Future Perfect: Tolstoy and the Structures of Agrarian-Buddhist Utopianism in Taishō Japan

Comparative Humanities Program, Bucknell University, Lewisburg, PA 17837, USA

Religions 2018, 9(5), 161; https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9050161

Received: 22 April 2018 / Revised: 11 May 2018 / Accepted: 13 May 2018 / Published: 16 May 2018

(This article belongs to the Special Issue Engaging Violence: Case Studies from the Japanese Religious Traditions)

This study focuses on the role played by the work of Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910) in shaping socialism and agrarian-Buddhist utopianism in Japan. As Japanese translations of Tolstoy’s fiction and philosophy, and accounts of his life became more available at the end of the 19th century, his ideas on the individual, religion, society, and politics had a tremendous impact on the generation coming of age in the 1900s and his popularity grew among young intellectuals. One important legacy of Tolstoy in Japan is his particular concern with the peasantry and agricultural reform. Among those inspired by Tolstoy and the narodniki lifestyle, three individuals, Tokutomi Roka, Eto Tekirei, and Mushakōji Saneatsu illustrate how prominent writers and thinkers adopted the master’s lifestyle and attempted to put his ideas into practice. In the spirit of the New Buddhists of late Meiji, they envisioned a comprehensive lifestyle structure. As Eto Tekirei moved to the village of Takaido with the assistance of Tokutomi Roka, he called his new home Hyakushō Aidōjō (literally, Farmers Love Training Ground). He and his family endeavored to follow a Tolstoyan life, which included labor, philosophy, art, religion, society, and politics, a grand project that he saw as a “non-religious religion.” As such, Tekirei’s utopian vision might be conceived as an experiment in “alter-modernity.”

1. Introduction

The primary foreign influence on early Japanese socialism—including the two main forms of religious socialism, Christian and Buddhist—was the work of Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910), Russian essayist, pacifist, Christian socialist and, of course, author of some of the most significant works of 19th century world literature.1 Although portions of War and Peace had been published in Japan as early as 1886, it was in 1889 and 1890—coinciding with the proclamation of both the Imperial Constitution and the Rescript on Education—that Japanese translations of Tolstoy’s fiction and philosophy, and accounts of his life, began to appear in journals such as Kokumin no tomo, Shinri, Tetsugaku zasshi, and Rikugō zasshi. The year 1890 also saw the publication in Nihon hyōron of a report on Tolstoyan humanism by the Christian theologian and critic Uemura Masahisa (1857–1925). Over the next decade, many of Tolstoy’s shorter works became available in Japan, including The Cossacks (1893) and Kreutzer Sonata (1894), both of which had a significant influence. (See Nobori 1981, pp. 34–37; Shifman 1966, pp. 59–64).

No doubt part of the attraction of Tolstoy as a writer of fiction was his blend of naturalism and humanism, two significant literary trends that were just emerging in late Meiji and early Taishō Japan. (See Sibley 1968, p. 162, n.15). Tolstoy’s ideas on the individual, religion, society, and politics were of immense influence on the “young men of Meiji,” the generation coming of age in the last decade of the Meiji period.2 As the historian Steven Marks puts it: “His writings encapsulated in highly readable form the Russian philosophical stress on the illusory nature of Western progress, and the virtues of either backwardness or delaying the onset of Western modernization, ideas that reverberated throughout the non-Western world.” (Marks 2003, p. 123). This resonance was particularly strong in Japan, a nation struggling with many of the same issues regarding modernization, industrialization, and its relationship to the West as Tolstoy’s Russia.

Tolstoy held a deep respect and appreciation for Asian culture, dabbled in Buddhism, and denounced Western imperialism and colonialism, urging non-Western peoples to resist (nonviolently) becoming slaves or puppets to the West and its ideals.3 His outspoken opposition to the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905) won him many adherents among students, progressive intellectuals, and the Japanese left (including many Christians and Buddhists), while rendering him a pernicious influence in the eyes of the late-Meiji and early-Taishō administrations. Prominent leftists such as Abe Iso’o (1865–1949), Kōtoku Shūsui (1871–1911), Kitamura Tokoku (1868–1894), and Ōsugi Sakae (1885–1923) acknowledged Tolstoy as an influence and inspiration. As a result, combined with a more general fear of the growth of radical thought among the young, in the decade between 1905 and 1915 Tolstoy was among those authors whose works were targeted as being detrimental to public morals. To the chagrin of government officials and associated ideologues, however, the Russian writer’s influence continued to grow throughout the Taishō era, so much so that a new term was coined—Torusutoishugi—to describe the popular phenomenon of adopting a “Tolstoyan lifestyle.”

One important legacy of Tolstoy in Japan is his particular concern with the peasantry and agricultural reform. The so-called “rediscovery” of the Japanese countryside in late Meiji is sometimes attributed to his influence. Many if not most agrarian reform movements of the early century were directly inspired by Tolstoy’s work, often mixed with the writings of the Russian anarchist Peter Kropotkin (1842–1921). That is not to say that there were no indigenous roots to this turn to the countryside: Zen Buddhism (influenced by the primitivist stream within Chinese Daoism) has long held to the ideal of a simple, rustic existence, while the practices of folk Shinto are rooted in visits to rural shrines. Yet the contrast one finds in Tolstoy—filtered through Rousseau and the European romantics—between the “countryside” as the locus for true humanity and the “city” as the emblem of strife, unease, and suffering, was new to Japan, though it grafted readily onto 19th century nativist appeals to agricultural productivity and peasant life as a solution to Japan’s problems. (See Harootunian 1988, pp. 49–50, 251; Tamamoi 1998; Konishi 2013, p. 23).

Tolstoy and his followers have frequently been labeled “antimodern,” based on a simplistic conflation of modernity and urban culture. Indeed, while Japanese leftists (and some rightists) were attracted to Tolstoy’s agrarian romanticism as a response to Western (bourgeois, urban) civilization, his work contains elements that are distinctly “modern(ist),” including his rationalist interpretation of religion and proto-existentialist focus on the individual. And despite official disapproval, by the early Taishō there was a feeling that Japan’s adoption of Tolstoy (along with the more obviously modernist Henrik Ibsen) was a sure sign that the country had emerged into the “modern world” and the early Meiji impulse had paid off (Marks 2003, p. 125).

2. The Narodniki: Farmer’s Institutes and New Villages

In short, the impact of Tolstoy among young intellectuals in late Meiji and Taishō Japan can hardly be overstated. Yet Tolstoy was not simply a religious reformer or social critic; he was also recognized as one the great writers of the late 19th century—and as such, his influence extended to the world of letters. Among the earliest Japanese writers influenced by Tolstoy, several of the most prominent were Tokutomi Roka (1868–1927), Eto Tekirei (1880–1944), and Mushakōji Saneatsu (1885–1976). All three men identified strongly with Tolstoy, not only as writers and thinkers but also in terms of adopting the master’s lifestyle and attempting to put his ideas into practice. In particular, they were attracted to what Akamatsu Katsumaro (1894–1955) called “the practical effectiveness of Tolstoy’s doctrines of love, labor, nonresistance, and reverence for the agrarian way of life.” (Akamatsu 1981, p. 98).

On the way back from a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, Roka—younger brother of the well-known historian and critic Tokutomi Sohō (1863–1957)—visited Tolstoy’s villa in Yasnaya Polyana in 1906, and soon began to inject his literary works with Tolstoyan qualities of introspection and a resistance to authoritarianism.4 In 1908, as leftist activism grew in the wake of the Russo-Japanese War, he gave a controversial address to the Debating Society of the First Higher School of Tokyo entitled “The Sadness of Victory,” in which he evoked the emptiness felt by even the greatest generals upon their so-called victories in battle, concluding, in words that evoke the Buddhist conversion of the legendary King Ashoka (304–232 BCE) after the battle of Kalinga: “Of what value is man’s victory? The people search after ‘success’ or ‘distinction,’ offering their very lives in payment. But what is success, what is distinction? These are nothing more than pretty reflections shining forth from the dream of man’s aspirations” (cited in Akamatsu 1981, p. 99). Apparently, this speech hit a chord with a number of students in the audience, some of who promptly quit school to return to their native village as narodniki.5 Roka himself would spend his final two decades ensconced with his wife in a Musashino forest retreat called Kōshun-en, living the life of a “natural man” (shizenjin).

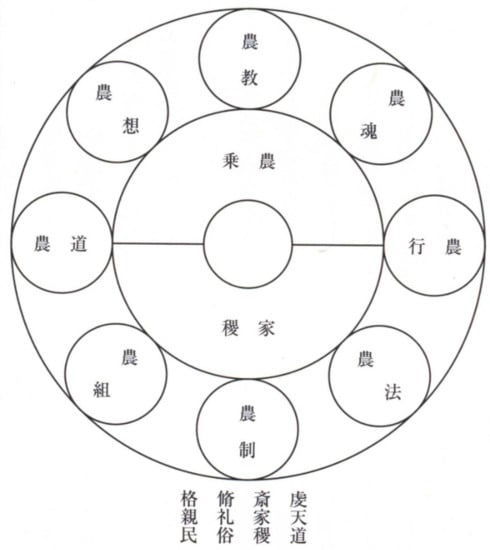

Eto Tekirei was another budding intellectual and writer who got caught up in the Tolstoyan currents of the early 20th century. Around 1906, inspired by Tolstoy and the narodniki lifestyle, he abandoned his studies at Tokyo Imperial University and took up the life of a farmer. Yet even this was not enough, so in 1910, with the assistance of Tokutomi Roka, Tekirei took up residence in the village of Takaido in the Musashino area just outside of Tokyo.6 Giving his new home the grandiose title Hyakushō Aidōjō (literally, Farmers Love Training Ground), he and his family attempted to follow a Tolstoyan life to the fullest, while incorporating—like so many other Japanese narodniki—Buddhist and Christian elements into his thought, including the work of Christian socialist Uchimura Kanzō (1861–1930). An eclectic thinker, Tekirei also borrowed heavily from the work of Russian anarchist Kropotkin, whose Fields, Factories, and Workshops “really taught [him] how to live a life of labor,” (Akamatsu 1981, p. 100; see also Eto 1925; Nishimura 1992, p. 170; Nakao 1996, p. 174). He was among the first Japanese scholars to “rediscover” the work of Andō Shōeki (1703–1762), the Edo-period agrarian thinker and proto-communist visionary.7 In 1922, Tekirei published his Aru hyakushō no ie (The household of a certain farmer), which, together with Tsuchi to kokoro o tagayashi tsutsu (Tilling the soil and the heart, 1924), serves as both memoir and justification for his agrarian socio-religious vision. Eto’s agrarian-Buddhist vision is encapsulated in his “wheel of household grain farming” (Figure 1).

Citing Maruyama Masao’s remarks on the tendency towards ideological polarization during this period, Nishimura Shun’ichi argues that this tendency extended to late Meiji and Taishō denenshugi (agrarianism) as well, such that there emerged a “right wing” faction of thinkers dedicated to nōhonshugi (literally, agriculture-essence-ism) and a “left wing” or progressive faction espousing nōminjichishugi (farmer-autonomy-ism) (Nishimura 1992, p. 88; also see Nakao 1996). Nishimura places Tekirei in the latter group, along with Ishikawa Sanshirō (1876–1956), Shimonaka Yasaburō (1878–1961), and Ōnishi Goichi (1898–1992), as opposed to “rightists” such as Gondō Seikyō (1868–1937), Tachibana Kōzaburō (1893–1974), Yamazaki Nobuyoshi (1873–1954), and Katō Kanji (1884–1967).8 Given Tekirei’s primary inspirations—Tolstoy, Kropotkin, and Shōeki—his radically “horizontal” focus and concomitant rejection of hierarchy, this is not a difficult case to make. And yet it is worth asking: just how reliant was Tekirei on Buddhist ideas and principles for his progressive, naturalist vision?

After a few years of life as a farmer, Tekirei began to have serious doubts about Tolstoy’s idealized views of peasant life, and resolved to establish a new system for living with nature, which he called kashoku nōjō (Wheel of household grain farming). In fact, the first half of this four-character set, kashoku, is borrowed directly—and effectively set in ironic contrast to—the traditional term shashoku, used to refer to the state as a tutelary deity of grain. Here, in Tekirei’s reformulation, it is the household (ie) that becomes the locus of livelihood, rather than the state. In addition, the final character jō is clearly borrowed from Buddhist tradition, where it refers to a particular “vehicle” or branch of the Dharma, one that leads effectively to nirvana—as in the Great Vehicle (Mahayana; Daijō). Tekirei goes on to divide this general concept into eight categories: (1) agrarian methods (nōhō); (2) agrarian organization (nōsei), (3) agrarian association (nōso), (4) agrarian “path,” including social and economic standpoints (nōdō), (5) agrarian thought, including philosophy and art (nōsō), (6) agrarian doctrine, including culture (nōkyō), (7) agrarian spirit, including spirituality and religion (nōkon), (8) agrarian practice (nōgyō) (Nishimura 1992, p. 171).

Clearly, in the spirit of the New Buddhists of late Meiji, Tekirei is aiming for a comprehensive lifestyle structure—one that stretches (or better, softens) the boundaries between labor, philosophy, art, religion, society, and politics. Indeed, due to its application to all facets of ordinary life, he would go on to call his vision a “non-religious religion” (mushūkyō no shūkyō).9 Moreover, Tekirei seems to have followed Shōeki’s understanding of the intrinsic relation of nature, labor, and knowledge. While nature cannot be known in its entirety, it can (and should) be “practiced” through agricultural labor. Labor also brings knowledge—including knowledge of the limits of practice itself, and out of this emerges “a natural community [resting]…on overflowing surplus energies and interactive natural practices.”10

We find a remarkably similar vision in the following declaration of principles in the journal Aozora (Blue sky), founded in 1925 by Ōnishi Goichi and Ikeda Taneo (1897–1974):

- 1

- As children born with the great earth as our mother and the vast sky as our father, we believe that we must find the foundation for our daily lives in the spirit of the pure farmer, and that moreover this is the very root of human existence.

- 2

- We repudiate the urban-based civilization, which continues to oppress and trample down the people both spiritually and economically, and pledge instead to establish an agriculturally based civilization that conforms to the land.

- 3

- This creed is not meant to give birth to yet another fixed doctrine; rather, we simply look to reconnect with our innate disposition to till the great earth and lead the natural life of the farmer.11

While the soil-peasant fixation is stronger here than with the mainly urban New Buddhists of late Meiji, there are palpable affinities to some earlier Buddhist progressives with regard to the emphasis on reaching beyond “civilization” toward some deeper foundation for human existence and the desire to be “nonpartisan” and “post-ideological”—without thereby losing the capacity to engage in forthright criticism. And while we might find parallels with right-leaning evocations of a “return to the soil” in the work of Katō Kanji and other advocates of nōhonshugi, here—as with the New Buddhist Fellowship (Shin Bukkyō Dōshikai)—there is a noticeable lack of mention of the state or kokutai (national polity). In short, at issue is the individual’s relations with (a) nature, (b) themselves, and (c) their society or community. In similar fashion, Eto Tekirei was fiercely resistant to the notion—promoted by, for instance, nōhonshugi activist Yamazaki Nobuyoshi (1873–1954), that “going back to the land” must become codified as a matter of “national policy” (see Nishimura 1992, p. 171).

Tekirei also borrowed heavily from the work of Dōgen (1200–1253), taking particular note of the Soto Zen master’s emphasis on the bodily basis of awakening. As Wada Kōsaku explains, this became the basis of Tekirei’s idea of “practice” (gyō) (Wada 2012, pp. 12–14). Elsewhere he writes that while he never practiced shikantaza in a meditation hall, he did so in the “heaven and earth meditation hall” (tenchi zendō)—while engaged in the “practice” of farming (see Saitō et al. 2001, p. 232). And with regard to the matter of work and nature, he relied upon the following passage from the Devadatta chapter of the Lotus Sutra, describing the Buddha’s reminiscences of his past life as a king who has renounced his throne to follow a teacher of the “wonderful law”: “Picking fruit, drawing water, gathering firewood, and preparing food, even offering my own body as a couch for him, feeling no weariness in body or mind. I served him for a thousand years, for the sake of the Dharma, diligently waiting upon him so he lacked nothing.”12

While the trope of the “suffering” or “self-sacrificial” servant was also put to good use by kokutai ideologues, Tekirei resisted the self-denying emphasis of nōhonshugi in favor of what can only be called an “individualist” quest for existential truth. In this respect, his critique of Marx is worth noting, in that—again like his New Buddhist predecessors—he accepts the basic premises of the Marxist (as well as the Darwinian) critique of traditional “idealist” philosophies and religions while resisting the harder-edged implications of a kind of materialism (and determinism) that treats human beings simply as “matter” or as “animals” (see Wada 2012, pp. 59–64). In many respects, Tekirei’s eclectic philosophy is rooted in principles similar to the seishinshugi of Kiyozawa Manshi (1863–1903), so it comes as no surprise to learn that in early 1902 the young Tekirei visited the Kōkōdō to hear Kiyozawa lecture on Shinran (1173–1263) and was favorably impressed by the older man. Two decades later he would write that it was due to Kiyozawa (in particular his reading of Shinran), that Tekirei first truly discovered the “self” (shi).13 He would later have contact with two of Kiyozawa’s chief students: Akegarasu Haya (1877–1954) and Chikazumi Jōkan (1870–1941).

Finally, we turn to the third and most influential of our Tolstoyan narodniki: Mushakōji Saneatsu. As the son of a viscount descended from the highest ranks of nobility (kuge), Mushakōji received an elite—and cosmopolitan—education at Gakushūin (Peers’ School) in Tokyo, coming into early contact with the work of Tolstoy as well as the Bible.14 From his school years, he would later recount, his “utmost desire was to become a champion of humanitarianism, a great man of letters and a great thinker … a just man, and to lead a life so holy that he might pass for a paragon of virtue in the eyes of God… ”15 Though initially enrolled in the Department of Philosophy at Tokyo Imperial University, his interests soon turned toward literature, and, like Eto Tekirei, he dropped out prior to graduation. By this time, Mushakōji had come into contact with a number of talented and like-minded young writers, with whom he would found the Shirakaba-ha (White Birch School) in 1910 (see Mortimer 2000, pp. ix–x).

Along with the other members of the White Birch School, through the pages of their publication Shirakaba, Mushakōji promoted a form of idealist humanism that went against the popular literary trend of naturalism, which tended toward a fatalistic and pessimistic view of human life caught up in forces beyond its control. In contrast, Mushakōji and the other writers of the White Birch School embraced an optimistic view of human potential, in which the individual was largely in control of his own destiny via the power of the will.16 Yet Mushakōji—like Tolstoy and the narodniki discussed above—was not content to be simply a writer; he longed to put his ideas into practice, an opportunity that presented itself in 1918, with the founding of the utopian community Atarashikimura (New Village) at Kijōmura, an isolated spot in the mountains of Miyazaki prefecture, Kyushu. Despite the inevitable troubles (both financial and personal), Atarashikimura seems to have flourished for its first decade—reaching a peak around 1929. The site was condemned in 1938 to allow for the construction of an electrical power plant. A second New Village was then established in Saitama prefecture, and several branches arose elsewhere, a few of which continue to this day.

To some extent, Musahakōji struggled with the same problem as the New Buddhists and the other narodniki: how to reconcile self-discovery and individual freedom with social responsibilities and political obligations (see, e.g., Epp 1996, p. 17). In the immediate aftermath of the High Treason Incident (Taigyaku jiken) of 1910–11, and with more focus on the “self” in Taishō intellectual and literary circles, the problem had become even more acute—and significantly more politically sensitive. Given this context, it is hardly surprising that, taken as a whole, what we might call Taishō “humanism”—whether fortuitously or as a form of self-censorship in the wake of the High Treason Incident—was not overly concerned with social problems. Indeed, it has become something of a scholarly consensus that Taishō literature, in particular, represents an “inward turning” away from the social consciousness expressed in the works of late Meiji “naturalism (see, e.g., Kohl 1990, p. 9). “[I]f one characteristic of this early phase of the Taishō discovery of the self lies in confession, another seems to be a blocking out of social concern, at least in an analytic sense” (Rimer 1990, p. 35; Mortimer 2000, p. 146).

In this regard, the Shirakaba writers—and Mushakōji in particular—appear to have a mixed record. Maya Mortimer argues that, despite their “reverence for Tolstoy”—which would seem to gain them a certain progressive credibility—the “Shirakaba concern for the visual arts… and the emphasis, through Mushanokōji, on self-fulfillment, seemed designed to reassure the authorities that the group had effectively withdrawn from the political arena,” and that even the founding of Atarashikimura in 1918 was not a “return to politics” but rather a form of escapism: “based on pastoral nostalgia and exploiting the ethical and quietist aspects of Tolstoyanism as a defense against those who reproached the group’s lack of political involvement.”17 On the other hand, Stephen Kohl contrasts the work of Mushakōji and fellow Shirakaba member Arishima Takeo (1878–1923) with that of Abe Jirō (1883–1959), author of the hugely popular Santarō no nikki (Diary of Santarō, 1914): “When Mushanokōji spoke of the self, he was calling for the improvement of both the self and society at large. Abe’s concern for the self is so inward-looking that his vision rarely goes beyond the identification and edification of the individual self” (Kohl 1990, p. 9). If we assume that Kohl is correct to emphasize a “social” aspect to Mushakōji’s focus on the self—distinct from many Taishō “humanists”—then what, if anything, precludes this from being “political”?

The founding of Atarashikimura in the summer and fall of 1918 was the culmination of Mushakōji’s long-standing utopian dream—and represents the concrete embodiment of his deepest personal values and ideals. The commune was born in the midst of two events of both global and local resonance: the Russian Revolution of October 1917 and the end of the Great War the following autumn. A surge in social unrest within the country—exemplified by the Rice Riots in Tokyo, Osaka, and Kobe—compounded the fears of the Taishō administration, showing that the Meiji experiments with nation building and the attempt to create a harmonious social order had not yet achieved resolution (see Smith 1970, p. 91; Ohnuki-Tierney 1994, pp. 38–39). Very much in the Tolstoyan anti-authoritarian spirit, Mushakōji’s intentional community pledged itself to an ideal of “harmony without hierarchy.”18 Years earlier, Mushakōji had written of an ideal future society, in which: “no temptation whatsoever will disturb the peace, and people will love one another untroubled by anger, deceit, rivalry, coercion, moral obligations, or censorship. Sincerity, joy, and solidarity will suffice to dispel all anxiety about clothing, food, and shelter.”19 In what sounds ironic but is in fact a serious attempt to bring about such an ideal community, the first and only “commandment” in Atarashikimura is a prohibition against making or following “commandments”: Hito ni meirei suru nakare; mata hito ni meirei sareru nakare (cited in Mortimer 2000, p. 29). Indeed, the statutes of the community were remarkably “liberal” in emphasis: individual liberty over authority, personal initiative over compulsion, and “work” as a natural, pleasurable activity rather than an obligation (these features also align with some anarchist and syndicalist visions of the ideal society). In short, the village was more of a “co-operative” than a “commune.”

Of all the narodniki and utopians discussed in this chapter, Mushakōji appears to be the one least influenced by Buddhist ideas or practices. In this passage of his autobiographical novel Aru otoko (A certain man, 1923) he recounts the dreams of his early school years:

Why not become a bonze?—he even went so far to think; but then, to picture himself busy at chanting sutras was just too ridiculous. A beggar, then? But he did not believe that a beggar’s job would help to revive his selfhood. Whatever he chose to do, he would never settle for half-way solutions. He had to become a fully mature independent man of nothing at all. But again, even if he succeeded in bringing to life one side of the self, he thought he would not be able to revive the whole.(cited in and translated in Mortimer 2000, p. 20)

These reminiscences are interesting in several respects. First, though Mushakōji is reflecting from the age of forty back upon a period thirty years previous (around the time of the Russo-Japanese War), these dreams and doubts would stay with him throughout his life. Second, while he clearly rejects the traditional, stereotypical life of the Buddhist “bonze,” his aspirations for an “independent” and comprehensive “revival” of the self coincides perfectly with several streams of Buddhist modernism emerging in late Meiji, including New Buddhism and, perhaps even more so, the seishinshugi of Kiyozawa Manshi. Moreover, there are Zen inflections to Mushakōji’s conviction that: “One endeavors to work not simply to gain a livelihood, but as a way of enriching one’s life” (Shigoto ni hagemu no wa, seikatsu no tame dake de naku, jibun no jinsei jūjitsu suru koto desu) (cited in Matsubara 1994, p. 58). Indeed, more than one scholar has noted the “Daoist Zen” aspects of his poetry.20

Finally, even while Mushakōji’s youthful ardor for Christianity—stoked by reading Tolstoy and hearing lectures by Christian socialists Uchimura Kanzō and Kinoshita Naoe (1869–1937)—would cool under the influence of Belgian playwright Maurice Maeterlinck (1862–1949), he would confess in 1911 that he retained something like a “religious vocation.” Indeed, this passage from his essay “Jiko no tame no geijutsu” (Art for the self) bears quoting in full, as it points to a conception of self and society that was widespread among Taishō intellectuals, especially those under Tolstoy’s influence:

If I happened to be carried away by my social instinct, I might even be ready to die for my society. But if I am not and am pushed by society to expose myself against my will, I will hate to do so right away. Before I know whether it is good or bad to follow my social instinct, I must first listen to my individual, human, animal, terrestrial, Ding an Sich and all other instincts within me (I also perceive in myself something like a religious vocation; Tolstoy calls it “reason,” but I think it corresponds to something deeper than that).21

In this respect, it is useful to briefly examine Mushakōji’s Life of Shakyamuni Buddha, a 1934 publication that, due to positive critical reception and brisk sales, helped him to recover from the serious financial straits to which he had fallen by the late 1920s. In an afterword in which he explains his reasons for writing this work, Mushakoji notes that, while not intending to bring forth a “new Shakyamuni,” he wants to emphasize the “human” Sakyamuni, an ideal figure lauded for his combination of insight and compassion, yet one who possessed a natural innocence: “the heart of a child” (akago no kokoro).

In short, like Christ—also “a man with a pure, pure heart”22—Sakyamuni Buddha represents one of the great sages of the past; that is, his story is useful as a reference for ideal human behavior, but bereft of any transcendental or mystical gloss (see Mortimer 2000, p. 93, n. 4). As with many progressive Buddhists from late Meiji, including the New Buddhist Fellowship, Mushakōji created a pantheon of “masters,” including religious figures, philosophers, and writers (and even literary characters), who serve as models of human “liberation.”23 Thus “the Buddha” functions as a representative of a complex of humanist ideals, including a religious understanding rooted in common sense and compatible with modern science, one that rejects social discrimination and institutional hypocrisy, and looks to nature itself as a source for liberation.24 In his much earlier play Washi mo shiranai (I don’t know, either, 1910), Mushakōji presents a conversation between God, Jesus, and Sakyamuni in which they all admit their inability to save mankind—indicating, once again, a modernist perspective on spiritual liberation rooted in the individual as well as nature, but not “the gods.”25

3. Ideology and Utopia in the Taishō Period

In order to theorize further about the various Tolstoyan-Buddhistic utopias described in this chapter, I turn now to a brief discussion of the distinction between “ideology” and “utopia” in the work of 20th century German social theorist Karl Mannheim (1893–1947). In his classic 1929 work, Ideologie und Utopia (Ideology and utopia), Mannheim first delineates the “utopian mentality” as that which is always incongruent with the world—that is, “oriented toward objects which do not exist in the actual situation.” He then proceeds to distinguish utopian incongruity from ideological incongruity. Whereas the latter may also “depart from reality” in thought, it does not go so far as to effect change on society; rather, ideologies are eventually adopted or assimilated in support of the status quo. Thus, “[o]nly those orientations transcending reality will be referred to by us as utopian which, when they pass over into conduct, tend to shatter, either partially or wholly, the order of things prevailing at the time” (Mannheim 1936, p. 192) In short, for Mannheim, true utopias are always critical in the most fundamental sense of the term.

Mannheim goes on to contrast chiliastic forms of utopia—and the associated “mentality”—with liberal-humanitarian ones, which are rooted less in “ecstatic-orgiastic energies” than in “ideas.” In the liberal conception, a “formal goal projected into the infinite future” functions as a “regulative device in mundane affairs.” In other words, utopia is quite literally an idealized “other realm” that inspires us by working on or transforming our moral conscience. This general understanding underlies much of what we now call “modern philosophy,” and as such, was deeply intertwined with the political ideas of a particular class: the bourgeoisie, who consciously employed it against the “clerical-theological” view of the world.26 “This outlook, in accordance with the structural relationship of the groups representing it, pursued a dynamic middle course between the vitality, ecstasy, and vindictiveness of oppressed strata, and the immediate concreteness of a feudal ruling class whose aspirations were in complete congruence with the then existing reality.”27

Significantly, however, this liberal-bourgeois drive toward the “middle way” is pursued through a privileging of ideas above the vulgar materiality of “existing reality.” As a result, according to Mannheim: “Elevated and detached, and at the same time sublime, it lost all sense for material things, as well as every real relationship with nature.”28 In short, however utopian, a “moderate” path that ultimately privileges ideas over material reality contains a real danger of falling into a form of idealism that conforms to, rather than challenges, the material—and thus ideological—status quo. Again, a strong case could be made that modern Buddhism, along with most major religious traditions, has generally taken this path, either by design or, I would suggest, out of certain ideological tendencies inherent in interpretations of specific Buddhist teachings. In fact, this is precisely the central argument of the Critical Buddhist (hihan bukkyō) movement of the 1990s led by Hakayama Noriaki and Matsumoto Shirō, scholars affiliated with Soto Zen, though the Critical Buddhists did not extend their critique to a pervasive “liberal” mentality rooted in a discourse of modernity.29

As we have seen in the above discussion of various utopian experiments in the late Meiji and Taishō period, despite real differences, they are tied together by an overwhelming focus on self-discovery or self-awakening—understood less in relation to the role of the individual in society and politics than with respect to a broader and “aesthetic” concept of culture. This is not to say that all of these figures did not, to some degree, struggle with the “problem” of the self in relation to others and the larger community—indeed, the attempt to create sustainable intentional communities implies some degree of social concern. And yet, ultimately, resistance to the dangers of “vulgar materialism”—no doubt enhanced by legitimate fear of reprisal from authorities in the wake of the High Treason Incident—led to the search for, in Mushakōji’s phrase, “safe havens” (nigeba) in art, literature, and utopian communities, from the storms of politics and social conflict. Indeed, for Mushakōji, at least, the self becomes a sort of nigeba; as he explains in “Jiko no tame no geijitsu” (Art for the self, 1911):

Our present generation can no longer be satisfied with what is called “objectivism” in naturalist ideology. We are too individualistic for that… I have, therefore, taught myself to place entire trust in the Self. To me, nothing has more authority than the Self. If a thing appears white to me, white it is. If one day I see it as black, black is what it will be. If someone tries to convince me that what I see as white is black, I will just think that person is wrong. Accordingly, if the “self” is white to me, nobody will make me say it is black.30

Granted, Mushakōji is here expressing an extreme standpoint, a hyper-subjectivism that has no regard whatsoever for “objective truth”—or even, for that matter, reasoned discussion or debate. And yet, it speaks to a more general issue or problem with Taishō “progressivism,” and is precisely the reason that, after his initial excitement, progressive writer and economist Kawakami Hajime (1879–1946) left Itō Shōshin’s (1876–1963) utopian Muga-en (Garden of Selflessness) in 1906. Although neither Shōshin nor Nishida Tenkō (1872–1968) were artists or literary figures, both of their Tolstoyan-inspired intentional communities, Muga-en and Ittōen, can be classified as “liberal-humanist” in Mannheim’s schema. Extending this to contemporary criticism, the bulk of these Taishō progressive can be justly accused as relying on what Karatani (2005) Kōjin calls an “aesthetic” perspective, in which “actual contradictions” are surmounted and unified “at an imaginary level.” In Karatani’s sense, aesthetics is much more than simply a way of speaking about art and beauty; it is a mode of discourse that seeks to establish a reformed existence or “sensibility”—an understanding that dates back to Romantic writers such as Schiller, and finds expression within German Idealism following Hegel.31 For Karatani, the attempt by Japanese thinkers and utopians to “overcome modernity” inevitably ended in failure, since it is impossible to overcome the large-scale social contradictions and tensions of modernity by appealing to an abstract ideal of “culture.” With the hindsight of history, it becomes less surprising to note that many of these “progressive” experiments were easily co-opted by the emerging ultra-nationalism of the Shōwa period. The “resistance” that Mannheim sees as crucial to true utopian thought and practice thus slides into “ideology”—a justification and perpetuation of the status quo.

4. Conclusions

In this article, I have outlined several of the most notable experiments in utopian thought and practice in late Meiji and Taishō-era Japan, highlighting the eclectic nature of these experiments, as well as the near-universal debt to the work of Russian novelist and essayist Leo Tolstoy. In choosing to focus my analysis on two relatively understudied cases, those of Eto Tekirei and Mushakōji Saneatsu (rather than, say, Itō Shōshin or Nishida Tenkō), I have shown the diversity of thought that went into these “intentional communities,” despite the fact that both had Buddhist, socialist, and even Christian roots. Indeed, these two cases might be said to represent two poles on a spectrum of Taishō utopian thought. Whereas Mushakoji’s Atarashikimura falls squarely within the “liberal-humanist” utopia outlined by Mannheim, Eto Tekirei’s Hyakushō Aidōjō pushes against such residual idealism, in part by utilizing (Zen) Buddhist conceptions of practice to reaffirm the value of labor and, by extension, the material world. Here we see, I suggest, a lost opportunity for forging a critical utopia rooted in Tolstoyan, socialist and Buddhist ideals, one that may not have been able to “overcome” modernity but can be nonetheless read as an incipient non-western “altermodernity” along lines discussed by Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri.32

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Akamatsu, Katsumaro. 1981. The Russian Influence on the Early Japanese Social Movement. In The Russian Impact on Japan: Literature and Social Thought. Translated and Edited by Peter Bergen, Paul F. Langer, and George O. Totten. Los Angeles: University of Southern California Press, pp. 87–132. [Google Scholar]

- Calichman, Richard F. 2005. Introduction to Contemporary Japanese Thought. Edited by Richard F. Calichman. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Epp, Robert, ed. 1996. Long Corridor: The Selected Poetry of Mushakōji Saneatsu. Stanwood: Yakusha Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eto, Tekirei. 1925. Aru hyakushō no ie 或る百姓の家 (The household of a farmer). Tokyo: Manseikaku. [Google Scholar]

- Hardt, Michael, and Antonio Negri. 1994. Labor of Dionysus: A Critique of the State-Form. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hardt, Michael, and Antonio Negri. 2009. Commonwealth. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harootunian, Harry D. 1988. Things Seen and Unseen: Discourse and Ideology in Tokugawa Nativism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Havens, Thomas R.H. 1970. Kato Kanji and the Spirit of Agriculture in Modern Japan. Monumenta Nipponica 25: 249–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatani, Kōjin. 2005. Overcoming Modernity. In Contemporary Japanese Thought. Edited by Richard F. Calichman. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 101–118. [Google Scholar]

- Kinji, Tsukidate. 1974. Andō Shōeki no shishō keishōsha toshite no Eto Tekirei 安藤昌益の思想継承者としての江渡狄嶺 (Eto Tekirei as successor in thought to Andō Shōeki). In Andō Shōeki 安藤昌益. Edited by Shun’ichi Nishimura 西村俊一. Hachinohe: Ikichi shoin, pp. 145–71. [Google Scholar]

- Kohl, Stephen W. 1990. Abe Jirō and The Diary of Santarō. In Culture and Identity: Japanese Intellectuals during the Interwar Years. Edited by J. Thomas Rimer. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kołakowski, Leszek. 2008. Main Currents of Marxism: The Founders, the Golden Age, the Breakdown. New York: W.W. Norton, 3 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Konishi, Sho. 2013. Anarchist Modernity: Cooperatism and Japanese-Russian Intellectual Relations in Modern Japan. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mannheim, Karl. 1936. Ideology and Utopia. New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, Steven G. 2003. How Russians Shaped the Modern World: From Art to Anti-Semitism, Ballet to Bolshevism. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara, Taidō. 1994. Bukkyō o hiraku kotoba 仏教をひらく言葉 (Words to discover Buddhism). Tokyo: Mizu shobō. [Google Scholar]

- Moiwa, Toyohira. 1981. Ichikō tamashii monogatari 一高魂物語 (Tale of an elevated soul). Tokyo: Kenbunsha. [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer, Maya. 2000. Meeting the Sensei: The Role of the Master in Shirakaba Writers. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- MSZ. (Mushakōji Saneatsu zenshū. 武者小路実篤全集 全). Tokyo: Shōgakkan, 1987–1991. 18 vols.

- Nakao, Masaki. 1996. Taishō bunjin to denenshugi 大正文人と田園主義 (Taishō writers and agrarianism). Tokyo: Kindai bungeisha. [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura, Shun’ichi. 1992. Nihon ekorojizumu no keifu 日本エコロジズムの系譜―安藤昌益から江渡狄嶺まで (A genealogy of Japanese ecologism: From Andō Shōeki to Eto Tekirei). Tokyo: Nōbunkyō. [Google Scholar]

- Nobori, Shōmu. 1981. Russian Literature and Japanese Literature. In Nobori Shōmu and Akamatsu Katsumaro 赤松克麿, The Russian Impact on Japan: Literature and Social Thought. Translated and Edited by Peter Bergen, Paul F. Langer, and George O. Totten. Los Angeles: University of Southern California Press, pp. 21–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ohnuki-Tierney, Emiko. 1994. Rice as Self: Japanese Identities through Time. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rimer, J. Thomas, ed. 1990. Kurata Hyakuzō and the Origins of Love and Understanding. In Culture and Identity: Japanese Intellectuals during the Interwar Years. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 22–36. [Google Scholar]

- Saitō, Tomomasa, Nakajima Tsuneo, and Kimura Hiroshi. 2001. Gendai ni ikiru Eto Tekirei no shisō 現代に生きる江渡狄嶺の思想 (Eto Tekirei’s thought and its relevance today). Tokyo: Nōbunkyō. [Google Scholar]

- Shields, James Mark. 2011. Critical Buddhism: Engaging with Modern Japanese Buddhist Thought. Richmond: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Shields, James Mark. 2017. Against Harmony: Progressive and Radical Buddhism in Modern Japan. Oxford and London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shifman, Aleksandr I. 1966. Torusutoi to nihon トルストイと日本 (Tolstoy and Japan). Tokyo: Asahi shinbunsha. [Google Scholar]

- Sibley, William F. 1968. Naturalism in Japanese Literature. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 28: 157–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Henry Dewitt, II. 1970. The Origins of Student Radicalism in Japan. Journal of Contemporary History 5: 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamamoi, Mariko Asano. 1998. The City and the Countryside: Competing Taishō ‘Modernities’ on Gender. In Japan’s Competing Modernities: Issues in Culture and Democracy, 1900–1930. Edited by Sharon A. Minichiello. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, pp. 91–113. [Google Scholar]

- Tetsuo, Najita. 2002. Andō Shōeki—The ‘Forgotten Thinker’ in Japanese History. In Learning Places: The Afterlives of Area Studies. Edited by Masao Miyoshi and Harry D. Harootunian. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Wada, Kōsaku. 2012. Baronteki sekai no kōzō: Eto Tekirei no tetsugaku 場論的世界の構造—江渡狄嶺の哲学 (The structure of a world of “place”: The philosophy of Eto Tekirei). Tokyo: Escom Shuppan. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Several sections of this article have been adapted, with modifications and elisions, from (Shields 2017); see esp. pp. 170–72; 183–88. |

| 2 | For a comprehensive study of Tolstoy’s impact in both Japan and China, see (Shifman 1966). |

| 3 | Indeed, as Marks notes, Japanese readers of Tolstoy tended to see him as familiar rather than exotic or mystical—the way he was usually seen in the West—and for various reasons treated him as “one of their own” (ibid., p. 124). |

| 4 | See Shizen to jinsei (Nature and human life, 1900) for Roka’s reflections on nature, and Mimizu no tawagoto (Gibberish of an earthworm, 1913) for his adoption of the Tolstoyan peasant lifestyle. See (Shifman 1996, pp. 68–76), for the correspondence between Roka and Tolstoy. |

| 5 | Ibid.; see also Moiwa 1981. The Russian word narodniki refers to a person associated with a loosely defined progressive social movement that first arose in Russia in the 1860s and 1870s, in response to the poverty and social problems unleashed by of Tsar Alexander II’s “emancipation” of the serfs. The ideology developed and promoted by the narodniki was a form of populism, focused especially on addressing the grievances of rural peasants—still the vast majority of ordinary Russians—rather than urban workers. For more on the Russian narodniki, see (Kołakowski 2008, pp. 609–12). |

| 6 | Musashino would become the center of the Japanese narodniki movement, with Tokutomi Roka, Ikeda Taneo (1897–1974), and Ōnishi Goichi (1898–1992) all spending some time in the Kamitakaido area during the Taishō period. See (Nishimura 1992, p. 151). |

| 7 | See (Nishimura 1992, pp. 173–74). Tekirei referred to his utopian experiment as Tenshinkei, which is borrowed from Shōeki’s trope of the natural order as “movement,” “truthfulness,” and “reverence”; see (Tetsuo 2002, “Andō Shōeki,” pp. 75–76). |

| 8 | (Nishimura 1992, pp. 88–89); for an analysis of the life and work of Katō Kanji vis-à-vis the emergence of nōhonshugi, see (Havens 1970). |

| 9 | Tekirei writes about this in his correspondence with Akegarasu Haya in the Buddhist journal Chugai Nippō (March–April 1916); see (Wada 2012, pp. 293–94). |

| 10 | (Tetsuo 2002, p. 70). For more on Tekirei’s use of Shoeki, see (Kinji 1974). |

| 11 | Cited in (Nishimura 1992, p. 150); my translation. |

| 12 | Cited in (Wada 2012, p. 20); Lotus Sutra, chap. 12 “Devadatta.” |

| 13 | Ibid., pp. 285–86. |

| 14 | Attending Gakushūin through virtually the entire fourth decade of Meiji (1898–1906), Mushakōji and his Shirakaba peers were exposed to an impressive array of lecturers, including Natsume Sōseki (1867–1916), Uchimura Kanzō, Miyake Setsurei (1860–1945), Shimazaki Tōson (1872–1943), and Tokutomi Roka. |

| 15 | From Mushakōji’s autobiographical novel Aru otoko (1921–1923); translated in (Mortimer 2000, p. 19). |

| 16 | This relentless optimism can be seen in the titles of a number of Mushakōji’s works from this period: the novels Kōfukumono (A happy man, 1919) and Yūjō (Friendship, 1920), and the play Ningen banzai (Three cheers for mankind, 1922); also see his autobiographical novel Aru otoko (A certain man, 1923). |

| 17 | (Mortimer 2000, pp. x–xi). Admittedly, it is unclear whether these points represent Mortimer’s own scholarly opinion or are meant to reflect the “standard reading” of the Shirakaba writers by postwar (Marxist-inclined) critics such as Honda Shūgo. While at Gakushūin, Mushakōji notes that he and his peers were exposed to the early writings of Kotoku Shūsui and Sakai Toshihiko (1871–1933), and that he himself felt a particular affinity to Shūsui’s ideas, “never miss[ing] a single issue of the Heimin Shimbun” (MSZ (1987–1991) 15: 545). |

| 18 | In Aru otoko, Mushakōji notes his distrust of charismatic revolutionary leaders such as Lenin and Trotsky, who had become “cult-figures” and “idols” (MSZ (1987–1991) 5: 281). |

| 19 | Mushakōji, “Gendai no bunmei”; cited and translated in (Mortimer 2000, p. 29). |

| 20 | See, e.g., (Epp 1996, pp. 18–22). According to Epp, “Taoist equanimity lies at the heart of Mushakōji’s poetic” (18). |

| 21 | “Jiko no tame no geijutsu,” Shirakaba 1911 (MSZ (1987–1991) 1: 429); translated in Mortimer 2000, 91. Mortimer notes the Kantian and especially Freudian ring of these “instincts” (honnō). |

| 22 | MSZ (1987–1991) 9: 334–35. In his Kofuku mono (1919), published soon after the birth of Atarashikimura, Mushakōji would employ the term magokoro—literally, pure, open mind/heart—to refer to this characteristic shared by all true “masters.” Mortimer 2000, p. 180, 184, connects magokoro to a concept of “divine nakedness,” as well as to an “immanentist and pantheistic” energy that exists within nature. |

| 23 | For the Shirakaba writers, these included Christ, Śākyamuni Buddha, Confucius, St. Francis, Rousseau, Carlyle, Whitman, and William James; see (Mortimer 2000, p. 119). |

| 24 | See ibid., p. 120. Mortimer argues that because the Shirakaba “master” ultimately rejects all “isms,” the method of the master involves a (Zen?) “way of unlearning.” |

| 25 | Here again we see a parallel with Andō Shōeki’s radically “horizontal” perspective on liberation; i.e., one that rejects “authority” in any vertical form, relying rather on the “movement” of the individual within nature and community. |

| 26 | Ibid., p. 221. |

| 27 | Ibid., my emphasis. |

| 28 | Ibid., p. 222. |

| 29 | For an extended treatment of Critical Buddhism, see (Shields 2011). |

| 30 | Shirakaba, July 1911 (MSZ (1987–1991) 1: 428). |

| 31 | This is not to say that Karatani’s definition is equivalent to that of Schiller or Hegel, but rather that, like theirs, it looks to the original meaning of the Greek root aisthesis (aisthēsis), i.e., “perception.” See (Calichman 2005, p. 27). |

| 32 | According to Hardt and Negri, “altermodernity” marks conflict with modernity’s hierarchies as much as does antimodernity but orients the force of resistance more clearly towards an autonomous terrain” (Hardt and Negri 2009, p. 102). In an earlier work, Hardt and Negri developed a similar idea in the context of a discussion of the role of materialism in western thought: “[M]aterialism persisted through the development of modernity as an alternative … The vis viva of the materialist alternative to the domination of capitalist idealism and spiritualism was never completely extinguished” (Hardt and Negri 1994, p. 21). See also (Konishi 2013, pp. 3–4). |