Are There White People in the Bible?

January 3, 2021

By Tim Gee

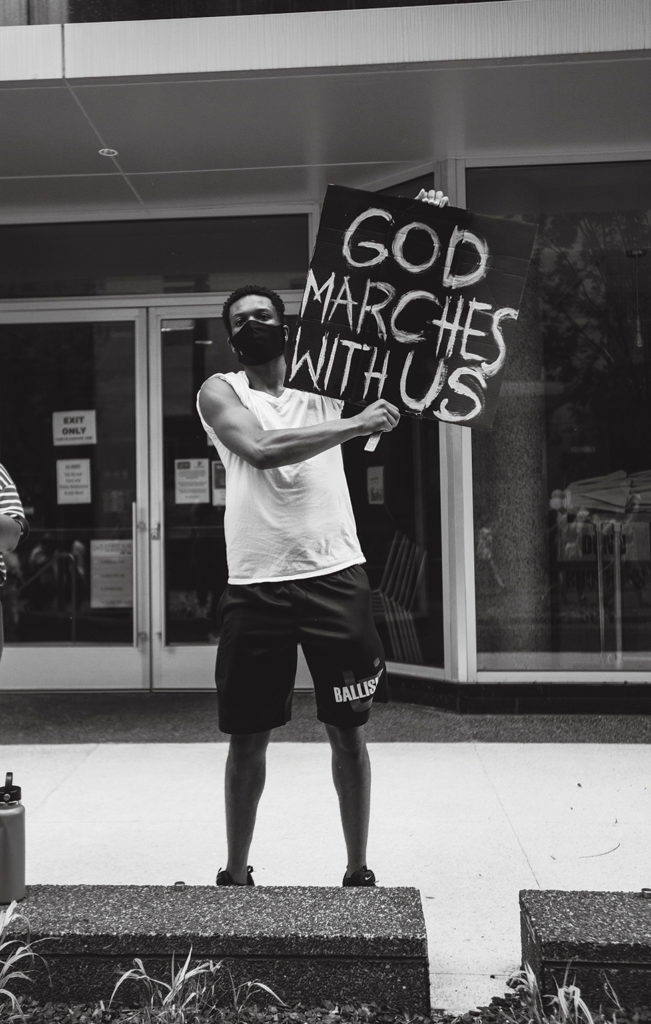

Left: Nicodemus and Jesus on a Rooftop (1899), oil on canvas, by Henry Ossawa Tanner. Joseph E. Temple Fund, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, Pa. Public domain. Below: Black Lives Matter protest, Nashville, Tenn., June 4, 2020.

The Swiss anti-fascist theologian Karl Barth is well-known for advising people to read Scripture with the Bible in one hand and the newspaper in the other. If he lived today, would he have advised the same when using our smartphones and scrolling through social media feeds?

That’s what I was doing when I came across one of the popular images of 2020: a White woman at a Black Lives Matter demonstration with a placard that read “There are no White people in the Bible (take all of the time you need with this).” That seemed like something worth taking time over.

White Christianity has often depicted characters in biblical scenes as pale-skinned. Given the people’s origins and location, this is unlikely. Christianity in its origins was a movement consisting principally of colonized people who suffered under military occupation in the Middle East and Africa. The opening lines of Matthew even give us a family tree that shows Joseph, a many-times grandchild of Abraham and Sarah, as the descendent of migrants from what is now Iraq.

The early part of the Acts of the Apostles gives us a taste of the diversity of the early Christian movement: it mentions people from the places now called Iran, Iraq, Turkey, Egypt, Libya, Syria, and the occupied Palestinian territories. The first non-Jewish person to join the movement was a eunuch from Ethiopia who worked in what is now Sudan. (As I list these countries, I can’t ignore that many of them were on Donald Trump’s 2017 travel ban.)

Does that mean though that there are no White people in the Bible? Race isn’t only about color; it is a social system about power. In this respect, the Bible shows systems of inequality that are all too familiar. Although it’s true that the Roman army was much more ethnically diverse than White history often chooses to remember, it’s likely that at least some of the Roman occupiers would have been—what we now call—of European descent.

I think there is one person in the Jesus movement who we can be pretty sure was White by something close to our current definition of the term. His name was Cornelius, a Roman soldier of the “Italian regiment,” who to everyone’s surprise asked to join the movement: the second Gentile to do so. No one seemed to have worried when the first non-Jew joined (the Ethiopian eunuch working for the Kingdom of Kush). That is perhaps because that kingdom did not oppress the Hebrew people, and was a historic opponent of Roman imperialism. In contrast, the prospect of an oppressor joining leads to an almighty row, which in different forms continues through the Book of Acts, as Paul takes the movement through the Greco-Roman world. One might imagine the debate in today’s context if a lot of White police officers started joining Black Lives Matter groups.

The controversy in Acts is finally resolved when Peter and James agree that the Greco-Roman gentiles Paul is converting do have a place under certain conditions; afterall, the Spirit had been poured out on all people at Pentecost. But White readers would do well to read this passage with humility. Christianity’s beginnings are in what we’d now call a Black, Indigenous, and People of Color-led movement to which people of European descent were only a later addition. As some must have feared from the start, White Christianity has often acted much more like the Roman Empire than it has like the Kingdom of Heaven. In 2018, the U.S. attorney general even quoted Paul’s letter to the Romans to justify separating migrant children from their families.

Reading about Paul side by side with a book like Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility or Layla Saad’s Me and White Supremacy is enlightening. In stark contrast to Peter, James, and John in Jerusalem, Paul is a citizen of the Roman Empire, a form of unearned power and privilege that saves his life several times; provides him better treatment in custody; and, on one occasion, even prompts an apology from the authorities. Reading his letters—to the Galatians for example—we may well interpret some of his less-sensitive comments as flowing from the fragility and injured pride of the privileged.

© Andrew Winkler/Unsplash

As someone who tries to navigate the challenges of simultaneously living in and trying to transform a system that is imbued with injustice, I recognize similar challenges faced by Paul. In his final letter, he admits he is a “slave to sin.” This prompts uncomfortable questions for me. It is likely that despite my efforts, as a White person, I too perpetuate the structural sins I benefit from: are there times when I too am insensitive or unaware of negative consequences of my actions? Even in this, I find some comfort: incomplete as Paul’s perspective inevitably was, he did what he could. Even in his imperfection, God had a purpose for him.

Objectively, it’s true that there are no White people in the Bible. As Katharine Gerbner explained in “Slavery in the Quaker World” in the September 2019 issue of Friends Journal, the system of categorizing people according to race is only a few hundred years old. But Gerbner also explained that the system of White supremacy, as we know it today, was rooted in and aided and abetted by White Christianity. To uproot White supremacy from our faith, we need to go deeper to its origins, and see what our foundational texts say to us.

When we take the Scriptures as a whole from beginning to end, we see that God takes the side of the outsider and the oppressed. As a pioneer of Black liberation theology, James H. Cone explains: “God did not become a universal human being but an oppressed Jew, thereby disclosing to us that both human nature and divine nature are inseparable from oppression and liberation.”

Cone didn’t live to see the global reaction to the killing of George Floyd, but his words have gained a new life among Christians concerned about racism:

Until we can see the cross and the lynching tree together, until we can identify Christ with a “re-crucified” black body hanging from a lynching tree, there can be no genuine understanding of Christian identity in America, and no deliverance from the brutal legacy of slavery and white supremacy.

Black Lives Matter

God

Roman Empire

White Christianity

Features

Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

Tim Gee

Tim Gee is a member of Britain Yearly Meeting. He is the author of Why I Am a Pacifist. His next book, Open for Liberation: An Activist Reads the Bible, is due later this ye