Review

A bracing book from the fashionably wild thinker embraces anarchist and Buddhist ideas in an argument for solidarity with all that exists

Stuart JeffriesWed 23 Aug 2017

In 2015, Cecil the lion was shot with an arrow by a big-game hunting American called Walter Palmer. Facebook and Twitter erupted in outrage against the insouciant dentist, UN resolutions were passed, Palmer was stalked and his extradition to face charges in Zimbabwe demanded.

Timothy Morton takes Palmer’s flash-mob shaming as a hopeful sign. We may be living in dark times – the epoch he and other radical thinkers call the Anthropocene, in which our species has committed ecological devastation, presided over the sixth mass extinction event (animal populations across the planet have decreased by as much as 80% since 1900) and got our degraded kicks by offing lovely lions. But, in a dialectical twist, humans are becoming so aware of what we’ve done that we are now capable of bringing about change.

Morton sets out a political programme of liberating humans from the “patriarchal, hierarchical, heteronormative possibility space” that has constrained our species ever since our ancestors started farming in Mesopotamia 400 generations ago. It was then, he asserts, that humans started hubristically carving up the biosphere. Ever since, he contends, our very thinking has become rapaciously binary. Consider the Platonic distinction between body and soul. Consider Descartes’ implicit suggestion that other animals are furry robots. Consider what Dostoevsky saw when he visited Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace: he found in it a metaphor for western civilisation, an immune system that brought the world’s most diverting flora, fauna and industrial products under one roof, while whatever remained outside (war, genocide, slavery, unpleasant tropical diseases, human waste, expendable life forms) dwindled into irrelevance.

We have airbrushed out the historical disaster Morton calls “the Severing”, a name that gives his argument a voguish Game of Thrones-like vibe. “The Severing,” he explains, “is a catastrophe: an event that does not take place ‘at’ a certain ‘point’ in linear time, but a wave that ripples out in many dimensions, and in whose wake we are caught.” The severing resembles the central trauma of Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials novels. In that imagined world, children each have their daemons – until, that is, organised religion (evil Nicole Kidman in the film adaptation The Golden Compass) brutally severs the symbiotic pair in order to subjugate humanity. For Morton, our task is to become haunted beings again, possessed by a spectral sense of our connectedness to everything on this planet.

Cecil the lion in Hwange national park, Zimbabwe. Photograph: Reuters

Cecil the lion in Hwange national park, Zimbabwe. Photograph: ReutersHow might we do that? Morton here attempts to retool Marxism to accommodate oppressed non-humans. Tough gig: Marx’s thought is, you’d think, hopelessly anthropocentric, a philosophical artefact of the Severing. Morton demurs. His book is about adding “modes of anarchist thought back into Marxism, like the new medical therapy that consists of injecting fecal matter into another’s ailing guts”.

His fecal shock therapy sometimes seems like a quack cure, but one disarming aspect of Morton is his hopefulness. He loathes the smug leftist defeatism of his academic colleagues – their sense that capitalism won, that Earth is done, and all that remains is for self-serving professors to ringfence their critiques of neoliberalism and ecological ruination inside intellectual cordons sanitaires. In the Anthropocene, he realises, everyone is implicated. Even theory professors don’t have clean hands.

Against defeatism, he pits hope. The size and scope of the outrage over Cecil’s killing was, he argues, very different from, say, the Save the Whale protests of the 1970s. “The year 2015 was when a very large number of humans figured out they had more in common with a lion than a dentist,” he claims.

Without wishing to sound pre-fecally defeatist, though, I’m doubtful. I don’t think the reaction to Cecil’s killing suggests we have anything significant in common with lions. Rather, the flash-mob shaming might well be thought of as projected self-loathing premised on realising that Palmer is the barbarous flipside to what we call human civilisation.

'A reckoning for our species': the philosopher prophet of the Anthropocene

Read more

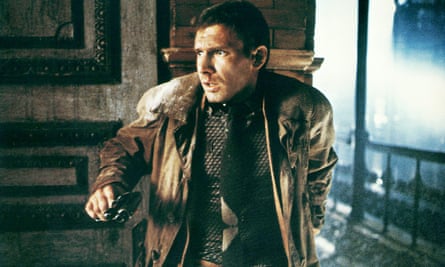

In his earlier book Dark Ecology Morton was on to something like this. He reflected that in Ridley Scott’s dystopian thriller Blade Runner, the protagonist Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford) comes to suspect he might be the enemy he has been ordered to hunt down. Humanity in the Anthropocene is like Deckard: we realise with – ideally, revolution-catalysing – horror that we are the problem.

There’s another possibility Morton too quickly dismisses. Zambia’s tourism minister Jean Kapata had a point when she suggested the reaction to Cecil’s slaying showed westerners care more about African animals than African humans. No matter. We should, Morton argues in this exasperating, beguiling, intellectually reckless and restless book, have solidarity with non-humans – not just with charismatic megafauna such as Cecil, but algae, cutlery, rocks. This follows from his adherence to object-oriented ontology, the argument that nothing has privileged status and philosophers exist equally with Xboxes and excrement.

That’s right – excrement. Even the stuff we throw away demands our solidarity. “The waste products in Earth’s crust are also the human in this expanded, spectral sense,” Morton writes. “One’s garbage doesn’t go ‘away’ – it just goes somewhere else.” Good point, though I’d like him to argue that point in front of those living through the second month of Birmingham’s refuse collectors’ strike this summer.

Morton’s garbage is like Freud’s return of the repressed, in that it comes back to bite us in the philosophical ass: what we excrete remains part of us, as do the plastic bottles on landfill sites we thought we’d got rid of. Even more chasteningly, he insists that humans are not just composed of stardust (as Joni Mitchell once suggested), but of viruses, rubbish and bacteria. One-third of baby milk, for instance, is not digestible by the baby; rather it feeds the bacteria that coats the intestines with “immunity-bestowing film”.

But how can we have solidarity with non-humans? One way, Morton suggests, is to abandon the anthropocentric idea that thinking is the leading communication mode. “Brushing against, licking or irradiating are ask access modes as valid (or as invalid ) as thinking,” he writes. If he really wants solidarity with Cecil and algae, he should publish – somehow! – an edition of Humankind that can be accessed by licking, floating through, brushing against.

‘Like Harrison Ford’s Deckard in Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner we realise with horror that we are the problem.’ Photograph: Sportsphoto Ltd/Allstar

‘Like Harrison Ford’s Deckard in Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner we realise with horror that we are the problem.’ Photograph: Sportsphoto Ltd/AllstarMorton, wonderfully, doesn’t balk at the nutty repercussions of his interdependence thesis (what he calls “implosive holism”). He asks at the outset: “Am I simply a vehicle for numerous bacteria that inhabit my microbiome? Or are they hosting me?” In what he calls the symbiotic real, it’s not clear who is host and who parasite. All this recalls how Montaigne thought himself out of anthropocentrism with his remark: “When I am playing with my cat, how do I know she is not playing with me?”

Morton, British-born professor of English at Rice University in Texas, is a fashionable thinker, the Montaigne of the Anthropocene – so much so that he was recently honoured with an appearance in Private Eye’s Pseuds Corner. True, he’s anathematised by philosophy departments for the wild thinking that makes him attractive to artworld hipsters such as Björk, Olafur Eliasson, Hans Ulrich Obrist and Philippe Parreno. And yes, he may be a hypocrite (he racked up 350,000 air miles last year while hectoring us non-non-humans on our ecological crimes). But his developing anarchic communism is bracing. Here he heretically argues that consumerism, far from marking humanity’s spiritual ruination (that default critique of our fate under late capitalism beloved of Frankfurt School miseryboots), might help promote ecological awareness, since it involves allowing ourselves to be haunted by things so that we can become the spectral humans he yearns us to be.

Morton's wild thinking has attracted Björk, Olafur Eliasson, Hans Ulrich Obrist and Philippe Parreno

Here too he suggests we scrap the concept of “nature” and reclaim the upper scales of ecological coexistence, rather than – as the blurb deliriously has it – let agrochemical company “Monsanto and cryogenically suspended billionaires define them and own them”. You don’t have to holiday at Center Parcs to realise that “nature” is a hyperreal simulation devised to blind us to the “agrilogistic” rape of the Earth, but it might help you get inside Morton’s mindset.

He is hardly the only philosopher to attempt to overcome anthropocentrism. Jeremy Bentham once devised an empathy test: “The question is not Can they reason?, nor Can they talk?, but Can they suffer?” Can rocks suffer? Frankly I don’t know. Maybe I should ask my bowel bacteria. What I do know is that for Morton that kind of test is anathema in his quest for solidarity with non-humans, since such utilitarianism is too mired in agrilogistic liberal economics to serve as revolutionary ally.

Instead, he borrows from Russian anarchist Peter Kropotkin the idea of “mutual aid” to flesh out of what he calls towards the end of the book “kindness”. Kropotkin detected kinship between how ants and beetles bury their dead and how working-class Russians co-operated. All act not out of empathy, but from something more basic which Morton describes as “the zero-degree cheapest coexistence mode, something you rely on when all else fails”. If this is kindness, Tim, it’s not kindness as I’ve hitherto known it.

Morton’s kindness is to do with being permeated by other beings, in recognising there is no inside-outside binary. The new human he yearns for passively allows him or herself to be infected by the healing solidarity of non-humans.

I struggle, too, with his theory of passivity with which he ends the book. He calls it “rocking”, and it derives from his reflections on Buddhism. “This theory of action has to do with a highly necessary queering of the theistic categories of active versus passive.” Rocking involves a quivering awareness of the interconnectedness of everything. We may think – in our heteronormative, hierarchical way – that rocks are inert, but really if we allowed ourselves to, we might realise that even rocks, well, rock. Morton isn’t talking about mindfulness – which he, I think rightly, takes as a lie to keep willing subjects working at being calm and thus keeping capitalism’s foot on our collective throat – but about a pleasantly mystic sensual communion with all that is.

How does passive rocking help bring about communism? Should we throw rocks at our oppressors or refrain from doing so because it would hurt their (the rocks’) feelings? I don’t know. I’m doubtful too whether Morton’s ardent book is sufficient to the moment in which any communism is outsmarted (maybe that should be outstupided) by Trump’s neoliberalism. But that’s probably because I’m hobbled by the very mindset Morton here excoriates, namely “retweeting the agricultural age religion that is gumming up our ways of imagining a different future”. Sorry for doing that, professor.

Humankind is published by Verso. To order a copy for £14.44 (RRP £16.99) go to guardianbookshop.com or call 0330 333 6846. Phone orders min. p&p of £1.99

=====