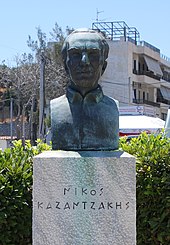

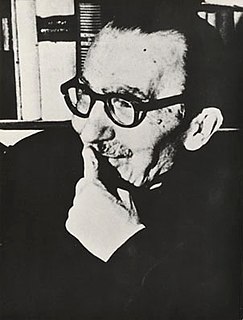

니코스 카잔차키스

| 이 문서는 영어 위키백과의 Nikos Kazantzakis 문서를 번역하여 문서의 내용을 확장할 필요가 있습니다. |

Νίκος Καζαντζάκης | |

|---|---|

| |

작가 정보 | |

| 출생 | 1883년 2월 18일 |

| 사망 | 1957년 10월 26일 |

| 직업 | 소설가, 시인, 정치가 |

| 국적 | |

| 배우자 | 갈라테아 알렉시우(1926년 이혼), 엘레니 사미우(1945년 결혼) |

주요 작품 | |

| 《그리스인 조르바》, 《미할리스 대장》, 《전쟁과 신부》 외 | |

니코스 카잔자키스(그리스어: Νίκος Καζαντζάκης, 영어: Nikos Kazantzakis, 1883년 2월 18일 ~ 1957년 10월 26일)는 현대 그리스 문학을 대표하는 소설가이자 시인이다. 동 서양 사이에 위치한 그리스의 지형적 특성과 터키 지배하의 기독교인 박해 겪으며 어린시절을 보낸 그는 이런 경험을 바탕으로 그리스 민족주의 성향의 글을 썼으며, 나중에는 베르그송과 니체를 접하면서 한계에 도전하는 투쟁적 인간상을 바탕으로 글을 썼다. 소설 <십자가에 못박히는 그리스도>로 세계적인 명성을 얻었는데, 시적인 문체의 난해한 작품을 남겼다.[1]

생애와 문학세계[편집]

태어나서 제1차 세계 대전까지[편집]

1883년 오스만 제국 치하 크레타 섬의 이라클리오에서 태어났다. 아버지 미할리스 카잔자키스 곡물과 포도주 중개상으로 중산층에 속했다. 그는 크리티 섬에서 중등 교육을 마치고 1902년 아테네 대학교에서는 법학을 공부했으며, 재학 도중 수필 《병든 시대》와 소설 《뱀과 백합》을 출간하기도 했으며 희곡도 쓰기도 했다. 1907년에는 파리로 유학했으며 베르그송과 니체 철학을 공부했다. 1911년 그리스로 돌아와 갈라테아 알렉시우와 결혼했으며 제1차 발칸 전쟁이 발발하자 육군에 자원 입대하여 베니젤로스 총리 비서실에서 복무하기도 했다. 1917년 고향 크리티 섬에 돌아와 후에 그리스인 조르바의 주인공 알렉시스 조르바의 실제 인물인 조르바와 함스 갈탄 채굴 및 벌목 사업을 했었으며, 이것이 소설 그리스인 조르바로 발전하였다. 1919년 베니젤로스 총리에 의해 공공복지부 장관으로 임명되어 1차대전 평화 협상에 참가하기도 했으나 이듬해 베니젤로스의 자유당이 선거에 패배하여 장관직을 사임하고 파리로 갔으며 그 후 유럽을 여행했다.

제1차 세계 대전에서 죽을 때까지[편집]

공산주의 경도[편집]

빈에 체재하는 도중 1922년 그리스 터키 간 전쟁에서 그리스가 패배했다는 소식을 듣자 이전 민족주의를 버리고 공산주의 성향을 나타내기도 했으며 소비에트 연방에 대한 동경으로 러시아 어 공부를 하기도 했다. 1925년, 1928년에는 공산주의 활동으로 인해 정부로부터 탄압을 받기도 했으나 루사코프 사건이 발생한 이후 소비에트 체재에 대해 회의적인 입장으로 변했다.

제2차 세계대전과 내전[편집]

1926년 갈라테아 알렉시우와 이혼했으며 이후 프랑스어와 그리스어로 작품활동을 계속했다. 1940년 이탈리아 무솔리니 정권이 그리스를 침공하자, 일시적으로 민족주의 쪽으로 돌아서기도 했으며 1944년 독일군이 그리스에서 철수하자 아테네로 돌아왔다. 그때 12월 사태로 알려진 내전을 눈으로 직접 목격했다.

사회주의 운동과 결혼[편집]

이후 정치로 다시 뛰어들겠다는 결심을 하고 그리스 사회당의 지도자가 되었으며, 소풀리스 연립정부의 정무 장관으로 임명된다. 1946년 정무 장관직을 사임했다. 그해, 그리스 작가 협회는 카잔차키스와 앙겔로스 시겔리아노스를 노벨 문학상 후보로 추천하기도 했다. 그리고 오랜 동반자였던 엘레니 사미우와 결혼했다.

교회의 박해[편집]

1953년 소설 《미할리스 대장》이 발간되자 그리스 정교회는 맹렬히 카잔자키를 비난했으며 이듬해 로마 가톨릭 교회도 《최후의 유혹》을 금서 목록에 올리기도 했다. 이후 카잔차의킷소설은 그리스에서 일시적으로 출간되지 않기도 했다. 카잔차키자교킷 테르툴리아누스(터툴리안)의 말을 인용해 로마 가톨릭 교회와 그리스 정교회에 자신의 입장을 옹호했다. 1955년에는 그리스 왕실의 도움으로 《최후의 유혹》이 그리스에서 발간되었다.

별세[편집]

1956년에는 국제 평화상을 수상하기도 했다. 1957년 중국 정부의 초청으로 중국을 여행했으며 일본을 경유해 돌아오는 도중 백혈병 증세를 보여 급히 독일의 병원으로 옮겨졌다. 이때 알베르트 슈바이처 박사와 만나기도 했다. 고비를 넘겼으나 독감에 걸려 10월 26일 독일에서 사망했다.

문학세계[편집]

불교의 영향을 받기도 했으며 베르그송과 니체의 영향을 받아 인간의 자유에 대해서 탐구, 한계에 저항하는 투쟁적 인간상을 부르짖었다. 대다수의 작품에서 줄거리 전개보다는 사상의 흐름을 강조했으며, 1951년과 1956년, 노벨 문학상 후보로 지명되어 천재성을 인정받았다. 대표작으로는 후에 마틴 스코세이지 감독에 의해 영화로 만들어진《최후의 유혹》과 《그리스인 조르바》,《오디세이아》(시)가 있다. 이중 소설 《미할리스 대장》과 《최후의 유혹》은 그리스 정교회와 로마 가톨릭 으로부터 신성모독을 이유로 파문당할 만큼 당시 세계에 큰 영향을 끼쳤다. 하지만 니코스 카찬자키스는 교회로부터 반기독교도로 매도되는 탄압을 받았어도, 평생 자유와 하느님을 사랑한 그리스도인이었다.

극작으로 1946년에 <카포디스토리아스>, 1959년에는 <배교자(背敎者) 율리우스>, 1962년에는 <메리사>가 각기 상연되었다.

남긴 말[편집]

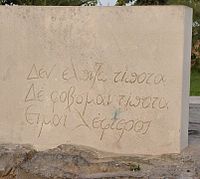

생전에 미리 써놓은 묘비명에서 그는 다음과 같이 말했다.

| “ | Δεν ελπίζω τίποτα. Δε φοβούμαι τίποτα. Είμαι λέφτερος 나는 아무것도 바라지 않는다. 나는 아무것도 두려워하지 않는다. 나는 자유인이다. | ” |

저작[편집]

소설[편집]

- 《향연》

- 《토다 라바》

- 《돌의 정원》 (1936년)

- 《알렉산드로스 대왕》 (1940년)

- 《크노소스 궁전》 (1940년)

- 《그리스인 조르바》(Βίος και πολιτεία του Αλέξη Ζορμπά) (1943년)

- 《수난》

- 《미할리스 대장》(Ο καπετάν Μιχάλης) (1953년)

- 《최후의 유혹》(Ο τελευταίος πειρασμός) (1951년)

- 《성자 프란체스코》

- 《전쟁과 신부》

여행기[편집]

- 《스페인 기행》

- 《지중해 기행》

- 《러시아 기행》 (1940년)

- 《모레아 기행》

- 《영국 기행》

- 《일본, 중국 기행》

서사시, 희곡, 자서전[편집]

- 《오디세이아》(Οδύσσεια) (1938년)

- 《붓다》

- 《소돔과 고모라》

- 《영혼의 자서전》

- 《카잔자스의 편지》

출처[편집]

각주[편집]

| 위키미디어 공용에 관련된 미디어 분류가 있습니다. |

- ↑ 《글로벌 세계대백과사전》

일어

니코스 카잔자키스

니코스 카잔자키스 ( Νίκος Καζαντζάκης , 1883년 2월 18일 - 1957년 10월 26일 ) 는 그리스 소설가 , 시인 , 정치인 . 이교도인 터키인 에게 지배되어 곧 독립하는 소박하고 묵직한 그리스인 과 그 역사를 꿰뚫고 또 한 사람으로 고민 하는 예수 그리스도 라는 참신한 그리스도상을 그려냈다. 대표작 『그 남자 졸바』, 『그리스도는 다시 십자가에 못박힌다』, 『마지막 유혹』, 『오디시아』, 『금욕』 등. 프랑스 에서 본인의 서명에 근거하여 니코스 카잔차키 로 기록되는 경우도 있다.

약력 [ 편집 ]

카잔자키스는 크레타 북부의 이라클리오 (칸디아) 농가에서 태어났다. 1897년 , 당시 크레타 섬의 지배자인 오스만 제국 에 대한 그리스인의 반란이 격화되면, 일가는 어려움을 피해 낙소스 섬 으로 피난했다. 1906년 아테네 대학 법학부 를 우수한 성적으로 졸업한다. 재학중부터 아테네 의 신문사에서 칼럼을 담당하고 있었지만, 1906년에는 처녀작 '뱀과 백합'을 발표, 1907년에는 희곡 '새벽'이 상연되고 있다. 그 해에 그는 파리 로 가서 앙리 버크슨 하에서 철학 을 배웁니다. 또 이 프랑스에서의 유학기에 프리드리히 니체 의 철학을 만나 강한 영향을 받는다. 1911년에는 학우인 갈라티아 알렉시우와 결혼(1926년 이혼)했다.

1912년 제 1차 발칸 전쟁 이 발발하자 지원병 으로 종군했다. 1917년 요르고스 졸바스라는 남자와 공동으로 광산업 에 손을 대고 실패한다. 이때의 경험이 『그 남자 졸바』의 기초가 되고 있다. 1919년 그리스 후생성의 국장으로서, 카프카스 와 남 러시아 에 있는 약 15만명의 폰토스인 을 포함한 그리스인 난민 의 귀환 사업에 임해 성공한다.

1922년 , 빈 에서 불교 연구를 한다. 그 후 독일 로 옮겨 공산주의 와 만난다. 제1차 세계대전 이후 황폐한 유럽 가운데 종교에 빠지지 않는 것을 느낀 그는 공산주의에 희망을 찾아내려고 했다. 그러나, 1925년 , 1927년 의 2회에 걸쳐 방문해, 소련 에 있어서의 공산주의를 실제로 보는 것으로, 마르크스주의 의 한계를 깨닫는다. 이때의 체험을 바탕으로 1930년 프랑스어 로 소설 '토다 라바'를 집필하고 있다. 1927년은 소련 정부의 빈객으로서 방문하고 있지만, 이때, 똑같이 초대되고 있던 아키타 우작 과 동행한 것이 아키타의 일기에 기재되어 있다 [1] .

1938년 , 12년의 세월에 걸쳐 작성한 서사시 「오디시아」를 발표한다. 1941년 부터 1944년 에 걸쳐 제2차 세계대전 에서 독일이 그리스를 점령한 기간 중 카잔자키스는 에이나섬 에서 '그 남자 졸바' 등의 집필을 한다.

1945년 테 미스트 크리스 소프리스 내각의 무임소상 으로서 일시입각함과 동시에 엘레네 사미오스와 재혼했다. 1946년 에 대표작 『그 남자 졸바』를 발표, 유네스코 의 고전 번역부장을 근무한다. 올해 이후 사망할 때까지 그리스로 돌아오지 않았다.

1948년 이후 프랑스 의 앙티브 에 살고 있다. 이 시기에 '그리스도는 다시 십자가에 못박힌다', '마지막 유혹' 등의 후기 대표작이라고도 할 소설을 발표하고 있다. 1957년 독일 프라이부르크 에서 사망. 시신은 크레타 섬에 매장되었다.

공산주의 보다 정치활동을 한 것, 소설 내에서 참신한 그리스도상을 제시하거나 그리스 정교회 의 부정적인 측면을 그렸기 때문에 당시 그리스 국내에서도 평가가 나뉘었다. 소설 '마지막 유혹'은 가톨릭 교회 에서 금서 취급을 받았다. 또 1945년 그리스 작가 연맹은 카잔자키스를 노벨 문학상 후보로 추천했지만 정부의 방해로 실현되지 않았다. 사실, 1947년 과 1950년 에는 후보로 지명된 것으로 밝혀졌다 [2] . 지난 1957년 에는 알베르 카뮤 에게 1표 차이로 수상을 놓쳤지만, 이에 대해 카뮤는 나중에 “카잔자키스 쪽이 100배 이상이나 노벨 문학상을 수상하기에 어울렸다”고 말했다 . 있다.

여행을 좋아하고, 평생에 걸쳐 세계 각지를 방문하고 있는 카잔자키스는 1935년 에 일본 과 중국 을 방문해, 1938년 에는 여행기『일본・중국』( Ταξιδεύοντας. Ιαπωνία-Κίνα )을 저술하고 있다.

주요 저작 [ 편집 ]

- 1906년 「뱀과 백합」(Όφις και Κρίνο) 其原哲也

- 1922년 『향연』(Συμπόσιον) 후쿠다 코 우유

- 1930년 「러시아 문학사」

- 1936년 「돌의 정원」( Le Jardin des rochers )

- 시미즈 시게루 『돌의 정원』 1978년, 요미우리 신문사, ISBN 9784643724202 .

- 1938년 「일본 중국 여행기」(Ταξιδεύοντας: Ιαπωνία-Κίνα) 후지시타 유키코

- 1938년 『오디시아』( Οδύσσεια , The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel )

- 1943년 『그 남자 졸바』( Βίος και πολιτεία του Αλέξη Ζορμπά , Zorba the Greek )

- 아키야마 켄역 『그 남자 졸바』 1967년:1996년, 항문사, ISBN 9784770402103 (제4판)

- 1944년 ' 금욕 ' (Ασκητική, Salvatores Dei, The Saviors of God ) 후쿠다 경작

- 1948년 ' 그리스도는 다시 십자가에 못 박힌다 ' ( Ο Χριστός ξανασταυρώνεται , Christ Recrucified )

- 후쿠다 치즈코 번역 『대역

- 후쿠다 치즈코·카타야마 노리코 번역 『그리스도는 다시 십자가에』( 2 분권 )

- 고다마 조역 『다시 십자가에 못 박히는 그리스도』 2003년, 신풍사, ISBN 9784797432879

- 후지시타 유키코 · 타지마 요시코 역

- 1951년 ' 마지막 유혹 ' ( Ο τελευταίος πειρασμός , The Last Temptation of Christ )

- 고다마 조역 『그리스도 마지막 마음』 1982년, 항문사, ISBN 9784770404985

- 1953년 『형제 살해』(Οι Αδελφοφάδες)

- 이노우에 등역 『형제 살인』 1978년, 요미우리 신문사, ISBN 9784643724608

- 1956년 『아시지의 빈자』( Ο Φτωχούλης του Θεού )

- 시미즈 시게역 『아시지의 빈자』 1981년:1997년, 미스즈 서방, ISBN 9784622049166 (신장판)

영화화된 작품 [ 편집 ]

지금까지 3개의 카잔자키스의 소설이 영화화되고 있다. '그리스도는 다시 십자가에 못 박힌다'는 붉은 사냥 으로 할리우드 를 쫓긴 줄즈 다신 감독에 의해 ' 숙명 '( Celui qui doit mourir )으로 1957년 프랑스에서 영화화되었다. '그 남자 졸바'는 1964년 그리스 출신의 마이클 카코야니스 감독에 의해 ' 그 남자 졸바 '( Zorba the Greek )로 영화화되어 1965년에 3개의 오스카 를 획득했다. 호방이면서 매력적인 졸바를 앤서니 퀸 이 연기하고 있다. 마틴 스코세시 감독에 의한 ' 마지막 유혹 '( The Last Temptation of Christ )은 일단 제작 중단의 우수를 만나면서도 구상으로부터 6년의 세월을 들여 1988년에 영화화되었다. 그러나 상영 시에는 가톨릭계 단체에 의한 반대 운동을 초래하게 되었다.

참고 문헌 [ 편집 ]

- Γιώργος Ανεμογιάννης, Νίκος Καζαντζάκης 1883-1957 Εικονογραφημένη Βιογραφία(Τρίτη Έκδοση), Έκδοση ιδρύματος <<Μουσείο Καζαντζάκη>>, Θεσσαλονίκη, 2007 ISBN 960-90186-0-2

- Καζαντζάκη, Ελένη Ν. (1998). Νίκος Καζαντζάκης, ο ασυμβίβαστος: Βιογραφία βασισμένη σε ανέκδοτα γράμματα και κείμενά του . επιμέλεια: Πάτροκλος Σταύρου. Αθήνα: Εκδόσεις Καζαντζάκη. ISBN 9780007948116

- Καζαντζάκης, Νίκος; Πρεβελάκης , Παντελής (1984). Τετρακόσια γράμματα του Καζαντζάκη

각주 [ 편집 ]

- ^ https://www.greecejapan.com/japanesestudies/o-nikos-kazantzakis-kai-i-neoelliniki-logotexnia-ston-tomea-tis-iaponologias/

- ↑ Nomination Database The Nomination Database for the Nobel Prize in Literature, 1901-1950

외부 링크 [ 편집 ]

- Nikos Kazantzakis Museum (그리스어, 영어, 프랑스어, 독일어)

- 카잔 자키스 친구 모임 일본 지부 HP

Nikos Kazantzakis - Wikipedia:

Nikos Kazantzakis

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (March 2012) |

Nikos Kazantzakis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 2 March 1883 Kandiye, Crete, Ottoman Empire (now Heraklion, Greece) |

| Died | 26 October 1957 (aged 74) Freiburg im Breisgau, West Germany (now Germany) |

| Occupation | Poet, novelist, essayist, travel writer, philosopher, playwright, journalist, translator |

| Nationality | Greek |

| Education | University of Athens (1902–1906; J.D., 1906)[1] University of Paris (1907–1909; DrE, 1909)[1] |

| Signature |  |

Nikos Kazantzakis (Greek: Νίκος Καζαντζάκης [ˈnikos kazanˈd͡zacis]; 2 March (OS 18 February) 1883[2] – 26 October 1957) was a Greek writer. Widely considered a giant of modern Greek literature, he was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature nine times.[3]

Kazantzakis' novels included Zorba the Greek (published 1946 as Life and Times of Alexis Zorbas), Christ Recrucified (1948), Captain Michalis (1950, translated Freedom or Death), and The Last Temptation of Christ (1955). He also wrote plays, travel books, memoirs and philosophical essays such as The Saviors of God: Spiritual Exercises. His fame spread in the English-speaking world due to cinematic adaptations of Zorba the Greek (1964) and The Last Temptation of Christ (1988).

He translated also a number of notable works into Modern Greek, such as the Divine Comedy, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, On the Origin of Species, the Iliad and the Odyssey.[4]

Biography[edit]

When Kazantzakis was born in 1883 in Kandiye, now Heraklion, Crete had not yet joined the modern Greek state (which had been established in 1832), and was still under the rule of the Ottoman Empire. From 1902 to 1906 Kazantzakis studied law at the University of Athens: his 1906 Juris Doctor thesis title was Ο Φρειδερίκος Νίτσε εν τη φιλοσοφία του δικαίου και της πολιτείας[1] ("Friedrich Nietzsche on the Philosophy of Law and the State"). Then he went to the Sorbonne in 1907 to study philosophy. There he fell under the influence of Henri Bergson. His 1909 doctoral dissertation at the Sorbonne was a reworked version of his 1906 dissertation under the title Friedrich Nietzsche dans la philosophie du droit et de la cité ("Friedrich Nietzsche on the Philosophy of Right and the State").[1] Upon his return to Greece, he began translating works of philosophy. In 1914 he met Angelos Sikelianos. Together they travelled for two years in places where Greek Orthodox Christian culture flourished, largely influenced by the enthusiastic nationalism of Sikelianos.

Kazantzakis married Galatea Alexiou in 1911; they divorced in 1926. Kazantzakis met Eleni Samiou in 1924.[5] They began a romantic relationship in 1928, though they were not married until 1945. Samiou helped Kazantzakis with his work, typing drafts, accompanying him on his travels, and managing his business affairs.[5] They were married until his death in 1957. Samiou died in 2004.[6]

Between 1922 and his death in 1957, he sojourned in Paris and Berlin (from 1922 to 1924), Italy, Russia (in 1925), Spain (in 1932), and then later in Cyprus, Aegina, Egypt, Mount Sinai, Czechoslovakia, Nice (he later bought a villa in nearby Antibes, in the Old Town section near the famed seawall), China, and Japan.

While in Berlin, where the political situation was explosive, Kazantzakis discovered communism and became an admirer of Vladimir Lenin. He never became a committed communist, but visited the Soviet Union and stayed with the Left Opposition politician and writer Victor Serge. He witnessed the rise of Joseph Stalin, and became disillusioned with Soviet-style communism. Around this time, his earlier nationalist beliefs were gradually replaced by a more universalist ideology. As a journalist in 1926 he got interviews from Miguel Primo de Rivera and the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini.

Death[edit]

During WWII he was in Athens and translated the Iliad, together with the philologist Ioannis Kakridis. In 1945, he became the leader of a small party on the non-communist left, and entered the Greek government as Minister without Portfolio. He resigned this post the following year. In 1946, The Society of Greek Writers recommended that Kazantzakis and Angelos Sikelianos be awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. In 1957, he lost the Prize to Albert Camus by one vote. Camus later said that Kazantzakis deserved the honour "a hundred times more" than himself.[7] In total Kazantzakis was nominated in nine different years.[8] Late in 1957, even though suffering from leukemia, he set out on one last trip to China and Japan. Falling ill on his return flight, he was transferred to Freiburg, Germany, where he died. He is buried at the highest point of the Walls of Heraklion, the Martinengo Bastion,[9] looking out over the mountains and sea of Crete. His epitaph reads "I hope for nothing. I fear nothing. I am free." (Δεν ελπίζω τίποτα. Δε φοβούμαι τίποτα. Είμαι λέφτερος.) Kazantzakis developed this famously pithy phrasing of the philosophical ideal of cynicism, which dates back to at least the second century AD.[10]

The 50th anniversary of the death of Nikos Kazantzakis was selected as main motif for a high-value euro collectors' coin; the €10 Greek Nikos Kazantzakis commemorative coin, minted in 2007. His image is on the obverse of the coin, while the reverse carries the National Emblem of Greece with his signature.

Literary work[edit]

Kazantzakis' first published work was the 1906 narrative, Serpent and Lily (Όφις και Κρίνο), which he signed with the pen name Karma Nirvami. In 1907 Kazantzakis went to Paris for his graduate studies and was deeply influenced by the philosophy of Henri Bergson, primarily the idea that a true understanding of the world comes from the combination of intuition, personal experience, and rational thought.[11] The theme of rationalism mixed with irrationality later became central to many of Kazantzakis' later stories, characters, and personal philosophies. Later, in 1909, he wrote a one-act play titled Comedy, which was filled with existential themes, predating the post-World War II existentialist movement in Europe spearheaded by writers like Jean-Paul Sartre and Camus. After completing his studies in Paris, he wrote the tragedy, "The Master Builder" (Ο Πρωτομάστορας), based on a popular Greek folkloric myth.

Through the next several decades, from the 1910s through the 1930s, Kazantzakis traveled around Greece, much of Europe, northern Africa, and to several countries in Asia. Countries he visited include: Germany, Italy, France, The Netherlands, Romania, Egypt, Russia, Japan, and China, among others. These journeys put Kazantzakis in contact with different philosophies, ideologies, lifestyles, and people, all of which influenced him and his writings.[12] Kazantzakis would often write about his influences in letters to friends, citing Sigmund Freud, the philosophy of Nietzsche, Buddhist theology, and communist ideology and major influences. While he continued to travel later in life, the bulk of his travel writing came from this time period.

Kazantzakis began writing The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel in 1924, and completed it in 1938 after fourteen years of writing and revision.[12] The poem follows the hero of Homer's Odyssey, Odysseus, as he undertakes a final journey after the end of the original poem. Following the structure of Homer's Odyssey, it is divided into 24 rhapsodies and consists of 33,333 lines.[11] While Kazantzakis felt this poem held his cumulative wisdom and experience, and that it was his greatest literary experience, critics were split, "some praised it as an unprecedented epic, [while] many simply viewed it as a hybristic act," with many scholars still being split to this day.[12] A common criticism of The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel was aimed at Kazantzakis' over-reliance on flowery and metaphorical verse, a criticism that is also aimed at his works of fiction.[11]

Many of Kazantzakis' most famous novels were published between 1940 and 1961, including Zorba the Greek (1946), Christ Recrucified (1948), Captain Michalis (1953), The Last Temptation of Christ (1955), and Report to Greco (1961).

Scholar Peter Bien argues that each story explores different aspects of post-World War II Greek culture such as religion, nationalism, political beliefs, the Greek Civil War, gender roles, immigration, and general cultural practices and beliefs.[11] These works also explore what Kazantzakis believed to be the unique physical and spiritual location of Greece, a nation that belongs to neither the East nor the West, an idea he put forth in many of his letters to friends.[12] As the scholar Peter Bien argued, "Kazantzakis viewed Greece's special mission as the reconciliation of Eastern instinct with Western reason," echoing the Bergsonian themes that balance logic against emotion found in many of Kazantzakis' novels.[11]

Two of these works of fiction, Zorba the Greek and The Last Temptation of Christ had major motion picture adaptations in 1964 and 1988 respectively.

Language and use of Demotic Greek[edit]

During the time when Kazantzakis was writing his novels, poems, and plays, the majority of "serious" Greek artistic work was written in Katharevousa, a "pure" form of the Greek language that was created to bridge Ancient Greek with Modern, Demotic Greek, and to "purify" Demotic Greek. The use of Demotic, among writers, gradually started to gain the upper hand only in the turn of the 20th century, under the influence of the New Athenian School (or Palamian).

In his letters to friends and correspondents, Kazantzakis wrote that he chose to write in Demotic Greek to capture the spirit of the people, and to make his writing resonate with the common Greek citizen.[11] Moreover, he wanted to prove that the common spoken language of Greek was able to produce artistic, literary works. Or, in his own words, "Why not show off all the possibilities of demotic Greek?"[11] Furthermore, Kazantzakis felt that it was important to record the vernacular of the everyday person, including Greek peasants, and often tried to include expressions, metaphors, and idioms he would hear while traveling throughout Greece, and incorporate them into his writing for posterity.[11][12] At the time of writing, some scholars and critics condemned his work because it was not written in Katharevousa, while others praised it precisely because it was written in Demotic Greek.

Several critics have argued that Kazantzakis' writing was too flowery, filled with obscure metaphors, and difficult to read, despite the fact that his works were written in Demotic Greek. Kazantzakis scholar Peter Bien argues that the metaphors and language Kazantzakis used were taken directly from the peasants he encountered when traveling Greece.[11] Bien asserts that, since Kazantzakis was trying to preserve the language of the people, he used their local metaphors and phrases to give his narrative an air of authenticity and preserve these phrases so that they were not lost.[11]

Socialism[edit]

Throughout his life, Kazantzakis reiterated his belief that "only socialism as the goal and democracy as the means" could provide an equitable solution to the "frightfully urgent problems of the age in which we are living."[13] He saw the need for socialist parties throughout the world to put aside their bickering and unite so that the program of "socialist democracy" could prevail not just in Greece, but throughout the civilized world.[13] He described socialism as a social system which "does not permit the exploitation of one person by another" and that "must guarantee every freedom."[13]

Kazantzakis was anathema to the right-wing in Greece both before and after World War II. The right waged war against his books and called him "immoral" and a "Bolshevik troublemaker" and accused him of being a "Russian agent".[14] He was also distrusted by the Greek and Russian Communist parties as a "bourgeois" thinker.[14] However, upon his death in 1957, he was honored by the Chinese Communist party as a "great writer" and "devotee of peace."[14] Following the war, he was temporarily leader of a minor Greek leftist party, while in 1945 he was, among others, a founding member of the Greek-Soviet friendship union.

Religious beliefs and relationship with the Greek Orthodox Church[edit]

While Kazantzakis was deeply spiritual, he often discussed his struggle with religious faith, specifically his Greek Orthodoxy.[15] Baptized Greek Orthodox as a child, he was fascinated by the lives of saints from a young age. As a young man he took a month long trip to Mount Athos, a major spiritual center for Greek Orthodoxy. Most critics and scholars of Kazantzakis agree that the struggle to find truth in religion and spirituality was central to a great deal of his works, and that some novels, like The Last Temptation of Christ and Christ Recrucified focus completely on questioning Christian morals and values.[16] As he traveled Europe, he was influenced by various philosophers, cultures, and religions, like Buddhism, causing him to question his Christian beliefs.[17] While never claiming to be an atheist, his public questioning and critique of the most fundamental Christian values put him at odds with some in the Greek Orthodox church, and many of his critics.[16] Scholars theorize that Kazantzakis' difficult relationship with many members of the clergy, and the more religiously conservative literary critics, came from his questioning. In his book, Broken Hallelujah: Nikos Kazantzakis and Christian Theology, author Darren Middleton theorizes that, "Where the majority of Christian writers focus on God's immutability, Jesus' deity, and our salvation through God's grace, Kazantzakis emphasized divine mutability, Jesus' humanity, and God's own redemption through our effort," highlighting Kazantzakis' uncommon interpretation of traditional Orthodox Christian beliefs.[18] Many Orthodox Church clergy condemned Kazantzakis' work and a campaign was started to excommunicate him. His reply was: "You gave me a curse, Holy fathers, I give you a blessing: may your conscience be as clear as mine and may you be as moral and religious as I" (Greek: "Μου δώσατε μια κατάρα, Άγιοι πατέρες, σας δίνω κι εγώ μια ευχή: Σας εύχομαι να ‘ναι η συνείδηση σας τόσο καθαρή, όσο είναι η δική μου και να ‘στε τόσο ηθικοί και θρήσκοι όσο είμαι εγώ"). While the excommunication was rejected by the top leadership of the Orthodox Church, it became emblematic of the persistent disapprobation from many Christian authorities for his political and religious views.

Modern scholarship tends to dismiss the idea that Kazantzakis was being sacrilegious or blasphemous with the content of his novels and beliefs.[19] These scholars argue that, if anything, Kazantzakis was acting in accordance to a long tradition of Christians who publicly struggled with their faith, and grew a stronger and more personal connection to God through their doubt.[16] Moreover, scholars like Darren J. N. Middleton argue that Kazantzakis' interpretation of the Christian faith predated the more modern, personalized interpretation of Christianity that has become popular in the years after Kazantzakis' death.[18]

The Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras, the leader of the Orthodox Church, declared in 1961 in Heraklion: “Kazantzakis is a great man and his works grace the Patriarchal library.”

Bibliography of English translations[edit]

Translations of The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel, in whole or in part[edit]

- The Odyssey [Selections from], partial translation in prose by Kimon Friar, Wake 12 (1953), pp. 58–65.

- The Odyssey, excerpt translated by Kimon Friar, Chicago Review 8, No. 2 (Spring/Summer 1954), pp. 12–18.

- "The Return of Odysseus", partial translation by Kimon Friar, The Atlantic Monthly 195, No. 6 (June 1955), pp. 110–112.

- The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel, a full verse-translation by Kimon Friar, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1958; London: Secker and Warburg, 1958.

- "Death, the Ant", from The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel, Book XV, 829–63, translated by Kimon Friar, The Charioteer, No. 1 (Summer 1960), p. 39.

Travel books[edit]

- Spain, translated by Amy Mims, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1963.

- Japan, China, translated by George C. Pappageotes, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1963; published in the United Kingdom as Travels in China & Japan, Oxford: Bruno Cassirer, 1964; London: Faber and Faber, 1964.

- England, translated by Amy Mims, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1965; Oxford, Bruno Cassirer, 1965.

- Journey to Morea, translated by F. A. Reed, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1965; published in the United Kingdom as Travels in Greece, Journey to Morea, Oxford, Bruno Cassirer, 1966.

- Journeying: Travels in Italy, Egypt, Sinai, Jerusalem and Cyprus, translated by Themi Vasils and Theodora Vasils, Boston and Toronto: Little, Brown and Company, 1975; San Francisco: Creative Arts Books Co., 1984.

- Russia, translated by A. Maskaleris and M. Antonakis, Creative Arts Books Co, 1989.

Novels[edit]

- Zorba the Greek, translated by Carl Wildman, London, John Lehmann, 1952; New York, Simon & Schuster, 1953; Oxford, Bruno Cassirer, 1959; London & Boston: Faber and Faber, 1961 and New York: Ballantine Books, 1964.

- The Greek Passion, translated by Jonathan Griffin, New York, Simon & Schuster, 1954; New York, Ballantine Books, 1965; published in the United Kingdom as Christ Recrucified, Oxford: Bruno Cassirer, 1954; London: Faber and Faber, 1954.

- Freedom or Death, translated by Jonathan Griffin, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1954; New York: Ballantine, 1965; published in the United Kingdom as Freedom or Death, Oxford: Bruno Cassirer, 1956; London: Faber and Faber, 1956.

- The Last Temptation, translated by Peter A. Bien, New York, Simon & Schuster, 1960; New York, Bantam Books, 1961; Oxford: Bruno Cassirer, 1961; London: Faber and Faber, 1975.

- Saint Francis, translated by Peter A. Bien, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1962; published in the United Kingdom as God's Pauper: Saint Francis of Assisi, Oxford: Bruno Cassirer, 1962, 1975; London: Faber and Faber, 1975.

- The Rock Garden, translated from French (in which it was originally written) by Richard Howard, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1963.

- The Fratricides, translated by Athena Gianakas Dallas, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1964; Oxford: Bruno Cassirer, 1964.

- Toda Raba, translated from French (in which it was originally written) by Amy Mims, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1964.

- Report to Greco — see under 'Memoirs, essays and letters'

- Alexander the Great. A Novel [for children], translated by Theodora Vasils, Athens (Ohio): Ohio University Press, 1982.

- At the Palaces of Knossos. A Novel [for children], translated by Themi and Theodora Vasilis, edited by Theodora Vasilis, London: Owen, 1988. Adapted from the draft typewritten manuscript.

- Father Yanaros [from the novel The Fratricides], translated by Theodore Sampson, in Modern Greek Short Stories, Vol. 1, edited by Kyr. Delopoulos, Athens: Kathimerini Publications, 1980.

- Serpent and Lily, translated by Theodora Vasils, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980.

Plays[edit]

- Julian the Apostate: First staged in Paris, 1948.

- Three Plays: Melissa, Kouros, Christopher Columbus, translated by Athena Gianakas-Dallas, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1969.

- Christopher Columbus, translated by Athena Gianakas-Dallas, Kentfield (CA): Allen Press, 1972. Edition limited to 140 copies.

- From Odysseus, A Drama, partial translation by M. Byron Raizis, "The Literary Review" 16, No. 3 (Spring 1973), p. 352.

- Comedy: A Tragedy in One Act, translated by Kimon Friar, "The Literary Review" 18, No. 4 (Summer 1975), pp. 417–454 {61}.

- Sodom and Gomorrah, A Play, translated by Kimon Friar, "The Literary Review" 19, No. 2 (Winter 1976), pp. 122–256 (62).

- Two plays: Sodom and Gomorrah and Comedy: A Tragedy in One Act, translated by Kimon Friar, Minneapolis: North Central Publishing Co., 1982.

- Buddha, translated by Kimon Friar and Athena Dallas-Damis, San Diego (CA): Avant Books, 1983.

Memoirs, essays and letters[edit]

- The Saviors of God: Spiritual Exercises, translated by Kimon Friar, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1960.

- Report to Greco, translated by Peter A. Bien, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1965; Oxford: Bruno Cassirer, 1965; London: Faber and Faber, 1965; New York: Bantan Books, 1971.

- Symposium, translated by Theodora Vasils e Themi Vasils, New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1974; New York: Minerva Press, 1974.

- Friedrich Nietzsche on the Philosophy of Right and the State, translated by O. Makridis, New York: State University of NY Press, 2007.

- From The Saviors of God: Spiritual Exercises, translated by Kimon Friar, "The Charioteer", No. 1 (Summer 1960), pp. 40–51; reprinted in "The Charioteer" 22 and 23 (1980/1981), pp. 116–129 {57}.

- The Suffering God: Selected Letters to Galatea and to Papastephanou, translated by Philip Ramp and Katerina Anghelaki Rooke, New Rochelle (NY): Caratzas Brothers, 1979.

- The Angels of Cyprus, translated by Amy Mims, in Cyprus '74: Aphrodite's Other Face, edited by Emmanuel C. Casdaglis, Athens: National Bank of Greece, 1976.

- Burn Me to Ashes: An Excerpt, translated by Kimon Friar, "Greek Heritage" 1, No. 2 (Spring 1964), pp. 61–64.

- Christ (poetry), translated by Kimon Friar, "Journal of Hellenic Diaspora" (JHD) 10, No. 4 (Winter 1983), pp. 47–51 (60).

- Drama and Contemporary Man, An Essay, translated by Peter Bien, "The Literary Review" 19, No. 2 (Winter 1976), pp. 15–121 {62}.

- "He Wants to Be Free – Kill Him!" A Story, translated by Athena G. Dallas, "Greek Heritage" 1, No. 1 (Winter 1963), pp. 78–82.

- The Homeric G.B.S., "The Shaw Review" 18, No. 3 (Sept. 1975), pp. 91–92. Greek original written for a 1946 Greek language radio broadcast by BBC Overseas Service, on the occasion of George Bernard Shaw's 90th birthday.

- Hymn (Allegorical), translated by M. Byron Raizis, "Spirit" 37, No. 3 (Fall 1970), pp. 16–17.

- Two Dreams, translated by Peter Mackridge, "Omphalos" 1, No. 2 (Summer 1972), p. 3.

- Nikos Kazantzakis Pages at the Historical Museum of Crete

- Peter Bien (ed. and tr.), The Selected Letters of Nikos Kazantzakis (Princeton, PUP, 2011) (Princeton Modern Greek Studies).

Anthologies[edit]

- A Tiny Anthology of Kazantzakis. Remarks on the Drama, 1910–1957, compiled by Peter Bien, "The Literary Review" 18, No. 4 (Summer 1975), pp. 455–459 {61}.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d "Nikos Kazantzakis" at E.KE.BI / Biblionet

- ^ The Selected Letters of Nikos Kazantzakis, p. 691

- ^ "Nomination Database". www.nobelprize.org. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ^ "ΕΚΔΟΣΕΙΣ ΚΑΖΑΝΤΖΑΚΗ". www.kazantzakispublications.org. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ a b "The Return and the Odyssey".

- ^ "Eleni Samiou (1903-2004) - Find a Grave Memorial". Find a Grave.

- ^ The Philosophers' Magazine, Issues 13–20, 2001 p. 120

- ^ Nomination Database

- ^ "Nikos Kazantzakis Grave".

- ^ Σταματίου, Ελίνα (28 August 2016). ""I do not hope for anything, I am not afraid of anything, I am free" ("Δεν ελπίζω τίποτα, δεν φοβούμαι τίποτα, είμαι λέφτερος")". Celebrity Reporter.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Peter., Bien (1989). Nikos Kazantzakis, novelist. Bristol: Bristol Classical Press. ISBN 1853990337. OCLC 19353754.

- ^ a b c d e Kimon., Friar (1979). The spiritual odyssey of Nikos Kazantzakis : a talk. Stavrou, Theofanis G., 1934-, Σταύρου, Θεοφάνης Γ. 1934-. [St. Paul, Minn.]: North Central Pub. Co. ISBN 0935476008. OCLC 6314676.

- ^ a b c Bien, Peter (1989). Kazantzakis: Politics of the Spirit, Volume 2. Princeton University Press. pp. 265–266.

- ^ a b c Georgopoulos, N. (1977). "Marxism and Kazantzakis". Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies. 3: 175–200. doi:10.1179/030701377806931780. S2CID 153476520.

- ^ Owens, Lewis (1 October 1998). ""Does This One Exist?" The Unveiled Abyss of Nikos Kazantzakis". Journal of Modern Greek Studies. 16 (2): 331–348. doi:10.1353/mgs.1998.0041. ISSN 1086-3265. S2CID 143703744.

- ^ a b c Middleton, Darren J. N. (2007). Broken hallelujah : Nikos Kazantzakis and Christian theology. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739119273. OCLC 71322129.

- ^ Middleton, Darren J. N. (24 June 2010). "Nikos Kazantzakis and Process Theology: Thinking Theologically in a Relational World". Journal of Modern Greek Studies. 12 (1): 57–74. doi:10.1353/mgs.2010.0139. ISSN 1086-3265. S2CID 146450293.

- ^ a b Middleton, Darren J. N. (1 October 1998). "Kazantzakis and Christian Doctrine: Some Bridges of Understanding". Journal of Modern Greek Studies. 16 (2): 285–312. doi:10.1353/mgs.1998.0040. ISSN 1086-3265. S2CID 142993531.

- ^ Constantelos, Demetrios J. (1 October 1998). "Kazantzakis and God (review)". Journal of Modern Greek Studies. 16 (2): 357–358. doi:10.1353/mgs.1998.0029. ISSN 1086-3265. S2CID 141618698.

Further reading[edit]

- Pandelis Prevelakis, Nikos Kazantzakis and His Odyssey. A Study of the Poet and the Poem, translated from the Greek by Philip Sherrard, with a prefaction by Kimon Friar, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1961.

- Peter Bien, Nikos Kazantzakis, 1962; New York: Columbia University Press, 1972.

- Peter Bien, Nikos Kazantzakis and the Linguistic Revolution in Greek Literature, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1972.

- Peter Bien, Tempted by happiness. Kazantzakis' post-Christian Christ Wallingford, Pa.: Pendle Hill Publications, 1984.

- Peter Bien, Kazantzakis. Politics of the Spirit, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1989.

- Darren J. N. Middleton and Peter Bien, ed., God's struggler. Religion in the Writings of Nikos Kazantzakis, Macon, Ga.: Mercer University Press, 1996

- Darren J. N. Middleton, Novel Theology: Nikos Kazantzakis' Encounter with Whiteheadian Process Theism, Macon, Ga.: Mercer University Press, 2000.

- Darren J. N. Middleton, Scandalizing Jesus?: Kazantzakis' 'Last Temptation of Christ' Fifty Years On, New York: Continuum, 2005.

- Darren J. N. Middleton, Broken Hallelujah: Nikos Kazantzakis and Christian Theology, Lanham, Md.: Rowman and Littlefield, 2006.

- Helen Kazantzakis, Nikos Kazantzakis. A biography based on his letters, translated by Amy Mims, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1968; Bruno Cassirer, Oxford, 1968; Berkeley: Creative Arts Book Co. for Donald S. Ellis, 1983.

- John (Giannes) Anapliotes, The real Zorbas and Nikos Kazantzakis, translated by Lewis A. Richards, Amsterdam: Hakkert, 1978.

- James F. Lea, Kazantzakis: The Politics of Salvation, foreword by Helen Kazantzakis, The University of Alabama Press, 1979.

- Kimon Friar, The spiritual odyssey of Nikos Kazantzakis. A talk, edited and with an introduction by Theofanis G. Stavrou, St. Paul, Minn.: North Central Pub. Co., 1979.

- Morton P. Levitt, The Cretan Glance, The World and Art of Nikos Kazantzakis, Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press, 1980.

- Daniel A. Dombrowski, Kazantzakis and God, Albany: State University of New York Press, 1997.

- Colin Wilson and Howard F. Dossor, Nikos Kazantzakis, Nottingham: Paupers, 1999.

- Dossor, Howard F The Existential Theology of Nikos Kazantzakis Wallingford Pa (Pendle Hill Pamphlets No 359), 2002

- Lewis Owen, Creative Destruction: Nikos Kazantzakis and the Literature of Responsibility, Macon, Ga.: Mercer University Press, 2003.

- Ioannis G. Zaglaris, "Nikos Kazantzakis and thought leadership", 2013.

- Ioannis G. Zaglaris, "Nikos Kazantzakis - end of time due to copyright", GISAP: Educational Sciences, 4, pp. 53-54, 2014

- Ioannis G. Zaglaris, "Challenge in Writing", 2015

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nikos Kazantzakis. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to Nikos Kazantzakis. |

- The Nikos Kazantzakis Museum, Crete

- The Nikos Kazantzakis Pages at the Historical Museum of Crete

- Iran to pay homage to Greek author Kazantzakis – Tehran Times, 10 April 2008

- Society of Nikos Kazantzakis friends (in Greek)

- Kazantzakis museum

- Nikos Kazantzakis Quotes

- Nikos Kazantzakis at Library of Congress Authorities, with 128 catalogue records

- Nikos Kazantzakis

- 1883 births

- 1957 deaths

- 20th-century Greek philosophers

- 20th-century Greek poets

- 20th-century Greek novelists

- People from Ottoman Crete

- Greeks of the Ottoman Empire

- Greek nationalists

- 20th-century Greek dramatists and playwrights

- Greek agnostics

- Writers from Heraklion

- Cretan novelists

- Greek journalists

- 20th-century travel writers

- Greek travel writers

- Greek speculative fiction writers

- National and Kapodistrian University of Athens alumni

- Greek male poets

- Greek male novelists

- Greek socialists

- Male dramatists and playwrights

- Criticism of Eastern Orthodox Church

- Translators of Dante Alighieri

- Translators of Homer

- Translators of Friedrich Nietzsche

- Epic poets

- 20th-century journalists