Tara (Buddhism)

| Tārā | |

|---|---|

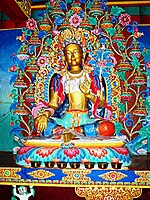

Tara image from Bihar, 10th century India | |

| Sanskrit | तारा Tārā |

| Chinese | (Traditional) 多羅菩薩 (Simplified) 多罗菩萨 (Pinyin: Duōluó Púsà) 度母 (Pinyin: Dùmǔ) |

| Japanese | (romaji: Tara Bosatsu) |

| Korean | 다라보살 (RR: Dara Bosal) |

| Mongolian | Ногоон дарь эх |

| Thai | พระนางตารา |

| Tibetan | རྗེ་བརྩུན་སྒྲོལ་མ།། |

| Vietnamese | Đa La Bồ Tát Độ Mẫu |

| Information | |

| Venerated by | Mahāyāna, Vajrayāna |

| Part of a series on |

| Tibetan Buddhism |

|---|

|

Tara (Sanskrit: तारा, tārā; Tib. སྒྲོལ་མ, Dölma), Ārya Tārā, or Shayama Tara, also known as Jetsun Dölma (Tibetan language: rje btsun sgrol ma) is an important figure in Buddhism, especially revered in Tibetan Buddhism. She appears as a female bodhisattva in Mahayana Buddhism, and as a female Buddha in Vajrayana Buddhism. She is known as the "mother of liberation", and represents the virtues of success in work and achievements. She is known as Tara Bosatsu (多羅菩薩) in Japan, and as Duōluó Púsà (多羅菩薩) in Chinese Buddhism.[1]

Tārā is a meditation deity revered by practitioners of the Tibetan branch of Vajrayana Buddhism to develop certain inner qualities and to understand outer, inner and secret teachings such as karuṇā (compassion), mettā (loving-kindness), and shunyata (emptiness). Tārā may more properly be understood as different aspects of the same quality, as bodhisattvas are often considered personifications of Buddhist methods.

There is also recognition in some schools of Buddhism of twenty-one Tārās. A practice text entitled Praises to the Twenty-One Taras, is the most important text on Tara in Tibetan Buddhism. Another key text is the Tantra Which is the Source for All the Functions of Tara, Mother of All the Tathagatas.[2]

The main Tārā mantra is the same for Buddhists and Hindus alike: oṃ tāre tuttāre ture svāhā. It is pronounced by Tibetans and Buddhists who follow the Tibetan traditions as oṃ tāre tu tāre ture soha. The literal translation would be “Oṃ O Tārā, I pray O Tārā, O Swift One, So Be It!”

Emergence of Tārā as a Buddhist deity[edit]

Within Tibetan Buddhism Tārā is regarded as a bodhisattva of compassion and action. She is the female aspect of Avalokiteśvara and in some origin stories she comes from his tears:

"Then at last Avalokiteshvara arrived at the summit of Marpori, the 'Red Hill', in Lhasa. Gazing out, he perceived that the lake on Otang, the 'Plain of Milk', resembled the Hell of Ceaseless Torment. Myriad beings were undergoing the agonies of boiling, burning, hunger, thirst, yet they never perished, sending forth hideous cries of anguish all the while. When Avalokiteshvara saw this, tears sprang to his eyes. A teardrop from his right eye fell to the plain and became the reverend Bhrikuti, who declared: "Child of your lineage! As you are striving for the sake of sentient beings in the Land of Snows, intercede in their suffering, and I shall be your companion in this endeavour!" Bhrikuti was then reabsorbed into Avalokiteshvara's right eye, and was reborn in a later life as the Nepalese princess Tritsun. A teardrop from his left eye fell upon the plain and became the reverend Tara. She also declared, "Child of your lineage! As you are striving for the sake of sentient beings in the Land of Snows, intercede in their suffering, and I shall be your companion in this endeavor!" Tārā was then reabsorbed into Avalokiteshvara's left eye."

Tārā manifests in many different forms. In Tibet, these forms included Green Tārā's manifestation as the Nepalese Princess (Bhrikuti),[3] and White Tārā's manifestation as the Chinese princess Kongjo (Princess Wencheng).[4]

Tārā is also known as a saviouress, as a heavenly deity who hears the cries of beings experiencing misery in saṃsāra.

Whether the Tārā figure originated as a Buddhist or Hindu goddess is unclear and remains a source of inquiry among scholars. Mallar Ghosh believes her to have originated as a form of the goddess Durga in the Hindu Puranas.[5] Today, she is worshiped both in Buddhism and in Shaktism (Hinduism) as one of the ten Mahavidyas. It may be true that goddesses entered Buddhism from Shaktism (i.e. the worship of local or folk goddesses prior to the more institutionalized Hinduism which had developed by the early medieval period (i.e. Middle kingdoms of India). According to Beyer, it would seem that the feminine principle makes its first appearance in Buddhism as the goddess who personified prajnaparamita.[6]

Tārā came to be seen as an expression of the compassion of perfected wisdom only later, with her earliest textual reference being the Mañjuśrī-mūla-kalpa (c. 5th–8th centuries CE).[7] The earliest, solidly identifiable image of Tārā is most likely that which is still found today at cave 6 within the rock-cut Buddhist monastic complex of the Ellora Caves in Maharashtra (c. 7th century CE), with her worship being well established by the onset of the Pala Empire in Eastern India (8th century CE).[8]

Tārā became a very popular Vajrayana deity with the rise of Tantra in 8th-century Pala and, with the movement of Indian Buddhism into Tibet through Padmasambhava, the worship and practices of Tārā became incorporated into Tibetan Buddhism as well.[6][9] She eventually came to be considered the "Mother of all Buddhas," which usually refers to the enlightened wisdom of the Buddhas, while simultaneously echoing the ancient concept of the Mother Goddess in India.

Independent of whether she is classified as a deity, a Buddha, or a bodhisattva, Tārā remains very popular in Tibet (and Tibetan communities in exile in Northern India), Mongolia, Nepal, Bhutan, Sikkim and is worshiped in a majority of Buddhist communities throughout the world (see also Guanyin, the female aspect of Avalokitesvara in Chinese Buddhism).

Today, Green Tara and White Tara are probably the most popular representations of Tara. Green Tara (Khadiravani) is usually associated with protection from fear and the following eight obscurations: lions (= pride), wild elephants (= delusion/ignorance), fires (= hatred and anger), snakes (= jealousy), bandits and thieves (= wrong views, including fanatical views), bondage (= avarice and miserliness), floods (= desire and attachment), and evil spirits and demons (= deluded doubts). As one of the three deities of long life, White Tara (Saraswati) is associated with longevity. White Tara counteracts illness and thereby helps to bring about a long life. She embodies the motivation that is compassion and is said to be as white and radiant as the moon.

Origin as a Buddhist bodhisattva[edit]

Tārā has many stories told which explain her origin as a bodhisattva.

In this tale there is a young princess who lives in a different world system, millions of years in the past. Her name is Jnanachanrda or Yeshe Dawa, which means "Moon of Primordial Awareness". For quite a number of aeons she makes offerings to the Buddha of that world system, whose name was Tonyo Drupa. She receives special instruction from him concerning bodhicitta - the infinitely compassionate mental state of a bodhisattva. After doing this, some monks approach her and suggest that because of her level of attainment she should next pray to be reborn as a male to progress further. At this point she lets the monks know in no uncertain terms that it is only "weak minded worldlings" who see gender as a barrier to attaining enlightenment. She sadly notes there have been few who wish to work for the welfare of sentient beings in a female form, though. Therefore, she resolves to always be reborn as a female bodhisattva, until samsara is no more.[11] She then stays in a palace in a state of meditation for some ten million years, and the power of this practice releases tens of millions of beings from suffering. As a result of this, Tonyo Drupa tells her she will henceforth manifest supreme bodhi as the Goddess Tārā in many world systems to come.

With this story in mind, it is interesting to juxtapose this with a quotation from the 14th Dalai Lama about Tārā, spoken at a conference on Compassionate Action in Newport Beach, CA in 1989:

Tārā, then, embodies certain ideals which make her attractive to women practitioners, and her emergence as a Bodhisattva can be seen as a part of Mahayana Buddhism's reaching out to women, and becoming more inclusive even in 6th-century CE India.

Symbols and associations[edit]

Tārā's name literally means "star" or "planet", and therefore she is associated with navigation and travel both literally and metaphorically as spiritual crossing to the 'other side' of the ocean of existence (enlightenment).[12] Hence she is known literally as "she who saves" in Tibetan.[13] In the 108 Names of the Holy Tara, Tara is 'Leader of the caravans ..... who showeth the way to those who have lost it' and she is named as Dhruva, the Sanskrit name for the North Star.[13]

According to Miranda Shaw, "Motherhood is central to the conception of Tara".[14] Her titles include "loving mother", "supreme mother", "mother of the world", "universal mother" and "mother of all Buddhas".[15]

She is most often shown with the blue lotus or night lotus (utpala), which releases its fragrance with the appearance of the moon and therefore Tārā is also associated with the moon and night.[16][13]

Tārā is also a forest goddess, particularly in her form as Khadiravani, "dweller in the Khadira forest" and is generally associated with plant life, flowers, acacia (khadira) trees and the wind. Because of her association with nature and plants, Tārā is also known as a healing goddess (especially as White Tārā) and as a goddess of nurturing quality and fertility.[17] Her pure land in Mount Potala is described as "Covered with manifold trees and creepers, resounding with the sound of many birds, And with murmur of waterfalls, thronged with wild beasts of many kinds; Many species of flowers grow everywhere."[18] Her association with the wind element (vaayu) also means that she is swift in responding to calls for any aid.

Tārā as a saviouress[edit]

Tārā also embodies many of the qualities of feminine principle. She is known as the Mother of Mercy and Compassion. She is the source, the female aspect of the universe, which gives birth to warmth, compassion and relief from bad karma as experienced by ordinary beings in cyclic existence. She engenders, nourishes, smiles at the vitality of creation, and has sympathy for all beings as a mother does for her children. As Green Tārā she offers succor and protection from all the unfortunate circumstances one can encounter within the samsaric world. As White Tārā she expresses maternal compassion and offers healing to beings who are hurt or wounded, either mentally or psychically. As Red Tārā she teaches discriminating awareness about created phenomena, and how to turn raw desire into compassion and love. As Blue Tārā (Ekajati) she becomes a protector in the Nyingma lineage, who expresses a ferocious, wrathful, female energy whose invocation destroys all Dharmic obstacles that engender good luck and swift spiritual awakening.[6]

Within Tibetan Buddhism, she has 21 major forms in all, each tied to a certain color and energy. And each offers some feminine attribute, of ultimate benefit to the spiritual aspirant who asks for her assistance.

Another quality of feminine principle which she shares with the dakinis is playfulness. As John Blofeld expands upon in Bodhisattva of Compassion,[19] Tārā is frequently depicted as a young sixteen-year-old girlish woman. She often manifests in the lives of dharma practitioners when they take themselves, or the spiritual path too seriously. There are Tibetan tales in which she laughs at self-righteousness, or plays pranks on those who lack reverence for the feminine. In Magic Dance: The Display of the Self-Nature of the Five Wisdom Dakinis,[20] Thinley Norbu explores this as "Playmind". Applied to Tārā one could say that her playful mind can relieve ordinary minds which become rigidly serious or tightly gripped by dualistic distinctions. She takes delight in an open mind and a receptive heart then. For in this openness and receptivity her blessings can naturally unfold and her energies can quicken the aspirants spiritual development.

These qualities of feminine principle then, found an expression in Indian Mahayana Buddhism and the emerging Vajrayana of Tibet, as the many forms of Tārā, as dakinis, as Prajnaparamita, and as many other local and specialized feminine divinities. As the worship of Tārā developed, various prayers, chants and mantras became associated with her. These came out of a felt devotional need, and from her inspiration causing spiritual masters to compose and set down sadhanas, or tantric meditation practices. Two ways of approach to her began to emerge. In one common folk and lay practitioners would simply directly appeal to her to ease some of the travails of worldly life. In the second, she became a Tantric deity whose practice would be used by monks or tantric yogis in order to develop her qualities in themselves, ultimately leading through her to the source of her qualities, which are Enlightenment, Enlightened Compassion, and Enlightened Mind.

Tārā as a Tantric deity[edit]

Tārā as a focus for tantric deity yoga can be traced back to the time period of Padmasambhava. There is a Red Tārā practice which was given by Padmasambhava to Yeshe Tsogyal. He asked that she hide it as a treasure. It was not until the 20th century, that a great Nyingma lama, Apong Terton rediscovered it. It is said that this lama was reborn as Sakya Trizin, present head of the Sakyapa sect. A monk who had known Apong Terton succeeded in retransmitting it to Sakya Trizin, and the same monk also gave it to Chagdud Tulku Rinpoche, who released it to his western students.

Martin Willson in In Praise of Tārā traces many different lineages of Tārā Tantras, that is Tārā scriptures used as Tantric sadhanas.[21] For example, a Tārā sadhana was revealed to Tilopa (988–1069 CE), the human father of the Karma Kagyu. Atisa, the great translator and founder of the Kadampa school of Tibetan Buddhism, was a devotee of Tārā. He composed a praise to her, and three Tārā Sadhanas. Martin Willson's work also contains charts which show origins of her tantras in various lineages, but suffice to say that Tārā as a tantric practice quickly spread from around the 7th century CE onwards, and remains an important part of Vajrayana Buddhism to this day.

The practices themselves usually present Tārā as a tutelary deity (thug dam, yidam) which the practitioners sees as being a latent aspect of one's mind, or a manifestation in a visible form of a quality stemming from Buddha Jnana. As John Blofeld puts it in The Tantric Mysticism of Tibet:

Forms[edit]

There are many forms of Tārā, including various popular lists of 21 different emanations of Tārā. Green Tārā, (śyāmatārā) associated with peacefulness and enlightened activity is the most depicted and the central aspect of Tārā from which others such as the 21 Tārās emanate. In her Green form, she is often also known as Khadiravaṇi-Tārā (Tārā of the acacia forest), who appeared to Nagarjuna in the Khadiravani forest of South India and protects from the eight great fears. She is often accompanied by her two attendants Mārīcī and Ekajaṭā. Dharmachari Purna writes on the various forms of Tara:

According to Sarvajnamitra she has a “universal form” (visva-rupa), that encompasses all living beings and deities, and which changes with the needs of each being.[23]

Other forms of Tārā include:

- White Tārā, (Sitatārā) with two arms seated on a white lotus and with eyes on her hand and feet, as well as a third eye on her forehead (thus she is also known as "Seven eyed"). She is known for compassion, long life, healing and serenity.[24] Also known as The Wish-fulfilling Wheel, or Cintachakra.

- Pravīratārā, "Tārā Swift and Heroic", a Red colored form with eight arms holding bell and vajra, bow and arrow, wheel, conch, sword and noose.

- Kurukullā (Rikchema) of red color and fierce aspect associated with magnetizing all good things

- Black Tārā (Ugra Tārā), associated with power

- Various forms of Yellow or Golden colored Tārās, sometimes associated with wealth and prosperity including "Yellow Cintamani Tārā" (“Wish-Granting Gem Tara”) holding a wish granting jewel, eight armed "Vajra Tārā" and golden "Rajasri Tārā" holding a blue lotus.[25]

- Blue Tārā (Ekajati), wrathful with many heads and arms, associated with transmutation of anger

- Cintāmaṇi Tārā, a form of Tārā widely practiced at the level of Highest Yoga Tantra in the Gelug School of Tibetan Buddhism, portrayed as green and often conflated with Green Tārā

- Sarasvati (Yangchenma), known for the arts, knowledge and wisdom

- Bhṛkuṭītārā (Tronyer Chendze), "Tārā with a Frown", known for protection from spirits

- Uṣṇīṣavijaya Tārā, White Tārā named "Victorious Uṣṇīṣa" with three faces and twelve arms, associated with long life

- Golden Prasanna Tārā - wrathful form, with a necklace of bloody heads and sixteen arms holding an array of weapons and Tantric attributes.

- Yeshe Tsogyal ("Wisdom Lake Queen"), the consort of Padmasambhava who brought Buddhism to Tibet, was known as an emanation of Tārā

- Rigjay Lhamo, “Goddess Who Brings Forth Awareness,” seated in royal posture surrounded by rainbow light.

- Sitatapatra Tārā, protector against supernatural danger

Tārā's iconography such as the lotus also shows resemblance with the Hindu goddess Lakshmi, and at least one Tibetan liturgy evokes Lakshmi as Tārā.[26] According to Miranda Shaw, there is a later trend of Tārā theology that began to see all other female divinities as aspects of Tārā or at least associated with her. Apart from her many emanations named Tārā of varying colors, other Mahayana female divinities that became part of Tara's theology include Janguli, Parnasabari, Cunda, Kurukulla, Mahamayuri, Usnisavijaya, and Marici. Based on this principle of Tārā as the central female divinity, Dakinis were also seen as emanations of her.[27]

Sadhanas of Tārā[edit]

Sadhanas in which Tārā is the yidam (meditational deity) can be extensive or quite brief. Most all of them include some introductory praises or homages to invoke her presence and prayers of taking refuge. Then her mantra is recited, followed by a visualization of her, perhaps more mantra, then the visualization is dissolved, followed by a dedication of the merit from doing the practice. Additionally there may be extra prayers of aspirations, and a long life prayer for the Lama who originated the practice. Many of the Tārā sadhanas are seen as beginning practices within the world of Vajrayana Buddhism, however what is taking place during the visualization of the deity actually invokes some of the most sublime teachings of all Buddhism. Two examples are Zabtik Drolchok[28] and Chime Pakme Nyingtik.[29]

In this case during the creation phase of Tārā as a yidam, she is seen as having as much reality as any other phenomena apprehended through the mind. By reciting her mantra and visualizing her form in front, or on the head of the adept, one is opening to her energies of compassion and wisdom. After a period of time the practitioner shares in some of these qualities, becomes imbued with her being and all it represents. At the same time all of this is seen as coming out of Emptiness and having a translucent quality like a rainbow. Then many times there is a visualization of oneself as Tārā. One simultaneously becomes inseparable from all her good qualities while at the same time realizing the emptiness of the visualization of oneself as the yidam and also the emptiness of one's ordinary self.

This occurs in the completion stage of the practice. One dissolves the created deity form and at the same time also realizes how much of what we call the "self" is a creation of the mind, and has no long term substantial inherent existence. This part of the practice then is preparing the practitioner to be able to confront the dissolution of one's self at death and ultimately be able to approach through various stages of meditation upon emptiness, the realization of Ultimate Truth as a vast display of Emptiness and Luminosity. At the same time the recitation of the mantra has been invoking Tārā's energy through its Sanskrit seed syllables and this purifies and activates certain psychic centers of the body (chakras). This also untangles knots of psychic energy which have hindered the practitioner from developing a Vajra body, which is necessary to be able to progress to more advanced practices and deeper stages of realization.

Therefore, even in a simple Tārā sadhana a plethora of outer, inner, and secret events is taking place and there are now many works such as Deity Yoga, compiled by the present Dalai Lama,[30] which explores all the ramifications of working with a yidam in Tantric practices.

The end results of doing such Tārā practices are many. For one thing it reduces the forces of delusion in the forms of negative karma, sickness, afflictions of kleshas, and other obstacles and obscurations.

The mantra helps generate Bodhicitta within the heart of the practitioner and purifies the psychic channels (nadis) within the body allowing a more natural expression of generosity and compassion to flow from the heart center. Through experiencing Tārā's perfected form one acknowledges one's own perfected form, that is one's intrinsic Buddha nature, which is usually covered over by obscurations and clinging to dualistic phenomena as being inherently real and permanent.

The practice then weans one away from a coarse understanding of Reality, allowing one to get in touch with inner qualities similar to those of a bodhisattva, and prepares one's inner self to embrace finer spiritual energies, which can lead to more subtle and profound realizations of the Emptiness of phenomena and self.

As Chagdud Tulku Rinpoche, in his Introduction to the Red Tārā Sadhana,[31] notes of his lineage: "Tārā is the flawless expression of the inseparability of emptiness, awareness and compassion. Just as you use a mirror to see your face, Tārā meditation is a means of seeing the true face of your mind, devoid of any trace of delusion".

There are several preparations to be done before practising the Sadhana. To perform a correct execution the practitioner must be prepared and take on the proper disposition. The preparations may be grouped as "internal" and "external". Both are necessary to achieve the required concentration.

[edit]

Terma teachings are "hidden teachings" said to have been left by Padmasambhava (8th century) and others for the benefit of future generations. Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo discovered Phagme Nyingthig (Tib. spelling: 'chi med 'phags ma'i snying thig, Innermost Essence teachings of the Immortal Bodhisattva [Arya Tārā]).[33]

Earlier in the 19th century, according to a biography,[34] Nyala Pema Dündul received a Hidden Treasure, Tārā Teaching and Nyingthig (Tib. nying thig) from his uncle Kunsang Dudjom (Tib. kun bzang bdud 'joms). It is not clear from the source whether the terma teaching and the nyingthig teachings refer to the same text or two different texts.

See also[edit]

- Nairatmya

- Praises to the Twenty-One Taras

- Golden Tara, Mahayana Buddhist deity's statue discovered in Philippines

- Tara (Devi)

References[edit]

- ^ Buddhist Deities: Bodhisattvas of Compassion

- ^ Beyer, Stephan; The Cult of Tara Magic and Ritual, page 13.

- ^ ((Min Bahadur Shakya |title=The Life and Contribution of the Nepalese Princess Bhrikuti Devi to Tibetan History |year=2009 |publisher=Pilgrims Publishing))

- ^ Sakyapa Sonam Gyaltsen (1996). The Clear Mirror: A Traditional Account of Tibet's Golden Age. Snow Lion Publications. pp. 64–65. ISBN 1-55939-048-4.

- ^ Mallar Ghosh (1980). Development of Buddhist Iconography in Eastern India. Munshiram Manoharlal. p. 17. ISBN 81-215-0208-X.

- ^ a b c Stephen Beyer (1978). The Cult of Tārā: Magic and Ritual in Tibet (Hermeneutics: Studies in the History of Religions). University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03635-2.

- ^ Martin Willson (1992). In Praise of Tārā: Songs to the Saviouress. Wisdom Publications. p. 40. ISBN 0-86171-109-2.

- ^ Mallar Ghosh (1980). Development of Buddhist Iconography in Eastern India. Munshiram Manoharlal. p. 6. ISBN 81-215-0208-X.

- ^ Khenchen Palden Sharab; Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal (2007). Tara's Enlightened Activity: Commentary on the Praises to the Twenty-one Taras. Snow Lion Publications. p. 13. ISBN 1-55939-287-8.

- ^ "The Buddhist Goddess Tara". The Walters Art Museum.

- ^ Arni, Samhita (2017-03-09). "Gender doesn't come in the way of Nirvana". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2019-12-14.

- ^ Shaw, Miranda; Buddhist goddesses of India, page 310

- ^ a b c d Purna, Dharmachari; Tara: Her Origins and Development, http://www.westernbuddhistreview.com/vol2/tara_origins_a_development.html

- ^ Shaw, Miranda; Buddhist goddesses of India, page 316

- ^ Shaw, Miranda; Buddhist goddesses of India, page 316-317

- ^ Beer, Robert; The Handbook of Tibetan Buddhist Symbols, page 170

- ^ Shaw, Miranda; Buddhist goddesses of India, page 324

- ^ Edward Conze, Buddhist Texts Through the Ages, p.196.

- ^ John Blofeld (2009). Bodhisattva of Compassion: The Mystical Tradition of Kuan Yin. Shambhala Publications. ISBN 1-59030-735-6.

- ^ Thinley Norbu (1999). Magic Dance: The Display of the Self-Nature of the Five Wisdom Dakinis. Shambhala Publications. ISBN 0-87773-885-8.

- ^ Martin Willson (1992). In Praise of Tārā: Songs to the Saviouress. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-109-2.

- ^ John Blofeld (1992). The Tantric Mysticism of Tibet: A Practical Guide to the Theory, Purpose, and Techniques of Tantric Meditation. Penguin. p. 176. ISBN 0-14-019336-7.

- ^ Shaw, Miranda; Buddhist Goddesses of India, page 337

- ^ Shaw, Miranda; Buddhist Goddesses of India, page 333

- ^ Shaw, Miranda; Buddhist Goddesses of India, page 339

- ^ Shaw, Miranda; Buddhist goddesses of India, page 332

- ^ Shaw, Miranda; Buddhist goddesses of India, page 341

- ^ http://www.rigpawiki.org/index.php?title=Zabtik_Drolchok

- ^ http://www.rigpawiki.org/index.php?title=Chim%C3%A9_Phakm%C3%A9_Nyingtik

- ^ Dalai Lama (1987). Deity Yoga: In Action and Performance Tantra. Snow Lion Publications. ISBN 0-937938-50-5.

- ^ Chagdud Tulku Rinpoche (1998). Red Tara Commentary: Instructions for the Concise Practice Known as Red Tara—An Open Door to Bliss. Padma Publishing. ISBN 1-881847-04-7.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-09-05. Retrieved 2012-05-26.

- ^ Tulku Thondup (1999). Masters of Meditation and Miracles: Lives of the Great Buddhist Masters of India and Tibet. Shambhala Publications. p. 218. ISBN 1-57062-509-3.

- ^ Biography of Pema Dudul