관상학

| 유사과학 pseudo-science |

|---|

|

| 유사과학의 문제점 |

| 유사과학의 분류 |

| 과거의 원형과학 |

| 사이비과학/반과학 |

| 논란의 대상 |

| 유사의학 |

| 정치 현상과 매개한 경우 |

| 유사과학 단체 |

관상학(觀相學, physiognomy)은 인간의 외양(특히 얼굴)을 가지고 그 사람의 성격 등을 파악하는 유사과학의 일종으로서, 과거에는 원형과학의 일종으로 볼 수도 있었다.

관상(觀想)의 원어 테오리아에는 관조(觀照), 관찰, 사자(使者) 파견, 제례(祭禮)와 구경이라는 뜻이 있다.

무엇인가를 '보는 것'으로서, 신이나 신상(神像)을 보는 종교적인 것에서 플라톤의 이데아의 미의 관조로 바뀌어 아리스토텔레스에서는 사물의 원리·원인을 본다――즉 안다는 것, 이론적 지식이 된다. 이것은 제작이나 행위와는 달라 그 자체가 목적이므로 상위(上位)에 속한다. 관상생활(학자의 연구생활 같은 것)은 신의 자기사유(自己思惟)와 흡사하여 행복이며 최고선이라고 한다.

2009년 New Scientist에 의하면 관상과 사람의 성격과는 아무런 연관이 없다는 점을 밝히며.[1] 관상학은 유사과학이라는 점을 밝혔다.[2]

역사[편집]

이는 본래 중국에서 발생하였다. 춘추시대(春秋時代)에 진(晋)나라의 고포자경(姑布子卿)이 공자(孔子)의 상을 보고 장차 대성인(大聖人)이 될 것을 예언하였으며, 전국시대(戰國時代)에 위(魏)나라 사람 당거(唐擧)도 상술(相術)로 이름이 높았으나 상법(相法)을 후세에 남긴 것은 없다.

남북조시대(南北朝時代)에 남인도에서 달마(達磨)가 중국으로 들어와 선불교를 일으키는 동시에 '달마상법'을 후세에 전하였다. 그 후 송(宋)나라 초기에 마의도사(麻衣道士)가 '마의상법'을 남겼는데, 관상학의 체계가 이때에 비로소 확립되었다.[출처 필요] '달마상법'과 '마의상법'은 관상학의 쌍벽을 이룬다. 관상학이 한국에 들어온 것은 신라시대이며, 고려시대에는 혜징(惠澄)이 상술로 유명하였다.[출처 필요] 조선시대에도 끊임없이 유행하여 오늘에 이른다.

같이 보기[편집]

참조[편집]

| 위키미디어 공용에 관련된 미디어 분류가 있습니다. |

- ↑ “How your looks betray your personality”. 《New Scientist》 (2695). 2009년 2월 11일.

- ↑ ^ a b c d e f Roy Porter (2003). "Marginalized practices". The Cambridge History of Science: Eighteenth-century science. The Cambridge History of Science 4 (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 495–497. ISBN 978-0-521-57243-9. "Although we may now bracket physiognomy with Mesmerism as discredited or even laughable belief, many eighteenth-century writers referred to it in all seriousness as a useful science with a long history(...) Although many modern historians belittle physiognomy as a pseudoscience, at the end of the eighteenth century it was not merely a popular fad but also the subject of intense academic debate about the promises it held for future progress."

===

Physiognomy

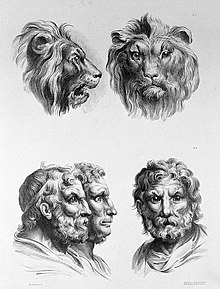

Physiognomy (from the Greek φύσις, 'physis', meaning "nature", and 'gnomon', meaning "judge" or "interpreter") or Face Reading is the practice of assessing a person's character or personality from their outer appearance—especially the face. The term can also refer to the general appearance of a person, object, or terrain without reference to its implied characteristics—as in the physiognomy of an individual plant (see plant life-form) or of a plant community (see vegetation).

Physiognomy as a practice meets the contemporary definition of pseudoscience[1][2][3] and it is so regarded among academic circles because of its unsupported claims; popular belief in the practice of physiognomy is nonetheless still widespread and modern advances in artificial intelligence have sparked renewed interest in the field of study. The practice was well-accepted by ancient Greek philosophers, but fell into disrepute in the Middle Ages while practised by vagabonds and mountebanks. It revived and was popularised by Johann Kaspar Lavater, before falling from favour in the late 19th century.[4] Physiognomy in the 19th century is particularly noted as a basis for scientific racism.[5] Physiognomy as it is understood today is a subject of renewed scientific interest, especially as it relates to machine learning and facial recognition technology.[6][7][8] The main interest for scientists today are the risks, including privacy concerns, of physiognomy in the context of facial recognition algorithms.

Physiognomy is sometimes referred to as 'anthroposcopy', a term originating in the 19th century.[9]

===

===

===