Blood Brothers: the friendship and fallout of Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali

In a new Netflix documentary, film-maker Marcus A Clarke explores the relationship between the two civil rights figures

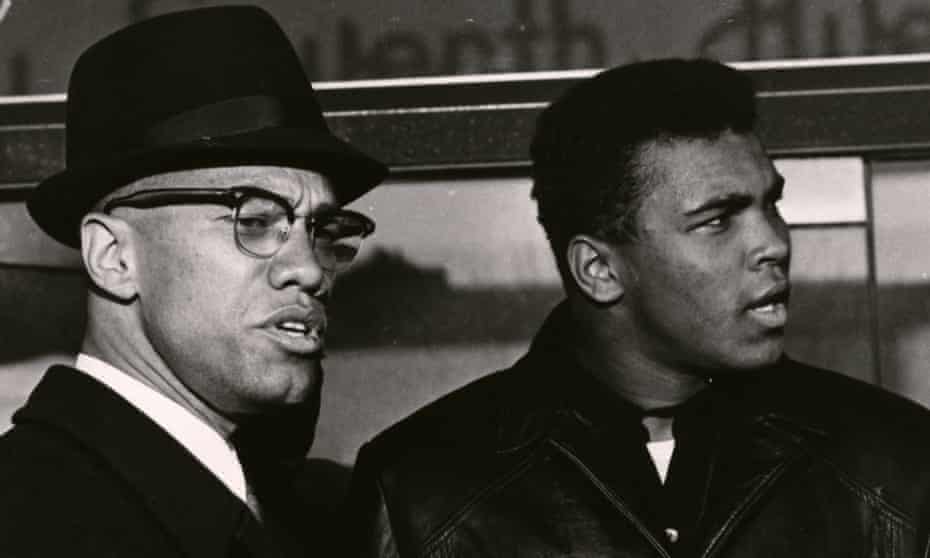

Malcolm X & Muhammad Ali Photograph: Netflix

Malcolm X & Muhammad Ali Photograph: NetflixRadheyan Simonpillai

Thu 9 Sep 2021 16.16 AEST

Blood Brothers’ director, Marcus A Clarke, wants to show us a side of Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali that we’re not familiar with, which is a considerable challenge. The two civil rights icons are the subjects of multiple biographies and documentaries, not to mention biopics directed by legends like Spike Lee (Malcolm X) and Michael Mann (Ali). And they were recently portrayed getting spirited and sentimental together in Regina King’s Oscar-nominated film One Night In Miami.

‘My dad’s movement is coming full circle’: Rasheda Ali on a boxing legacy

Read more

But in his Netflix documentary, Clarke digs further into the men and their environment, with archival material and first-hand accounts from X’s daughter Ilyasah Shabazz, Ali’s younger brother Rahman and several others who knew them or understood the political and social environment they were up against.

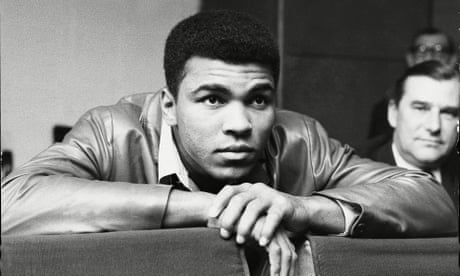

We get a sense of Malcolm X’s ferocity with words but also his tenderness and vulnerability among brethren. And then there’s Muhammad Ali: he had a loud mouth too, but as heavyweight champion, he made the world shake with his rock-hard fists. He was also a soft sponge when it came to learning from a spiritual father figure and friend like X. “There’s just this admiration and joy being shared between the two of them,” Clarke told the Guardian over a Zoom call from his LA home. “And that’s something I don’t think people have necessarily seen before.”

Blood Brothers, which is produced by the creator of Black-ish, Kenya Barris, adapts Randy Roberts and Johnny Smith’s book about X and Ali’s relationship, drawn from heavy research into past biographies, documents and FBI surveillance records. Roberts and Smith also appear in the film. And in an era where authorship and identity packs so much meaning and implication, I’d be remiss if I didn’t point out that the two authors are white.

“Whether they’re white or Black, there’s a lot of value in the research,” says Clarke, who was born in Brooklyn to Jamaican parents. Clarke adds that he saw an opportunity to balance the scholarly work of Roberts and Smith with more intimate accounts from those close to X and Ali, while exploring social and cultural details that the book doesn’t consider to the same extent.

If Roberts and Smith’s book connected the dots to give the relationship between X and Ali shape, Clarke’s documentary colours it all in with an understanding of what it means to be Black in America. He latches on to how Muhammad Ali, who was then known as Cassius Clay, would have been affected in transformative ways by the lynching of Emmett Till, comparing that experience to how Black youth today respond to images of police brutality. The documentary also presents details about Malcolm X’s parents, who followed Marcus Garvey. The Black nationalist leader’s Pan-African movement is echoed in X’s own principles, treating Black and brown oppression as a global issue. “These are at the foundation of who he was,” says Clarke.

There are also musical asides in the doc, which home in on how Bob Marley’s sounds figured into the movement, or how the Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan had a career as a calypso singer under the moniker The Charmer. Such details may seem out of place in a doc about X and Ali, but they are part of the cultural fabric that would nurture and inspire the activists. “I tend to believe that our film has a great deal of soul for that reason,” says Clarke. “For Black people, music and storytelling have always been symbiotic. For so long our history has been told through song. Messages have been put into song.”

I can’t help but pay attention to the wall behind Clarke showing off a telling curation of personal history and popular culture. There’s a Warhol-like poster of Marilyn Monroe and another from the movie Attack of the 50 Foot Woman. Both flank a large print of Sunday’s Best, the 1941 photograph of young Black boys in Chicago’s South Side sitting on a Pontiac while dressed to attend church for Easter. That print is mounted just above a framed ticket to the first inauguration of Barack Obama, who spent his formative years on Chicago’s South Side. All of that sits above a framed photo of the director’s grandmother.

I’m scouring these details on the wall, in the same way the filmmaker wades through those cultural signifiers in X and Ali’s own life, hoping to arrive at some deeper understanding into the influences on his work, which tends to mine the intersection between popular culture and social activism.

Clarke got his start as a teenage intern and then production assistant for a company that made television commercials for brands like Pizza Hut and Danone. He worked on the kind of spots where warm cheese stretches in slow motion, or a candy bar splashes in a pillowy pool of chocolate. “Basically I worked for Willy Wonka,” says Clarke. He was also often the only Black person in the room or on set at a time when no one was pushing to diversify the talent behind the camera.

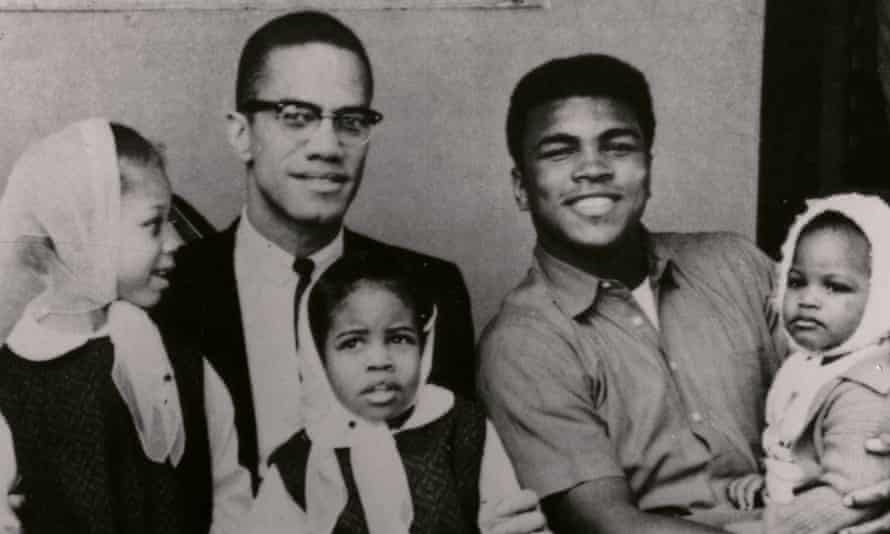

Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali with their children Photograph: Netflix

Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali with their children Photograph: NetflixAfter Eric Garner’s death in police restraint, Clarke grabbed what resources he had to go out on the street and document the Black Lives Matter protests shutting down New York City, the material becoming one of his first shorts: 2014’s I Can’t Breathe. “That opened up the lane of possibilities for how I can start to fuse more messaging and really say something with the films that I was doing,” says Clarke.

He went on to explore southern rap’s social underpinnings in the Mass Appeal short Trap City and followed rapper TI on a political and activist journey in an episode of Netflix’s hip-hop doc series Rapture. And then he came to Blood Brothers, retelling the story of Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali at a time when the potency of their activism speaks to the overwhelming pain and anger following George Floyd’s murder.

Malcolm X’s words resonate today, says Clarke. He also sees a lesson to be learned from the leader’s tragic fallout with Ali. Clarke’s documentary gets into the outside forces and pressures that caused the fissure between X and Ali, subversive influences which the director points out are still at work today. Consider the scrutiny at Black Lives Matter over how resources are allocated, the disinformation spread about protesters by the far right and the FBI surveillance on Black activists echoing the agency’s Cointelpro tactics to disrupt social movements.

“People who are Black and brown, who are trying to achieve something, who have a mission, who feel like they have a purpose towards something, have to keep in mind that there’s always going to be forces at work trying to slow them, stop them or divide them,” says Clarke.

“We need more solidarity. This is what Malcolm was about. We have the same mission. Whether you’re in America, Africa, or the Caribbean, wherever Black and brown people are, we’re facing the same oppression.”

Blood Brothers is now available on Netflix