Steve Newman Writer

Aug 9, 2020

Nikos Kazantzakis — Report to Greco

A Novelist of Passion and Patriotism

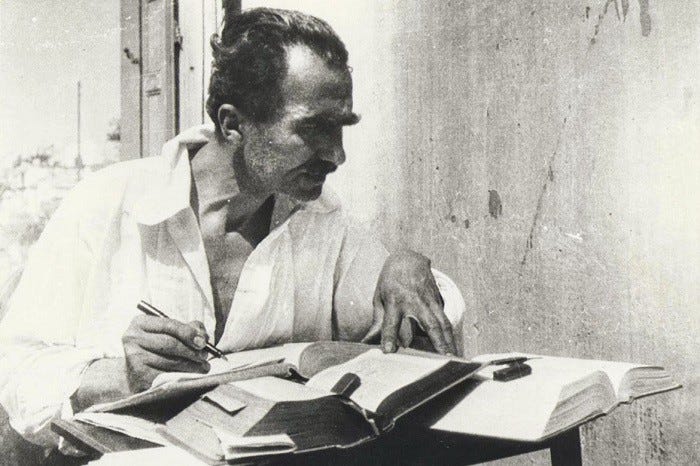

Kazantzakis. Iamge: greekreporter.com

Kazantzakis. Iamge: greekreporter.comNikos Kazantzakis was an extraordinary writer of passion and patriotism, and like a good many people I came to him through the film, Zorba the Greek, based on his novel, which was as good a way as any.

I saw the film in an open air cinema in Famagusta, Cyprus, in 1967, which drew quite a crowd, mainly locals, who sat through the film in silence, even though the film was quite funny in places. After the film, when the audience left the cinema, the Greek members of the audience looked solemn, some with tears in their eyes. It was pointed out to me just how important Kazantzakis was to the Greeks, not only as a writer but also as a saviour of their land and culture, and of their hopes.

I had to know more about this writer.

A couple of days after the film I came across a 1964 Faber & Faber copy of his novel, Christ Recrucified, in a Famagusta book shop, and found Nikos’s writing(translated from the Greek by Jonathan Griffin) totally absorbing and which Thomas Mann has described as a novel that is:

“ …without doubt a work of high artistic order formed by a tender and firm hand and built up with strong dynamic power. I have particularly admired the poetic tact in phrasing the subtle yet unmistakable allusions to the Christian passion story. They give the book its mythical background which is such a vital element in the epic form of today.”

On my return from Cyprus I became slightly obsessed with the life and works of Nikos Kazantzakis, who had been born, like my grandfather, in the 1880s, witnessing World War One, and the crumbling of the Ottoman Empire, and the conflicts between Crete and Turkey before that, the preamble to which he describes in his Report to Greco:

“ In time I saw clearly. The opponents were Crete and Turkey; Crete was battling to gain freedom, the other trampling on its breast and preventing it. After that everything around me acquired a face, the face of Crete and Turkey; in my imagination, and not only in my imagination but in my flesh as well, everything became a symbol reminding me of the terrible contest…”

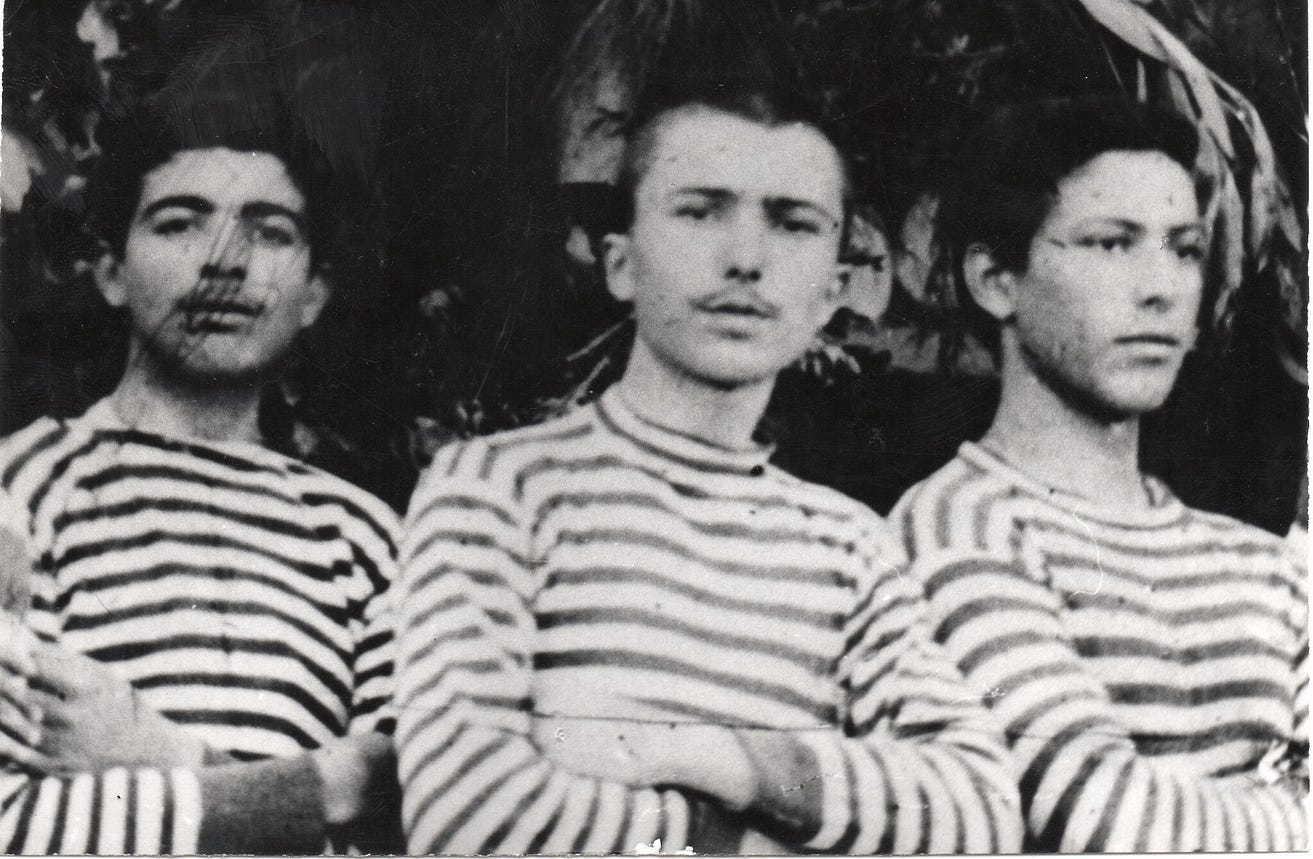

Nikos (centre) 1890s. Image: Archaelogy & Arts

Nikos (centre) 1890s. Image: Archaelogy & ArtsHelen Kazantzakis’s, in her 1968 biography of her husband, writes:

“ His youth, his adolescence, the bondage, the exile and the liberation, the first soft down shed upon encountering the strange and foreign world, the ideas, the women and the men who exerted influence on his thoughts or his body…”

Which is a poetic introduction to the man who personified modern Greek culture and intellectualism for so long, and to an undeniable extent still does. It was Kazantzakis’s writing and personality that helped rebuild the resilience and resistance of the Greek people : a resilience and resistance the Germans never expected to encounter during World War Two, and again just a few years ago in their struggle with the EU, and not least, Germany once more.

As Helen goes on to write:

“ There we find him, a little fellow with a top-heavy head, summoning the divine thunderbolts, when he could still barely stand on his own two feet in his mother’s courtyard…

“ And his first meeting with Death, in the cemetery where his uncle had taken him for a walk: Anica, the plump neighbor-lady, all perfumed and silky, reduced to a hideous skull which the gravedigger dug out of the earth with a swing of his shovel. A second and no less terrifying encounter when he was forced to kiss the feet of the heroes hanged by the Turks on the plane tree in the public square.

‘ I can’t, Father, I can’t…’

‘ You can. You must be able to…’

“ This mythological father who demanded just two things of his only son: not to tell lies and not to allow anyone to beat him. He had been prepared even as a small child to kill his mother and his sisters, should the Turks ever violate the ancestral threshold. ‘ Do you agree? We will kill them. We cannot allow them to be dragged into slavery. And the rest of us will defend ourselves like men. Do you know how to use this weapon?’

‘ I know how,’ murmured the child, who didn’t know how to kill a fly.’ ”

Nikos Kazantzakis was born the 18th of February 1883, in the village of Kandiye, near Heraklion, the capital of the island of Crete, which was then still a part of the Ottoman Empire. His ancestors, on his father’s side were “… bloodthirsty pirates on water, warrior chieftains on land, fearing neither God nor man.” His mother came from “…drab, goodly peasants who bowed trustfully over the soil the entire day, sowed, waited with confidence for rain and sun, reaped, and in the evening seated themselves on the stone bench in front of their homes, folded their arms, and placed their hopes in God.”

As Kazantzakis asked: “ Fire and soil. How could I harmonize these two militant ancestors inside me?” He goes on:

“ I felt this was my duty, my sole duty: to reconcile the irreconcilables, to draw the thick ancestral darkness out of my loins and transform it, to the best of my ability, into light.”

It was to be something he continued to do all his life, to try and drag his ancestors into the light of a new day, to somehow use their dark strengths in his search for the light of hope and victory, a victory that meant there was no need to kill one’s own mother and sisters if the Turks stepped onto their sacred island, and across the threshold of their sacred ancestral home.

Of his father Kazantzakis writes a great deal in Report to Greco, especially of those early days in Crete:

“ Once when he his father saw an aga [Turkish government official] place a packsaddle on a Christian and load him down like a donkey, so completely did his anger overcome him that he charged toward the Turk. He wanted to hurl an insult at him, but his lips had become contorted. Unable to utter a human word, he began to whinny like a horse. I was still only a child. I stood there and watched, trembling with fright.”

What the aga did Kazantzakis doesn’t say. He goes on to write:

“ And one midday as he [his father]was passing through a narrow lane on his way home for dinner, he heard a woman shrieking and doors being slammed. A huge drunken Turk with drawn yataghan [a bayonet-like sword] was pursuing Christians. He rushed upon my father the moment he saw him…”

Nikos’s father was in no mood for a fight and would have preferred to run, but the warrior and pirate deep inside him wouldn’t let him do that. Instead he wrapped his apron around his fist and when the huge Turk attacked him he bent low and thumped the Turk hard in the abdomen. He then picked up the yataghan and took his amazed son home. When they got home Nikos’ father threw the yataghan onto the sofa and told his wife to give Nikos the knife to use as a pencil sharpener when he was old enough to go to school.

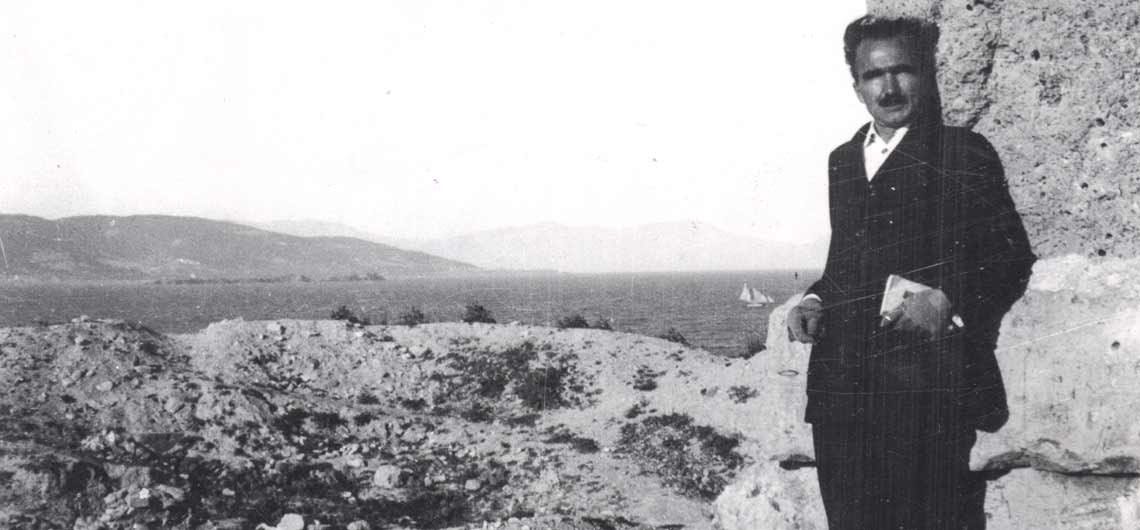

Image of Nikos: Nikos Kazantzakis Museum

Image of Nikos: Nikos Kazantzakis MuseumIn Report to Greco, Nikos Kazantzakis writes of going to school for the first time:

“ I was like a small sacrificial victim weighted down with ornaments. Within me I felt both pride and fear, but my hand was wedged deeply in my father’s grasp, and I bore myself with manly courage…”

Although Kazantzakis calls Report to Greco an autobiographical novel, his wife Helen, in her biography of her husband, hints that Greco is in fact a straight forward autobiography, albeit with some fictional touches. It’s what we would today call creative non-fiction, which is at the heart of most autobiographies anyway, or should be. Take another look at the work of Tolstoy and Hemingway to see what I mean.

Of course you have to be a good writer to make it work, or a great writer like Kazantzakis, to make it work really well.

In Greco Nikos draws you into his world with ease making his experience your experience:

“ Bending over, my father touched my hair and patted me. I gave a start, for as far as I could remember, this was the first time he had ever caressed me. Lifting my eyes, I glanced at him fearfully. He saw that I was afraid and withdrew his hand.

“ You’re going to learn to read and write here so you can become a man,” he said. “Cross yourself. ”

At this point the teacher appears, with a long switch in his hand who seemed, to Nikos, to be a savage with fangs. The future novelist looked for horns on the teacher’s head — just to be sure — but he was unable to see them because the teacher was wearing a hat. Nikos Kazantzakis can write with great wit.

‘ This is my son,’ my father said.

“ Untangling my hand from his own, he turned me over to the teacher.

‘ His bones are mine, his flesh is yours. Don’t feel sorry for him. Thrash him and make a man of him.’ ”

When Nikos started school, around 1888, the island had gone through long periods of uncertainty with many uprisings and rebellions against Ottoman rule(fuelled by Greece’s independence in 1830) with the Muslim and Christian populations more polarised than at any other period.

And as one section of a scholarly, Wikipedia article (based on the works of historians Adam Hopkins, Sally McKee, Theocharis Detorakis and Mick McTiernan) clarifies:

During the Congress of Berlin, in the summer of 1878, there was a further rebellion, which was halted quickly by the intervention of the British and the adaptation of the 1867–8 Organic Law into a constitutional settlement known as the Pact of Halepa. Crete became a semi-independent parliamentary state within the Ottoman Empire under an Ottoman Governor who had to be a Christian. A number of the senior “Christian Pashas” including Photiades Pasha and Kostis Adosidis Pasha ruled the island in the 1880s, presiding over a parliament in which liberals and conservatives contended for power.

Disputes between the two powers led to a further insurgency in 1889 and the collapse of the Pact of Halepa arrangements. The international powers, disgusted at what seemed to be factional politics, allowed the Ottoman authorities to send troops to the island and restore order but did not anticipate that Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II would use this as a pretext to end the Halepa Pact Constitution and instead rule the island by martial law. This action led to international sympathy for the Cretan Christians and to a loss of any remaining acquiescence among them for continued Ottoman rule. When a small insurgency began in September 1895, it spread quickly, and by the summer of 1896 the Ottoman forces had lost military control of most of the island…

Another Cretan insurrection in 1897 resulted in the Ottoman Empire declaring war on Greece, an action that led to an international naval force landing on the island and taking control. By 1898 all Ottoman troops had been expelled from the island, after which Crete became an independent state.

Throughout all of this the young Nikos was inspired and excited about the future, but knew he had to get on with his education if he had any chance of becoming a writer. And that education included a young teacher called What-cheese, and as Nikos clarifies:

He, “…reigned over… [our class]… but did not govern. He was pale, with spectacles, starched collar and shirt, pointed down-at-heel patent leather shoes, a huge hairy nose, and slender fingers yellowed from tobacco. His real name…was Papadakis. But one day his father, who was a priest in an outlying village, came to town bringing him a large head of cheese as a present. ‘What cheese is this Father?’ said the son. A neighbor happened to be at the house. She overheard, spread the word, and the poor teacher was roasted over the coals and given his nickname…”

For a young man who may already have become determined to be a great writer, the turmoil and passion of his homeland was at the heart of his thoughts, dreams and eventually his work. He learned quickly and well, enjoying Robinson Crusoe, and every other book What-cheese put in front of him.

During Kazantzakis time at school, the island had around six hundred elementary schools, with many young What-cheese teachers, some of whom may have studied in the university of Athens (as Kazantzakis would) where the message was Greek independence, with the consequence that many young Cretan pupils were fired-up with the same ideas: Crete must become independent. There would be many struggles ahead.

In many respects Nikos was already being educated out and away from his family where only one member, his father’s brother, had been to school, and when asked by Nikos what the word ‘birthright’ meant was told ‘hunting costume’. Nikos then told his father, who, in ignorance, agreed. It was the answer he gave What-cheese the following day.

“ What ignorant fool told you that?”

“ My uncle. And my father agreed.”

What-cheese, knowing the uncle and the father, who were big men, decided to use diplomacy.

“ Well, Nikos, it can mean that sometimes, in some cultures…”

It was to be a long and winding road.

Image of Nikos: benaki.gr

Image of Nikos: benaki.grAt the start of Report to Greco, Kazantzakis, as an introduction, writes:

“ My personal life has some value, extremely relative, for myself and no one else…Therefore, reader, in these pages you will find the red track made by drops of my blood, the track which marks my journey among men, passions, and ideas. Every man worthy of being called a son of man bears his cross and mounts his Golgotha. Many, indeed most, reach the first or second step, collapse pantingly in the middle of the journey, and do not attain the summit of Golgotha, in other words the summit of their duty: to be crucified, resurrected, and to save their souls. Afraid of crucifixion, they grow fainthearted; they do not know that the cross is the only path to resurrection. There is no other path.”

All of Kazantzakis’s work is the story of crucifixion (personal and national), of journeys toward death, of the narrator and the narrated, and of a sure resurrection, if only in a darkened room as tears and final breaths intermingle in memory, as was Zorba’s story.

Kazantzakis goes on to write:

“ The decisive steps in my ascent were four, and each bears a sacred name: Christ, Buddha, Lenin, Odysseus. This bloody journey from each of these great souls to the next is what I shall struggle to mark out in this itinerary, now that the sun has begun to set — the journey of a man with his heart in his mouth, ascending the rough, unaccommodating mountain of his destiny. My entire soul is a cry, and all my work the commentary on that cry.”

It is the cry of Crete, and of Greece, a cry of despair and hope, of bravery and disappointment, of life and courage, and rebirth.

What-Cheese taught the child Kazantzakis well. So well in fact that he won a scholarship in 1902 to study law at the University of Athens, and as might be imagined, Athens opened up Nikos’s mind hugely, with philosophy quickly becoming his most absorbing subject, with his final thesis in 1906, Friedrich Nietzsche on the Philosophy of Law and the State, winning him a place at the Sorbonne in Paris the following year.

With his future studies settled, Nikos returned to Crete. In Report to Greco, he writes:

“ I returned to Crete for the final summer of my student years. My mother I found seated in her usual place by the window which gave onto a courtyard. She was knitting socks. It was evening, and my sister had begun to water the pots of basil and marjoram. The trellis above the well was laden with bunches of fat, still-unripened, grapes.”

That little snippet from the start of Chapter 16, is a wonderfully simple and quite emotional description of the Kazantzakis home: a small prose poem that sticks with you, and no doubt with Nikos too as he began to write more seriously, to ‘mobilize words’. Eventually he completed (‘in a few days’) his first novel, Snake and Lily (published in 1906 as the Serpent and Lily)inspired, it would seem, by his passionate love for a young Irish girl visiting Crete, and is very much one with the early work of D.H. Lawrence, and none the worse for that. There must have been something in the air in both Nottingham and Crete at that time, for Nikos now lived in another world, a world between the imagination and reality: he was ‘intoxicated’ by it. But first he had to get his degree,

When he arrived at the Sorbonne in 1907 Nikos immediately fell under the influence of the French philosopher Henru Bergson who was the first to elaborate on what became known as ‘process philosophy’: that nothing is static, that all things are in motion and changing, which of course can be said of Kazantzakis’s own work, and of the man, and may help to explain why he was so very bad with dates.

He was also having a good time visiting the Paris cafes, and always the first to start shouting, as a letter to his mother and sisters in 1908 describes:

Darling Mother, Anestasia and Eleni,

…Last night I went to bed late…We’d gone to the cafe, shouting away, and the French people staring at us. I was one of the first to shout and laugh. A student friend of mine came to Paris the other day, and he didn’t know I was here. Suddenly I saw him running like mad through the crowd, shouting “Niko!” I stood still. “ Dear Fellow, you here?” he said. “ I heard you laughing from the other end of the street, and I said, No one else can laugh like that. And here you are!”

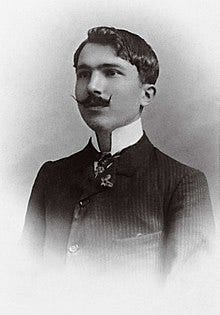

Nikos in 1904. Image: wikipedia

Nikos in 1904. Image: wikipediaWe see here the early characteristics of his most famous creation, the irrepressible Zorba, who begins and ends a host of sentences with laughter and shouting. For me, Anthony Quinn’s film portrayal of Zorba is, perhaps, how we can best imagine Nikos — albeit crossed with the quieter Alan Bates character — as an older man, but still shouting.

Nikos’s final 1909 paper at the Sorbonne was in fact an extended version of his 1906 paper, retitled Friedrich Nietzsche on the Philosophy of Right and the State. This suggests he had become more politicised in his thinking, but also busy writing fiction instead of a completely new thesis.

Upon his return to Crete his father kept a promise to Nikos that if he came home with a degree, and a good one, he would pay for him to travel the world, which was a very expensive promise to make. To help his father with his travel costs, Nikos found work translated works of philosophy for a local publisher.

He started his travels, firstly in Greece where, in 1914, at Mount Athos, he met the young poet Angelos Sikelianos. The two became great friends and continued travelling together for two years, taking in Italy and Jerusalem.

From 1922–1924 our young novelist lived in Paris and Berlin, and for a while, in Russia before, in 1932, moving to Spain. Later he would also live in Cyprus, Aegina, Egypt, Mount Sinai, Czechoslovakia and Antibes in the south of France.

In Berlin, in those years after WWI, revolution was in the air, with Hitler’s mob facing down the communists, often with extreme violence. And although he initially admired Lenin, he never became a truly committed Marxist.

Later Nikos visited the Soviet Union where he witnessed the bloody rise of Joseph Stalin, and as a result quickly became disillusioned with Soviet-style communism. Kazantzakis now adopted a “… more universalist ideology...” which was confirmed in 1926, when working as a journalist, he [as did Ernest Hemingway], managed to get an interview with the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini. He wasn’t impressed and saw trouble ahead.

During World War II Kazantzakis lived mainly in Athens, where, with the Greek classical scholar, Professor Ioannis Kakridis, he translated, into modern Greek, Homer’s Iliad.

After World War II Kazantzakis created a small left wing political party (just about everyone else was doing the same), becoming a Minister in the new Greek government. Sadly, his temperament was not that of a politician. He resigned his post in 1946.

Once free of politics, he and Helen travelled to England where they met Michael Cacoyannis, a Greek film student who impressed the couple with his ideas about film making: so much so that when the film of Zorba the Greek was in pre-production Helen requested that Cacoyannis be the director. In 1964 the finished film garnered three Academy Awards.

In 1911 Kazantzakis had married the feminist poet and playwright, Galatea Alexiou, a young woman with extreme left wing views. The newly married couple wrote articles and pamphlets together under the names of ‘Petros and Petroula Psilorite.’ And although they were both Cretans, it would seem they were not well matched; eventually divorcing in 1926.

Nikos married Eleni Samiou in 1945, and, not unlike Hemingway with Mary, it was Helen with whom Nikos found love, and with a woman who shared his beliefs, becoming a champion of his work, as most poignantly expressed in her 1968 biography of her husband, Nikos Kazantzakis — A Biography Based on His Letters (translated by Amy Mims), which, as previously suggested, is a passionate gospel that must be read to even try and understand the man, and the writer, that was Nikos Kazantzakis, and how he and Helen were effected by the murderous Nazi occupation of Greece and Crete, as the following describes:

“ Whole villages were reduced to a heap of cinders. Helpless old men, women, children were murdered in cold blood. In their memoirs, English secret agents have described the affliction of the Greek people and at the same time their determination to achieve their own liberation in every possible way — till the day when these same people were subjected to the English bombs and mortars come to kill them in their own capital...”

This angry response from Helen is understandable of course, and Kazantzakis’s own response to her as he correctly foresaw “…the dangerous turn our history was about to take…”, namely civil war.

But then Nikos had to go into hiding to avoid a visit by the Nazi SS, who had already taken prisoner 80,000 Jews across Greece, although 20,000 had been safely hidden by the partisans. Kazantzakis would not have survived the war had he been found. Crucifixion.

Helen’s description of those years during WWII is second to none, and a must read for all students of Greek history.

Helen was a noted writer before she met Kazantzakis; but her work comes to a peak in her biography of her husband, especially when describing her love for Nikos and their life together.

But it is Nikos’s Report to Greco that is at the heart of this piece, which is an extraordinary rich novel of power, love, death and rebirth.

In 1957 Kazantzakis came close to winning the Nobel Prize for Literature, but lost out to Albert Camus by one vote. Camus said that Kazantzakis deserved the honour “a hundred times more” than himself.

Late in 1957, even though suffering from leukemia, Nikos set out on one last trip to China and Japan. He fell ill on his return flight, which was transferred he was transferred to Germany, where he died.

Helen Kazantzakis died as a result of a road accident in 1989.

Nikos Kazantzakis is buried on the city wall of Heraklion.

“I hope for nothing. I fear nothing. I am free.”

Bibliography: Report to Greco, Zorba the Greek, Christ Recrucified, and Freedom and Death; Helen Kazantzakis’ Nikos Kazantzakis: A Biography (Simon & Schuster 1968), and two extremely well written and detailed Wikipedia entries which stand the test. But I must acknowledge Kazantzakis Publications, who have an abundance of information about NK.