From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Stanwood Cobb

Born November 6, 1881

Newton, Massachusetts

Died December 29, 1982 (aged 101)

Chevy Chase, Maryland

Occupation Educator

Nationality American

Period 1914–1979

Genre non-fiction, poetry and religious

Subject Education and Baháʼí Faith

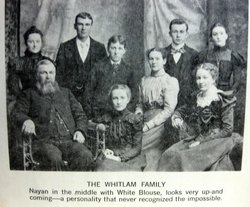

Spouse Ida Nayan Whitlam

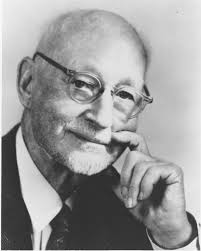

Stanwood Cobb (November 6, 1881 – December 29, 1982) was an American educator, author and prominent Baháʼí of the 20th century.

He was born in Newton, Massachusetts, the son of Darius Cobb and his wife, née Laura Mae Lillie. Darius and his twin brother Cyrus Cobb were Civil War soldiers and artists, and descendants of Elder Henry Cobb of the second voyage of the Mayflower. Their mother was Eunice Hale Waite Cobb, founding president of the Ladies Physiological Institute of Boston. Darius Cobb and his wife had four daughters and three sons.[1] Stanwood Cobb studied at Dartmouth College, where he was valedictorian of his 1903 or 1905 graduating class, and then at Harvard Divinity School, earning an A.M. in philosophy and comparative religion 1910.[2][3][4] His thesis work, Communistic Experimental Settlements in the USA, observed that every such settlement had failed within a generation because of an inability of communism to get people to subordinate their own desires for the good of the group.[5] In 1919 he married Ida Nayan Whitlam.[2] Cobb was a member of several literary associations[2] and of the Cosmos Club of Washington, D.C.[4]

Cobb lived internationally for some years before settling in Chevy Chase, Maryland, where he died.

Career as educator[edit]

In 1907–1910, Cobb taught history and Latin at Robert College in Constantinople (now Istanbul), followed by several years teaching in the US and Europe.[2] He later headed the English department at St. John's College in Annapolis, Maryland (1914–15), taught at Asheville School in Asheville, North Carolina (1915–16), and was instructor in history and English at the United States Naval Academy (1916–19).[2] Frustrated by the teaching experience at the Academy, Cobb heard a lecture by Marietta Johnson who helped marshal and crystallize his thoughts on education practice and curriculum theory.[6] As a result, in 1919, Cobb founded the Chevy Chase Country Day School, of which he was the principal until his retirement,[2] and, active in the progressive education movement in the United States, became a founder and motivating force,[6] first secretary, and eventually president (1927–1930)[2] of The Association for the Advancement of Progressive Education, in 1931 renamed Progressive Education Association (PEA) and then American Education Fellowship.[7][8][9][10] The first president was Arthur E. Morgan.[11] Later the influential John Dewey served as president.[12] Cobb resigned the presidency in 1930 following the influx of supporters of George Counts who moved the focus of the Association from a student-centered learning approach to one of a social policy oriented approach to education theory.[11] However, between the enormous impact of World War II on all thought and the involvement of many members of the PEA in communism and the general atmosphere of Anti-communism in the United States the achievements of the PEA both before Cobb's resignation and after were largely lost.[6]

Life as a Baháʼí[edit]

After looking at Theosophy and Reform Judaism and other themes in religion'[13] Cobb investigated the Baháʼí Faith after a series of articles in the Boston Transcript on the religion attracted his attention. He pursued the interest to Green Acre conference center in Eliot, Maine in 1906 during his studies at Harvard Divinity School preparing for the Unitarian ministry. Sarah Farmer much affected Cobb,[13] and Thornton Chase was giving a series of talks.[14] It was on that occasion that Cobb became a Baháʼí.[4]

Between 1909 and 1913 he met with ʻAbdu'l-Bahá five times (twice in Akka and several times during the latter's travel to Europe and the US).[4][15] In 1911 Cobb and a number of others gave talks in honor of the personal invitation by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá to pilgrimage of Louis Gregory.[16]

Cobb was a founding member of the Spiritual Assembly of the Baha'is of Washington D. C. in 1933, and served on various committees (for example Cobb was Chairman of the Teaching Committee in 1935[17]) and edited two Baha'i journals: Star of the West in 1924, and World Order from 1935–39.[4]

Books and articles authored[edit]

Cobb was a prolific writer. Among his books were:The Real Turk. 1914, The Pilgrim Press, ISBN B000NUP6SI.

Ayesha of the Bosphorus. 1915, Boston Murray and Emery Co.

The Essential Mysticism. 1918, Four Seasons, (republished 2006 by Kessinger Publishing, LLC as ISBN 978-1-4286-0910-5).

Simla, A Tale of Love. 1919, The Cornhill Company.

The New Leaven: Progressive Education and Its Effect upon the Child and Society. 1928, (Guy Thomas Buswell review published in The Elementary School Journal, Vol. 29, No. 3 (Nov., 1928), pp. 232–233)..

The Wisdom of Wu Ming Fu. 1931, Henry Holt and Company.

Discovering the Genius Within You 1932, John Day Publisher, and again, World Publishing Co., Cleveland, 1941.

New Horizons for the Child. 1934, Avalon Press.

Security in a Failing World. 1934, Avalon Press.

The Way of Life of Wu Ming Fu. 1935 (reprinted 1942), Avalon Press.

Character - A Sequence in Spiritual Psychology. 1938, Avalon Press.

Symbols of America. 1946, Avalon Press.

Tomorrow and Tomorrow. 1951, Avalon Press.

The Donkey Or the Elephant. 1951, Avalon Press.

What is Man?. 1952.

Sage of the Sacred Mountain; a Gospel of Tranquility. 1953, Avalon Press.

Magnificent Partnership. 1954, Vantage Press Publisher (Warren S. Tryon review published in The New England Quarterly, Vol. 28, No. 3 (Sep., 1955), p. 429).

What is God?. 1955, Avalon Press.

What is Love?. 1957, Avalon Press.

Islamic Contributions to Civilization. 1963, Avalon Press.

Memories of ʻAbdu'l-Baha. 1962, Avalon Press.

The Importance of Creativity. 1967, Scarecrow Press.

Life With Nayan. 1969, Avalon Press.

Radiant Living. 1970, Avalon Press.

The Meaning of Life. 1972, Avalon Press.

Thoughts on education and life. 1975, Avalon Press.

A Call to Action: Develop Your Spiritual Power : Man's Fulfillment on the .... 1977, Avalon Press.

A Saga of Two Centuries 1979 (autobiography).

Similar to his books, the focus of Cobb's articles has been education and Baha'i oriented - he has contributed to or was anthologized by:The Atlantic Monthly (Feb 1921)

The Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research by the American Society for Psychical Research,

The School Arts Magazine by Davis Press,

Childhood Education by the Association for Childhood Education International

Child Study by Child Study Association of America

The New England Magazine by the Making of America Project

The Path of Learning: Essays on Education by Henry Wyman Holmes, Burton P. Fowler, Published 1926 by Little, Brown and Company

Progressive Education by Progressive Education Association

as well asThe Baháʼí World (see Baha'i Periodicals for information)

World Order

See also[edit]Baháʼí views on Communism

Education reform

G. Stanley Hall

International Journal of Progressive Education

References[edit]

^ The Register of the Malden Historical Society Vol 6, 1919-20 by Mass Malden Historical Society, Frank S. Whitten Printer, p.70-3

^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g John F. Ohles, ed. (1978). Biographical Dictionary of American Educators. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 275–6. ISBN 978-0-313-04012-2.

^ McLean, J.A., Pilgrim's Notes (blog), "What Stanwood Cobb Told Me About ʻAbdu'l-Bahá," Sunday, August 12, 2007

^ Jump up to:a b c d e The Baháʼí World, Vol 18, Part 5, "In Memoriam: Stanwood Cobb, 1881–1982"

^ Cobb, Stanwood (1979). A Saga of Two Centuries. Washington, DC: Avalon Press. p. 33.

^ Jump up to:a b c Alternative Schools: Diverted but not Defeated Paper submitted to Qualification Committee, At UC Davis, California, July 2000, By Kathy Emery

^ Historical Dictionary of American Education ed. by Richard J. Altenbaugh, 1999 Greenwood Press Publisher, Progressive Education Association by Craig Kridel, p.303-4, ISBN 0-313-28590-X

^ University of Minnesota College of Education and Human Development, "Timeline: 1910s" Archived 2008-05-06 at archive.today

^ Time Magazine, "Progressives' Progress," Monday, Oct. 31, 1938

^ Beck, Robert H. 1959. "Progressive Education and American Progressivism: Margaret Naumburg" (book review). Teachers College Record 60(4): 198-208

^ Jump up to:a b The Struggle for the American Curriculum by H. Kliebard, p. 168, published by Rutledge, 1955

^ Encyclopedia of Chicago - Progressive Education

^ Jump up to:a b Restless Souls: The Making of American Spirituality by Leigh Schmidt Cobb, published by HarperCollins, 2005, p. 218

^ Minutes of the House of Spirituality, 1 Sept. 1906

^ McLean, J.A., Pilgrim's Notes (blog), "Corrections to Blog on Stanwood Cobb...," Sunday, August 12, 2007

^ Biography of Hand of the Cause of God Mr. Louis George Gregory

^ Alain Locke: Faith and Philosophy by Christopher Buck, Studies in Babí and Baháʼí Religions - Volume 18, p.168

External links[edit]Works by or about Stanwood Cobb at Internet Archive

Association for Childhood Education International

It was during his lectures in the barn that he first spoke of `Abdu'l-Bahá, whom he had met on five occasions: twice in Akká in 1909 and 1910, later in Boston (1912), then in Washington (1912) and finally in Paris (1913). It was later at Green Acre, in old age, that he would give me his more personal impressions.

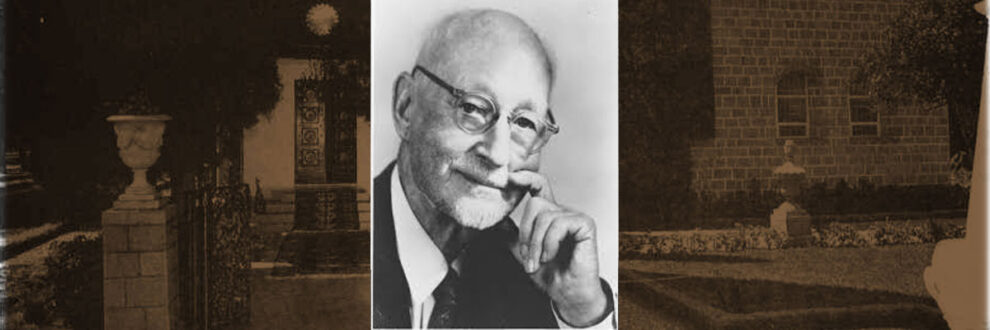

Stanwood Cobb

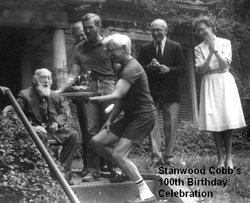

Stanwood CobbBorn: November 6, 1881

Death: December 28, 1982

Place of Birth: Newton, Massachusetts

Location of Death: Chevy Chase, Maryland

Burial Location: Rock Creek Cemetery, Washington, District of Columbia

Stanwood Cobb studied at Dartmouth College and was a valedictorian of his grauating class and then at Harvard Divinity School, he earned an A.M. in philosophy and comparative religion. He was an American educator, author and prominent Bahá’í.His parents were Darius Cobb and Laura Marie Lillie Cobb who both died in 1919.

On September 19, 1919 he married Ida Nayan Whitlam who was a member of several literary associationswho later died in 1967. They had no children.

On September 19, 1919 he married Ida Nayan Whitlam who was a member of several literary associationswho later died in 1967. They had no children.His father and his father’s twin brother Cyrus Cobb were Civil War soldiers and artists, and descendents of Elder Henry Cobb of the second voyage of the Mayflower. Their mother was Eunice Hale Waite Cobb, who was the founding president of the Ladies Physiological Institute of Boston. [1]

Although Stanwood’s books are no longer widely read in the Bahá’í community, he was a prolific writer, innovative teacher and international lecturer. He has well earned his place, if somewhat neglected, in the annals of Bahá’í history. I first came across Stanwood’s name in our family library. There Jack McClean discovered a few of his books, including Islamic Contributions to Civilization (1963), which gives a readable, economical overview of the contributions of Islam to world culture and civilization.

Jack first met Stanwood Cobb at Beaulac summer and winter school, a property north of Montreal in the beautiful Laurentian Hills, not far from Rowdon, Quebec. Jack was about 14 years old; Stanwood would have been about 72. (Circa 1959). When, years later, Jack paid him a visit at his cottage at the Green Acre Centre near Eliot, Maine in the summer of 1977, he had reached the advance old age of 96, but he was to live on for a few more years. Although he was somewhat frail by 1977, Dr. Cobb was still in reasonably good health, a condition that had been produced, not only by robust genes, but also by his life-long regimen of good hygiene, a program that included deep-breathing, meditation, dietary practices and exercise.

Beaulac had once been owned by the National Spiritual of the Bahá’ís of Canada but it was subsequently sold. It consisted of a two-story farm house, a barn that had been converted into a rustic lecture hall for larger meetings — it always retained the lingering odor of the cattle barn — cabins on both sides of the highway, a small lake, and acres of rolling hills. It was at lunch that Jack met Stanwood. He sat opposite. Time has not dimmed the memory of this colourful character. He was showing a faint growth of beard and, as he recalls, unlike photos of his later years, he was not wearing glasses, perhaps because he was returning from his morning swim.

Memories of `Abdu’l-Bahá: The Joy of Life

It was during his lectures in the barn that he first spoke of `Abdu’l-Bahá, whom he had met on five occasions: twice in Akká in 1909 and 1910, later in Boston (1912), then in Washington (1912) and finally in Paris (1913). It was later at Green Acre, in old age, that he would give me his more personal impressions. But during his barn lectures, Stanwood related some of the stories that were published in his memoir “Memories of `Abdu’l-Bahá.” However, the following observation was not found there. “Abdu’l-Bahá,” said Dr. Cobb, “was unlike the other spiritual leaders who came to Green Acre in this respect: He had a wonderful sense of humour and laughed out loud. It is this joy and zest for living that distinguished the Master from the other spiritual teachers there. They were much too serious. `Abdu’l-Bahá fully embraced the joy of life and encouraged his followers to do the same.”

It was at Beaulac that Stanwood told the story of how his father — “a venerable Boston artist 75 years of age,” a devoutly religious man — much to Cobb’s shock and horror, began to lecture the Master on the personal spiritual philosophy that was the fruitage of his mature years. There must have been something of the preacher in Mr. Cobb senior because Stanwood’s memoir says that his father, for no less than half an hour, “proceeded to lay down the law to `Abdu’l-Bahá.” But on this, as on other occasions, the younger Cobb witnessed `Abdu’l-Bahá’s graciousness and silent wisdom. In an unforgettable lesson, informed by infinite courtesy and humility, the Master listened patiently to the preachment, smiling all the while, “enveloping us with His love.” The unfailing wisdom of `Abdu’l-Bahá had correctly divined that Mr. Cobb Senior needed to empty his cup. Stanwood’s father came away from his encounter with `Abdu’l-Bahá fully satisfied this wonderful interview! [2]

Editor’s Note:

Please read Stanwood Cobb’s essay on The Continuity of Religion by clicking here.

Source:

1 Memorial. “Stanwood Cobb” findagrave.com: 39588913

2 McLean, Jack.“What Stanwood Cobb Told Me about ‘Abdu’l-Baha” Bahai-Library.org: Winters, Jonah

Images:

Baha’i World Centre Archives

Stanwood Cobb

W. Warder