앙드레 지드

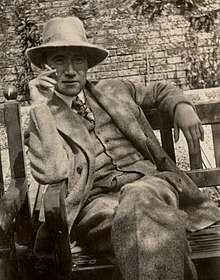

앙드레 지드의 1920년도 모습 | |

| 작가 정보 | |

| 출생 | 1869년 11월 22일 파리시 |

| 사망 | 1951년 2월 19일(81세) 파리 |

| 직업 | 소설가, 수필가 |

| 수상 | 노벨 문학상 1947년 |

| 영향 | |

| 영향 받은 인물 | 표도르 도스토옙스키, 헨리 필딩, 로제 마르탱 뒤 가르, 프리드리히 니체, 타고르, 오스카 와일드 |

| 영향 준 인물 | 자크 리비에르, 브라언 오놀란, 장 폴 사르트르, 알베르 카뮈, 유키오 미시마 |

서명 | |

앙드레 지드(Andre Paul Guillaume Gide, 1869년 11월 22일 ~ 1951년 2월 19일)는 프랑스의 소설가·비평가이다.

법학 교수의 아들로 파리에서 태어나 신경발작으로 인한 허약한 몸으로 학교를 중퇴하고, 19세부터 창작을 시작하여 1891년 데뷔작인 《앙드레 왈테르의 수기》를 발표하였다. 아프리카 여행에서 돌아와 《팔뤼드》, 《지상의 양식》, 《배덕자》 등을 발표하였으며, 그가 유일한 소설이라 부른 《사전꾼들》도 상징파의 궤도를 벗어나지 못하였다.

주요 작품은 1909년에 발표한 《좁은 문》, 《이자벨》, 《교황청의 지하도》 등이 있으며, 제1차 세계대전 후에는 《전원 교향악》, 《보리 한 알이 죽지 않으면》 등이 있다. 1927년에 발표한 《콩고 기행》은 비평가로서의 그를 높이 인정할 수 있는 작품이며, 소련을 여행한 후 쓴 《소련 기행》은 좌파 언론계의 공격을 받기도 하였다.

그는 일찍이 쇼펜하우어·데카르트·니체 등의 철학서와 문학서를 읽고, 로마 가톨릭 교회와 개신교의 영향을 받았다. 1947년 노벨 문학상을 받았다. 작품으로 《프레텍스트》, 《엥시당스》, 《지드의 일기》, 《상상적 면담기》, 《도스토옙스키론》 등이 있다.

작품

[편집]청교도

[편집]1869년 파리시에서 태어난 앙드레 지드는 20세기 초반 프랑스 문단을 대표하는 작가다. 초기에는 시인이 되려고 했으며 말년에는 희곡 작품을 집필하기도 했으나 중요한 작품은 대부분 소설이다. 표현 형식이 어떤 것이었건 작품 전체를 관통하는 주제는 기독교 이원론적 세계관과 관련된 도덕 윤리적 문제다. 프랑스 문학사상 거의 유일하게 개신교 신자, 그것도 종교개혁자 장 깔뱅의 사상에 근거하여 금욕과 절제를 주장한 청교도였던 앙드레 지드에게서 정신과 육체, 이성과 본능, 선과 악 등으로 세계를 이분하는 기독교이원론은 첨예한 갈등의 양상을 띠고 있었는데, 이분법적 사고에 내재되어 있는 정신과 이성을 우위에 두는 가치관이 문제가 되었다. 앙드레 지드는 이러한 가치관이 인간에게 부과하는 도덕의무가 육체와 본능을 가진 인간의 욕망을 억압하는 것이 부당하다는 점과 아울러 인간의 욕망을 인정하고 도덕가치를 부여해야 한다는 것을 주장했다.

삶을 충만하게 살라

[편집]법학 교수였던 아버지가 일찍 죽고 난 뒤 어머니의 엄격하고 철저한 청교도 교육 속에서 자랐던 허약하고 예민한 지드는 자신의 어린 시절을 행복하게 생각하지 않았다. 자신이 받은 교육이 남긴 것은 자기혐오와 죄의식뿐이었다고 자서전 앞머리에서 씁쓸하게 말하고 있다. 이러한 죄의식을 심화하게 된 결정적인 요인은 청년이 되면서 발견하게 된 동성애 성향이었다. 그러나 지드는 이것을 반전의 기회로 만든다. 자신의 가장 큰 고통의 근원을 오히려 긴 원죄의식에서 벗어나는 계기로 만들었던 것이다. 인간이 영혼과 육신으로 온전한 행복을 향유한다면 그것이 죄악일 수 있는가? 지드는 하나님이 인간에게 모든 희열을 향유하며 삶을 충만하게 살도록 허락했다고 믿는다. 그리고 그것을 설득한다. 그에 따르면 인간의 행복을 억압하는 것은 하나님이 아니라 인간 자신이 부과한 도덕과 윤리라는 것이다.

1893년에서 1894년까지 지드는 북아프리카를 여행하면서 자신이 동성애자라는 것을 받아들였다. 그는 파리에서 오스카 윌드와 친구가 되었고 1895년 그 둘은 알제에서 만났다. 윌드는 지드가 동성애자라는 느낌을 받아 그에게 말해주었는데 사실 지드는 이미 스스로 알고 있었다.

1901년 지드는 세인트 프레라드 만에 있는 마드리아 자산을 빌렸고 저지에 살면서 그 곳에 머물렀다. 1901~1907 이 기간은 그에게 혼란과 무관심의 시간이었다.

1908년 지드는 NFR(신프랑스주의)문학 잡지를 설립하는 것을 도왔다. 1916년 15살 밖에 되지 않았던 마크 알레그레는 그의 연인이 되었다. 마크는 엘리 알레그레의 5명의 아들 중 한 명이었다. 엘리 알레그레는 지드의 좋지 않은 성적때문에 이전에 지드 어머니에 의해 고용된 선생님이다. 후에 그와 지드는 친한 친구가 되었다 ; 알레그레는 지드의 결혼식에서 들러리였다.

1923년 그는 표도르 도스토옙스키 책을 출판했다 ; 하지만, 대중 판인 목동(1924)에 동성애를 옹호해서 많은 비난을 받았다. 후에 그는 이것을 그의 가장 중요한 업적으로 여겼다.

사회참여

[편집]그의 작품 활동과 사회 참여는 일체 억압으로부터 인간을 해방하고 개인적 자유를 회복시키기 위한 노력의 궤적이었다. 인간을 억압하는 엄격하고 경직된 윤리규율, 그 부당함에 침묵하는 소시민 사회의 위선과 순응, 창조성을 억압하는 아름다움에 대한 기준, 타민족 착취를 정당화하는 식민주의 등 당대 지식인들이 ‘시대의 대표자’라고 불렀던 지드가 이의를 제기하지 않았던 문제는 거의 없었다. 그가 하고자 했던 것은 진정성의 이름으로 기존 질서를 검토하고 새로운 질서를 수립하는 것이었다. 그의 위대함은 아마도 자신의 신념을 설득하기 위해 마지막 순간까지 지치지 않고 노력했다는 사실일 것이다. 1947년 옥스퍼드 대학교의 명예박사 학위와 1947년 작가 최고 영예인 노벨문학상 수상은 그러한 그의 용기와 노력에 대한 평가였다. 그리고 어떤 인정보다 더욱 명예로운 인정은 그의 주장이 모두 받아들여졌다는 사실일 것이다. 그가 주장했던 새로운 가치들은 사르트르와 카뮈 같은 다음 세대의 가치관이 되었다.

작품 목록

[편집]- Les cahiers d'André Walter – 1891

- Le traité du Narcisse – 1891

- Les poésies d'André Walter – 1892

- Le voyage d'Urien – 1893

- 사랑 La tentative amoureuse – 1893

- Paludes – 1895

- Réflexions sur quelques points de littérature – 1897

- 지상의 양식 Les nourritures terrestres – 1897 (translated as The Fruits of the Earth)

- Feuilles de route 1895–1896 – 1897

- El Hadj

- Le Prométhée mal enchaîné – 1899

- Philoctète – 1899

- Lettres à Angèle – 1900

- De l'influence en littérature – 1900

- Le roi Candaule – 1901

- Les limites de l'art – 1901

- 부도덕한 사람(배덕자) L'immoraliste – 1902 (translated by Richard Howard as The Immoralist)

- Saül – 1903

- De l'importance du public – 1903

- Prétextes – 1903

- Amyntas – 1906

- Le retour de l'enfant prodigue – 1907

- 도스토옙스키를 말하다 Dostoïevsky d'après sa correspondance – 1908

- 좁은 문 La porte étroite – 1909 (translated as Strait Is the Gate)

- 오스카 와일드 Oscar Wilde – 1910

- Nouveaux prétextes – 1911

- Charles-Louis-Philippe – 1911

- C. R. D. N. – 1911

- Isabelle – 1911

- Bethsabé – 1912

- Souvenirs de la Cour d'Assises – 1914

- 교황청의 지하실 Les caves du Vatican – 1914 (translated as Lafcadio's Adventures and The Vatican Cellars)

- La marche Turque – 1914

- 전원교향악 La symphonie pastorale – 1919

- 코리동 Corydon – 1920

- 한 알의 밀이 죽지 않는다면 (1920)

- Numquid et tu . . .? – 1922

- Dostoïevsky – 1923

- Incidences – 1924

- Caractères – 1925

- 위폐범들 Les faux-monnayeurs – 1925 (translated as The Counterfeiters – 1927)

- Si le grain ne meurt – 1926 (translated as If It Die)

- Le journal des faux-monnayeurs – 1926

- Dindiki – 1927

- 콩고 여행 Voyage au Congo – 1927

- Le retour de Tchad – 1928

- 여인들의 학교 L'école des femmes – 1929

- Essai sur Montaigne – 1929

- Un esprit non prévenu – 1929

- Robert – 1930

- La séquestrée de Poitiers – 1930

- L'affaire Redureau – 1930

- Œdipe – 1931

- Perséphone – 1934

- 우리들의 양식 Les nouvelles nourritures – 1935

- Geneviève – 1936

- 소련방문기 Retour de l'U. R. S. S. – 1936 Retouches â mon retour de l'U. R. S. S. – 1937

- Notes sur Chopin – 1938. 《쇼팽 노트》(임희근 역, 포노, 2015).

- Journal 1889–1939 – 1939

- Découvrons Henri Michaux – 1941

- Thésée – 1946

- Le retour – 1946

- 폴 발레리 Paul Valéry – 1947

- Le procès – 1947

- L'arbitraire – 1947

- Eloges – 1948

- Littérature engagée – 1950

같이 보기

[편집]André Gide

André Gide | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | André Paul Guillaume Gide 22 November 1869 Paris, France |

| Died | 19 February 1951 (aged 81) Paris, France |

| Resting place | Cimetière de Cuverville, Cuverville, Seine-Maritime |

| Occupation | Novelist, essayist, dramatist |

| Education | Lycée Henri-IV |

| Notable works | The Immoralist Strait Is the Gate Les caves du Vatican (The Vatican Cellars; sometimes published in English under the title Lafcadio's Adventures) The Pastoral Symphony The Counterfeiters The Fruits of the Earth |

| Notable awards | Nobel Prize in Literature 1947 |

| Spouse | Madeleine Rondeaux (m. 1895; died 1938) |

| Children | Catherine Gide |

| Signature | |

| |

André Paul Guillaume Gide (French: [ɑ̃dʁe pɔl ɡijom ʒid]; 22 November 1869 – 19 February 1951) was a French writer and author whose writings spanned a wide variety of styles and topics. He was awarded the 1947 Nobel Prize in Literature. Gide's career ranged from his beginnings in the symbolist movement, to criticising imperialism between the two World Wars. The author of more than fifty books, he was described in his obituary in The New York Times as "France's greatest contemporary man of letters" and "judged the greatest French writer of this century by the literary cognoscenti."[1]

Known for his fiction as well as his autobiographical works, Gide expressed the conflict and eventual reconciliation of the two sides of his personality (characterized by a Protestant austerity and a transgressive sexual adventurousness, respectively). Gide engaged in what is now considered as child rape; having sex with young boys who were not of the age of consent. However, the age of consent for sexual activity in France before 1945 was set at 13 years old (in 1945 an ordinance established an age of consent of 15). Gide glorified this heinous activity and was never legally held accountable. He suggested that a strict and moralistic education had helped set these facets at odds. Gide's work can be seen as an investigation of freedom and empowerment in the face of moralistic and puritanical constraints. He worked to achieve intellectual honesty. As a self-professed pederast, he used his writing to explore his struggle to be fully oneself, including owning one's sexual nature, without betraying one's values. His political activity was shaped by the same ethos. While sympathetic to Communism in the early 1930s, as were many intellectuals, after his 1936 journey to the USSR he supported the anti-Stalinist left; during the 1940s he shifted towards more traditional values and repudiated Communism as an idea that breaks with the traditions of the Christian civilization.

Early life

[edit]

Gide was born in Paris on 22 November 1869 into a middle-class Protestant family. His father Jean Paul Guillaume Gide was a professor of law at University of Paris; he died in 1880, when the boy was eleven years old. His mother was Juliette Maria Rondeaux. His uncle was political economist Charles Gide. His paternal family traced its roots to Italy. The ancestral Guidos had moved to France and other western and northern European countries after converting to Protestantism during the 16th century, and facing persecution in Catholic Italy.[2][3][4]

Gide was brought up in isolated conditions in Normandy. He became a prolific writer at an early age, publishing his first novel The Notebooks of André Walter (French: Les Cahiers d'André Walter), in 1891, at the age of twenty-one.

In 1893 and 1894, Gide travelled in Northern Africa. There he came to accept his attraction to boys and youths.[5]

Gide befriended Irish playwright Oscar Wilde in Paris, where the latter was in exile. In 1895 the two men met in Algiers. Wilde had the impression that he had introduced Gide to homosexuality, but Gide had discovered homosexuality on his own.[6][7]

The middle years

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2017) |

In 1895, after his mother's death, Gide married his cousin Madeleine Rondeaux,[8] but the marriage remained unconsummated. In 1896, he was elected mayor of La Roque-Baignard, a commune in Normandy.

Gide spent the summer of 1907 in Jersey, with friends Jacques Copeau and Théo van Rysselberghe and their families. He rented a room in La Valeuse Cottage in St Brelade. Whilst there he worked on the second chapter of Strait Is the Gate (French: La Porte étroite), and van Rysselberghe painted his portrait.[9]

In 1908, Gide helped found the literary magazine Nouvelle Revue Française (The New French Review).[10]

During World War I, Gide visited England. One of his friends there was artist William Rothenstein. Rothenstein described Gide's visit to his Gloucestershire home in his autobiography:

In 1916, Gide was about 47 years old when he took Marc Allégret, age 15, as a lover. Marc was one of five children of Élie Allégret and his wife. Gide had become friends with the senior Allégret during his own school years when Gide's mother had hired Allégret as a tutor for her son. Élie Allégret had been best man at Gide's wedding. After Gide fled with Marc to London, his wife Madeleine burned all his correspondence in retaliation– "the best part of myself," Gide later commented.

In 1918, Gide met and befriended Dorothy Bussy; they were friends for more than 30 years, and she translated many of his works into English.

Gide also became close friends with the critic Charles Du Bos.[12] Together they were part of the Foyer Franco-Belge, in which capacity they worked to find employment, food and housing for Franco-Belgian refugees who arrived in Paris following the 1914 German invasion of Belgium.[13][14] Their friendship later declined, due to Du Bos's perception that Gide had disavowed or betrayed his spiritual faith, in contrast to Du Bos's own return to faith.[15][16]

Du Bos's essay Dialogue avec André Gide was published in 1929.[17] The essay, informed by Du Bos's Catholic convictions, condemned Gide's homosexuality.[18] Gide and Du Bos's mutual friend Ernst Robert Curtius criticised the book in a letter to Gide, writing that "he [Du Bos] judges you according to Catholic morals suffices to neglect his complete indictment. It can only touch those who think like him and are convinced in advance. He has abdicated his intellectual liberty."[19]

In the 1920s, Gide became an inspiration for such writers as Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre. In 1923, he published a book on Fyodor Dostoyevsky. When he defended homosexuality in the public edition of Corydon (1924), he received widespread condemnation. He later considered this his most important work.

In 1923, Gide sired a daughter, Catherine, by Elisabeth van Rysselberghe, a much younger woman. He had known her for a long time, as she was the daughter of his friends Maria Monnom and Théo van Rysselberghe, a Belgian neo-impressionist painter. This caused the only crisis in the long-standing relationship between Allégret and Gide, and damaged his friendship with Théo van Rysselberghe. This was possibly Gide's only sexual relationship with a woman,[20] and it was brief in the extreme. Catherine was his only descendant by blood. He liked to call Elisabeth "La Dame Blanche" ("The White Lady").

Elisabeth eventually left her husband to move to Paris and manage the practical aspects of Gide's life (they had adjoining apartments built on the rue Vavin). She worshipped him, but evidently they no longer had a sexual relationship.[citation needed]

In 1924, he published an autobiography If it Die... (French: Si le grain ne meurt). In the same year, he produced the first French-language editions of Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness and Lord Jim.

After 1925, Gide began to campaign for more humane conditions for convicted criminals. His legal wife, Madeleine Gide, died in 1938. Later he explored their unconsummated marriage in Et nunc manet in te, his memoir of Madeleine, published in English in the United States in 1952.

Africa

[edit]From July 1926 to May 1927, Gide traveled through the colony of French Equatorial Africa with his lover Marc Allégret. They went successively to Middle Congo (now the Republic of the Congo), Ubangi-Shari (now the Central African Republic), briefly to Chad and then to Cameroon. He kept a journal, which he published as Travels in the Congo (French: Voyage au Congo) and Return from Chad (French: Retour du Tchad).[10]

In this work, he criticized the behavior of French business interests in the Congo and inspired reform.[10] In particular, he strongly criticized the Large Concessions regime (French: Régime des Grandes Concessions). The government had conceded part of the colony to French companies, allowing them to exploit the area's natural resources, in particular rubber. He related that native workers were forced to leave their village for several weeks to collect rubber in the forest, and compared their exploitation by the companies to slavery. The book contributed to the growing anti-colonialism movements in France and helped thinkers to re-evaluate the effects of colonialism in Africa.[21]

Political views and the Soviet Union

[edit]During the 1930s, Gide briefly became a Communist, or more precisely, a fellow traveler (he never formally joined any Communist party), but he, an individualist himself, advocated the idea of Communist individualism.[22] Despite supporting the Soviet Union, he acknowledged the political repression in the USSR. Gide insisted on the release of Victor Serge, a Soviet writer and a member of the Left Opposition who was prosecuted by the Stalinist regime for his views.[23][24] As a distinguished writer sympathizing with the cause of Communism, he was invited to speak at Maxim Gorky's funeral and to tour the Soviet Union as a guest of the Soviet Union of Writers. He encountered censorship of his speeches and was particularly disillusioned with the state of culture under Soviet Communism. In his work, Retour de L'U.R.S.S. (Return from the USSR, 1936), he broke with such socialist friends as Jean-Paul Sartre[citation needed]; the book was addressed to pro-Soviet readers, so the purpose was to expose a reader to doubts instead of presenting harsh criticism.[24] While admitting the economic and social achievements of the USSR compared to the Russian Empire, he noted the decay of culture, the erasure of the individuality of Soviet citizens, and the suppression of any dissent:

Gide does not express his attitude towards Stalin, but he describes the signs of his personality cult: "in each [home], ... the same portrait of Stalin, and nothing else"; "portrait of Stalin... , in the same place no doubt where the icon used to be. Is it adoration, love, or fear? I do not know; always and everywhere he is present."[26] However, Gide wrote that these problems could be solved by raising the cultural level of Soviet society.

When Gide began preparing his manuscript for publication, the Kremlin was immediately informed about it,[27] and soon Gide would be visited by the Soviet author Ilya Ehrenburg, who said that he agreed with Gide, but asked to postpone the publication, as the Soviet Union assisted the Republicans in Spain; two days later, Louis Aragon delivered a letter from Jef Last asking to postpone the publication. These measures didn't help, and as the book was published, Gide was condemned in the Soviet press[27][24] and by the "friends of the USSR": Nordahl Grieg wrote that the reason of writing the book was Gide's impatience, and that with his book he made a favour to the Fascists, who greeted it with joy.[28] In 1937, in response, Gide published Afterthoughts on the U. S. S. R.; earlier, Gide read Trotsky's The Revolution Betrayed and met Victor Serge who provided him more information about the Soviet Union.[24] In Afterthoughts, Gide is more direct in his criticism of the Soviet society: "Citrine, Trotsky, Mercier, Yvon, Victor Serge, Leguay, Rudolf and many others have helped me with their documentation. Everything they have taught me so far I had only suspected it – has confirmed and reinforced my fears".[29] The main points of Afterthoughts were that the dictatorship of the proletariat became the dictatorship of Stalin, and that the privileged bureaucracy became the new ruling class which profited by the workers' surplus labour, spending the state budget on projects like the Palace of Soviets or to raise its own standards of living, while the working class lived in extreme poverty; Gide cited the official Soviet newspapers to prove his statements.[29][24][30]

During the World War II Gide came to a conclusion that "absolute liberty destroys the individual and also society unless it be closely linked to tradition and discipline"; he rejected the revolutionary idea of Communism as breaking with the traditions, and wrote that "if civilization depended solely on those who initiated revolutionary theories, then it would perish, since culture needs for its survival a continuous and developing tradition." In Thesee, written in 1946, he showed that an individual may safely leave the Maze only if "he had clung tightly to the thread which linked him with the past". In 1947, he said that although during the human history the civilizations rose up and died, the Christian civilization may be saved from doom "if we accepted the responsibility of the sacred charge laid on us by our traditions and our past." He also said that he remained an individualist and protested against "the submersion of individual responsibility in organized authority, in that escape from freedom which is characteristic of our age."[22]

Gide contributed to the 1949 anthology The God That Failed. He could not write an essay because of his state of health, so the text was written by Enid Starkie, based on paraphrases of Return from the USSR, Afterthoughts, from a discussion held in Paris at l'Union pour la Verite in 1935, and from his Journal; the text was approved by Gide.[22]

1930s and 1940s

[edit]In 1930 Gide published a book about the Blanche Monnier case titled La Séquestrée de Poitiers, changing little but the names of the protagonists. Monnier was a young woman who was kept captive by her own mother for more than 25 years.[31][32]

In 1939, Gide became the first living author to be published in the prestigious Bibliothèque de la Pléiade.

He left France for Africa in 1942 and lived in Tunis from December 1942 until it was re-taken by French, British and American forces in May 1943 and he was able to travel to Algiers where he stayed until the end of World War II.[33] In 1947, he received the Nobel Prize in Literature "for his comprehensive and artistically significant writings, in which human problems and conditions have been presented with a fearless love of truth and keen psychological insight".[34] He devoted much of his last years to publishing his Journal.[35] Gide died in Paris on 19 February 1951. The Roman Catholic Church placed his works on the Index of Forbidden Books in 1952.[36]

Gide's life as a writer

[edit]Gide's biographer Alan Sheridan summed up Gide's life as a writer and an intellectual:

"Gide's fame rested ultimately, of course, on his literary works. But, unlike many writers, he was no recluse: he had a need of friendship and a genius for sustaining it."[38] But his "capacity for love was not confined to his friends: it spilled over into a concern for others less fortunate than himself."[39]

Writings

[edit]André Gide's writings spanned many genres – "As a master of prose narrative, occasional dramatist and translator, literary critic, letter writer, essayist, and diarist, André Gide provided twentieth-century French literature with one of its most intriguing examples of the man of letters."[40]

But as Gide's biographer Alan Sheridan points out, "It is the fiction that lies at the summit of Gide's work."[41] "Here, as in the oeuvre as a whole, what strikes one first is the variety. Here, too, we see Gide's curiosity, his youthfulness, at work: a refusal to mine only one seam, to repeat successful formulas...The fiction spans the early years of Symbolism, to the "comic, more inventive, even fantastic" pieces, to the later "serious, heavily autobiographical, first-person narratives"...In France Gide was considered a great stylist in the classical sense, "with his clear, succinct, spare, deliberately, subtly phrased sentences."

Gide's surviving letters run into the thousands. But it is the Journal that Sheridan calls "the pre-eminently Gidean mode of expression."[42] "His first novel emerged from Gide's own journal, and many of the first-person narratives read more or less like journals. In Les faux-monnayeurs, Edouard's journal provides an alternative voice to the narrator's." "In 1946, when Pierre Herbert asked Gide which of his books he would choose if only one were to survive," Gide replied, 'I think it would be my Journal.'" Beginning at the age of 18 or 19, Gide kept a journal all of his life and when these were first made available to the public, they ran to 1,300 pages.[43]

Struggle for values

[edit]"Each volume that Gide wrote was intended to challenge itself, what had preceded it, and what could conceivably follow it. This characteristic, according to Daniel Moutote in his Cahiers de André Gide essay, is what makes Gide's work 'essentially modern': the 'perpetual renewal of the values by which one lives.'"[44] Gide wrote in his Journal in 1930: "The only drama that really interests me and that I should always be willing to depict anew, is the debate of the individual with whatever keeps him from being authentic, with whatever is opposed to his integrity, to his integration. Most often the obstacle is within him. And all the rest is merely accidental."[45]

As a whole, "The works of André Gide reveal his passionate revolt against the restraints and conventions inherited from 19th-century France. He sought to uncover the authentic self beneath its contradictory masks."[46]

Sexuality

[edit]In his journal, Gide distinguishes between adult-attracted "sodomites" and boy-loving "pederasts", categorizing himself as the latter.

Gide's journal documents his behavior in the company of Oscar Wilde.

Gide's novel Corydon, which he considered his most important work, includes a defense of pederasty. At that time (before 1945), the age of consent for any type of sexual activity was set at 13.

Bibliography

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "New York Times obituary". www.andregide.org. Archived from the original on 6 August 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ Wallace Fowlie, André Gide: His Life and Art, Macmillan (1965), p. 11

- ^ Pierre de Boisdeffre, Vie d'André Gide, 1869–1951: André Gide avant la fondation de la Nouvelle revue française (1869–1909), Hachette (1970), p. 29

- ^ Jean Delay, La jeunesse d'André Gide, Gallimard (1956), p. 55

- ^ If It Die: Autobiographical Memoir by André Gide (first edition 1920, Vintage Books, 1935, translated by Dorothy Bussy: "but when Ali – that was my little guide's name – led me up among the sandhills, in spite of the fatigue of walking in the sand, I followed him; we soon reached a kind of funnel or crater, the rim of which was just high enough to command the surrounding country...As soon as we got there, Ali flung the coat and rug down on the sloping sand; he flung himself down too, and stretched on his back...I was not such a simpleton as to misunderstand his invitation"..."I seized the hand he held out to me and tumbled him on to the ground." [p. 251]

- ^ Out of the past, Gay and Lesbian History from 1869 to the present (Miller 1995:87)

- ^ If It Die: Autobiographical Memoir by André Gide (first edition 1920) (Vintage Books, 1935, translated by Dorothy Bussy: "I should say that if Wilde had begun to discover the secrets of his life to me, he knew nothing as yet of mine; I had taken care to give him no hint of them, either by deed or word....No doubt, since my adventure at Sousse, there was not much left for the Adversary to do to complete his victory over me; but Wilde did not know this, nor that I was vanquished beforehand or, if you will...that I had already triumphed in my imagination and my thoughts over all my scruples." [p. 286])

- ^ "André Gide (1869–1951) – Musée virtuel du Protestantisme". www.museeprotestant.org. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ Moore, Diane Monier (2024). Immoralists and Drama Queens: André Gide, Théo Van Rysselberghe and their colourful entourage, Jersey 1907-1909. Blue Ormer. ISBN 978-1-915786-12-8.

- ^ a b c André Gide on Nobelprize.org

- ^ William Rothenstein, Men and Memories, Faber & Faber, 1932, p. 344

- ^ Woodward, Servanne (1997). "Du Bos, Charles". In Chevalier, Tracy (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Essay. Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. p. 233. ISBN 978-1-135-31410-1.

- ^ Davies, Katherine Jane (2010). "A 'Third Way' Catholic Intellectual: Charles Du Bos, Tragedy, and Ethics in Interwar Paris". Journal of the History of Ideas. 71 (4): 655. doi:10.1353/jhi.2010.0005. JSTOR 40925953. S2CID 144724913.

- ^ Price, Alan (1996). The End of the Age of Innocence: Edith Wharton and the First World War. St. Martin's Press. pp. 28–9. ISBN 978-1-137-05183-7.

- ^ Dieckmann, Herbert (1953). "André Gide and the Conversion of Charles Du Bos". Yale French Studies (12): 69. doi:10.2307/2929290. JSTOR 2929290.

- ^ Woodward 1997, p. 233.

- ^ Einfalt, Michael (2010). "Debating Literary Autonomy: Jacques Maritain versus André Gide". In Heynickx, Rajesh; De Maeyer, Jan (eds.). The Maritain Factor: Taking Religion into Interwar Modernism. Leuven University Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-90-5867-714-3.

- ^ Einfalt 2010, p. 158.

- ^ Einfalt 2010, p. 160.

- ^ White, Edmund (10 December 1998). "On the chance that a shepherd boy …". London Review of Books. 20 (24): 3–6. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ Voyage au Congo suivi du Retour du Tchad Archived 16 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine, in Lire, July–August 1995 (in French)

- ^ a b c The God that failed chinhnghia.com

- ^ "Victor Serge: The Spirit of Liberty". 23 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Alan Sheridan. André Gide: A Life in the Present (1999)

- ^ Return from the U. S. S. R. translated in English, D. Bussy (Alfred Knopf, 1937), pp. 41–42

- ^ Return from the U. S. S. R. translated in English, D. Bussy (Alfred Knopf, 1937), pp. 25; 45

- ^ a b "Andre Gide's Retour de L'U.R.S.S. and Its Publication History: A View from the Kremlin".

- ^ The Making of an Antifascist: Nordahl Grieg Between the World Wars. University of Wisconsin Pres. 14 June 2022. ISBN 978-0-299-33650-9.

- ^ a b Afterthoughts: A Sequel to Back from the U.S.S.R (1937)

- ^ Gide answers his Bolshevik critics libcom.org

- ^ Pujolas, Marie. En tournage, un documentaire sur l'incroyable affaire de "La séquestrée de Poitiers". France TV info. Feb 27, 2015 [1]

- ^ Levy, Audrey. Destins de femmes: Ces Poitevines plus ou moins célèbres auront marqué l'Histoire. Le Point. Apr 21, 2015. [2]

- ^ O'Brien, Justin (1951). The Journals of Andre Gide Volume IV 1939–1949. Translated from the French. Secker & Warburg.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Literature 1947". www.nobelprize.org. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ "André Gide (1869–1951)". Musée virtuel du Protestantisme français. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- ^ André Gide Biography (1869–1951). eninimports.com

- ^ André Gide: A Life in the Present by Alan Sheridan. Harvard University Press, 1999, p. xvi.

- ^ Alan Sheridan, p. xii.

- ^ Alan Sheridan, p. 624.

- ^ Article on André Gide in Contemporary Authors Online 2003.

- ^ Information in this paragraph is extracted from André Gide: A Life in the Present by Alan Sheridan, pp. 629–33.

- ^ Information in this paragraph is extracted from André Gide: A Life in the Present by Alan Sheridan, p. 628.

- ^ Journals: 1889–1913 by André Gide, trans. by Justin O'Brien, p. xii.

- ^ Quote taken from the article on André Gide in Contemporary Authors Online, 2003.

- ^ Journals: 1889–1913 by André Gide, trans. by Justin O'Brien, p. xvii.

- ^ Quote taken from the article on André Gide in the Encyclopedia of World Biography, Dec. 12, 1998, Gale Pub.

- ^ Gide, Andre (1948). The Journals Of André Gide, Vol II 1914–1927. Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 246–247. ISBN 978-0-252-06930-7. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ^ Weinberg, Herman G., 1967. Josef von Sternberg. A Critical Study. New York: Dutton p. 121. Weinberg notes "Gide replied testily, with that refined distinction so characteristic of him…"

- ^ Gide, Andre (1935). If It Die: An Autobiography (New ed.). Random House. p. 288. ISBN 978-0-375-72606-4. Retrieved 27 April 2016.. Viewable here: Gide, André (22 January 1963). "If it die : an autobiography [archived]". Internet Archive. Retrieved 14 May 2023. Note: some editions of this same work omit this section.

Works cited

[edit]- Edmund White, [3] André Gide: A Life in the Present. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998]

Further reading

[edit]- Noel I. Garde [Edgar H. Leoni], Jonathan to Gide: The Homosexual in History. New York:Vangard, 1964. OCLC 3149115

- For a chronology of Gide's life, see pp. 13–15 in Thomas Cordle, André Gide (The Griffin Authors Series). Twayne Publishers, Inc., 1969.

- For a detailed bibliography of Gide's writings and works about Gide, see pp. 655–678 in Alan Sheridan, André Gide: A Life in the Present. Harvard, 1999.

External links

[edit]André Gide

- Website of the Catherine Gide Foundation, held by Catherine Gide, his daughter

- Center for Gidian Studies

- Works by André Gide at Project Gutenberg

- Works by André Gide at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about André Gide at the Internet Archive

- List of Works

- Works by André Gide at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- André Gide at Goodreads

- Amis d'André Gide in French

- Period newspaper articles on Gide interface in French

- André Gide, 1947 Nobel Laureate for Literature

- André Gide: A Brief Introduction

- Gide at Maderia in Jersey, 1901–07

- Newspaper clippings about André Gide in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- 1869 births

- 1951 deaths

- Writers from Paris

- French novelists

- French Protestants

- French travel writers

- French anti-communists

- French communists

- Nobel laureates in Literature

- French Nobel laureates

- Writers about the Soviet Union

- Modernist writers

- Fyodor Dostoyevsky scholars

- Lycée Henri-IV alumni

- French male essayists

- French male novelists

- French people of Italian descent

- Anti-Stalinist left

- Nouvelle Revue Française editors

The Fruits of the Earth

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2010) |

(publ. Alfred A. Knopf, 1949)

The Fruits of the Earth (French: Les nourritures terrestres) is a prose-poem by André Gide, published in France in 1897. A second part, French: Nouvelles nourritures ("Later Fruits") was added in 1935.

The book was written in 1895 (the year of Gide's marriage) and appeared in a review in 1896 before publication the next year. Gide admitted to the intellectual influence of Nietzsche's Thus Spoke Zarathustra[1] but the true genesis was the author's own journey from the deforming influence of his puritanical religious upbringing to liberation in the arms of North African boys. Andre Maurois draws attention to the similarity of moral outlook between the two works in these words: "Like Thus Spake Zarathustra, Les Nourritures Terrestres is a gospel in the root sense of the word: glad tidings. Tidings about the meaning of life addressed to a dearly loved disciple whom Gide calls Nathanael."[2] "Nathanael" comes from the Hebrew name נְתַנְאֵל, "Nethan'el", meaning "God has given".[3]

The book has three characters: the narrator, the narrator's teacher, Menalque, and the young Nathanael. Menalque has two lessons to impart through the narrator. The first is to flee families, rules, stability. Gide himself suffered so much from "snug homes" that he harped on its dangers all his life. The second is to seek adventure, excess, fervor; one should loathe the lukewarm, security, all tempered feelings. "Not affection, Nathanael: love ..."

A subtly structured collection of lyrical fragments, reminiscences, poems, travel notes, and aphorisms, the book came to command such a following after World War I that Gide wrote a preface stressing the work's self-critical dimension. Nevertheless it influenced a generation of young writers, including a young Jacques Derrida[4] and the existentialists Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre, to cast off all that is artificial or merely conventional.[5] In Roger Martin du Gard’s The Thibaults, two of the main characters, Jacques Thibault and Daniel de Fontanin, are deeply changed after reading the book.

References

[edit]- ^ Catherine Hill Savage, Les nourritures terrestres and Also Sprach Zarathustra

- ^ Andre Maurois, "From Proust to Camus: Profiles of Modern French Writers"

- ^ MFnames.com - Origin and Meaning of Nathanael

- ^ Peeters, Benoît (2013). Derrida: A Biography. Polity Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-7456-5615-1.

- ^ Liukkonen, Petri. "André Gide". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 24 November 2014.

External links

[edit]- Les nourritures terrestres, original French version in the public domain at archive.org

책은 도끼다 (완독)

지상의 양식 (앙드레 지드)

독서천재 정태유

2021. 10. 9. 6:30

이웃추가

본문 기타 기능

"당신이 기쁨에 바치는 책 속에 대체 왜 이런 이야기가 나오는 거죠?"

"이 이야기를 더 간단하게 할 생각이었습니다만. 사실 불행을 딛고서 얻는 행복이라면 나는 원치 않습니다. 다른 사람에게서 빼앗아 얻는 재물이라면 나는 원치 않습니다.

내 옷이 남을 헐벗게 하는 것이라면 나는 벌거숭이로 지내겠어요. 아, 하느님 그리스도여, 당신은 식탁을 개방해 두고 계십니다! 당신의 왕국의 향연이 이토록 아름다운 것은 만인이 거기에 초대받은 것이기 때문입니다."

안녕하세요, 하루에 한 권 독서천재 정태유입니다.

앙드레 지드의 《지상의 양식》을 드디어 읽었습니다. 책을 산 지는 거의 2년이 다 되어 가는 것 같네요. 이럴 때는 드디어 이 책을 읽었다는 다소 안도하는 느낌이라고나 할까요?

그러면서 또 한 편으로는 나 스스로에 대한 부끄러움이 앞서는 기분입니다.

'당신 정도면 당연히 진작에 읽었어야 하는 거 아닌가?'

누군가 이렇게 저에게 말하고 있는 것 같기 때문입니다. 사실 저 스스로도 '독서천재라면서 아직도 이 책을 안 읽었나?'하는 생각이 들기도 하지요.

이 책 제목에 나오는 양식은 우리가 생각하는 그런 양식(糧食)입니다. 지상의 양식, 지구 위의 음식, 뭐 이런 뜻이죠. '책은 마음의 양식이다'라는 유명한 말이 있듯이 그럴 때 쓰는 양식입니다.

그런데 정말 대단한 것은 이 책의 구성입니다. 제목과 마찬가지로 첫 챕터 1부는 '지상의 양식'입니다. 1897년에 출간되었죠. 지드 자신의 나이가 스물아홉 살, 아직 이십대의 나이에 쓴 것입니다.

아직 피 끓는 젊은 나이에 자신의 시선으로 바라보는 세상. 그 세상은 모든 것을 포함하고 있는 것입니다. 그러다 보니 세상이 정해 놓은 각각의 기준(정치, 종교, 문화, 사회 등 모든 것)에 대해서 상당히 반항적인, 모든 기준을 자기 스스로 재정립하려는 듯 글을 써 내려갑니다.

언제 어디서든 무엇이든 할 수 있다는 젊음이 가진 패기, 그 최고의 무기를 가지고 세상을 바라보는 것이죠.

그렇지만 책의 후반부에는 '새로운 양식'이 있습니다. 이것은 1935년에 출간되었습니다. 무려 그 시차가 38년입니다. 거의 70이 다 된 나이에 새로운 양식이라며 책을 썼습니다.

20대에 바라본 세상과는 달리 60대 후반에 바라본 세상은 어땠을까요? 누구나 상상을 할 수 있듯이, 그는 이제 세상이 돌아가는 방법에 대해서 그 시스템을 받아들였습니다.

한때 자신이 생각했던 내용들 중에 틀린 것도 다른 것도 많았다는 것을 인정하고, 스스로 순응하는 모습을 글로 적었습니다. 자신의 지난 삶을 되돌아보니 후회할 일이 그토록 많았다는 것을 깨닫고 인정합니다.

그리고 제가 이 한 권의 책 속에서 읽고 깨달은 내용 중에 가장 중요한 것은 이것이었습니다. 앞으로의 내 삶을 단 한 줄을 적는다고 한다면 바로 이 문장입니다.

나의 행복은 남들의 행복을 증가시키는 데 있다. 나 자신이 행복하려면 만인이 행복해질 필요가 있다.

저 또한 제 삶의 목적을 이렇게 표현하고 싶었거든요. 메신저로서의 삶을 넘어 선한 영향력을 전하는 삶. 그것이 곧 남을 행복하게 해 줌으로써 내가 행복해질 수 있다는 사실입니다.

고전문학이라는 게 그렇습니다. 그냥 딱 책을 보는 순간 일단 펼쳐서 읽기에 상당한 부담감을 갖습니다. 나도 모르게 '다음번에'로 미루려는 생각이 들곤 하죠.

하지만 어렵더라도 막상 읽고 나면 그 성취감은 가히 최고입니다. 아, 내가 드디어 읽었구나. 그리고 책 속에서 깨달은 내용도 다시 한번 생각해 보게 됩니다.

그리고 또 한 가지, 남들에게 권해주고 싶은 책 한 권을 마음속에 추가하고, 또 그 속에서 읽은 문장을 추가하는 겁니다. 오늘 하루 내가 나이를 먹었지만 그만큼 또 나는 삶의 지혜를 얻은 것입니다.

독서천재와 함께 하는 오늘의 책 앙드레 지드의 《지상의 양식》입니다. 오늘 하루 마음속 양식과 함께 행복하게 보내시길 기원합니다. 고맙습니다!

- 지상의 양식 (1897)

- 새로운 양식 (1935)

저자 앙드레 지드(André Paul Guillaume Gide) 는......

1869년, 파리 법과 대학 교수인 아버지와 루앙의 유복한 사업가 집안 출신의 어머니 사이에서 태어났다. 격정적인 성격에 몸이 허약했던 지드는 11세에 아버지가 사망하자 어머니와 외사촌 누이들에게 에워싸여 엄격한 청교도적 분위기 속에서 성장했는데, 이 무렵부터 신경 쇠약에 시달렸다.

1891년 청년기의 불안을 담은 자전적 소설 《앙드레 왈테르의 수첩》을 발표하며 문단에 데뷔했고, 이후 상징주의 시인 스테판 말라르메가 주도하는 ‘화요회’를 통해 문인들과 교류하면서 본격적인 작가의 길을 걷기 시작했다.

1893년 북아프리카 여행 중 결핵을 앓고 나서 처음으로 삶의 희열과 동성애에 눈을 뜬 그는 마침내 모든 도덕적·종교적 구속에서 해방되어 귀국한다. 1909년 친구들과 함께 문예지 《N.R.F.》를 창간하면서 그의 엄격하고 고전적인 스타일은 20세기 전반 프랑스 문단에 막강한 영향력을 행사했다.

1894년 어머니가 사망하자 첫사랑이자 《좁은 문》(1909)을 비롯한 많은 작품에 영향을 미친 사촌누이 마를렌 롱도와 결혼했다. 1896년 27세의 젊은 나이로 노르망디 라로크 자치구의 시장으로 당선되었고, 이 시기에 젊음의 열광과 자유의 삶에 대한 고백록인 《지상의 양식》(1897)을 집필, 동세대 작가들에게 큰 파장을 불러일으켰다.

1908년에는 문학평론지 《신프랑스평론》을 창간, 프랑스 문단에 새로운 힘을 불어넣는 한편, 앙투안 드 생텍쥐페리, 장 콕토 등의 주요 작가를 발굴하기도 했다. 탁월한 서정성과 문체로 문학적 성공을 거둔 《좁은 문》을 필두로 《배덕자》(1902), 《바티칸의 지하도》(1914), 《전원 교향곡》(1919), 《사전꾼들》(1925) 등의 작품들을 발표하는 한편 에세이와 평론들, 사회 비판적인 기행문까지 다양한 분야에서 큰 족적을 남겼다.

1947년 진정한 도덕성의 탐구를 통해 새로운 인간 정신의 풍토를 만드는 데 기여한 공로를 인정받아 옥스퍼드 대학교에서 명예박사 학위를 받았고, 같은 해 11월 노벨 문학상을 수상했다. 1950년 문학적 노정과 삶의 기록이자 1938년 아내가 사망한 후 일생 동안 꾸준히 써 온 《일기》의 마지막 권을 발표 후, 이듬해 파리의 자택에서 폐 충혈로 82세를 일기로 세상을 떠났다.

(알라딘 작가 소개)

지상의 양식저자앙드레 지드출판민음사발매2007.10.10.

.jpg?type=w800)

.jpg?type=w800)

지상의 양식 (1897)

1장.

나타나엘이여, 도처(到處)가 아닌 다른 곳에서 신(神)을 찾기를 바라지 말라.

피조물은 저마다 신을 가리키지만 그 어느 것도 신을 드러내 보이지는 않는다. 우리의 시선이 제게 머물기만 하면 즉시 피조물은 저마다 우리를 신에게서 벗어나 버리게 하는 것이다.

다른 사람들은 작품을 발표하거나 일을 하고 있는데 나는 오히려 3년 동안이나 여행을 하며 머리로 배운 모든 것을 잊어버리려 했다. 배운 것을 비워버리는 그러한 작업은 느리고도 어려웠다.

그러나 그것은 사람들로부터 강요당했던 모든 배움보다 나에게는 더 유익하였으며, 진실로 교육의 시작이었다. 삶에 흥미를 갖기 위하여 우리가 얼마나 많은 노력을 해야 했는지 그대는 결코 알지 못하리라.

그러나 삶이 우리의 흥미를 끌게 된 지금 세상만사가 다 그렇듯이 - 그 흥미는 열광적인 것이 되리라. 잘못을 저지를 때보다 그것을 벌할 때 더 많은 쾌감을 느끼며 나는 즐거이 나의 육체를 벌했다.

그저 단순히 죄를 범하지 않는다는 것만으로도 나는 무한한 자부심을 느꼈던 것이다. 자신의 마음속에서 '공적(功積)'이라는 생각 자체를 아예 없애버릴 것. 정신에는 그것이야말로 커다란 장애인 것이다.

...... 우리의 나아갈 길들이 확실치 않아서 우리는 일생 동안 괴로워했다. 그대에게 뭐라고 말해야 좋을까? 생각해 보면 선택이란 어떤 것이든 무서운 것이다.

의무를 인도해 주지 않는 자유란 무서운 것이다. 어디를 둘러보아도 낯설기만 한 고장에서 하나의 길을 택해야 하는 것이니. 사람은 저마다 거기서 '자신만의' 발견을 하게 되는 것이다.

분명히 말하지만 그 발견이란 인적미답의 땅 아프리카에서 더듬어 가는 가장 불확실한 발자취도 그보다는 덜 불안할 터이니...... 그늘진 수풀들이 우리의 마음을 끌고, 아직 마르지 않은 샘터의 신기루들이......

그러나 샘물들은 오히려 우리가 샘솟기를 바라는 바로 그곳에 있으리라. 한 고장은 오직 우리가 다가가면서 그 고장을 형상화하게 됨에 따라 존재하게 되는 것이며 그 주위의 풍경은 차츰차츰 걸어가는 우리의 걸음 앞에 전개되는 것이 아니던가.

그리고 우리는 지평선 끝을 보지 못한다. 우리 곁에 있는 것일지라도 그것은 항시 다른 모습으로 변하며 이어지는 외관에 불과한 것이다.

나타나엘이여. 내 그대에게 기다림을 이야기해 주마. 나는 여름 동안 벌판이 기다리는 것을 보았다. 비가 조금이라도 내리기를 기다리는 것을. 길의 먼지들이 너무나 가벼워져서 바람이 일 때마다 날렸다.

그것은 이미 욕망이라기보다는 차라리 조바심이었다. 땅은 물을 더 많이 받아들이려는 듯이 말라 터지고 있었다. 광야의 꽃향기는 거의 견디기 어려울 지경이었다.

뙤약볕을 받아 모든 것이 몽롱해져 갔다. 우리는 매일 오후 테라스 밑으로 가서 혹독한 햇빛의 광채를 얼마간 피하면서 쉬었다. 바야흐로 꽃가루 가득한 솔방울 달린 나무들이 수분(受粉)을 멀리멀리 퍼뜨리려고 가지를 너울너울 흔들고 있는 때였다.

하늘에는 비구름이 엉키고 온 자연이 기다리고 있었다. 모든 새들마저 소리를 죽이는 너무나도 숨 막힐 듯 엄숙한 순간이었다. 땅에서 불같이 뜨거운 바람이 솟아올라 모든 것이 정신을 잃고 쓰러져 버릴 것만 같았다.

침엽수들의 꽃가루가 황금 연기처럼 가지들에서 쏟아졌다 - 이윽고 비가 내렸다.

나는 하늘이 새벽의 기다림으로 전율하는 것을 보았다. 하나씩 별들이 꺼져갔다. 목장은 이슬에 젖어 있었다. 공기는 싸늘한 애무 그 자체였다. 얼마 동안 어렴풋한 생명은 잠에 빠진 채 눈을 뜰 생각이 없는 듯.

아직도 피로가 가시지 않은 나의 머리는 어리둥절한 상태를 벗어나지 못했다. 나는 숲 기슭까지 올라갔다. 그리고 자리에 앉았다. 짐승들은 저마다 날이 새고 있음을 굳게 믿고 다시 움직이며 즐거움을 되찾았다.

그리고 생명의 신비가 나뭇잎들의 터진 구멍마다 퍼져 나오기 시작했다 - 이윽고 날이 밝았다. 나는 또 다른 새벽들을 보았다 - 나는 밤의 기다림을 보았다......

4장.

나는 들로 나를 따라온 미르틸에게 말했다. '이 매혹적인 아침, 이 안개, 이 빛, 이 서늘한 공기, 네 존재의 고동. 네가 이런 것에 송두리째 너를 바칠 줄 안다면 그것들은 너에게 얼마나 더 큰 감동을 줄 것인가.

너는 그 속에 있다고 여기지만 사실은 네 존재의 가장 귀한 부분이 갇혀 있는 것이다. 너의 아내, 너의 아이들, 너의 책들, 너의 공부가 그 귀한 부분을 놓아주지 않은 채 네가 신과 접촉하는 것을 방해하고 있는 것이다.'

'바로 이 순간에 너는 생의 벅차고 온전하고 직접적인 감동을 맛볼 수 있다고 생각하는가 - 그 밖의 것을 잊어버리지 않은 채? 네 사고의 습관이 너를 방해하고 있다.

너는 과거에 살고 미래에 살고 있어서 아무것도 자연 발생적으로 지각하지 못한다. 마르틸이여. 우리는 순간에 찍히는 사진과 같은 생을 벗어나면 아무것도 아니다.

앞으로 올 것이 생겨나기도 전에 거기서 과거는 송두리째 죽어버린다. 순간들! 미르틸이여. 너는 알게 될 것이다. 순간들의 '현존'이 얼마나 큰 힘을 가진 것인가를!

왜냐하면 우리 생의 각 순간은 본질적으로 다른 것과 바꿔질 수 없는 것이니 말이다. 때로는 오직 그 순간에만 온 마음을 기울일 줄 알아야 한다. 미르틸, 네가 원하기만 한다면, 네가 알기만 한다면, 너는 이 순간 아내도 자식도 잊어버리고,

지상에서 홀로 신 앞에 있을 수 있을 것이다. 그러나 너는 그들을 기억하고, 마치 너의 모든 과거, 사랑, 지상의 모든 관심사를 잃어버릴까 봐 겁이 난다는 듯 떠 짊어지고 다니는 것이다.

나로 말하면, 내 모든 사랑이 새로운 경이를 위하여 매 순간 나를 기다린다. 나는 언제나 새 사랑을 알 뿐 결코 옛사랑을 다시 알아보는 일은 없다. 미르틸, 신이 갖추게 되는 저 모든 형상들을 너는 짐작도 못 하고 있다.

그중 한 형상만을 너무 바라보고 그것에 심취한 나머지 장님이 되어버리고 마는 것이다. 너무나 고정된 너의 숭배가 보기에 딱하다. 좀 더 사방으로 퍼진 숭배였으면 싶다.

닫혀 있는 모든 문 뒤에 신은 있는 것이다. 신의 모든 형상은 사랑할 만한 것이며, 그리고 모든 것이 신의 형상인 것이다.'

6장.

로마에서는 핀치오 언덕 근처 바로 길가로 열려 있는, 감옥 창문처럼 창살이 달린 나의 방 창문 옆으로 꽃 파는 여인들이 다가와 내게 장미꽃을 사라고 내밀었다.

피렌체에서는 식탁에서 일어서지도 않은 채 노란빛 도는 아르노강이 넘쳐흐르는 것을 볼 수 있었다. 비스크라의 테라스에서는 메리엠이 밤의 깊고 엄청난 정적 속에 달빛을 받으면서 찾아왔다.

그녀는 웃음 지으며 유리문 안으로 들어서면서 온몸을 감싸고 있던 큼직한 흰빛의 찢어진 하이크를 슬쩍 떨어뜨렸다. 방 안에는 맛있는 과자들이 그녀를 기다리고 있었다.

그라나다에서는 나의 방 벽난로 위에 촛대 대신에 수박 두 개가 놓여 있었다. 세비야에는 '파치오'들이 있었다. 그건 그늘과 시원한 물이 모자람 없이 가득한 흰 대리석이 깔린 마당들을 두고 하는 말이다.

흐르는 물은 마당 한가운데 있는 수반 속에서 잔물결을 일으키며 찰랑거린다. 북풍을 막고 남쪽의 빛을 흡수하는 두꺼운 벽. 남방의 혜택을 투명하게 받아들이는 방랑하며 떠도는 집......

나다나엘이여, 우리에게 방이란 무엇이겠는가? 어느 풍경 속에서 비바람을 막아주는 한갓 은신처.

내 그대에게 또다시 창에 대하여 말해 주리라. 나폴리의 발코니 위에 앉아서 주고받던 이야기들. 밤에 여자들의 밝은 옷자락 곁에서 잠기던 몽상. 반쯤 늘어진 커튼이 우리를 소란한 무도장 안의 사람들과 격리시켜 주었다.

난처할 지경으로 섬세하게 신경을 쓰며 이야기를 주고받고 나면 얼마 동안 말없이 가만히 앉아 있는 것이었다. 이윽고 정원에서 견딜 수 없이 강렬한 오렌지 꽃 냄새와 여름밤의 새소리가 올라왔다.

그러다가 간간이 그 새소리마저 그치곤 했다. 그러면 파도 소리가 희미하게 들려왔다. 발코니. 등나무와 장미꽃 바구니. 저녁의 휴식. 따뜻한 기온.

8장.

나의 정신이여. 꿈같은 산책 중에 너는 유별나게 열광하였다.

오, 나의 마음이여! 나는 너를 넉넉하게 적셔주었다.

나의 육체여, 나는 너를 사랑으로 도취하게 하였다. 지금 휴식에 잠겨 나는 내 재산을 헤아려보고자 하지만 헛된 노릇이구나. 나에게는 재산이 없다.

이따금 나는 과거 속에서 한 무리의 추억들을 찾아 그것으로 마침내 이야기를 꾸며보려고 하지만 거기서 나는 내 모습을 알아볼 수가 없고 나의 삶은 그것을 넘쳐난다.

나는 항상 새로운 순간 속에서만 즉시 살 뿐이라는 느낌이 든다. 이른바 마음을 가다듬어 명상에 잠긴다는 것은 나에게는 불가능한 구속이다. 나는 이미 '고독'이라는 말의 의미를 알 수 없게 되었다.

나의 내면 속에 홀로 있다는 것은 아무도 아닌 것이 된다는 뜻이다. 나의 내면은 존재로 가득 차 있다 - 게다가 나는 도처(到處)에서가 아니면 내 집에 있는 것 같지가 않다.

그런데 언제나 욕망이 나를 거기서 몰아낸다. 가장 아름다운 추억도 나에게는 행복의 잔해에 지나지 않아 보인다. 아주 조그만 물방울이라도, 그것이 눈물 한 방울일지라도, 나의 손을 적셔주면 곧 나에게는 더 귀중한 현실이 된다.

새로운 양식 (1935)

1장.

이 땅 위에는 너무나 많은 가난과 비탄과 어려움과 끔찍한 일들이 가득해서 행복한 사람은 자기의 행복을 부끄러워하지 않고는 행복을 생각할 수 없다. 그러나 스스로 행복해질 수 없는 자는 남의 행복을 위하여 그 어떤 일도 할 수 없다.

나는 나 자신 속에 행복해야 할 절박한 의무를 느낀다. 그러나 남에게 피해를 주거나 남에게서 빼앗아야 비로소 얻을 수 있는 행복은 가증스럽게 여겨질 뿐이다.

한 걸음 더 나아가 우리는 비극적인 사회 문제에 직면한다. 내 이성의 모든 논리도 공산주의의 비탈 위에서 나를 지탱해 주지는 못할 것이다. 그런데 내가 보기에 잘못이라고 여겨지는 바는 가진 자에게 그가 가진 재물을 나누어 가지자고 요구하는 것이다.

그러나 가진 자에게서 그가 영혼을 다하여 애착을 지니고 있는 재물을 자발적으로 포기하기를 기대한다는 것은 얼마나 어이없는 망상인가. 나로서는 배타적인 소유에 대해서는 늘 혐오감을 느꼈다.

나의 행복은 오로지 증여로 이루어진 것이다. 그래서 죽음도 내 손에서 빼앗아 갈 것이 별로 없다. 죽음이 내게서 앗아 갈 수 있는 것이란 기껏해야 여기저기 흩어져 있어서 손에 넣을 수도 없는 자연적인 재물, 만인이 다 가질 수 있는 재물뿐이다.

특히 그런 것들이라면 나는 물릴 정도로 만끽했다. 그밖에 나는 가장 잘 차린 산해진미보다는 주막집의 식사를, 담장을 둘러친 가장 아름다운 정원보다는 공원을, 희귀본보다는 산책 갈 때 마음 놓고 들고 다녀도 좋은 책을 더 좋아한다.

그리고 어떤 예술 작품을 오직 나 혼자서만 감상해야 한다면 그 작품이 아름다울수록 즐거움보다는 슬픔이 앞설 것이다.

나의 행복은 남들의 행복을 증가시키는 데 있다. 나 자신이 행복하려면 만인이 행복해질 필요가 있다.

3장.

'돌이킬 수 없는 과거'에 대한 후회는 늙은이들이 마음 쓰는 가장 부질없는 일이다. 생각은 그렇게 하면서도 나는 그걸 극복하지 못하고 있다. 당신은 그 후회가 알지 못하는 사이에 신의 뜻을 되돌리게 하는 것이라고 믿기에 나를 그쪽으로 부추긴다.

그러나 당신은 나의 후회, 나의 회한의 성질에 대하여 오해하고 있다. 지금 나를 괴롭히는 것은 '행해지지 않은 것'에 대한 후회, 젊은 시절에 내가 할 수도 있었고 했어야 옳았으나 모랄 때문에 하지 못한 모든 것에 대한 후회다.

지금은 더 이상 신뢰하지도 않는 모랄, 자신의 육체를 만족시키는 것을 거부하는 데서 긍지를 느낄 정도로 나에게 가장 거추장스러운 것이면서도 거기에 순종하는 것이 좋다고 믿었던 그 모랄 때문에 말이다.

영혼과 육체가 사랑하기에 가장 알맞고 사랑하고 사랑받기에 가장 어울리는 나이, 포옹이 가장 힘차고 호기심이 가장 강하고 배울 것이 많으며 쾌락이 가장 값진 나이, 바로 그 나이에 영혼과 육체가 다 같이 사랑의 요구에 저항하는 최대의 힘을 갖추기 때문이다.

당신이 '유혹'이라고 불렀던 것, 내가 당신과 함께 유혹이라고 불렀던 것, 내가 애석하게 생각하는 점은 바로 그것이다. 오늘 내가 후회하는 것이 있다면 몇 가지 유혹에 졌기 때문이 아니라 너무나 많은 다른 유혹들에 저항했기 때문이다.

뒤늦게 그 유혹들이 이미 매력을 잃고 나의 사고에 별 도움이 되지 못하게 되었을 때 나는 그것을 찾아 헤매었던 것이다. 나는 나의 청춘을 어둡게 만든 것을, 현실보다 공상을 더 좋아했던 것을, 삶에 등을 돌리고 있었던 것을 후회한다.

작품 해설

《지상의 양식》 - 맨발에 닿는 세계의 생살, 혹은 소생의 희열

《지상의 양식》의 의미와 메시지를 정확하게 이해하고 음미하기 위해서는 책이 발표될 당시의 일반적 문학 경향과 정서 못지않게 이 책을 저자인 지드 자신의 개인적 삶과 관련하여 자리매김함으로써 해석해 보는 일이 반드시 필요하다.

이 책의 독자는 그 내용의 자전적인 성격에 강한 인상을 받지 않을 수 없다. 책의 화자는 단순히 새로운 윤리를 선언하는 것에 그치지 않는다. 그는 지금까지 자신이 살아온 과거의 여러 가지 경험을 되돌아보며 그것을 판단하고 거기서 어떤 교훈을 이끌어낸다.

그러므로 우리는 지드를 《지상의 양식》으로 인도하게 된 도정의 출발점으로 되돌아가서 그 이후의 정신적 행로를 간단히 되밟아 볼 필요가 있다.

《새로운 양식》 - 개인의 시각에서 만인의 지평으로

《지상의 양식》은 앙드레 발테르의 청소년기와 메날크의 청년기를 결산하는 작품이다. 그러나 이 작품을 실제로 집필하는 데 삼사 년의 기간이 소요되었을 뿐이다.

반면에 지드는 1919년에 이미 《새로운 양식》이라는 최종적인 제목을 붙인 책을 예고했고, 심지어 내용 중 어떤 대목은 1910 ~ 1911년에까지 소급되지만, 정작 완성된 책이 출판된 것은 그보다 훨씬 뒤인 1935년이었다.

다시 말해서 책이 구상되고 집필된 시기는 무려 사반세기가 넘는 긴 시간에 걸쳐 있는 것이다. 그러나 우리는 이본 다베의 다음과 같은 지적을 주목할 필요가 있다.

"이 책은 느린 속도로 다듬어진 작품이지만, 정확하게 말하자면 여러 차례에 걸쳐 구상을 시작해서 오랫동안 미완성인 채 방치했다가 결국에는 처음에 메모한 단장(短章)들의 영감과는 전혀 다른 각도의 관점에서 완성한 저작이다."

■ '책은 도끼다'에서 함께 읽으면 좋은 책들

====

===