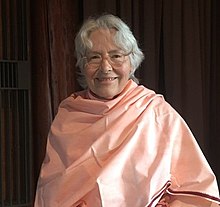

Pravrajika Vrajaprana

Pravrajika Vrajaprana | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1952 (age 71–72) California, U.S. |

| Occupation(s) | Pravrajika (or sannyasini) at Vedanta Society of Southern California, Writer |

| Known for | Writer on Vedanta, Swami Vivekananda, Ramakrishna, Christopher Isherwood. |

Pravrajika Vrajaprana (born 1952) is a sannyasini or pravrajika (female swami) at the Vedanta Society of Southern California, affiliated with the Ramakrishna Order. She resides at Sarada Convent in Santa Barbara, California[1][2][3] and a writer on Vedanta, the history and growth of the Vedanta Societies.[4][5]

She is also a well known speaker and scholar on Hinduism and she speaks frequently at colleges, universities and interfaith gatherings and is the Hindu chaplain at Cottage Hospital in Santa Barbara.[6] Her works on Vedanta include, Vedanta: A Simple Introduction (1999), editor of Living Wisdom (1994). She is the co-author, with Swami Tyagananda, of Interpreting Ramakrishna: Kali's Child Revisited (2010).[7]

Pravrajika Vrajaprana was born in California in 1952. She graduated from the University of California, Santa Cruz, where she also worked briefly as Associate Professor of Literature.[8] She came in contact with Swami Prabhavananda at the Vedanta Society of Santa Barbara in 1967, while involved with anti-Vietnam war activism.[2] In 1977 she joined the Sarada Convent in Santa Barbara.[1] She took the first vows of brahmacharya in 1983 and had final vows of sannyasa in 1988.[8]

Vrajaprana was a co-speaker with the 14th Dalai Lama at the Interfaith Conference in San Francisco (2006).[9] She was a panelist in the discussion on Interpreting Ramakrishna at DANAM, held at the annual AAR meeting 2010.[10][11]

Selected works[edit]

- My Faithful Goodwin. Calcutta: Advaita Ashrama, 1994. ISBN 81-85301-25-5. [Biography of J.J. Goodwin, disciple of Swami Vivekananda.]

- Seeing God Everywhere (editor). Hollywood: Vedanta Press, 1996.

- Living Wisdom: Vedanta in the West, (editor). Hollywood: Vedanta Press, 1994. “A Meaningful Life,” 58–62.

- A Portrait of Sister Christine. Calcutta: Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture, 1996. ISBN 81-85843-80-5.

- Vedanta: A Simple Introduction. Hollywood: Vedanta Press, 1999.

- Review of Kali’s Child: The Mystical and the Erotic in the Life of Ramakrishna. In Hindu-Christian Studies Bulletin, 10, (1997).

- "Contemporary Spirituality and the Thinning of the Sacred: A Hindu Perspective." Cross Currents (Spring/Summer 2000) 248–256.

- "Regaining the Lost Kingdom: Purity and Meditation in the Hindu Spiritual Tradition." In Purity of Heart and Contemplation: A Monastic Dialogue Between Christian and Asian Traditions, ed. Bruno Barnhart and Joseph Wong. New York: Continuum, December, 2001, pp. 23–38.

- "The Convert—Stranger in Our Midst: Crossing Borders in Two Worlds." In The Stranger’s Religion: Fascination and Fear, ed. Anna Lännström. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2004, pp. 169–185.

- "Looking In and Letting Go: Viveka and Vairâgya in the Vedanta Tradition." In Asceticism, Identity and Pedagogy in Dharma Traditions, ed. Graham M. Schweig, Jeffery D. Long, Ramdas Lamb, Adarsh Deepak. Hampton, VA: Deepak Heritage Books. 2006, pp. 33–48.

- "The Guru and His Queer Disciple: The Guru-Disciple Relationship as the Locus of Christopher Isherwood’s Advaita Vedanta." Postscripts: The Journal of Sacred Texts & Contemporary Worlds (November 2010) 243–258.

- Interpreting Ramakrishna: Kali's Child Revisited, co-authored with Swami Tyagananda. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 2010.

- "Interfaith Incognito or What a Hindu Nun Learned from Christian Evangelicals" in My Neighbor's Faith: Stories of Interreligious Encounter, Growth, and Transformation, ed. Rabbi Or Rose and Jennifer Peace. New York: Orbis Books, 2012, pp. 20–24.

- “Perfect Independence”: Vivekananda, Freedom, and Women in Swami Vivekananda: His Life, Legacy, and Liberative Ethics, ed. Rita D. Sharma. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2021, pp. 145–158.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Bardach, Ann Louise (April 2010). "Shangri-La". LA Yoga Magazine. 9 (3). Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ a b Philip Goldberg (2010). American Veda. Crown Publishing. pp. 84–85.

- ^ Bucknell, Katherine (2010). The Sixties: Diaries:1960-1969. HarperCollins. pp. xl.

- ^ Eugene V. Gallagher, W. Michael Ashcraft (2006). Introduction to New and Alternative Religions in America. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 10. ISBN 9780275987176.

- ^ Beckerlegge, Gwilym (2004). "The Early Spread of Vedanta Societies: An Example of "Imported Localism"". Numen. Brill Publishers. 51 (3): 301. doi:10.1163/1568527041945526. JSTOR 3270585.

- ^ The Religion in the United States: Pluralism and Public Presence 2012 Archived 2012-07-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Philip Goldberg (2010). American Veda. Crown Publishing. p. 357.

- ^ a b Anna Lännström (2004). Stranger's Religion. University of Notre Dame Press. p. xvii.

- ^ Kim Vo (April 16, 2006). "Dalai Lama promotes harmony of religions". Mercury News. Retrieved 2011-03-12.

- ^ "Panel discussion on Interpreting Ramakrishna" (PDF). Dharma Academy of North America (DANAM). Retrieved 2011-02-01.

- ^ Pedersen, Kusumita P. (March 2011), "Book Reviews : Interpreting Ramakrishna", Hinduism Today: 57, retrieved 3 March 2011

External links[edit]

THE BLOG INTERFAITH DIALOGUECHRISTIANITYINTERFAITH

Interfaith Incognito: What a Hindu Nun Learned From an Evangelical Christian

Having been in the back-patting position often enough myself, I propose that what works most effectively is interfaith dialogue that is not initiated for the sake of public consumption. It is spontaneous, unrehearsed and often completely unexpected.

By Pravrajika Vrajaprana, Contributor

Hindu Nun

May 24, 2012, 12:25 PM EDT

Updated Jul 15, 2012

This post was published on the now-closed HuffPost Contributor platform. Contributors control their own work and posted freely to our site. If you need to flag this entry as abusive, send us an email.

===

While I have attended any number of interfaith events and have found them an interesting, even engrossing, experience, one could argue that these gatherings have limited value. I say this not from any lack of respect for interfaith dialogue. Indeed, the monastic order to which I belong, the Ramakrishna Order of India (whose Western branches are known as Vedanta Societies), has long been in the forefront of inter-religious dialogue. Ramakrishna, a Hindu saint of 19th-century India, practiced not only the various spiritual disciplines within the Hindu tradition, he also practiced spiritual disciplines in the Islamic and Christian traditions. He achieved mystic union with the divine by following each path, and thus it was from his own experience that he taught that every religion is a valid and true entryway to the ultimate Reality. That Reality is called by various names since it seen through different lenses, interpreted through various minds, and refracted through various cultures, but that one Reality is the same.

This outlook gained greater currency when Ramakrishna's disciple Swami Vivekananda spoke as the Hindu representative at the World's Parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1893. The Parliament was the first genuinely representative interfaith event in Western history. Vivekananda's appearance there also marked the first real introduction of Hinduism to the Western world. In his address, presciently delivered on Sept. 11, 1893, Vivekananda noted that he was "proud to belong to a religion which has taught the world both tolerance and universal acceptance. We believe not only in universal toleration, but we accept all religions as true." He concluded: "I fervently hope that the bell that tolled this morning in honor of this convention may be the death-knell of all fanaticism, of all persecutions with the sword or with the pen, and of all uncharitable feelings between persons wending their way to the same goal."

ADVERTISEMENT

One hundred and eight years later in New York City, the significance of Vivekananda's words became more poignant than ever. Given that, why would I suggest that the importance of interfaith gatherings is overstated? One reason is that the learning that occurs in these gatherings typically flows in one direction: I speak; you listen. Then, you speak; I listen. There is no two-way traffic here, thus the knowledge that is gained, while worthy, tends to be superficial.

The deeper, more intractable problem is that those of us who attend these gatherings are those most likely to be open-minded about other religious traditions in the first place. Preaching to the choir can be a satisfying experience because we all enjoy getting positive feedback: we all get to agree, we can all get along, we pat each other on the back and we feel good about ourselves and our enlightened motives. But I do not think that these kinds of gatherings are the best way to fundamentally change anyone -- let alone the world.

Having been in the back-patting position often enough myself, I would propose that what works more effectively as far as genuine inter-religious dialogue is what I call "interfaith incognito." By this I mean interfaith dialogue that is not initiated for the sake of public consumption. It is spontaneous, unrehearsed and often completely unexpected. These kind of encounters -- chanced upon without our official garb, without our sonorous voices chanting Sanskrit chants or Quranic surahs or Psalms of David, without our made-for-the-public explanation of our traditions -- can be much more genuine, contain much more truth and can be much more transformative. There are no speeches, just real human interaction. This kind of genuine two-way traffic can effect change, but the change is quiet, incremental and without fanfare. We are not dealing with auditoriums of hundreds or thousands of people, we are addressing one human being at a time and we are also being changed as we change others who encounter us.

I may be the only Hindu nun in the world who is also an enthusiastic choral singer. I love my Sanskrit chants but I also love my Bach B-Minor Mass. I've sung in a choral group for more than 15 years and it was during a choral rehearsal that an incognito interfaith event took place. Every rehearsal during break, I have a cup of Lemon Lift tea. One of our baritones, a kindly looking gentleman by the name of Will, liked the same tea and after some time, he began saving me a teabag, knowing I'd be looking for that vocal-clearing brew. One evening as we were sipping tea, Will said: "You know, I've been singing with you so long, but I have no idea what you do for a living." The question made me smile because I knew he would be surprised by my response. I have never attended a rehearsal in the official saffron colors of my monastic order. I wore jeans and pullovers like everyone else.

In response to Will's question I said: "Of all the people in this choir, I am the one with the strangest occupation." A soft-spoken and careful man, Will said, "No, I can't believe that! What do you do?" OK, I thought, I might as well go for it. "Will, I'm a Hindu nun." I saw the color drain from his face. "You're a what?" "A Hindu nun." "I didn't know there was such a thing." He was clearly perturbed. "Yes, not only is there such a thing, I am one." He stared at me in disbelief. I reached for a tenor walking by, one who had visited our temple: "Denny, am I a Hindu nun?" "Yeah, she's a Hindu nun all right!" Looking at me seriously, Will said: "I'm in Campus Crusade for Christ. I go to India every year and do free heart surgeries."

Now I was the one who was taken aback. Will wasn't the only one with something to learn. "Will," I said, "I'm so happy to learn that. The monastic order to which I belong, the Ramakrishna Order of India, is one of India's largest social service organizations. We have many hospitals and educational facilities -- from pre-school to university level. We have schools for the blind and for the physically and mentally disabled. We do relief and rehabilitation work for victims of famine, flood, epidemics and communal disturbances. We believe that in serving humanity we are worshipping God in the same way that we worship God in the temple."

Will listened gravely then finally said: "I see that I need to learn more about your religion." The truth is, I could have said the same thing myself, although I knew well the tenets of popular Christianity. Will listened with complete attention to every word I said. You can always tell when someone isn't listening to what you say; they may be looking at you with glazed eyes, but their minds are preoccupied as they prepare their counter-response. Will was not doing that. To my surprise, he did not attempt to dissuade me from my tradition nor did he speak slightingly of it. His humility, his humane and respectful response, his willingness to listen and learn instead of preach, taught me more than I taught him. I had attended many an interfaith gathering with Christians, but no one spoke more powerfully to his faith than Will.

And, truth be told, if I had known that Will belonged to Campus Crusade for Christ before we had shared that cup of Lemon Lift tea, I doubt that I would have looked forward to a conversation with him. If he had negative preconceptions about Hinduism, I have to admit that I also had plenty of misconceptions -- and prejudices -- about evangelical Christians. It is shameful to be involved in inter-religious dialogue and still expect narrow-mindedness in others when, in fact, it is lodged in oneself. Had my own unexamined prejudices not unexpectedly been put under the light of Will's open-hearted response, I wouldn't have known they were there.

Was Will's reaction a cosmetic response? Was he merely being polite? Nothing indicates that. We spoke more often during breaks; he was always there, saving me a teabag. His kindness, his goodness, his unselfish character came through whatever he did and said, no matter what or who he was discussing.

A cardiologist, Will developed serious heart problems himself and illness compelled him to leave the choir. After some months elapsed, he called to see how I was doing. I told him that I was praying for him and he was genuinely grateful -- just as I was grateful when he told me that I was included in his prayers. In our telephone conversations today he thanks me for my prayers. I have been on various interfaith panels with high-profile Christians, but no one has broadened my mind more than Will, no one has made me appreciate Christianity more and no one else has given me a sense of how transformative evangelical Christianity can be. And for that, I can only be grateful.

Not everyone is interested in inter-religious events. By and large the world is populated by people who either don't care whose beliefs allow no place for interfaith dialogue -- attitudes we can find in every one of our faith traditions. How we reach them is our challenge. How we change ourselves and remove our own unexamined prejudices is also the challenge. Interfaith gatherings lack the means to solve these challenges. They, like wrongly prescribed drugs, often serve to mask the symptoms without curing the illness. For after our gatherings have ended, our goodbyes have been said and the kumbaya moments have dissipated, what has changed?

The only way to genuinely effect change -- change in ourselves and change in others -- is to be what each of our religions tells us that we should be. To be a Hindu in the best way possible is to be a human being in the best way possible. It works with every faith tradition. By being our religion we do much more for interfaith work than all the speeches we've ever made put together. Do it, and make it a lifetime commitment. And try doing it incognito. You may be surprised by what you discover.

This column is an excerpt from 'My Neighbor's Faith: Stories of Interreligious Encounter, Growth, and Transformation.'

The Stakes Have Never Been Higher

As the 2024 presidential race heats up, the very foundations of our democracy are at stake. At HuffPost, we believe that a vibrant democracy is impossible without well-informed citizens. This is why we keep our journalism free for everyone, even as most other newsrooms have retreated behind expensive paywalls.

Our newsroom continues to bring you hard-hitting investigations, well-researched analysis and timely takes on one of the most consequential elections in recent history. Reporting on the current political climate is a responsibility we do not take lightly — and we need your help.