to be a Christian in spirit and deed as well as in name, the tract is an uncompromising demand for continual and heartfelt Christian dedication. Beautifully written, this work had a tremendous impact in its day, carrying its message to such diverse 18th-century figures as Dr. Samuel Johnson, John Wesley, and Edward Gibbon.

Through his concern for the religion of the heart and through the reading of mystical literature, Law in his later years developed a unique and personal mysticism. Dwelling on the "inner spirit" of Christ within man, his thought became less orthodox and his conception of religion less formal, though he never left the Church of England.

Further Reading

Law receives comprehensive treatment in J. H. Overton, William Law, Non Juror and Mystic (1881). There is a skeptical but sympathetic account of him in Leslie Stephen, History of English Thought in the 18th Century (2 vols., 1876). See also W. R. Inge, Studies of English Mystics (1906); Stephen Hobhouse, William Law and Eighteenth Century Quakerism (1927); and J. B. Green, John Wesley and William Law (1945).

0 seconds of 15 secondsVolume 0%

00:22

01:04

Additional Sources

Rudolph, Erwin Paul, William Law, Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1980. □

Encyclopedia of World Biography

Law, William

Views 3,311,371Updated May 23 2018

LAW, WILLIAM

High Anglican ecclesiastic and spiritual author; b. Kings Cliffe, Northamptonshire, 1686; d. there, April 9,1761. He was the son of a grocer. He entered Emmanuel College, Cambridge, in 1705. After ordination, he was elected a fellow of his college in 1711 and taught at Cambridge until the accession of George I in 1714, when he was suspended from his degree and deprived of his fellowship for his Jacobite sympathies. From 1727 to 1737, Law resided with the family of Edward Gibbon, grandfather of the historian, as tutor and as spiritual guide for the family and their friends, among whom were Archibald Hutcheson and John and Charles wesley. After 1743 Hutcheson's widow and Gibbon's sister joined Law at Kings Cliffe in a life of simplicity, devotion, and prayer inspired by ideals set forth in Law's Serious Call to a Devout and Holy Life (1728). They maintained two small schools and used their considerable incomes for charity. Law was the ablest High Church writer of his day: direct, simple, and logical in his exposition of Christian ideals. His influence was limited, however, because he wrote in opposition to the prevailing tendencies of his time. In the Bangorian Controversy of 1716–17, he opposed the party supported by the crown. He wrote forcefully against deism at a time when the deist and rationalist approach to religious studies, popularized by John locke, was in its heyday. In 1726 he wrote a work condemning the contemporary theater.

Law had always been interested in such late medieval mystics as thomas À kempis, tauler, and ruysbroeck, whose influence appears in the Serious Call. He advocated a full Christian life, with attention to meditation, ascetical practices, and moral virtues, especially those of daily life—everything being directed to the glorification of God. The Serious Call was the most influential spiritual work, apart from Pilgrim's Progress, after the English Reformation. In 1737 Law fell under the influence of the Moravian mystic Boenler and the German Jacob bÖhme. His later works, The Spirit of Prayer (1749–50) and The Spirit of Love (1752–54), which emphasize the indwelling of Christ in the soul, led the Wesleys to break with him, although they continued to admire him. Law's doctrine tended toward the Quaker conception of the Inner Light.

Bibliography: Works, 9 v. (London 1892–93). s. h. gem, The Mysticism of William Law (London 1914). l. stephen, Dictionary of National Biography from the Earliest Times to 1900 (London 1885–1900) 11:677–681. j. b. green, John Wesley and William Law (London 1945). e. w. baker, A Herald of the Evangelical Revival (London 1948). m. schmidt, John Wesley, tr. n. p. goldhawk (London 1962) 1. m. schmidt, Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart 4:245. f. l. cross, The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (London 1957) 791.

[b. norling]

New Catholic Encyclopedia NORLING, B.

Law, William

Views 3,949,499Updated May 14 2018

Law, William (1686–1761). Law, one of the most influential religious writers of his age, came from a modest family at King's Cliffe, near Stamford, and was elected to a fellowship at Emmanuel College, Cambridge. But in 1714 he refused to take the oaths of loyalty to George I and was deprived of his fellowship. He then became tutor to Gibbon's father. His most famous work, A Serious Call to a Devout and Holy Life (1728), preached a quiet and meditative Christianity, restrained, humble, and charitable. Johnson spoke of the great effect it had upon him as a student and Wesley and Whitefield were also much influenced. In 1732 he published The Case of Reason, arguing faith against deistical scepticism. From 1740 he established at King's Cliffe a devout household, including the widow of Archibald Hutcheson, MP, and Gibbon's aunt Hester. Most of their income went on schools, almshouses, and the poor, and their charity attracted so many beggars that there was bad feeling in the village. When Miss Gibbon died in 1790 at the age of 84, her nephew wrote, disrespectfully: ‘aunt Hester is gone to sing Hallelujahs, a glory she did not seem very impatient to possess. I received the news of this dire event with much philosophic composure.’

J. A. Cannon