shamanism

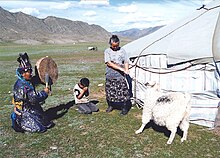

In a narrower sense, shamanism refers to the traditional ethnic religions of the cultural area of Siberia ( Nenets , Yakuts , Altai , Buryats , Evenks , also European Sami and others), for which the presence of shamans was considered by European researchers of the expansion period to be an essential common characteristic. [1] For better differentiation, these religions are often called "classical shamanism" or "Siberian animism". [2]

In a broader sense , shamanism means all scientific concepts that posit the cross-cultural existence of shamanism due to similar practices of spiritual specialists in different traditional societies . According to László Vajda [3] and Jane Monnig Atkinson [A 1] , due to the large number of different concepts, it would be more appropriate to speak of shamanisms in the plural.

In many traditional worldviews , Siberian shamans and various necromancers from other ethnic groups – who are also often referred to generically as shamans – allegedly had or still have influence over the powers of the afterlife . They used their abilities mainly for the benefit of the community , in order to restore the "cosmic harmony" between this world and the afterlife in crisis situations that seemed insoluble. In this broad sense, shamanism refers to a series of vaguely defined phenomena "between religion and healing rituals ". [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9][Note 1]

A more general definition is not possible because the definition contains different perspectives from the perspective of ethnology , cultural anthropology , religious studies , archaeology , sociology and psychology . [10] [11] One of the consequences of this is that information on the spatial and temporal distribution of "shamanisms" differ considerably and in many cases are disputed. [12] [13] [14] The American ethnologist Clifford Geertztherefore already in the 1960s denied the "western idealistic construct shamanism" any explanatory value. [A2]

They only agree on the "narrow definition" of classic Siberian shamanism - the starting point of the first "shamanisms". Above all, this includes the precise description of the ritual ecstasy practiced there , a largely identical ethnic religion and a similar cosmology and way of life. [15] [11] [16]

According to broader definitions, until the 1980s, shamanism was considered an early, cross-cultural stage of development of any religion. [15] Above all, the concept of core shamanism by Michael Harner should be mentioned here. However, this interpretation is now considered to be incapable of consensus. [14] Since the 1990s, the aspect of "healing" has often been the focus of interest (and the respective definition). [10]

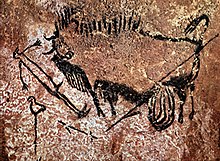

In contrast, the Indologist Michael Witzel posits that given the similarity of Australian, Andaman , Indian and African initiation rituals to the corresponding Siberian rituals involving the phenomena of rising heat, trances ( dreamers ), ecstasy and collapse, symbolic death and rebirth, usage psychoactive drugs, taboo-keeping, magic and healing, gave an older prototype of shamanism. This spread with the out-of-Africa migration of modern humans along the coasts of the Indian Ocean and early also to Eurasia and North America. This is supported by late Palaeolithic bear cultsand petroglyphs as in Les trois frères (fig. see below). Siberian shamanism represents a younger evolution of this prototype (with fur clothing, drum, etc.); he had a secondary influence on the North American hunter cultures through further waves of migration. Instead of sacrificing wild animals, which the shaman first asks for permission to kill or from which he apologizes for the act (as in the bear cults of the shamans of the Ainu , Aleut , and Transbaikal peoples), later domesticated animals like that reindeer (in Siberia) or dogs (as in Russia or India). [17] In this respect, Witzel follows Walter and Fridman's broad phenomenological definition of shamanism.[18]

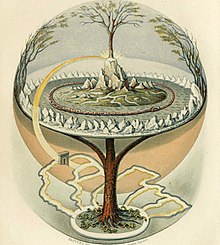

Since the classic shamanism of Siberia already shows a number of variants, many authors criticize more far-reaching geographical or historical interpretations that consider such phenomena out of their cultural context and generalize them as speculative. [19] [13] In contemporary literature - popular scientific (especially esoteric) books, but also scientific writings - it is often not made clear in this context to which ethnic groups specific shamanic practices refer, so that regional (often Siberian ) Phenomena are also located in other cultures, in whose traditions they are actually alien. Examples of this are the world tree and the entireshamanic cosmology : mythological concepts rooted in Eurasia that are equated here with similar archetypes from other parts of the world, thus creating the misleading image of a unified shamanism. [13] Witzel, however, sees in the Eurasian (Germanic, Indian, Japanese, etc.) idea of the tree of life that has to be climbed, or in the world tree, only an analogy to the older idea of the shaman's flight, which has nothing to do with other tree myths. [20]

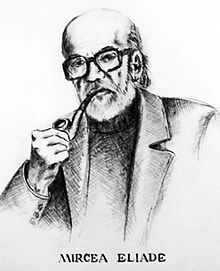

In particular, the highly successful books by Mircea Eliade , Carlos Castaneda , and Harner have generated the "modern myth of shamanism," which suggests that it is a universal and homologously evolved religio-spiritual phenomenon. In view of the great interest in the population [21] , some authors point out that shamanism is not a uniform ideology or religion of certain cultures . Rather, it is a scientific construct of EurocentricPerspective to compare and classify similar phenomena around necromancers of different origins. [14] [22] [23]

Etymology [ edit | edit source ]

According to most authors, the term shamanism is derived from the Siberian word shaman , which the Tungusic peoples use to describe their necromancers. [24] The word probably derives from the Evenk (i.e. Tungusic ) šaman , whose further etymology is disputed. It is possibly based on the Manjuric verb sambi , "to know, to know, to see through". The older term shamanism does not refer to the scientific concepts, but only to the existence of necromancers in different cultures, withoutto establish certain connections. [25]

(For more information see: Etymology in the article "Shaman")

Shamans and Shamanism [ edit | edit source ]

In general, the term shaman , borrowed from Siberia, is used to refer to spiritual specialists who have (supposedly) " magical " abilities as intermediaries to the spirit world . [26] [27] [10] Such necromancers are part of many ethnic religions , but also some folk -religious forms of world religions. [12] Shamans still play an important role today, especially in some indigenous or traditional local communities (→"Traditional contemporary spiritual specialists in the light of history" in the article Shaman ) .

Since the first descriptions of such spiritual experts in different societies, European ethnologists have tried to recognize similarities and possible patterns and to deduce connections.

The existence of a shaman is undoubtedly a prerequisite for any thesis of shamanism, but not necessarily the central idea. It is often more about religious beliefs, rites and traditions, [28] than about the prominent role of the shaman. In this respect, the various, conceptually different definitions arose. [3]

The shamans are integrated into the living environment and natural environment of their respective cultures and cannot be regarded as the embodiment of a specific shamanistic religion or cosmology. [29] Thus, shamanism is closely related to healing the sick, to funeral rites, and to hunting magic . Michael Lütge compares his role with the " anamnesis of the parish priest during a condolence visit", who tracked down biographical fragments of the deceased, which "blow over" him from the closer circle of relatives. In other situations, he practices "anticipatory[...] hunting propaedeutics similar to school fire safety exercises". [30]

History of Science [ edit | edit source ]

"Shamanism is not a uniform religion, but a cross-cultural form of religious perception and practice."

There have been detailed accounts of the shamans of Siberia and their practices since the late 17th century. The attitude of the Europeans oscillated between admiration and contempt several times. At first, these reports aroused only resentment and incomprehension. [32] In the course of German Romanticism , the pendulum swung in the opposite direction and shamans were glorified as "charismatic geniuses".

Scientific research in the context of ethnology is also characterized by this large discrepancy: First, shamans were regarded as pathologically psychotic and their forms of expression were described as "arctic hysteria". [33] Later, epilepsy or schizophrenia were related to shamanism. [34]

But as early as the beginning of the 20th century, the special social position of the Siberian "Master of Spirits" and the legitimacy of his actions in the respective cultural and historical context were examined in detail from a sociological and psychological point of view: He was legitimized to carry out techniques that other members of society in the ruled everyday life. During his field research among the Evenks and Manchu, Shirokogoroff found that shamans were often neurotic people; However, he distanced himself from the then widespread explanation model for the actions of the shamans: The trances , ritual ecstasies or "fits" of the shamans are not an expression of hysteria orobsession , but well-staged, culturally coded performative solutions to conflicts, which e.g. B. were used against the Russian foreign rule [35] - so historically specifically pronounced phenomena. In the Soviet Union, for example, shamans were denigrated as charlatans who allegedly wanted to gain power with the help of religious rituals. [36]

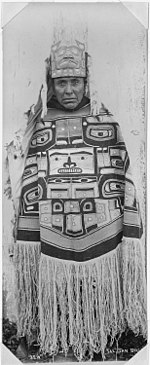

The "ghost men" or "magicians" of North America repeatedly took on the role of political leaders in the course of the westward migration of the white colonists and placed themselves at the forefront of nativist movements. As early as 1680, a temporarily successful uprising of the Tewa in New Mexico against the Spanish colonists was organized by the medicine man El Popé . In African revolts against the colonizers, spiritual mediators often played a role as leaders, such as the healer Kinjikitile Ngwale , said to be possessed by the spirit Hongo of the snake god in the Maji Maji rebellion1905-1907. Those who showed obsession with a Hongo could greatly influence the religion and politics of their ethnic group. Lévi-Strauss also reports on shamans who competed with tribal leaders. [37]

With the abandonment of the German Kulturkreis theory, which was frowned upon as racist , and the evolutionist "stage ideology" in the Marxist -influenced states, a more respectful attitude towards the cultures of the so-called primitive peoples prevailed in ethnology. [38]

In North America, at the turn of the 20th century, there was a certain romanticization and idealization of the North American Indian cultures and with them the spiritual-religious ideas, which were soon associated with the ecstatic shamanism of Siberia and later also with the occult practices of South America up to which the Selk'nam on Tierra del Fuego were combined as a shamanistic complex .

It was the Romanian religious scholar and novelist Mircea Eliade who decisively coined the term "shamanism" in 1951 and made it popular in academic and intellectual circles worldwide. Eliade saw in it the oldest form of the sacred , even the cross-cultural archetype of every occult tradition in general. [14] His cultural- philosophical approach is now considered very speculative and romanticizing. [39]

In the late 1960s, American writer Carlos Castañeda 's novel-like and alleged self-experiential accounts sparked enormous interest among a mass audience almost worldwide. The focus of his work was on the archaic technique of ecstasy pre-formulated by Eliade , which he stylized as a crucial feature of shamanic practices. [A3]

Around 1970, trance-induced spiritual practices became the subject of neurology for the first time, which dealt more closely with the altered states of consciousness of shamans and/or their healing successes. Endorphins ("happy hormones"), hypnosis - or placebo effects through drum and dance rituals were used as explanations. [40] Trance techniques include in question: "monastic seclusion with sensory deprivation ", fasting , sleep deprivation , litanies or repetitive verbal suggestions, dance with the side effect of hyperventilation, drugs such as Indian soma , Iranian haoma , Mongolian harmine , African iboga , Mexican mescaline , and psilocybin in Mexican peyote cactus (see peyote cactus cult ) , European henbane , fly agaric , hashish , alcohol, and East Asian opiates . [41]

In 1980, Michael Harner's concept of core shamanism as a worldwide universal primal religion was published. Many authors criticized such far-reaching generalizations and related their concepts only to the classic Siberian shamans; or they clearly distanced themselves from the predominance of spiritual aspects and examined cultural characteristics, social functions or the healing significance of necromancers in different cultures. [42]

Spiritual Shamanism Concepts: Origin, Popularity, and Criticism [ edit | edit source ]

"Shamanism = technique of ecstasy [in which the] soul leaves the body [of the shaman] for journeys into heaven and the underworld."

It was Eliade's extensive work that laid the foundation for all later theories of shamanism, in which the diverse forms of necromancy in different cultures were reduced to the religious-spiritual aspect and the techniques of ecstasy.

In the 1950s, the socio-critical Beat Generation literary movement opened the way for the study of spirituality and the use of hallucinogenic drugs in the western world . In this context are the autobiographical publications of the New York banker and private scholar R. Gordon Wasson in Life magazine on the use and effects of the psychotropic mushroom Mexican baldhead given to him by the Mazatec shaman María Sabinahad taught. Wasson tried to document the worldwide traditional use of mushroom drugs and described this phenomenon as a "religious moment". A veritable "mushroom pilgrimage tourism" to Mexico then developed; among them were well-known musicians such as Mick Jagger , John Lennon and Bob Dylan .

In the 1960s, the young, educated post-war generation massively criticized the increasing technocratization, commercialization, anonymization and rationalization of society, which was accompanied by a demystification of the world. Against this background, the so-called counter -cultures emerged , which primarily emerged in the hippie movement as a "psychedelic revolution" with an interest in Far Eastern and Indian religions or shamanic soul journeys and the consumption of mind-expanding drugs (from mushrooms to marijuana to mescaline and LSD) became an important part of the new quest for transcending life. There was also growing interest in spiritual practices in science: the psychologist Abraham Maslow , as the founder of humanistic psychology , formulated the "theory of self-realization", in which spiritual striving is at the forefront of human needs. On this basis, transpersonal psychology emerged as a subdiscipline , which postulated a great therapeutic benefit of this striving. [A4]

The book Altered States of Consciousness ( ASC for short ) by psychologist Charles Tart (1969) had a great influence on the conception of shamanism . He described the human potential for perception and cognition as going beyond the normal senses and rational reason. He named dreams, trance, drugs, meditation or hypnosis as access to such altered states of consciousness . This was the foundation of the Esalen Institute , founded in California with the participation of Alan Watts , Aldous Huxleyand Abraham Maslow was founded to convey alternative spirituality - including shamanic techniques - and to propagate their benefits for individual self-realization.

Julian Silverman, one of the leaders, conceived shamanism as a form of therapy as early as 1967, but the concept of Esalen student Michael Harner, who understood shamanism as a “technology for personal experiments and expansion of perception that is accessible to everyone”, achieved much greater recognition in the 1970s . Before that, however, the novelistic and autobiographical books of Carlos Castañeda - who had also taken courses at Esalen - from 1968 onwards ensured enormous popularity of the topic with a mass audience almost worldwide. Moreover, he was one of the pioneers of the new methodology of direct experience of shamanic practices by scholars transmitted directly by traditional indigenous people.However, this naturally had to lead to extremely subjective results that were difficult to verify and hardly stood up to the criteria of scientific work . Castañeda himself became the best example when it was proven in 1976 that his alleged teaching by the Yaqui shaman Don Juan Matus was simply invented. Nevertheless, the fascination with his work remained, which, as a modern myth, precisely and masterfully served the emotional and intellectual needs of society. [A5]

Even in the sciences, a number of other authors stuck to the concept of a universal “transcendent shamanism” despite the revelations about Castañeda's work and the criticism of Eliade's work, or used such theses as explanations for other phenomena. In addition, a number of other autobiographical ethnographies appeared, in which truth and fiction could no longer be separated from one another. These include the books by Hyemeyohsts Storm, Lynn Andrews, and Jeremy Narby , among others .

However, the concept of core shamanism (allegedly the "intersection" and the common "core" of all shamanic practices) by Michael Harner, which had far-reaching effects similar to those of Eliade's work, gained the most notoriety. Harner is also one of the autobiographical ethnographers. His career is the best example of the individual transformation from a scientifically working ethnologist to a practicing necromancer. The Foundation for Shamanic Studies founded by Harner has supported the development of esoteric neo-shamanismsignificantly influenced. Here, in various courses, a kind of "shamanism light" is conveyed to a broad audience, which (allegedly) does not require risky elements such as drug consumption or ecstatic trance. [A 6] At the same time, Harner's institute establishes various contacts between western esotericists and traditional shamans. In doing so, not only ethnographic reports are collected, but an active exchange takes place in both directions. As a result , the relatively well-preserved shamanism of the Tuvinians of southern Siberia is changing drastically: possibly in a direction that will soon no longer have anything in common with the original traditions of this people. [44]

Only in the last decade of the 20th century did some authors increasingly turn against the concepts of altered states of consciousness (ASC). The German ethnologist Klaus E. Müller cautiously writes: "Whether any 'reality' that is inaccessible to ordinary, so to speak 'roughly sensual' perception can be experienced [...] cannot be decided with ethnological means." [45] The French Ethnologist Roberte Hamayon, on the other hand, clearly rejects the thesis with the argument that altered states of consciousness cannot be empirically proven and often have no correspondence in the original descriptions of the indigenous people. [A7]

Widely accepted theses [ edit | edit source ]

Classical Siberian Shamanism or Animism [ edit | edit source ]

“[Siberian] shamanism is not just an archaic technique of ecstasy, not just an early development of religion, and not just a psychomental phenomenon, but a complex religious system. This system includes the belief that worships the helping spirits of shamans and the knowledge that guards the sacred texts (shaman chants, prayers, hymns and legends). It contains the rules that guide the shaman in acquiring the technique of ecstasy, and it requires knowledge of the objects used in the healing or divination seance. In general, all of these elements occur together.”

Research into the shamanic traditions began with the small Siberian peoples and at the beginning of the 21st century it often comes back to it: Many authors use the term shamanism exclusively for the Siberian cultural area, without naming it specifically; and although shamanism and religion are usually no longer placed in a primary connection, the classic Siberian form (often only called shamanism in an undifferentiated way) is often used as a synonym for the animistic religions of Siberia and Central Asia due to its extensive research history [3] [47].

The decisive factor for classical Siberian shamanism is the homologous (from one root) emergence of its varieties through the historical cultural transfer from one ethnic group to the next or - according to Michael Witzel - through migration movements of the ancient Asian peoples and their expansion across the Bering Strait . He points out that the range of a myth complex isolated by YE Berezkin (2005), described by Witzel as “Laurasian” and dated to the Late Paleolithic [48] largely coincides with the range of shamanism and the spread of the hypothetical Na-Dene language family and the C3 haplogroup of the Y chromosomecoincides.

Historical development [ edit | edit source ]

The presentation of the similarities between the beliefs , rites , cults and mythologies is hardly understandable without knowing the historical background of the peoples living there. Siberia was first settled around 20,000 to 25,000 years ago in the Upper Palaeolithic until the Neolithic when most of the entire area was inhabited. The first archaeologically verifiable places of worship emerged a few thousand years ago. They already show a pronounced cultural differentiation of the peoples there.

Peasant and shepherd peoples lived in the steppes and forest steppes of southern Siberia, while in the taiga to the north , hunting, fishing and gathering were the normal subsistence strategies . In particular, the peoples of Yakutia and the Baikal region had close ties to each other; archaeological artefacts such as rock paintings testify to this, which allow certain conclusions to be drawn about their religious ideas. The tundra and forest- tundra of the far north were predominantly small and relatively isolated peoples, either subsisting on sedentary fishing or hunting of marine mammals, or semi-nomadicwere reindeer herders .

Until the 16th and 17th centuries, the peoples of Siberia lived away from European influences. However, the beliefs there have been under the influence of various religions from the Near East, Central and East Asia for centuries. In addition to Zoroastrianism , Manichaeism and Christianity , these included above all influences from Buddhism . The Proto-Mongolian peoples had already come into contact with it from the 2nd century BC. Mongolian tribes then brought Mahayana Buddhism to Central Asia as far as the Amur region between the 8th and 12th centuries . At the beginning of the 15th century the Gelug was established in Tibetschool of classical Indian Buddhism and spread to Buryatia , Kalmykia and Tuva until the 17th century . Towards the end of the 19th century, Buddhism was established among the Transbaikal Buryats and influenced the everyday life, culture and outlook on life of many Siberian and Central Asian peoples. This led to a syncretic mixing of shamanic and Buddhist concepts. An example is the Buryat shaman mirror toli , originally from China, and the appearance of people who were both lamas and shamans. [49]

Cosmology [ edit | edit source ]

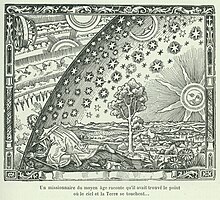

Part of the classic shamanic cosmology was the idea of the afterlife of a multi-layered cosmos of three (sometimes more) levels: in the upper and lower world there are benevolent and malevolent spirits and a world axis (axis mundi) connects the three levels in the center with each other. Depending on the culture, this axis is symbolized by the world tree, the smoke hole in the yurt, a holy mountain or the shaman's drum. The soul was viewed as an entity independent of the body , able to travel on this axis to the spirit world with the help of animal spirits. [A8]

The ritual ecstasy [ edit | edit source ]

The so-called "ritual ecstasy" was and is an essential element of classical shamanism, but also of all religious-spiritual shamanism concepts, some of which go far beyond Siberia. Depending on the illness of a patient, the wishes of a group member or the task of the community, the shaman embarked on a "soul journey into the world of spirits" in order to make contact with them there or to positively influence their work in terms of the problem to be solved. As a rule, the natural balance between the worlds was thought to be disturbed in some way and should be rebalanced in this way.

Such a necromancy ( séance ) was a highly ritualized affair that required various measures and had to take place at the right time in the right place (→ Kamlanie, the séance of the Siberian shamans in the article "Séance"). [10] [50] [51] [52]

The actual ecstasy is experienced as a transcendent experience, depending on the culture, either as one's own soul emerging or as being possessed by a spirit . [3]

Stepping out (also passive or trophotropic ecstasy ) - the classic and by far the most common type of ecstasy in Siberia - is described as a magical flight into another spaceless and timeless world, in which man and cosmos form a unit, so that answers and insights are revealed who would otherwise remain unreachable. The experience of this inner dimension is extremely real and highly conscious for the shaman. [53]

In the minds of traditional people, experiencing a journey to the afterlife corresponded to the dreams of ordinary people, albeit consciously induced and controlled; [52] similar to a lucid dream . The shaman's life functions sink to an abnormal minimum: shallow breathing, slow heartbeat, lower body temperature, rigid limbs and dulled senses characterize this state. [3]

In complete contrast to this is the ritual ecstasy of (learned) possession ( active or ergotropic ecstasy ), which in Siberia only occurs in a few ethnic groups in the transition areas to the high religions of Islam and Buddhism. In South and Southeast Asia or in Africa, however, such obsessions are the norm. The shaman has the feeling that a being from the other world is entering him and taking possession of his body for the duration of the ritual in order to solve the task. This leads to a sharp increase in bodily functions: he gets into an uproar, rages, foams, wriggles or "floats", speaks in incomprehensible languages and shows enormous strength. [3]

Both forms of ritual ecstasy result in altered perceptions that can affect all sensory impressions (sight, hearing, touch, smell, taste, bodily sensation). In addition, the emotions, the experience of meaning and the sense of time are modified. The intensity of these impressions is much stronger, more unpredictable and goes beyond the accumulated wealth of human experience than, for example, in the case of imaginary journeys that can be generated in the waking state. [54]

From a neuropsychological point of view, in both cases there is a certain form of an expanded state of consciousness , which is referred to as "ecstatic trance". In all forms of deep trance , there is at the same time a very deep relaxation as in deep sleep, the highest concentration as in awake consciousness and a particularly impressive pictorial experience as in a dream. The special way howthe shamans of Siberia (but also of Central Asia, northern North America, partly East and Southeast Asia and some peoples of the rest of America) bring about the trance, as well as the cultural imprint and the corresponding religious orientation, leads to the shamanic trance through the neurological "hyper- state of rest" to passive or through "hyper-arousal" to active ecstasy . [55]

The shaman always experiences this extraordinary mental state as a real event that seems to take place outside of his mind. Sometimes he sees himself from the outside (out of body experience ) similar to how near -death experiences are reported. As we know today, in this state people have direct access to the unconscious : the hallucinated spiritual beings arise from the instinctive archetypes of the human psyche; the ability to grasp connections intuitively – i.e. without rational thinking – is fully developed and is often expressed in visions that are later interpreted against one’s own religious background.

In order to achieve such states, certain formulas, ritual actions and mental techniques are used: These are, for example, the burning of incense, certain monotonous rhythms on special ceremonial drums or with rattles, dance ( trance dance ), singing or special breathing techniques. The Siberian shamans do not usually need psychedelic drugs to reach ecstasy like many other peoples. Only among the Uralic peoples is the fly agaric used from time to time (for some authors, the ability to trance without drugs is a characteristic of classical shamanism).

Particularly important for achieving a non-drug-induced trance is adopting ritual postures (according to Felicitas Goodman ) in connection with steady percussion rhythms in the range of 3.5 to 4.4 Hertz (equivalent to about 210 to 230 drumbeats per minute). [54] These frequencies correspond to theta and delta brainwaves otherwise typical of sleep or meditation. During the trance, so-called “paradoxical states of excitement” (paradoxical arousal) occur. Paradoxical because on the one hand they indicate a state that can be described as "more awake than awake" and at the same time EEG- Show curves that are otherwise only known from deep sleep stages. Subjects reported particularly impressive hallucinations during these trance phases. In addition, significant beta and delta increases are measured, which indicate a very deep relaxation and u. promote physical healing reactions and memory processes. The paradoxical states of excitement discovered by Giselher Guttmann in 1990 indicate a "relaxed high tension". In general, the release of a special combination of different endogenous neurotransmitters is stimulated, which "opens" consciousness: Perception is aimed entirely at inner content ( intersensory coordination), the cognitive filters of the normal waking state are inactive, while the observing ego remains active.

In principle, all ritual trances produce either particularly passive or particularly active physiological effects, which are then expressed by the shaman in the two aforementioned forms of ecstasy. However, the more intense the respective ecstasy, the less controllable the intentionally induced hallucinations can be. [56] [50] [51] [10] [57]

The measurement of brainwaves and similar methods can only prove that the consciousness works in a certain way. However, no conclusions can be drawn about the specific content of the respective states of arousal. Therefore, it is in principle impossible to prove or disprove that the impressions in ritual ecstasy are imaginary or actual glimpses of an afterlife. This remains a matter of faith. [54]

Müller: Elemental, Complex and Possession Shamanism [ edit | edit source ]

For a concrete description of the current situation and references see: Modern shamans in the light of history in the article "Shaman"

Apart from all secondary additions, shamanism at its core represents a visibly very old and optimally adapted to the conditions of existence of wild and field predatory cultures, i.e. apparently 'proven' and to that extent stable over long periods of time, as coherent as it is in itself 'unified' theory of being and nature ."

In 1997, the German ethnologist Klaus E. Müller presented an approach that describes shamanism as a kind of " science of magical-mythical thinking " that was developed, mediated and preserved by "appointed experts" with important social obligations. [58] Although Müller recognizes the similarities in terms of religious views or ritual trance techniques, he expressly distances himself from considering such " spiritual and occult aspects" as determining characteristics. [45]

Müller continues Adolf E. Jensen's thoughts, who understood shamanism as a typical phenomenon for hunter cultures, which regarded animals as their relatives in principle. [59] Clear indications of this assumption are the diverse totemic references to animals : the shamans were summoned by the “animal mother” in the spirit world or the “lord of the animals” , the helping spirits were predominantly animal-shaped, and the shaman—often dressed in animal attributes—transformed often on the journey into a spirit animal, the magic drum or mallet was taken as a symbolic mount for the journey and some more.

According to Müller, the original form of shamanism is above all a ritual for forgiveness and averting punishment and harm when a hunter disregards the traditional appeasement and binding rituals for killing an animal. This played a central role in everyday life for all hunters and ultimately served to secure animal and plant populations. [60]

In his opinion, shamanism arose somewhere in Asia in the Upper Paleolithic well before 4000 BC. Chr. and has spread from there in many centuries among the "soul mates" hunter peoples over the entire Asian continent and beyond to North, Central and South America as well as to Australia. [61] On the basis of the description of the shaman as "expert and mediator to the spirit world" and the resulting social obligations, a corresponding distribution map of shamanism can be created.

According to Müller, the "classical" area includes not only Siberia, but also today's Kazakhstan and scattered local communities in Southeast Asia, including the Indonesian islands. Sometimes he also mentions the shamanism of the Eskimo peoples of North America in this context. However, it is not clear whether he actually includes them in classical shamanism or not. According to Müller, the forms of shamanism of the Aborigines and the Indian peoples split off from the classic elementary forms at an early stage and continued to develop in isolation. [62]In contrast, for Witzel, Siberian shamanism is a relatively "recent" spin-off (at least 20,000 years old) from a more widespread paleo-shamanism . [63]

Müller considers it probable that the original (“elementary”) shamanism of the hunter-gatherers in the sub- polar regions of Asia and North America has survived largely unchanged up to the modern age, because the environmental and living conditions there have remained almost the same. [64] Moreover, he notes that to this day it is mainly found among ethnic groups that have a close relationship with the animal world (hunting and pastoral cultures as well as the horticultural and shifting field farmers of Amazonia, whose way of life has a strong "hunter's" component) . In pure planter cultures or among agropastoralists , shamanism has always played only a marginal role. [65]

Klaus E. Müller therefore derives his forms of shamanism primarily from their socio-economic foundations [66] and from this developed a three-part classification model (whose following descriptions are written in the past tense, as they only apply to a few isolated peoples now and then ): [67 ]

Elemental Shamanism [ edit | edit source ]

Color Scheme:

- Genesis:

- ( Primary ) elemental shamanism was typical of pure hunter cultures or of ethnic groups in which hunting played a prominent cultural role.

- Characteristics:

- The social base is based on egalitarian local communities or kinship groups ( lineages , clans ). The ethnic religions tended to be animistic . The shaman was predominantly male. He believes he is called by animal spirits and was primarily responsible for the success of the hunt or the observance of "hunting ethics ", but also acted as a healer and oversaw the reproductive success of the group. The ritual was not very pronounced and costumes or special aids were rarely used or only sporadically and in a simple form.

- distribution

- 1. Classic Asian cultural area

- Unique shape:

- Original nomadic to sedentary hunters, fishermen and gatherers of northern and eastern Siberia; since Russification often reindeer herders like the other Siberian peoples. Variants from historical differentiation:

- Paleo-Siberian (primary) foragers ( Chukchi , Yukagir , Koryak , Itelmen )

- Siberian (secondary) foragers ( Nganasanen , Dolganen , Keten )

- In north-eastern India in a few groups (attenuated), especially in the central area (e.g. Birhor ), scattered hunter-gatherers of Southeast Asia ( Derung , Yao , Akha , Mani , Orang-Asli peoples, Sentinelese , Shompen , Mentawai , Kubu , Penan , Batak , Aeta )

- 2. America and Australia

- Unique (classic?) form:

- Nomadic to sedentary hunters and gatherers of the Arctic North America ( Eskimos and Aleutians )

- Unique shape:

- Nomadic to semi-sedentary hunter-gatherers of the subarctic ( Athabasque , Algonquian ) and sedentary fishermen of the northwest coast

- Restricted form:

- Nomadic to sedentary hunters and gatherers (partly farmers) of the " Wild West " ( Plains Indians and Indians of the Plateau , Great Basin and California cultural areas )

- Nomadic hunters and gatherers of South America from the South American cultural areas of Llanos, Paraná and Tierra del Fuego

- Variable shape, not consistent:

- Nomadic Aboriginal hunter-gatherers , not consistent (mainly in the Western Desert and Northern Australia)

Complex Shamanism [ edit | edit source ]

Color Scheme:

- Genesis:

- The secondary complex shamanism arose among pastoral peoples and field farmers with a significant share of wild predators in Asia and America, presumably through diverse influences from neighboring agricultural societies and through contact with other religions - according to Witzel through the substitution of animal deities by plant and vegetation gods (e.g. corn gods like Cinteotl .)

- Characteristics:

- The social basis is formed by kinship groups, tribal societies or autonomous village communities . The animistic religions were more complex (e.g. with ancestor worship , sacrifice and a complicated cosmology). The calling of the shamans was based on ancestral spirits or the dead souls of earlier shamans (the latter mainly among Tungus and groups in the Altai-Mountains), or the status of shaman was inherited from father to son or from mother to daughter. There were predominantly male shamans, although there were also more female shamans. The functions and techniques of the shaman corresponded on the one hand to elementary shamanism, but there were also priestly, communal and domestic-family functions (e.g. at births, naming, burials, initiations). Rites, costumes with extensive accessories (e.g. made of metal) and utensils were often complex and of great importance. Entheogenic drugs were also often used to achieve trance .

- Distribution:

- 1. Classic Asian cultural area

- pastoral nomads . Variants from historical differentiation:

- 2. America

- Differentiated forms, e.g. T. not consistent:

- North America's Northeast , (e.g. Shawnee , Iroquois , Sauk , Powhatan )

- Mexico (e.g. Tarahumara , Huichol )

- Meso and South America (all planter societies outside the high Andes)

Possession Shamanism [ edit | edit source ]

Color Scheme:

- Genesis:

- The highly cultural and syncretic over-influenced possession shamanism can be traced back to the influences of archaic high cultures , the Asian high religions (particularly Buddhism ) and to the merging with possession cults.

- Characteristics:

- The usual social base was the peasant village community . The religious orientation consisted of an official direction - such as Islam , Lamaism , Vajrayana Buddhism, Hinduism , Shintoism , etc. - and a syncretic popular belief, the elements of the high religions andof ancient beliefs fused together. Women who felt called to do so were more often shamans than men. They felt a lifelong commitment to a spirit power or deity who was regularly sacrificed and worshiped in small, purpose-built temples. The tasks of the shaman corresponded to those of complex shamanism and were primarily aimed at medical services as well as counseling and divination. In contrast to the other forms of shamanism, there was no "journey to the hereafter" by means of a ritual ecstasy, but the shaman had the impression during the trance that her personal partner spirit was taking possession of her; “Enter” them and heal yourself, prophesy, etc. In contrast to others – not according to Müller-shamanistic - possession cults of other cultures (e.g. Africa or New Guinea), the entrance of the spirit took place at the invitation of the shaman and not "ambush-like" or against the will of the person concerned.

In the Islamic contact area, the influence of the old religions is much less recognizable today than in the Buddhist contact area. [68]

- distribution

- Asian cultural space

- Especially in sedentary rural communities

- Islamic sphere of influence (e.g. Uzbeks , Tajiks , Kyrgyz , Uyghurs )

- Lamaist sphere of influence (e.g. Buryats , Mongols , Yugur , Tibetans , Changpa , partly Nepalese )

- Buddhist-Daoist sphere of influence (e.g. majority populations of Japan , Korea , Taiwan , Central India )

Criticism [ edit | edit source ]

Although Müller includes various cultural aspects in his approach and his "three-type model" certainly makes differentiations, his "standardization" also sometimes leads to questionable results due to the global scale. For example, René Tecklenburg states that the shamanism of the Lakota Indians cannot simply be assigned to elemental shamanism, since it also has clear characteristics of the peasant type (close connection to the guardian spirit, numerous cult objects, complex ceremonies and rituals, sacrifices, etc.). [69]

Holistic Medicine [ edit | edit source ]

Modern theses often focus on a certain area of shamanism in a reductionist manner: for example on the psychological or neurobiological aspects or on medicine, although the cultural background is ignored.

Today, shamanism is often only understood as a special form of traditional healing methods. Ronald Hitzler , Peter Gross and Anne Honer , for example, describe it as "a complex, integrative social art that embeds the ability to heal, in the medical sense, in the concern for and in the service of the existential 'salvation' of fellow human beings in general." They attest gives the shamanic healing rituals a holistic approach that no longer exists in modern medicine. Instead of impersonal "repair services for the treatment object" by doctors, who no longer understand much about health but all the more about illness, shamanism is characterized by empathy, two-way communication and caring that goes beyond the well-being of the patient and even has the weal and woe of the entire community in mind. For Hitzler, Gross and Honer, shamanism is also "a way of man's universal-historical efforts to gain mastery of the seemingly unfathomable powers within him through knowledge." [70]

general criticism; controversial and speculative theses [ edit | edit source ]

(See also: Dead ends of ethnological research on religion )

"What is described in these writings [Eliades, Harners, etc.] as a shaman or as a shamanic event has little more in common than the word with what is to be understood as shamanism among the Chukchi, Tungus and Buriats in Siberia."

A fundamental criticism of all concepts of shamanism arises from the fact that all scientific approaches were written from a Eurocentric perspective and do not correspond directly to the magical-mythical thinking of traditional indigenous people: [72] Neither can the basic Western assumption of a separation into a natural-material and a supernatural-transcendent world , yet in nature and culture readily transferred to non-Western worldviews. [A9]

In addition, above all those theses are criticized that have torn ancient, grown traditions from their cultural and historical context and constructed a "new truth" from them, which have more the character of an ideology than a model thesis . Already the word component "-ism" suggests an apparently independent, systematic religion: In fact, however, it is "a complex of different religious ideas and ritual actions that are connected with the person of the shaman." [73] and selected by western authors , interpreted and rearranged. [22]One of the main problems of cross-cultural comparison of shamanic phenomena lies in the oral transmission of knowledge by individuals and a total lack of doctrine ; this "power of the shamans" leads to an enormously changeable diversity that must counteract any scientific approach. When community development and the maintenance of shamanic power require it, new elements - such as biomedical knowledge, Christian beliefs, or "new spirits" - are simply incorporated, and have been for centuries. [22]

The more an author generalizes and abstracts , the more he relies on circumstantial evidence and unprovable assumptions, or the more unconventional his approach, the greater the criticism his theses will provoke. There are some shamanic theories to which these statements apply. The extensive ethnographic records of Russian researchers of the 19th century already provide examples of this: The ethnographer Shoqan Walikhanov , for exampleso fascinated by the idea of a cross-cultural Siberian shamanism that he equated the (sacrificial) priests of the Islamic Kazakhs (Baqsi) and Kyrgyz (Baxši) with the Siberian shamans. Walikhanov did not recognize (or ignored) that there were a number of other magicians and healers in both cultures and that the Bagsi/Baxši must be described very differently on closer inspection. [74] Especially with the unifying ethnological theories of the 19th century, which are not used today or no longer in their original "scope" (like animism , fetishism , totemism , primitive peoples , racial studiesetc.), such “scientific wishful thinking” was widespread.

There are also enough recent examples where scientists have deliberately mixed or obscured fiction and reality to popularize their concept (→ Spiritual Shamanism Concepts: Origin, Popularity and Criticism ) . Against this background, the (unscientific) neo-shamanism should also be seen, whose authors use many shamanism concepts arbitrarily and in good faith, often uncritically mixing parts of this and that thesis and in this way creating fictitious constructs of thought that were not previously "based on stood on solid foundations". [75] [76]

Controversial theses [ edit | edit source ]

The approaches that go beyond the scientifically proven geographical and historical distribution area of North and Central Asian shamanism are often criticized.

Prehistoric Shamanism [ edit | edit source ]

In the English-language literature, the term prehistoric shamanism is sometimes used to denote those theses that postulate a prehistoric shamanism based on archaeological artifacts that are reminiscent of recent phenomena of shamanic practices . [77]

Although many finds are obviously reminiscent of shamanic rituals - such as the bird and the bird's beak of humans in the famous Lascaux cave painting and the way the bison was killed on its "life line" from anus to penis [78] - other interpretations are also possible in principle . It is undisputed that early man expressed religious ideas artistically, but what exactly this is about will always remain a mystery due to the fragmentary finds and the lack of contextual information. [79] Even the recent, much noted and appreciated conclusions of the South African archaeologist David Lewis-Williams and the French archaeologist Jean Clottesremain speculative and unprovable in many respects. [80]

Relation to Sufism [ edit | edit source ]

As numerous, primarily Soviet or Russian researchers show in the anthology "Shamanism and Islam" [81] , there is a close relationship between Central Asian/Siberian shamanism and Sufism . This is characterized by the adoption of numerous religious practices, such as the healing ritual or the meditative exercise dhikr in Sufism. The basic features of the belief in spirits in the form of the veneration of saints are also adopted.

Speculative theses [ edit | edit source ]

The concepts of shamanism, which select certain phenomena across cultures and use them to construct far-reaching models with universal claims, are today viewed as too speculative and are therefore hardly recognized – at least in terms of their core theses.

Shamanism as an archaic technique of ecstasy [ edit | edit source ]

"Il n'existe pas des zones géographiques privilégiées où la trance chamanique soit un phenomène spontané et organique: au rencontre des chamans un peu partout dans le monde ..."

This quote from the Romanian religious scholar Mircea Eliade reflects his central thought: "There is no specific geographical space (of shamanism), because the shamanic trance is a spontaneous and organic phenomenon that is found in all shamans in the world."

From his extensive cross-cultural research in Russian and Finnish ethnographies, he created an ideal type of shaman. He conceived shamanism as the world-wide primal phenomenon of human religiosity and raised the (passive) ecstatic trance with the "soul flight into the spirit world" to the central characteristic of all shamanic phenomena. In addition, he considered the classic Siberian cosmology to be a universal that is covered by foreign influences in many cultures. Eliade also clearly emphasized that a mystical-sacral condition that enabled direct contact with the divine was characteristic of prehistoric people and of today's "primitive people".

With his work Shamanism and Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy (first edition in French 1957), Eliade triggered enthusiasm in intellectual circles when it was published in the USA in 1964 for a topic that until then had only marginally interested religious scholars. This was not only due to the content of his studies, but at least as much to the unusual approach: Eliade brought together the ethnological, philosophical, religious studies and psychological perspectives in a synthesis of empirical analysis and imaginative philosophy of religion. For a long time, his thesis was considered the standard work on shamanism. It was instrumental in rehabilitating spiritual practitioners who until then had been viewed as insane or charlatans.

Since the 1990s, however, it has been increasingly frowned upon in ethnology. Art historians, literary scholars as well as neo-shamanistic and popular science authors still refer to Eliade, although the points of criticism largely dismantle his thesis. [82]

Criticism [ edit | edit source ]

Since Eliade wanted to concentrate entirely on his holistic religious-scientific approach, he refrained from examining the historical and political context of the phenomena more closely. Instead, he set up comparison criteria that can be described as "result-based" instead of "open-ended". In this way he also missed the aforementioned errors in the old ethnographic records from Russia. [74] In search of the deeper meaning , he mixed religious with mythical-literary phenomena and put the “ creative before the empiricalMoment". He assumed that the "sacred character" does not reveal itself with the help of the reductionist methods of various disciplines (physiology, psychology, linguistics, art, etc.), but only in its "own religious modality". His thesis is not purely academic, but a metaphysical interpretation of history and the world. He explained contradictions and deviations by “decadence” and “contamination” by other cultures and religions.

Eliade idealized and romanticized the "archaic spirituality" and "primitive cultures" in the Eurocentric tradition of Herder and Boaz. Instead of approaching the actual ethnic mentalities, some authors recognize more Christian motives in him: The mystical original state corresponds to paradise, the historical civilization process to the fall of man and the shamanic soul journey was supposedly originally a "heavenly journey" to the upper world according to Eliade.

Until the 1990s, his approach led to sharp debates about his methodology, but also about the reductionism in religious studies. From the point of view of anthropology, Eliade's method is criticized above all because it is more rooted in his role as a shamanic prophet than in serious scientific work. Various authors complain that he simply ignored historical, anthropological, sociological and economic perspectives, making his representations unverifiablebe. In addition, he is accused of going beyond the mere attempt at explanation and of legitimizing unscientific neo-shamanism with the statement "that the mystical original state can be visualized by anyone at any time with the help of shamanic ecstasy". [83] [82] Klaus E. Müller described Eliade's theses as "very speculative in terms of content". [84]

See also [ Edit | edit source ]

![]() Topic lists: Religious ethnology + ethnomedicine - overviews in the portal: ethnology

Topic lists: Religious ethnology + ethnomedicine - overviews in the portal: ethnology

- Mongolian shamanism

- Shamanism in Korea

- Shamanism in Japan

- Wuism (former classical shamanism of China)

- Animalism (religious attachment to animated animals)

- Animatism (sees inanimate things in nature as alive)

- fetishism (religion)

- Archaic Spirituality in Systematized Religions

Literature [ edit | edit source ]

- Hans Peter Duerr : Sedna or The Love of Life. (Suhrkamp paperback), 2nd edition, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1989, ISBN 978-3-51838-210-3

- Mircea Eliade : History of Religious Ideas. 4 volumes. Herder, Freiburg 1978, ISBN 3-451-05274-1 .

- Mircea Eliade: Shamanism and Archaic Ecstasy Technique. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 2001, ISBN 3-518-27726-X (original: 1951).

- Martin Gimm : The secret shamanism of the Qing emperors and the Tangzi shaman temple. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2018, ISBN 978-3-447-10962-8 .

- Valentina Gorbatcheva, Marina Federova: The Peoples of the Far North. Art and culture of Siberia. Parkstone Press, New York 2000, ISBN 1-85995-484-7 .

- Giselher Guttmann, Gerhard Langer (eds.): Consciousness. Multidimensional designs. Springer, Vienna/New York 1992, ISBN 3-211-82361-1 .

- Michael Harner: Hallucinogens and Shamanism. Oxford University Press, New York 1973.

- Helmut Hoffmann : Symbolism of the Tibetan religion and shamanism. Stuttgart 1967.

- Mihály Hoppál: The Book of Shamans. Europe and Asia. Econ Ullstein List, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-550-07557-X .

- Åke Hultkrantz , Michael Rípinsky-Naxon, Christer Lindberg: The Book of Shamans. North and South America. Munich 2002, ISBN 3-550-07558-8 .

- Adolf Ellegard Jensen: Myth and cult among primitive peoples - religious studies considerations. dtv, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-423-04567-1 (original: 1951).

- Hans Läng : Cultural history of the Indians of North America. Gondrome, Bindlach 1993, ISBN 3-8112-1056-4 .

- David Lewis-Williams: The Mind in the Cave. Consciousness and the Origins of Art. Thames & Hudson, London 2004, ISBN 0-500-28465-2 .

- Klaus E. Müller: Shamanism. Healers, spirits, rituals. 4th edition. Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-41872-3 (original: 1997).

- Dirk Schlottmann : Korean shamanism in the new millennium. Peter Lang, Frankfurt/Bern 2007, ISBN 978-3-631-56856-9 (European university publications; folklore/ethnology).

- Monika and Udo Tworuschka: Religions of the World. In history and present. Bassermann, Munich 1992/2000, ISBN 3-8094-5005-7 .

- Karl R. Wernhart: Ethnic Religions - Universal Elements of Religious. Topos, Kevelaer 2004, ISBN 3-7867-8545-7 , p. 134.

Web Links [ Edit | edit source ]

- Literature by and about shamanism in the catalog of the German National Library

- Audio from WDR 5 Signs of Life: Global Balance: Shamanic Crisis Management. August 23, 2020 (28:58 minutes; online congress from the Institute for Holistic Medicine in May 2020; available until August 21, 2021 ).

Notes [ Edit | edit source ]

- ↑ This definition of terms forms the lowest common denominator of various current definitions from the period after 1990.

Itemizations [ Edit | edit source ]

- ↑ Gorbatcheva, p. 181.

- ↑ Mihály Hoppál: The Book of Shamans. Europe and Asia. Econ Ullstein List, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-550-07557-X , p. 11 ff.

- ↑a b c d e f g László Vajda, Thomas O. Höllmann (eds.): Ethnologica. Selected essays. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 1999, ISBN 3-447-04209-5 , pp. 145-147.

- ↑ Viviana Korn: Shamanism . In: “Brief information on religion” from the Religious Studies Media and Information Service e. V., Marburg 2010, retrieved on January 30, 2015.

- ↑ Manfred Kremser: In the beginning was the ritual - Schematic constellation work in indigenous cultures? In: Guni Leila Baxa, Christine Essen, Astrid Habiba Kreszmeier (ed.): Embodiments: Systemic constellation, body work and ritual. Online edition, Auer Verlag, Heidelberg 2002, ISBN 3-89670-718-3 , pp. 110–128.

- ↑ Karl R. Wernhart: Ethnic religions - universal elements of the religious. Topos, Kevelaer 2004, ISBN 3-7867-8545-7 , p. 139.

- ↑a b Piers Vitebsky: Shamanism. Taschen, Cologne 2001, p. 11.

- ↑ Roger N Walsh, The spirit of shamanism. Tarcher, New York 1990, p. 11.

- ↑ Roger N. Walsh in Gerhard Mayer: Shamanism in Germany. Concepts - Practices - Experiences. Volume 2 of Crossing Boundaries. Contributions to the scientific study of extraordinary experiences and phenomena. Ergon, Würzburg 2003, ISBN 3-89913-306-4 , p. 14.

- ↑a b c d e Dirk Schlottmann: What is a shaman? Korean Shamanism Today. ( Memento of June 6, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) In: journal-ethnologie.de, Current Issues 2007, Museum der Weltkulturen, Frankfurt 2008, retrieved on June 5, 2018 (web.archive.org).

- ↑a b Ronald Hutton: Shamans. Siberian Spirituality and the Western Imagination. University of Michigan, Hambledon / London 2001, ISBN 1-85285-324-7 , p. VII.

- ↑a b Klaus Sagaster: Shamanism, published in: Horst Balz, James K. Cameron, Stuart G. Hall, Brian L. Hebblethwaite, Wolfgang Janke, Hans-Joachim Klimkeit, Joachim Mehlhausen, Knut Schäferdiek, Henning Schröer, Gottfried Seebaß, Hermann Spieckermann , Günter Stemberger, Konrad Stock (eds.): Theological Real Encyclopedia , Volume 30: "Samuel - Soul". Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, New York 1999, ISBN 3-11-019098-2 , pp. 72–76.

- ↑a b c Thomas O. Höllmann, Götzfried and Claudius Müller (eds.): Ethnologica: Selected essays by László Vajda. Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1999, ISBN 3-447-04209-5 , pp. 145–147.

- ↑a b c d Kai Funkschmidt: Shamanism and Neo-Shamanism . In: Evangelical Central Office for World View Questions ezw-berlin.de, Berlin, 2012, retrieved on February 4, 2015.

- ↑a b Andreas M. Oberheim: Shamanism in South America . ( Memento from June 10, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Annika Wieckhorst, Proseminar: Introduction to Medical Anthropology. University of Cologne, summer semester 2007, retrieved on February 18, 2015.

- ↑ Waldemar Stöhr: Lexicon of peoples and cultures. Westermann, Braunschweig 1972, ISBN 3-499-16160-5 , p. 59.

- ↑ Michael Witzel: The Origins of the World's Mythologies. Oxford University Press, New York 2011, p. 382 ff.

- ↑ Mariko Namba Walter, EJ Neumann Fridman (eds.): Introduction to Shamanism. Santa Barbara 2004, p. XVII ff.

- ↑ Walter Hirschberg (founder), Wolfgang Müller (editor): Dictionary of Ethnology. New edition, 2nd edition. Reimer, Berlin 2005, pp. 326–327.

- ↑ Witzel 2011, p. 132 ff.

- ↑ Heiko Grünwedel (possibly ed.): Shamanism between Siberia and Germany: Cultural exchange processes in global religious discourse fields. transcript, Bielefeld 2013, ISBN 978-3-8376-2046-7 , p. 46.

- ↑a b c Michael Kleinod: Shamanism and Globalization. Essay as part of the seminar on cultural globalization and localization, ethnology, University of Trier 2005, ISBN, pp. 4-7.

- ↑ Karl R. Wernhart: Ethnic religions, published in: Johann Figl (ed.): Handbook of religious studies: Religions and their central themes. Verlagsanstalt Tyrolia, Innsbruck 2003, ISBN 3-7022-2508-0 , pp. 278-279.

- ^ Juha Janhunen , Siberian shamanistic terminology, Suomalais-ugrilaisen Seuran toimituksia/ Memoires de la Societe finno-ougrienne, 194, 1986, pp. 97-98.

- ↑ Hoppál, p. 11 ff.

- ↑ Marvin Harris: Cultural Anthropology - A Textbook. From the American by Sylvia M. Schomburg-Scherff, Campus, Frankfurt/New York 1989, ISBN 3-593-33976-5 , p. 285.

- ↑ Alexandra Rosenbohm (ed.): Shamans between myth and modernity. Militzke, Leipzig 1999, ISBN 3-86189-159-X , p. 7.

- ↑ Florian Deltgen: Controlled Ecstasy: The hallucinogenic drug Cají of the Yebámasa Indians. Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 1993, ISBN 3-515-05630-0 , p. 27.

- ↑ Roberte Hamayon: Shamanism and the hunters of the Siberian forest: soul, life force, spirit. In: Graham Harvey: The Handbook of Contemporary Animism. Acumen Publishing, 2013, ISBN 978-1-84465-712-4 , p. 284.

- ↑ Michael Lütge: Heaven as the home of the soul. Visionary ascension practices and constructs of divine worlds in shamans, magicians, Anabaptists and Sethians. University of Marburg, Ms. 2008 online (PDF; 13.1 MB), p. 29 f.

- ↑ Ulrich Berner: Mircea Eliade. In: Axel Michaels (ed.): Classics of religious studies. Munich 1997, p. 352 f.

- ↑ Klaus E. Müller, p. 104.

- ↑ Klaus E. Müller, pp. 104-105.

- ↑ Klaus E. Müller, pp. 107-108.

- ↑ SM Shirokogoroff: Psychomental Complex of the Tungus. Kegan, Paul, Trench, Trubner; London 1935.

- ↑ Klaus E. Müller, p. 109.

- ↑ Claude Lévi-Strauss: Structural Anthropologie I. Frankfurt am Main 1967, p. 187.

- ↑ Klaus E. Müller, pp. 110-111.

- ↑ Wolfgang Saur: Mircea Eliade today. In: Secession. No. 16, February 2007. ISSN 1611-5910 .

- ↑ Raymond Prince: The Endorphins and: Shamans and Endorphins . ethos. Journal of the Society for Psychological Anthropology 10(4): 303-316; 409-423 (1982).

- ↑ M. Lütge: Heaven as home , 2008, p. 35.

- ↑ Klaus E. Müller, pp. 8-9, 19-20.

- ↑ Mircea Eliade, quoted in: Riedl, p. 93.

- ↑ Anett C. Oelschlägel : Plural world interpretations. The example of the Tyva of southern Siberia. SEC Publications, Fürstenberg/Havel 2013, ISBN 978-3-942883-13-9 , pp. 31, 60 f.

- ↑a b c Klaus E. Müller, p. 119.

- ↑ Mihály Hoppál: Shamans and Shamanism. Pattloch, Augsburg 1994, ISBN 3-629-00646-9 , p. 32 f.

- ↑ Gorbatcheva, p. 181.

- ↑ Witzel 2011, p. 39.

- ↑ Erich box (ethnologist) (ed.): Shamans of Siberia. Magician - Mediator - Healer. On the exhibition at the Linden-Museum Stuttgart, December 13, 2008 to June 28, 2009, Reimer Verlag 2009, ISBN 978-3-496-02812-3 , pp. 164-167.

- ↑a b Manfred Kremser: Ethnological research on religion and consciousness. Lecture notes from the University of Vienna, summer semester 2001, pp. 14–15. pdf version ( Memento of March 4, 2016 at the Internet Archive )

- ↑a b Bruno Illius: The idea of "detachable souls". In: The concept of the soul in religious studies. Johann Figl, Hans-Dieter Klein (eds.), Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2002, ISBN 3-8260-2377-3 , pp. 87–89.

- ↑a b Klaus E. Müller, p. 19.

- ↑ Dennis and Barbara Tedlock (eds.): Over the Rim of the Deep Canyon. Teachings of Indian Shamans. 8th edition. from the American by Jochen Eggert, original edition 1975, Diederichs, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-424-00577-0 , p. 170.

- ↑a b c Nana Nauwald, Felicitas D. Goodman & Friends: Ecstatic Trance. Ritual postures and ecstatic trance. 4th edition. , Binkey Kok, Haarlem (NL) 2010, ISBN 978-90-74597-81-4 , pp. 35, 43, 48, 59.

- ↑ Shamanism . In: praehistorische-archaeologie.de, retrieved on June 12, 2015.

- ↑ Andrea Marchhart with Elke Mesenholl-Strehler as supervisor: Trance experience and its influence on personality. Inter-University College for Health and Development, Graz (AU) 2008.

- ↑ Klaus E. Müller, p. 19.

- ↑ Klaus E. Müller, pp. 8-9, 12, 19-20, 113-114.

- ↑ Klaus E. Müller, pp. 17-18.

- ↑ Klaus E. Müller, pp. 115-117.

- ↑ Klaus E. Müller, p. 28.

- ↑ Klaus Müller, pp. 28-30.

- ↑ Witzel 2011, p. 382 ff.

- ↑ Klaus E. Müller, p. 117.

- ↑ Klaus E. Müller, p. 113.

- ↑ Klaus E. Müller, pp. 29-34.

- ↑ Klaus E. Müller, pp. 8-9, 19-20, 30-33, 71, 106, 115-119.

- ↑ Annegret Nippa (ed.): Little abc of nomadism. Publication accompanying the exhibition “Explosive Encounters. Nomads in a sedentary world”, Museum für Völkerkunde Hamburg, Hamburg 2011. P. 180-181.

- ↑ (ed.): The compressors. An anthropological study of Lakota shamanism. LIT Verlag, Zurich 2006, ISBN 3-8258-0362-7 , p. 210.

- ↑ Ronald Hitzler , Peter Gross , Anne Honer : Diagnostic and therapeutic competence in transition. In: Franz Wagner (ed.): Medicine: moments of change. Springer, Berlin et al. 1989, p. 165.

- ↑ Hartmut Zinser: Shamanism in the "New Age". In: Michael Pye, Renate Stegerhoff (eds.): Religion in a foreign culture. Religion as a minority in Europe and Asia. dadder, Saarbrücken 1987, ISBN 3-926406-11-9 , p. 175.

- ↑ Hans Peter Duerr (ed.): Longing for the origin: to Mircea Eliade. Syndikat, Frankfurt am Main 1983, ISBN 3-8108-0211-5 , p. 218.

- ↑ Evelin Haase: Mediator between humans and spirits - shamanism of the Solon (Ewenks) in North China. In: Claudius Müller (ed.): Ways of the gods and men. Religions in Traditional China. Edition, Reimer, Berlin 1989, p. 148.

- ↑a b Till Mostowlansky: Islam and Kyrgyz on Tour. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 2007, ISBN 978-3-447-05583-3 , pp. 42-48, 64-66, 76, 86-87.

- ↑ Hartmut Zinser : On the fascination of shamanism. In: Michael Kuper (ed.): Hungry ghosts and restless souls. Texts on shamanism research. Dietrich Reimer, Berlin 1991, pp. 17–26.

- ↑ Harald Motzki: Shamanism as a problem of religious-scientific terminology. Brill, Cologne 1977.

- ↑ William F. Romain, Shamans of the Lost World: A Cognitive Approach to the Prehistoric Religion of the Ohio Hopewell. Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham (US) 2009, ISBN 978-0-7591-1905-5 , pp. 3, 7, 17–18.

- ↑ Witzel 2011, p. 399 f.

- ↑ Linden Museum for Regional and Ethnology: Yearbook of the Linden Museum Stuttgart, Tribus. No. 52, 2003, Stuttgart, p. 261.

- ↑ Disenchanted Cave Painters . In: wissenschaft.de, July 20, 2004, retrieved on June 8, 2015.

- ↑ Thierry Zarcone, Prof. Angela Hobart (ed.): Shamanism and Islam: Sufism, Healing Rituals and Spirits in the Muslim World . IBTauris & Co Ltd, 2012, ISBN 978-1-84885-602-8 .

- ↑a b Riedl, pp. 91–98.

- ↑ Ulrich Berner in Axel Michaels (ed.): Classics of religious studies: from Friedrich Schleiermacher to Mircea Eliade. 3rd Edition. C. H. Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-61204-6 , pp. 343-353 esp. 348-351.

- ↑ Klaus E. Müller, p. 111.

A. Karin Riedl: Artist shamans. Appropriating the shaman concept with Jim Morrison and Joseph Beuys. transcript, Bielefeld 2014, ISBN 978-3-8376-2683-4 .