1] How Toshihiko Made Me Understand Islam

Monira Al Qadiri

008 / 26 February 2015

View author information

Download PDF

Who would have thought that the best translation ever to be conducted of the Qur'an was actually in Japanese? Many scholars agree that Toshihiko Izutsu's 1958 version of the holy book is one of the most accurate one available.[1] A linguistic genius, Dr. Izutsu finished reading the entire Qur'an just one month after beginning to learn Arabic. His idiosyncratic method of analyzing theology through language (his background knowledge of Zen Buddhism assisted this advanced outlook on other world religions) produced incredible insights into Islam that I have not heard with quite the same level of clarity and objectivity from any other scholar. Later in life, he went on to teach Islamic philosophy at several universities in Tehran, which hints at just how knowledgeable he became of the religion and its history.

Monira Al Qadiri, Sulaibikhat Cemetery, Jaafari (Shiite) side, 2007.

Copyright and courtesy the artist.

Regrettably, many of his thought-provoking books have remained un-translated, and are only accessible in Japanese. Fortunately for me, my fluency in the Japanese language allowed me to penetrate this rare dearth of significant research with ease. When I first read his lecture-turned-book Islamic Culture (1991), everything in my life suddenly made sense. In my ten years living in Tokyo, it was by far the moment I felt most satisfied to have mastered Japanese.

Izutsu effortlessly demonstrated how the Qur'an was written in the prophet's own dialect (Quraishi); that the religion had many traits of the language of the marketplace (the prophet himself was a merchant); that the relationship between God and his subjects was a vertical relationship of a master and his slave ('Abd) also stemming from the market (Souk); that Islam follows a distinctly capitalist mentality (good deeds are referred to as 'earnings' and are counted, like money); that the scripture was written in the first person – in God's own words – an anomaly compared to other faiths; that Islam discarded with figurative representation because its language itself was the audio-visual medium (the 'images' are inside the words), making it one of the only truly 'abstract' religions. Indeed, the Qur'an refers to paganism, which preceded it, as 'that which does not see or hear.'[2]

After finishing Islamic Culture, I came to this conclusion: Islam is abstract expressionism through poetic illustration.

Like abstract expressionism, it is concerned with describing spiritual matters of the mind and soul by denying pedagogical figurative depictions (sometimes very violently so, by actively destroying pagan statues and objects), and pushing religious creativity beyond the superficial through the medium of language. If embodied pictures and figures are no longer necessary and are instead encapsulated within 'words' – oral or written – their ability to transcend physical spaces and material 'things' in general becomes infinite. The Qur'an is 'full of visual images from corner to corner'[3] that can simply materialize in the expansive arena that is the mind. It gives the believer (the viewer if spoken from an artistic standpoint) the luxury and space to imagine the visuals through the power of literary suggestion alone.

Monira Al Qadiri, Sulaibikhat Cemetery, Sunni side, 2007.

Copyright and courtesy the artist.

We usually attribute the philosophical structure of these artistic concepts such as visual abstraction to western modern art movements in the twentieth century. But in actual fact, they have been processed and developed through and within literary movements centuries before the advent of modernism. In the Arab world especially, literature and language were and remain the primary means of artistic expression, and have been so for centuries. It must be taken into account that part of this trend is strongly influenced by Islam as an institution of thought, and its philosophical developments over the years. It is only very recently that visual figurative art has become widespread in the region, which coincides with an enthusiastic attitude towards modern, individualistic, urban life.

However this city-dwelling lifestyle does not conflict with Islamic teachings. Izutsu also stressed that Islam was not the religion of the desert, and was based on a truly urban understanding of the world. As noted above, distinct aspects of city life (the market, money, slavery etc.) are apparent in the phrases and words used to describe religious concepts within the Qur'an. This fusion of natural and man-made environments with theology stunned my imagination. But here, I began to wonder – what if this urban disposition of Islam had changed in recent times? After some contemplation, I came to the realization that it has indeed changed dramatically. The advent of Wahhabism in the Arabian peninsula over the past two centuries has succeeded in returning Islam to the desert.

A large section of the book Islamic Culture is dedicated to deciphering the different prisms used to interpret the Qur'an, and how these prisms can become completely contradictory depending on their placement in the wider sphere of the Islamic Empire over time. Wahhabism – the official Sunni sect adopted by Muhammad Ibn Saud (the ancestor of the House of Saud, founders of modern-day Saudi Arabia) contains many traits of a desert mentality. And although initially a fringe sect, it is now the dominant expression of Sunni Islam in the Arabian peninsula, even though official accounts claim otherwise. Senior religious clerics state that this is the natural and ubiquitous form of Sunni Islam that permeates the entire Islamic world, but this is in fact a false claim. Sunnism is not quite as puritan or extreme as Wahhabism, and has many pluralistic interpretations of it existing all over the world. Nevertheless, Wahhabism's teachings have penetrated the culture of the Arabian Gulf far beyond the local populace's immediate comprehension.

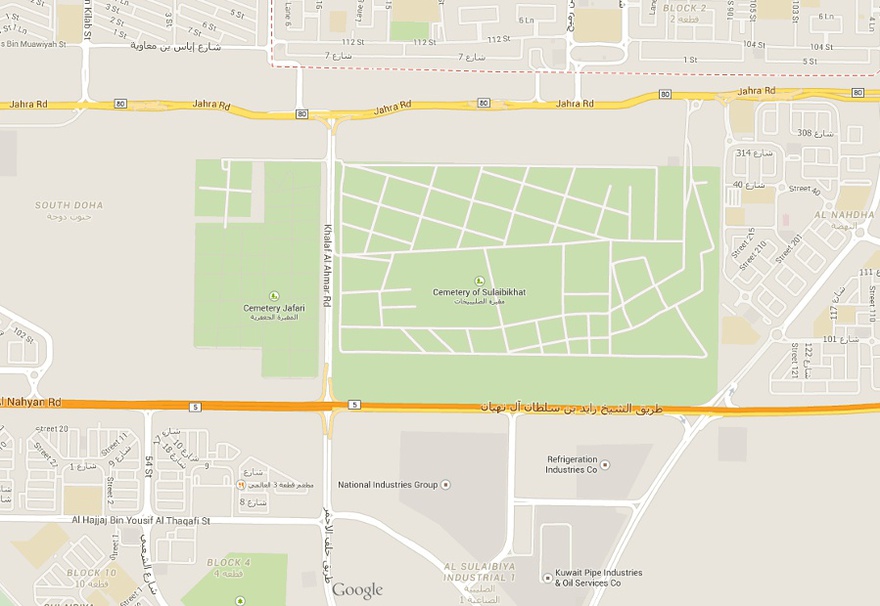

Sulaibikhat cemetery map, map data.

©2015 Google.

One of Wahabbism's signature commandments is 'do not visit the dead', because such shrine or tomb visitations can inspire idolatry. The deceased must be forgotten, and their graves must remain unnamed, as is the case in desert life; you must not cry or show emotion over those who have left us. It is this kind of harsh puritanism that entails the desperate climatic surroundings of the desert, unlike Shi'ism for example, where the dead are revered and decorated in a Firdous-like (Garden of Heaven) atmosphere, and graves are blessed with sweets and water. Izutsu claims that Shi'ism is a fundamentally esoteric sect that is heavily influenced by Persian culture, where belief in symbolism and meaning are paramount, often embracing metaphysical concepts like the disappearance of the twelfth Imam Mehdi into a hole in time, and his subsequent reappearance before the day of judgment. This comes in opposition to Sunnism, which is an exoteric sect based mostly on personal conduct and behaviour: 'Shi'ism is illusionary surrealism, while Sunnism is atomistic realism.'[4]

Being half Sunni and half Shi'ite myself, these insights into the cultural difference of sects profoundly articulated my understanding of my familial background. The stark contrast between my ancestral Iranian and Saudi roots; the discrepancies between both of my families' beliefs, customs, and rituals could only be explained through Izutsu's sharp observations. I realized that there is a place where this phenomenon is most apparent: Sulaibikhat.

Sulaibikhat is the national cemetery in Kuwait (the only one currently in use) that was built around the early 1960s. On the one side of the cemetery is the Shi'ite graveyard, and on the other is the Sunni (Wahhabi) one. They are segregated only by a road cutting through the middle of the two graveyards.

Sulaibikhat cemetery satellite image.

Imagery ©2015 CNES / Astrium, DigitalGlobe.

Could this road be seen as the violent separation between the spiritual manifestations of Islam? Is this the border of irreconcilable, intolerable cultural difference? As is evident in the following maps and images, the doctrinal divisions are visually clear. The Shi'ite decorated garden is on the left, the nameless Sunni desertscape is on the right. It is as if a completely opposing philosophy on life and death can literally be 'pictured' here, without exerting any effort to uncover it. The banal asphalt path between the cemeteries transforms itself into the metaphysical boundary of thought, and neatly partitions these incompatible world views.

At the time when I was observing the discrepancies of these cemeteries, I was in the middle of conducting my research on the aesthetics of sadness in the region, and trying to uncover how grief is visually manifested within physical spaces (most of which were tombs and cemeteries) as a first entry into the subject. After much reflection on the difference of the two plots, I could not come to a definitive answer as to which one was more 'sad', so to speak. Is the beautiful celebration of death and constant visitation of graves on the left side more 'tragic' somehow, or the denial of remembrance of the dead on the right side more bereaved because of its abject sorrow at even the fleeting thought of those who have left us? I could not really say.

Prism (2007-ongoing)

Video & photo series

[1] 'Ḥilalī also intends to demonstrate the contribution of Izutsu's works to the cumulativeknowledge of Qur'anic scholarship. He wants to explain how the theoretical and practical principles presented by Izutsu 'add scientific and methodological value to the study and the understanding of the Qur'an, unveiling the precision and perspicuity of its verses'. He points out that the principles Izutsu introduced had their precursors in Arabic philology but had only been applied partially and did not allow the study of the overall structure of the Qur'an as a whole. For Ḥilalī, semantics in Izutsu's approach are more comprehensive than familiar sharʿī ('religious') concepts; they aim primarily to identify the nature of conceptual change, and how that has been employed in the Qur'an, bringing about a new worldview.'

[2] The Qur'an, 19.41.

[3] Toshihiko Izutsu, The History of Islamic Thought, (Iwanami Bunko: Tokyo, 1991, p. 18.

[4] Toshihiko Izutsu, Islamic Culture (Iwanami Bunko: Tokyo, 1991), p. 76-80.

TAGSIslam Urbanisation Literature

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Monira Al Qadiri

Monira Al Qadiri is a Kuwaiti visual artist and film maker born in Senegal and educated in Japan.

井筒俊彦

| 画像提供依頼:顔写真の画像提供をお願いします。(2021年1月) |

| 人物情報 | |

|---|---|

| 生誕 | 1914年5月4日 |

| 死没 | 1993年1月7日(78歳没) |

| 国籍 | |

| 出身校 | 慶應義塾大学文学部英文科 |

| 学問 | |

| 研究分野 | 東洋哲学、イスラーム |

| 主な業績 | 神秘主義、サービア教徒 |

| 主な受賞歴 | 朝日賞(1982年) ファーラービー国際賞(2009年) |

井筒 俊彦(いづつ としひこ、1914年(大正3年)5月4日 - 1993年(平成5年)1月7日)は、日本の言語学者、イスラーム学者、東洋思想研究者、神秘主義哲学者。慶應義塾大学名誉教授。文学博士、エラノス会議メンバー、日本学士院会員。語学の天才と称され、大部分の著作が英文で書かれていることもあり、日本国内でよりも、欧米において高く評価されている[1]。

アラビア語、ペルシャ語、サンスクリット語、パーリ語、ロシア語、ギリシャ語等の30以上の言語を流暢に操り、日本で最初の『コーラン』の原典訳を刊行し、ギリシア哲学、ギリシャ神秘主義と言語学の研究に取り組み、イスラムスーフィズム、ヒンドゥー教の不二一元論、大乗仏教(特に禅)、および哲学道教の形而上学と哲学的知恵、後期には仏教思想・老荘思想・朱子学などを視野に収め、禅、密教、ヒンドゥー教、道教、儒教、ギリシア哲学、ユダヤ教、スコラ哲学などを横断する独自の東洋哲学の構築を試みた。

来歴・人物[編集]

東京府出身。父の井筒信太郎はオイルマン。また、書家で、在家の禅修行者。坐禅や公案に親しんで育つ。

旧制青山学院中学で初めてキリスト教に触れる。当初はキリスト教に激しい嫌悪感を抱き、礼拝の最中に嘔吐したこともある[2]。このころ、西脇順三郎のシュルレアリスム文学理論に傾倒。

文学部志望だったが父の反対を受け、1931年4月慶應義塾大学経済学部予科に入学。同級に加藤守雄や池田彌三郎がいた。しかし経済学の講義に興味なく、西脇順三郎教授を慕って、1934年4月、文学部英文科に転じる。在学中、旧約聖書に関心を持ち、神田の夜学で小辻節三からヘブライ語を習う。さらに、夜学の先輩関根正雄と意気投合し、アラビア語の教科書をドイツから取り寄せて、関根と共にアラビア語を学ぶ。同時にロシア語や古典ギリシア語・ラテン語も学習。1度に10の言語を学んだ。ただし「新しい外国語を一つ習得する時は、その国の大使館のスタッフを自宅に下宿させた」という有名な伝説は「生きた人間とはやらない」と自ら否定している[2]。1937年に卒業後、直ちに慶應義塾大学文学部の助手となる。

戦時中は軍部に駆り出されて中近東の要人を相手としたアラビア語の通訳をした。保守思想家でイスラム研究者でもあった大川周明の依頼を受け、満鉄系の東亜経済調査局や回教圏研究所で膨大なアラビア語文献を読破し、イスラーム研究を本格化した。前嶋信次はその時の同僚で、のち共に慶應義塾大教授(東洋史)。1958年に『コーラン』の邦訳を完成させた。井筒訳の『コーラン』は、厳密な言語学的研究を基礎とした秀逸な訳として、現在に至るまで高い評価を受けている。『コーラン』についての意味論的研究『意味の構造』(原著英語)の評価も高く、コーランやイスラーム思想研究では、言語を問わずたびたび引用されている。ちなみに、語学的な才能に富んでいた井筒は、アラビア語を習い始めて1か月で『コーラン』を読破したという。語学能力は天才的と称され30数言語を使いこなしたとも言われる[3]。司馬遼太郎は、対談冒頭で井筒を評し「二十人ぐらいの天才が一人になっている」と語っている[4]。

1959年より、ロシア・フォルマリストのローマン・ヤーコブソンの推薦を得てロックフェラー財団フェローとして、レバノン、エジプト、シリア、ドイツ、パリなど中近東・欧米での研究生活に入る。思想研究の主要な業績はイスラム思想、特にペルシア思想とイスラム神秘主義に関する数多くの著作を出版したことだが、自身は仏教徒で、晩年には研究を仏教哲学(禅、唯識、華厳などの大乗仏典)、老荘思想、朱子学、西洋中世哲学、ユダヤ思想などの分野にまで広げた。古代ギリシア哲学やロシア文学に関する専門書も若くして出版している。東洋思想の「共時的構造化」を試みた『意識と本質』は、井筒の広範な思想研究の成果が盛り込まれた代表的著作とされる。

東洋思想の「共時的構造化」の本格的具現化の試みの第一弾として、1992年に「中央公論」で「東洋哲学覚書 意識の形而上学 『大乗起信論』の哲学」を3回に分け連載したが、翌93年1月7日、就寝中の脳出血により78歳で急逝。遺著として1993年3月に中央公論社で出版。旧蔵書は同大学の記念図書として架蔵され「井筒俊彦文庫目録」[5] が発行(アラビア語・ペルシア語図書/和漢書・洋書部の2冊、2002年)された。

独自の内観法を父親から学び、形而上学的・神秘主義的な原体験を得た。その後、西洋の神秘主義も同じような感覚を記述していることに気付き、古今東西の形而上学・神秘主義の研究に打ち込んだ。世界的に権威ある空前絶後の碩学であり、現代フランスの思想家の一人ジャック・デリダも、井筒を「巨匠」と呼んで尊敬の念を表していた[注 1]。なお夫人の井筒豊子(1925年-2017年4月)は、美学の研究者で英文著作があり国際的に知られている[6]。

中沢新一は河合隼雄との対談で、「井筒はイスラム教から入り仏教やユダヤ教、キリスト教にも何でも深い理解を持ち、宗教の枠組みを超えたメタ宗教の可能性を構想した。その後円熟し、しだいにイスラム教と仏教を同等に捉え「アッラー」は普通言われている「神」ではなく、イスラム教が最も深いところで理解している「アッラー」というのは仏教が言う「真如」と同じだと発言した」と述べている。その後は著書『大乗起信論』で、仏教、イスラム教、ユダヤ教、キリスト教などありとあらゆる宗教が井筒の思考内で合流し、どの宗教も単独では歴史上実現できなかった宗教の夢のようなものを現出させて見せた。仏教は単なる宗教の一つではなく、諸宗教が宗教であることの限界を超えてメタ宗教を目指す過程で必ず仏教のような思想形態があらわれるというのが井筒の思想で、中沢にも強い影響を与える[7]。

一方で、井筒の解釈には個人的な関心に基づくゆえの偏りがみられるという池内恵の指摘がある[8]。

2018年には、彼のドキュメンタリー映画The Eastern(邦訳:シャルギー(東洋人))が公開された[9]。日本では2018年7月24日に公開された[10]。

2019年、NHKドキュメンタリー/BS1スペシャル「イスラムに愛された日本人~知の巨人井筒俊彦~」が制作され、同年11月8日にNHK BS1にて放送された。

職歴[編集]

- 1937年(23歳) - 慶應義塾大学文学部英文学科卒業。

- 1937年(23歳) - 慶應義塾大学文学部助手。

- 1942年(28歳) - 慶應義塾語学研究所研究員兼任[注 2]。

- 同助教授。

- 1954年(40歳) - 慶應義塾大学文学部教授。

- 1959年(45歳) - ロックフェラー財団研究員。

- 1961年(47歳) - カナダ・マギル大学客員教授。

- 1962年(48歳) - 慶應義塾大学言語文化研究所教授。

- 1967年(53歳) - スイス・エラノス会議会員。

- 1969年(55歳) - カナダ・マギル大学イスラーム研究所正教授。

- 1975年(61歳)~1979年(65歳) - イラン王立研究所教授。

- パリ国際哲学研究院正会員。

- 1981年(67歳) - 慶應義塾大学名誉教授。

- 1982年(68歳) - 日本学士院会員。

賞歴[編集]

- 1949年(35歳) - 『神秘哲学』第一回福澤賞・義塾賞。

- 1982年(68歳) - 『イスラーム文化――その根底にあるもの』 毎日出版文化賞。

- 1982年(68歳) - 朝日賞。

- 1984年(70歳) - 『意識と本質――精神的東洋を索めて』 読売文学賞(研究・翻訳部門)。

- 2009年(故人) - ファーラービー国際賞(故人部門)

著書[編集]

- 『アラビア思想史―回教神學と回教哲學』(博文館〈興亜全書〉、1941年)

- 『神秘哲學―ギリシアの部』(哲学修道院〈世界哲學講座〉、1949年)

- 『アラビア語入門』(慶應出版社、1950年)

- 『マホメット』(弘文堂〈アテネ文庫〉、1952年/講談社学術文庫、1989年)

- 『ロシア的人間―近代ロシア文学史』(弘文堂、1953年/北洋社、1978年/中公文庫、1989年)

- 『神秘哲学 第1部―自然神秘主義とギリシア』(人文書院、1978年)

- 『神秘哲学 第2部―神秘主義のギリシア哲学的展開』(人文書院、1978年)

- 『イスラーム生誕』(人文書院、1979年/中公文庫、1990年、改版2003年)

- 『イスラーム哲学の原像』(岩波新書、1980年、復刊1998年、2013年)[注 3]

- 『イスラーム文化―その根底にあるもの』(岩波書店、1981年/岩波文庫、1991年、ワイド版1994年)

- 『イスラーム思想史―神学・神秘主義・哲学』(岩波書店、1982年/中公文庫、1991年、新版2005年、改版2009年)

- 『コーランを読む』(岩波書店〈岩波セミナーブックス〉、1983年/岩波現代文庫、2013年2月、若松英輔解説)

- 『意識と本質―精神的東洋を索めて』(岩波書店、1983年/岩波文庫、1991年、ワイド版2001年)

- 独訳版 Bewusstsein und Wesen, Hans Peter Liederbach, Iudicium Verlag, München, 2006

- 『意味の深みへ―東洋哲学の水位』(岩波書店、1985年、復刊2013年/岩波文庫、2019年3月、斎藤慶典解説)

- 『コスモスとアンチコスモス―東洋哲学のために』(岩波書店、1989年、復刊2005年/岩波文庫、2019年5月、河合俊雄解説)

- 『超越のことば―イスラーム・ユダヤ哲学における神と人』(岩波書店、1991年、復刊2004年)

- 『意識の形而上学―「大乗起信論」の哲学』(中央公論社、1993年/中公文庫、2001年)

- 『読むと書く 井筒俊彦エッセイ集』(慶應義塾大学出版会、2009年、若松英輔編)[注 4]

- 『神秘哲学―ギリシアの部』(慶應義塾大学出版会、2010年、若松英輔校訂・解説/岩波文庫、2019年2月、竹下政孝・山内志朗校訂、納富信留解説)

- 『アラビア哲学―回教哲学』(慶應義塾大学出版会、2011年、若松英輔校訂)[注 5]

- 『露西亜文学』(慶應義塾大学出版会、2011年、若松英輔校訂、亀山郁夫解説)

英文著作[編集]

- 老子 Lao-Tzu The way and its virtue

- 〈The Izutu library series on Oriental philosophy〉(慶應義塾大学出版会 2001年)

- The Structure of Oriental Philosophy Collected Papers of the Eranos Conference(全4巻)

- 〈The Izutu Library Series on Oriental Philosophy〉(慶應義塾大学出版会 2008年)

- God and Man in the Koran Semantics of the Koranic Weltanschauung

- 〈The Izutu Library Series on Oriental Philosophy〉(慶應義塾大学出版会 2015年)

- The Concept of Belief in Islamic Theology

- 〈The Izutu Library Series on Oriental Philosophy〉(慶應義塾大学出版会 2016年)

英文著作(訳書)[編集]

- 『意味の構造―コーランにおける宗教道徳概念の分析』(新泉社、1972年、牧野信也訳)

- 『禅仏教の哲学に向けて』(ぷねうま舎、2014年、新版2019年、野平宗弘訳注、頼住光子解説)

- 『井筒俊彦英文著作翻訳コレクション』(全7巻(全8冊)、慶應義塾大学出版会)

- 『老子道徳経』(古勝隆一訳、2017年4月)

- 『クルアーンにおける神と人間―クルアーンの世界観の意味論』(鎌田繁監訳、仁子寿晴訳、2017年6月)

- 『存在の概念と実在性』(鎌田繁監訳、仁子寿晴訳、2017年10月)

- 『言語と呪術』(安藤礼二監訳、小野純一訳、2018年9月)

- 『イスラーム神学における信の構造―イーマーンとイスラームの意味論的分析』(鎌田繁監訳、仁子寿晴・橋爪烈訳、2018年2月)

- 『東洋哲学の構造―エラノス会議講演集』(澤井義次監訳、金子奈央・古勝隆一・西村玲訳、2019年3月)

- 『スーフィズムと老荘思想―比較哲学試論』(上・下、仁子寿晴訳、2019年6月)

翻訳[編集]

- 『コーラン』(岩波文庫(上中下)、1957-58年、改版1964年、新版2009年/ワイド版2004年)

- マルティン・C・ダーシー『愛のロゴスとパトス』(三辺文子共訳、創文社、1957年)

- ジャラール・ルーミー『ルーミー語録』(イスラーム古典叢書:岩波書店、1978年)

- モッラー・サドラー『存在認識の道 存在と本質について』(イスラーム古典叢書:岩波書店、1978年[注 6])

全集[編集]

- 井筒俊彦著作集(全11巻・別巻、中央公論社、1991年-1993年)

- 神秘哲学

- イスラーム文化

- ロシア的人間

- 意味の構造 コーランにおける宗教道徳概念の分析(牧野信也訳)

- イスラーム哲学

- 意識と本質 東洋的思惟の構造的整合性を索めて

- コーラン(翻訳)

- コーランを読む

- 東洋哲学

- 存在認識の道 存在と本質について(モッラー・サドラー、井筒訳・解説)

- ルーミー語録(ジャラール・ルーミー、井筒訳・解説)

- 別巻 対談鼎談集・著作目録

- 井筒俊彦全集(全12巻・別巻、慶應義塾大学出版会、2013年-2016年)[11]

- アラビア哲学 1935年-1948年

- 神秘哲学 1949年-1951年

- ロシア的人間 1951年-1953年

- イスラーム思想史 1954年-1975年

- 存在顕現の形而上学 1978年-1980年

- 意識と本質 1980年-1981年

- イスラーム文化 1981年-1983年

- 意味の深みへ 1983年-1985年

- コスモスとアンチコスモス 1985年-1989年

- 意識の形而上学 1988年-1993年

- 意味の構造 1992年

- アラビア語入門(横組み)

- 別巻 補遺・目録・年譜・索引(付・講演音声CD)

対談・伝記・研究[編集]

- 『叡知の台座 井筒俊彦対談集』(岩波書店、1986年)

- 若松英輔 『井筒俊彦 叡知の哲学』(慶應義塾大学出版会、2011年5月)[注 7]

- 若松英輔 『叡知の詩学 小林秀雄と井筒俊彦』(慶應義塾大学出版会、2015年10月)[注 8]

- 井筒豊子 『井筒俊彦の学問遍路 同行二人半』(慶應義塾大学出版会、2017年9月)[注 9]

- 『井筒俊彦とイスラーム 回想と書評』(松原秀一・坂本勉編、慶應義塾大学出版会、2012年10月)

- 『井筒俊彦 言語の根源と哲学の発生』(河出書房新社【KAWADE道の手帖】、2014年6月、増補版2017年6月)[注 10]

- 『井筒俊彦の東洋哲学』(澤井義次・鎌田繁編、慶應義塾大学出版会、2018年9月)[注 11]

- 『井筒俊彦ざんまい』(若松英輔編、慶應義塾大学出版会、2019年10月)

- 斎藤慶典『「東洋」哲学の根本問題 あるいは井筒俊彦』(講談社選書メチエ、2018年2月)

- バフマン・ザキプール『井筒俊彦の比較哲学』(知泉書館、2019年2月)

- 西平直『井筒俊彦と二重の見 東洋哲学序説』(未来哲学研究所、2021年)

英文記念論集[編集]

- 『Consciousness and Reality――Studies in Memory of Toshihiko Izutsu』(松原秀一ほか編、岩波書店、1998年2月)[注 12]

映像[編集]

- 『シャルギー(東洋人)』 - イラン制作、2018年。井筒の生涯と思想を紹介するドキュメンタリー映画。監督マスウード・ターヘリー、日本語字幕[12]。

- NHK BS1スペシャル『イスラムに愛された日本人 知の巨人・井筒俊彦』、2019年11月8日。案内人サヘル・ローズ

関連人物[編集]

- 鈴木大拙(仏教・哲学)

- 折口信夫(大学時代に受講)

- 上田閑照(東洋哲学・エックハルト研究)

- 河合隼雄(ユング心理学)

- 今道友信(哲学)

- 大川周明(満鉄)

- 前嶋信次(イスラーム学)

- 黒田壽郎(イスラーム学)

- 牧野信也(イスラーム学)

- 中村廣治郎(イスラーム学)

- 五十嵐一(イスラーム学)

- 深田甫(ドイツ文学)

- 鈴木孝夫(言語社会学)

- 柏木英彦(中世哲学)

- 丸山圭三郎(言語学)

- カール・グスタフ・ユング(深層心理学)

- ルドルフ・オットー(宗教学)

- アンドレアス・シュパイザー(数学)

- アンリ・コルバン(イスラム神秘主義)

- ゲルショム・ショーレム(ユダヤ神秘主義)

- ルイ・マシニョン(オリエント学)

- フーゴー・ラーナー(教会史)

- ハインリヒ・ツィンマー(インド学)

- ミルチャ・エリアーデ(宗教学)

- エーリヒ・ノイマン(精神医学・神話学)

- エルンスト・ベンツ(東方教会史・神秘主義)

- カール・ケレーニイ(神話学・古典文献学)

- ジル・クィスペル(グノーシス学)

- アドルフ・ポルトマン(生物学)

- パウル・ティリッヒ(組織神学)

- ファン・デル・レーウ(宗教現象学)

- マルティン・ブーバー(宗教哲学)

- カール・レーヴィト(哲学)

- ムーサー・ビギエフ(イスラーム学)

脚注[編集]

注釈[編集]

- ^ 著作集刊行に際して、牧野信也の紹介の一節。

- ^ 西脇順三郎、松本信広、辻直四郎、服部四郎、福原麟太郎、市河三喜らが同僚。

- ^ 「超越のことば」に再収録。

- ^ 著作集未収録の文章を集成。

- ^ 解題・鎌田繁(東京大学東洋文化研究所教授)、「アラビア哲學」(光の書房、1948年)を復刻。他に「東印度に於ける回教法則(概説)」(東亜研究所、1942年)を収録。各・初版を、新字新かなに改めた版。

- ^ イスラーム哲学におけるタウヒード(価値観)の原典。

- ^ 全10章の評伝。2009-2010年に「季刊 三田文学」に『井筒俊彦 存在とコトバの神秘哲学』を全6回連載。書き下ろしを加えた。

- ^ 「三田文学」に一部連載。

- ^ 豊子夫人(1925年-2017年4月)の回想記。澤井義次編・解説。

- ^ 若松英輔・安藤礼二責任編集。対談、高橋巌、末木文美士、中沢新一、鎌田東二、山城むつみ、吉村萬壱ほかが寄稿。

- ^ 13名の論考集。

- ^ 26名による追悼論集。

出典[編集]

- ^ “思想家紹介 井筒俊彦”. 京都大学大学院文学研究科・文学部. 2019年4月21日閲覧。

- ^ a b 安岡章太郎ほか「思想と芸術」『安岡章太郎15の対話』新潮社、1997年。ISBN 4103219084。

- ^ 牧野信也「井筒俊彦」『哲学がわかる』蜷川真夫ほか、朝日新聞社〈Aera mook〉、1995年。

- ^ 司馬遼太郎ほか「二十世紀末の闇と光」『司馬遼太郎歴史歓談』中央公論新社、2000年。ISBN 4120030695。

- ^ 平尾行藏「慶應義塾図書館編・刊『井筒俊彦文庫目録』 (PDF) 」 『MediaNet No.11』、慶應義塾大学メディアセンター、2004年10月。

- ^ 井筒豊子名で出版した日本語文献は、訳書『アラビア文学史』(ハミルトン・ギブ、人文書院、のち「アラビア人文学」講談社学術文庫)、『さまよう ポストモダンの非/神学』(マーク・テイラー、岩波書店)や、小説『白磁盒子』(中公文庫)がある。

- ^ 河合隼雄、中沢新一『仏教が好き!』朝日新聞出版〈朝日文庫〉、2008年6月30日。ISBN 9784022615688。[要ページ番号]

- ^ 池内恵「井筒俊彦の主要著作に見る日本的イスラーム理解」『日本研究』第36巻、国際日本文化研究センター、2007年9月。[要ページ番号]

- ^ “Documentary on Life of Japanese Qur’an Scholar”. 2018年7月27日閲覧。

- ^ “日本で、井筒俊彦氏関連のドキュメンタリー映画「東洋人」(シャルギー)が公開”. 2018年7月27日閲覧。

- ^ “「井筒俊彦全集」 特設サイト「井筒俊彦」~言語学者、イスラーム学者、東洋思想研究者、神秘主義哲学者”. 慶應義塾大学出版会. 2019年3月13日閲覧。

- ^ “ドキュメンタリーが示す新たな井筒俊彦とその可能性”. neoneo web(2018年9月1日). 2018年9月1日閲覧。

外部リンク[編集]

- 『三田文学No.96.特集井筒俊彦』(2009年冬季号) - 三田文學

- 「井筒俊彦入門」(若松英輔) - 慶應義塾大学出版会

- 思想家紹介 井筒俊彦 - 京都大学大学院文学研究科日本哲学史研究室

- 「井筒俊彦全集」 - 慶應義塾大学出版会

- 吉田悠樹彦 「ドキュメンタリーが示す新たな井筒俊彦とその可能性」 - neoneo web

Toshihiko Izutsu

Toshihiko Izutsu (井筒 俊彦, Izutsu Toshihiko, 4 May 1914 – 7 January 1993) was a Japanese philosopher of language and mysticism and an Islamic scholar.[1][2] He was a Professor at Keio University in Japan and author of many books on Islam and other religions. Izutsu taught at the Institute of Cultural and Linguistic studies at Keio University in Tokyo, the Iranian institute of Philosophy in Tehran, and McGill University in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. He was fluent in over 30 languages, including Arabic, Persian, Sanskrit, Pali, Chinese, Japanese, Russian and Greek.

Life and academic career[edit]

He was born on 4 May 1914 in a wealthy family in Tokyo, Japan. From an early age, he was familiar with zen meditation and kōan, since his father was also a calligrapher and a practising lay Zen Buddhist.

He entered the faculty of economics at Keio University, but transferred to the department of English literature wishing to be instructed by Professor Junzaburō Nishiwaki. Following his bachelor's degree, he became a research assistant in 1937.

In 1958, he completed the first direct translation of the Qur'an from Arabic to Japanese. (The first indirect translation had been accomplished a decade prior by Okawa Shumei.) His translation is still renowned for its linguistic accuracy and widely used for scholarly works. He was extremely talented in learning foreign languages, and finished reading the Qur'an a month after beginning to learn Arabic. Between 1969-75, he became professor of Islamic philosophy at McGill University in Montreal. He was the professor of philosophy in the Iranian institute in philosophy, formerly Imperial Iranian Academy of Philosophy, in Tehran, Iran. He came back to Japan from Iran after the Revolution in 1979, and he wrote, seemingly more assiduously, many books and articles in Japanese on Oriental thought and its significance.

In understanding Izutsu's academic legacy, there are four points to bear in mind: his relation to Buddhism, particularly Zen Buddhism, his interest in language, his inclination towards postmodernism, and his interest in comparative philosophy.[3]

In Sufism and Taoism: A comparative study of key philosophical concepts (1984), he compares the metaphysical and mystical thought-systems of Sufism and Taoism and discovers that, although historically unrelated, the two share features and patterns.[3]

Bibliography[edit]

- Language and Magic, Studies in the Magical Function of Speech, Keio University 1956

- Ethico-Religious Concepts in the Quran (1966 republished 2002) ISBN 0-7735-2427-4

- The Concept and Reality of Existence (1971) ISBN 9839154818

- Concept of Belief in Islamic Theology (1980) ISBN 0-8369-9261-X

- God and Man in the Koran (1980) ISBN 0-8369-9262-8

- Sufism and Taoism: A Comparative Study of Key Philosophical Concepts (1984) ISBN 0-520-05264-1

- Creation and the Timeless Order of Things: Essays in Islamic Mystical Philosophy (1994) ISBN 1-883991-04-8

- Toward a Philosophy of Zen Buddhism (2001) ISBN 1-57062-698-7

- Language and Magic - Studies in the Magical Function of Speech (1956) Keit Institute of Philological Studies

- The Metaphysics of Sabzvârî, tr. from the Arabic by Mehdi Mohagheg and Toshihiko Izutso, Delmar, New York, 1977.

- Mollā Hādī Sabzavārī’s Šarḥ ḡorar al-farāʾed, maʿrūf be-manẓūma-ye ḥekmat, qesmat-e omūr-e ʿāmma wa ǰawhar wa ʿaraż, ed. and annotated by Mahdī Moḥaqqeq and Toshihico Izutso, Tehran, 1348 Š./1969

References[edit]

- ^ Masataka, Takeshita (2016). "Toshihiko Izutsu's contribution to Islamic Studies". Journal of International Philosophy. 7 (special): 78–81. doi:10.34428/00008151.

- ^ Al-Daghistani, Sami (2018). "The Time Factor – Toshihiko Izutsu and Islamic Economic Tradition". Asian Studies. 6 (1): 55–71. doi:10.4312/as.2018.6.1.55-71.

- ^ a b Kojiro Nakamura (November 2009). "The Significance of Toshihiko Izutsu's Legacy for Comparative Religion". Intellectual Discourse. 17 (2): 14–158.

- ^ "Toshihiko Izutsu's life and work".