베단타 학파

| 힌두교 |

|---|

베단타 학파(वेदान्त, Vedānta)는 베다의 지식부(知識部)의 근본적인 뜻, 즉 아란야카와 우파니샤드의 철학적 · 신비적 · 밀교적 가르침을 연구하는 힌두교 철학 학파로 힌두교의 정통 육파철학 중 하나이다.[1] 우타라(後) 미맘사 학파라고도 불린다.

힌두 철학에서 원래 베단타(Vedānta)라는 단어는 베다 중 우파니샤드와 동의어로 사용되었다. 베단타라는 단어는 "베다-안타(Veda-anta)" 즉 "베다의 끝" 또는 "베다 찬가에 더해진 부록"의 뜻인데, 이 뜻이 심화되어 "베다의 목적, 목표 또는 최종 도달지"를 의미하는 것으로도 여겨지고 있다.[2] 베단타는 또한 삼히타, 즉 네 종의 베다를 모두 마스터한 사람을 가리키는 일반 명사로도 사용된다. 8세기에 이르러서는 "베단타"라는 단어는 아트마 즈냐나(자아 실현), 즉 우주의 궁극적 실재(브라만)를 아는 것을 중심 주제로 하는 특정 힌두 철학 그룹을 지칭하는 용도로 사용하게 되었다.

베단타 학파의 개조(開祖)는 바다라야나(1세기)라고도 하나 그의 전기(傳記)는 분명치 않다. 경전(經典)으로는 《베단타 수트라》(4~5세기, 브라마 수트라라고도 한다)가 있으나 극단적으로 간결하기 때문에 주석 없이는 이해할 수가 없어서 많은 사람이 주석을 하기에 이르렀다. 그 주석의 차이로부터 분파가 생겨남으로써 베단타 철학의 발달을 촉진하였으며 그 결과 베단파 학파는 힌두교의 육파 철학 중에서 가장 유력한 학파가 되었다. 《베단타 수트라》의 주석서로서 가장 유명한 것은 아드바이타 베단타 학파의 창시자인 샹카라(8세기경)의 주석서이다.

다른 이름[편집]

베단타 학파는 우타라(後) 미맘사라고도 불리는데, 이것은 베다의 제사부(祭事部)[3], 즉 삼히타(Samhitas)와 브라마나(Brahmanas)를 연구하는 학문을 카르마 미맘사 또는 푸르바(前) 미맘사라고 부르는 것과 대비하여 부르는 호칭으로, 베다의 지식부(知識部), 즉 아란야카(Āraṇyakas)와 우파니샤드(Upanishads)의 근본적인 뜻과 가르침을 연구하는 철학 그룹을 지칭하는 말인데, 이 그룹이 시대 순으로 후대에 나왔다는 의미와 더 뛰어난 가르침이라는 의미를 둘 다 가지는 말이다.[1] "미맘사(Mimamsa)"는 숙려 · 조사 · 연구의 뜻으로 영어로는 주로 "enquiry"라고 번역된다. 우타라 미맘사는 "후대의 연구" 또는 "더 뛰어난 연구"의 뜻이며 푸르바 미맘사는 "전대의 연구"의 뜻이다.

사상[편집]

우파니샤드의 중시[편집]

사상적으로는 베단타 학파는 베다 성전 가운데에서 특히 우파니샤드를 중요시하였는데, 우파니샤드의 여러 현자들 중에서도 우다라카(Uddalaka)의 사상을 중심으로 하여 베다와 우파니샤드의 여러 사상을 조화시키고 통일을 꾀했다.[1]

예를 들어, 삼키아 학파의 푸루샤(우주적 영 · Cosmic Spirit)과 프라크리티(우주적 질료 · Cosmic Substance)의 2원론을 부정하고, 절대자 브라만은 프라크리티와 같은 질료적인 것이 아니라 순수한 영적 실재이며 영구불멸의 존재인 동시에 세계를 창조하는 제1 원인(First Cause)이라고 하였다.[1]

또한, 베단타 학파에서는, 개인아(個人我)인 아트만은 우주의 궁극적 실재인 브라만의 일부분이며, 우주적인 존재인 브라만에 비교하면 원자(原子)만한 크기에 불과하지만 브라만과 다른 존재가 아니라고 하였다.[1] 무시(無始) 이래 윤회를 반복하고 있는 개인아는 브라만을 명상(冥想)함으로써 아트마 즈냐나(Atma Jnana · 명지 · 明知) 또는 비드야(Vidya)를 얻을 때 브라만과의 합일을 이루어 해탈하게 된다고 하였다.[1] 이 아트마 즈냐나에 도달하는 수단으로써 우파니샤드의 가르침을 중시하였다.[1]

불이일원론

베단타 학파의 가르침에 따르면, 유일절대의 브라만만이 참된 실재인데 개인아인 아트만은 자신의 진정한 본성을 직관(直觀)하게 될 때 그 즉시로 최고아(最高我)인 브라만과 완전히 동일해진다.[1] 베단타 학파는 이러한 절대적 일원론적 존재 모습이 우주의 진실된 모습이며, 현상계의 다양성은 마야(환영 · 幻影)로서 실체가 없는 것이라고 본다.[1]

따라서 베단타 학파에서는 무지(無知 · Avidyā · Ignorance) · 무명(無明 · Avidyā) 또는 망상(妄想 · Avidyā · Delusion)이란 아트만과 브라만이 분리되어 있다는 앎(인식 · 지식)이라고 본다. 그리고 이것은 곧 신(브라만)을 알지 못하는 상태와 동일한 것이며 또한 자신의 진정한 자아(아트만)가 무엇인지를 모르는 상태와 동일한 것이라고 본다.

즉 신을 아는 것은 곧 자아를 아는 것이고 이것은 곧 신과 자아가 하나임을 아는 것과 같은 것이라고 말하며, 이 앎을 아트마 즈냐나라고 한다. 그리고 아트마 즈냐나는 오직 사마디를 통해서만 성취될 수 있다고 말한다.

베단타 학파에 따르면, 원래 무수한 차별이 있는 현상 세계를 창조한 신(이슈바라 · 自在神)은 원래 무차별 · 무속성의 브라만이다.[1] 그럼에도 불구하고, 인간은 무지(無知)로 인해 그 같은 사실을 자각하지 못하고 있다.[1] 우주는 요술장이가 만들어낸 것과 같은 환영(마야)의 세계, 즉 무실체의 세계이다.[1] 세계의 환영성을 알게 되면 브라만과 아트만이 본래 동일한 존재라는 자각, 즉 범즉아(梵卽我) · 아즉범(我卽梵)의 범아일여의 진리를 곧바로 깨닫게 되고 그 즉시로 해탈에 도달한다고 하였다.[1]

이와 같은 브라만과 아트만이 둘이 아니며 동일한 하나의 존재라는 베단타 학파의 주장을 불이일원론(不二一元論)이라 한다.[1] 이 불이일원론의 철학에는 불교의 영향이 있어서 다른 힌두교 철학 학파의 공격을 받았으나 결국 힌두교 사상의 주류가 되었다.[1]

같이 보기[편집]

| 위키미디어 공용에 관련된 미디어 분류가 있습니다. |

각주[편집]

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 마 바 사 아 자 차 카 타 파 하 거 종교·철학 > 세계의 종교 > 힌 두 교 > 힌두교 > 힌두교 전사(前史) > 베단타 학파, 《글로벌 세계 대백과사전》

- ↑ Robert E. Hume, Professor Emeritus of History of Religions at the Union Theological Seminary, wrote in Random House's 《The American College Dictionary》 (1966)

- "그것[베단타]은 연대적인 의미와 목적론적인 의미 둘 다에서 베다의 끝과 관계가 있다."

- ↑ 편집자 주: 제사(祭事)와 제사(祭祀)는 구별되어야 한다. 전자는 제사의례(祭祀儀禮) 그 자체 뿐만이 아니라 제사의례(祭祀儀禮)의 실행과 관련된 여러 철학적 · 교의적 · 실천적 사항을 함께 포함하는 개념이다.

Vedanta

| Part of a series on | |

| Hindu philosophy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Orthodox | |

| Heterodox | |

Vedanta (/veɪˈdɑːntə/; Sanskrit: वेदान्त, IAST: Vedānta), also Uttara Mīmāṃsā, is one of the six (āstika) schools of Hindu philosophy. Literally meaning "end of the Vedas", Vedanta reflects ideas that emerged from, or were aligned with, the speculations and philosophies contained in the Upanishads, specifically, knowledge and liberation. Vedanta contains many sub-traditions on the basis of a common textual connection called the Prasthanatrayi: the Upanishads, the Brahma Sutras and the Bhagavad Gita.

All Vedanta schools, in their deliberations, concern themselves with, but differ in their views regarding, ontology, soteriology and epistemology.[1][2] The main traditions of Vedanta are:[3]

- Bhedabheda (difference and non-difference), as early as the 7th century CE,[4] or even the 4th century CE.[5] Some scholars are inclined to consider it as a "tradition" rather than a school of Vedanta.[4]

- Dvaitādvaita or Svabhavikabhedabheda (dualistic non-dualism), founded by Nimbarka[6] in the 7th century CE[7][8]

- Achintya Bheda Abheda (inconceivable one-ness and difference), founded by Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (1486–1534 CE),[9] propagated by Gaudiya Vaishnava

- Advaita (monistic), most prominent Gaudapada (~500 CE)[10] and Adi Shankaracharya (8th century CE)[11]

- Vishishtadvaita (qualified monism), prominent scholars are Nathamuni, Yāmuna and Ramanuja (1017–1137 CE)

- Swaminarayan Darshana, founded by Swaminarayan (1781-1830 CE),[12][13] rooted in Ramanuja's Vishishtadvaita[a]

- Tattvavada (Dvaita) (realistic point of view or dualism), founded by Madhvacharya (1199–1278 CE). The prominent scholars are Jayatirtha (1345-1388 CE), and Vyasatirtha (1460–1539 CE)

- Suddhadvaita (purely non-dual), founded by Vallabha[6] (1479–1531 CE)

Modern developments in Vedanta include Neo-Vedanta,[14][15][16] and the growth of the Swaminarayan Sampradaya.[17] All of these schools, except Advaita Vedanta and Neo-Vedanta, are related to Vaishavism and emphasize devotion, regarding Vishnu or Krishna or a related manifestation, to be the highest Reality.[18][19]

While Advaita Vedanta attracted considerable attention in the West due to the influence of Hindu modernists like Swami Vivekananda, most of the other Vedanta traditions are seen as discourses articulating a form of Vaishnava theology.[20]

Etymology and nomenclature[edit]

The word Vedanta is made of two words :

- Veda (वेद) - refers to the four sacred vedic texts.

- Anta (अंत) - this word means "End".

The word Vedanta literally means the end of the Vedas and originally referred to the Upanishads.[21][22] Vedanta is concerned with the jñānakāṇḍa or knowledge section of the vedas which is called the Upanishads.[23][24] The denotation of Vedanta subsequently widened to include the various philosophical traditions based on to the Prasthanatrayi.[21][25]

The Upanishads may be regarded as the end of Vedas in different senses:[26]

- These were the last literary products of the Vedic period.

- These mark the culmination of Vedic thought.

- These were taught and debated last, in the Brahmacharya (student) stage.[21][27]

Vedanta is one of the six orthodox (āstika) schools of Indian philosophy.[22] It is also called Uttara Mīmāṃsā, which means the 'latter enquiry' or 'higher enquiry'; and is often contrasted with Pūrva Mīmāṃsā, the 'former enquiry' or 'primary enquiry'. Pūrva Mīmāṃsā deals with the karmakāṇḍa or ritualistic section (the Samhita and Brahmanas) in the Vedas.[28][29][b]

Vedanta philosophy[edit]

Common features[edit]

Despite their differences, all schools of Vedanta share some common features:

- Vedanta is the pursuit of knowledge into the Brahman and the Ātman.[31]

- The Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita and the Brahma Sutras constitute the basis of Vedanta ( together known as Prasthanatrayi), providing reliable sources of knowledge (Sruti Śabda in Pramana);[32]

- Brahman, c.q. Ishvara (God), exists as the unchanging material cause and instrumental cause of the world. The only exception here is that Dvaita Vedanta does not hold Brahman to be the material cause, but only the efficient cause.[33]

- The self (Ātman/Jiva) is the agent of its own acts (karma) and the recipient of the consequences of these actions.[34]

- Belief in rebirth and the desirability of release from the cycle of rebirths, (mokṣa).[34]

- Rejection of Buddhism and Jainism and conclusions of the other Vedic schools (Nyaya, Vaisheshika, Samkhya, Yoga, and, to some extent, the Purva Mimamsa).[34]

Prasthanatrayi (the Three Sources)[edit]

The Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita and the Brahma Sutras constitute the basis of Vedanta. All schools of Vedanta propound their philosophy by interpreting these texts, collectively called the Prasthanatrayi, literally, three sources.[23][35]

- The Upanishads,[c] or Śruti prasthāna; considered the Sruti, the "heard" (and repeated) foundation of Vedanta.

- The Brahma Sutras, or Nyaya prasthana / Yukti prasthana; considered the reason-based foundation of Vedanta.

- The Bhagavad Gita, or Smriti prasthāna; considered the Smriti (remembered tradition) foundation of Vedanta.

The Brahma Sutras attempted to synthesize the teachings of the Upanishads. The diversity in the teaching of the Upanishads necessitated the systematization of these teachings. This was likely done in many ways in ancient India, but the only surviving version of this synthesis is the Brahma Sutras of Badarayana.[23]

All major Vedantic teachers, including Shankara, Bhaskara, Ramanuja, Madhva, Nimbarka, and Vallabha have composed commentaries not only on the Upanishads and Brahma Sutras, but also on the Bhagavad Gita. The Bhagavad Gita, due to its syncretism of Samkhya, Yoga, and Upanishadic thought, has played a major role in Vedantic thought.[37]

Metaphysics[edit]

Vedanta philosophies discuss three fundamental metaphysical categories and the relations between the three.[23][38]

- Brahman or Ishvara: the ultimate reality[39]

- Ātman or Jivātman: the individual soul, self[40]

- Prakriti/Jagat:[6] the empirical world, ever-changing physical universe, body and matter[41]

Brahman / Ishvara – Conceptions of the Supreme Reality[edit]

Shankara, in formulating Advaita, talks of two conceptions of Brahman: The higher Brahman as undifferentiated Being, and a lower Brahman endowed with qualities as the creator of the universe.[42]

- Parā or Higher Brahman: The undifferentiated, absolute, infinite, transcendental, supra-relational Brahman beyond all thought and speech is defined as parā Brahman, nirviśeṣa Brahman or nirguṇa Brahman and is the Absolute of metaphysics.

- Aparā or Lower Brahman: The Brahman with qualities defined as aparā Brahman or saguṇa Brahman. The saguṇa Brahman is endowed with attributes and represents the personal God of religion.

Ramanuja, in formulating Vishishtadvaita Vedanta, rejects nirguṇa – that the undifferentiated Absolute is inconceivable – and adopts a theistic interpretation of the Upanishads, accepts Brahman as Ishvara, the personal God who is the seat of all auspicious attributes, as the One reality. The God of Vishishtadvaita is accessible to the devotee, yet remains the Absolute, with differentiated attributes.[43]

Madhva, in expounding Dvaita philosophy, maintains that Vishnu is the supreme God, thus identifying the Brahman, or absolute reality, of the Upanishads with a personal god, as Ramanuja had done before him.[44][45] Nimbarka, in his dvaitadvata philosophy, accepted the Brahman both as nirguṇa and as saguṇa. Vallabha, in his shuddhadvaita philosophy, not only accepts the triple ontological essence of the Brahman, but also His manifestation as personal God (Ishvara), as matter and as individual souls.[46]

Relation between Brahman and Jiva / Atman[edit]

The schools of Vedanta differ in their conception of the relation they see between Ātman / Jivātman and Brahman / Ishvara:[47]

- According to Advaita Vedanta, Ātman is identical with Brahman and there is no difference.[48]

- According to Vishishtadvaita, Jīvātman is different from Ishvara, though eternally connected with Him as His mode.[49] The oneness of the Supreme Reality is understood in the sense of an organic unity (vishistaikya). Brahman / Ishvara alone, as organically related to all Jīvātman and the material universe is the one Ultimate Reality.[50]

- According to Dvaita, the Jīvātman is totally and always different from Brahman / Ishvara.[51]

- According to Shuddhadvaita (pure monism), the Jīvātman and Brahman are identical; both, along with the changing empirically observed universe being Krishna.[52]

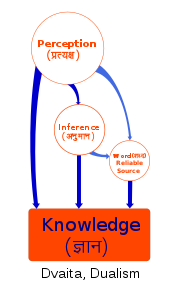

Epistemology[edit]

Pramana[edit]

Pramāṇa (Sanskrit: प्रमाण) literally means "proof", "that which is the means of valid knowledge".[53] It refers to epistemology in Indian philosophies, and encompasses the study of reliable and valid means by which human beings gain accurate, true knowledge.[54] The focus of Pramana is the manner in which correct knowledge can be acquired, how one knows or does not know, and to what extent knowledge pertinent about someone or something can be acquired.[55] Ancient and medieval Indian texts identify six[d] pramanas as correct means of accurate knowledge and truths:[56]

- Pratyakṣa (perception)

- Anumāṇa (inference)

- Upamāṇa (comparison and analogy)

- Arthāpatti (postulation, derivation from circumstances)

- Anupalabdi (non-perception, negative/cognitive proof)

- Śabda (scriptural testimony/ verbal testimony of past or present reliable experts).

The different schools of Vedanta have historically disagreed as to which of the six are epistemologically valid. For example, while Advaita Vedanta accepts all six pramanas,[57] Vishishtadvaita and Dvaita accept only three pramanas (perception, inference and testimony).[58]

Advaita considers Pratyakṣa (perception) as the most reliable source of knowledge, and Śabda, the scriptural evidence, is considered secondary except for matters related to Brahman, where it is the only evidence.[59][e] In Vishistadvaita and Dvaita, Śabda, the scriptural testimony, is considered the most authentic means of knowledge instead.[60]

Theories of cause and effect[edit]

All schools of Vedanta subscribe to the theory of Satkāryavāda,[4] which means that the effect is pre-existent in the cause. But there are two different views on the status of the "effect", that is, the world. Most schools of Vedanta, as well as Samkhya, support Parinamavada, the idea that the world is a real transformation (parinama) of Brahman.[61] According to Nicholson (2010, p. 27), "the Brahma Sutras espouse the realist Parinamavada position, which appears to have been the view most common among early Vedantins". In contrast to Badarayana, Adi Shankara and Advaita Vedantists hold a different view, Vivartavada, which says that the effect, the world, is merely an unreal (vivarta) transformation of its cause, Brahman.[f]

Overview of the main schools of Vedanta[edit]

The Upanishads present an associative philosophical inquiry in the form of identifying various doctrines and then presenting arguments for or against them. They form the basic texts and Vedanta interprets them through rigorous philosophical exegesis to defend the point of view of their specific sampradaya.[62][63] Varying interpretations of the Upanishads and their synthesis, the Brahma Sutras, led to the development of different schools of Vedanta over time.

Vinayak Sakaram Ghate of Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute has done a comparative analysis of the Brahma Sutra commentaries of Nimbarka, Ramanuja, Vallabha, Adi Shankara and Madhvacharya in detail and has written the conclusion that Nimbarka's and Ramanuja's balanced commentaries give the closest meaning of the Brahma_Sutras taking into account of both kinds of Sutras, those which speak of oneness and those which speak of difference.[64] According to Gavin Flood, while Advaita Vedanta is the "most famous" school of Vedanta, and "often, mistakenly, taken to be the only representative of Vedantic thought,"[1] and Shankara a Saivite,[65] "Vedanta is essentially a Vaisnava theological articulation,"[66] a discourse broadly within the parameters of Vaisnavism."[65] Within the Vaishnava traditions four sampradays have special status,[2] while different scholars have classified the Vedanta schools ranging from three to six[21][47][6][67][3][g] as prominent ones.[h]

- Bhedabheda, as early as the 7th century CE,[4] or even the 4th century CE.[5] Some scholars are inclined to consider it as a "tradition" rather than a school of Vedanta.[4]

- Dvaitādvaita or Svabhavikabhedabheda (Vaishnava), founded by Nimbarka[6] in the 7th century CE[7][8]

- Achintya Bheda Abheda (Vaishnava), founded by Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (1486–1534 CE),[9] propagated by Gaudiya Vaishnava

- Advaita (monistic), many scholars of which most prominent are Gaudapada (~500 CE)[10] and Adi Shankaracharya (8th century CE)[11]

- Vishishtadvaita (Vaishnava), prominent scholars are Nathamuni, Yāmuna and Ramanuja (1017–1137 CE)

- Akshar-Purushottam Darshan, based on the teachings of Swaminarayan (1781-1830 CE) and rooted in Ramanuja's Vishishtadvaita;[a] propagated most notably by BAPS[13][69][70][71]

- Tattvavada (Dvaita) (Vaishnava), founded by Madhvacharya (1199–1278 CE). The prominent scholars are Jayatirtha (1345-1388 CE), and Vyasatirtha (1460–1539 CE)

- Suddhadvaita (Vaishnava), founded by Vallabha[6] (1479–1531 CE)

Bhedabheda Vedanta (difference and non-difference)[edit]

Bhedābheda means "difference and non-difference" and is more a tradition than a school of Vedanta. The schools of this tradition emphasize that the individual self (Jīvatman) is both different and not different from Brahman.[4] Notable figures in this school are Bhartriprapancha, Nimbārka (7th century)[7][8] who founded the Dvaitadvaita school, Bhāskara (8th–9th century), Ramanuja's teacher Yādavaprakāśa,[72] Chaitanya (1486–1534) who founded the Achintya Bheda Abheda school, and Vijñānabhikṣu (16th century).[73][i]

Dvaitādvaita Vedanta[edit]

Nimbārka (7th century)[7][8] sometimes identified with Bhāskara,[74] propounded Dvaitādvaita.[75] Brahman (God), souls (chit) and matter or the universe (achit) are considered as three equally real and co-eternal realities. Brahman is the controller (niyanta), the soul is the enjoyer (bhokta), and the material universe is the object enjoyed (bhogya). The Brahman is Krishna, the ultimate cause who is omniscient, omnipotent, all-pervading Being. He is the efficient cause of the universe because, as Lord of Karma and internal ruler of souls, He brings about creation so that the souls can reap the consequences of their karma. God is considered to be the material cause of the universe because creation was a manifestation of His powers of soul (chit) and matter (achit); creation is a transformation (parinama) of God's powers. He can be realized only through a constant effort to merge oneself with His nature through meditation and devotion. [75]

Achintya-Bheda-Abheda Vedanta[edit]

Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (1486 – 1533) was the prime exponent of Achintya-Bheda-Abheda.[76] In Sanskrit achintya means 'inconceivable'.[77] Achintya-Bheda-Abheda represents the philosophy of "inconceivable difference in non-difference",[78] in relation to the non-dual reality of Brahman-Atman which it calls (Krishna), svayam bhagavan.[79] The notion of "inconceivability" (acintyatva) is used to reconcile apparently contradictory notions in Upanishadic teachings. This school asserts that Krishna is Bhagavan of the bhakti yogins, the Brahman of the jnana yogins, and has a divine potency that is inconceivable. He is all-pervading and thus in all parts of the universe (non-difference), yet he is inconceivably more (difference). This school is at the foundation of the Gaudiya Vaishnava religious tradition.[78] The ISKCON or the Hare Krishnas also affiliate to this school of Vedanta Philosophy.

Advaita Vedanta (non-dualism)[edit]

Advaita Vedanta (IAST Advaita Vedānta; Sanskrit: अद्वैत वेदान्त), propounded by Gaudapada (7th century) and Adi Shankara (8th century), espouses non-dualism and monism. Brahman is held to be the sole unchanging metaphysical reality and identical to the individual Atman.[45] The physical world, on the other hand, is always-changing empirical Maya.[80][j] The absolute and infinite Atman-Brahman is realized by a process of negating everything relative, finite, empirical and changing.[81]

The school accepts no duality, no limited individual souls (Atman / Jivatman), and no separate unlimited cosmic soul. All souls and their existence across space and time are considered to be the same oneness. [82] Spiritual liberation in Advaita is the full comprehension and realization of oneness, that one's unchanging Atman (soul) is the same as the Atman in everyone else, as well as being identical to Brahman.[83]

Vishishtadvaita Vedanta (qualified non-dualism)[edit]

Vishishtadvaita, propounded by Ramanuja (11–12th century), asserts that Jivatman (human souls) and Brahman (as Vishnu) are different, a difference that is never transcended.[84][85] With this qualification, Ramanuja also affirmed monism by saying that there is unity of all souls and that the individual soul has the potential to realize identity with the Brahman.[86] Vishishtadvaita, like Advaita, is a non-dualistic school of Vedanta in a qualified way, and both begin by assuming that all souls can hope for and achieve the state of blissful liberation.[87] On the relation between the Brahman and the world of matter (Prakriti), Vishishtadvaita states both are two different absolutes, both metaphysically true and real, neither is false or illusive, and that saguna Brahman with attributes is also real.[88] Ramanuja states that God, like man, has both soul and body, and the world of matter is the glory of God's body.[89] The path to Brahman (Vishnu), according to Ramanuja, is devotion to godliness and constant remembrance of the beauty and love of the personal god (bhakti of saguna Brahman).[90]

Swaminarayan Darshana[edit]

The Swaminarayan Darshana, also called Akshar Purushottam Darshan by the BAPS, was propounded by Swaminarayan (1781-1830 CE) and is rooted in Ramanuja's Vishishtadvaita.[a] It asserts that Parabrahman (Purushottam, Narayana) and Aksharbrahman are two distinct eternal realities. Adherents believe that they can achieve moksha, or freedom from the cycle of birth and death, by becoming aksharrup (or brahmarup), that is, by attaining qualities similar to Akshar (or Aksharbrahman) and worshipping Purushottam (or Parabrahman; the supreme living entity; God).[91][92]

Tattvavada Vedanta (Dvaita)(dualism)[edit]

Tattvavada, propounded by Madhvacharya (13th century), is based on the premise of realism or realistic point of view. The term Dvaita which means dualism was later applied to Madhvacharya's philosophy. Atman (soul) and Brahman (as Vishnu) are understood as two completely different entities.[93] Brahman is the creator of the universe, perfect in knowledge, perfect in knowing, perfect in its power, and distinct from souls, distinct from matter.[94] [k] In Dvaita Vedanta, an individual soul must feel attraction, love, attachment and complete devotional surrender to Vishnu for salvation, and it is only His grace that leads to redemption and salvation.[97] Madhva believed that some souls are eternally doomed and damned, a view not found in Advaita and Vishishtadvaita Vedanta.[98] While the Vishishtadvaita Vedanta asserted "qualitative monism and quantitative pluralism of souls", Madhva asserted both "qualitative and quantitative pluralism of souls".[99]

Shuddhādvaita Vedanta (pure nondualism)[edit]

Shuddhadvaita (pure non-dualism), propounded by Vallabhacharya (1479–1531 CE), states that the entire universe is real and is subtly Brahman only in the form of Krishna.[52] Vallabhacharya agreed with Advaita Vedanta's ontology, but emphasized that prakriti (empirical world, body) is not separate from the Brahman, but just another manifestation of the latter.[52] Everything, everyone, everywhere – soul and body, living and non-living, jiva and matter – is the eternal Krishna.[52] The way to Krishna, in this school, is bhakti. Vallabha opposed renunciation of monistic sannyasa as ineffective and advocates the path of devotion (bhakti) rather than knowledge (jnana). The goal of bhakti is to turn away from ego, self-centered-ness and deception, and to turn towards the eternal Krishna in everything continually offering freedom from samsara.[52]

History[edit]

The history of Vedanta can be divided into two periods: one prior to the composition of the Brahma Sutras and the other encompassing the schools that developed after the Brahma Sutras were written. Until the 11th century, Vedanta was a peripheral school of thought.[100]

Before the Brahma Sutras (before the 5th century)[edit]

Little is known[101] of schools of Vedanta existing before the composition of the Brahma Sutras (400–450 CE).[102][5][l] It is clear that Badarayana, the writer of Brahma Sutras, was not the first person to systematize the teachings of the Upanishads, as he quotes six Vedantic teachers before him – Ashmarathya, Badari, Audulomi, Kashakrtsna, Karsnajini and Atreya.[104][105] References to other early Vedanta teachers – Brahmadatta, Sundara, Pandaya, Tanka and Dravidacharya – are found in secondary literature of later periods.[106] The works of these ancient teachers have not survived, but based on the quotes attributed to them in later literature, Sharma postulates that Ashmarathya and Audulomi were Bhedabheda scholars, Kashakrtsna and Brahmadatta were Advaita scholars, while Tanka and Dravidacharya were either Advaita or Vishistadvaita scholars.[105]

Brahma Sutras (completed in the 5th century)[edit]

Badarayana summarized and interpreted teachings of the Upanishads in the Brahma Sutras, also called the Vedanta Sutra,[107][m] possibly "written from a Bhedābheda Vedāntic viewpoint."[4] Badarayana summarized the teachings of the classical Upanishads[108][109][n] and refuted the rival philosophical schools in ancient India.Nicholson 2010, p. 26 The Brahma Sutras laid the basis for the development of Vedanta philosophy.[110]

Though attributed to Badarayana, the Brahma Sutras were likely composed by multiple authors over the course of hundreds of years.[5] The estimates on when the Brahma Sutras were complete vary,[111][112] with Nakamura in 1989 and Nicholson in his 2013 review stating, that they were most likely compiled in the present form around 400–450 CE.[102][o] Isaeva suggests they were complete and in current form by 200 CE,[113] while Nakamura states that "the great part of the Sutra must have been in existence much earlier than that."[112]

The book is composed of four chapters, each divided into four-quarters or sections.[23] These sutras attempt to synthesize the diverse teachings of the Upanishads. However, the cryptic nature of aphorisms of the Brahma Sutras have required exegetical commentaries.[114] These commentaries have resulted in the formation of numerous Vedanta schools, each interpreting the texts in its own way and producing its own commentary.[115]

Between the Brahma Sutras and Adi Shankara (5th–8th centuries)[edit]

Little with specificity is known of the period between the Brahma Sutras (5th century CE) and Adi Shankara (8th century CE).[101][11] Only two writings of this period have survived: the Vākyapadīya, written by Bhartṛhari (second half 5th century,[116]) and the Kārikā written by Gaudapada (early 6th[11] or 7th century[101] CE).

Shankara mentions 99 different predecessors of his school in his commentaries.[117] A number of important early Vedanta thinkers have been listed in the Siddhitraya by Yamunācārya (c. 1050), the Vedārthasamgraha by Rāmānuja (c. 1050–1157), and the Yatīndramatadīpikā by Śrīnivāsa Dāsa.[101] At least fourteen thinkers are known to have existed between the composition of the Brahma Sutras and Shankara's lifetime.[p]

A noted scholar of this period was Bhartriprapancha. Bhartriprapancha maintained that the Brahman is one and there is unity, but that this unity has varieties. Scholars see Bhartriprapancha as an early philosopher in the line who teach the tenet of Bhedabheda.[23]

Gaudapada, Adi Shankara (Advaita Vedanta) (6th–9th centuries)[edit]

Influenced by Buddhism, Advaita vedanta departs from the bhedabheda-philosophy, instead postulating the identity of Atman with the Whole (Brahman),

Gaudapada[edit]

Gaudapada (c. 6th century CE),[118] was the teacher or a more distant predecessor of Govindapada,[119] the teacher of Adi Shankara. Shankara is widely considered as the apostle of Advaita Vedanta.[47] Gaudapada's treatise, the Kārikā – also known as the Māṇḍukya Kārikā or the Āgama Śāstra[120] – is the earliest surviving complete text on Advaita Vedanta.[q]

Gaudapada's Kārikā relied on the Mandukya, Brihadaranyaka and Chhandogya Upanishads.[124] In the Kārikā, Advaita (non-dualism) is established on rational grounds (upapatti) independent of scriptural revelation; its arguments are devoid of all religious, mystical or scholastic elements. Scholars are divided on a possible influence of Buddhism on Gaudapada's philosophy.[r] The fact that Shankara, in addition to the Brahma Sutras, the principal Upanishads and the Bhagvad Gita, wrote an independent commentary on the Kārikā proves its importance in Vedāntic literature.[125]

Adi Shankara[edit]

Adi Shankara (788–820), elaborated on Gaudapada's work and more ancient scholarship to write detailed commentaries on the Prasthanatrayi and the Kārikā. The Mandukya Upanishad and the Kārikā have been described by Shankara as containing "the epitome of the substance of the import of Vedanta".[125] It was Shankara who integrated Gaudapada work with the ancient Brahma Sutras, "and give it a locus classicus" alongside the realistic strain of the Brahma Sutras.[126][s]

A noted contemporary of Shankara was Maṇḍana Miśra, who regarded Mimamsa and Vedanta as forming a single system and advocated their combination known as Karma-jnana-samuchchaya-vada.[127][t] The treatise on the differences between the Vedanta school and the Mimamsa school was a contribution of Adi Shankara. Advaita Vedanta rejects rituals in favor of renunciation, for example.[128]

[edit]

Early Vaishnava Vedanta retains the tradition of bhedabheda, equating Brahman with Vishnu or Krishna.

Nimbārka and Dvaitādvaita[edit]

Nimbārka (7th century)[7][8] sometimes identified with Bhāskara,[74] propounded Dvaitādvaita or Bhedābheda.[75]

Bhāskara and Upadhika[edit]

Bhāskara (8th–9th century) also taught Bhedabheda. In postulating Upadhika, he considers both identity and difference to be equally real. As the causal principle, Brahman is considered non-dual and formless pure being and intelligence.[129] The same Brahman, manifest as events, becomes the world of plurality. Jīva is Brahman limited by the mind. Matter and its limitations are considered real, not a manifestation of ignorance. Bhaskara advocated bhakti as dhyana (meditation) directed toward the transcendental Brahman. He refuted the idea of Maya and denied the possibility of liberation in bodily existence.[130]

[edit]

The Bhakti movement of late medieval Hinduism started in the 7th-century, but rapidly expanded after the 12th-century.[131] It was supported by the Puranic literature such as the Bhagavata Purana, poetic works, as well as many scholarly bhasyas and samhitas.[132][133][134]

This period saw the growth of Vashnavism Sampradayas (denominations or communities) under the influence of scholars such as Ramanujacharya, Vedanta Desika, Madhvacharya and Vallabhacharya.[135] Bhakti poets or teachers such as Manavala Mamunigal, Namdev, Ramananda, Surdas, Tulsidas, Eknath, Tyagaraja, Chaitanya Mahaprabhu and many others influenced the expansion of Vaishnavism.[136] These Vaishnavism sampradaya founders challenged the then dominant Shankara's doctrines of Advaita Vedanta, particularly Ramanuja in the 12th century, Vedanta Desika and Madhva in the 13th, building their theology on the devotional tradition of the Alvars (Shri Vaishnavas),[137] and Vallabhacharya in the 16th century.

In North and Eastern India, Vaishnavism gave rise to various late Medieval movements: Ramananda in the 14th century, Sankaradeva in the 15th and Vallabha and Chaitanya in the 16th century.

Ramanuja (Vishishtadvaita Vedanta) (11th–12th centuries)[edit]

Rāmānuja (1017–1137 CE) was the most influential philosopher in the Vishishtadvaita tradition. As the philosophical architect of Vishishtadvaita, he taught qualified non-dualism.[138] Ramanuja's teacher, Yadava Prakasha, followed the Advaita monastic tradition. Tradition has it that Ramanuja disagreed with Yadava and Advaita Vedanta, and instead followed Nathamuni and Yāmuna. Ramanuja reconciled the Prasthanatrayi with the theism and philosophy of the Vaishnava Alvars poet-saints.[139] Ramanuja wrote a number of influential texts, such as a bhasya on the Brahma Sutras and the Bhagavad Gita, all in Sanskrit.[140]

Ramanuja presented the epistemological and soteriological importance of bhakti, or the devotion to a personal God (Vishnu in Ramanuja's case) as a means to spiritual liberation. His theories assert that there exists a plurality and distinction between Atman (souls) and Brahman (metaphysical, ultimate reality), while he also affirmed that there is unity of all souls and that the individual soul has the potential to realize identity with the Brahman.[86] Vishishtadvaiata provides the philosophical basis of Sri Vaishnavism.[141]

Ramanuja was influential in integrating Bhakti, the devotional worship, into Vedanta premises.[142]

Madhva (Tattvavada or Dvaita Vedanta)(13th–14th centuries)[edit]

Tattvavada[u] or Dvaita Vedanta was propounded by Madhvacharya (1238–1317 CE).[v] He presented the opposite interpretation of Shankara in his Dvaita, or dualistic system.[145] In contrast to Shankara's non-dualism and Ramanuja's qualified non-dualism, he championed unqualified dualism. Madhva wrote commentaries on the chief Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita and the Brahma Sutra.[146]

Madhva started his Vedic studies at age seven, joined an Advaita Vedanta monastery in Dwarka (Gujarat),[147] studied under guru Achyutrapreksha,[148] frequently disagreed with him, left the Advaita monastery, and founded Dvaita.[149] Madhva and his followers Jayatirtha and Vyasatirtha, were critical of all competing Hindu philosophies, Jainism and Buddhism,[150] but particularly intense in their criticism of Advaita Vedanta and Adi Shankara.[151]

Dvaita Vedanta is theistic and it identifies Brahman with Narayana, or more specifically Vishnu, in a manner similar to Ramanuja's Vishishtadvaita Vedanta. But it is more explicitly pluralistic.[152] Madhva's emphasis for difference between soul and Brahman was so pronounced that he taught there were differences (1) between material things; (2) between material things and souls; (3) between material things and God; (4) between souls; and (5) between souls and God.[153] He also advocated for a difference in degrees in the possession of knowledge. He also advocated for differences in the enjoyment of bliss even in the case of liberated souls, a doctrine found in no other system of Indian philosophy.[152]

Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (Achintya Bheda Abheda) (16th century)[edit]

Achintya Bheda Abheda (Vaishnava), founded by Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (1486–1534 CE),[9] was propagated by Gaudiya Vaishnava. Historically, it was Chaitanya Mahaprabhu who founded congregational chanting of holy names of Krishna in the early 16th century after becoming a sannyasi.[154]

Modern times (19th century – present)[edit]

Swaminarayan and Akshar-Purushottam Darshan (19th century)[edit]

The Swaminarayan Darshana, which is rooted in Ramanuja's Vishishtadvaita,[155][71][156][a] was founded in 1801 by Swaminarayan (1781-1830 CE), and is contemporarily most notably propagated by BAPS.[157] Due to the commentarial work of Bhadreshdas Swami, the Akshar-Purushottam teachings were recognized as a distinct school of Vedanta by the Shri Kashi Vidvat Parishad in 2017[13][69] and by members of the 17th World Sanskrit Conference in 2018.[13][w][70] Swami Paramtattvadas describes the Akshar-Purushottam teachings as "a distinct school of thought within the larger expanse of classical Vedanta,"[158] presenting the Akshar-Purushottam teachings as a seventh school of Vedanta.[159]

Neo-Vedanta (19th century)[edit]

Neo-Vedanta, variously called as "Hindu modernism", "neo-Hinduism", and "neo-Advaita", is a term that denotes some novel interpretations of Hinduism that developed in the 19th century,[160] presumably as a reaction to the colonial British rule.[161] King (2002, pp. 129–135) writes that these notions accorded the Hindu nationalists an opportunity to attempt the construction of a nationalist ideology to help unite the Hindus to fight colonial oppression. Western orientalists, in their search for its "essence", attempted to formulate a notion of "Hinduism" based on a single interpretation of Vedanta as a unified body of religious praxis.[162] This was contra-factual as, historically, Hinduism and Vedanta had always accepted a diversity of traditions. King (1999, pp. 133–136) asserts that the neo-Vedantic theory of "overarching tolerance and acceptance" was used by the Hindu reformers, together with the ideas of Universalism and Perennialism, to challenge the polemic dogmatism of Judaeo-Christian-Islamic missionaries against the Hindus.

The neo-Vedantins argued that the six orthodox schools of Hindu philosophy were perspectives on a single truth, all valid and complementary to each other.[163] Halbfass (2007, p. 307) sees these interpretations as incorporating western ideas[164] into traditional systems, especially Advaita Vedanta.[165] It is the modern form of Advaita Vedanta, states King (1999, p. 135), the neo-Vedantists subsumed the Buddhist philosophies as part of the Vedanta tradition[x] and then argued that all the world religions are same "non-dualistic position as the philosophia perennis", ignoring the differences within and outside of Hinduism.[167] According to Gier (2000, p. 140), neo-Vedanta is Advaita Vedanta which accepts universal realism:

A major proponent in the popularization of this Universalist and Perennialist interpretation of Advaita Vedanta was Vivekananda,[168] who played a major role in the revival of Hinduism.[169] He was also instrumental in the spread of Advaita Vedanta to the West via the Vedanta Society, the international arm of the Ramakrishna Order.[170][page needed]

Criticism of Neo-Vedanta label[edit]

Nicholson (2010, p. 2) writes that the attempts at integration which came to be known as neo-Vedanta were evident as early as between the 12th and the 16th century−

Matilal criticizes Neo-Hinduism as an oddity developed by West-inspired Western Indologists and attributes it to the flawed Western perception of Hinduism in modern India. In his scathing criticism of this school of reasoning, Matilal (2002, pp. 403–404) says:

Influence[edit]

According to Nakamura (2004, p. 3), the Vedanta school has had a historic and central influence on Hinduism:

Frithjof Schuon summarizes the influence of Vedanta on Hinduism as follows:

Gavin Flood states,

Hindu traditions[edit]

Vedanta, adopting ideas from other orthodox (āstika) schools, became the most prominent school of Hinduism.[23][176] Vedanta traditions led to the development of many traditions in Hinduism.[22][177] Sri Vaishnavism of south and southeastern India is based on Ramanuja's Vishishtadvaita Vedanta.[178] Ramananda led to the Vaishnav Bhakti Movement in north, east, central and west India. This movement draws its philosophical and theistic basis from Vishishtadvaita. A large number of devotional Vaishnavism traditions of east India, north India (particularly the Braj region), west and central India are based on various sub-schools of Bhedabheda Vedanta.[4] Advaita Vedanta influenced Krishna Vaishnavism in the northeastern state of Assam.[179] The Madhva school of Vaishnavism found in coastal Karnataka is based on Dvaita Vedanta.[151]

Āgamas, the classical literature of Shaivism, though independent in origin, show Vedanta association and premises.[180] Of the 92 Āgamas, ten are (dvaita) texts, eighteen (bhedabheda), and sixty-four (advaita) texts.[181] While the Bhairava Shastras are monistic, Shiva Shastras are dualistic.[182] Isaeva (1995, pp. 134–135) finds the link between Gaudapada's Advaita Vedanta and Kashmir Shaivism evident and natural. Tirumular, the Tamil Shaiva Siddhanta scholar, credited with creating "Vedanta–Siddhanta" (Advaita Vedanta and Shaiva Siddhanta synthesis), stated, "becoming Shiva is the goal of Vedanta and Siddhanta; all other goals are secondary to it and are vain."[183]

Shaktism, or traditions where a goddess is considered identical to Brahman, has similarly flowered from a syncretism of the monist premises of Advaita Vedanta and dualism premises of Samkhya–Yoga school of Hindu philosophy, sometimes referred to as Shaktadavaitavada (literally, the path of nondualistic Shakti).[184]

Influence on Western thinkers[edit]

An exchange of ideas has been taking place between the western world and Asia since the late 18th century as a result of colonization of parts of Asia by Western powers. This also influenced western religiosity. The first translation of Upanishads, published in two parts in 1801 and 1802, significantly influenced Arthur Schopenhauer, who called them the consolation of his life.[185] He drew explicit parallels between his philosophy, as set out in The World as Will and Representation,[186] and that of the Vedanta philosophy as described in the work of Sir William Jones.[187] Early translations also appeared in other European languages.[188] Influenced by Śaṅkara's concepts of Brahman (God) and māyā (illusion), Lucian Blaga often used the concepts marele anonim (the Great Anonymous) and cenzura transcendentă (the transcendental censorship) in his philosophy.[189]

Similarities with Spinoza's philosophy[edit]

German Sanskritist Theodore Goldstücker was among the early scholars to notice similarities between the religious conceptions of the Vedanta and those of the Dutch Jewish philosopher Baruch Spinoza, writing that Spinoza's thought was

Max Müller noted the striking similarities between Vedanta and the system of Spinoza, saying,

Helena Blavatsky, a founder of the Theosophical Society, also compared Spinoza's religious thought to Vedanta, writing in an unfinished essay,

See also[edit]

- Badarayana

- Monistic idealism

- List of teachers of Vedanta

- Self-consciousness (Vedanta)

- Śāstra pramāṇam in Hinduism

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c d Vishishtadvaita roots:

* Supreme Court of India, 1966 AIR 1119, 1966 SCR (3) 242: "Philosophically, Swaminarayan was a follower of Ramanuja"[156]

* Hanna H. Kim: "The philosophical foundation for Swaminarayan devotionalism is the viśiṣṭādvaita, or qualified non-dualism, of Rāmānuja (1017–1137 ce)."[155] - ^ Historically, Vedanta has been called by various names. The early names were the Upanishadic ones (Aupanisada), the doctrine of the end of the Vedas (Vedanta-vada), the doctrine of Brahman (Brahma-vada), and the doctrine that Brahma is the cause (Brahma-karana-vada).[30]

- ^ The Upanishads were many in number and developed in the different schools at different times and places, some in the Vedic period and others in the medieval or modern era (the names of up to 112 Upanishads have been recorded).[36] All major commentators have considered twelve to thirteen oldest of these texts as the Principal Upanishads and as the foundation of Vedanta.

- ^ A few Indian scholars such as Vedvyasa discuss ten; Krtakoti discusses eight; six is most widely accepted: see Nicholson (2010, pp. 149–150)

- ^ Anantanand Rambachan (1991, pp. xii–xiii) states, "According to these [widely represented contemporary] studies, Shankara only accorded a provisional validity to the knowledge gained by inquiry into the words of the Śruti (Vedas) and did not see the latter as the unique source (pramana) of Brahmajnana. The affirmations of the Śruti, it is argued, need to be verified and confirmed by the knowledge gained through direct experience (anubhava) and the authority of the Śruti, therefore, is only secondary." Sengaku Mayeda (2006, pp. 46–47) concurs, adding Shankara maintained the need for objectivity in the process of gaining knowledge (vastutantra), and considered subjective opinions (purushatantra) and injunctions in Śruti (codanatantra) as secondary. Mayeda cites Shankara's explicit statements emphasizing epistemology (pramana–janya) in section 1.18.133 of Upadesasahasri and section 1.1.4 of Brahmasutra–bhasya.

- ^ Nicholson (2010, p. 27) writes of Advaita Vedantin position of cause and effect - Although Brahman seems to undergo a transformation, in fact no real change takes place. The myriad of beings are essentially unreal, as the only real being is Brahman, that ultimate reality which is unborn, unchanging, and entirely without parts.

- ^ Sivananda also mentions Meykandar and the Shaiva Siddhanta philosophy.[68]

- ^ Proponents of other Vedantic schools continue to write and develop their ideas as well, although their works are not widely known outside of smaller circles of followers in India.

- ^ According to Nakamura and Dasgupta, the Brahmasutras reflect a Bhedabheda point of view,[5] the most influential tradition of Vedanta before Shankara. Numerous Indologists, including Surendranath Dasgupta, Paul hacker, Hajime Nakamura, and Mysore Hiriyanna, have described Bhedabheda as the most influential school of Vedanta before Shankara.[5]

- ^ O'Flaherty (1986, p. 119) says "that to say that the universe is an illusion (māyā) is not to say that it is unreal; it is to say, instead, that it is not what it seems to be, that it is something constantly being made. Maya not only deceives people about the things they think they know; more basically, it limits their knowledge."

- ^ The concept of Brahman in Dvaita Vedanta is so similar to the monotheistic eternal God, that some early colonial–era Indologists such as George Abraham Grierson suggested Madhva was influenced by early Christians who migrated to India, [95] but later scholarship has rejected this theory.[96]

- ^ Nicholson (2010, p. 26) considers the Brahma Sutras as a group of sutras composed by multiple authors over the course of hundreds of years. The precise date is disputed.[103] Nicholson (2010, p. 26) estimates that the book was composed in its current form between 400 and 450 CE. The reference shows BCE, but it's a typo in Nicholson's book

- ^ The Vedanta–sūtra are known by a variety of names, including (1) Brahma–sūtra, (2) Śārīraka–sutra, (3) Bādarāyaṇa–sūtra and (4) Uttara–mīmāṁsā.

- ^ Estimates of the date of Bādarāyana's lifetime differ. Pandey 2000, p. 4

- ^ Nicholson 2013, p. 26 Quote: "From a historical perspective, the Brahmasutras are best understood as a group of sutras composed by multiple authors over the course of hundreds of years, most likely composed in its current form between 400 and 450 BCE." This dating has a typo in Nicholson's book, it should be read "between 400 and 450 CE"

- ^ Bhartŗhari (c. 450–500), Upavarsa (c. 450–500), Bodhāyana (c. 500), Tanka (Brahmānandin) (c. 500–550), Dravida (c. 550), Bhartŗprapañca (c. 550), Śabarasvāmin (c. 550), Bhartŗmitra (c. 550–600), Śrivatsānka (c. 600), Sundarapāndya (c. 600), Brahmadatta (c. 600–700), Gaudapada (c. 640–690), Govinda (c. 670–720), Mandanamiśra (c. 670–750)[101]

- ^ There is ample evidence, however, to suggest that Advaita was a thriving tradition by the start of the common era or even before that. Shankara mentions 99 different predecessors of his Sampradaya.[117] Scholarship since 1950 suggests that almost all Sannyasa Upanishads have a strong Advaita Vedanta outlook.[121] Six Sannyasa Upanishads – Aruni, Kundika, Kathashruti, Paramahamsa, Jabala and Brahma – were composed before the 3rd Century CE, likely in the centuries before or after the start of the common era; the Asrama Upanishad is dated to the 3rd Century.[122] The strong Advaita Vedanta views in these ancient Sannyasa Upanishads may be, states Patrick Olivelle, because major Hindu monasteries of this period belonged to the Advaita Vedanta tradition.[123]

- ^ Scholars like Raju (1992, p. 177), following the lead of earlier scholars like Sengupta,[125] believe that Gaudapada co-opted the Buddhist doctrine that ultimate reality is pure consciousness (vijñapti-mātra). Raju (1992, pp. 177–178) states, "Gaudapada wove [both doctrines] into a philosophy of the Mandukaya Upanisad, which was further developed by Shankara." Nikhilananda (2008, pp. 203–206) states that the whole purpose of Gaudapada was to present and demonstrate the ultimate reality of Atman, an idea denied by Buddhism. According to Murti (1955, pp. 114–115), Gaudapada's doctrines are unlike Buddhism. Gaudapada's influential text consists of four chapters: Chapters One, Two, and Three are entirely Vedantin and founded on the Upanishads, with little Buddhist flavor. Chapter Four uses Buddhist terminology and incorporates Buddhist doctrines but Vedanta scholars who followed Gaudapada through the 17th century, state that both Murti and Richard King never referenced nor used Chapter Four, they only quote from the first three.[10] While there is shared terminology, the doctrines of Gaudapada and Buddhism are fundamentally different, states Murti (1955, pp. 114–115)

- ^ Nicholson (2010, p. 27) writes: "The Brahmasutras themselves espouse the realist Parinamavada position, which appears to have been the view most common among early Vedantins."

- ^ According to Mishra, the sutras, beginning with the first sutra of Jaimini and ending with the last sutra of Badarayana, form one compact shastra.[127]

- ^ Madhvacharya gave his philosophy the name Tattvavada (realistic point of view or realism), but later after few centuries it was popularised as Dvaita Vedanta (dualism).

- ^ Many sources date him to 1238–1317 period,[143] but some place him over 1199–1278 CE.[144]

- ^ "Professor Ashok Aklujkar said [...] Just as the Kashi Vidvat Parishad acknowledged Swaminarayan Bhagwan's Akshar-Purushottam Darshan as a distinct darshan in the Vedanta tradition, we are honored to do the same from the platform of the World Sanskrit Conference [...] Professor George Cardona [said] "This is a very important classical Sanskrit commentary that very clearly and effectively explains that Akshar is distinct from Purushottam."[13]

- ^ Vivekananda, clarifies Richard King, stated, "I am not a Buddhist, as you have heard, and yet I am"; but thereafter Vivekananda explained that "he cannot accept the Buddhist rejection of a self, but nevertheless honors the Buddha's compassion and attitude towards others".[166]

- ^ The tendency of "a blurring of philosophical distinctions" has also been noted by Burley.[171] Lorenzen locates the origins of a distinct Hindu identity in the interaction between Muslims and Hindus,[172] and a process of "mutual self-definition with a contrasting Muslim other",[173] which started well before 1800.[174]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Flood 1996, p. 239.

- ^ a b Flood 1996, p. 133.

- ^ a b Dandekar 1987.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Nicholson.

- ^ a b c d e f Nicholson 2010, p. 26.

- ^ a b c d e f Pahlajrai, Prem. "Vedanta: A Comparative Analysis of Diverse Schools" (PDF). Asian Languages and Literature. University of Washington.

- ^ a b c d e Malkovsky 2001, p. 118.

- ^ a b c d e Ramnarace 2014, p. 180.

- ^ a b c Sivananda 1993, p. 248.

- ^ a b c Jagannathan 2011.

- ^ a b c d Comans 2000, p. 163.

- ^ Swaminarayan Hinduism : tradition, adaptation and identity. Raymond Brady Williams, Yogi Trivedi (1st ed.). New Delhi, India: Oxford University Press. 2016. ISBN 978-0-19-908657-3. OCLC 948338914.

- ^ a b c d e "HH Mahant Swami Maharaj Inaugurates the Svāminārāyaṇasiddhāntasudhā and Announces Parabrahman Svāminārāyaṇa's Darśana as the Akṣara-Puruṣottama Darśana". BAPS Swaminarayan Sanstha. 17 September 2017.

- ^ King 1999, p. 135.

- ^ Flood 1996, p. 258.

- ^ King 2002, p. 93.

- ^ Williams 2018.

- ^ Sharma 2008, p. 2–10.

- ^ Cornille 2019.

- ^ Flood 1996, pp. 238, 246.

- ^ a b c d Chatterjee & Dutta 2007, pp. 317–318.

- ^ a b c d Flood 1996, pp. 231–232, 238.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hiriyanna 2008, pp. 19, 21–25, 150–152.

- ^ Koller 2013, pp. 100–106; Sharma 1994, p. 211

- ^ Raju 1992, pp. 176–177; Isaeva 1992, p. 35 with footnote 30

- ^ Raju 1992, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Scharfe 2002, pp. 58–59, 115–120, 282–283.

- ^ Clooney 2000, pp. 147–158.

- ^ Jaimini 1999, p. 16, Sutra 30.

- ^ King 1995, p. 268 with note 2.

- ^ Fowler 2002, pp. 34, 66; Flood 1996, pp. 238–239

- ^ Fowler 2002, pp. 34, 66.

- ^ Das 1952; Doniger & Stefon 2015; Lochtefeld 2000, p. 122; Sheridan 1991, p. 136

- ^ a b c Doniger & Stefon 2015.

- ^ Ranganathan; Grimes 1990, pp. 6–7

- ^ Dasgupta 2012, pp. 28.

- ^ Pasricha 2008, p. 95.

- ^ Raju 1992, pp. 176–177, 505–506; Fowler 2002, pp. 49–59, 254, 269, 294–295, 345

- ^ Das 1952; Puligandla 1997, p. 222

- ^ Jones & Ryan 2006, p. 51; Johnson 2009, p. 'see entry for Atman(self)'

- ^ Lipner 1986, pp. 40–41, 51–56, 144; Hiriyanna 2008, pp. 23, 78, 158–162

- ^ Chari 1988, pp. 2, 383.

- ^ Fowler 2002, p. 317; Chari 1988, pp. 2, 383

- ^ "Dvaita". Britannica. Retrieved 2016-08-31.

- ^ a b Stoker 2011.

- ^ Vitsaxis 2009, pp. 100–101.

- ^ a b c Raju 1992, p. 177.

- ^ Raju 1992, p. 177; Stoker 2011

- ^ Ādidevānanda 2014, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Betty 2010, pp. 215–224; Stoker 2011; Chari 1988, pp. 2, 383

- ^ Craig 2000, pp. 517–18; Stoker 2011; Bryant 2007, pp. 361–363

- ^ a b c d e Bryant 2007, pp. 479–481.

- ^ Lochtefeld 2000, pp. 520–521; Chari 1988, pp. 73–76

- ^ Lochtefeld 2000, pp. 520–521.

- ^ Potter 2002, pp. 25–26; Bhawuk 2011, p. 172

- ^ Bhawuk 2011, p. 172; Chari 1988, pp. 73–76; Flood 1996, pp. 225

- ^ Grimes 2006, p. 238; Puligandla 1997, p. 228; Clayton 2006, pp. 53–54

- ^ Grimes 2006, p. 238.

- ^ Indich 1995, pp. 65; Gupta 1995, pp. 137–166

- ^ Fowler 2002, p. 304; Puligandla 1997, pp. 208–211, 237–239; Sharma 2000, pp. 147–151

- ^ Nicholson 2010, p. 27.

- ^ Balasubramanian 2000, pp. xxx–xxxiiii.

- ^ Deutsch & Dalvi 2004, pp. 95–96.

- ^ [1] Comparative analysis of Brahma Sutra commentaries

- ^ a b Flood 1996, p. 246.

- ^ Flood 1996, p. 238.

- ^ Sivananda 1993, p. 216.

- ^ Sivananda 1993, p. 217.

- ^ a b "Acclamation by th Sri Kasi Vidvat Parisad". BAPS Swaminarayan Sanstha. 31 July 2017.

- ^ a b Paramtattvadas 2019, p. 40.

- ^ a b Williams 2018, p. 38.

- ^ Nicholson 2013, p. 34.

- ^ Nicholson; Sivananda 1993, p. 247

- ^ a b "Nimbarka". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ a b c Sharma 1994, p. 376.

- ^ Sivananda 1993, p. 247.

- ^ Bryant 2007, p. 407; Gupta 2007, pp. 47–52

- ^ a b Bryant 2007, pp. 378–380.

- ^ Gupta 2016, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Das 1952; Hiriyanna 2008, pp. 160–161; O'Flaherty 1986, p. 119

- ^ Das 1952.

- ^ Sharma 2007, pp. 19–40, 53–58, 79–86.

- ^ Indich 1995, pp. 1–2, 97–102; Etter 2006, pp. 57–60, 63–65; Perrett 2013, pp. 247–248

- ^ "Similarity to Brahman". The Hindu. 6 January 2020. Retrieved 2020-01-11 – via www.pressreader.com.

- ^ Betty 2010, pp. 215–224; Craig 2000, pp. 517–518

- ^ a b Bartley 2013, pp. 1–2, 9–10, 76–79, 87–98; Sullivan 2001, p. 239; Doyle 2006, pp. 59–62

- ^ Etter 2006, pp. 57–60, 63–65; van Buitenin 2010

- ^ Schultz 1981, pp. 81–84.

- ^ van Buitenin 2010.

- ^ Schultz 1981, pp. 81–84; van Buitenin 2010; Sydnor 2012, pp. 84–87

- ^ Bhadreshdas, Sadhu; Aksharananddas, Sadhu (1 April 2016), "Swaminarayan's Brahmajnana as Aksarabrahma-Parabrahma-Darsanam", Swaminarayan Hinduism, Oxford University Press, pp. 172–190, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199463749.003.0011, ISBN 978-0-19-946374-9, retrieved 2021-10-26

- ^ Padoux, André (1 April 2002). "Raymond Brady Williams, An Introduction to Swaminarayan Hinduism". Archives de sciences sociales des religions (118): 87–151. doi:10.4000/assr.1703. ISSN 0335-5985.

- ^ Stoker 2011; von Dehsen 1999, p. 118

- ^ Sharma 1962, pp. 353–354.

- ^ Kulandran & Hendrik 2004, pp. 177–179.

- ^ Jones & Ryan 2006, p. 266; Sarma 2000, pp. 19–21

- ^ Jones & Ryan 2006, p. 266; Sharma 1962, pp. 417–424; Sharma 1994, p. 373

- ^ Sharma 1994, pp. 374–375; Bryant 2007, pp. 361–362

- ^ Sharma 1994, p. 374.

- ^ Nicholson 2010, p. 157; 229 note 57.

- ^ a b c d e f Nakamura 2004, p. 3.

- ^ a b Nakamura 1989, p. 436. "... we can take it that 400-450 is the period during which the Brahma-sūtra was compiled in its extant form."

- ^ Lochtefeld 2000, p. 746; Nakamura 1949, p. 436

- ^ Balasubramanian 2000, p. xxxiii.

- ^ a b Sharma 1996, pp. 124–125.

- ^ Nakamura 2004, p. 3; Sharma 1996, pp. 124–125

- ^ Hiriyanna 2008, pp. 19, 21–25, 151–152; Sharma 1994, pp. 239–241; Nicholson 2010, p. 26

- ^ Chatterjee & Dutta 2007, p. 317.

- ^ Sharma 2009, pp. 239–241.

- ^ "Historical Development of Indian Philosophy". Britannica.

- ^ Lochtefeld 2000, p. 746.

- ^ a b Nakamura 1949, p. 436.

- ^ Isaeva 1992, p. 36.

- ^ Hiriyanna 2008, pp. 151–152.

- ^ Nicholson 2010, pp. 26–27; Mohanty & Wharton 2011

- ^ Nakamura 2004, p. 426.

- ^ a b Roodurmum 2002, p. [page needed].

- ^ Comans 2000, p. 163; Jagannathan 2011

- ^ Comans 2000, pp. 2, 163.

- ^ Sharma 1994, p. 239.

- ^ Olivelle 1992, pp. 17–18; Rigopoulos 1998, pp. 62–63; Phillips 1995, p. 332 with note 68

- ^ Olivelle 1992, pp. x–xi, 8–18; Sprockhoff 1976, pp. 277–294, 319–377

- ^ Olivelle 1992, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Sharma 1994, p. 239; Nikhilananda 2008, pp. 203–206; Nakamura 2004, p. 308; Sharma 1994, p. 239

- ^ a b c Nikhilananda 2008, pp. 203–206.

- ^ Sharma 2000, p. 64.

- ^ a b Sharma 1994, pp. 239–241, 372–375.

- ^ Raju 1992, p. 175-176.

- ^ Sharma 1994, p. 340.

- ^ Mohanty & Wharton 2011.

- ^ Smith 1976, pp. 143–156.

- ^ Schomer & McLeod 1987, pp. 1–5.

- ^ Gupta & Valpey 2013, pp. 2–10.

- ^ Bartley 2013, pp. 1–4, 52–53, 79.

- ^ Beck 2012, p. 6.

- ^ Jackson 1992; Jackson 1991; Hawley 2015, pp. 304–310.

- ^ Bartley 2013, p. 1-4.

- ^ Sullivan 2001, p. 239; Schultz 1981, pp. 81–84; Bartley 2013, pp. 1–2; Carman 1974, p. 24

- ^ Olivelle 1992, pp. 10–11, 17–18; Bartley 2013, pp. 1–4, 52–53, 79

- ^ Carman 1994, pp. 82–87 with footnotes.

- ^ Bernard 1947, pp. 9–12; Sydnor 2012, pp. 0–11, 20–22

- ^ Fowler 2002, p. 288.

- ^ Bryant 2007, pp. 12–13, 359–361; Sharma 2000, pp. 77–78

- ^ Jones & Ryan 2006, p. 266.

- ^ Bernard 1947, pp. 9–12.

- ^ Hiriyanna 2008, p. 187.

- ^ Sheridan 1991, p. 117.

- ^ von Dehsen 1999, p. 118.

- ^ Sharma 2000, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Sharma 1962, pp. 128–129, 180–181; Sharma 1994, pp. 150–151, 372, 433–434; Sharma 2000, pp. 80–81

- ^ a b Sharma 1994, pp. 372–375.

- ^ a b Hiriyanna 2008, pp. 188–189.

- ^ Lochtefeld 2000, p. 396; Stoker 2011

- ^ Delmonico, Neal (4 April 2004). "Caitanya Vais.n. avism and the Holy Names" (PDF). Bhajan Kutir. Retrieved 2017-05-29.

- ^ a b Kim 2005.

- ^ a b Gajendragadkar 1966.

- ^ Aksharananddas & Bhadreshdas 2016, p. [page needed].

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 3.

- ^ Swaminarayan's teachings, p. 40.[full citation needed]

- ^ King 1999, p. 135; Flood 1996, p. 258; King 2002, p. 93

- ^ King 1999, pp. 187, 135–142.

- ^ King 2002, p. 118.

- ^ King 1999, p. 137.

- ^ Halbfass 2007, p. 307.

- ^ King 2002, p. 135.

- ^ King 1999, p. 138.

- ^ King 1999, pp. 133–136.

- ^ King 2002, pp. 135–142.

- ^ von Dense 1999, p. 191.

- ^ Mukerji 1983.

- ^ Burley 2007, p. 34.

- ^ Lorenzen 2006, p. 24–33.

- ^ Lorenzen 2006, p. 27.

- ^ Lorenzen 2006, p. 26–27.

- ^ Witz 1998, p. 11; Schuon 1975, p. 91

- ^ Clooney 2000, pp. 96–107.

- ^ Brooks 1990, pp. 20–22, 77–79; Nakamura 2004, p. 3

- ^ Carman & Narayanan 1989, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Neog 1980, pp. 243–244.

- ^ Smith 2003, pp. 126–128; Klostermaier 1984, pp. 177–178

- ^ Davis 2014, p. 167 note 21; Dyczkowski 1989, pp. 43–44

- ^ Vasugupta 2012, pp. 252, 259; Flood 1996, pp. 162–167

- ^ Manninezhath 1993, pp. xv, 31.

- ^ McDaniel 2004, pp. 89–91; Brooks 1990, pp. 35–39; Mahony 1997, p. 274 with note 73

- ^ Renard 2010, pp. 177–178.

- ^ Schopenhauer 1966, p. [page needed].

- ^ Jones 1801, p. 164.

- ^ Renard 2010, p. 183-184.

- ^ Iţu 2007.

- ^ Goldstucker 1879, p. 32.

- ^ Muller 2003, p. 123.

- ^ Blavatsky 1982, pp. 308–310.

Sources[edit]

Printed sources[edit]

- Ādidevānanda, Swami (2014). Śrī Rāmānuja GĪTĀ Bhāșya, with Text and English translation. Chennai: Sri Ramakrishna Math, Mylapore, Chennai. ISBN 9788178235189.

- Aksharananddas, Sadhu; Bhadreshdas, Sadhu (2016). Swaminarayan's Brahmajnana as Aksarabrahma-Parabrahma-Darsanam. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199463749.003.0011. ISBN 9780199086573.

- Balasubramanian, R. (2000). "Introduction". In Chattopadhyana (ed.). History of Science, Philosophy and Culture in Indian Civilization. Volume II Part 2: Advaita Vedanta. Delhi: Centre for Studies in Civilizations.

- Bartley, C.J. (2013). The Theology of Ramanuja : Realism and Religion. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-85306-7.

- Beck, Guy L. (2005), "Krishna as Loving Husband of God", Alternative Krishnas: Regional and Vernacular Variations on a Hindu Deity, ISBN 978-0-7914-6415-1

- Beck, Guy L. (2012), Alternative Krishnas: Regional and Vernacular Variations on a Hindu Deity, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-8341-1

- Bernard, Theos (1947). Hindu Philosophy. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1373-1.

- Betty, Stafford (2010). "Dvaita, Advaita, and Viśiṣṭādvaita: Contrasting Views of Mokṣa". Asian Philosophy. 20 (2): 215–224. doi:10.1080/09552367.2010.484955. S2CID 144372321.

- Bhawuk, D.P.S. (2011). Anthony Marsella (ed.). Spirituality and Indian Psychology. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4419-8109-7.

- Blavatsky, H.P. (1982). Collected Writings. Vol. 13. Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publ. House. ISBN 978-0835602297.

- Brahmbhatt, Arun (2016), "The Swaminarayan Commentarial Tradition", in Williams, Raymond Brady; Yogi Trivedi (eds.), Swaminarayan Hinduism: Tradition, Adaptation, and Identity, Oxford University Press

- Brooks, Douglas Renfrew (1990). The Secret of the Three Cities. State University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-22607-569-3.

- Bryant, Edwin (2007). Krishna : A Sourcebook. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195148923.

- Burley, Mikel (2007). Classical Samkhya and Yoga: An Indian Metaphysics of Experience. Taylor & Francis.

- Carman, John B. (1994). Majesty and Meekness: A Comparative Study of Contrast and Harmony in the Concept of God. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0802806932.

- Carman, John B. (1974). The Theology of Rāmānuja: An essay in inter-religious understanding. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300015218.

- Carman, John; Narayanan, Vasudha (1989). The Tamil Veda: Pillan's Interpretation of the Tiruvaymoli. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-09306-2.

- Chari, S. M. Srinivasa (2004) [1988]. Fundamentals of Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedanta (Corr. ed.). Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0266-7.

- Chari, S. M. Srinivasa (1988). Fundamentals of Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedanta. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0266-7. OCLC 463617682.

- Chatterjee, Satischandra; Dutta, Shirendramohan (2007) [1939]. An Introduction to Indian Philosophy (Reprint ed.). Rupa Publications India. ISBN 978-81-291-1195-1.

- Clayton, John (2006). Religions, Reasons and Gods: Essays in Cross-cultural Philosophy of Religion. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-45926-6.

- Clooney, Francis X. (2000). Ultimate Realities: A Volume in the Comparative Religious Ideas Project. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-79144-775-8.

- Comans, Michael (1996). "Śankara and the Prasankhyanavada". Journal of Indian Philosophy. 24 (1). doi:10.1007/bf00219276. S2CID 170656129.

- Comans, Michael (2000). The Method of Early Advaita Vedānta: A Study of Gauḍapāda, Śaṅkara, Sureśvara, and Padmapāda. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1722-7.

- Cornille, Catherine (2019). "Is all Hindu theology comparative theology?". Harvard Theological Review. 112 (1): 126–132. doi:10.1017/S0017816018000378. ISSN 0017-8160. S2CID 166549059.

- Craig, Edward (2000). Concise Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415223645.

- Dandekar, R. (1987), "Vedanta", MacMillan Encyclopedia of religion

- Das, A.C. (1952). "Brahman and Māyā in Advaita Metaphysics". Philosophy East and West. 2 (2): 144–154. doi:10.2307/1397304. JSTOR 1397304.

- Dasgupta, Surendranath (2012) [1922]. A History of Indian Philosophy. Vol. 1, Philosophy of Buddhist, Jaina and Six Systems of indian thought (Reprint, 7th ed.). Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0412-8.

- Davis, Richard (2014). Ritual in an Oscillating Universe: Worshipping Siva in Medieval India. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691603087.

- von Dehsen, Christian (1999). Philosophers and Religious Leaders. Routledge. ISBN 978-1573561525.

- von Dense, Christian D. (1999). Philosophers and Religious Leaders. Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Deutsch, Eliot; Dalvi, Rohit (2004). The Essential Vedanta: A New Source Book of Advaita Vedanta. World Wisdom, Inc. ISBN 9780941532525.

- Doyle, Sean (2006). Synthesizing the Vedanta: The Theology of Pierre Johanns, S.J. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3-03910-708-7.

- Dyczkowski, Mark (1989). The Canon of the Śaivāgama. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-8120805958.

- Etter, Christopher (2006). A Study of Qualitative Non-Pluralism. iUniverse. ISBN 978-0-595-39312-1.

- Flood, Gavin Dennis (1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge University Press.

- Fowler, Jeaneane D. (2002). Perspectives of Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Hinduism. Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-898723-94-3.

- Gajendragadkar, P. (1966), Supreme Court of India: Sastri Yagnapurushadji And ... vs Muldas Brudardas Vaishya And ... on 14 January, 1966. 1966 AIR 1119, 1966 SCR (3) 242

- Gier, Nicholas F. (2000). Spiritual Titanism: Indian, Chinese, and Western Perspectives. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-4528-0.

- Gier, Nicholas F. (2012). "Overreaching to be different: A critique of Rajiv Malhotra's Being Different". International Journal of Hindu Studies. 16 (3): 259–285. doi:10.1007/s11407-012-9127-x. ISSN 1022-4556. S2CID 144711827.

- Goldstucker, Theodore (1879). Literary Remains of the Late Professor Theodore Goldstucker. London: W. H. Allen & Co.

- Goswāmi, S.D. (1976). Readings in Vedic Literature: The Tradition Speaks for Itself. ISBN 978-0-912776-88-0.

- Grimes, John A. (2006). A Concise Dictionary of Indian Philosophy: Sanskrit Terms Defined in English. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0791430675.

- Grimes, John A. (1990). The Seven Great Untenables: Sapta-vidhā Anupapatti. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0682-5.

- Gupta, Bina (1995). Perceiving in Advaita Vedānta: Epistemological Analysis and Interpretation. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 137–166. ISBN 978-81-208-1296-3.

- Gupta, Ravi M. (2016). Caitanya Vaisnava Philosophy: Tradition, Reason and Devotion. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-17017-4.

- Gupta, Ravi M. (2007). Caitanya Vaisnava Vedanta of Jiva Gosvami's Catursutri tika. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-40548-5.

- Gupta, Ravi; Valpey, Kenneth (2013). The Bhagavata Purana: Sacred Text and Living Tradition. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-14999-0.

- Halbfass, Wilhelm (2007). "Research and reflection: Responses to my respondents. V. Developments and attitudes in Neo-Hinduism; Indian religion, past and present (Responses to Chapters 4 and 5)". In Franco, Eli; Preisendanz, Karin (eds.). Beyond Orientalism: the work of Wilhelm Halbfass and its impact on Indian and cross-cultural studies. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-8120831100.

- Hawley, John Stratton (2015). A Storm of Songs: India and the Idea of the Bhakti Movement. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674187467.

- Hiriyanna, M. (2008) [1948]. The Essentials of Indian Philosophy (Reprint ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1330-4. OCLC 889316366.[verification needed]

—OR—

Raju, P. T. (1972). The Philosophical Traditions of India. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 978-0-8229-1105-0. OCLC 482322. - Indich, William M. (1995). Consciousness in Advaita Vedanta. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1251-2.

- Isaeva, N.V. (1992). Shankara and Indian Philosophy. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-1281-7.

- Isaeva, N.V. (1995). From Early Vedanta to Kashmir Shaivism: Gaudapada, Bhartrhari, and Abhinavagupta. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-2449-0.

- Iţu, Mircia (2007). "Marele Anonim şi cenzura transcendentă la Blaga. Brahman şi māyā la Śaṅkara" [The Great Anonymous and the transcendent censorship at Blaga. Brahman and māyā at Śaṅkara]. Caiete Critice (in Romanian). Bucharest. 6–7 (236–237): 75–83. ISSN 1220-6350..

- Jackson, W.J. (1992), "A Life Becomes a Legend: Sri Tyagaraja as Exemplar", Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 60 (4): 717–736, doi:10.1093/jaarel/lx.4.717, JSTOR 1465591

- Jackson, W.J. (1991), Tyagaraja: Life and Lyrics, Oxford University Press, USA

- Jaimini (1999). Mīmāṃsā Sūtras of Jaimini. Translated by Mohan Lal Sandal (Reprint ed.). Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1129-4.

- Jones, Constance; Ryan, James D. (2006). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Infobase Publishing.

- Johnson, W.J. (2009). A Dictionary of Hinduism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198610250.

- Jones, Sir William (1801). "On the Philosophy of the Asiatics". Asiatic Researches. Vol. 4. pp. 157–173.

- Kim, Hanna H. (2005), "Swaminarayan movement", MacMillan Encyclopedia of Religion

- King, Richard (1995). Early Advaita Vedānta and Buddhism: The Mahāyāna Context of the Gauḍapādīya-kārikā. SUNY Press.

- King, Richard (1999). Orientalism and Religion: Post-Colonial Theory, India and "The Mystic East". Routledge.

- King, Richard (2002). Orientalism and Religion: Post-Colonial Theory, India and "The Mystic East". Taylor & Francis e-Library.

- Klostermaier, Klaus K. (1984). Mythologies and Philosophies of Salvation in the Theistic Traditions of India. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 978-0-88920-158-3.

- Koller, John M. (2013). "Shankara". In Meister, Chad; Copan, Paul (eds.). Routledge Companion to Philosophy of Religion. Routledge.

- Kulandran, Sabapathy; Hendrik, Kraemer (2004). Grace in Christianity and Hinduism. ISBN 978-0227172360.

- Lochtefeld, James (2000). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 1: A–M. Rosen Publishing. ISBN 978-0823931798.

- Lipner, Julius J. (1986). The Face of Truth: A Study of Meaning and Metaphysics in the Vedantic Theology of Ramanuja. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-038-0.

- Lorenzen, David N. (2006). Who Invented Hinduism: Essays on Religion in History. Yoda Press. ISBN 9788190227261.

- Mahony, William (1997). The Artful Universe: An Introduction to the Vedic Religious Imagination. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0791435809.

- Malkovsky, B. (2001), The Role of Divine Grace in the Soteriology of Śaṁkarācārya, BRILL

- Manninezhath, Thomas (1993). Harmony of Religions: Vedānta Siddhānta Samarasam of Tāyumānavar. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1001-3.

- Matilal, Bimal Krishna (2015) [2002]. Ganeri, Jonardon (ed.). The Collected Essays of Bimal Krishna Matilal. Vol. 1 (Reprint ed.). New Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-946094-6.

- Matilal, Bimal Krishna (2002). Ganeri, Jonardon (ed.). The Collected Essays of Bimal Krishna Matilal. Vol. 1. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-564436-4.

- Mayeda, Sengaku (2006). A thousand teachings : the Upadeśasāhasrī of Śaṅkara. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-2771-4.

- McDaniel, June (2004). Offering Flowers, Feeding Skulls. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-534713-5.

- Mukerji, Mādhava Bithika (1983). Neo-Vedanta and Modernity. Ashutosh Prakashan Sansthan.

- Muller, F. Max (2003). Three Lectures on the Vedanta Philosophy. Kessinger Publishing.

- Murti, T.R.V. (2008) [1955]. The central philosophy of Buddhism (Reprint ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-46118-4.

- Murti, T.R.V. (1955). The central philosophy of Buddhism. London: Allen & Unwin. OCLC 1070871178.

- Nakamura, Hajime (1990) [1949]. A History of Early Vedānta Philosophy, Part 1 (Reprint ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0651-1.

- Nakamura, Hajime (1989). A History of Early Vedānta Philosophy, Part 1. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0651-1. OCLC 963971598.

- Nakamura, Hajime (1949). A History of Early Vedānta Philosophy. ,[full citation needed]

- Nakamura, Hajime (2004) [1950]. A History of Early Vedānta Philosophy, Part 2 (Reprint ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-8120819634.

- Nicholson, Andrew J. (2010). Unifying Hinduism: Philosophy and Identity in Indian Intellectual History. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-14987-7.

- Nicholson, Andrew J. (2013). Unifying Hinduism: Philosophy and Identity in Indian Intellectual History. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-14987-7.

- Neog, Maheswar (1980). Early History of the Vaiṣṇava Faith and Movement in Assam: Śaṅkaradeva and His Times. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0007-6.

- Nikhilananda, Swami (2008). The Upanishads, A New Translation. Vol. 2. Kolkata: Advaita Ashrama. ISBN 978-81-7505-302-1.

- O'Flaherty, Wendy Doniger (1986). Dreams, Illusion, and Other Realities. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226618555.

- Olivelle, Patrick (1992). The Samnyasa Upanisads: Hindu Scriptures on Asceticism and Renunciation. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-536137-7.

- Pandey, S. L. (2000). "Pre-Sankara Advaita". In Chattopadhyana (ed.). History of Science, Philosophy and Culture in Indian Civilization. Volume II Part 2: Advaita Vedanta. Delhi: Centre for Studies in Civilizations.

- Paramtattvadas, Sadhu (2017). An introduction to Swaminarayan Hindu theology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-15867-2. OCLC 964861190.

- Paramtattvadas, Swami (October–December 2019). "Akshar-Purushottam School of Vedanta". Hinduism Today. Himalayan Academy. Retrieved 2019-11-22.

- Pasricha, Ashu (2008). "The Political Thought of C. Rajagopalachari". Encyclopaedia of Eminent Thinkers. Vol. 15. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 9788180694950.

- Patel, Iva (2018), "Swaminarayan", in Jain, P.; Sherma, R.; Khanna, M. (eds.), Hinduism and Tribal Religions. Encyclopedia of Indian Religions, Encyclopedia of Indian Religions, Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 1–6, doi:10.1007/978-94-024-1036-5_541-1, ISBN 978-94-024-1036-5

- Perrett, Roy W. (2013). Philosophy of Religion: Indian Philosophy. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-70322-6.

- Phillips, Stephen H. (1995). Classical Indian Metaphysics. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0812692983.

- Phillips, Stephen (2000). Perrett, Roy W. (ed.). Epistemology: Indian Philosophy. Vol. 1. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-8153-3609-9.

- Potter, Karl (2002). Presuppositions of India's Philosophies. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0779-2.

- Puligandla, Ramakrishna (1997). Fundamentals of Indian Philosophy. New Delhi: D. K. Printworld.

- Raju, P.T. (1992) [1972]. The Philosophical Traditions of India (Reprint ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

- Rambachan, A. (1991). Accomplishing the Accomplished: Vedas as a Source of Valid Knowledge in Sankara. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1358-1.

- Ramnarace, Vijay (2014), Rādhā-Kṛṣṇa's Vedāntic Debut: Chronology & Rationalisation in the Nimbārka Sampradāya (PDF)

- Renard, Philip (2010). Non-Dualisme. De directe bevrijdingsweg. Cothen: Uitgeverij Juwelenschip.

- Rigopoulos, Antonio (1998). Dattatreya: The Immortal Guru, Yogin, and Avatara. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0791436967.

- Roodurmum, Pulasth Soobah (2002). Bhāmatī and Vivaraṇa Schools of Advaita Vedānta: A Critical Approach. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

- Sarma, Deepak (2005). Epistemologies and the Limitations of Philosophical Enquiry: Doctrine in Madhva Vedanta. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415308052.

- Sarma, Deepak (2000). "Is Jesus a Hindu? S.C. Vasu and Multiple Madhva Misrepresentations". Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies. 13. doi:10.7825/2164-6279.1228.

- Scharfe, Hartmut (2002). Handbook of Oriental Studies. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-12556-8.

- Schomer, Karine; McLeod, W. H., eds. (1987). The Sants: Studies in a Devotional Tradition of India. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 9788120802773.

- Schopenhauer, Arthur (1966). The World as Will and Representation, Vol. 1. Translated by Payne, E.F.J. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0486217611.

- Schultz, Joseph P. (1981). Judaism and the Gentile Faiths: Comparative Studies in Religion. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-1707-6.

- Schuon, Frithjof (1975). "One of the Great Lights of the World". In Mahadevan, T.M.P. (ed.). Spiritual Perspectives, Essays in Mysticism and Metaphysics. Arnold Heinemann. ISBN 978-0892530212.

- Sharma, Arvind (2007). Advaita Vedānta: An Introduction. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-8120820272.

- Sharma, Arvind (2008). Philosophy of religion and Advaita Vedanta: a comparative study in religion and reason. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0271028323. OCLC 759574543.

- Sharma, Chandradhar (2009) [1960]. A Critical Summary of Indian Philosophy. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0365-7. OCLC 884357528.

- Sharma, Chandradhar (1994) [1960]. A Critical Survey of Indian Philosophy (Reprint ed.). Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0365-7.

- Sharma, Chandradhar (2007) [1996]. The Advaita Tradition in Indian Philosophy: A Study of Advaita in Buddhism, Vedānta and Kāshmīra Shaivism (Rev. ed.). Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-8120813120. OCLC 190763026.