Quakers, Mennonites and Omish History

The Quakers, Mennonites and Omish

Although Professing Almost the Same Beliefs and Convictions, These Three Sects Are

Only Loosely ‘Related’ To Each Other

By R.C. Hall, Ph. D.

Submitted by Lesli Christian

(The Herald Advertiser, Nov. 6, 1938)

About a year ago, the Macmillan company of New York published a volume entitled “Children of Light” which, while prepared from a Quaker viewpoint and largely, perhaps, for the inspiration and encouragement of Quakers themselves and related sections, such as Mennonites, is very instructive and interesting to non-Quakers as well, and to all, perhaps, who are interested in the history both of their country and its religious development.

“Children of Light” is a volume of special importance also to those who wish to make a study of the particular sects of which it treats from a sort of investigational standpoint. That is, it bears the stamp of greater authority than the ordinary volume written by one individual and which is likely to reflect that individual’s own ideas and interpretations so as to give but a one-sided view of the subject as a whole. This volume, however, is not the work of one individual but of many. It was edited, it is true, by Howard H. Brinton, according to the information contained on its title page, but its table of contests shows that it contains 15 chapters, each written by a different author. Perhaps we can gain a better idea of just what the work proposes from the following paragraph from the introduction by its own editor:

Early Name For Quakers

“The essays in this book, although they cover a wide range of subjects, are not without inherent unity of a nature suggested by the title of the collection. “Children of the Light” was an early name for the Quakers, and these studies illustrate various ways and means by which the “Inner Light” was followed by its children. The order is approximately chronological, with similar subjects grouped together.”

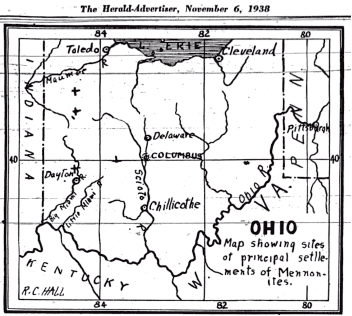

While Chapter VIII on the Mennonites and Chapter XII on the Quakers of the Old Northwest Territory are particularly interesting to students of Ohio Valley and so called Midwest history, the whole volume is a real contribution to religious literature in general. For no matter in what period or region one wishes to consider these sects, the essays of this volume furnish an excellent foundation for study.

“Children of Light” was prepared and published in honor of Rufus M. Jones on the occasion of his 75th birthday. Mr. Jones is referred to by Mr. Brinton in his introduction to the work as “one who has contributed more widely than any other person now living to knowledge and understanding of the history of the Society of Friends.” Further on, Mr. Brinton continues, “We who write this book are able to commemorate only one part of Rufus Jones’ many-sided life and scholarship. Our essays are strictly historical. But in honoring Rufus Jones as historian, we look up to him as more than a historian. His writings in Quaker history glow with a meaning which is of cosmic and ultimate significance.”

Author of 80 Volumes

Although the object of this review is not to give an account of the life of Mr. Jones, it may be well to mention that at the conclusion of the volume “Children of Light,” there is given a list of the books written by Rufus M. Jones from 1889 to 1937, and they number over 80 volumes which do not include a number of articles. These were published by such reputable publishers as the Macmillan Company, The Abington Press, Harper and Brothers and others. They cover a variety of subjects, mostly dealing with some phase of Quakerism.

To most people unacquainted with the real doctrine of the Friends, or Quakers, they perhaps mean little except a group of peculiar folks who refuse to bear arms, oppose the taking of oaths, talk with “these” and “thous” and dress in plain clothes. Of course, most people who have read anything at all of the history of the Quakers know that the sect was founded in England by George Fox and that, in America, William Penn was perhaps its greatest representative. And since it is from Penn’s branch of the sect that most of the present American branches perhaps spring either directly or indirectly, Americans should be particularly interested in what Penn believed, taught and practiced. Thus the first chapter in “Children of Light,” which is really in the nature of a criticism of one of Penn’s chief works, is of special interest. It is a discussion of William Penn’s “The Christian Quaker,” by Herbert G. Wood, and explains how Penn refutes the charges quite common in earlier days that Quakers were not Christians. It also explains the Quaker doctrine of the “Inner Light” or “The Light Within” and “Gentile Divinity,” all of which appear to mean in general that some people are guided into salvation by an inner light.

Would Be Saved

In other words, Penn taught that Gentiles, such people as Socrates and others who had never had the advantages of Christianity, would be saved by this inner knowledge and understanding. To quote Mr. Wood: “William Penn’s estimate of the extent and spiritual value of Gentile enlightenment is more generous and less cautious than Amyraut’s. He writes in the spirit of Justin Martyr, of whom Rendel Harris says, “When he saw Socrates struggling in the sea, he was not content merely to throw him a rope to assist his salvation, but he hauled him on board the ship of Christian faith and bade him make himself at home with the crew.” Like Justin Martyr, William Penn recognizes Christians before Christ. He was the more enthusiastic in his praise of Gentile divinity, because in some particulars Greek philosophers supported Quaker testimonies. Socrates’ refusal to take fees for teaching and his condemnation of the Sophists for moneymaking were in line with Friends’ distrust of a paid ministry, and Penn was glad to find pre-Christian sages who condemned swearing and maintained Friends’ testimony against oaths. Penn pointed the contrast on these differences between Gentile divinity and the practice of professing Christians so sharply that he lent some color to Keith’s charge that he recognized only pagans as fellow-Christians, and disowned all who profess and call themselves Christians other than Friends.”

This one paragraph, we believe, will suffice to show both Penn’s teaching on this subject and Wood’s apparently fair and unbiased criticism of it.