쇼와 국가주의

| 이 글의 정확성과 사실 여부에 대해 논란이 있습니다. (2021년 4월 10일) |

쇼와 국가주의(일본어:

일본에서는 천황제 파시즘(일본어:

배경[편집]

청일전쟁과 러일전쟁의 승리로 일본 제국은 서구 제국주의 열강의 반열에 합류했다. 일본은 19세기에 서방 국가들이 강제한 불평등조약들을 개정하기 위해서는 자신들도 서방 국가들처럼 식민제국을 수립하고 그것을 유지하기 위한 강력한 군사력이 필요하다고 판단했다.

자유민권운동과 다이쇼 데모크라시로 일본은 자유민주주의 체제가 수립되었지만, 민주주의는 재벌이 사회 자본을 독점한 정치경제적 상황의 해결에 무능을 나타냈다. 이에 환멸한 사람들에게 군부가 부패한 정치꾼들의 대안으로 조명되었다. 군부는 민주주의 내각이 군비를 제한하고 군을 통제하려 하는 것을 국가안보에 대한 위협으로 판단했고, 군사력 확충을 위해 국가가 산업을 직접 통제하는 것을 선호했다. 또한 좌익사상의 발흥을 막기 위한 국가주도의 사회복지에도 관심이 있었다.

사실 재벌의 독점체제는 메이지 시대에 급속한 경제성장을 추구하는 과정에서 국가가 조장한 것이었다. 이것을 국가가 주도해서 재편하는 과정은 유럽 파시즘의 코포라티즘 정격과 피상적 유사성이 있다.

쇼와 시대의 발전[편집]

천황제 파시즘론[편집]

일본의 천황제 파시즘론은 전후민주주의 사상가인 마루야마 마사오가 1946년 발표한 『초국가주의의 논리와 심리』를 기원으로 한다.[1] 마루야마는 여기서 파시즘을 “반혁명의 가장 첨단적이고 가장 전투적인 형태”라고 정의하고,[2] 이탈리아 파시즘과 독일의 나치즘은 의회제 사회의 대중운동에 의한 “아래로부터의 파시즘”이었지만, 일본의 파시즘은 군부와 관료가 주도한 “위로부터의 파시즘”이라고 규정했다.[3] 이로부터 1970년대까지 마루야마를 따르는 시각이 대세가 되었다.[4][5][6]

천황제 파시즘론에 따르면, 천황제 파시즘은 다음 세 단계에 걸쳐 형성되었다.[7]

- 준비기(準備期): 제1차 세계대전부터 만주사변까지로, “민간우익운동시대”. 연대로는 다이쇼 8년(1919년)에서 쇼와 6년(1931년)까지.

- 성숙기(成熟期): 만주사변부터 2.26 사건까지로, 민간우익운동세력이 군부 일부와 결탁해 파시즘 운동의 추진력으로 국정 중심을 차지하게 된 시기. 3월사건, 혈맹단사건, 5.16 사건, 신병대사건, 사관학교사건, 아이자와 사건, 그리고 절정인 2.26 사건에 이르기까지 파쇼 테러리즘이 빈발한 시기. 연대로는 쇼와 6년(1931년)-쇼와 11년(1936년)까지

- 완성시기(完成時期): 관료・중신 등 반(半)봉건적 세력과 독점자본과 부르주아 정당 사이에서 군부가 불충분하지만 연합지배체제를 형성한 시기. 연대적으로는 쇼와 11년(1936년)-쇼와 20년(1945년)까지.

천황제 파시즘 긍정론[편집]

- 미와 야스후미는 저서 『일본 파시즘과 노동운동』에서 이런 견해를 밝혔다. 1935년을 분수령으로 경찰정신(警察精神)의 작흥이 진행되어 노사관계・시민생활에 경찰의 개입이 심화되었다. 경찰은 탄압 뿐 아니라 사회적 서체율의 조정・통합・민중동원의 기능을 했다. 즉 이탈리아와 독일에서 파시스트 대중조직이 맡았던 역할을 경찰이 맡았다. 일본의 “아래로부터의” 파시즘은 군부, 관리 등 기성권력에 의존적인 특질을 가지고 있었다.[8]

- 마츠우라 츠토무는 저서 『일본 파시즘의 전쟁교육체제와 융화교육』에서 이런 견해를 밝혔다. 1942년 8월 문부성 사회교육국이 『국민동화에의 길』을 간행할 때 비로소 정부의 교육방침으로 동화교육 정책의 이념과 구체적 방침을 밝혔다. 이 책은 피차별부락의 아동과 청년을 동화교육을 통해 “황국민의 순진한 자각을 세우고 고뇌와 간난을 참고 신도(臣道)의 실천에 매진하는 강건한 심신”을 가지도록 “도야・단동”하는 것을 목표로 삼았다. 이는 수평사의 “아래로부터의” 운동에너지를 이용해 부락아동 및 청년을 도야시키는 것을 제시한 것이라고 보고, 이 동화교육 지침을 "천황제 파시즘" 교육의 극한형태로 파악하려는 학설이다.[9]

- 스사키 신이치는 저서 『일본 파시즘과 그 시대』에서 “양상의 차이를 가지고 일본을 파시즘이 아니라고 할 수는 없다. 동종의 국가체제라도 나라와 민족의 역사적 전통과 환경 등에 의해 다양한 변형을 가지게 됨이 극히 당연”하기 때문이라고 말했다.[10]

천황제 파시즘 부정론[편집]

- 케빈 마이클 도크, 그레고리 카스자, 로버트 팩스턴 등 서양 학자들은 일본 제국이 보수적 독재일 뿐 파시즘은 아니었다고 본다. 도크에 따르면 메이지 헌법을 지키기 위한 목적으로 일본제국 정부가 탄압한 반체제파에는 극좌 뿐 아니라 극우도 포함되어 있다.[11] 천황제 파시즘론에서는 5.15 사건과 2.26 사건이 실패했지만 그것이 군부가 정부를 장악하는 계기가 되었다고 말하는데, 팩스턴에 따르면 이것은 무솔리니나 히틀러가 진압됨으로써 이탈리아와 독일에 파시즘 정권이 세워졌다는 황당한 주장이 된다.[12]

- 코민테른과 카미야마 시게오의 견해로도 당시의 일본 정치체제는 “군사적・봉건적 제국주의”일 뿐, 파시즘이라고 볼 수 없다. 군사적 봉건적 제국주의란 유럽 선진국의 제국주의와, 제정 러시아의 제국주의를 구분하여 후자를 지칭한 레닌의 용어다. 일본공산당의 강령에서도 이를 따라 “일본제국주의”라는 말로 통일하고 있다.[13]

- 후루카와 타카히사는 저서 『쇼와전중기의 의회와 행정』에서 이런 견해를 밝혔다. 국체명징성명에서 일본의 국체는 천손강림 때 하사된 신의 칙명에 의한 만세일계의 것으로 주장되었으며, 여기에는 자유주의와 사회주의 뿐 아니라 파시즘도 외래사상으로 규정해 배제하려는 의도가 존재했다. 실제로 관념우익이 파시즘을 지지하는 혁신우익을 공격할 때도 이런 논리를 사용했다.[14]

- 재일 조선인 정치학자 강상중은 전전 일본은 파시즘처럼 단결하는 것이 아니라, 내부적으로 섹셔널리즘(부서할거주의) 경향이 강했다면서 나치 독일과 크게 달랐다고 지적했다.[15]

- 이토 타카시는 일본 파시즘이라는 개념의 유행은 극동국제군사재판이 제2차 세계대전을 파시즘 대 민주주의의 싸움으로 이념화한 것에서 비롯되었으며, 이 논리가 일본공산당이 내건 “반전 반파시즘”과도 친밀성이 있었기 때문에 강좌파 마르크시즘의 영향을 받은 전후 일본 주류 역사학계에서 당연하다는 듯 전전 일본 체제를 파시즘이라고 규정한 것이라 평했다.[16]

각주[편집]

- ↑ 初出:『世界』1946年5月号。所収:『現代政治の思想と行動』(上)、未來社、1956年12月。

- ↑ この定義、丸山眞男著『[新装版]現代政治の思想と行動』未来社 2006年 所収の同論文(11-28ページ)に書かれていませんでした。孫引の場合出典を変更してください。

- ↑ 丸山眞男と歴史の見方 Archived 2013년 6월 5일 - 웨이백 머신(山口定、2000年3月、政策科学7-3)

- ↑ 『万有百科大事典』第11巻、小学館、1973年、494頁

- ↑ 天皇制ファシズム論(中村菊男)

- ↑ 日本ファシズム研究序說(安部博純)

- ↑ 丸山眞男「日本ファシズムの思想と運動」(丸山眞男著 『[新装版] 現代政治の思想と行動』 未来社 2006年 所収 32ページ)

- ↑ 三輪泰史『日本ファシズムと労働運動』校倉書房、1988年。

- ↑ 松浦勉「日本ファシズムの戦争教育体制と融和教育」日本教育学会『日本教育学会大会発表要旨集録』1991年8月28日参照。

- ↑ 「日本ファシズムとその時代」(須崎愼一、大月書店、1998年、382p)

- ↑ Doak, Kevin (2009). 〈Fascism Seen and Unseen〉. Tansman, Alan. 《The culture of Japanese fascism》. Durham: Duke University Press. 44쪽. ISBN 0822344521.

Careful attention to the history of the Special Higher Police, and particularly to their use by Prime Minister Tōjō Hideki against his enemies even further to his political right, reveals that extreme rightists, fascists, and practically anyone deemed to pose a threat to the Meiji constitutional order were at risk.

- ↑ 로버트 팩스턴 (2005년 1월 10일). 《파시즘: 열정과 광기의 정치혁명》. 교양인. ISBN 9788995530054.

- ↑ 日本共産党綱領 - 2004年1月17日 第23回党大会で改定

- ↑ 古川隆久『昭和戦中期の議会と行政』(吉川弘文館、2005年)

- ↑ “台湾は親日的なのに、韓国が反日的なのはなぜか? 明治初期の「バグ」が一因に 〈AERA〉”. 《AERA dot. (アエラドット)》 (일본어). 20190927T113000+0900. 2019년 9월 27일에 확인함.

- ↑ 大塚健洋『大川周明』

Statism in Shōwa Japan

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| Part of a series on |

| Statism in Shōwa Japan |

|---|

|

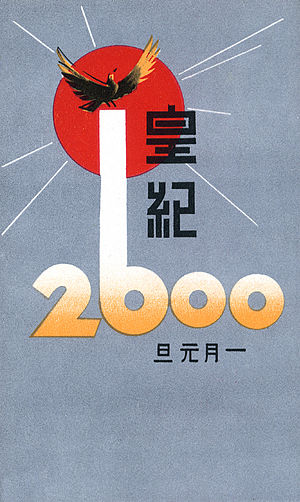

Statism (國家主義, Kokka Shugi)[a] was a political syncretism of extreme political ideologies in Japan, developed over a period of time from the Meiji Restoration. It is sometimes also referred to as Emperor-system fascism (天皇制ファシズム, Tennosei Fascism),[1] Japanese fascism (日本のファシズム, Nihon no Fascism) or Shōwa nationalism.

This movement dominated Japanese politics during the first part of the Shōwa period (reign of Emperor Hirohito). It was a mixture of ideas such as Japanese ultranationalism, militarism, fascism, and state capitalism, that were proposed by several contemporary political philosophers and thinkers in Japan.

Origins[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Fascism |

|---|

|

With a more aggressive foreign policy, and victory over China in the First Sino-Japanese War and over Imperial Russia in the Russo-Japanese War, Japan joined the Western imperialist powers. The need for a strong military to secure Japan's new overseas empire was strengthened by a sense that only through a strong military would Japan earn the respect of Western nations, and thus revision of the "unequal treaties" imposed in the 1800s.

The Japanese military viewed itself as "politically clean" in terms of corruption, and criticized political parties under a liberal democracy as self-serving and a threat to national security by their failure to provide adequate military spending or to address pressing social and economic issues. The complicity of the politicians with the zaibatsu corporate monopolies also came under criticism. The military tended to favour dirigisme and other forms of direct state control over industry, rather than free-market capitalism, as well as greater state-sponsored social welfare, to reduce the attraction of socialism and communism in Japan.

The special relation of militarists and the central civil government with the Imperial Family supported the important position of the Emperor as Head of State with political powers and the relationship with the nationalist right-wing movements. However, Japanese political thought had relatively little contact with European political thinking until the 20th century.

Under this ascendancy of the military, the country developed a very hierarchical, aristocratic economic system with significant state involvement. During the Meiji Restoration, there had been a surge in the creation of monopolies. This was in part due to state intervention, as the monopolies served to allow Japan to become a world economic power. The state itself owned some of the monopolies, and others were owned by the zaibatsu. The monopolies managed the central core of the economy, with other aspects being controlled by the government ministry appropriate to the activity, including the National Central Bank and the Imperial family. This economic arrangement was in many ways similar to the later corporatist models of European fascists.

During the same period, certain thinkers with ideals similar to those from shogunate times developed the early basis of Japanese expansionism and Pan-Asianist theories. Such thought later was developed by writers such as Saneshige Komaki into the Hakkō ichiu, Yen Block, and Amau doctrines.[2]

Developments in the Shōwa era[edit]

International Policy[edit]

The 1919 Treaty of Versailles did not recognize the Empire of Japan's territorial claims, and international naval treaties between Western powers and the Empire of Japan (Washington Naval Treaty and London Naval Treaty) imposed limitations on naval shipbuilding which limited the size of the Imperial Japanese Navy at a 10:10:6 ratio. These measures were considered by many in Japan as the refusal by the Occidental powers to consider Japan an equal partner. The latter brought about the May 15 incident.

Based on national security, these events released a surge of Japanese nationalism and ended collaboration diplomacy which supported peaceful economic expansion. The implementation of a military dictatorship and territorial expansionism were considered the best ways to protect the Yamato-damashii.

Civil discourse on statism[edit]

In the early 1930s, the Ministry of Home Affairs began arresting left-wing political dissidents, generally to extract a confession and renouncement of anti-state leanings. Over 30,000 such arrests were made between 1930 and 1933. In response, a large group of writers founded a Japanese branch of the International Popular Front Against Fascism and published articles in major literary journals warning of the dangers of statism. Their periodical, The People's Library (人民文庫), achieved a circulation of over five thousand and was widely read in literary circles, but was eventually censored, and later dismantled in January 1938.[3]

Works of Ikki Kita[edit]

Ikki Kita was an early 20th-century political theorist, who advocated a hybrid of statism with "Asian nationalism", which thus blended the early ultranationalist movement with Japanese militarism. His political philosophy was outlined in his thesis Kokutairon and Pure Socialism of 1906 and An Outline Plan for the Reorganization of Japan (日本改造法案大綱 Nihon Kaizō Hōan Taikō) of 1923. Kita proposed a military coup d'état to replace the existing political structure of Japan with a military dictatorship. The new military leadership would rescind the Meiji Constitution, ban political parties, replace the Diet of Japan with an assembly free of corruption, and would nationalize major industries. Kita also envisioned strict limits to private ownership of property, and land reform to improve the lot of tenant farmers. Thus strengthened internally, Japan could then embark on a crusade to free all of Asia from Western imperialism.

Although his works were banned by the government almost immediately after publication, circulation was widespread, and his thesis proved popular not only with the young officer class excited at the prospects of military rule and Japanese expansionism but with the populist movement for its appeal to the agrarian classes as well.

Works of Shūmei Ōkawa[edit]

Shūmei Ōkawa was a right-wing political philosopher, active in numerous Japanese nationalist societies in the 1920s. In 1926, he published Japan and the Way of the Japanese (日本及び日本人の道, Nihon oyobi Nihonjin no michi), among other works, which helped popularize the concept of the inevitability of a clash of civilizations between Japan and the west. Politically, his theories built on the works of Ikki Kita, but further emphasized that Japan needed to return to its traditional kokutai traditions to survive the increasing social tensions created by industrialization and foreign cultural influences.

Works of Sadao Araki[edit]

Sadao Araki was a noted political philosopher in the Imperial Japanese Army during the 1920s, who had a wide following within the junior officer corps. Although implicated in the February 26 Incident, he went on to serve in numerous influential government posts, and was a cabinet minister under Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe.

The Japanese Army, already trained along Prussian lines since the early Meiji period, often mentioned the affinity between yamato-damashii and the "Prussian Military Spirit" in pushing for a military alliance with Italy and Germany along with the need to combat Marxism. Araki's writing is imbued with nostalgia towards the military administrative system of the former shogunate, in a similar manner to which the National Fascist Party of Italy looked back to the ancient ideals of the Roman Empire or the NSDAP in Germany recalled an idealized version of First Reich and the Teutonic Order.

Araki modified the interpretation of the bushido warrior code to seishin kyōiku ("spiritual training"), which he introduced to the military as Army Minister, and the general public as Education Minister, and in general brought the concepts of the Showa Restoration movement into mainstream Japanese politics.

Some of the distinctive features of this policy were also used outside Japan. The puppet states of Manchukuo, Mengjiang, and the Wang Jingwei Government were later organized partly following Araki's ideas. In the case of Wang Jingwei's state, he himself had some German influences—prior to the Japanese invasion of China, he met with German leaders and picked up some fascist ideas during his time in the Kuomintang. These, he combined with Japanese militarist thinking. Japanese agents also supported local and nationalist elements in Southeast asia and White Russian residents in Manchukuo before war broke out.

Works of Seigō Nakano[edit]

Seigō Nakano sought to bring about a rebirth of Japan through a blend of the samurai ethic, Neo-Confucianism, and populist nationalism modelled on European fascism. He saw Saigō Takamori as epitomizing the 'true spirit' of the Meiji ishin, and the task of modern Japan to recapture it.

Shōwa Restoration Movement[edit]

Ikki Kita and Shūmei Ōkawa joined forces in 1919 to organize the short-lived Yūzonsha, a political study group intended to become an umbrella organization for the various right-wing statist movements. Although the group soon collapsed due to irreconcilable ideological differences between Kita and Ōkawa, it served its purpose in that it managed to join the right-wing anti-socialist, Pan-Asian militarist societies with centrist and left-wing supporters of a strong state.

In the 1920s and 1930s, these supporters of Japanese statism used the slogan Showa Restoration (昭和維新, Shōwa isshin), which implied that a new resolution was needed to replace the existing political order dominated by corrupt politicians and industrialists, with one which (in their eyes), would fulfil the original goals of the Meiji Restoration of direct Imperial rule via military proxies.

However, the Shōwa Restoration had different meanings for different groups. For the radicals of the Sakurakai, it meant the violent overthrow of the government to create a national syndicalist state with more equitable distribution of wealth and the removal of corrupt politicians and zaibatsu leaders. For the young officers, it meant a return to some form of "military-shogunate" in which the emperor would re-assume direct political power with dictatorial attributes, as well as divine symbolism, without the intervention of the Diet or liberal democracy, but who would effectively be a figurehead with day-to-day decisions left to the military leadership.

Another point of view was supported by Prince Chichibu, a brother of Emperor Shōwa, who repeatedly counselled him to implement a direct imperial rule, even if that meant suspending the constitution.[4]

In principle, some theorists proposed Shōwa Restoration, the plan of giving direct dictatorial powers to the Emperor (due to his divine attributes) for leading the future overseas actions in mainland Asia. This was the purpose behind the February 26 Incident and other similar uprisings in Japan. Later, however, these previously mentioned thinkers decided to organize their own political clique based on previous radical, militaristic movements in the 1930s; this was the origin of the Kodoha party and their political desire to take direct control of all the political power in the country from the moderate and democratic political voices.

Following the formation of this "political clique", there was a new current of thought among militarists, industrialists and landowners that emphasized a desire to return to the ancient shogunate system, but in the form of a modern military dictatorship with new structures. It was organized with the Japanese Navy and Japanese Army acting as clans under command of a supreme military native dictator (the shōgun) controlling the country. In this government, the Emperor was covertly reduced in his functions and used as a figurehead for political or religious use under the control of the militarists.[citation needed]

The failure of various attempted coups, including the League of Blood Incident, the Imperial Colors Incident and the February 26 Incident, discredited supporters of the Shōwa Restoration movement, but the concepts of Japanese statism migrated to mainstream Japanese politics, where it joined with some elements of European fascism.

Comparisons with European fascism[edit]

Early Shōwa statism is sometimes given the retrospective label "fascism", but this was not a self-appellation. When authoritarian tools of the state such as the Kempeitai were put into use in the early Shōwa period, they were employed to protect the rule of law under the Meiji Constitution from perceived enemies on both the left and the right.[5]

Some ideologists, such as Kingoro Hashimoto, proposed a single-party dictatorship, based on populism, patterned after the European fascist movements. An Investigation of Global Policy with the Yamato Race as Nucleus shows the influence clearly.[6]

These geopolitical ideals developed into the Amau Doctrine (天羽声明, an Asian Monroe Doctrine), stating that Japan assumed total responsibility for peace in Asia, and can be seen later when Prime Minister Kōki Hirota proclaimed justified Japanese expansion into northern China as the creation of "a special zone, anti-communist, pro-Japanese and pro-Manchukuo" that was a "fundamental part" of Japanese national existence.

Although the reformist right-wing, kakushin uyoku, was interested in the concept, the idealist right-wing, or kannen uyoku, rejected fascism as they rejected all things of western origin.[citation needed]

Because of the mistrust of unions in such unity, the Japanese went to replace them with "councils" (経営財団, keiei zaidan, lit. "management foundations", shortened: 営団 eidan) in every factory, containing both management and worker representatives to contain conflict.[7] This was part of a program to create a classless national unity.[8] The most famous of the councils is the Teito Rapid Transit Authority (帝都高速度交通営団, Teito Kōsoku-do Kōtsū Eidan, lit. "Imperial Capital Highspeed Transportation Council", TRTA), which survived the dismantling of the councils under the US-led Allied occupation. The TRTA is now the Tokyo Metro.

Kokuhonsha[edit]

The Kokuhonsha was founded in 1924 by conservative Minister of Justice and President of the House of Peers Hiranuma Kiichirō.[9] It called on Japanese patriots to reject the various foreign political "-isms" (such as socialism, communism, Marxism, anarchism, etc.) in favor of a rather vaguely defined "Japanese national spirit" (kokutai). The name "kokuhon" was selected as an antithesis to the word "minpon", from minpon shugi, the commonly-used translation for the word "democracy", and the society was openly supportive of totalitarian ideology.[10]

Divine Right and Way of the Warrior[edit]

One particular concept exploited was a decree ascribed to the legendary first emperor of Japan, Emperor Jimmu, in 660 BC: the policy of hakkō ichiu (八紘一宇, all eight corners of the world under one roof).[11]

This also related to the concept of kokutai or national polity, meaning the uniqueness of the Japanese people in having a leader with spiritual origins.[6] The pamphlet Kokutai no Hongi taught that students should put the nation before the self, and that they were part of the state and not separate from it.[12] Shinmin no Michi enjoined all Japanese to follow the central precepts of loyalty and filial piety, which would throw aside selfishness and allow them to complete their "holy task."[13]

The bases of the modern form of kokutai and hakkō ichiu were to develop after 1868 and would take the following form:

- Japan is the centre of the world, with its ruler, the Tennō (Emperor), a divine being, who derives his divinity from ancestral descent from the great Amaterasu-Ōmikami, the Goddess of the Sun herself.

- The Kami (Japan's gods and goddesses) have Japan under their special protection. Thus, the people and soil of Dai Nippon and all its institutions are superior to all others.

- All of these attributes are fundamental to the Kodoshugisha (Imperial Way) and give Japan a divine mission to bring all nations under one roof, so that all humanity can share the advantage of being ruled by the Tenno.

The concept of the divine Emperors was another belief that was to fit the later goals. It was an integral part of the Japanese religious structure that the Tennō was divine, descended directly from the line of Ama-Terasu (or Amaterasu, the Sun Kami or Goddess).

The final idea that was modified in modern times was the concept of Bushido. This was the warrior code and laws of feudal Japan, that while having cultural surface differences, was at its heart not that different from the code of chivalry or any other similar system in other cultures. In later years, the code of Bushido found a resurgence in belief following the Meiji Restoration. At first, this allowed Japan to field what was considered one of the most professional and humane militaries in the world, one respected by friend and foe alike.[citation needed] Eventually, however, this belief would become a combination of propaganda and fanaticism that would lead to the Second Sino-Japanese War of the 1930s and World War II.

It was the third concept, especially, that would chart Japan's course towards several wars that would culminate with World War II.

New Order Movement[edit]

During 1940, Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe proclaimed the Shintaisei (New National Structure), making Japan into a "National Defense State". Under the National Mobilization Law, the government was given absolute power over the nation's assets. All political parties were ordered to dissolve into the Imperial Rule Assistance Association, forming a one-party state based on totalitarian values. Such measures as the National Service Draft Ordinance and the National Spiritual Mobilization Movement were intended to mobilize Japanese society for a total war against the West.

Associated with government efforts to create a statist society included creation of the Tonarigumi (residents' committees), and emphasis on the Kokutai no Hongi ("Japan's Fundamentals of National Policy"), presenting a view of Japan's history, and its mission to unite the East and West under the Hakkō ichiu theory in schools as official texts. The official academic text was another book, Shinmin no Michi (The Subject's Way), the "moral national Bible", presented an effective catechism on nation, religion, cultural, social, and ideological topics.

Axis powers[edit]

Imperial Japan withdrew from the League of Nations in 1933, bringing it closer to Nazi Germany, which also left that year, and Fascist Italy, which was dissatisfied with the League. During the 1930s Japan drifted further away from Western Europe and the United States. During this period, American, British, and French films were increasingly censored, and in 1937 Japan froze all American assets throughout its empire.[14]

In 1940, the three countries formed the Axis powers, and became more closely linked. Japan imported German propaganda films such as Ohm Krüger (1941), advertising them as narratives showing the suffering caused by Western imperialism.

End of military statism[edit]

Japanese statism was discredited and destroyed by the failure of Japan's military in World War II. After the surrender of Japan, Japan was put under Allied occupation. Some of its former military leaders were tried for war crimes before the Tokyo tribunal, the government educational system was revised, and the tenets of liberal democracy were written into the post-war Constitution of Japan as one of its key themes.

The collapse of statist ideologies in 1945–46 was paralleled by a formalisation of relations between the Shinto religion and the Japanese state, including disestablishment: termination of Shinto's status as a state religion. In August 1945, the term State Shinto (Kokka Shintō) was invented to refer to some aspects of statism. On 1 January 1946, Emperor Shōwa issued an imperial rescript, sometimes referred as the Ningen-sengen ("Humanity Declaration") in which he quoted the Five Charter Oath (Gokajō no Goseimon) of his grandfather, Emperor Meiji and renounced officially "the false conception that the Emperor is a divinity". However, the wording of the Declaration – in the court language of the Imperial family, an archaic Japanese dialect known as Kyūteigo – and content of this statement have been the subject of much debate. For instance, the renunciation did not include the word usually used to impute the Emperor's divinity: arahitogami ("living god"). It instead used the unusual word akitsumikami, which was officially translated as "divinity", but more literally meant "manifestation/incarnation of a kami ("god/spirit")". Hence, commentators such as John W. Dower and Herbert P. Bix have argued, Hirohito did not specifically deny being a "living god" (arahitogami).

See also[edit]

- Imperial Way Faction

- List of Japanese political figures in early Shōwa period

- Nazism

- Italian Fascism

- List of Japanese institutions (1930–45)

- Propaganda in Japan during World War II

- State Shinto

- Religious nationalism

- Chinilpa (Korean collaborators with Imperial Japan)

- Anti-Korean sentiment in Japan

- Fascism in Asia

- Totalitarianism

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Cyprian Blamires, Paul Jackson, ed. (2006). World Fascism: A-K. ABC-CLIO. p. 353. ISBN 9781576079409.

- ^ Akihiko Takagi, [1][dead link] mentions "Nippon Chiseigaku Sengen ("A manifesto of Japanese Geopolitics") written in 1940 by Saneshige Komaki, a professor of Kyoto Imperial University and one of the representatives of the Kyoto school, [as] an example of the merging of geopolitics into Japanese traditional ultranationalism."

- ^ Torrance, Richard (2009). "The People's Library". In Tansman, Alan (ed.). The culture of Japanese fascism. Durham: Duke University Press. pp. 56, 64–5, 74. ISBN 978-0822344520.

- ^ Herbert Bix, Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, 2001, p.284

- ^ Doak, Kevin (2009). "Fascism Seen and Unseen". In Tansman, Alan (ed.). The culture of Japanese fascism. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0822344520.

Careful attention to the history of the Special Higher Police, and particularly to their use by Prime Minister Tōjō Hideki against his enemies even further to his political right, reveals that extreme rightists, fascists, and practically anyone deemed to pose a threat to the Meiji constitutional order were at risk.

- ^ a b Anthony Rhodes, Propaganda: The art of persuasion: World War II, p246 1976, Chelsea House Publishers, New York

- ^ Andrew Gordon, A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa to the Present, p195-6, ISBN 0-19-511060-9, OCLC 49704795

- ^ Andrew Gordon, A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa to the Present, p196, ISBN 0-19-511060-9, OCLC 49704795

- ^ Bix, Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, page 164

- ^ Reynolds, Japan in the Fascist Era, page 76

- ^ John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War p223 ISBN 0-394-50030-X

- ^ W. G. Beasley, The Rise of Modern Japan, p 187 ISBN 0-312-04077-6

- ^ John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War p27 ISBN 0-394-50030-X

- ^ Baskett, Michael (2009). "All Beautiful Fascists?: Axis Film Culture in Imperial Japan". In Tansman, Alan (ed.). The Culture of Japanese Fascism. Durham: Duke University Press. pp. 217–8. ISBN 978-0822344520.

Bibliography[edit]

- Beasley, William G. (1991). Japanese Imperialism 1894-1945. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-822168-1.

- Bix, Herbert P. (2001). Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan. Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-093130-2.

- Dower, John W. (1986). War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War. Pantheon. ISBN 0-394-50030-X.

- Duus, Peter (2001). The Cambridge History of Japan. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-23915-7.

- Gordon, Andrew (2003). A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-511060-9.

- Gow, Ian (2004). Military Intervention in Pre-War Japanese Politics: Admiral Kato Kanji and the Washington System'. RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 0-7007-1315-8.

- Hook, Glenn D (2007). Militarization and Demilitarization in Contemporary Japan. Taylor & Francis. ASIN B000OI0VTI.

- Maki, John M (2007). Japanese Militarism, Past and Present. Thompson Press. ISBN 978-1-4067-2272-7.

- Reynolds, E Bruce (2004). Japan in the Fascist Era. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1-4039-6338-X.

- Sims, Richard (2001). Japanese Political History Since the Meiji Renovation 1868-2000. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-23915-7.

- Stockwin, JAA (1990). Governing Japan: Divided Politics in a Major Economy. Vintage. ISBN 0-679-72802-3.

- Storry, Richard. "Fascism in Japan: The Army Mutiny of February 1936" History Today (Nov 1956) 6#11 pp 717–726.

- Sunoo, Harold Hwakon (1975). Japanese Militarism, Past and Present. Burnham Inc Pub. ISBN 0-88229-217-X.

- Wolferen, Karen J (1990). The Enigma of Japanese Power;People and Politics in a Stateless Nation. Vintage. ISBN 0-679-72802-3.

- Brij, Tankha (2006). Kita Ikki And the Making of Modern Japan: A Vision of Empire. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 1-901903-99-0.

- Wilson, George M (1969). Radical Nationalist in Japan: Kita Ikki 1883-1937. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-74590-6.

- Was Kita Ikki a Socialist?, Nik Howard, 2004.

- Baskett, Michael (2009). "All Beautiful Fascists?: Axis Film Culture in Imperial Japan" in The Culture of Japanese Fascism, ed. Alan Tansman. Durham: Duke University Press. pp. 212–234. ISBN 0822344521

- Bix, Herbert. (1982) "Rethinking Emperor-System Fascism" Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars. v. 14, pp. 20–32.

- Dore, Ronald, and Tsutomu Ōuchi. (1971) "Rural Origins of Japanese Fascism. " in Dilemmas of Growth in Prewar Japan, ed. James Morley. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 181–210. ISBN 0-691-03074-X

- Duus, Peter and Daniel I. Okimoto. (1979) "Fascism and the History of Prewar Japan: the Failure of a Concept, " Journal of Asian Studies, vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 65–76.

- Fletcher, William Miles. (1982) The Search for a New Order: Intellectuals and Fascism in Prewar Japan. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-1514-4

- Maruyama, Masao. (1963) "The Ideology and Dynamics of Japanese Fascism" in Thought and Behavior in Modern Japanese Politics, ed. Ivan Morris. Oxford. pp. 25–83.

- McGormack, Gavan. (1982) "Nineteen-Thirties Japan: Fascism?" Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars v. 14 pp. 2–19.

- Morris, Ivan. ed. (1963) Japan 1931-1945: Militarism, Fascism, Japanism? Boston: Heath.

- Tanin, O. and E. Yohan. (1973) Militarism and Fascism in Japan. Westport, Conn. : Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-8371-5478-2

External links[edit]

- About Japanese Nationalist groups, Kempeitai, Kwantung Army, Group 371 and other relationed topics

- Info about Japanese secret societies Archived 2012-07-17 at the Wayback Machine

- Article on Alan Tansman's forthcoming book, The Aesthetics of Japanese Fascism.[dead link]

- The Fascist Next Door? Nishitani Keiji and the Chuokoron Discussions in Perspective, Discussion Paper by Xiaofei Tu in the electronic journal of contemporary japanese studies, 27 July 2006.

- The 'Uyoku Rōnin Dō', Assessing the Lifestyles and Values of Japan's Contemporary Right Wing Radical Activists, Discussion Paper by Daiki Shibuichi in the electronic journal of contemporary japanese studies, 28 November 2007.

天皇制ファシズム

| 政治シリーズ記事からの派生 |

| ファシズム |

|---|

| Portal:政治学 |

皇室制度における結束主義(こうしつせいどにおけるけっそくしゅぎ)とは、第二次世界大戦終結までの日本の皇室制度による体制や社会が結束主義の一種であったとする視点による用語。1946年に丸山眞男が著書『超国家主義の論理と心理 他八篇』所収「超国家主義の論理と心理」で使用した[1]。1970年代まで一定の地位を占めたが、ポストモダンの多面的な研究が進んだ1980年代以降には反論意見が相次いだ[2]。

概要[編集]

「天皇制ファシズム」または「日本ファシズム」との表現が使用されたのは、主に第二次世界大戦終結後からである。日本ファシズム連盟は小規模な政党であった。新体制運動はヨーロッパのファシズム運動の影響を受け、大政翼賛会につながったが、天皇の輔弼を掲げたもので一党独裁を掲げたものではなかった。五来欣造は、1931年にイタリア、フランス、ドイツ、イギリス、ロシアを回り、1932年に「ファッショか共産主義か」という講演を行っており、1933年に講演録が発行された[3]。この講演の中で、ソ連の共産主義即ち無産階級による利己主義の失敗とイギリス、イタリア、ドイツにおけるファッショ(結束)の台頭を引いて、「ファッショとは階級的の利己主義に対する弾圧であって、国民経済の統一と、階級の調和を行うものであるとこう言うことができる」「ヨーロッパは無産階級の利己主義、即ち世界大戦以来、労働者の勢力、無産階級の勢力が余りに強くなって、資本を食い荒らして遂に行き詰まった。これに対して反動的に起こったものは今日のファッショ運動である。そういう意味においてファッショは、階級的利己主義に対して、国民本位の政治、即ち全体主義を主張している次第である」「階級の利益だけを計れば、国の窮乏となって、労働階級それ自身も、又遂に衣食の欠乏を来すという事実を、我等はかのロシアにおいて現実に見るのである」と述べている[3]。

1932年の五・一五事件後、昭和天皇は犬養毅首相の後継推薦を行う元老西園寺公望に対し、「ファッショに近き者は絶対に不可なり」と要望を述べた[4]。

1932年10月、小笠原長生は著書「昭和大暗殺史」で以下のように述べた。

各国には、各国の国情に応じたファシズムが生じなくてはならぬ。即ち、我国においては、日本化したファッショが生まれる(中略)世界的に称されているファッショが、日本の武士道によってでっちあげられたものでなくてはならぬ。— 『昭和大暗殺史』序文、芳山房、1932年10月

1946年、丸山眞男は「超国家主義の論理と心理」[5]で、「ファシズム」を「反革命のもっとも先鋭的な、もっとも戦闘的な形態」と定義して[6] 、イタリアやドイツのファシズムは議会制社会下の大衆運動による「下からのファシズム」であったが、日本のファシズムは軍部や官僚による「上からのファシズム」であったとした[1]。この「日本ファシズム論」は広く影響を与え、特に1940年代から1970年代に類似または関連した見解が多く登場した[7][8][9]。

なお「ファシズム」という用語や概念の定義や範囲には多数の議論があり、学術的な合意は無い。

日本国内のファシズム運動の発展時期区分[編集]

第一の段階は、準備期で、ちょうど世界大戦の終わった頃から満州事変頃に至る時期を「民間における右翼運動の時代」といってよく、年代でいうと大正8年(1919年)・9年(1920年)から昭和6年(1931年)頃まで。

第二段階は、成熟期で、満州事変前後から二・二六事件に至る時期で、前期の運動が軍部勢力の一部と結託して、ファシズム運動の推進力となり、徐々に国政の中心を占めるようになる段階・過程である。また、3月事件、錦旗事件[10]、血盟団事件、五・一五事件、神兵事件、士官学校事件、相沢事件、そして二・二六事件等に至るファッショのテロリズムが次々と勃発した時期である。年代的にいうと昭和6年(1931年)頃から昭和11年(1936年)に至る。

第三期は、日本ファシズムの完成時期で、官僚・重臣等の半封建的勢力と独占資本やブルジョア政党との間に、軍部が上からの露わな担い手として、不十分ながらも連合支配体制を作り上げた時期である。年代的にいうと昭和11年(1936年)の二・二六事件以後粛軍の時代から昭和20年(1945年)の敗戦までである[11]。

批評[編集]

第二次世界大戦終結までの日本の社会や体制を「天皇制ファシズム」または「日本ファシズム」とみなすかどうかは、肯定論と否定論が存在する。

肯定論[編集]

- 三輪泰史は著書「日本ファシズムと労働運動」で、以下の見解を述べた。1935年頃を画期として、「警察精神」の作興が進み労使関係・市民生活への警察の介入が深化した。警察は弾圧のみならず、社会的書体率の調整・統合・民衆動員などの機能を果たした。すなわち、イタリアやドイツではファシスト大衆組織が担った役割を担った。日本の「下から」のファシズム運動は、軍部・官僚などの既成権力への権力依存的特質を有していたとしている [12]

- 教育学者で八戸工業大学教授の松浦勉は著書「日本ファシズムの戦争教育体制と融和教育」で、以下の見解を述べた。1942年8月に文部省社会教育局は『国民同和への道』を刊行し、はじめて政府の教育方針として同和教育政策の理念・具体的方針を示した。同書は被差別部落の児童・青年を同和教育を通じて「皇国民としての純真な自覚に立たしめ、苦悩に堪え、艱難を忍び、臣道実践に邁進する強健なる心身」に「陶冶・鍛錬」するというものであった。これは旧水平社の「下から」の運動のエネルギーをも利用し、部落の児童・青年を他の児童・青年以上の「皇国民」として「陶冶・鍛錬」することを提示しており、この同和教育の指針を「天皇制ファシズム」教育の極限形態の一つとして把握する学説がある [13]。

- 須崎愼一は著書「日本ファシズムとその時代」で、「様相の違いをもって、日本を、ファシズムでないときめつけてしまうわけにはいかない。同種の国家体制であれ、その国や民族の歴史的伝統や、その環境などによってさまざまなバリエ—ションをもつのは、ごく当然のことだから」との見解を述べた。[14]。

否定論[編集]

- アメリカ人の政治学者、ケビン・M・ドークとグレゴリー・カスザでは、「保守系独裁」というラベルは当てはまるのに、ファシズムはみなされない。ドークによると、明治憲法を守る目的で、政府が標的にした反主流派は左翼だけではなく、右翼とファシストも含んだ[15]。

- コミンテルンおよび神山茂夫の見解では、当時の日本の政治体制は「軍事的・封建的帝国主義」であり、ファシズムとはみなされない。軍事的封建的帝国主義とは、ヨーロッパ列強の帝国主義と帝政ロシアの帝国主義を区別してレーニンが用いた言葉である。日本共産党の綱領も「日本帝国主義」で統一している[16]。

- 古川隆久は著書『昭和戦中期の議会と行政』で以下の見解を述べた。二度にわたる国体明徴声明では「我が国体は天孫降臨の際下し賜へる御神勅に依り昭示せらるる所にして、万世一系の天皇国を統治し給ひ、宝祚の隆は天地と倶に窮なし(第一次)」「政教其他百般の事項総て万邦無比なる我が国体の本義を基とし、その真髄を顕揚するを要す(第二次)」と謳われており、これは自由主義や社会主義のみならずファシズムを含めた外来の政治体制を排除する意図が存在していた(史的にも、これは既成の右派である観念右翼・日本主義者がファシズムを支持する革新右翼を攻撃する際にも用いられた)[17]。

- 姜尚中は、「戦前の日本はファシズムではなく、内部がバラバラの状態。天皇陛下のもとで一つにまとまっているように見えたけれど、かなりセクショナリズム(部局割拠主義)が強かったのではないか。そこがナチスドイツとは大きく違うのかもしれません。」と指摘している[18]。

その他[編集]

- 歴史学者の伊藤隆は、日本ファシズムという概念の流行は、東京裁判の判決によるところが大きいとした。そこでは勝戦国によって、第二次世界大戦がファシズム対民主主義の戦いであるとイデオロギー化され正当化された。この東京裁判の論理が、日本共産党の掲げた「反戦・反ファシズム」とも親近性があったために、戦後学界の主流を成したマルクス主義史学では、戦前の日本の体制を当然の如くファシズムと規定した[19]。

- 政治学者の山口定は、丸山眞男の日本ファシズム論を評価すると同時に、丸山眞男によるファシズムの定義がコミンテルンによる定義と同じであるとの批判にも言及した[1]。

脚注[編集]

- ^ a b c 丸山眞男と歴史の見方(山口定、2000年3月、政策科学7-3)

- ^ 戸ノ下達也、 長木誠司「総力戦と音楽文化 音と声の戦争」p142 青弓社、2008年10月

- ^ a b ファッショか共産主義か 五来欣造 1933年

- ^ 「天皇制と国家: 近代日本の立憲君主制」(増田知子、1999年、309p)

- ^ 初出:『世界』1946年5月号。所収:『現代政治の思想と行動』(上)、未來社、1956年12月。

- ^ この定義、丸山眞男著『[新装版]現代政治の思想と行動』未来社 2006年 所収の同論文(11-28ページ)に書かれていませんでした。孫引の場合出典を変更してください。

- ^ 『万有百科大事典』第11巻、小学館、1973年、494頁

- ^ 天皇制ファシズム論(中村菊男)

- ^ 日本ファシズム研究序說(安部博純)

- ^ 闇に葬られた事件

- ^ 丸山眞男「日本ファシズムの思想と運動」(丸山眞男著 『[新装版] 現代政治の思想と行動』 未来社 2006年 所収 32ページ)

- ^ 三輪泰史『日本ファシズムと労働運動』校倉書房、1988年。

- ^ 松浦勉「日本ファシズムの戦争教育体制と融和教育」日本教育学会『日本教育学会大会発表要旨集録』1991年8月28日参照。

- ^ 「日本ファシズムとその時代」(須崎愼一、大月書店、1998年、382p)

- ^ Doak, Kevin (2009). “Fascism Seen and Unseen”. In Tansman, Alan. The culture of Japanese fascism. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 44. ISBN 0822344521. "Careful attention to the history of the Special Higher Police, and particularly to their use by Prime Minister Tōjō Hideki against his enemies even further to his political right, reveals that extreme rightists, fascists, and practically anyone deemed to pose a threat to the Meiji constitutional order were at risk."

- ^ 日本共産党綱領 - 2004年1月17日 第23回党大会で改定

- ^ 古川隆久『昭和戦中期の議会と行政』(吉川弘文館、2005年)

- ^ “台湾は親日的なのに、韓国が反日的なのはなぜか? 明治初期の「バグ」が一因に 〈AERA〉”. AERA dot. (アエラドット) (20190927T113000+0900). 2019年9月27日閲覧。

- ^ 大塚健洋『大川周明』

参考文献[編集]

- 「天皇制ファシズムと水平運動」『部落問題研究』36号(尾川昌法、1973年2月)

- 「天皇制ファシズムとそのイデオローグたち ― 『国民精神文化研究所』を例にとって」『季刊科学と思想』76号(宮地正人、1990年4月)

- 「西田税と日本ファシズム運動」(堀真清、岩波書店、2007年)

- 「日本ファシズムの形成」(江口圭一、日本評論社、1978年)

- 「日本ファシズムの興亡」(万峰、六興出版、1989年)

- 「日本ファシズムとその時代:天皇制, 軍部, 戦争, 民衆」(須崎慎一、大月書店、1998年)

- 「日本ファシズムと優生思想」(藤野豊、かもがわ出版、1998年)

- 「日本帝国主義と社会運動:日本ファシズム形成の前提」(掛谷宰平、文理閣、2005年)

- 「未完のファシズム―「持たざる国」日本の運命―」(片山杜秀、新潮選書、2012年[1]) - 皇道派を「農本主義ファシスト」、統制派を「生産力ファシスト」と呼び、日本のファシズムは「未完」で終わったとする。

関連項目[編集]

천황제 파시즘

| 정치 시리즈 기사에서 파생 |

| 파시즘 |

|---|

| 포털: 정치학 |

황실제도에 있어서의 결속주의 (이렇게 쓰세이도에 있어서의 굵게 쿠슈기)란, 제2차 세계대전 종결까지의 일본 의 황실 제도 에 의한 체제나 사회가 결속주의 의 일종이었다고 하는 시점에 의한 용어. 1946년에 마루야마 마사오 가 저서 「초국가주의의 논리와 심리 외 팔편」소수 「초국가주의의 논리와 심리」에서 사용했다[1 ] . 1970년대까지 일정한 지위를 차지했지만, 포스트모던의 다면적인 연구가 진행된 1980년대 이후에는 반론의견이 잇따랐다[2 ] .

개요 [ 편집 ]

「천황제 파시즘」 또는 「일본 파시즘」이라는 표현이 사용된 것은 주로 제2차 세계대전 종결 후부터 이다 . 일본 파시즘 연맹은 소규모 정당이었다. 신체제운동 은 유럽의 파시즘운동의 영향을 받아 대정익찬회로 이어 졌지만, 천황 의 가려움 을 내건 것으로 일당 독재를 내건 것은 아니었다. 고래 울조는 1931년에 이탈리아, 프랑스, 독일, 영국, 러시아를 돌고, 1932년에 「패셔인가 공산주의인가」라고 하는 강연을 실시하고 있어, 1933년에 강연록이 발행되었다[3 ] . 이 강연 중, 소련의 공산주의 즉 무산계급에 의한 이기주의의 실패와 영국, 이탈리아, 독일에 있어서의 패셔(결속)의 대두를 끌어, “패셔는 계급적인 이기주의에 대한 탄압이며, 국민경제의 통일과 계급의 조화를 이루는 것이라고 이렇게 말할 수 있다” “유럽은 무산계급의 이기주의, 즉 세계대전 이후 노동자의 세력, 무산계급의 세력이 너무 강해져 자본 이에 반동적으로 일어난 것은 오늘날의 패셔 운동이다.그런 의미에서 패셔는 계급적 이기주의에 대해 국민 본위의 정치, 즉 전체주의를 주장한다. 계급의 이익만을 계측하면, 나라의 빈곤이 되어, 노동계급 그 자체도, 마침내 의식의 결핍을 온다는 사실을, 우리들은의 러시아에서 현실에 본다 그렇다고 말한다 [3]。

1932년의 5·15사건 후, 쇼와 천황 은 개양인 총리의 후계 추천을 실시하는 원로 서원사 공망 에 대해, 「 패셔 에 가까운 사람은 절대로 불가능하다」라고 요망을 말했다 [4] .

1932년 10월, 오가사와라 장생 은 저서 「쇼와 대암살사」에서 다음과 같이 말했다.

각국에는 각국의 국정에 따른 파시즘이 생겨야 한다. 즉, 일본에서는 일본화된 패셔가 태어나는(중략) 세계적으로 칭해지고 있는 패셔가 일본의 무사도에 의해 쫓겨난 것이어야 한다.— '쇼와대암살사' 서문, 요시야마보, 1932년 10월

1946 년 마루야마 마사오 는 "초국가주의 논리와 심리" [5] 에서 "파시즘"을 "반혁명의 가장 날카로운 가장 전투적인 형태"로 정의하고 [6] 이탈리아와 독일의 파시즘은 의회제 사회하의 대중운동에 의한 「아래로부터의 파시즘」이었지만, 일본의 파시즘은 군부나 관료에 의한 「위로부터의 파시즘」이었다고 했다[1 ] . 이 「일본 파시즘론」은 널리 영향을 주고, 특히 1940년대부터 1970년대에 유사 또는 관련한 견해가 많이 등장했다[7][8] [ 9 ] .

또한 "파시즘"이라는 용어나 개념의 정의나 범위에는 다수의 논의가 있으며, 학술적인 합의는 없다.

일본 국내 파시즘 운동의 발전 시기 구분 [ 편집 ]

제1단계는 준비기로, 딱 세계대전이 끝난 무렵부터 만주 사변경에 이르는 시기를 「민간에 있어서의 우익운동의 시대」라고 해도 좋고, 연대라고 하면 다이쇼 8년(1919년 )・9년( 1920년 )부터 쇼와 6년( 1931년 )경까지.

제2단계는 성숙기로 만주사변 전후부터 2·26사건에 이르는 시기로 전기의 운동이 군부세력의 일부와 결탁하여 파시즘운동의 추진력이 되어 서서히 국정의 중심을 차지하게 되는 단계·과정이다. 또한 3월 사건 , 금기 사건 [10] , 혈맹단 사건 , 5·15 사건 , 신병 사건 , 사관학교 사건 , 아이자와 사건 , 그리고 2·26 사건 등에 이르는 패셔의 테러리즘이 잇달아 발발했다 시기이다. 연대적으로 말하면 쇼와 6년(1931년)경부터 쇼와 11년( 1936년 )에 이른다.

제3기는 일본 파시즘의 완성 시기로 관료·중신 등의 반봉건적 세력과 독점자본과 부르주아 정당과의 사이에 군부가 위에서 드러나는 담당자로서 불충분하면서도 연합 지배 체제를 만들어 한 시기이다. 연대적으로 말하면 쇼와 11년(1936년)의 2·26사건 이후 숙군의 시대부터 쇼와 20년(1945년)의 패전까지이다 [ 11 ] .

비평 [ 편집 ]

제2차 세계대전 종결까지 일본의 사회나 체제를 '천황제 파시즘' 또는 '일본 파시즘'으로 간주할지 여부는 긍정론과 부정론이 존재한다.

긍정론 [ 편집 ]

- 삼륜태사 는 저서 '일본 파시즘과 노동운동'에서 다음 견해를 말했다. 1935년경을 획기로 '경찰정신'의 작흥이 진행되어 노사관계·시민생활에 대한 경찰의 개입이 심화 되었다 . 경찰은 탄압뿐만 아니라 사회적 서체율 조정·통합·민중동원 등의 기능을 완수했다. 즉 이탈리아 와 독일 에서는 파시스트 대중조직이 담당한 역할을 맡았다. 일본의 '아래에서' 파시즘 운동은 군부 · 관료 등 기성권력에 대한 권력 의존적 특질을 가지고 있었다고 한다 [12]

- 교육학자로 하치노헤 공업대학 교수인 마츠우라 공부는 저서 ‘일본 파시즘의 전쟁 교육 체제와 융화 교육’에서 다음 견해를 말했다. 1942년 8월 문부성 사회교육국 은 '국민동화로의 길'을 간행하여 처음으로 정부의 교육방침으로서 동화교육 정책의 이념·구체적 방침을 나타냈다. 이 책은 피차별부락 의 아동·청년을 동화교육을 통해 “황국민으로서의 순진한 자각에 세우고, 고뇌에 참아, 난난을 느끼고, 신도 실천에 매진하는 강건한 심신”에 “도야·단련”한다 라는 것이었다. 이것은 구 수평사의 「아래로부터」의 운동의 에너지도 이용해, 부락의 아동・청년을 다른 아동・청년 이상의 「황국민」으로서 「도야・단련」하는 것을 제시하고 있어, 이 동화교육 의 지침을 「천황제 파시즘」교육의 극한 형태의 하나로서 파악하는 학설이 있다 [13] .

- 스자키 료이치 는 저서 「일본 파시즘과 그 시대」로, 「양상의 차이를 가지고, 일본을, 파시즘이 아닌 때 붙여 버릴 수는 없다. 동종의 국가 체제라도, 그 나라나 민족의 역사적 전통이나, 그 환경 등에 따라 다양한 바리에이션을 가지는 것은 극히 당연한 일이기 때문”이라는 견해를 말했다. [14] .

부정론 [ 편집 ]

- 미국인 정치학자 케빈 M. 도크 와 그레고리 카스 자 에서는 보수계 독재라는 라벨은 적용되지만 파시즘은 보이지 않는다. 도크에 따르면 메이지 헌법을 지키기 위해 정부가 표적으로 한 반주류파는 좌익뿐만 아니라 우익과 파시스트도 포함 했다 .

- 코민테른 과 카미야마 시게오 의 견해에서는 당시 일본의 정치체제는 '군사적·봉건적 제국주의 ' 이며 파시즘으로 간주되지 않는다. 군사적 봉건적 제국주의란 유럽 열강의 제국주의와 제정 러시아 의 제국주의를 구별하여 레닌이 사용한 말이다. 일본 공산당 의 강령도 ' 일본 제국주의 '로 통일하고 있다 [16] .

- 후루카와 타카히사 는 저서 「쇼와전 중기의 의회와 행정」에서 이하의 견해를 말했다. 두 번에 걸친 국체 명징 성명 에서는 "우리 국체는 천손 강림 때 내려 가는 가신 군에 의하여 쇼시 세라 루루 곳으로 만세 일계의 천황국을 통치하고 급여 보물의 융은 천지와 우리에게 궁핍(제1차)」 「정교계 타백반의 사항 모두 만방 무비한 우리 국체의 본의를 기초로 하고, 그 진수를 현양하는 것을 필요로 한다(제2차)」라고 주장되고 있어 이것 는 자유주의나 사회주의뿐만 아니라 파시즘을 포함한 외래의 정치 체제를 배제할 의도가 존재하고 있었다(사적으로도, 이것은 기성의 우파인 관념 우익·일본주의자가 파시즘을 지지한다 혁신 우익을 공격할 때도 사용되었다) [17] .

- 강상중은 , 「전전의 일본은 파시즘이 아니고, 내부가 흩어져 있는 상태. 천황 폐하 아래에서 하나에 정리되어 있는 것처럼 보였지만, 상당히 섹셔널리즘(부국 할거주의) 이 강했던 것은 아닐까 그곳이 나치 독일과는 크게 다른 것일지도 모릅니다.”라고 지적하고 있다 [18] .

기타 [ 편집 ]

- 역사학자인 이토 타카시 는 일본 파시즘이라는 개념의 유행은 도쿄 재판 의 판결에 의한 점이 크다고 했다. 거기서는 승전국에 의해, 제2차 세계대전이 파시즘 대민주주의의 싸움이라고 이데올로기화되어 정당화되었다. 이 도쿄 재판의 논리가 일본 공산당 이 내건 '반전·반파시즘'과도 친근성이 있었기 때문에, 전후 학계의 주류를 이룬 마르크스주의 사학에서는, 전전의 일본의 체제를 당연히 파시즘이라고 규정 했다 [19] .

- 정치학자 의 야마구치 정은 , 마루야마 마사오의 일본 파시즘론을 평가하는 것과 동시에, 마루야마 마사오에 의한 파시즘의 정의가 코민테른 에 의한 정의와 같다고의 비판에도 언급했다 [1] .

각주 [ 편집 ]

- ↑ a b c 마루야마 마사오와 역사의 견해 (야마구치 정, 2000년 3월, 정책 과학 7-3)

- ^ 토노시타 타츠야 , 나가키 세이지「총력전과 음악 문화 소리와 목소리의 전쟁」p142 아오미샤 , 2008년 10월

- ↑ a b 패쇼인가 공산주의인가 고래 울조 1933년

- ↑ 「천황제와 국가: 근대 일본의 입헌군주제」( 마스다 토모코 , 1999년, 309p)

- ↑ 첫출:『세계』 1946년 5월호. 소수:『현대 정치의 사상과 행동』(위), 미후샤 , 1956년 12월.

- ^ 이 정의, 마루야마 마사오 저 『[신장판] 현대 정치의 사상과 행동』 미래사 2006년 소수의 동논문(11-28페이지)에 쓰여지지 않았습니다. 손인의 경우 출처를 변경하십시오.

- ↑ 『만유백과대사전』 제11권, 쇼가쿠칸, 1973년, 494쪽

- ↑ 천황제 파시즘론(나카무라 국화남)

- ^ 일본 가족 연구 서문(아베 히로수미)

- ↑ 어둠에 묻힌 사건

- ^ 마루야마 마사오 「일본 파시즘의 사상과 운동」(마루야마 마사오 저 『[신장판] 현대 정치의 사상과 행동』 미래 사

- ^ 삼륜태사『일본 파시즘과 노동운동』교창서방, 1988년.

- ^ 마츠우라 공부 “일본 파시즘의 전쟁 교육 체제와 융화 교육” 일본 교육 학회 “일본 교육 학회 대회 발표 요지 수집” 1991년 8월 28일 참조.

- ↑ 「일본 파시즘과 그 시대」( 스사키 료이치 , 오츠키 서점 , 1998년, 382p)

- ↑ 도악, 케빈 (2009). “보이는 파시즘과 보이지 않는 파시즘”. 탄즈맨에서, 앨런. 일본 파시즘의 문화 . 더럼: 듀크 대학교 출판부. 피. 44. ISBN 0822344521. "특별고등경찰의 역사, 특히 총리 도조 히데키가 자신의 정치적 우익에 대한 그의 적들에 대한 사용에 주의를 기울이면 극우파, 파시스트, 그리고 실질적으로 메이지에 위협이 되는 것으로 간주되는 모든 사람이 헌법 질서가 위험에 처했다."

- ↑ 일본공산당 강령 - 2004년 1월 17일 제23회 당대회에서 개정

- ↑ 후루카와 타카히사「쇼와전 중기의 의회와 행정」(요시카와 히로후미칸, 2005년)

- ^ “ 대만 은 친일적인데, 한국이 반일적인 것은 왜인가? 메이지 초기의 “버그” 가 일인 에 〈AERA〉 브라우징.

- ↑ 오츠카 켄요 「오카와 슈메이」

참고 문헌 [ 편집 ]

- 「천황제 파시즘과 수평 운동」 「부락 문제 연구」36호( 오가와 창법 , 1973년 2월)

- 「천황제 파시즘과 그 이데올로그들 ― 『국민정신문화연구소』를 예로 한다」 『계간과학과 사상』 76호(미야지 마사토, 1990년 4 월 )

- 「니시다세와 일본 파시즘 운동」( 호리 마키요시 , 이와나미 서점, 2007년)

- 「일본 파시즘의 형성」( 에구치 케이이치 , 일본 평론사, 1978년)

- 「일본 파시즘의 흥망」( 만봉 , 육흥 출판, 1989년)

- 「일본 파시즘과 그 시대:천황제, 군부, 전쟁, 민중」( 스자키 신이치 , 오츠키 서점, 1998년)

- 「일본 파시즘과 우생 사상」(후 지노 유타카 , 카모가와 출판, 1998년)

- 「일본 제국주의와 사회 운동:일본 파시즘 형성의 전제」( 가케야 아야히라 , 문리각, 2005년)

- 「미완의 파시즘―「 갖고 싶은 나라」일본의 운명―」(카타야마 모리히데 , 신 시오 선서 , 2012 년 [ 1 ] ) 불러 일본의 파시즘은 「미완」으로 끝났다고 한다.