사티 (불교)

| 이 문서의 내용은 출처가 분명하지 않습니다. (2016년 7월) |

사티(sati)는 팔리어 불교 용어로 통상 팔정도의 정념(正念, sammā-sati)을 가리킨다고 해석될 수 있다. 사띠, 싸띠라고도 발음한다. 서양에서는 사티를 Mindfulness라고 부르는 경우가 존재하는데, 한국에서 Mindfulness를 마음챙김이라 번역하는 경우와 함께 생각하면 사티는 곧 마음챙김과 동의어라 인식될 수 있다. 이에 대해 다양한 의견이 존재할 수 있다.

팔정도[편집]

석가모니는 외도의 선정수행과 고행을 바른 수행이 아니라고 보았는데, 그 수행법에는 선정이 있지만 정념(正念, sammā-sati)이 없다는 것이 핵심이다. 정념이 없는 선정(사마디)은 삼마사마디(sammā-samādhi) 즉 팔정도의 정정(正定)이 아니다.

아나파나사띠[편집]

석가모니는 아나파나사띠 수타에서 아나파나사띠를 가르쳤다. 마음으로 다섯을 세며(사띠) 짧게 숨을 들이쉬고(아나), 마음으로 다섯을 세며(사띠) 길게 숨을 내쉰다(파나). 숨이 바뀔 때 넷이 되어도 여섯이 되어도 안된다. 따라서 고도의 정신집중(사띠)가 필요하다. 이러한 숨을 세는 명상이 익숙해지면, 모든 번뇌를 벗어나 누진통을 이루어 부처가 된다고, 아나파나사띠 수타에서 석가모니가 가르친다. 그밖에도 수많은 정신수행상의 효능을 아나파나사띠 수타에서 설명한다.

간화선[편집]

12세기 중국 임제종 대혜종고 스님이 만든 명상법인 간화선에서, 사띠는 화두를 의심하는 마음상태를 말한다.

마음챙김[편집]

서양판 사띠 명상법인 마음챙김 명상법이 유명해진 것은 1979년 MBSR(Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction) 프로그램을 개발한 매사추세츠 대학교 의과대학의 존 카밧 진 교수(en:Jon Kabat-Zinn) 때문이다. 1974년 한국 숭산 스님(1927~2004)의 제자가 되어 한국의 참선을 배웠으며, 역시 숭산 스님이 설립한 보스턴 근교의 케임브리지선원(en:Cambridge Zen Center)의 수석법사로 참선을 지도했다.

같이 보기[편집]

- 마음챙김 - 사띠 명상법이 서양에서 발전하여 마음챙김 명상법이 되었다.

마인드 플루네스

Mindfulness ( 영혼 : mindfulness )는 현재 일어나고있는 경험에주의를 기울이는 심리적 과정입니다 [1] [2] [3] . 명상 및 기타 훈련을 통해 발달시킬 수 있다고 여겨진다 [2] [4] [5] .

어의로서 「지금 이 순간의 체험에 의도적으로 의식을 향해, 평가를 하지 않고 잡히지 않는 상태로, 단지 보는 것」이라고 하는 설명이 이루어지는 일도 있다 [6] . 그러나, 특히 새로운 사고방식이 아니라, 동양에서는 명상의 형태로의 실천이 3000년 있어, 불교적인 명상에 유래한다 [7] .

현재의 마인드플루네스라고 불리는 언설이나 활동, 조류에는, 상좌부 불교 의 용어의 번역어로서의 마인드플루네스가 있어, 이 불교 본래의 마인드플루네스에서는, 달성해야 할 특정한 목표를 가지지 않고 실천 된다 [8] [9] . 의료 행위로서의 마인드플루니스는, 여기에서 파생되어 미국에서 태어난 것으로, 특정의 달성해야 할 목표로 행해진다 [8] [9] . 마음가짐은 크게 이 두 흐름으로 나뉜다 [8] .

의료 행위로서의 마인드플루니스는, 1979년에 존 카바트 진이 , 심리학의 주의의 초점화 이론과 조합해, 임상적인 기법으로서 체계화했다 [7] . 마음을 편안하게 하거나, 깨끗하게 하거나, 사고를 통제하거나, 불편함을 즉각 해결하는 것은 아니다 [10] .

개요 [ 편집 ]

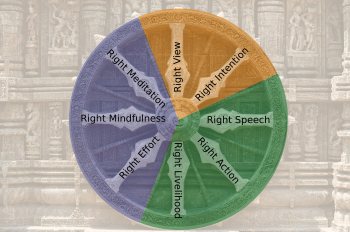

마인드풀네스(mindfulness)라는 용어는 불교의 중요한 가르침인 중도 의 구체적 내용으로 묘사되는 팔정도 중 제7지에 해당하는 파리어 의 불교 용어 산마 사티 (Samma-Sati, 한어: 정념, 옳은 마인드풀네스)의 사티의 영역이다 [11] [12] . 삼마 사티는 "항상 침착 한 마음의 행동 (상태)"을 의미한다 [13] . 사티는 일부 불교 의 전통에서 중요한 요소이다 [14] [15] .

불교에서 팔정도로 설교되는 8개의 가르침은 서로 유기적으로 연관된 하나의 수행 시스템이며, 독립적으로 행해지는 것은 상정되지 않는다. 팔정도에 의해 「분리한 자아」, 고립적으로 존재하는 실체적 존재로서의 자아라고 하는(불교에 있어서) 잘못된 인식을 해체해( 무아 ), 모두가 서로 연결되어 생기고 있다( 연기 ) 라고 하는 올바른 인식에 근거해 살 수 있게 된다고 생각되어 정념도 이 비전에 근거해 이해되고 실천되었다 [12] [16] . 정념은, 사람을 고통 으로부터의 완전한 해방이나 깨달음 이라고 불리는 것에 서서히 이끌어 가는 자기 인식이나 지혜 를 발달시키는 데 도움이 되어 「무아」나 「무상」이라는 진리를 깨닫고 해탈에 이르기 위한 방법으로 실천되어 왔다 [14] [16] .

최근의 서양에서의 마인드플루네스의 유행은 1965년에 미국에서 이민국적법 이 성립되어 아시아로부터의 이민이 증가한 것을 배경으로 독일에서 태어난 스리랑카 상좌부 불교 스님 냐나포니카 테라 와 베트남인 선승 티크 너트 한과 같은 승려들이, 마인드풀네스가 불교의 중심이라고 설해, 영어로 마인드풀네스에 관한 저작을 많이 쓴 것으로 시작된다 [8] [17] . 의료로서의 마인드플루네스는 선 을 배운 미국인 분자생물학자인 존 카바트 진이 1979년 매사추세츠 대학 에서 불교색을 배제하고 현대적으로 어레인지한 마인드플루네스 스트레스 저감법 (MBSR) [18] [17] [19] [20] , 이 새로운 정신 요법의 기본 이념은 도모젠 선사 의 조동종 이었다 [21]. 서양에는 불교적인 전제가 없는지, 꽤 희박했던 적도 있어, 마인드플루네스는 불교의 문맥이나 진리와의 관계, 팔정도의 처음에 놓여 수행의 방향성의 지침이 되는 정견 (불교의 진리인 사기 (고·집·멸·길)나 십이연기 의 현법 등을 자각하는 올바른 견해, 올바른 비전)과도 분리되어 “단체의 주의의 스킬”로서 받아들여 전개했다 [22] [23] [13] [16] . 서양의 세속적인 마인드플루니스는 '나'를 중심으로 정한 자기수양, 자기성취, 자기증진을 위한 것으로 이해되고 실천되고 있다 [24] . MBSR은 당초만큼 주목받지 않았고, 행동요법 의 일환으로 보급되어 갔다 [13] . 명상 연구는 1980년대 이후 세계적으로 침체가 계속되고 있었다 [13] .

2000년대에 들어서면 미국에서는 동양의 사상실천에 대한 흥미가 높아지고, 미국 현대사회가 부족한 「『지금』에의 집중」이 불교의 사상실천에 보인다고 생각되어, 마인드풀네스 명상이 다시 한번 주목받게 되었다 [13] . 냐나포니카 테라에서 시작되는 조류 아래, 오늘날 많은 연구자들이 마인드플루네스 명상이란 '깨달음'이나 '있는 그대로의 주의'를 중시하는 '통찰 명상'이며, 비파사나 명상 과 보보 동의로 있다고 본다 [17] . 심리적·신체적 건강과 양호한 인간관계, 냉정한 의사결정, 일이나 학업에의 집중, 전반적인 생활의 향상 등에 효과가 있다고 주목을 받고 있다 [17] .

일본에서는, 1993년에 개최된 워크숍은 그다지 관심을 모으지 않았지만, 2016년에 NHK에서 스트레스의 대처 기법으로서 특집이 복수회 방송되는 등, 최근 미디어에서 거론될 기회가 증가했다 . ] [25] . 2016년 후반에는 Apple사의 스마트폰 'iPhone'에서 헬스케어 앱에 '마인드플루네스' 카테고리가 추가되는 등 급속히 일반적으로 침투하고 있다 . 이에 따라 비즈니스화도 진행되어, 마인드후루네스의 명칭을 이용해, 본래의 마인드후루네스와 멀리 떨어진 끔찍한 것도 나돌고 있다 [25] .

반대로 우울증 과 걱정 은 우울증 과 불안 과 같은 정신 질환 을 일으키는 원인이 될 수 있지만 [26] [3] , 마음의 근거에 기초한 의학적 개입 은 반대로 우울증과 걱정을 줄이는 데 효과적입니다. 여러 연구가 보여준다 [26] [27] .

1970 년대 이래 임상 심리학과 정신의학 은 다양한 심리적 상태를 경험하고 있는 사람들을 돕기 위해 마인드플루니스에 기초한 많은 치료 응용을 개발해 왔다 [20] . 예를 들어, 마음 풍성의 실천은 우울증의 증상을 완화하거나 [28] [29] [30] , 스트레스 [29] [31] [32] 와 걱정을 줄이는 것 [28] [29] [32] , 약물 의존 에 대한 수당에 사용되어 왔다 [33] [34] [35] . 또한 정신병 환자에 대한 많은 치료 효과도 제시 하고 [36] [37] , 심장 건강에 관한 문제를 멈추기 위한 예방적인 방책이 되고 있다 [38] .

여러 환자 범주와 건강한 성인 및 어린이의 신체적 건강과 정신 건강의 양면에 대한 마인드 플루 니스의 효과를 여러 임상 연구 가 기록했다 [3] [39] [40] . 존 카바트 진에 의한 프로그램과 그와 유사한 방식의 프로그램은 학교, 형무소 , 병원, 퇴역군인 센터 등에 널리 채용되고 있다. Mindfulness 프로그램은 건강한 노화, 체중 관리, 운동 능력 향상, 특별한 요구를 가진 어린이 지원, 주산기 개입 등에도 적용되고 있다. 이 분야에서 보다 양질의 학술연구를 위해서는 보다 많은 무작위화 비교연구 와 연구에 있어서의 방법론의 세부사항을 제공하고, 보다 큰 표본수 의 사용이 필요하다 [3] [41] .

명상 [ 편집 ]

Mindfulness 명상 은 현재 현재 일어나고있는 일에주의를 기울이는 능력을 개발하는 과정을 포함합니다 [2] [14] [42] . 임상 적으로 디자인 된 세속적 인 마음 가루는 두 가지가 특히 강조되어 있다 . non-judgmental은 심리 요법에서 '탈중심화'라고 불리는 자신의 체험으로부터 조금 거리를 두거나 공간을 만드는 기법에 통하는 것이 있으며, 마인드플루니스의 효과는 주로 이 특성에 따른다고 생각 된다 [43] . present-centered 는, non-judgmental인 「being 있는 것」모드와 judgmental인 「doing 하는」모드의 대비로서 설명되는 경우가 많고, 현재의 순간을 중심으로 두는 것으로, 과거나 미래에의 관련 에서의 평가를 그만두고 지금 현재 일어나고 있는 것에 주의를 돌린다 [43] . Mindfulness는 말하자면 doing 모드에서 being 모드로 기어를 시프트하는 것으로 여겨지며, 걱정에 사로 잡혀 현재의 순간에서 벗어나 자신의 가고있는 일이나 경험하고있는 것에 무자각한 채 「자동 조종 상태」에 빠져 버리는 것에 대한 매우 유효한 대책으로 생각되고 있다 [43] .

마인드풀네스 명상을 하기 위해 설계된 명상 운동이 몇 가지 있다. 그 중 하나는 등받이가 똑바른 의자에 앉거나 바닥이나 쿠션 위에 다리를 짚고 앉아 눈을 감고 숨이 들어가거나 나올 때의 감각 에 주의를 돌리는 방법이다. 그 때에 주의를 돌리는 대상은, 콧구멍 근처에서의 호흡 의 감각, 또는 복부 의 움직임의 어느 쪽인가로 한다 [44] [45] [1] . 이 명상 실천에서는, 실천자는 호흡을 통제하려고 하지 않고, 자신의 자연스러운 호흡의 프로세스나 리듬에 단지 눈치채고 있는 것을 시도한다 [2] . 이것을 하고 있을 때, 마음이 사고나 연상 으로 흘러가는 것이 자주 일어난다. 그것이 일어났을 경우, 실천자는, 주의가 산만하게 되고 있는 것에 수동적으로 눈치채고, 치우친 개인적인 판단을 하지 않고 수용적인 방법으로, 주의를 호흡에 되돌린다.

마인드풀네스를 발달시키는 다른 명상 운동으로는, 신체 의 여러가지 장소에 주의를 돌려, 그 때 일어나고 있는 신체의 감각을 깨닫는다 보디스캔 명상이 있다 [2] [1] . 요가 에서 움직임이나 신체감각에 주의를 돌리거나 걷는 명상(워킹 메디테이션)을 하는 것도, 마인드플루니스를 발달시키는 방법이 된다 [2] [1] . 지금 현재 일어나고 있는 소리 , 감각, 사고, 감정 , 동작 등에 주의를 돌릴 수도 있다 [2] [42] . 이 점에서 유명한 운동은 존 카바트 진이 마인드플루네스 스트레스 저감법 의 프로그램으로 도입한, 건포도 를 마인드풀로 맛보 는 것이다 .[46] 있다 [47] [주석 1] .

명상자는 하루에 10분 정도의 짧은 시간에 명상을 시작하도록 권장된다. 정기적으로 실천함에 따라 호흡에 대한 주의를 유지하는 것이 용이해진다 [2] [48] .

번역 및 정의 [ 편집 ]

Mindfulness 명상 은 다양하게 정의 될 수 있으며 다양한 목적으로 사용될 수 있습니다. 마음 충성 명상을 정의 할 때, 불교 의 심리학 전통과 경험적 심리학 에서 발전하는 지식을 사용하는 것이 유리합니다 [14] [49] [50] .

다만, 현재의 마인드플루네스 명상은, 불교 경전을 직접적인 배경으로서 태어난 것은 아니다 [17] . 마인드풀네스라고 불리는 불교 명상 이 서양 으로 퍼지는 계기가 된 독일인으로 테일러 와다 불교의 스님 냐나포니카 테라 (1901 - 1994) 의 핵심이지만, 정념 그 자체가 아니고, 「최소한의 그대로의 주의」(bare attention)이며, 전혀 신비적인 것은 아니다고 했다 [17] . 이후 서양에서는 마인드플루네스란 「있는 그대로의 주의」라는 견해가 퍼져 불교 명상의 많은 저작에서도 이 의미로 사용되게 되었다 [17] .

불교의 어의 [ 편집 ]

sati와 smṛti [ 편집 ]

이 절의 가필 이 바람직합니다. |

mindfulness [주석 2] 로 영어 번역된 불교 용어는 파리어 의 sati( 사티 ) 및 산스크리트 에서 sati에 해당하는 smṛti에 기원이 있다. Robert Sharf에 따르면 이러한 단어의 의미는 광범위한 토론과 토론의 주제가되었습니다 [53] . 원래 smṛti는 to remember(기억, 기억 하고 있다 [54] ), to recollect(회상, 회상한다 [55] ), to bear in mind(심지어 두는 [56] )를 의미했다. sati도 to remember를 의미한다. 대념 처경 (역자 주 : 또는 염처경 )에서 sati는 불교의 법 을 기억 / 기억한다는 것을 의미하며, 이에 따라 수행자는 다양한 현상의 본질 을 볼 수있다 [53] . “사티가 생기는 것은 사념처 , 오네 , 오력 , 칠각지, 팔정도 등 의 건전한 제법 을 마음에 불러일으킨다”라고 설명하고 있는 「밀린다 왕의 질문」을 Sharf는 참조하고 있다 [57] .

번역 [ 편집 ]

mindfulness의 의미를 일반적으로 파악하면 매우 모호하고, 이것이 마인드후루네스라는 단어의 이해하기 어려움으로 연결되어있다 [58] . 영어로서 일상적으로는 「주의로 가득한」 「주의로 가득한 상태」라는 의미로 사용되고 있어, 심리학에서도 주의와 결합해, 「충분한 주의」를 나타내는 것으로 생각된다 [59] . mindful이라는 형용사는 '잘 기억하고 있는 것'이라는 뜻으로 14세기 중반부터 사용되며, 점차 '마음을 남겨둔다', '마음을 나눠', '깨닫는다'라는 의미도 가지게 되고, 16세기에 철자는 다르지만, 명사로서 사용되게 되었다 [60] . 그러나 본 기사의 의미의 마인드플루니스는 원래 영어에 있던 mindful에서 태어난 말이 아니라, 19세기에 불교 용어를 영어로 번역할 때 맞는 것이고, 점차 전문적인 의미가 추가해 일반적으로 퍼졌다. 그 때문에 본 기사의 의미에서의 mindfulness 는, 영어권에서도 2000년경의 단계에서는, 전문가 이외에는 그다지 알려지지 않았던 것 같다 [61] .

1845년 , Daniel John Gogerly 가 sammā-sati를 Correct meditation(올바른 명상 [62] [63] )으로 처음으로 영역했다 [64] .

1881년 에 원시 불교의 경전에 사용되고 있는 파리어 의 학자인 토마스 윌리엄 리스 데이비즈 가, 팔정도에서의 sammā-sati를 Right Mindfulness(the active, watchful mind)라고 번역한 것이, sati 가 mindfulness 로 영어로 번역된 첫번째이다 [65] [61] . 사티는 "마음을 그대로 두는 것, 혹은 마음에 머물러있는 상태로서의 기억, 마음에 머물렀던 것을 부르는 기억의 일, 마음에 머무는 일로서의 주의력"이며, 이 '마음을 남겨둔다', '주의' 등의 의미가 영어의 mindfulness의 함의와 가까웠기 때문에, 영역으로 선택되어, mindfulness가 불교적인 의미를 띠게 되었다 [61] .

데이비즈는 1881년에 다음과 같이 설명하고 있다.

기타 번역 [ 편집 ]

John D. Dunne 은 sati와 smṛti를 mindfulness로 번역하는 것은 혼란스럽다고 강력하게 주장합니다. 몇몇 불교 학자 들은 “retention”을 보다 바람직한 번역으로 확립하려고 시도하고 있다 [67] [ 출처 무효 ] . Bhikkhu Bodhi 도 sati의 의미는 memory (기억, 기억력 [68] )라고 지적한다 [69] [주석 3] .

sati나 smṛti에는 다음과 같은 영역이 있다 [ 요출전 ] .

- Attention ( Jack Kornfield ) - 주의 , 고려, 고려, 수당, 돌보기 [70]

- Awareness - 알고 있는 것, 자각, 의식 [71] . 착용감 .

- Concentrated attention ( 마하시 사야도 )

- Inspection ( Herbert V. Günther ) - 검사, 사찰, 시찰 [72]

- 주의 집중

- Mindfulness - 주의, 잊지 말고, 유혹, 조심 [52]

- 마음챙김의 회상( Alexander Berzin )

- Recollection ( Erik Pema Kunsang , 푸타타트 ) - 기억, 기억, 기억력 [55]

- Reflective awareness (푸타타트)

- 상기시키기( 제임스 H. 오스틴 ) [73]

- Retention - 기억, 기억력, 보유, 보존, 지속, 계속 [74]

- 자기 회상(잭 콘필드)

심리학 [ 편집 ]

이 절의 가필 이 바람직합니다. |

기타 용법 [ 편집 ]

영어의 "mindfulness"라는 단어는 불교의 맥락에서 사용되기 이전부터 존재했습니다. 1530년 에 John Palsgrave 가 프랑스어 의 “pensée”를 “myndfulness”로 한 것이 최초의 기록이었고, 1561년 에는 “mindfulnesse”로 되어, 1817년 에 “mindfulness”로 되었다. 형태 론적 으로 더 빠른 단어는 "mindful"( 1340 년 ), "mindfully"( 1382 ), 그리고 지금은 사용되지 않는 "mindiness"( 1200 년경 )를 포함합니다 [75] .

웹스터 사전 에 따르면, mindfulness는 "a state of being aware"(알고 있는 상태 [76] [77] [78] )를 가리킨다 [79] . 이 "state of being aware"의 동의어는 wakefulness [80] [81] (조심스럽고 방심하지 않는 것 [82] ), attention [83] ( 주의 , 고려, 배려, 수당, 돌보는 [70] ), alertness [84] (방심, 주의, 민첩 [85] ), prudence [84] (분별, 사려, 준비 주도 [86] ), conscientiousness [84] (양심적, 정직, 성실 [87 ) ] ), awareness [79] (알고 있는 것, 자각, 의식 [88] , 착용 )[79] (의식, 지각 , 자각 [89] ), observation [79] (관찰, 관찰력, 관측, 눈, 감시 [90] ) 등이다.

역사 [ 편집 ]

불교 [ 편집 ]

현대적인 서양 의 실천으로서의 마인드플루니스는 현대의 [주석 4] 비파사나 명상 과 사티 의 훈련에 기초하고 있다. 이 사티는 「현재의 사건에 대한, 그 순간마다의 깨달음」을 의미할 뿐만 아니라, 「물건을 눈치채는 것을 잊지 말고 있다」라고 하는 것을도 의미하고 있다 [93] . 오늘날, 많은 연구자들은 Mindfulness 명상이 Vipassana 명상 과 보보 동의로 간주됩니다 [17] .

비파사나 명상과 사티는 사람을 실재의 본질 즉 삼상 으로 이끄는 지혜 를 가져온다. 삼상이란, 무조건 , 조건부된 모든 존재의 고통 , 무아 이다 [14] . 불교 수행자는 삼상을 통찰함으로써 '흐름에 들어간 자'라는 의미의 예류 라는 상태가 된다. 예류는 사향사과 의 첫 단계이다 [94] [95] . 비파사나 명상은 사마타 명상 과 함께 실천되어 불교의 전통에서 중심적인 역할을 한다 [96] .

Paul Williams 는 Erich Frauwallner 를 참조하여 초기 불교 에서 마인드 플루네스가 해탈 의 길을 제공했다고 합니다 . 을 멈추기 위해서, 감각 상의 경험을 항상 주의해서 보는 것"이라고 말하고 있다 [97] [주석 5] . Tilman Vetter에 의하면, 선정 (梵: dhyāna )은 부처 의 수행의 핵심 요소였을지도 모른다. 선정은 마음가짐의 지속을 돕는다 [98] .

리스 데이비즈 에 의하면, 마인드플루네스의 교리는, 사망 과 팔정도 에 이어 「아마 가장 중요한 것」이라고 한다. (데비즈는 부다의 가르침을 자기 실현 을 위한 합리적인 기법으로 여겼고, 그 가르침의 일부(주로 환생의 교리)를 설명할 수 없는 미신 으로 거부했다 [99] .)

오늘의 마인드 플루네스의 기본 문헌으로, 파리 불전 "아너 파나 사티 스타 ( 안반 염경 ) " 수행자를 위한 가르침의 구체적인 실천을 설교한 안내서이기 때문에 왜 그러한 실천을 하는지, 어떤 방향성으로 실천을 하는지, 그 결과 어떻게 된 일이 일어날 수 있는지 등 불교적 문맥 는 당연히 올바르게 공유되어야 하는 전제로 생략되어 있다 [100] .

초월 [ 편집 ]

이 절의 가필 이 바람직합니다. |

존 카바트 진과 MBSR [ 편집 ]

1979년 , 존 카바트 진 은 만성 질환 을 치료하기 위해 매사추세츠 대학 에서 Mindfulness Stress Restoration Method (MBSR) 프로그램을 만들었다 [101] . 의학에서이 프로그램은 건강한 사람과 건강에 해로운 사람 모두의 다양한 상태를 다루기 위해 마음 풍선의 아이디어를 적용하는 것의 화재를 끊었다 [102] : 230-231 .

마인드풀네스의 실천은 주로 동양 의, 특히 불교 의 전통에 있어서의 가르침으로부터 발상을 얻고 있다. 마인드플루네스 스트레스 저감법을 해설하는 저작으로, 마인드플루네스 명상법은 "아시아의 불교에 뿌리를 둔 명상의 하나의 형식"이라고 소개되고 있다 [18] . 정신과 의사의 가이타니 히사요시 가 카바트 진 본인에게 확인한 바에 따르면, 이 새로운 정신 요법의 기본 이념은 도모토 선사의 조동종 이다 [21] . MBSR의 기법 중 하나인 바디스캔은 버마 의 우 바킨 의 전통에 있어서의 “sweeping”이라는 명상 실천에서 유래하며, 사티아 나라얀 고엔카 가 1976년 에 시작한 비파사나 명상 의 리트리트에서 교수 했다. 바디 스캔은 종교적 맥락과 문화적 맥락에서 독립적인 비종교적인 도구로 널리 채택된다 [주석 6] .

대중화와 마인드풀네스 무브먼트 [ 편집 ]

불교 의 명상 또는 임상 심리학 에의 응용과는 별도로, 일상생활에서 실시하는 실천으로서의 마인드플루니스의 인기가 높아지고 있다 [48] . 마인드플루네스는 인생의 스타일로 볼 수도 있고 [103] , 공식적인 실천환경의 밖에서 할 수도 있다 [104] . 종교 학자 , 과학자 , 언론인 , 대중 매체의 작가 등은 이러한 마음 풍성의 ' 대중화 '와 마음 풍성이 실천되는 새로운 환경이 태어나고 있다는 동향을 표현하기 위해 사용 된 용어는 "마인드 플루네스 운동"입니다. 이 동향은 2016년 까지의 20년간에 발전해 왔으며, 그 사이에 비판도 몇 가지 나타났다 [105] .

치료 프로그램 [ 편집 ]

의료로서의 마인드플루니스는, 미국에서의 불교의 전개를 배경으로 성립했다 [18] . 의료에서의 마인드플루네스의 실천은, 현재 다양한 것이 되고 있지만, 그 베이스에는, 매사추세츠 대학 의학부의 분자 생물학자 존 카바트 진이 개발한 「마인드후루네스스트레스 저감법 (마인드플루네스 ) 근거한 스트레스 감소 방법, mindfulness-basedstressreduction, MBSR)' 및 ' 마인드플루네스 인지 치료 (mindfulness-basedcognitivetherapy, MBCT)'라는 확립된 방법이 있다 [18] .

죤 카바트 진 이른바, 마인드플루네스의 실천은 불교의 전통이나 어휘를 이용하는 것을 염려하지 않는 서양사회의 사람들에게 유익할 수 있다 [106] . 정신건강의 대처 프로그램으로서 채용한 서양의 연구자나 임상의는, 통상 마인드플루네스를, 그 종교적·문화적 전통의 기원과는 다른 것으로 지도하고 있다 [107] . 2013년 현재, MBSR 및 이와 유사한 프로그램은 학교, 감옥 , 병원, 퇴역 군인 센터 등에서 널리 적용되고 있다 [108] .

Mindfulness 스트레스 감소 방법 (MBSR) [ 편집 ]

1979년 존 카바트 진이 매사추세츠 대학의 의료 센터에서 개발한 스트레스 관련 장애, 만성 통증, 고혈압, 두통 등의 증상을 개선하기 위한 프로그램 이다 . 영적인 가르침을 기원으로 하지만, 이 프로그램 자체는 비종교적·세속적인 것이다 [2] . 사람들이 좀 더 마음에 걸릴 수 있도록 건포도 운동, 호흡법, 정좌 명상법, 바디 스캔, 요가 명상법, 보행 명상법, 일상 명상 훈련으로 구성되어 의식적으로 "지금"에 관심을 돌립니다. 태도를 익히기 위한 명상이 기본이다 [7] . 8주간의 프로그램으로, 각 주의 세션은 2시간 반부터 3시간, 30명 정도의 클래스로 실시된다 [7] .

Mindfulness 인지 요법 (MBCT) [ 편집 ]

MBSR 기법과 인지요법 기법을 조합하여 관해기 우울증 환자를 대상으로 개발되었다 [7] . 매주 1회 2시간, 8주 세션에서 우울증을 예방하는 기술을 배웁니다. 클래스 는 12명 정도가 상한이다 .

제3세대의 행동요법이며, 제1세대가 「행동」을 목표로 부적응 행동의 수정을, 제2세대가 「사고」를 목표로 기분이나 감정을 바꾸는 것을 목표로 한 것에 대해, 「 주의를 목표로 기분이나 감정을 바꾸려는 것이다 [109] . 불쾌한 기분이나 감정의 생기를 통제하는 것이 아니라, 무엇에 어떻게 주의를 돌리는지, 거리를 두고 대처하는 방법을 배운다 [109] . 주의 훈련으로서, 마인드플루니스가 도입되고 있다 [109] .

건포도 운동, 바디 스캔, 호흡법, 정좌 명상, 3분간 호흡 공간법, 보행 명상, 인지 요법에 사용되는 「기쁜 일 일지」, 「싫은 일 일지」, 「우울의 구체적 증상의 학습 '등으로 체험의 질을 변화시켜 자신이 자동 조종 상태에 있는 것을 깨달아, '하는 것 모드'에서 '있는 것 모드'로의 전환을 실습해, 호흡에 대한 마인드풀네스를 높여, ' 현재'에 머물러 있는 스킬, 부정적인 감정, 신체감각, 사고 등을 통제하지 않고 그대로 받아들이는 것을 배우고, 사고는 사실이 아니라는 것을 알고, 자신을 소중히 하는 방법 등을 익힌다 [7] .

변증 법적 행동 요법 (DBT) [ 편집 ]

워싱턴 대학의 마샤 리네한 에 의해 경계성 퍼스널리티 장애 의 치료법으로서 개발된 것으로 [110] , 제3세대의 인지 행동요법으로 여겨지는 것의 하나이다 [111] . 섭식 장애 , 기분 장애 , 불안 증상 등에도 유효하다 [110] . 경계성 퍼스널리티 장애를, 감정적으로 상처 받기 쉽고 조정 불량이 되기 쉬운 기질과 「타당성을 평가하지 않는 환경」이 서로 얽혀 있는 것에 의한 악순환으로부터 생기는 감정 조정의 장애라고 생각한다 [110] . 타당성을 평가하지 않는다는 것은 그 사람의 진실인 것, 효과적, 순수한 행동, 사고, 감정, 자기 개념을 부적절하다고 생각하고 벌하거나 비판하는 것이다 110] . 감정, 대인관계, 자기, 행동, 인지라는 그 행동양식의 카테고리 모두를 치료의 대상으로 하고, DBT 전략과 심리사회적 스킬 트레이닝에 의해 치료를 실시한다 [110] . 심리사회적 스킬 트레이닝에는 마인드플루니스가 포함되어 있으며, 그 근간의 스킬에는 각 사람이 마음속에 가지는 지혜인 '현명한 마음'이 있다고 한다 [110] .

수락 및 약속 치료 (ACT) [ 편집 ]

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy(약칭:ACT, 액트)는, 미국의 Steven C. Hayes 등에 의해 2000년경에 시작된 심리 요법으로, 행동적 요법의 흐름을 계승한다 [112] [113] . ACT를, A=accept, C=choose, T=take action(수용할 수 있다―선택한다―실행한다)라고 하는 포착 방법도 있어, 클라이언트는 자신의 고통이나 불안으로부터 도망치지 않고 받아들여 자신을 거기에 노출 (accept), 클라이언트 자신의 욕망이나 기분에 사로잡히지 않고 자신에게 있어서 가치있는 것을 선택하고(choose), 자신이 선택한 것을 실행하는(take action) 것을 목표로 한다 [112] . 실행을 동반하는 적극적인 심리 요법이며, MBSR과 마샤 리네 한의 변증법적 행동 요법 의 영향을 받고 있다. 심리적 유연성 을 창출하기 위해, 수용 또는 마인드플루니스 과정이 이용된다 [113] .

행동치료는 행동을 바꾸고, 인지요법은 인지를 바꾸는 것을 강조하지만, ACT는 행동이나 인지(사고)를 변용시키는 것이 아니라, 그대로 받아들여지는 것을 강조한다 [112] . 소노다 준이치 등은 정신병리를 파악하는 방법, 치료과정이 일본에서 독자적으로 발전한 모리타 요법 과 매우 비슷하다고 지적하고 있다 . [112 ]

Mode deactivation therapy(MDT) [ 편집 ]

이 절의 가필 이 바람직합니다. |

기타 프로그램 [ 편집 ]

이 절의 가필 이 바람직합니다. |

모리타 요법 [ 편집 ]

모리타 요법 은 일본에서 1919년(타이쇼 8년)에 탄생하여 발전한 심리 요법이다 [114] . 창시자의 모리타 마사마는 , 「고를 고통으로 맡아 오히려 그것이 되고 끊어졌을 때에, 편이 보인다」라고 하고 있어, 이렇게 「있는 그대로」를 핵심으로 하는 것이, 마인드후루네스 를 연상시킨다고 한다 [115] [116] . 모리타 요법 연구소 소장의 의사北西憲二는 모리타 요법은 마인드플루네스의 사상도 포함한 보다 큰 지식이며, 정적인 마인드플루네스보다 역동적인 것이라고 말하고 있다 [117] [116] .

과학 연구 [ 편집 ]

이 절의 가필 이 바람직합니다. |

Mindfulness 명상은 불면증과 싸울 수 있고 수면을 향상시킬 수 있습니다 [118] .

Mindfulness 무브먼트 [ 편집 ]

이 절의 가필 이 바람직합니다. |

서양 국가의 주류 연구에 따르면, 마음 풍뎅이는 지중해식이나 정기적인 운동만큼 뇌와 신체의 건강에 중요하다 [119] .

비평과 우려 [ 편집 ]

Mindfulness는 대유행하고 세속적인 목표 달성의 툴로 간주되고 있다. 간편한 '맥 마인드플루네스'라고 야기될 수도 있다 [120] .

세속적인 마인드플루네스는 불교적 마인드플루네스에 있던 진리와의 관계를 분리하고, 자의적인 아주 작은 테두리, 드루즈가 말하는 '컨트롤 사회'의 테두리에 맞추어 조정되고 있으며, 최근 미국에서는 군사훈련에서 사용되게 되어 있다 [16] . 이러한 편리하게 잘린 마인드플루네스의 '거세'가 초래하는 문제를 지적하는 목소리도 있다 [16] .

현대 마인드플루네스는 정견을 포함한 팔정도와 분리되어 '있는 그대로의 주의'라는 특별한 주의 기술, 또는 그것을 향상시키는 훈련 방법으로 실천되고 있으며, 불교의 접근과는 다르다 . 24] . 불교사이드로부터 다음과 같은 의견·우려도 전해지고 있다. 조동종 국제센터 소장 후지타 이치조는 현대적인 마인드풀네스처럼 불교에서 근본적인 오해( 무명 )라고 여겨지는 “자신이라는 것이 여기에 있고 그것과 분리된 형태로 여러 가지 나 사람이 자신 주위에 존재한다"는 분리·분단의 비전에 근거해 마인드플루네스를 실시하면, 그 비전이 강화되어 "호흡에 대한 주의"와 함께 "호흡에 대해 마인드풀이든 노력하고 있는 나라는 의식」도 강화된다. 호흡과의 단절은 깊어지고 힘을 주는 마인드플루니스가 될 수밖에 없다고 의견하고 있다 [121] . 불교적으로 말하면, 마인드플루니스는 '그냥 마인드플루네스'가 아니라 정견에 상응한 정념, 올바른 마인드플루니스여야 하며, '나'에게 있어서의 메리트, 측정 가능한 효과를 찾아 마인드플루네스를 하는 것은 부처의 접근과는 정반대라고도 할 수 있고, 고통의 원인인 '내 의식'이 강화되어 해결과는 멀다고 한다 [24] . 정신과 의사의 북서 헌지도 마인드 플루네스와 무아은 깊은 관계가 있다고 지적하고, 마인드플루니스가 중시하는 명상에 대한 “내면에 너무 많은 주의를 기울이고 있다. 있다 [122] .

각주 [ 편집 ]

주석 [ 편집 ]

- ^ 또한 건포도 한 개 먹기: 유인물 파일에 대한 마음챙김의 첫 맛을 참조하십시오.

- ^ mindfulness라는 영어 단어는 ' 마음 , 잊지 말고, 조심하다, 주의깊다'라는 의미의 형용사 인 영어 : mindful [51] 의 명사형 [52] 이며, 영어의 의미는 '주의 하고 있는 것, 잊지 않는 것 [52]」.

- ^ " 동사 의 파도 : sarati 에서 유래하고 "to remember"(추억, 기억하고 있는 [54] 를 의미한다)를 의미하는 sati는, 기억 이라는 관념과 연관시켜 설명되는 것이 지금도 때때로 있다. 그러나 sati가 명상 실천과 관련하여 사용될 때, 그 sati가 가리키는 의미를 정확하게 나타내는 영어 단어는 없다. 어쨌든,이 단어는 훌륭하게 역할을하고 있지만 "기억"과의 관계를 유지하지 않았으며 의미를 이루기 위해 문장 절을 필요로하는 경우도있었습니다 . 69] ”.

- ↑ Vipassana movement 의 지도자에 의해 교수된 비파사나 명상 은 서양의 모더니즘 에 영향을 받고 거기에 반발하여 19세기 에 개발된 것이다 [91] [92] . Buddhist modernism 도 참조.

- ↑ Frauwallner, E. (1973), 인도 철학의 역사 , 트랜스. VM Bedekar, 델리: Motilal Banarsidass. 두 권, pp.150 ff

- ^ “역사적으로 불교 의 수행인 마인드플루네스는 명백한 사고와 열린 마음을 육성하는 보편적인 능력으로 볼 수 있다. 이 명상 방식 자체는 특정 종교적 신앙 문화적 신념 체계 가 필요하지 않습니다.” - Mindfulness in Medicine by Ludwig and Kabat-Zinn, available at jama.ama-assn.org

출처 [ 편집 ]

- ^ a b c d 임상 개입으로서의 마음챙김 훈련: Ruth A. Baer의 개념적 및 경험적 검토, http://www.wisebrain.org/papers/MindfulnessPsyTx.pdf 에서 확인 가능

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kabat-Zinn, J(2013). 완전한 재앙 생활: 몸과 마음의 지혜를 사용하여 스트레스, 고통 및 질병에 대처하기 . 뉴욕: Bantam Dell. ISBN 978-0-345-53972-4

- ^ a b c d Creswell JD(2017). "마음챙김 개입". 심리학의 연례 검토 68 . doi : 10.1146/annurev-psych-042716-051139 .

- ↑ 루츠, 앙투안; 데이비슨, 리처드 J; 슬래그, 헬린 A(2011). "뇌와 인지 가소성에 대한 신경과학적 연구의 도구로서의 정신 훈련". 인간 신경 과학 5 . 도이 : 10.3389/fnhum.2011.00017 .

- ↑ 프란체스코의 파그니니; 필립스, 데보라(2015). “마음챙김에 대한 마음챙김”. The Lancet Psychiatry 2 (4): 288-289. 도이 : 10.1016/s2215-0366(15)00041-3 . PMID 26360065 .

- ↑ 「일상으로 명상 자신 객관시」 「요미우리 신문」2018년 3월 20일자 조간, 생활 가정면.

- ^ a b c d e f g h 키타가와 · 무토 2013 .

- ^ a b c d Fujii 2017 , p. 63.

- ↑ a b 후지노 2017 , pp. 212–213.

- ↑ “ Meditation & Mindfulness - Meditation and the Brain ” (일본어). Coursera . 2020년 9월 9일에 확인함.

- ↑ “ Sati ”. The Pali Text Society's Pali-English Dictionary . Digital Dictionaries of South Asia, University of Chicago. 2016년 10월 11일에 확인함. [ 링크 부족 ]

- ^ a b 후지타 2016 , pp. 69–70.

- ^ a b c d e f 지가하라 2018 .

- ^ a b c d e Karunamuni, Nandini; Weerasekera, Rasanjala(2017). “마음챙김 명상을 인도하는 이론적 기초: 지혜의 길”. 현재 심리학 . 도이 : 10.1007/s12144-017-9631-7 .

- ↑ 밴 고든, 윌리엄; 쇼닌, 에도; 그리피스, 마크 D; Singh, Nirbhay N(2014). “단 하나의 마음챙김: 과학과 불교가 함께 협력해야 하는 이유”. 마음챙김 6 : 49-56. 도이 : 10.1007/s12671-014-0379-y .

- ^ a b c d e 나가사와 2017 , pp. 62.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Sugamura 2016 , p. 133.

- ^ a b c d Fujii 2017 , p. 64.

- ^ Dukkha 자석 영역에서: Barbara Grahm의 Jon Kabat-Zinn과의 인터뷰. 세발자전거. http://tricycle.org/magazine/dukkha-magnet-zone/

- ^ b 해링턴 , 앤; 던, 존 D(2015). “마음챙김이 치료일 때: 윤리적 불안, 역사적 관점”. 미국 심리학자 70 (7): 621-631. 도이 : 10.1037/a0039460 . PMID 26436312 .

- ^ a b 베이 밸리 2016 , 1페이지.

- ↑ 후지타 2016 , 66쪽.

- ↑ 후지타 2016 , pp. 68–72.

- ↑ a b c 후지타 2016 , pp. 69–72.

- ↑ a b c 사이토 2017 , pp. 117–118.

- ^ b 케르 스트 렛, 새벽; 크로플리, 마크 (2013). “반추 및/또는 걱정을 줄이는 데 사용되는 치료법 평가: 체계적인 검토”. 임상 심리학 리뷰 33 (8): 996-1009. 도이 : 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.08.004 . PMID 24036088 .

- ^ 구, 제니; 슈트라우스, 클라라; 본드, 로드; 카바나, 케이트(2015). “마음챙김 기반 인지 치료와 마음챙김 기반 스트레스 감소는 어떻게 정신 건강과 웰빙을 향상시키는가? 중재 연구의 체계적인 검토 및 메타 분석”. 임상 심리학 리뷰 37 : 1-12. 도이 : 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.01.006 . PMID 25689576 .

- ^ b 슈트라우스 , 클라라; 카바나, 케이트; 올리버, 애니; Pettman, Danelle (2014). “현재 불안 또는 우울 장애 에피소드로 진단받은 사람들을 위한 마음챙김 기반 중재: 무작위 대조 시험의 메타 분석” . 플로스 원 9 (4): e96110. Bibcode : 2014PLoSO...996110S . 도이 : 10.1371/journal.pone.0096110 . PMC 3999148 . PMID 24763812 .

- ^ b c Khoury, Bassam ; 샤르마, 마노즈; 러쉬, 사라 E; 푸르니에, 클로드(2015). "건강한 개인을 위한 마음챙김 기반 스트레스 감소: 메타 분석". Journal of Psychosomatic Research 78 (6): 519-528. doi : 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.03.009 . PMID 25818837 .

- ↑ 자인, 펠리페 A; 월시, 로저 N; 아이젠드라스, 스튜어트 J; 크리스텐슨, 스콧; 라엘 칸, B (2015). "우울 장애의 급성 및 아급성 단계 치료에 대한 명상 요법의 효능에 대한 비판적 분석: 체계적인 검토" . 심리학 56 (2): 140-152. 도이 : 10.1016/j.psym.2014.10.007 . PMC 4383597 . PMID 25591492 .

- ↑ 샤르마, 마노즈; 러시, 사라 E (2014). "건강한 개인을 위한 스트레스 관리 중재로서의 마음챙김 기반 스트레스 감소". 근거 기반 보완 및 대체 의학 저널 19 (4): 271-286. 도이 : 10.1177/2156587214543143 . PMID 25053754 .

- ^ b 호프만 , 스테판 G; 소여, 앨리스 T; Witt, Ashley A; 오, 다이애나(2010). “마음챙김 기반 치료가 불안과 우울증에 미치는 영향: 메타분석적 고찰” . 컨설팅 및 임상 심리학 저널 78 (2): 169-183. 도이 : 10.1037/a0018555 . PMC 2848393 . PMID 20350028 .

- ↑ 키에사, 알베르토; 세레티, 알레산드로(2013). “마음챙김 기반 중재가 약물 사용 장애에 효과적인가? 증거의 체계적인 검토”. 물질 사용 및 오용 49 (5): 492-512. 도이 : 10.3109/10826084.2013.770027 . PMID 23461667 .

- ^ 갈랜드, 에릭 L; 프뢰리거, 브렛; 하워드, 매튜 O (2014). "주의-평가-감정 인터페이스에서 중독의 신경인지 메커니즘을 목표로 하는 마음챙김 훈련" . 정신의학 4 : 173. doi : 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00173 . PMC 3887509 . PMID 24454293 .

- ↑ 블랙, 데이비드 S (2014). "마음챙김 기반 개입: 약물 사용, 오용 및 중독의 맥락에서 고통에 대한 해독제". 물질 사용 및 오용 49 (5): 487-491. 도이 : 10.3109/10826084.2014.860749 . PMID 24611846 .

- ↑ 오스트, J; 브래드쇼, T(2017). “정신병에 대한 마음챙김 개입: 문헌의 체계적인 검토”. 정신과 및 정신 건강 간호 저널 24 (1): 69-83. 도이 : 10.1111/jpm.12357 . PMID 27928859 .

- ↑ 크래머, 홀거; 로슈, 로미; 할러, 하이데마리; 랭호르스트, 조스트; 도보스, 구스타프(2017). “정신병에 대한 마음챙김 및 수용 기반 중재: 체계적인 검토 및 메타 분석” . 건강 및 의학의 글로벌 발전 5 (1): 30-43. 도이 : 10.7453/gahmj.2015.083 . PMC 4756771 . PMID 26937312 .

- ^ Tang, Yi-Yuan; Leve, Leslie D(2015). “예방 전략으로서의 마음챙김 명상에 대한 중개적 신경과학 관점” . 번역 행동 의학 6 (1): 63-72. 도이 : 10.1007/s13142-015-0360-x . PMC 4807201 . PMID 27012254 .

- ↑ 고팅크, 린스케 A; 추, 폴라; Busschbach, Jan J. V; 벤슨, 허버트; Fricchione, 그레고리 L; Hunink, MG 미리암(2015). "의료의 표준화된 마음챙김 기반 중재: RCT의 체계적인 검토 및 메타 분석 개요" . 플로스 원 10 (4): e0124344. Bibcode : 2015PLoSO..1024344G . 도이 : 10.1371/journal.pone.0124344 . PMC 4400080 . PMID 25881019 .

- ↑ Paulus, Martin P (2016). "뇌에 대한 스트레스의 영향을 조절하는 마음챙김 중재의 신경 기반" . Neuropsychopharmacology 41 (1): 373. doi : 10.1038/npp.2015.239 . PMC 4677133 . PMID 26657952 .

- ^ Keng, Shian-Ling; 스모스키, 모리아 J; 로빈스, 클라이브 J (2011). “마음챙김이 심리적 건강에 미치는 영향: 경험적 연구 검토” . 임상 심리학 리뷰 31 (6): 1041-1056. 도이 : 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.04.006 . PMC 3679190 . PMID 21802619 .

- ^ a b Gunaratana, Bhante (2011). Mindfulness in plain English . Boston: Wisdom Publications. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-86171-906-8 2015년 1월 30일에 확인함.

- ^ a b c d Fujita 2016 , p. 67.

- ↑ Komaroff, Anthony (2014년 3월 31일). “ Does "mindfulness meditation" really help relieve stress and anxiety? ”. Ask Doctor K . Harvard Health Publications. 2014년 4월 22일에 확인함.

- ↑ 윌슨 2014 .

- ↑ 그들과 플린 2008 , p. 148

- ^ Teasdale & Segal 2007년 , p. 55-56.

- ^ b Pickert , K(2014). “마음챙김의 기술. 스트레스를 받고 디지털에 의존하는 문화에서 평화를 찾는 것은 다르게 생각하는 문제일 수 있습니다.” 시간 183 (4): 40-46. PMID 24640415 .

- ↑ 카루나무니, N.D(2015). "마음의 오집합 모델". 세이지 오픈 5 (2). 도이 : 10.1177/2158244015583860 .

- ↑ 브라운, 커크 워렌; 라이언, 리처드 M; Creswell, J. David (2007). “마음챙김: 유익한 효과에 대한 이론적 토대와 증거”. 심리상담 18 (4): 211-237. 도이 : 10.1080/10478400701598298 .

- ↑ 새로운 크라운 영어 사전 1996 , p. 838.

- ^ a b c “ mindfulness란 무엇입니까 - 생명 과학 사전 Weblio 사전 ”. Weblio. 2018년 2월 17일에 확인함.

- ^ a b 샤프 2014 , p. 942.

- ^ a b 새로운 크라운 영어 사전 1996 , p. 1116.

- ^ a b 새로운 크라운 영어 사전 1996 , p. 1099.

- ^ “ bear in mind란-영화 사전 Weblio 사전 ”. Weblio. 2018년 2월 17일에 확인함.

- ↑ 샤프 2014 , p. 942-943.

- ↑ 스가무라 2016 , pp. 130–131.

- ↑ 후지타 2016 , 131쪽.

- ↑ 후지타 2016 , pp. 131–132.

- ^ a b c 스가무라 2016 , p. 132.

- ↑ 새로운 크라운 영어 사전 1996 , p. 264.

- ↑ 새로운 크라운 영어 사전 1996 , p. 824.

- ↑ Gogerly, DJ (1845). “불교에 대하여”. 왕립아시아학회 실론지회지 1 : 7-28.

- ↑ 데이비드 1881 , p. 107.

- ↑ 데이비드 1881 , p. 145.

- ^ 스탠포드 대학 연민 및 이타주의 연구 및 교육 센터 강의(Wayback Machine、2012年11月20日) - http://ccare.stanford.edu/node/21

- ↑ 새로운 크라운 영어 사전 1996 , p. 826.

- ^ a b “ Translator for the Buddha: An Interview with Bhikkhu Bodhi ”. www.inquiringmind.com . 2018년 1월 7일에 확인함.

- ^ a b 새로운 크라운 영어 사전 1996 , p. 74.

- ↑ 새로운 크라운 영어 사전 1996 , p. 80-81.

- ↑ 새로운 크라운 영어 사전 1996 , p. 676.

- ↑ James H. Austin(2014), Zen-Brain Horizons: 살아있는 선을 향하여 , MIT Press, p.83

- ↑ 새로운 크라운 영어 사전 1996 , p. 1134.

- ↑ 옥스포드 영어사전 , 2판, 2002

- ↑ “ state이란?-영화 사전 Weblio 사전 ”. Weblio. 2018년 2월 21일에 확인함.

- ↑ “ being이란-영화 사전 Weblio 사전 ”. Weblio. 2018년 2월 21일에 확인함.

- ↑ “ aware란-영화 사전 Weblio 사전 ”. Weblio. 2018년 2월 21일에 확인함.

- ^ a b c d “ MINDFULNESS에 대한 유의어 사전 결과 ”. www.merriam-webster.com 2018년 1월 7일 에 액세스 함 .

- ^ Kabat-Zin 2011년 , p. 22-23.

- ^ Kabat-Zin 2013 , p. 65.

- ↑ 새로운 크라운 영어 사전 1996 , p. 1525.

- ↑ “ Component Selection for 'mindfulness' ”. dico.isc.cnrs.fr. 2018 년 1월 7일에 확인함.

- ^ a b c “ I found great synonyms for "mindfulness" on the new Thesaurus.com! ”. www.thesaurus.com . 2018년 1월 7일에 확인함.

- ↑ 새로운 크라운 영화 사전 1996 , p. 31.

- ↑ 새로운 크라운 영화 사전 1996 , p. 1059.

- ↑ 새로운 크라운 영어 사전 1996 , p. 247.

- ↑ 새로운 크라운 영어 사전 1996 , p. 81.

- ↑ 새로운 크라운 영어 사전 1996 , p. 248.

- ↑ 새로운 크라운 영어 사전 1996 , p. 913.

- ↑ 맥마한 2008 .

- ↑ 샤프 & 1995-B .

- ^ “ The 18th Mind and Life Dialogues meeting ”. 2014년 3월 22일 시점의 오리지널 보다 아카이브. 2018년 1월 7일에 확인함.

- ↑ Sister Ayya Khema. “ All of Us ”. Access to Insight. 2009년 3월 16일에 확인함.

- ↑ Bhikkhu Bodhi. “ The Noble Eightfold Path ”. Access to Insight. 2009년 3월 16일에 확인함.

- ↑ 비쿠의 아날라요(2003). Satipaṭṭhāna, 깨달음에 이르는 직접적인 길 . 윈드호스 간행물

- ↑ 윌리엄스 2000 , p. 46.

- ↑ 베터 1988 .

- ↑ 리스 데이비스, TW (1959). 붓다의 대화, 2부 . 영국 옥스포드: 팔리어 텍스트 협회. 322-346쪽. ISBN 0 86013 034 7

- ↑ 후지타 2016 , 71쪽.

- ↑ "1979년 Dr. Jon Kabat-Zinn이 설립한 스트레스 감소 프로그램..." - http://www.umassmed.edu/cfm/stress/index.aspx

- ^ "마음챙김의 임상적 적용에 대한 많은 관심은 원래 만성 통증 관리를 위해 개발된 수동 치료 프로그램인 마음챙김 기반 스트레스 감소(Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction, MBSR)의 도입으로 촉발되었습니다(Kabat-Zinn, 1982; Kabat-Zinn , Lipworth, & Burney, 1985; Kabat-Zinn, Lipworth, Burney, & Sellers, 1987)" - Bishop et al, 2004, "마음챙김: 제안된 운영 정의"

- ^ Israel, Ira (2013년 5월 30일). “ What's the Difference Between Mindfulness, Mindfulness Meditation and Basic Meditation? ”. The Huffington Post . 2018년 2월 16일에 확인함.

- ↑ Bernhard, Toni (2011년 6월 6일). “ 6 Benefits of Practicing Mindfulness Outside of Meditation ”. Psychology Today . 2018년 2월 16일에 확인함.

- ↑ 아담 발레리오(2016). “마음챙김 소유: 불교 맥락 안팎에서 마음챙김 문학 경향에 대한 서지적 분석”. 현대불교 17 : 157-183. 도이 : 10.1080/14639947.2016.1162425 .

- ↑ 카바트진 2000 .

- ^ 임상 개입으로서의 마음챙김 훈련: Ruth A. Baer의 개념 및 경험적 검토

- ↑ 오렌 에르가스(2013). “과학, 종교, 치유의 교차점에서 교육의 마음챙김”. 교육의 비판적 연구 55 : 58-72. 도이 : 10.1080/17508487.2014.858643 .

- ^ a b c 히사모토 2008 .

- ^ a b c d e f 나카노 2005 , pp. 173–176.

- ↑ 정신과 치료학 32권 07호 초록 본문 성화서점

- ^ a b c d 소노다 2010 .

- ^ a b c 소노다 등 2017 .

- ↑ 게이오 대학 정신·신경과 모리타 요법 게이오 대학 2017년 1월 24일

- ↑ North Westb 2016 , 130쪽.

- ↑ a b 북서b 2016 , pp. 210–212.

- ↑ 북서 b 2016 , pp. 130–131.

- ^ Corliss, Julie (2015년 2월 18일). “ Mindfulness meditation helps fight insomnia, improves sleep ” (영어). Harvard Health . 2022년 1월 13일에 확인함.

- ^ " 뇌의 건강을 바이오해킹 "(일본어). Coursera . 2022년 1월 13일 에 액세스함 .

- ↑ 샬럿 리버맨 마인드플루네스는 목표 달성에 도움이 되는 도구가 아니다 Harvard Business Review 2015.11.27

- ↑ 후지타 2016 , pp. 73-74.

- ↑ 북서 a 2016 .

참고 문헌 [ 편집 ]

- 이넨, 앤; 플린, 캐롤린(2008), 마음챙김에 대한 완전한 바보 가이드 , 펭귄

- Teasdale, 존 D.; Segal, Zindel V. (2007), 우울증을 통한 마음챙김 방법: 만성적 불행에서 벗어나기 , Guilford Press

- 윌슨, 제프(2014), Mindful America: Meditation and the Mutual Transformation of Buddha and American Culture , Oxford University Press

- McMahan, David L. (2008), 불교 모더니즘 만들기 , Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195183276

- Vetter, Tilmann(1988), 초기 불교의 사상과 명상 수행 , BRILL

- 샤프, 로버트 (1995). “불교 모더니즘과 명상적 경험의 수사학”. 민수 42 (3): 228-283 . 도이 : 10.1163/1568527952598549 . JSTOR 3270219 .

- 윌리엄스, 폴; Tribe, Anthony (2000), 불교 사상 , Routledge

- Kabat-Zinn, Jon (2000). “참여의학”. 유럽 피부과 및 성병 학회지 14 (4): 239-240. 도이 : 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2000.00062.x . PMID 11204505 .

- 리네한, 마샤(1993). 경계성 인격 장애의 인지 행동 치료 . 길포드 프레스.

- “초선의 마음챙김과 마음없음”. 철학 동양과 서양 64 (4): 933-964. (2014). 도이 : 10.1353/pew.2014.0074 .

- TW Rhys Davids (1881). 불교 경전 . 클라렌던 프레스. OCLC 13247398

- 카와무라 시게지로 편 『신크라운 영화사전』(제5판) 삼성당, 1996년 2월.

- 나카노 케이코 『스트레스 매니지먼트 입문 자기 진단과 대처를 배우는 제2판』 김강 출판, 2005년.

- 쿠모토 히로유키 「행동, 사고로부터 주의에: 행동 요법의 변천과 마인드플루네스(Mindfulness)(특집 감정 심리학의 응용)」 「간사이대학 사회학부 기요」 제39권 제2호, 간사이대학 사회학부, 2008 년, 133-146페이지, ISSN 02876817 , NAID 110007153013 。

- 소노다 준이치 「ACT란 무엇인가」 「요시비 국제 대학 임상 심리 상담 연구소 기요」 제7권, 요시비 국제 대학, 2010년, 45-50.

- 키타가와 카노, 무토 타카시 「마인드 플루네스의 촉진 곤란에의 대응 방법이란 무엇인가」 「심리 임상 과학」 제3권 제1호, 심리 임상 과학 편집 위원회, 2013년 12월, 41-51페이지 , doi : 10.14988/pa.2017.0000013384 , ISSN 2186-4934 , NAID 120005641290 .

- 『마인드후루네스 기초와 실천』, 가미타니 히사요시 , 구마노 히로아키 , 고시 카와 보코편 저 일본 평론사, 2016년.

- 가이타니 히사요시 집필 「인트로덕션」.

- 후지타 카즈테리 집필 「불교에서 본 마인드플루네스 세속적 마인드플루네스에의 일제언」.

- 스가무라 겐지 집필 「마인드플루네스의 의미를 넘어서 말, 개념, 그리고 체험」.

- 키타니시 켄지 「마인드후루네스, 있는 그대로, 그리고 모리타 요법」 「심리 교육 상담실 연보」 제11권, 도쿄 대학 대학원 교육학 연구과 부속 심리 교육 상담실, 2016년, 5-13페이지.

- 키타니시 켄지 『처음의 모리타 요법』 코단샤, 2016년.

- 사이토 쇼이치로 「심리 요법으로서의 마인드플루니스에 있어서의 불교성 」 「와세다 대학 고등학원 연구 연지」 제61호, 와세다 대학 고등학원, 2017년 3월, 140-128페이지 , ISSN 0287-1653 , 023

- 후지이 슈헤이 「마인드 플루 네스의 유래와 전개 5688 , NAID 40021420726 .

- 소노다 쥰이치, 타케이 미치코, 다카야마 미야, 히라카와 타다토시, 마에다 나오키, 하타다 에이이치로, 쿠로하마 쇼타, 노소에 신이치 4호, 일본 심신의학회, 2017년, 329-334페이지, doi : 10.15064/jjpm.57.4_329 , ISSN 0385-0307 , NAID 130005530169 .

- 『신심변용의 과학 명상의 과학―마인드플루네스의 뇌과학부터 공명하는 신체지에 이르기까지 명상을 과학하는 시도―신심변용기법 시리즈 1』, 가마타 히가시니편 산가 , 2017년.

- 나가사와 테츠 집필 「명상의 뇌과학의 현재」.

- 후지노 마사히로 집필 「명상의 신경과학 연구 1인칭 체험에 근거한 3인칭 과학」.

- 지하라 마사시 「미치모토 선과 마인드 플루네스 (3) : 그 정리와 실천」NAID 120006821643 .

- "마인드 풀니스 스트레스 저감법"존 카바트 진 하루키 토요 (번역) 2007/09 키타 오지 서방

관련 항목 [ 편집 ]

외부 링크 [ 편집 ]

사티 (불교)

| 불교 용어 사티 | |

|---|---|

| 파리어 | sati (सति) |

| 산스크리트어 | smṛti (स्मृति) |

| 티베트어 | དྲན་པ། ( Wylie : dran pa; THL : trenpa/drenpa ) |

| 중국어 | nian, 만 |

| 일본어 | ( 로마자 : nen ) |

| 한국어 | 염 ( RR : yeom or yŏm ) |

| 영어 | mindfulness, awareness, inspection, recollection, retention |

| 신하라어 | සති |

| 베트남어 | niệm |

파리어로 사티 (巴: sati [1] ,梵: smṛti [1] : 스무리티)란 특정한 일을 마음에 (항상) 두는 것이다. 일본어로

위치 설정[ 편집 ]

념은, 오근 이라는 수행의 근본이 되는 5개의 능력의 하나이며, 마음에 유지하는 능력을 가리킨다 [3] . 상좌부 불교 의 텍스트에서는, 만일 이외는, 그 힘이 너무 강해도, 수행의 방해가 되기 때문에, 각각의 힘이 균형에 작용하는 것을 명상 수행을 통해서 목표로 한다 [3] . 념은 그러한 방해가 되지 않기 때문에, 강할수록 강할수록 좋다 [3] . 대승불교 에서도 신앙과 지혜 , 노력과 선정 등은 쌍이며, 그 힘의 발달에는 균형이 필요하다 [4] .

상좌부의 비파사나 명상 에 있어서, 마음의 상태나, 신체의 행위 등 대상을 「기념한다」라고 하는 때에는, 오근이라고 하는 5개의 능력을 일으키고 있는 것을 가리키고 있다 [3] .

또 대승불교의 선정의 실천에 있어서도 선정의 완성을 위해서는 부단한 주의 깊이에 의해 대상에 집중하는 상태를 확보함으로써 따라서 완전한 주의 깊이인 정념 (sammāsati)이 된다 . 4] . 실념이란, 이 주의 깊이가 결여된 상태이며, 정념에 대립한다 [4] . 「상응부」(산유타·니카야)에 있어서도, 생각은 모든 곳에서 도움이 되는 것이라고 설해진다 [4] . 와츠지 테츠로 는 『원시불교의 실천철학』에서 정념이란 「걸리는 정당한 전념 집주」라고 적고 있다 .

설명 [ 편집 ]

모든 것에 옮겨간다는 마음의 산만한 움직임을 자각할 수 있게 되는 것을 깨닫고 마음에 머무는 훈련은 가장 기초적이며, 자신의 호흡을 관찰하는 것이 가장 기초적이고 최적 라고 한다 [6] . 지속적인 훈련을 통해 더 작은 노력으로 수행 할 수 있으며 결국 자동으로 수행 할 수 있습니다 [6] .

그 특정한 것에 집착하거나 혐오의 대상으로 되돌리도록 대치하는 것이 아니라, 중립적인 상태에서 가치 판단을 가하지 않고, 의식을 대상물에 멈추어 두는 것이다. 또, 항상 의식을 대상물에 멈추는 것으로, 의식의 대상물에 대한 주의가 끊긴다고 하는 것, 다른 것에 신경쓰이는 다른 것에 의식이 가는 일도 없고, 경과하는 시간을 잊는다고 하는 일도 없다 라고 한다.

마음이 깊어지면 의식이 완전히 고정되어 움직이지 않게 되는 정 (조, 서머디)에 이르고,

멈춤 (사마타)의 의식 대상은 40정도에 즈음해, 숨 등의 생리 현상 등으로부터, 불 · 법 · 승려 나 계명 , 신들 , 또 희폐하 는 것을 마음에 들고 거기에 집중하는 것도 염이라고 한다. 예를 들어, 부처님을 마음에 상기시켜 이것에 집중하는 것은 불수념 혹은 염불(buddhānusmṛti)이라고 한다. 이 6가지 생각하는 대상을 특히 육념처 라고 부른다.

티베트 불교 에서는 중지를 먼저 실천하고 최고위의 상태에 이르고 나서 관 수행에 들어간다. 관을 실천할 뿐이라면, 도중 단계의 정지 능력으로 실천할 수 있다.

반대로, 최근에 특히 구미에서 널리 퍼진 비파사나 (관)에서는, 이념의 대상을 40정도의 사마타의 전통적인 대상물이 아니고, 처음부터 사물의 변화를 향하기 위해, 염을 깊게 정해 이르더라도 삼매의 경지에 들어갈 수 없다. 또, 만약의 대상을 항상 변화하는 현상을 향하기 위해, 변화에 연속적으로 「깨닫는다」라고 하는 의미가 되지만, 사마타의 경우는 대상물이 고정되어 있기 때문에 「신경쓰기」혹은 「의식을 고정 한다'는 의미로 '심심'이 적절한 번역이 된다. 만약의 도중에 '깨달음' 때마다 삼매에서 빠져 버린다는 의미에서는 뜻의 번역으로 '깨닫는'은 적합하지 않다. 비파사나에서는 사티란, 「지금의 순간에 생기는, 모든 일에 주의를 돌려, 중립적으로 잘 관찰해, 지금·여기를 눈치채고 있다」라고 한다. 이런 관행에 이르는 경지와 지행으로 이어지는 경지의 차이가 나타난다.

선의 염 [ 편집 ]

념은 기본적으로 명상중으로 하는 것으로, 좌선 , 경행 , 입선중에 실시한다. 또 청소나 접시세척이나 재봉 등 일상생활의 간단한 동작 자체를 염려의 대상으로 하기도 한다. 앞으로 궁극적으로는 일중이나 대화중 등 일상 생활에서 복잡한 작업을 하고 있을 때에도 항상 염려할 수 있게 된다고 한다 [ 누구에 의해? ] .

의료 [ 편집 ]

영어의 Mindfullness (Mindfullness)는 1900년에 영국의 리스 데이비스가 파리어의 사티를 영역하고 나서 사용되게 되었다 [7] . 불교도도 영어로는 마인드플루니스라는 말을 쓴다 [4] .

생활 방식으로서의 마인드플루니스에는 2500년의 전통이 있지만, 이 마인드플루네스를 구미에서는 최근 들어 건강관리에 응용하고 있다 . 서양의 심리학에서의 마인드플루니스는 불교에서의 것을 반영하고 있지만, 차이도 보인다 [9] . 서양의 심리학에서는 신체나 심리적 측면을 연구하기 위해 서양의 세속적인 맥락에서 해석하고 있지만, 불교에서는 고통의 성질과 거기로부터의 정신적인 자유를 목적으로 한 실천이다 . 10] .

1979년에는 존 카바트 진이 통증 환자 의 치료에 만드플루네스의 실천을 통합하여 마인드플루네스 스트레스 저감법 ( MBSR )이라고 불리게 된다 . 카바트 진은 1970년대 초반에는 매사추세츠공과대학 (MIT)에서 분자생물학 의 박사 학위 를 취득하고 선 의사에 의한 명상에 대한 강의에 참가해 그 날에 명상을 시작했다 [11] . 카바트 진이 2012년 일본을 방문했을 때, 기본 이념은 도모젠 선사의 조동종 이라고 말하고 있다 [12] .

MBSR은 카바트 진 하에서 배운 윌리엄스와 갈매기, 티즈데일에 의해 마인드플루네스 인지요법 (MBCT)으로 발전하여 우울증 치료에 응용되어 다른 건강 문제에 대해서도 신속하게 퍼졌다 [8] . 상기 두 가지 요법은 마인드플루니스의 훈련에 기초한 것이고, 마인드플루니스의 훈련을 포함한 것에는 변증법적 행동요법 이 있다 [7] .

サティ (仏教)

| 仏教用語 サティ | |

|---|---|

| パーリ語 | sati (सति) |

| サンスクリット語 | smṛti (स्मृति) |

| チベット語 | དྲན་པ། (Wylie: dran pa; THL: trenpa/drenpa) |

| 中国語 | nian, 念 |

| 日本語 | (ローマ字: nen) |

| 韓国語 | 염 (RR: yeom or yŏm) |

| 英語 | mindfulness、awareness、inspection、recollection、retention |

| シンハラ語 | සති |

| ベトナム語 | niệm |

パーリ語でサティ(巴: sati[1]、梵: smṛti[1]:スムリティ)とは、特定の物事を心に(常に)留めておくことである。日本語では

位置づけ[編集]

念は、五根という修行の根本となる5つの能力のひとつであり、心に維持する能力を指す[3]。上座部仏教のテキストでは、念以外は、その力が強すぎても、修行の妨げとなるため、それぞれの力が均衡にはたらくことを瞑想修行を通して目指していく[3]。念はそういった妨げとならないので、強ければ強いほどいい[3]。大乗仏教においても、信仰と智慧、努力と禅定などは対であり、その力の発達には均衡が必要である[4]。

上座部のヴィパッサナー瞑想において、心の状態や、身体の行為など対象を「念じる」という時には、五根という5つの能力をはたらかせているものを指している[3]。

また大乗仏教の禅定の実践においても、禅定の完成のためには、不断の注意深さによって対象に集中する状態を確保することで、ゆえに完全な注意深さである正念(sammāsati)となる[4]。失念とは、この注意深さに欠けた状態であり、正念に対立する[4]。『相応部』(サンユッタ・ニカーヤ)においても、念はあらゆるところで役立つものだと説かれる[4]。和辻哲郎は、『原始仏教の実践哲学』にて、正念とは「かかる正しき専念集注」だと記している[5]。

説明[編集]

あらゆるものへ移っていくという心の散漫な動きを自覚することができるようになる、気づき、心にとどめるという訓練は最も基礎的であり、自分の呼吸を観察するのが一番基礎的で最適だとされる[6]。持続的な訓練によって、より小さな努力で行えるようになり、最終的には自動的に行うことができる[6]。

その特定のことに執着したり、嫌悪の対象として押し戻すように対峙するのではなく、中立的な状態で価値判断を加えることなく、意識を対象物に止めておくことである。また、常に意識を対象物に止めることで、意識の対象物に対する注意が途切れるということや、他の事に気が迷い別のことに意識が向かうこともなく、経つ時間を忘れるということもないとされる。

念が深まると意識が完全に固定され動かなくなる定(じょう、サマーディ)に至り、

止(サマタ)の意識の対象は40程にあたり、息などの生理現象などから、仏・法・僧や戒、神々、また喜捨することを心に浮かべてそれに集中することも念という。例えば、仏を心に想起してこれに集中することは仏随念あるいは念仏 (buddhānusmṛti) という。これらの6つの念じる対象を特に六念処と呼ぶ。

チベット仏教では、止を先に実践し最高位の状態へと至ってから、観の修行に入る。観を実践するだけであれば、途中の段階の止の能力にて実践することができる。

対して、近年で特に欧米で広く広まったヴィパッサナー(観)では、この念の対象を40程のサマタの伝統的な対象物でなく、最初から物事の変化に向けるため、念を深めて定に至っても三昧の境地に入ることはできない。また、念の対象を常に変化する現象に向けるため、変化に連続的に「気づく」という意味となるが、サマタの場合は対象物が固定されているので「気に留める」あるいは「意識を固定する」という意味で「念ずる」が適切な訳となる。念の途中で「気づく」たびに三昧から抜けてしまうという意味では念の訳として「気づく」は適さない。ヴィパッサナーではサティとは、「今の瞬間に生じる、あらゆる事柄に注意を向けて、中立的によく観察し、今・ここに気づいている」ことであるとされる。この様な観行にいたる境地と止行により至る境地の違いが現れる。

禅における念[編集]

念は基本的に瞑想中にするもので、坐禅、経行、立禅の最中に行う。また掃除や皿洗いや裁縫などの日常生活の簡単な動作そのものを念の対象とすることもある。これから最終的には仕事中や会話中などの日々の生活において複雑な作業をしているときでも常に念を行えるようになるとされる[誰によって?]。

医療[編集]

英語のマインドフルネス (Mindfullness) は、1900年にイギリスのリース・デービッスがパーリ語のサティを英訳してから使われるようになった[7]。仏教徒も英語ではマインドフルネスという言葉を使う[4]。

生き方としてのマインドフルネスには2500年の伝統があるが、このマインドフルネスを欧米では近年に入り健康管理に応用している[8]。西洋の心理学におけるマインドフルネスは、仏教におけるものを反映しているが、相違も見られる[9]。西洋の心理学では身体や心理的側面を研究するために、西洋の世俗的な文脈で解釈しているが、仏教では苦しみの性質とそこからの精神的な自由を目的とした実践である[10]。

1979年にはジョン・カバット・ジンが、疼痛患者の治療にマンドフルネスの実践を統合しマインドフルネスストレス低減法 (MBSR) と呼ばれることになる[8]。カバット・ジンは、1970年代初頭にはマサチューセッツ工科大学(MIT)にて分子生物学の博士号を取得し、禅の師による瞑想についての講義に参加しその日に瞑想をはじめた[11]。カバット・ジンが2012年に日本に訪れた際、基本理念は道元禅師の曹洞宗だと述べている[12]。

MBSRは、カバット・ジンの下で学んだウィリアムズとシーガル、ティーズデールによってマインドフルネス認知療法 (MBCT) へと発展し、うつ病の治療のために応用され、他の健康の問題に対しても迅速に広まっていった[8]。以上2つの療法はマインドフルネスの訓練に基づいたものであり、マインドフルネスの訓練を組み込んだものには弁証法的行動療法がある[7]。

脚注[編集]

注釈[編集]

出典[編集]

- ^ a b c 「念」 『オックスフォード仏教辞典』朝倉書店、2016年、263頁。ISBN 978-4-254-50019-6。

- ^ a b 藤永保監修 『最新心理学事典』平凡社、2013年、894頁。ISBN 9784582106039。

- ^ a b c d マハーシ長老 著、ウ・ウィジャナンダー 訳 『ミャンマーの瞑想―ウィパッサナー観法』国際語学社、1996年、80-81、158、164-165頁。ISBN 4-87731-024-X。

- ^ a b c d e ダライ・ラマ14世テンジン・ギャツォ 著、菅沼晃 訳 『ダライ・ラマ 智慧の眼をひらく』春秋社、2001年、106-108、176-177頁。ISBN 978-4-393-13335-4。 全面的な再改訳版。(初版『大乗仏教入門』1980年、改訳『智慧の眼』1988年)The Opening of the Wisdom-Eye: And the History of the Advancement of Buddhadharma in Tibet, 1966, rep, 1977。上座部仏教における注釈も備える。

- ^ 和辻哲郎 『原始仏教の実践哲学』(改定版)岩波書店、1932年、416頁。 初版1926年。

- ^ a b ダライ・ラマ 著、伊藤真 訳 『科学への旅 原子の中の宇宙』サンガ、2007年、197-208頁。ISBN 978-4901679428。

- ^ a b 菅村玄二、(本文著者)Z・V・シーガル、J・M・G・ウィリアムズ、J・D・ティーズデール共著 著、越川房子 訳「補遺 マインドフルネス心理療法と仏教心理学」 『マインドフルネス認知療法 うつを予防する新しいアプローチ』北大路書房、2007年、270-281頁。ISBN 978-4-7628-2574-3。

- ^ a b c Veves, Aristidis; Gotink, Rinske A.; Chu, Paula; Busschbach, Jan J. V.; Benson, Herbert; Fricchione, Gregory L.; Hunink, M. G. Myriam (2015). “Standardised Mindfulness-Based Interventions in Healthcare: An Overview of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of RCTs”. PLOS ONE 10 (4): e0124344. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0124344. PMC 4400080. PMID 25881019.

- ^ Grossman, Paul; Van Dam, Nicholas T. (2011). “Mindfulness, by any other name…: trials and tribulations ofsatiin western psychology and science” (pdf). Contemporary Buddhism 12 (1): 219–239. doi:10.1080/14639947.2011.564841.

- ^ Epel E, Daubenmier J, Moskowitz JT, Folkman S, Blackburn E (2009). “Can meditation slow rate of cellular aging? Cognitive stress, mindfulness, and telomeres”. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1172: 34–53. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04414.x. PMC 3057175. PMID 19735238.

- ^ Kate Pickert (2014年1月23日). “The Mindful Revolution”. Time 2015年9月20日閲覧。

- ^ (編著)貝谷久宣、熊野宏昭、越川房子 『マインドフルネス 基礎と実践』日本評論社、2016年、i頁。ISBN 978-4-535-98424-0。

関連項目[編集]

外部リンク[編集]

Sati (Buddhism)

This article or section should specify the language of its non-English content, using {{lang}}, {{transliteration}} for transliterated languages, and {{IPA}} for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriate ISO 639 code. Wikipedia's multilingual support templates may also be used. (December 2021) |

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Mindfulness |

|---|

|

| Category:Mindfulness |

Sati (Pali: सति;[1] Sanskrit: स्मृति smṛti) is mindfulness or awareness, a spiritual or psychological faculty (indriya) that forms an essential part of Buddhist practice. It is the first factor of the Seven Factors of Enlightenment. "Correct" or "right" mindfulness (Pali: sammā-sati, Sanskrit samyak-smṛti) is the seventh element of the Noble Eightfold Path.

Definition[edit]

The Buddhist term translated into English as "mindfulness" originates in the Pali term sati and in its Sanskrit counterpart smṛti. According to Robert Sharf, the meaning of these terms has been the topic of extensive debate and discussion.[2] Smṛti originally meant "to remember", "to recollect", "to bear in mind", as in the Vedic tradition of remembering sacred texts. The term sati also means "to remember" the teachings of scriptures. In the Satipațțhāna-sutta the term sati means to maintain awareness of reality, where sense-perceptions are understood to be illusions and thus the true nature of phenomena can be seen.[2] Sharf refers to the Milindapanha, which explained that the arising of sati calls to mind the wholesome dhammas such as the four establishments of mindfulness, the five faculties, the five powers, the seven awakening-factors, the Noble Eightfold Path, and the attainment of insight.[3] According to Rupert Gethin,

Sharf further notes that this has little to do with "bare attention", the popular contemporary interpretation of sati, "since it entails, among other things, the proper discrimination of the moral valence of phenomena as they arise".[4] According to Vetter, dhyana may have been the original core practice of the Buddha, which aided the maintenance of mindfulness.[5]

Etymology[edit]

| Translations of Mindfulness | |

|---|---|

| English | mindfulness, awareness, inspection, recollection, retention |

| Sanskrit | smṛti (स्मृति) |

| Pali | sati (सति) |

| Chinese | niàn, 念 |

| Japanese | 念 (ネン) (Rōmaji: nen) |

| Khmer | សតិ (UNGEGN: sate) |

| Korean | 념 (RR: nyeom) |

| Sinhala | සති |

| Tibetan | དྲན་པ (Wylie: dran pa; THL: trenpa/drenpa) |

| Thai | สติ (sati) |

| Vietnamese | niệm |

| Glossary of Buddhism | |

It originates from the Pali term sati and its Sanskrit counterpart smṛti. From Sanskrit it was translated into trenpa in Tibetan (transliteration: dran pa) and nian 念 in Chinese.

Pali[edit]

In 1881, Thomas William Rhys Davids first translated sati into English mindfulness in sammā-sati "Right Mindfulness; the active, watchful mind".[6] Noting that Daniel John Gogerly (1845) initially rendered sammā-sati as "Correct meditation",[7] Davids explained,

Henry Alabaster, in The Wheel of the Law: Buddhism Illustrated From Siamese Sources by the Modern Buddhist, A Life of Buddha, and an Account of the Phrabat (1871), had earlier defined "Satipatthan/Smrityupasthana" as "The act of keeping one's self mindful."[9]

The English term mindfulness already existed before it came to be used in a (western) Buddhist context. It was first recorded as mindfulness in 1530 (John Palsgrave translates French pensee), as mindfulnesse in 1561, and mindfulness in 1817. Morphologically earlier terms include mindful (first recorded in 1340), mindfully (1382), and the obsolete mindiness (ca. 1200).[10]

John D. Dunne, an associate professor at Emory University whose current research focuses especially on the concept of "mindfulness" in both theoretical and practical contexts, asserts that the translation of sati and smṛti as mindfulness is confusing and that a number of Buddhist scholars have started trying to establish "retention" as the preferred alternative.[11]

Bhikkhu Bodhi also points to the meaning of "sati" as "memory":

However, in What Does Mindfulness Really Mean? A Canonical Perspective (2011), Bhikkhu Bodhi pointed out that sati is not only "memory":

Also, he quoted the below-mentioned comment by Thomas William Rhys Davids as "remarkable acumen":

Sanskrit[edit]

The Sanskrit word smṛti स्मृति (also transliterated variously as smriti, smRti, or sm'Rti) literally means "that which is remembered", and refers both to "mindfulness" in Buddhism and "a category of metrical texts" in Hinduism, considered second in authority to the Śruti scriptures.

Monier Monier-Williams's Sanskrit-English Dictionary differentiates eight meanings of smṛti स्मृति, "remembrance, reminiscence, thinking of or upon, calling to mind, memory":

- memory as one of the Vyabhicāri-bhāvas [transient feelings];

- Memory (personified either as the daughter of Daksha and wife of Aṅgiras or as the daughter of Dharma and Medhā);

- the whole body of sacred tradition or what is remembered by human teachers (in contradistinction to Śruti or what is directly heard or revealed to the Rishis; in its widest acceptation this use of the term Smṛti includes the 6 Vedangas, the Sūtras both Śrauta and Grhya, the Manusmṛti, the Itihāsas (e.g., the Mahābhārata and Ramayana), the Puranas and the Nītiśāstras, "according to such and such a traditional precept or legal text";

- the whole body of codes of law as handed down memoriter or by tradition (esp. the codes of Manusmṛti, Yājñavalkya Smṛti and the 16 succeeding inspired lawgivers) … all these lawgivers being held to be inspired and to have based their precepts on the Vedas;

- symbolical name for the number 18 (from the 18 lawgivers above);

- a kind of meter;

- name of the letter g- ग्;

- desire, wish[14]

Chinese[edit]

Buddhist scholars translated smṛti with the Chinese word nian 念 "study; read aloud; think of; remember; remind". Nian is commonly used in Modern Standard Chinese words such as guannian 觀念 (观念) "concept; idea", huainian 懷念 (怀念) "cherish the memory of; think of", nianshu 念書 (念书) "read; study", and niantou 念頭 (念头) "thought; idea; intention". Two specialized Buddhist terms are nianfo 念佛 "chant the name of Buddha; pray to Buddha" and nianjing 念經 (念经) "chant/recite sutras".

This Chinese character nian 念 is composed of jin 今 "now; this" and xin 心 "heart; mind". Bernhard Karlgren graphically explains nian meaning "reflect, think; to study, learn by heart, remember; recite, read – to have 今 present to 心 the mind".[15] The Chinese character nian or nien 念 is pronounced as Korean yeom or yŏm 염, Japanese ネン or nen, and Vietnamese niệm.

A Dictionary of Chinese Buddhist Terms gives basic translations of nian: "Recollection, memory; to think on, reflect; repeat, intone; a thought; a moment."[16]

The Digital Dictionary of Buddhism gives more detailed translations of nian "mindfulness, memory":

- Recollection (Skt. smṛti; Tib. dran pa). To recall, remember. That which is remembered. The function of remembering. The operation of the mind of not forgetting an object. Awareness, concentration. Mindfulness of the Buddha, as in Pure Land practice. In Abhidharma-kośa theory, one of the ten omnipresent factors 大地法. In Yogâcāra, one of the five 'object-dependent' mental factors 五別境;

- Settled recollection; (Skt. sthāpana; Tib. gnas pa). To ascertain one's thoughts;

- To think within one's mind (without expressing in speech). To contemplate; meditative wisdom;

- Mind, consciousness;

- A thought; a thought-moment; an instant of thought. (Skt. kṣana);

- Patience, forbearance.[17]

Alternate translations[edit]

The terms sati/smriti have been translated as:

- Attention (Jack Kornfield)

- Awareness

- Concentrated attention (Mahasi Sayadaw)

- Inspection (Herbert Guenther)

- Mindful attention

- Mindfulness

- Recollecting mindfulness (Alexander Berzin)

- Recollection (Erik Pema Kunsang, Buddhadasa Bhikkhu)

- Reflective awareness (Buddhadasa Bhikkhu)

- Remindfulness (James H. Austin)[18]

- Retention

- Self-recollection (Jack Kornfield)

Practice[edit]

Originally, mindfulness provided the way to liberation, by paying attention to sensory experience, preventing the arising of disturbing thoughts and emotions which cause the further chain of reactions leading to rebirth.[19][20] In the later tradition, especially Theravada, mindfulness is an antidote to delusion (Pali: Moha), and is considered as such one of the 'powers' (Pali: bala) that contribute to the attainment of nirvana, in particular when it is coupled with clear comprehension of whatever is taking place. Nirvana is a state of being in which greed, hatred and delusion (Pali: moha) have been overcome and abandoned, and are absent from the mind.

Satipaṭṭhāna - guarding the senses[edit]

The Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta (Sanskrit: Smṛtyupasthāna Sūtra) is an early text dealing with mindfulness. The Theravada Nikayas prescribe that one should establish mindfulness (satipaṭṭhāna) in one's day-to-day life, maintaining as much as possible a calm awareness of the four upassanā: one's body, feelings, mind, and dharmas.

According to Grzegorz Polak, the four upassanā have been misunderstood by the developing Buddhist tradition, including Theravada, to refer to four different foundations. According to Polak, the four upassanā do not refer to four different foundations, but to the awareness of four different aspects of raising mindfulness:[21]

- the six sense-bases which one needs to be aware of (kāyānupassanā);

- contemplation on vedanās, which arise with the contact between the senses and their objects (vedanānupassanā);

- the altered states of mind to which this practice leads (cittānupassanā);

- the development from the five hindrances to the seven factors of enlightenment (dhammānupassanā).

Rupert Gethin notes that the contemporary Vipassana movement interprets the Satipatthana Sutta as "describing a pure form of insight (vipassanā) meditation" for which samatha (calm) and jhāna are not necessary. Yet, in pre-sectarian Buddhism, the establishment of mindfulness was placed before the practice of the jhanas, and associated with the abandonment of the five hindrances and the entry into the first jhana.[22][note 2]

According to Paul Williams, referring to Erich Frauwallner, mindfulness provided the way to liberation, "constantly watching sensory experience in order to prevent the arising of cravings which would power future experience into rebirths."[19][note 3] Buddhadasa also argued that mindfulness provides the means to prevent the arising of disturbing thought and emotions, which cause the further chain of reactions leading to rebirth of the ego and selfish thought and behavior.[23]

According to Vetter, dhyana may have been the original core practice of the Buddha, which aided the maintenance of mindfulness.[5]

Samprajaña, apramāda and atappa[edit]

Satii was famously translated as "bare attention" by Nyanaponika Thera. Yet, in Buddhist practice, "mindfulness" is more than just "bare attention"; it has the more comprehensive and active meaning of samprajaña, "clear comprehension," and apramāda, "vigilance".[24][note 4] All three terms are sometimes (confusingly) translated as "mindfulness", but they all have specific shades of meaning.

In a publicly available correspondence between Bhikkhu Bodhi and B. Alan Wallace, Bodhi has described Ven. Nyanaponika Thera's views on "right mindfulness" and sampajañña as follows:

In the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta, sati and sampajañña are combined with atappa (Pali; Sanskrit: ātapaḥ), or "ardency,"[note 6] and the three together comprise yoniso manasikara (Pali; Sanskrit: yoniśas manaskāraḥ), "appropriate attention" or "wise reflection."[26]

| English | Pali | Sanskrit/Nepali | Chinese | Tibetan |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mindfulness/awareness | sati | smṛti स्मृति | 念 (niàn) | trenpa (wylie: dran pa) |

| clear comprehension | sampajañña | samprajñāna संप्रज्ञान | 正知力 (zhèng zhī lì) | sheshin (wylie: shes bzhin) |

| vigilance/heedfulness | appamāda | apramāda अप्रमाद | 不放逸座 (bù fàng yì zuò) | bakyö (wylie: bag yod) |

| ardency | atappa | ātapaḥ आतप | 勇猛 (yǒng měng) | nyima (wylie: nyi ma) |

| attention/engagement | manasikāra | manaskāraḥ मनस्कारः | 如理作意 (rú lǐ zuò yì) | yila jeypa (wylie: yid la byed pa) |

| foundation of mindfulness | satipaṭṭhāna | smṛtyupasthāna स्मृत्युपासना | 念住 (niànzhù) | trenpa neybar zagpa (wylie: dran pa nye bar gzhag pa) |

Anapanasati - mindfulness of breathing[edit]

Ānāpānasati (Pali; Sanskrit: ānāpānasmṛti; Chinese: 安那般那; Pīnyīn: ānnàbānnà; Sinhala: ආනා පානා සති), meaning "mindfulness of breathing" ("sati" means mindfulness; "ānāpāna" refers to inhalation and exhalation), is a form of Buddhist meditation now common to the Tibetan, Zen, Tiantai, and Theravada schools of Buddhism, as well as western-based mindfulness programs. Anapanasati means to feel the sensations caused by the movements of the breath in the body, as is practiced in the context of mindfulness. According to tradition, Anapanasati was originally taught by the Buddha in several sutras including the Ānāpānasati Sutta.[note 7] (MN 118)

The Āgamas of early Buddhism discuss ten forms of mindfulness.[note 8] According to Nan Huaijin, the Ekottara Āgama emphasizes mindfulness of breathing more than any of the other methods, and provides the most specific teachings on this one form of mindfulness.[28]

Vipassanā - discriminating insight[edit]

Satipatthana, as four foundations of mindfulness, c.q. anapanasati, "mindfulness of breathing," is being employed to attain Vipassanā (Pāli), insight into the true nature of reality as impermanent and anatta, c.q. sunyata, lacking any permanent essence.[29][30]

In the Theravadin context, this entails insight into the three marks of existence, namely the impermanence of and the unsatisfactoriness of every conditioned thing that exists, and non-self. In Mahayana contexts, it entails insight into what is variously described as sunyata, dharmata, the inseparability of appearance and emptiness (two truths doctrine), clarity and emptiness, or bliss and emptiness.[31]

Vipassanā is commonly used as one of two poles for the categorization of types of Buddhist practice, the other being samatha (Pāli; Sanskrit: śamatha).[32] Though both terms appear in the Sutta Pitaka[note 9], Gombrich and Brooks argue that the distinction as two separate paths originates in the earliest interpretations of the Sutta Pitaka,[37] not in the suttas themselves.[38][note 10] Vipassana and samatha are described as qualities which contribute to the development of mind (bhāvanā). According to Vetter, Bronkhorst and Gombrich, discriminating insight into transiency as a separate path to liberation was a later development,[39][40][41] under pressure of developments in Indian religious thinking, which saw "liberating insight" as essential to liberation.[5] This may also have been due to an over-literal interpretation by later scholastics of the terminology used by the Buddha,[42] and to the problems involved with the practice of dhyana, and the need to develop an easier method.[43] According to Wynne, the Buddha combined meditative stabilisation with mindful awareness and "an insight into the nature of this meditative experience."[44]

Various traditions disagree which techniques belong to which pole.[45] According to the contemporary Theravada orthodoxy, samatha is used as a preparation for vipassanā, pacifying the mind and strengthening the concentration in order to allow the work of insight, which leads to liberation.

Vipassanā-meditation has gained popularity in the west through the modern Buddhist vipassana movement, modeled after Theravāda Buddhism meditation practices,[46] which employs vipassanā and ānāpāna (anapanasati, mindfulness of breathing) meditation as its primary techniques and places emphasis on the teachings of the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta.

Mindfulness (psychology)[edit]

Mindfulness practice, inherited from the Buddhist tradition, is being employed in psychology to alleviate a variety of mental and physical conditions, including obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety, and in the prevention of relapse in depression and drug addiction.[47]

"Bare attention"[edit]

Georges Dreyfus has expressed unease with the definition of mindfulness as "bare attention" or "nonelaborative, nonjudgmental, present-centered awareness", stressing that mindfulness in Buddhist context means also "remembering", which indicates that the function of mindfulness also includes the retention of information. Dreyfus concludes his examination by stating:

Robert H. Sharf notes that Buddhist practice is aimed at the attainment of "correct view", not just "bare attention":

Jay L. Garfield, quoting Shantideva and other sources, stresses that mindfulness is constituted by the union of two functions, calling to mind and vigilantly retaining in mind. He demonstrates that there is a direct connection between the practice of mindfulness and the cultivation of morality – at least in the context of Buddhism from which modern interpretations of mindfulness are stemming.[50]

See also[edit]

- Buddhism and psychology

- Buddhist meditation

- Dennis Lewis

- Eternal Now (New Age)

- Henepola Gunaratana

- John Garrie

- Mahasati Meditation

- Mahasi Sayadaw

- Metacognition

- Mindfulness (journal)

- Nepsis (Eastern Orthodox Christianity)

- S.N. Goenka

- Samu (Zen)

- Shinzen Young

- Taqwa and dhikr, related Islamic concepts

- Thich Nhat Hanh

- Vipassana

Notes[edit]

- ^ Quotes from Gethin, Rupert M.L. (1992), The Buddhist Path to Awakening: A Study of the Bodhi-Pakkhiȳa Dhammā. BRILL's Indological Library, 7. Leiden and New York: BRILL

- ^ Gethin: "The sutta is often read today as describing a pure form of insight (vipassanā) meditation that bypasses calm (samatha) meditation and the four absorptions (jhāna), as outlined in the description of the Buddhist path found, for example, in the Sāmaññaphala-sutta [...] The earlier tradition, however, seems not to have always read it this way, associating accomplishment in the exercise of establishing mindfulness with abandoning of the five hindrances and the first absorption."[22]

- ^ Frauwallner, E. (1973), History of Indian Philosophy, trans. V.M. Bedekar, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. Two volumes., pp.150 ff

- ^ [I]n Buddhist discourse, there are three terms that together map the field of mindfulness [...] [in their Sanskrit variants] smṛti (Pali: sati), samprajaña (Pali: Sampajañña) and apramāda (Pali: appamada).[24]

- ^ According to this correspondence, Ven. Nyanaponika spend his last ten years living with and being cared for by Bodhi. Bodhi refers to Nyanaponika as "my closest kalyāṇamitta in my life as a monk."

- ^ Dictionary.com:adjective

- having, expressive of, or characterized by intense feeling; passionate; fervent: an ardent vow; ardent love.

- intensely devoted, eager, or enthusiastic; zealous: an ardent theatergoer. an ardent student of French history.

- vehement; fierce: They were frightened by his ardent, burning eyes.

- burning, fiery, or hot: the ardent core of a star.

- ^ In the Pali canon, the instructions for anapanasati are presented as either one tetrad (four instructions) or four tetrads (16 instructions). The most famous exposition of four tetrads – after which Theravada countries have a national holiday (see uposatha) – is the Anapanasati Sutta, found in the Majjhima Nikaya (MN), sutta number 118 (for instance, see Thanissaro, 2006). Other discourses which describe the full four tetrads can be found in the Samyutta Nikaya's Anapana-samyutta (Ch. 54), such as SN 54.6 (Thanissaro, 2006a), SN 54.8 (Thanissaro, 2006b) and SN 54.13 (Thanissaro, 1995a). The one-tetrad exposition of anapanasati is found, for instance, in the Kayagata-sati Sutta (MN 119; Thanissaro, 1997), the Maha-satipatthana Sutta (DN 22; Thanissaro, 2000) and the Satipatthana Sutta (MN 10; Thanissaro, 1995b).

- ^ The Ekottara Āgama has:[27]

- mindfulness of the Buddha

- mindfulness of the Dharma

- mindfulness of the Sangha

- mindfulness of giving

- mindfulness of the heavens

- mindfulness of stopping and resting

- mindfulness of discipline

- mindfulness of breathing

- mindfulness of the body

- mindfulness of death

- ^ AN 4.170 (Pali):

“Yo hi koci, āvuso, bhikkhu vā bhikkhunī vā mama santike arahattappattiṁ byākaroti, sabbo so catūhi maggehi, etesaṁ vā aññatarena.

Katamehi catūhi? Idha, āvuso, bhikkhu samathapubbaṅgamaṁ vipassanaṁ bhāveti[...]

Puna caparaṁ, āvuso, bhikkhu vipassanāpubbaṅgamaṁ samathaṁ bhāveti[...]

Puna caparaṁ, āvuso, bhikkhu samathavipassanaṁ yuganaddhaṁ bhāveti[...]

Puna caparaṁ, āvuso, bhikkhuno dhammuddhaccaviggahitaṁ mānasaṁ hoti[...]

English translation:

Friends, whoever — monk or nun — declares the attainment of arahantship in my presence, they all do it by means of one or another of four paths. Which four?

There is the case where a monk has developed insight preceded by tranquility. [...]

Then there is the case where a monk has developed tranquillity preceded by insight. [...]

Then there is the case where a monk has developed tranquillity in tandem with insight. [...]

"Then there is the case where a monk's mind has its restlessness concerning the Dhamma [Comm: the corruptions of insight] well under control.[33]

AN 2.30 Vijja-bhagiya Sutta, A Share in Clear Knowing:

"These two qualities have a share in clear knowing. Which two? Tranquility (samatha) & insight (vipassana).

"When tranquility is developed, what purpose does it serve? The mind is developed. And when the mind is developed, what purpose does it serve? Passion is abandoned.

"When insight is developed, what purpose does it serve? Discernment is developed. And when discernment is developed, what purpose does it serve? Ignorance is abandoned.

"Defiled by passion, the mind is not released. Defiled by ignorance, discernment does not develop. Thus from the fading of passion is there awareness-release. From the fading of ignorance is there discernment-release."[34]

SN 43.2 (Pali): "Katamo ca, bhikkhave, asaṅkhatagāmimaggo? Samatho ca vipassanā".[35] English translation: "And what, bhikkhus, is the path leading to the unconditioned? Serenity and insight."[36] - ^ Brooks: "While many commentaries and translations of the Buddha's Discourses claim the Buddha taught two practice paths, one called "shamata" and the other called "vipassanā," there is in fact no place in the suttas where one can definitively claim that."[38]

References[edit]

- ^ "Sati". The Pali Text Society's Pali-English Dictionary. Digital Dictionaries of South Asia, University of Chicago. Archived from the original on 2012-12-12.

- ^ a b Sharf 2014, p. 942.

- ^ Sharf 2014, p. 943. "Even so, your Majesty, sati, when it arises, calls to mind dhammas that are skillful and unskillful, with faults and faultless, inferior and refined, dark and pure, together with their counterparts: these are the four establishings of mindfulness, these are the four right endeavors, these are the four bases of success, these are the five faculties, these are the five powers, these are the seven awakening-factors, this is the noble eight-factored path, this is calm, this is insight, this is knowledge, this is freedom. Thus the one who practices yoga resorts to dhammas that should be resorted to and does not resort to dhammas that should not be resorted to; he embraces dhammas that should be embraced and does not embrace dhammas that should not be embraced."

- ^ a b Sharf 2014, p. 943.

- ^ a b c Vetter 1988.

- ^ T. W. Rhys Davids, tr., 1881, Buddhist Suttas, Clarendon Press, p. 107.

- ^ D. J. Gogerly, "On Buddhism", Journal of the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1845, pp. 7-28 and 90-112.

- ^ Davids, 1881, p. 145.

- ^ The Wheel of the Law: Buddhism Illustrated From Siamese Sources by the Modern Buddhist, A Life of Buddha, and an Account of the Phrabat by Henry Alabaster, Trubner & Co., London: 1871 pg 197[1]

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed., 2002

- ^ Lecture, Stanford University Center for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education, c 18:03 [2] Archived November 20, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Interview with Bhikkhu Bodhi: Translator for the Buddha".

- ^ https://www.bps.lk/olib/bp/bp437s_Bodhi_Investigating-Dhamma.pdf[bare URL PDF]

- ^ Monier-Williams Online Dictionary. N.B.: these definitions are simplified and wikified.

- ^ Bernhard Karlgren, 1923, Analytic Dictionary of Chinese and Sino-Japanese, Paul Geunther, p. 207. Dover reprint.

- ^ William Edward Soothill and Lewis Hodous, 1937, A Dictionary of Chinese Buddhist Terms: with Sanskrit and English Equivalents and a Sanskrit-Pali Index[permanent dead link].

- ^ "Digital Dictionary of Buddhism".

- ^ James H. Austin (2014), Zen-Brain Horizons: Toward a Living Zen, MIT Press, p.83

- ^ a b Williams & Tribe 2000, p. 46.

- ^ Buddhadasa, Heartwood of the Bodhi-tree

- ^ Polak 2011.

- ^ a b Gethin, Rupert, Sayings of the Buddha: New Translations from the Pali Nikayas (Oxford World's Classics), 2008, p. 142.

- ^ Buddhadasa 2014, p. 78-80, 101-102, 117 (note 42).

- ^ a b "Friends of the Western Buddhist Order (FWBO): Buddhism and Mindfulness". madhyamavani.fwbo.org.

- ^ ""The Nature of Mindfulness and Its Role in Buddhist Meditation" A Correspondence between B.A. wallace and the Venerable Bikkhu Bodhi, Winter 2006, p.4" (PDF).

- ^ "Mindfulness Defined," by Thanissaro Bhikku. pg 2

- ^ Nan Huaijin. Working Toward Enlightenment: The Cultivation of Practice. York Beach: Samuel Weiser. 1993. pp. 118-119, 138-140.

- ^ Nan Huaijin. Working Toward Enlightenment: The Cultivation of Practice. York Beach: Samuel Weiser. 1993. p. 146.

- ^ Rinpoche, Khenchen Thrangu; Thrangu, Rinpoche (2004). Essentials of Mahamudra: Looking Directly at the Mind, by Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche. ISBN 978-0861713714.

- ^ Henepola Gunaratana, Mindfulness in plain English, Wisdom Publications, pg 21.

- ^ Defined by Reginald A. Ray. ""Vipashyana," by Reginald A. Ray. Buddhadharma: The Practitioner's Quarterly, Summer 2004". Archive.thebuddhadharma.com. Archived from the original on 2014-01-02. Retrieved 2013-05-30.

- ^ "What is Theravada Buddhism?". Access to Insight. Access to Insight. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ "AN 4.170 Yuganaddha Sutta: In Tandem. Translated from the Pali by Thanissaro Bhikkhu". Accesstoinsight.org. 2010-07-03. Retrieved 2013-05-30.

- ^ "AN 2.30 Vijja-bhagiya Sutta, A Share in Clear Knowing. Translated from the Pali by Thanissaro Bhikkhu". Accesstoinsight.org. 2010-08-08. Retrieved 2013-05-30.

- ^ "SN 43.2". Agama.buddhason.org. Retrieved 2013-05-30.

- ^ Bikkhu Bodhi, The Connected Discourses of the Buddha, p. 1373

- ^ Gombrich 1997, p. 96-144.

- ^ a b Brooks 2006.

- ^ Vetter 1988, p. xxxiv–xxxvii.

- ^ Bronkhorst 1993.

- ^ Gombrich 1997, p. 131.

- ^ Gombrich 1997, p. 96-134.

- ^ Vetter 1988, p. xxxv.

- ^ Wynne, Alexander (2007). "Conclusion". The Origin of Buddhist Meditation. Routledge. pp. 94–95. ISBN 978-1134097401.

At least we can say that liberation, according to the Buddha, was not simply a meditative experience but an insight into meditative experience. The Buddha taught that meditation must be accompanied by a careful attention to the basis of one’s experience—the sensations caused by internal and external objects - and eventually an insight into the nature of this meditative experience. The idea that liberation requires a cognitive act of insight went against the grain of Brahminic meditation, where it was thought that the yogin must be without any mental activity at all, 'like a log of wood'.

- ^ Schumann 1974.

- ^ McMahan 2008.

- ^ Siegel, D. J. (2007). "Mindfulness training and neural integration: Differentiation of distinct streams of awareness and the cultivation of well-being". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2 (4): 259–63. doi:10.1093/scan/nsm034. PMC 2566758.

- ^ "Is Mindfulness Present-Centered and Nonjudgmental? A Discussion of the Cognitive Dimensions of Mindfulness" by Georges Dreyfus

- ^ "» Geoffrey Samuel Transcultural Psychiatry".

- ^ "Mindfulness and Ethics: Attention, Virtue and Perfection" by Jay Garfield

Sources[edit]

- Buddhadasa (2014). Heartwood of the Bodhi Tree. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 978-1-61429-152-7.

- Boccio, Frank Jude (2004). Mindfulness yoga: the Awakened Union of Breath, Body and Mind (1st ed.). Boston: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-335-4.

- Brahmavamso (2006). Mindfulness, Bliss, and Beyond: A Meditator's Handbook. Boston: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 978-0-86171-275-5.

- Bronkhorst, Johannes (1993), The Two Traditions Of Meditation In Ancient India, Motilal Banarsidass Publ.

- Brooks, Jeffrey S. (2006), A Critique of the Abhidhamma and Visuddhimagga

- Gombrich, Richard F. (1997), How Buddhism Began. The Conditioned Genesis of the Early Teachings, New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

- Guenther, Herbert V.; Kawamura, Leslie S. (1975). Mind in Buddhist Psychology: A Translation of Ye-shes rgyal-mtshan's "The Necklace of Clear Understanding" (Kindle ed.). Dharma Publishing.

- Gunaratana, Henepola (2011). Mindfulness in Plain English (20th Anniversary ed.). Boston: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 978-0-86171-906-8.

- Hanh, Thich Nhat (1996). The Miracle of Mindfulness: A Manual on Meditation. Beacon Press.

- Hoopes, Aaron (2007). Zen Yoga: A Path to Enlightenment through Breathing, Movement and Meditation. Kodansha International.

- McMahan, David L. (2008), The Making of Buddhist Modernism, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195183276

- Polak, Grzegorz (2011). Reexamining Jhana: Towards a Critical Reconstruction of Early Buddhist Soteriology. UMCS.

- Sharf, Robert (2014). "Mindfulness and Mindlessness in Early Chan" (PDF). Philosophy East and West. 64 (4): 933–964. doi:10.1353/pew.2014.0074. ISSN 0031-8221. S2CID 144208166.

- Schumann, Hans Wolfgang (1974), Buddhism: an outline of its teachings and schools, Theosophical Pub. House

- Siegel, Ronald D. (2010). The Mindfulness Solution: Everyday Practices for Everyday Problems. New York: Guilford Press. ISBN 978-1-60623-294-1.

- Vetter, Tilmann (1988). The Ideas and Meditative Practices of Early Buddhism. BRILL.

- Weiss, Andrew (2004). Beginning Mindfulness: Learning the Way of Awareness. New World Library.

- Williams, Paul; Tribe, Anthony (2000). Buddhist Thought: a Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-20700-2.

External links[edit]

| Look up 念 in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Mindfulness Research Guide at the American Mindfulness Research Association. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- Oxford University Mindfulness Research Centre. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- What is Mindfulness? Buddhism for Beginners