Animism

Animism (from Latin: anima meaning 'breath, spirit, life')[1][2] is the belief that objects, places, and creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence.[3][4][5][6] Animism perceives all things—animals, plants, rocks, rivers, weather systems, human handiwork, and in some cases words—as animated and alive. Animism is used in anthropology of religion as a term for the belief system of many Indigenous peoples,[7] in contrast to the relatively more recent development of organized religions.[8] Animism focuses on the metaphysical universe, with a specific focus on the concept of the immaterial soul.[9]

Although each culture has its own mythologies and rituals, animism is said to describe the most common, foundational thread of indigenous peoples' "spiritual" or "supernatural" perspectives. The animistic perspective is so widely held and inherent to most indigenous peoples that they often do not even have a word in their languages that corresponds to "animism" (or even "religion").[10] The term "animism" is an anthropological construct.

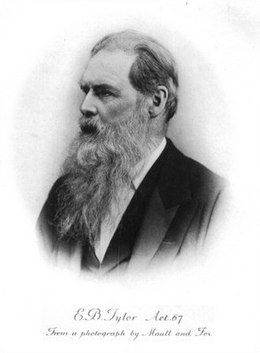

Largely due to such ethnolinguistic and cultural discrepancies, opinions differ on whether animism refers to an ancestral mode of experience common to indigenous peoples around the world or to a full-fledged religion in its own right. The currently accepted definition of animism was only developed in the late 19th century (1871) by Edward Tylor. It is "one of anthropology's earliest concepts, if not the first."[11]

Animism encompasses beliefs that all material phenomena have agency, that there exists no categorical distinction between the spiritual and physical world, and that soul, spirit, or sentience exists not only in humans but also in other animals, plants, rocks, geographic features (such as mountains and rivers), and other entities of the natural environment. Examples include water sprites, vegetation deities, and tree spirits, among others. Animism may further attribute a life force to abstract concepts such as words, true names, or metaphors in mythology. Some members of the non-tribal world also consider themselves animists, such as author Daniel Quinn, sculptor Lawson Oyekan, and many contemporary Pagans.[12]

Etymology[edit]

English anthropologist, Sir Edward Tylor initially wanted to describe the phenomenon as spiritualism, but he realized that it would cause confusion with the modern religion of spiritualism, which was then prevalent across Western nations.[13] He adopted the term animism from the writings of German scientist Georg Ernst Stahl,[14] who had developed the term animismus in 1708 as a biological theory that souls formed the vital principle, and that the normal phenomena of life and the abnormal phenomena of disease could be traced to spiritual causes.[15]

The origin of the word comes from the Latin word anima, which means life or soul.[16]

The first known usage in English appeared in 1819.[17]

"Old animism" definitions[edit]

Earlier anthropological perspectives, which have since been termed the old animism, were concerned with knowledge on what is alive and what factors make something alive.[18] The old animism assumed that animists were individuals who were unable to understand the difference between persons and things.[19] Critics of the old animism have accused it of preserving "colonialist and dualistic worldviews and rhetoric."[20]

Edward Tylor's definition[edit]

The idea of animism was developed by anthropologist Sir Edward Tylor through his 1871 book Primitive Culture,[1] in which he defined it as "the general doctrine of souls and other spiritual beings in general." According to Tylor, animism often includes "an idea of pervading life and will in nature;"[21] a belief that natural objects other than humans have souls. This formulation was little different from that proposed by Auguste Comte as "fetishism",[22] but the terms now have distinct meanings.

For Tylor, animism represented the earliest form of religion, being situated within an evolutionary framework of religion that has developed in stages and which will ultimately lead to humanity rejecting religion altogether in favor of scientific rationality.[23] Thus, for Tylor, animism was fundamentally seen as a mistake, a basic error from which all religions grew.[23] He did not believe that animism was inherently illogical, but he suggested that it arose from early humans' dreams and visions and thus was a rational system. However, it was based on erroneous, unscientific observations about the nature of reality.[24] Stringer notes that his reading of Primitive Culture led him to believe that Tylor was far more sympathetic in regard to "primitive" populations than many of his contemporaries and that Tylor expressed no belief that there was any difference between the intellectual capabilities of "savage" people and Westerners.[4]

The idea that there had once been "one universal form of primitive religion" (whether labelled animism, totemism, or shamanism) has been dismissed as "unsophisticated" and "erroneous" by archaeologist Timothy Insoll, who stated that "it removes complexity, a precondition of religion now, in all its variants".[25]

Social evolutionist conceptions[edit]

Tylor's definition of animism was part of a growing international debate on the nature of "primitive society" by lawyers, theologians, and philologists. The debate defined the field of research of a new science: anthropology. By the end of the 19th century, an orthodoxy on "primitive society" had emerged, but few anthropologists still would accept that definition. The "19th-century armchair anthropologists" argued, that "primitive society" (an evolutionary category) was ordered by kinship and divided into exogamous descent groups related by a series of marriage exchanges. Their religion was animism, the belief that natural species and objects had souls.

With the development of private property, the descent groups were displaced by the emergence of the territorial state. These rituals and beliefs eventually evolved over time into the vast array of "developed" religions. According to Tylor, as society became more scientifically advanced, fewer members of that society would believe in animism. However, any remnant ideologies of souls or spirits, to Tylor, represented "survivals" of the original animism of early humanity.[26]

—Graham Harvey, 2005.[27]

Confounding animism with totemism[edit]

In 1869 (three years after Tylor proposed his definition of animism), Edinburgh lawyer John Ferguson McLennan, argued that the animistic thinking evident in fetishism gave rise to a religion he named totemism. Primitive people believed, he argued, that they were descended from the same species as their totemic animal.[22] Subsequent debate by the "armchair anthropologists" (including J. J. Bachofen, Émile Durkheim, and Sigmund Freud) remained focused on totemism rather than animism, with few directly challenging Tylor's definition. Anthropologists "have commonly avoided the issue of animism and even the term itself, rather than revisit this prevalent notion in light of their new and rich ethnographies."[28]

According to anthropologist Tim Ingold, animism shares similarities with totemism but differs in its focus on individual spirit beings which help to perpetuate life, whereas totemism more typically holds that there is a primary source, such as the land itself or the ancestors, who provide the basis to life. Certain indigenous religious groups such as the Australian Aboriginals are more typically totemic in their worldview, whereas others like the Inuit are more typically animistic.[29]

From his studies into child development, Jean Piaget suggested that children were born with an innate animist worldview in which they anthropomorphized inanimate objects and that it was only later that they grew out of this belief.[30] Conversely, from her ethnographic research, Margaret Mead argued the opposite, believing that children were not born with an animist worldview but that they became acculturated to such beliefs as they were educated by their society.[30]

Stewart Guthrie saw animism—or "attribution" as he preferred it—as an evolutionary strategy to aid survival. He argued that both humans and other animal species view inanimate objects as potentially alive as a means of being constantly on guard against potential threats.[31] His suggested explanation, however, did not deal with the question of why such a belief became central to the religion.[32] In 2000, Guthrie suggested that the "most widespread" concept of animism was that it was the "attribution of spirits to natural phenomena such as stones and trees."[33]

"New animism" non-archaic definitions[edit]

Many anthropologists ceased using the term animism, deeming it to be too close to early anthropological theory and religious polemic.[20] However, the term had also been claimed by religious groups—namely, Indigenous communities and nature worshippers—who felt that it aptly described their own beliefs, and who in some cases actively identified as "animists".[34] It was thus readopted by various scholars, who began using the term in a different way,[20] placing the focus on knowing how to behave toward other beings, some of whom are not human.[18] As religious studies scholar Graham Harvey stated, while the "old animist" definition had been problematic, the term animism was nevertheless "of considerable value as a critical, academic term for a style of religious and cultural relating to the world."[35]

Hallowell and the Ojibwe[edit]

The new animism emerged largely from the publications of anthropologist Irving Hallowell, produced on the basis of his ethnographic research among the Ojibwe communities of Canada in the mid-20th century.[36] For the Ojibwe encountered by Hallowell, personhood did not require human-likeness, but rather humans were perceived as being like other persons, who for instance included rock persons and bear persons.[37] For the Ojibwe, these persons were each wilful beings, who gained meaning and power through their interactions with others; through respectfully interacting with other persons, they themselves learned to "act as a person".[37]

Hallowell's approach to the understanding of Ojibwe personhood differed strongly from prior anthropological concepts of animism.[38] He emphasized the need to challenge the modernist, Western perspectives of what a person is, by entering into a dialogue with different worldwide views.[37] Hallowell's approach influenced the work of anthropologist Nurit Bird-David, who produced a scholarly article reassessing the idea of animism in 1999.[39] Seven comments from other academics were provided in the journal, debating Bird-David's ideas.[40]

Postmodern anthropology[edit]

More recently, postmodern anthropologists are increasingly engaging with the concept of animism. Modernism is characterized by a Cartesian subject-object dualism that divides the subjective from the objective, and culture from nature. In the modernist view, animism is the inverse of scientism, and hence, is deemed inherently invalid by some anthropologists. Drawing on the work of Bruno Latour, some anthropologists question modernist assumptions and theorize that all societies continue to "animate" the world around them. In contrast to Tylor's reasoning, however, this "animism" is considered to be more than just a remnant of primitive thought. More specifically, the "animism" of modernity is characterized by humanity's "professional subcultures", as in the ability to treat the world as a detached entity within a delimited sphere of activity.

Human beings continue to create personal relationships with elements of the aforementioned objective world, such as pets, cars, or teddy bears, which are recognized as subjects. As such, these entities are "approached as communicative subjects rather than the inert objects perceived by modernists."[41] These approaches aim to avoid the modernist assumption that the environment consists of a physical world distinct from the world of humans, as well as the modernist conception of the person being composed dualistically of a body and a soul.[28]

Nurit Bird-David argues that:[28]

She explains that animism is a "relational epistemology" rather than a failure of primitive reasoning. That is, self-identity among animists is based on their relationships with others, rather than any distinctive features of the "self". Instead of focusing on the essentialized, modernist self (the "individual"), persons are viewed as bundles of social relationships ("dividuals"), some of which include "superpersons" (i.e. non-humans).

Stewart Guthrie expressed criticism of Bird-David's attitude towards animism, believing that it promulgated the view that "the world is in large measure whatever our local imagination makes it". This, he felt, would result in anthropology abandoning "the scientific project".[42]

Like Bird-David, Tim Ingold argues that animists do not see themselves as separate from their environment:[43]

Rane Willerslev extends the argument by noting that animists reject this Cartesian dualism and that the animist self identifies with the world, "feeling at once within and apart from it so that the two glide ceaselessly in and out of each other in a sealed circuit".[44] The animist hunter is thus aware of himself as a human hunter, but, through mimicry, is able to assume the viewpoint, senses, and sensibilities of his prey, to be one with it.[45] Shamanism, in this view, is an everyday attempt to influence spirits of ancestors and animals, by mirroring their behaviors, as the hunter does its prey.

Ethical and ecological understanding[edit]

This section's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (December 2022) |

Cultural ecologist and philosopher David Abram promotes an ethical and ecological understanding of animism, grounded in the phenomenology of sensory experience. In his books The Spell of the Sensuous, and Becoming Animal, Abram suggests that material things are never entirely passive in our direct perceptual experience, holding rather that perceived things actively "solicit our attention" or "call our focus", coaxing the perceiving body into an ongoing participation with those things.[46][47]

In the absence of intervening technologies, he suggests, sensory experience is inherently animistic in that it discloses a material field that is animate and self-organizing from the beginning. Drawing upon contemporary cognitive and natural science, as well as upon the perspectival worldviews of diverse indigenous oral cultures, Abram proposes a richly pluralist and story-based cosmology in which matter is alive. He suggests that such a relational ontology is in close accord with humanity's spontaneous perceptual experience by drawing attention to the senses, and to the primacy of the sensuous terrain, enjoining a more respectful and ethical relation to the more-than-human community of animals, plants, soils, mountains, waters, and weather-patterns that materially sustains humanity.[46][47]

In contrast to a long-standing tendency in the Western social sciences, which commonly provide rational explanations of animistic experience, Abram develops an animistic account of reason itself. He holds that civilized reason is sustained only by intensely animistic participation between human beings and their own written signs. For instance, as soon as one reads letters on a page or screen, they can "see what they say"—the letters speak as much as nature spoke to pre-literate peoples. For Abram, reading can usefully be understood as an intensely concentrated form of animism, one that effectively eclipses all of the other, older, more spontaneous forms of animistic participation in which humans were once engaged.

Relation to the concept of 'I-thou'[edit]

Religious studies scholar Graham Harvey defined animism as the belief "that the world is full of persons, only some of whom are human, and that life is always lived in relationship with others."[18] He added that it is therefore "concerned with learning how to be a good person in respectful relationships with other persons."[18]

In his Handbook of Contemporary Animism (2013), Harvey identifies the animist perspective in line with Martin Buber's "I-thou" as opposed to "I-it". In such, Harvey says, the animist takes an I-thou approach to relating to the world, whereby objects and animals are treated as a "thou", rather than as an "it".[49]

Religion[edit]

There is ongoing disagreement (and no general consensus) as to whether animism is merely a singular, broadly encompassing religious belief[50] or a worldview in and of itself, comprising many diverse mythologies found worldwide in many diverse cultures.[51][52] This also raises a controversy regarding the ethical claims animism may or may not make: whether animism ignores questions of ethics altogether;[53] or, by endowing various non-human elements of nature with spirituality or personhood,[54] in fact promotes a complex ecological ethics.[55]

Concepts[edit]

Distinction from pantheism[edit]

Animism is not the same as pantheism, although the two are sometimes confused. Moreover, some religions are both pantheistic and animistic. One of the main differences is that while animists believe everything to be spiritual in nature, they do not necessarily see the spiritual nature of everything in existence as being united (monism), the way pantheists do. As a result, animism puts more emphasis on the uniqueness of each individual soul. In pantheism, everything shares the same spiritual essence, rather than having distinct spirits or souls.[56][57]

Fetishism / totemism[edit]

In many animistic world views, the human being is often regarded as on a roughly equal footing with other animals, plants, and natural forces.[58]

African indigenous religions[edit]

Traditional African religions: most religious traditions of Sub-Saharan Africa, which are basically a complex form of animism with polytheistic and shamanistic elements and ancestor worship.[59]

In North Africa, the traditional Berber religion includes the traditional polytheistic, animist, and in some rare cases, shamanistic, religions of the Berber people.

Asian origin religions[edit]

Indian-origin religions[edit]

In the Indian-origin religions, namely Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism, the animistic aspects of nature worship and ecological conservation are part of the core belief system.

Matsya Purana, a Hindu text, has a Sanskrit language shloka (hymn), which explains the importance of reverence of ecology. It states, "A pond equals ten wells, a reservoir equals ten ponds, while a son equals ten reservoirs, and a tree equals ten sons."[60] Indian religions worship trees such as the Bodhi Tree and numerous superlative banyan trees, conserve the sacred groves of India, revere the rivers as sacred, and worship the mountains and their ecology.

Panchavati are the sacred trees in Indic religions, which are sacred groves containing five type of trees, usually chosen from among the Vata (Ficus benghalensis, Banyan), Ashvattha (Ficus religiosa, Peepal), Bilva (Aegle marmelos, Bengal Quince), Amalaki (Phyllanthus emblica, Indian Gooseberry, Amla), Ashoka (Saraca asoca, Ashok), Udumbara (Ficus racemosa, Cluster Fig, Gular), Nimba (Azadirachta indica, Neem) and Shami (Prosopis spicigera, Indian Mesquite).[61][62]

The banyan is considered holy in several religious traditions of India. The Ficus benghalensis is the national tree of India.[63] Vat Purnima is a Hindu festival related to the banyan tree, and is observed by married women in North India and in the Western Indian states of Maharashtra, Goa, Gujarat.[64] For three days of the month of Jyeshtha in the Hindu calendar (which falls in May–June in the Gregorian calendar) married women observe a fast, tie threads around a banyan tree, and pray for the well-being of their husbands.[65] Thimmamma Marrimanu, sacred to Indian religions, has branches spread over five acres and was listed as the world's largest banyan tree in the Guinness World Records in 1989.[66][67]

In Hinduism, the leaf of the banyan tree is said to be the resting place for the god Krishna. In the Bhagavat Gita, Krishna said, "There is a banyan tree which has its roots upward and its branches down, and the Vedic hymns are its leaves. One who knows this tree is the knower of the Vedas." (Bg 15.1) Here the material world is described as a tree whose roots are upwards and branches are below. We have experience of a tree whose roots are upward: if one stands on the bank of a river or any reservoir of water, he can see that the trees reflected in the water are upside down. The branches go downward and the roots upward. Similarly, this material world is a reflection of the spiritual world. The material world is but a shadow of reality. In the shadow there is no reality or substantiality, but from the shadow we can understand that there is substance and reality.

In Buddhism's Pali canon, the banyan (Pali: nigrodha)[68] is referenced numerous times.[69] Typical metaphors allude to the banyan's epiphytic nature, likening the banyan's supplanting of a host tree as comparable to the way sensual desire (kāma) overcomes humans.[70]

Mun (also known as Munism or Bongthingism) is the traditional polytheistic, animist, shamanistic, and syncretic religion of the Lepcha people.[71][72][73]

Japan and Shinto[edit]

Shinto is the traditional Japanese folk religion and has many animist aspects. The Ryukyuan religion of the Ryukyu islands is distinct from Shinto, but shares similar characteristics.

Kalash people[edit]

Kalash people of Northern Pakistan follow an ancient animistic religion identified with an ancient form of Hinduism.[74]

Korea[edit]

Muism, the native Korean belief, has many animist aspects.[75]

Philippines' native belief[edit]

In the indigenous religious beliefs of the Philippines, pre-colonial religions of Philippines and Philippine mythology, animism is part of their core beliefs as demonstrated by the belief in Anito and Bathala as well as their conservation and veneration of sacred Indigenous Philippine shrines, forests, mountains and sacred grounds.

Anito (lit. '[ancestor] spirit') refers to the various indigenous shamanistic folk religions of the Philippines, led by female or feminized male shamans known as babaylan. It includes belief in a spirit world existing alongside and interacting with the material world, as well as the belief that everything has a spirit, from rocks and trees to animals and humans to natural phenomena.[77][78]

In indigenous Filipino belief, the Bathala is the omnipotent deity which was derived from Sanskrit word for the Hindu supreme deity bhattara,[79][80] as one of the ten avatars of the Hindu god Vishnu.[81][82] The omnipotent Bathala also presides over the spirits of ancestors called Anito.[83][84][85][86] Anitos serve as intermediaries between mortals and the divine, such as Agni (Hindu) who holds the access to divine realms; for this reason they are invoked first and are the first to receive offerings, regardless of the deity the worshipper wants to pray to.[87][88]

Abrahamic religions[edit]

Animism also has influences in Abrahamic religions.

The Old Testament and the Wisdom literature preach the omnipresence of God (Jeremiah 23:24; Proverbs 15:3; 1 Kings 8:27), and God is bodily present in the incarnation of his Son, Jesus Christ. (Gospel of John 1:14, Colossians 2:9).[89] Animism is not peripheral to Christian identity but is its nurturing home ground, its axis mundi. In addition to the conceptual work the term animism performs, it provides insight into the relational character and common personhood of material existence.[3]

With rising awareness of ecological preservation, recently theologians like Mark I. Wallace argue for animistic Christianity with a biocentric approach that understands God being present in all earthly objects, such as animals, trees, and rocks.[90]

Pre-Islamic Arab religion[edit]

Pre-Islamic Arab religion can refer to the traditional polytheistic, animist, and in some rare cases, shamanistic, religions of the peoples of the Arabian Peninsula. The belief in jinn, invisible entities akin to spirits in the Western sense dominant in the Arab religious systems, hardly fit the description of Animism in a strict sense. The jinn are considered to be analogous to the human soul by living lives like that of humans, but they are not exactly like human souls neither are they spirits of the dead.[91]: 49 It is unclear if belief in jinn derived from nomadic or sedentary populations.[91]: 51

Neopagan and New Age movements[edit]

Some Neopagan groups, including Eco-pagans, describe themselves as animists, meaning that they respect the diverse community of living beings and spirits with whom humans share the world and cosmos.[92]

The New Age movement commonly demonstrates animistic traits in asserting the existence of nature spirits.[93]

Shamanism[edit]

A shaman is a person regarded as having access to, and influence in, the world of benevolent and malevolent spirits, who typically enters into a trance state during a ritual, and practices divination and healing.[94]

According to Mircea Eliade, shamanism encompasses the premise that shamans are intermediaries or messengers between the human world and the spirit worlds. Shamans are said to treat ailments and illnesses by mending the soul. Alleviating traumas affecting the soul or spirit restores the physical body of the individual to balance and wholeness. The shaman also enters supernatural realms or dimensions to obtain solutions to problems afflicting the community. Shamans may visit other worlds or dimensions to bring guidance to misguided souls and to ameliorate illnesses of the human soul caused by foreign elements. The shaman operates primarily within the spiritual world, which in turn affects the human world. The restoration of balance results in the elimination of the ailment.[95]

Abram, however, articulates a less supernatural and much more ecological understanding of the shaman's role than that propounded by Eliade. Drawing upon his own field research in Indonesia, Nepal, and the Americas, Abram suggests that in animistic cultures, the shaman functions primarily as an intermediary between the human community and the more-than-human community of active agencies—the local animals, plants, and landforms (mountains, rivers, forests, winds, and weather patterns, all of which are felt to have their own specific sentience). Hence, the shaman's ability to heal individual instances of dis-ease (or imbalance) within the human community is a byproduct of their more continual practice of balancing the reciprocity between the human community and the wider collective of animate beings in which that community is embedded.[96]

Animist life[edit]

Non-human animals[edit]

Animism entails the belief that "all living things have a soul",[This quote needs a citation] and thus, a central concern of animist thought surrounds how animals can be eaten, or otherwise used for humans' subsistence needs.[97] The actions of non-human animals are viewed as "intentional, planned and purposive",[98] and they are understood to be persons, as they are both alive, and communicate with others.[99]

In animist worldviews, non-human animals are understood to participate in kinship systems and ceremonies with humans, as well as having their own kinship systems and ceremonies.[100] Harvey cited an example of an animist understanding of animal behavior that occurred at a powwow held by the Conne River Mi'kmaq in 1996; an eagle flew over the proceedings, circling over the central drum group. The assembled participants called out kitpu ('eagle'), conveying welcome to the bird and expressing pleasure at its beauty, and they later articulated the view that the eagle's actions reflected its approval of the event, and the Mi'kmaq's return to traditional spiritual practices.[101]

In animism, rituals are performed to maintain relationships between humans and spirits. Indigenous peoples often perform these rituals to appease the spirits and request their assistance during activities such as hunting and healing. In the Arctic region, certain rituals are common before the hunt as a means to show respect for the spirits of animals.[102]

Flora[edit]

Some animists also view plant and fungi life as persons and interact with them accordingly.[103] The most common encounter between humans and these plant and fungi persons is with the former's collection of the latter for food, and for animists, this interaction typically has to be carried out respectfully.[104] Harvey cited the example of Māori communities in New Zealand, who often offer karakia invocations to sweet potatoes as they dig up the latter. While doing so, there is an awareness of a kinship relationship between the Māori and the sweet potatoes, with both understood as having arrived in Aotearoa together in the same canoes.[104]

In other instances, animists believe that interaction with plant and fungi persons can result in the communication of things unknown or even otherwise unknowable.[103] Among some modern Pagans, for instance, relationships are cultivated with specific trees, who are understood to bestow knowledge or physical gifts, such as flowers, sap, or wood that can be used as firewood or to fashion into a wand; in return, these Pagans give offerings to the tree itself, which can come in the form of libations of mead or ale, a drop of blood from a finger, or a strand of wool.[105]

The elements[edit]

Various animistic cultures also comprehend stones as persons.[106] Discussing ethnographic work conducted among the Ojibwe, Harvey noted that their society generally conceived of stones as being inanimate, but with two notable exceptions: the stones of the Bell Rocks and those stones which are situated beneath trees struck by lightning, which were understood to have become Thunderers themselves.[107] The Ojibwe conceived of weather as being capable of having personhood, with storms being conceived of as persons known as 'Thunderers' whose sounds conveyed communications and who engaged in seasonal conflict over the lakes and forests, throwing lightning at lake monsters.[107] Wind, similarly, can be conceived as a person in animistic thought.[108]

The importance of place is also a recurring element of animism, with some places being understood to be persons in their own right.[109]

Spirits[edit]

Animism can also entail relationships being established with non-corporeal spirit entities.[110]

Other usage[edit]

Science[edit]

In the early 20th century, William McDougall defended a form of animism in his book Body and Mind: A History and Defence of Animism (1911).

Physicist Nick Herbert has argued for "quantum animism" in which the mind permeates the world at every level:

Werner Krieglstein wrote regarding his quantum Animism:

In Error and Loss: A Licence to Enchantment,[113] Ashley Curtis (2018) has argued that the Cartesian idea of an experiencing subject facing off with an inert physical world is incoherent at its very foundation and that this incoherence is consistent with rather than belied by Darwinism. Human reason (and its rigorous extension in the natural sciences) fits an evolutionary niche just as echolocation does for bats and infrared vision does for pit vipers, and is epistemologically on a par with, rather than superior to, such capabilities. The meaning or aliveness of the "objects" we encounter, rocks, trees, rivers, and other animals, thus depends for its validity not on a detached cognitive judgment, but purely on the quality of our experience. The animist experience, or the wolf's or raven's experience, thus become licensed as equally valid worldviews to the modern western scientific one; they are indeed more valid, since they are not plagued with the incoherence that inevitably arises when "objective existence" is separated from "subjective experience."

Socio-political impact[edit]

Harvey opined that animism's views on personhood represented a radical challenge to the dominant perspectives of modernity, because it accords "intelligence, rationality, consciousness, volition, agency, intentionality, language, and desire" to non-humans.[114] Similarly, it challenges the view of human uniqueness that is prevalent in both Abrahamic religions and Western rationalism.[115]

Art and literature[edit]

Animist beliefs can also be expressed through artwork.[116] For instance, among the Maori communities of New Zealand, there is an acknowledgement that creating art through carving wood or stone entails violence against the wood or stone person and that the persons who are damaged therefore have to be placated and respected during the process; any excess or waste from the creation of the artwork is returned to the land, while the artwork itself is treated with particular respect.[117] Harvey, therefore, argued that the creation of art among the Maori was not about creating an inanimate object for display, but rather a transformation of different persons within a relationship.[118]

Harvey expressed the view that animist worldviews were present in various works of literature, citing such examples as the writings of Alan Garner, Leslie Silko, Barbara Kingsolver, Alice Walker, Daniel Quinn, Linda Hogan, David Abram, Patricia Grace, Chinua Achebe, Ursula Le Guin, Louise Erdrich, and Marge Piercy.[119]

Animist worldviews have also been identified in the animated films of Hayao Miyazaki.[120][121][122][123]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b EB (1878).

- ^ Segal 2004, p. 14.

- ^ a b "Religion and Nature" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ a b Stringer, Martin D. (1999). "Rethinking Animism: Thoughts from the Infancy of our Discipline". Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 5 (4): 541–56. doi:10.2307/2661147. JSTOR 2661147.

- ^ Hornborg, Alf (2006). "Animism, fetishism, and objectivism as strategies for knowing (or not knowing) the world". Ethnos: Journal of Anthropology. 71 (1): 21–32. doi:10.1080/00141840600603129. S2CID 143991508.

- ^ Haught, John F. What Is Religion? An Introduction. Paulist Press. p. 19.

- ^ Hicks, David (2010). Ritual and Belief: Readings in the Anthropology of Religion (3 ed.). Roman Altamira. p. 359.

Tylor's notion of animism—for him the first religion—included the assumption that early Homo sapiens had invested animals and plants with souls ...

- ^ "Animism". Contributed by Helen James; coordinated by Dr. Elliott Shaw with assistance from Ian Favell. ELMAR Project (University of Cumbria). 1998–1999.

- ^ "Interesting facts".

- ^ "Native American Religious and Cultural Freedom: An Introductory Essay". The Pluralism Project. President and Fellows of Harvard College and Diana Eck. 2005. Archived from the original on 23 December 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- ^ Bird-David, Nurit (1999). ""Animism" Revisited: Personhood, Environment, and Relational Epistemology". Current Anthropology. 40 (S1): S67. doi:10.1086/200061.

- ^ Harvey, Graham (2006). Animism: Respecting the Living World. Columbia University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-231-13700-3.

- ^ Harvey 2005, p. 7.

- ^ Harvey 2005, p. 5.

- ^ Harvey 2005, pp. 3–4.

- ^ "Animism - Definition, Meaning & Synonyms". Vocabulary.com. Retrieved 16 January 2023.

- ^ Bird-David, Nurit (1999). ""Animism" Revisited: Personhood, Environment, and Relational Epistemology". Current Anthropology. 40 (S1): S67–S68. doi:10.1086/200061.

- ^ a b c d Harvey 2005, p. xi.

- ^ Harvey 2005, p. xiv.

- ^ a b c Harvey 2005, p. xii.

- ^ Tylor, Edward Burnett (1871). Primitive Culture: Researches into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Art, and Custom. Vol. 1. J. Murray. p. 260.

- ^ a b Kuper, Adam (2005). Reinvention of Primitive Society: Transformations of a Myth (2nd ed.). Florence, KY, US: Routledge. p. 85.

- ^ a b Harvey 2005, p. 6.

- ^ Harvey 2005, p. 8.

- ^ Insoll 2004, p. 29.

- ^ Kuper, Adam (1988). The Invention of Primitive Society: Transformations of an illusion. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 6–7.

- ^ Harvey 2005, p. xiii.

- ^ a b c Bird-David, Nurit (1999). ""Animism" Revisited: Personhood, environment, and relational epistemology". Current Anthropology. 40 (S1): S68. doi:10.1086/200061.

- ^ Ingold, Tim (2000). "Totemism, Animism, and the Depiction of Animals". The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling, and Skill. London: Routledge. pp. 112–113.

- ^ a b Harvey 2005, p. 14.

- ^ Harvey 2005, p. 15.

- ^ Harvey 2005, p. 16.

- ^ Guthrie 2000, p. 106.

- ^ Harvey 2005, pp. xii, 3.

- ^ Harvey 2005, p. xv.

- ^ Harvey 2005, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Harvey 2005, p. 18.

- ^ Harvey 2005, p. 19.

- ^ Harvey 2005, p. 20.

- ^ Harvey 2005, p. 21.

- ^ Hornborg, Alf (2006). "Animism, fetishism, and objectivism as strategies for knowing (or not knowing) the world". Ethnos. 71 (1): 22–4. doi:10.1080/00141840600603129. S2CID 143991508.

- ^ Guthrie 2000, p. 107.

- ^ Ingold, Tim (2000). The Perception of the Environment: Essays in livelihood, dwelling, and skill. New York: Routledge. p. 42.

- ^ Willerslev 2007, p. 24.

- ^ Willerslev 2007, p. 27.

- ^ a b Abram, David. [1996] 1997. The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-than-Human World. Vintage. ISBN 978-0-679-77639-0.

- ^ a b Abram, David. [2010] 2011. Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology. Vintage. ISBN 978-0-375-71369-9.

- ^ Abram, David (1996). The Spell of the Sensuous. New York: Pantheon Books. p. 303. ISBN 9780679438199.

- ^ Harvey, Graham (2013). The Handbook of Contemporary Animism. London, UK: Routledge.

- ^ Leeming, David A.; Madden, Kathryn; Marlan, Stanton (6 November 2009). Encyclopedia of Psychology and Religion. Springer. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-387-71801-9.

- ^ Harvey (2006), p. 6.

- ^ Quinn, Daniel (2012). "Q and A #400". Ishmael.org. Archived from the original on 23 September 2011.

- ^ Tylor, Edward Burnett (1920). Primitive culture: researches into the development of mythology, philosophy, religion, language, art, and custom. Vol. 2. J. Murray. p. 360.

- ^ Clarke, Peter B., and Peter Beyer, eds. 2009. The World's Religions: Continuities and Transformations. London: Routledge. p. 15.

- ^ Curry, Patrick (2011). Ecological Ethics (2 ed.). Cambridge: Polity. pp. 142–3. ISBN 978-0-7456-5126-2.

- ^ Harrison, Paul A. 2004. Elements of Pantheism. p. 11.

- ^ McColman, Carl. 2002. When Someone You Love Is Wiccan: A Guide to Witchcraft and Paganism for Concerned Friends, Nervous parents, and Curious Co-Workers. p. 97.

- ^ Fernandez-Armesto 2003, p. 138.

- ^ Vontress, Clemmont E. (2005). "Animism: Foundation of Traditional Healing in Sub-Saharan Africa". Integrating Traditional Healing Practices into Counseling and Psychotherapy. SAGE Publications, Inc. pp. 124–137. doi:10.4135/9781452231648. ISBN 9780761930471. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- ^ "Haryana mulls giving marks to class 12 students for planting trees", Hindustan Times, 26 July 2021.

- ^ "Panchvati trees", greenmesg.org, accessed 26 July 2021.

- ^ "Peepal for east amla for west", Times of India, 26 July 2021.

- ^ "National Tree". Government of India. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ^ Kerkar, Rajendra P. (7 June 2009). "Vat-Pournima: Worship of the banyan tree". The Times of India. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ "Mumbai: Women celebrate Vat Purnima at Jogeshwari station". Mid Day. 2 June 2015. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ "Backpacker Backgammon Boards - Banyan Trees". Archived from the original on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ^ "Thimmamma Marrimanu – Anantapur". Anantapur.com. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ^ Rhys Davids, T. W.; Stede, William, eds. (1921–1925). "Nigrodha". The Pali Text Society's Pali-English dictionary. Chipstead, London: Pali Text Society. p. 355. Retrieved 22 November 2008.

- ^ See, for instance, the automated search of the SLTP ed. of the Pali Canon for the root "nigrodh" which results in 243 matches "Search term 'Nigrodh' found in 243 pages in all documents". Bodhgayanews.net. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 22 November 2008.

- ^ See, e.g., SN 46.39, "Trees [Discourse]", trans. by Bhikkhu Bodhi (2000), Connected Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Saṃyutta Nikāya (Boston: Wisdom Publications), pp. 1593, 1906 n. 81; and, Sn 2.5 v. 271 or 272 (Fausböll, 1881, p. 46).

- ^ Bareh, Hamlet, ed. (2001). "Sikkim". Encyclopaedia of North-East India. Vol. 7. Mittal Publications. pp. 284–86. ISBN 81-7099-787-9.

- ^ Torri, Davide (2010). "10. In the Shadow of the Devil: Traditional patterns of Lepcha culture reinterpreted". In Ferrari, Fabrizio (ed.). Health and Religious Rituals in South Asia. Taylor & Francis. pp. 149–156. ISBN 978-1-136-84629-8.

- ^ West, Barbara A., ed. (2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Facts on File Library of World History. Infobase. p. 462. ISBN 978-1-4381-1913-7.

- ^ Zeb, Alam, et al. (2019). "Identifying local actors of deforestation and forest degradation in the Kalasha valleys of Pakistan." Forest Policy and Economics 104: 56–64.

- ^ Lee, Peter H.; De Bary, Wm. Theodore (1996). Sources of Korean tradition. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-10566-5. OCLC 34553561.

- ^ Cole, Fay-Cooper; Gale, Albert (1922). "The Tinguian; Social, Religious, and Economic life of a Philippine tribe". Field Museum of Natural History: Anthropological Series. 14 (2): 235–493.

- ^ Scott, William Henry (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth century Philippine culture and society. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press. ISBN 978-9715501354.

- ^ Demetrio, Francisco R.; Cordero-Fernando, Gilda; Nakpil-Zialcita, Roberto B.; Feleo, Fernando (1991). The Soul Book: Introduction to Philippine pagan religion. Quezon City: GCF Books. ASIN B007FR4S8G.

- ^ R. Ghose (1966), Saivism in Indonesia during the Hindu-Javanese period, The University of Hong Kong Press, pages 16, 123, 494–495, 550–552

- ^ Scott, William Henry (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth Century Philippine Culture and Society. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press. ISBN 971-550-135-4. p. 234.

- ^ de los Reyes y Florentino, Isabelo (2014). History of Ilocos, Volume 1. University of the Philippines Press, 2014. ISBN 9715427294, 9789715427296. p. 83.

- ^ John Crawfurd (2013). History of the Indian Archipelago: Containing an Account of the Manners, Art, Languages, Religions, Institutions, and Commerce of Its Inhabitants. Cambridge University Press. pp. 219–220. ISBN 978-1-108-05615-1.

- ^ Marsden, William (1784). The History of Sumatra: Containing an Account of the Government, Laws, Customs and Manners of the Native Inhabitants. Good Press, 2019.

- ^ Marsden, William (1784). The History of Sumatra: Containing an Account of the Government, Laws, Customs and Manners of the Native Inhabitants, with a Description of the Natural Productions, and a Relation of the Ancient Political State of that Island. p. 255.

- ^ Silliman, Robert Benton (1964). Religious Beliefs and Life at the Beginning of the Spanish Regime in the Philippines: Readings. College of Theology, Silliman University, 1964. p. 46

- ^ Blair, Emma Helen & Robertson, James Alexander. The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898, Volume 40 (of 55): 1690–1691. Chapter XV, p. 106.

- ^ Talbott, Rick F. (2005). Sacred Sacrifice: Ritual Paradigms in Vedic Religion and Early Christianity. Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2005. ISBN 1597523402, 9781597523400. p. 82

- ^ Pomey, François & Tooke, Andrew (1793). The Pantheon: Representing the Fabulous Histories of the Heathen Gods, and the Most Illustrious Heroes of Antiquity, in a Short, Plain, and Familiar Method, by Way of Dialogue, for the Use of Schools. Silvester Doig, 1793. p. 151

- ^ Wallace, Mark I. (2013). "Christian Animism, Green Spirit Theology, and the Global Crisis today". Interdisciplinary and Religio-Cultural Discourses on a Spirit-Filled World. Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/9781137268990.0023. ISBN 9781137268990. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ^ "Theologian Mark Wallace Explores Christian Animism in Recent Book". www.swarthmore.edu. 15 October 2020. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ^ a b Magic and Divination in Early Islam. (2021). Vereinigtes Königreich: Taylor & Francis.

- ^ Pizza, Murphy, and James R. Lewis. 2008. Handbook of Contemporary Paganism. pp. 408–09.

- ^ Hanegraaff, Wouter J. 1998. New Age Religion and Western Culture. p. 199.

- ^ "Shaman." Lexico. Oxford University Press and Dictionary.com. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ Eliadem, Mircea (1972). Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy. Bollingen Series LXXVI. Princeton University Press. pp. 3–7.

- ^ Abram, David (1996). The Spell of the Sensuous. New York: Pantheon Books. pp. 3–29. ISBN 9780679438199.

- ^ Harvey 2005, p. 99.

- ^ Harvey 2005, p. 101.

- ^ Harvey 2005, p. 100.

- ^ Harvey 2005, p. 102.

- ^ Harvey 2005, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Koto, Koray (5 April 2023). "Animism in Anthropological and Psychological Contexts". ULUKAYIN English. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ a b Harvey 2005, p. 104.

- ^ a b Harvey 2005, p. 106.

- ^ Harvey 2005, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Harvey 2005, pp. 106–107.

- ^ a b Harvey 2005, p. 107.

- ^ Harvey 2005, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Harvey 2005, p. 109.

- ^ Harvey 2005, p. 122.

- ^ Herbert, Nick (2002). "Holistic Physics – or – An Introduction to Quantum Tantra". southerncrossreview.org. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ^ Werner J. Krieglstein Compassion: A New Philosophy of the Other 2002, p. 118

- ^ Curtis, Ashley (2018). Error and Loss: A Licence to Enchantment. Zürich: Kommode Verlag. ISBN 978-3952462690.

- ^ Harvey 2005, p. xviii.

- ^ Harvey 2005, p. xix.

- ^ Harvey 2005, p. 50.

- ^ Harvey 2005, p. 55.

- ^ Harvey 2005, p. 64.

- ^ Harvey 2005, p. xxiii.

- ^ Epstein, Robert (31 January 2010). "Spirits, gods and pastel paints: The weird world of master animator Hayao Miyazaki". The Independent. Archived from the original on 7 May 2022. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- ^ Ross, David A. (19 April 2011). "Musings on Miyazaki". Kyoto Journal. Archived from the original on 9 June 2017. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- ^ Ogihara-Schuck, Eriko (16 October 2014). Miyazaki's Animism Abroad: The Reception of Japanese Religious Themes by American and German Audiences. McFarland. ISBN 978-0786472628.

- ^ Bond, Lewis (6 October 2015). "Hayao Miyazaki - The Essence of Humanity". YouTube.com. Channel Criswell. Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

Sources[edit]

- Abram, David (1996). The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-than-Human World. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 9780679438199.

- Adler, Margot (2006) [1979]. Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshippers and Other Pagans in America (Revised ed.). London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-303819-1.

- Armstrong, Karen (1994). A History of God: The 4,000-Year Quest of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Ballantine Books.

- Bird-David, Nurit (2000). ""Animism" Revisited: Personhood, Environment, and Relational Epistemology". Current Anthropology. 41 (S1): 67–91. doi:10.1086/200061.

- Curtis, Ashley (2018). Error and Loss: A Licence to Enchantment. Zürich: Kommode Verlag.

- Dean, Bartholomew (2009). Urarina Society, Cosmology, and History in Peruvian Amazonia. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0-8130-3378-5.

- Fernandez-Armesto, Felipe (2003). Ideas that Changed the World. Dorling Kindersley.

- Forbes, Andrew; Henley, David (2012). "Lamphun's Little-Known Animal Shrines (Animist traditions in Thailand)". Ancient Chiang Mai. Vol. 1. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books.

- Guthrie, Stewart (2000). "On Animism". Current Anthropology. 41 (1): 106–107. doi:10.1086/300107. JSTOR 10.1086/300107. PMID 10593728. S2CID 224796411.

- Harvey, Graham (2005). Animism: Respecting the Living World. London: Hurst & Co. ISBN 978-0-231-13701-0.

- Insoll, Timothy (2004). Archaeology, Ritual, Religion. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-25312-3.

- Lonie, Alexander Charles Oughter (1878). . In Baynes, T. S. (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (9th ed.). New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 55–57.

- Segal, Robert (2004). Myth: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

- Willerslev, Rane (2007). Soul Hunters: Hunting, animism, and personhood among the Siberian Yukaghirs. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520252172.

- "Animism". The Columbia Encyclopedia (6th ed.). Bartleby.com Inc. 2007. Archived from the original on 9 February 2007.

Further reading[edit]

- Abram, David. 2010. Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology (New York: Pantheon Books)

- Badenberg, Robert. 2007. "How about 'Animism'? An Inquiry beyond Label and Legacy." In Mission als Kommunikation: Festschrift für Ursula Wiesemann zu ihrem 75, Geburtstag, edited by K. W. Müller. Nürnberg: VTR (ISBN 978-3-937965-75-8) and Bonn: VKW (ISBN 978-3-938116-33-3).

- Hallowell, Alfred Irving. 1960. "Ojibwa ontology, behavior, and world view." In Culture in History, edited by S. Diamond. (New York: Columbia University Press).

- Reprint: 2002. Pp. 17–49 in Readings in Indigenous Religions, edited by G. Harvey. London: Continuum.

- Harvey, Graham. 2005. Animism: Respecting the Living World. London: Hurst & Co.

- Ingold, Tim. 2006. "Rethinking the animate, re-animating thought." Ethnos 71(1):9–20.

- Käser, Lothar. 2004. Animismus. Eine Einführung in die begrifflichen Grundlagen des Welt- und Menschenbildes traditionaler (ethnischer) Gesellschaften für Entwicklungshelfer und kirchliche Mitarbeiter in Übersee. Bad Liebenzell: Liebenzeller Mission. ISBN 3-921113-61-X.

- mit dem verkürzten Untertitel Einführung in seine begrifflichen Grundlagen auch bei: Erlanger Verlag für Mission und Okumene, Neuendettelsau 2004, ISBN 3-87214-609-2

- Quinn, Daniel. [1996] 1997. The Story of B: An Adventure of the Mind and Spirit. New York: Bantam Books.

- Thomas, Northcote Whitridge (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 53–55.

- Wundt, Wilhelm. 1906. Mythus und Religion, Teil II. Leipzig 1906 (Völkerpsychologie II)

External links[edit]

- Animism, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Animism, Rinri, Modernization; the Base of Japanese Robotics

- Urban Legends Reference Pages: Weight of the Soul

- Animist Network

애니미즘

애니미즘 ( 영어 : animism )이란, 생물 · 무기물을 불문하는 모든 것 속에 영혼 , 혹은 영이 머무르고 있다는 생각. 19세기 후반 영국 인류학자 에드워드 버넷 타일러 가 저서 ' 원시문화 '(1871년 ) 속 에서 사용해 정착시켰다.

어원 [ 편집 ]

이 단어는 라틴어의 애니 마 (anima)에서 유래하며 '기식, 영혼, 생명'이라는 의미이다.

일본어 로는 범령설 , 정령신앙 , 지령신앙 등으로 번역되어 있다.

세계관 [ 편집 ]

타일러는 애니미즘을 '영적 존재에 대한 믿음'으로 하고 종교 적인 것의 최소한의 정의 로 했다. 그에 의하면 제민족의 신 관념은 인격을 투영한 것이라고 한다( 의인화 , 의인관 , 유혜머리즘 ). 현재에도 이 단어는 종교학 에서 접할 때 등 빼놓고는 생각할 수 없는 단어이지만, 한편 타일러의 애니미즘관에 대해서는 말렛(Robert Ranulph Marett) [ ] 2 가「미개인 민족 사이에서는 인격성이 부족한 힘 혹은 생명과 같은 관념도 있다고 하며, 그 애니미즘 이전의 상태를 프리애니즘(pre-animism)[3]이라고 부르고, 같은 개념은 애니마티 즘 ( animatism ) , 바이탈 리즘(vitalism), 다이나미즘(dynamism) [4] 등으로도 불렸다. 또한 연구 자세에 대해서는 유추적 이거나 진화주의적인 등의 비판도 된다.

분류 [ 편집 ]

원시 종교형 [ 편집 ]

원시·미개사회에서 행해지는 종교의 초자연관은 애니미즘적이며, 영적 존재에 대해 주술적으로 관련 된다 . 특정 개조가 없고 의례가 공개적으로 이루어진다. 법·정치·경제·도덕·관습 등과 밀접하게 관계되어 제정이 일치하고, 축제와 경제적 활동이 같은 장소에서 행해지고, 금기(금기)가 법적 또는 도덕적 관념·행동과 겹친다 . 많은 민족 종교가 유사한 특징을 유지한다 [5] [6] .

망령 숭배형·공포형 [ 편집 ]

죽은 사람이 된 조상의 영혼의 존재를 인정하고, 두려움을 두려워 숭배 의 대상으로 하거나, 수호를 바라는 사령 숭배는 미개종교에 있어서의 애니미즘의 한 형태로 되어 있다 [7] . 죽음을 영혼의 영구 이탈로 타계로 향하지만, 사령이나 동물 영은 정해졌을 때 이 세상을 방문하여 사람에게 깨어 건강을 해치게 된다고 한다. 여우, 야코츠키, 오사키츠키는 동물 영빙 의 예이다 [8] .

일본 신화에서는 신대기의 천주여명 , 숭신기의 왜처한 일백습희명 , 중애기의 신공황후 등이 갑자기 신이 걸려( 광의 )하고, 광조난무하는 등 옷깃이 표현되어 왔다 [9] .

미개 사회에서는 샤먼에 의한 주술이 행해지지만, 일본에서는 원령의 두드러짐을 멈추기 위해 신사를 세워 신으로 모셨다 [10] .

신종교 의 대부분이 불행을 ' 선조의 두근두근' 등의 인연화로서 선조 공양과 저주령의 제령, 진혼을 추진하고 있다 [11] . 지진제( 진혼 )의 비용, 조상공양 기도료, 옥꼬리료 등이 관습으로 신사에 지급될 수 있다.

경시청 등에서는 「현관에 들어가자마자 악령이 붙어 있다고 알았다」 「악령이 붙어 잇따라 불행한 일이 일어납니다.」 「 이 화병은 악령을 없애는 힘이 있습니다.」등의 영감상법을 악덕 상법 의 일종으로서 정의하고 있다 [12] .

종교인류학형 [ 편집 ]

종교인류학에서 애니미즘은 많은 원주부족의 신앙체계를 나타내는 말이며[13] 특히 최근에 발전한 조직종교(기독교, 유대교, 이슬람교, 바하이교, 불교 , 식교 등)과의 비교 대조에 사용되었다 [14] . 애니미즘은 인류학자인 에드워드 버넷 타일러 가 1871년에 발표한 저서 ' 미개문화 (영:Primitive Culture)' [15] 중에서 '영혼과 그 밖의 정신적인 존재 전반에 관한 일반적인 교리' 로 정의되었다.

타일러에게 애니미즘은 가장 초기 종교의 형태이며, 단계적으로 발전해 온 종교의 진화의 틀 안에 위치하고, 결국 인류가 과학적 합리성을 요구하여 종교를 완전히 거절하는 것 된다고 생각했다 [16] . 이와 같이 타일러에 있어서 애니미즘은 모든 종교가 성장하는 원흉이 된 기초적인 에러였다 [16] .

애니미즘의 진화론적 해석은 각 방면에서 비판되고 있으며, 오늘날은 문제 밖으로 생각되고 있다 [8] .

특징 [ 편집 ]

애니미즘이 단순한 단일 종교적 신념인지 [17] , 또는 전세계의 다양한 문화권에서 발견되는 많은 다양한 신화로 이루어진 그 자체가 하나의 세계관인지[ 18 ] 의견 차이가 계속된다 (일반적인 합의는 얻어지지 않았다). 이것은 또한 애니미즘이 윤리적 주장을 할 것인지 아니면 애니미즘이 윤리 문제를 완전히 무시하는지에 대한 논쟁을 야기한다 [19 ] .

범신론과의 차이 [ 편집 ]

애니미즘은 범신론 과는 다르지만 이 두 가지는 혼동될 수 있다. 주된 차이점 중 하나는 애니미즘은 모든 것이 정신적인 성질(영혼, 영 등)을 가진다고 믿지만, 범신론자처럼 존재하는 모든 것의 정신적 본질이 통일 되어 있다 라고는 생각하지 않는 것이다( 일원론 ). 애니미즘에서는 개개의 영혼의 독자성을 전제로 하지만, 범신론에서는, 모든 것은 각각의 정신이나 영혼을 가지는 것이 아니라, 같은 본질( 영 :essence, 라틴:essentia)을 공유하고 있다 [ 20] [21] .

범심론과의 차이 [ 편집 ]

애니미즘은 모든 것에 영혼이 있다고 주장하고, 물활론은 모든 것이 살아 있다고 주장한다 [22] :149 [23] . 이러한 입장을 범심론으로 해석하는 것에 대해서는 현대의 학술계에서는 지지되지 않았다 [24] . 현대의 범심론 자는 이런 이론으로부터 거리를 두려고 하며, 경험의 편재성과 마음과 인지의 편재성 사이에 구별을 하도록 주의하고 있다[25 ] [ 26] .

저주에 대한 숭배 [ 편집 ]

- 저주 숭배

- 동식물이나 기타 사물에 인격적인 영혼, 영신이 머무르는 애니미즘은, 비인격적인 초상현상, 초자연적인 저력을 숭배하는 마나이즘(주력 숭배)과는 구별된다[27] [ 28 ] .

- 저주 숭배

- 저주 숭배 (페티시즘)는 미개 사회, 고대 사회, 미개종교에서 볼 수 있는 신앙으로, 저주가 인간에게 숙복을 가져다준다고 믿고 의례의 대상으로 하는 것이다[29][ 30 ] . 인공물이나 간단하게 가공한 자연물에 대한 숭배의 총칭으로 되어 있고 [31] , 애니미즘과도 깊은 관계를 가진다 [8] .

현존하는 문화의 애니메이션 [ 편집 ]

- 애니트 ("조상의 영"의 뜻): 바바이란이라고 불리는 여성 또는 여성화된 남성 샤먼에게 이끌린 필리핀의 다양한 원주민 들의 샤머니즘 적 민속 종교 . 물질세계와 함께 존재하고 물질세계와 상호작용하는 정신세계에 대한 믿음과 바위나 나무, 동물과 인간, 자연현상에 이르기까지 모든 것에 정신이 있다는 믿음을 포함한다[32][ 33 ] .

- 드라비다의 민속 종교 (원시 샤이바교/민속 샤이바교): 드라비다 민족의 전통적인 애니미즘, 다신교, 일부 샤마니즘의 민속 종교.

- 베다교와 비베다계 동물: 자이나교와 불교가 도입되기 전의 아리아인과 다른 북인도인의 전통적인 애니메이션, 다신교, 일부 샤머니즘의 민속 종교. 현재의 힌두교는 역사적인 베다교와는 분명히 다른 별종교이지만, 힌두교를 형성한 전통의 하나이다[note 1 ] .

- 파키스탄 북부의 카라시족 은 고대의 애니미즘 종교를 믿고 있다 [34] .

- 한국 의 샤머니즘 (Mu 또는 Muism으로도 알려져 있다)은 많은 애니미즘적 측면을 가지고 있다 [35] .

- 문 (Munism 또는 Bonthingism이라고도 함) : 렙차족 의 전통적인 다신교, 동물주의, 샤머니즘, 싱크레틱 종교 [36] [37] [38] .

- 신도 (류큐 종교를 포함): 일본의 전통적인 민간 종교로, 많은 애니미즘적인 측면을 가지고 있다 [39] . 우메하라 맹 은 타일러의 원시 종교의 학설을 인정하고 일본의 신도와 불교가 원시 종교인 애니미즘의 원리를 따르고 있다고 했지만, 애니미즘을 인류에게 필요한 세계관이라고 주장했다[40 ] .

- 태평양 지역( 폴리네시아 삼각권, 멜라네시아 , 미크로네시아 )의 마나이즘 . 마르키스 제도 의 티키 상과 부활절 섬 의 모아 이상은 애니미즘과 토테미즘 신앙의 잔재이다. .

- 아프리카의 전통 종교 : 사하라 이남의 아프리카의 대부분의 종교적 전통에서 기본적으로 다신교적, 샤머니즘적 요소와 조상 숭배를 포함한 동물의 복잡한 형태가 유지되어있다 [41 ] .

- 북아프리카의 전통적인 벨벨인 종교 와 이슬람 이전 아랍인 종교: 벨벨인과 아랍인의 전통적인 다신교, 동물주의, 드물게 샤머니즘 종교.

- 에코페이건을 비롯한 여러 네오페이건 그룹은 자신을 동물로 표현하고 있는데, 이는 인간이 세계와 우주를 공유하는 다양한 생물과 정령의 커뮤니티를 존중한다는 것을 의미합니다. 있다 [42] .

- 뉴 에이지 운동은 자연의 정령의 존재를 주장하는 애니미즘적인 특징을 잘 보여준다 [43] .

샤머니즘 [ 편집 ]

샤먼은 선령과 악령의 세계에 접근하여 영향력을 가진 것으로 생각되는 사람으로, 전형적으로 의식시 변압기 상태로 들어가 운세와 치유를하는 사람입니다. 이다 [45] .

밀차 엘리에데 에 따르면, 샤머니즘은 샤먼이 인간계와 영계 사이의 중개자 또는 메신저라는 전제를 포함하고 있다. 무당은 영혼을 복구하여 질병과 질병을 치료한다고합니다. 영혼과 정신에 영향을 준 외상을 완화시켜 개인의 육체의 균형과 완전성을 되찾는다. 샤먼은 또한 커뮤니티를 괴롭히는 문제에 대한 해결책을 얻기 위해 초자연적인 영역과 차원에 들어갑니다. 샤먼은 헤매는 영혼에 인도를 주거나 이질적인 요소에 의한 인간의 영혼의 병을 개선하기 위해 다른 세계와 차원을 방문할 수도 있다. 샤먼은 주로 정신 세계에서 활동하고, 그것이 인간 세계에 영향을 미친다. 균형을 회복함으로써 질병이 해소된다고 주장한다 [46] .

데이비드 에이브람 은 에리아르데가 제창한 샤먼의 역할에 대해 초자연적이지 않고, 보다 생태학적 이해를 명확히 하고 있다. 인도네시아 , 네팔 , 미국 대륙에서 자신의 필드 리서치를 바탕으로, 에이브람은 애니미즘 문화에서 샤먼은 주로 인간 사회와 인간 이상으로 활동적인 기관인 지역의 동물, 식물, 지형( 산, 강, 숲, 바람, 날씨 패턴, 이들 모두 고유의 감각이 있다고 여겨진다) 사이의 중개자 역할을 제안합니다. 그러므로 인간사회에서의 개별적인 부조(밸런스의 무너짐)를 치유하는 샤먼의 능력은 인간사회와 그 사회가 통합되어 있는 생물의 보다 넓은 집합체 사이의 호혜관계의 밸런스를 취한다는 것보다 지속적인 실천의 부산물이라고 한다.

안다만 제도의 종교 [ 편집 ]

안다만 제도 사람들의 종교는 「애니미즘적 일신교」라고도 불리며, 우주를 창조한 파르가라는 유일한 신을 제일로 믿고 있다[47 ] . 파르가는 자연 현상을 의인화한 것으로 알려져 있다 [48] .

아브라함의 종교 [ 편집 ]

구약 성서 와 지혜 문학 에서는 하나님의 편재성 (Omnipresence) (예레미야 23:24 ) (잠언 15:3 ) (열왕기 8:27 )이 설교되어 있지만, 기독교 신학자 마크 와라스는 동물, 나무, 바위 등 지구상의 모든 것에 하나님이 존재한다고 논하고 있다 [49] .

토테미즘과의 관계, 다른 사회와의 비교 : 필립 데스코라 설 [ 편집 ]

애니미즘은 토테미즘 과 깊이 관련되어 있다고 여겨진다 [8] . 필립 데스코라 는 "자연과 문화를 넘어"속에서 예를 들어 아마존 분지 의 어츄얼족 사회에서 노마드 사회 특유의 애니미즘적 사고와 정주형 사회에서 보는 토테미즘적 사고의 혼교적 요소가 많다고 생각하면 분석했다. 즉, 애니마(정신)가 인간과 비인간 사이를 왕환하는 애니미즘과, 애니마가 인간 집단과 비인간적 상징을 연결하고 있는 토테미즘이라는 차이점이 있지만[50], 기본적으로는 애니미즘 에서도 토테미즘에서도 인간이 다른 동물이나 식물, 자연의 힘과 거의 동등한 입장에 있다는 공통점을 알 수 있다[ 51] .

게다가 데스콜라는 모든 사회를 분석하면 애니미즘, 토테미즘 , 유추주의(아나로지즘) 및 자연주의 (내츄럴리스즘)로 구성된 4개의 '동일화의 형태'로 구별할 수 있다고 한다.

동일화(Identité)와 제형(Différentiation)은 스스로와 다른 것과의 경계를 정의하는 방법이다. Intériorité와 Physicalité는 내면(정신)과 외모(신체)의 차원이 된다.

이 구별에서, 예를 들어 서구의 근대 사회가 자연주의적 (Naturalisme)이라고 한다면, 그 이외의 사회는 애니미즘적이거나, 토테미즘적인 사회인가, 그것인가 분석적적인 사회(주로 중세의 서유럽 보는 자연주의적인 사회의 전신, 혹은 중국·인도 등의 유추주의적인 사회)가 된다.

우선 애니미즘을 특징짓는 것은 비인간이라는 사회적 속성에 의해 여러 관계의 카테고리화가 가능하게 되는 사회이다. 즉 여기에서는 비인간이 관계의 항이 되고 있다. 토테미즘 을 특징짓는 것은 비인간끼리의 불연속성에 의해 인간의 비연속성을 사고할 수 있게 되는 사회이다. 이러한 사회에 있어서는, 비인간이란 기호와 같은 것이다.

한편, 자연주의란 , “자연이 존재한다는 단순한 믿음, 추억이며, 바꾸어 말하면, 몇 가지 실재가 존재하는 것이나, 그 전개는, 인간의 의지의 효과의 외측에 있는 원리에 의하고 있다고 하는 것입니다. 플라톤이나 아리스토텔레스 이후의 서양 코스몰로지에 전형적인 자연주의는 특정 존재론적 영역, 즉 초월론적 심급을 따르는 것인가, 세계의 구조에 내재하고 있는 이유 없어서는 아무것도 생기지 않는다고 하는 질서 혹은 필연성의 장을 산출한다.자연주의가 우리의 코스몰로지의 주도적 원리이며, 우리의 공통감각과 과학적 원리 유사 침투하고 있는 한 그런 자연주의가 우리에게는 우리의 인식론, 특히 동일화의 다른 양식에 대한 견해와 시선을 구조화하고있는 "자연"과 같은 것이라 할 수 있다고 가정합니다. 이다” [52] .

즉, 서양이 가진 자연주의는 인간의 다른 것들과 세계를 향한 견해나 시선을 규정하고 있어, 「자연」을 외적인 것으로 간주하고, 애니미즘이나 토테미즘과는 근본적으로 다른 존재론 에 근거하는 것이 된다.

주석 [ 편집 ]

- ↑ Michaels (2004 , p. 38): "힌두교에서의 베다 종교의 유산은 일반적으로 과대평가되고 있다. 신화의 영향은 확실히 크지만, 종교 용어는 바뀌었다. 힌두교의 주요한 모든 용어는 베다에 존재하지 않거나 완전히 다른 의미를 지니고 있습니다. 베다 종교는 행위의 보상과 함께 윤리적 영혼의 움직임 ( karma ), 주기적 세계의 파괴, 일생 동안 의 구제 생각( jivanmukti; moksa; nirvana )을 가지지 않는다.세계를 환영으로 간주하는 생각( maya )은, 고대 인도의 풍조에 반하고 있어, 전능의 창조신은 리그 베다의 후기의 찬송가에만 등장한다. 또한 베다 종교에는 카스트 제도, 과부의 화장, 재혼 금지, 신들의 동상과 사원, 푸자 예배, 요가, 순례, 채식주의, 소의 신성함, 삶의 단계의 교리(asrama) 등이 알려져 있다 그렇지 않거나 그들이 시작되었을 때에만 알려지는 것은 없었습니다. 따라서 베다 종교와 힌두 종교 사이에는 전환점이 있다고 생각하는 것이 합리적 일 것입니다."

" Vedic Hinduism Harvard University. pp. 3 (1992년). 2021년 6월 29일에 확인함. : "... 이들을 베다계 힌두교라고 부르는 것은 형용 모순( 무착어법)라고 해도 좋다. 왜냐하면 베다 종교는 일반적으로 힌두교라고 불리는 것과는 매우 다르기 때문이다. 적어도 고대 히브리어 종교는 중세와 현대 기독교 종교와는 다르다. 그러나 베다 종교는 힌두교의 전신으로 취급할 수 있다. See

also Halbfass 1991 , pp. 1-2

각주 [ 편집 ]

- ↑ 『말렛』 - 코트뱅크

- ↑ 『로버트 라날프 말렛』 - 코트뱅크

- ^ ' 프레애니미즘 ' - 코트뱅크

- ↑ 『역동설』 - 코트뱅크

- ^ 학교 회관 2021b , p. "원시 종교".

- ^ 학교 회관 2021c , p. "원시 종교".

- ↑ 쇼가쿠칸 2021a , p. 사망 예배.

- ^ a b c d 쇼가쿠칸 2021d , p. "애니미즘".

- ↑ 평범한 회사 2021b , p.

- ↑ Britanica Japan 2021c , p. "원령".

- ^ 일반 사회 2021c , p. "조상 지원".

- ↑ 악질상법 경시청

- ↑ 데이빗 힉스 (2010). 의례와 믿음: 종교 인류학 (3판)의 읽기. 로먼 알타미라 . 피. 359. "타일러의 최초의 종교인 애니미즘 개념에는 초기 호모 사피엔스가 동물과 식물에 영혼을 부여했다는 가정이 포함되었습니다 ..."

- ↑ “ Animism ”. ELMAR Project (University of Cumbria) (1998–1999). 3- June 2021 보기.

- ^ EB (1878) .

- ^ a b Harvey 2005년 , p. 6.

- ^ 데이비드 A. 리밍; 캐스린 매든; Stanton Marlan(2009년 11월 6일). 심리학과 종교 의 백과사전 뛰는 것. 피. 42. ISBN 978-0-387-71801-9

- ^ Harvey (2006), p. 6.

- ↑ 에드워드 버넷 타일러(1920). 원시 문화: 신화, 철학, 종교, 언어, 예술 및 관습의 발전을 연구합니다 . J. 머레이. 피. 360

- ^ Harrison, Paul A. 2004. 범신론의 요소 . 피. 11.

- ↑ 칼 맥콜먼. 2002. 당신이 사랑하는 누군가가 Wiccan일 때: 걱정하는 친구, 신경질적인 부모, 호기심 많은 동료를 위한 주술과 이교에 대한 안내서 . 피. 97.

- ^ 스크르비나, 데이빗. (2005). 서양의 범심론 . MIT 프레스. ISBN 0-262-19522-4

- ^ 카루스, 폴. (1893). “범심론과 범생물주의.” 더 모니스트 . Vol. 3, No. 2. pp. 234–257. JSTOR 27897062

- ↑ “ Panpsychism ”. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy . 2019년 5월 1일에 확인함.

- ↑ Goff, Philip; Seager, William; Allen-Hermanson, Sean (2017). "Panpsychism" . In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy . 2018년 9월 15일에 확인함 .

- ↑ Chalmers, David (2017). "The Combination Problem for Panpsychism" (PDF) . In Brüntrup, Godehard; Jaskolla, Ludwig (eds.). Panpsychism: Contemporary Perspectives . New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 179–214 . 2019년 4월 28일에 확인함 .

- ↑ Britanica Japan 2021a , p. "자연 숭배".

- ↑ Britanica Japan 2021b , p. "정령 숭배".

- ↑ 쇼가쿠칸 2021e , p. "주물 숭배".

- ↑ 쇼가쿠칸 2021f , p. "주물 숭배".

- ↑ 쇼가쿠칸 2021g , p. "페티시즘".

- ↑ 스콧, 윌리엄 헨리 (1994). Barangay: 16세기 필리핀 문화와 사회 . 케손 시티: Ateneo de Manila University Press. ISBN 978-9715501354

- ^ Demetrius, Francis R.; Lamb-Fernand, 길다 ; 낙필-지알시타, 로버트 B.; 펠레오, 페르디난드 (1991). 소울 북: 필리핀 이교 소개 . Quezon City: GCF 도서. 솔트 B007FR4S8G

- ^ Zeb, Alam, 외 . (2019). " 파키스탄의 Kalasha 계곡에서 삼림 벌채 및 삼림 황폐화 의 지역 행위자를 식별합니다." 산림정책과 경제학 104 : 56–64.

- ^ Lee, Peter H.; 드 배리, Wm. 시어 도어 (1996). 한국 전통의 근원 . 뉴욕: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-10566-5 . OCLC 34553561

- ^ Bareh, Hamlet, 편집. (2001). "시킴" . 북동 인도의 백과사전 . 7 . 미탈 간행물. 284-86쪽. ISBN 81-7099-787-9。

- ↑ 데이빗 토리 (2010). “10. 악마의 그늘에서: 재해석된 레프차 문화의 전통 패턴” . 페라리에서 파브리지오. 남아시아 의 건강과 종교 의식 테일러 & 프랜시스. 100-1페이지 149–156. ISBN 978-1-136-84629-8

- ^ West, Barbara A., ed (2009). 아시아 및 오세아니아 민족의 백과사전 . 세계사 파일 라이브러리에 대한 사실. 인포베이스 퍼블리싱. 피. 462. ISBN 978-1-4381-1913-7

- ^ Nelson 1996년 , p. 7; 피켄 2011 , p. 40.

- ↑ 우메하라 맹, 국제 일본 문화 연구 센터 기요권 1,1989-05-21, p.13-23

- ^ Vontress, Clemmont E. (2005). 상담 및 심리 치료에 전통적인 치유 방법 통합 . SAGE Publications, Inc.. 124–137페이지

- ^ 피자, 머피, 제임스 R. 루이스 . 2008. 현대 이교 핸드북 . 408-09쪽.

- ^ Hanegraaff, Wouter J. 1998. 뉴에이지 종교와 서양 문화 . 피. 199.

- ^ 페이-쿠퍼 콜; 앨버트 게일(1922). “팅귀안; 필리핀 부족의 사회, 종교, 경제 생활” . 필드 자연사 박물관: 인류학 시리즈 14 (2): 235–493 .

- ^ " 샤먼 ." 렉시코 . 옥스포드 대학 출판부 및 Dictionary.com . 2020년 7월 25일에 확인함.

- ^ Eliadem Mircea . 1972. 샤머니즘: 황홀경의 고풍스러운 기술 , Bollingen Series LXXVI. 프린스턴 대학교 출판부. 3~7쪽.

- ↑ AR, Radcliffe-Brown (2013년 11월 14일). 안다만 섬 주민들. 케임브리지 대학 출판부. 피. 161. ISBN 978-1-107-62556-3 .

- ↑ https://www.webindia123.com/territories/andaman/people/intro.htm

- ↑ “ Theologian Mark Wallace Explores Christian Animism in Recent Book ” (영어). www.swarthmore.edu (2020년 10월 15일). 2020년 12월 8일에 확인함.

- ↑ 필립 데스코라『자연과 문화를 넘어』(총서 인류학의 전회), 수성사, 2020년

- ↑ 페르난데즈-아르메스토, 필립 (2003). 세상을 바꾼 아이디어. 돌링 킨더슬리, p. 138.

- ^ Philippe Descola, 2001년 3월 29일 파리, College de France, 자연 인류학 의장을 위한 College de France에서의 취임 강연 ISBN 2-7226-0061-7 비디오

참고 문헌 · 관련 서적 [ 편집 ]

- 에드워드 타일러 '원시 문화' 비 지붕 안정역, 성신서방, 1962년

- 필립 데스코라 "자연과 문화를 넘어"(총서 인류학의 전회), 수성사, 2020년

- 필립·데스코라· 아키도 토모야 “교착하는 세계 자연과 문화의 탈구축” 교토대학 학술 출판회, 2018년

- 아야베 항웅편『문화인류학의 명저 50』평범사, 1994년. ISBN 4-582-48113-2

- 마이클스, 악셀(2004). 힌두교. 과거와 현재 . 뉴저지 주 프린스턴: Princeton University Press

- 로니, 알렉산더 찰스 아우터(1878). . In Baynes, TS(에디션). 브리태니커 백과사전 (영어). 2 (9판). 뉴욕: Charles Scribner의 아들들. 55~57쪽.

- 하비, 그레이엄 (2005). 애니미즘: 살아있는 세계 존중 . 런던: Hurst & Co. ISBN 978-0-231-13701-0

- 넬슨, 존 K. (1996). 신사 생활의 1년 . 시애틀과 런던: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-97500-9

- 넬슨, 존 K. (2000). 지속되는 정체성: 현대 일본의 신도의 모습 . 호놀룰루: 하와이 대학교 출판부. ISBN 978-0-8248-2259-0

- 피켄, 스튜어트 DB (1994). 신도의 필수 요소: 주요 가르침에 대한 분석적 안내 . 웨스트포트와 런던: 그린우드. ISBN 978-0-313-26431-3

- 피켄, 스튜어트 DB(2011). 신도 역사 사전 (제2판). Lanham: 허수아비 프레스. ISBN 978-0-8108-7172-4

- 쇼가쿠칸 “애니미즘” “일본 대백과 전서(닛포니카)” 쇼가쿠칸, 코트뱅크, 2021d. 일본 대백과 전서 (닛포니카) " 애니미즘 "- 코트 뱅크

- 쇼가쿠칸 “사령 숭배” “정선판 일본 국어 대사전” 쇼가쿠칸, 코트뱅크, 2021a. 정선판 일본어대사전 『사령숭배』 - 코트뱅크

- 쇼가쿠칸 “원시 종교” “일본 대백과 전서(닛포니카)” 쇼가쿠칸, 코트뱅크, 2021b. 일본대백과전서(닛포니카) 『원시종교』 - 코트뱅크

- 쇼가쿠칸 “원시 종교” “디지털 대사천” 쇼가쿠칸, 코트뱅크, 2021c. 디지털 대사천 “ 원시 종교 ” - 코트뱅크

- 평범사 「신가카리」 「세계대백과사전 제2판」평범사, 코트뱅크, 2021b. 세계대백과사전 제2판 『신가카리』 - 코트뱅크

- 브리타니카 재팬「자연 숭배」 「브리타니카 국제대백과사전 소항목사전」 브리타니카 재팬, 코트뱅크, 2021a. 브리타니카 국제대백과사전 소항목사전 “ 자연숭배 ” - 코트뱅크

- 브리타니카 재팬 「정령 숭배」 「브리타니카 국제대백과사전 소항목사전」 브리타니카 재팬, 코트뱅크, 2021a. 브리타니카 국제대백과사전 소항목사전 「정령숭배」 - 코트뱅크

- 브리타니카 재팬 '원령' '브리타니카 국제대백과사전 소항목사전' 브리타니카 재팬, 코트뱅크, 2021c. 브리타니카 국제대백과사전 소항목사전 ' 원령 ' - 코트뱅크

- 평범사 “선조공양” “세계대백과사전 제2판” 평범사, 코트뱅크, 2021c. 세계대백과사전 제2판 『선조공양』 - 코트뱅크

- 쇼가쿠칸 「주물 숭배」 「정선판 일본어 대사전」 쇼가쿠칸, 코트뱅크, 2021e. 정선판 일본어대사전 「주물 숭배」 - 코트뱅크

- 쇼가쿠칸 “주물 숭배” “디지털 대사천” 쇼가쿠칸, 코트뱅크, 2021f. 디지털 대사천 “ 주물 숭배 ”- 코트뱅크

- 쇼가쿠칸 「페티시즘」 「정선판 일본어대사전」 쇼가쿠칸, 코트뱅크, 2021g. 정선판 일본어대사전 「페티시즘」 - 코트뱅크

관련 항목 [ 편집 ]

외부 링크

애니미즘

애니미즘(영어: animism ← 라틴어: anima('숨, 생명, 영혼'이라는 뜻)에서 파생)은 해, 달, 별, 강과 같은 자연계의 모든 사물과 불, 바람, 벼락, 폭풍우, 계절 등과 같은 무생물적 자연 현상과 생물(동·식물) 모두에 생명이 있다고 보고, 그것의 영혼을 인정하여 인간처럼 의식, 욕구, 느낌 등이 존재하다고 믿는 세계관 또는 원시 신앙이다.[1] 달리 말해, 애니미즘은 각각의 사물과 현상 즉, 무생물계에도 정령(精靈) 또는 영혼, 즉 '눈에 보이지 않는 어떤 영적인 힘 또는 존재'가 깃들어 있다고 믿는 것이다.[2]

이 낱말은 "숨, 삶, 영혼"이라는 의미를 갖는 라틴어 anima에서 유래되었으며, 종교의 기원에 관해 제출된 여러 이론 가운데 하나이다. 한때 서구권에서 종교에 관한 진화적 시각이 유행하였는데, 지금은 폐기된 이 관점에 따르면 종교는 애니미즘에서 기원하여 다신교와 단일신교를 차례로 거쳐 일신교로 발전한다. 이 발전 도식에서, 다신교는 정령들이 자신만의 특징적인 형태와 능력을 가진, 특정 사물이나 현상에만 깃들어 있지 않은 독자적인 신으로 변화하는 단계이다. 단일신교는 신들 사이에 계층 분화가 일어나고 가장 큰 힘을 가진 신이 최고신이 되어 신앙의 주된 대상이 되는 단계이다. 일신교는 단일신교의 과정이 심화되어 단 하나의 전능한 신, 즉, 유일신만이 존재하고 나머지는 그것에 흡수되거나 그것의 사자(使者)가 되는 단계이다.[3]

각주[편집]

| 위키미디어 공용에 관련된 미디어 분류가 있습니다. |