Culture of Russia

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

(Redirected from Russian culture)

Saint Basil's Cathedral on Red Square in Moscow

"Scarlet Sails" celebration in Saint Petersburg (Watch on YouTube)

The culture of the Russians, along with the cultures of many other minority ethnic groups in the country—has a long tradition of achievement in many fields,[1] especially when it comes to literature,[2] folk dancing,[3] philosophy, classical music,[4][5] traditional folk-music, ballet,[6] architecture, painting, cinema,[7] animation and politics. In all these areas Russia has had a considerable influence on global culture. Russia also has a rich material culture and a tradition in science and technology.

Contents

1Language and literature

1.1Folklore

1.2Literature

1.3Philosophy

1.4Humour

2Visual arts

2.1Architecture

2.2Handicraft

2.3Icon painting

2.4Lubok

2.5Classical painting

2.6Realist painting

2.7Russian avant-garde

2.8Soviet art

3Performance arts

3.1Russian folk music

3.2Russian folk dance

3.3Classical music

3.4Ballet

3.5Opera

3.6Modern music

3.7Cinema

3.8Animation

4Science and technology

4.1Radio and TV

4.2Internet

4.3Science and innovation

4.4Space exploration

5Lifestyle

5.1Ethnic dress of Russian people

5.2Cuisine

5.3Traditions

5.4Holidays

5.5Religion

5.6Cossack culture in Russia

5.7Russian forest culture

5.8More elements of Russian society and culture

6Sports

6.1Basketball

6.2Ice hockey

6.3Bandy

6.4Football

6.5Martial arts

7National symbols

7.1State symbols

7.2Unofficial symbols

8Tourism

8.1Cultural tourism

8.2Resorts and nature tourism

9See also

10References

11External links

Language and literature[edit source]

Main article: Russian language

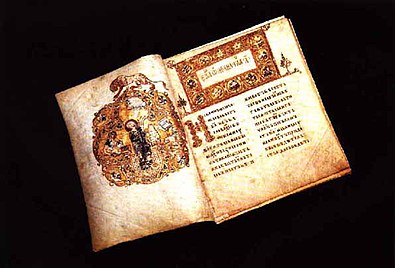

The Ostromir Gospels, the second oldest East Slavic book known; 1056 AD; Russian National Library (Saint Petersburg)

Page of a Russian illuminated manuscript; 1485–1490

Russia's 160 ethnic groups speak some 100 languages.[1] According to the 2002 census, 142.6 million people speak Russian, followed by Tatar with 5.3 million and Ukrainian with 1.8 million speakers.[8] Russian is the only official state language, but the Constitution gives the individual republics the right to make their native language co-official next to Russian.[9] Despite its wide dispersal, the Russian language is homogeneous throughout Russia. Russian is the most geographically widespread language of Eurasia and the most widely spoken Slavic language.[10] Russian belongs to the Indo-European language family and is one of the living members of the East Slavic languages; the others being Belarusian and Ukrainian (and possibly Rusyn). Written examples of Old East Slavic (Old Russian) are attested from the 10th century onwards.[11]

Over a quarter of the world's scientific literature is published in Russian. Russian is also applied as a means of coding and storage of universal knowledge—60–70% of all world information is published in the English and Russian languages.[12] The language is one of the six official languages of the United Nations.

Folklore[edit source]

Main articles: Slavic mythology and Russian folklore

New Russian folklore takes its roots in the pagan beliefs of ancient Slavs, which is nowadays still represented in the Russian folklore. Epic Russian bylinas are also an important part of Slavic mythology. The oldest bylinas of Kievan cycle were actually recorded mostly in the Russian North, especially in Karelia, where most of the Finnish national epic Kalevala was recorded as well.

Buyan by Ivan Bilibin

Many Russian fairy tales and bylinas were adapted for Russian animations, or for feature movies by famous directors like Aleksandr Ptushko (Ilya Muromets, Sadko) and Aleksandr Rou (Morozko, Vasilisa the Beautiful). Some Russian poets, including Pyotr Yershov and Leonid Filatov, created a number of well-known poetical interpretations of classical Russian fairy tales, and in some cases, like that of Alexander Pushkin, also created fully original fairy tale poems that became very popular.

Folklorists today consider the 1920s the Soviet Union's golden age of folklore. The struggling new government, which had to focus its efforts on establishing a new administrative system and building up the nation's backwards economy, could not be bothered with attempting to control literature, so studies of folklore thrived. There were two primary trends of folklore study during the decade: the formalist and Finnish schools. Formalism focused on the artistic form of ancient byliny and faerie tales, specifically their use of distinctive structures and poetic devices.[13] The Finnish school was concerned with connections amongst related legends of various Eastern European regions. Finnish scholars collected comparable tales from multiple locales and analyzed their similarities and differences, hoping to trace these epic stories' migration paths.[14]

Emblem of the Ministry of Culture of Russia. The image of the crowned double eagle and the central crown which is connected with the other two crowns is often used as a pictorial example of Russia's cultural nature. One crowned head looks to Europe and reflects the Western European element in Russian culture, the other looks to Asia and symbolizes the Asian Oriental element in Russia. Both are connected to a big third crown. Russian culture is connected with European and Asian cultures and was influenced by both.[15]

Once Joseph Stalin came to power and put his first five-year plan into motion in 1928, the Soviet government began to criticize and censor folklore studies. Stalin and the Soviet regime repressed folklore, believing that it supported the old tsarist system and a capitalist economy. They saw it as a reminder of the backward Russian society that the Bolsheviks were working to surpass.[16] To keep folklore studies in check and prevent "inappropriate" ideas from spreading amongst the masses, the government created the RAPP – the Russian Association of Proletarian Writers. The RAPP specifically focused on censoring fairy tales and children's literature, believing that fantasies and "bourgeois nonsense" harmed the development of upstanding Soviet citizens. Fairy tales were removed from bookshelves and children were encouraged to read books focusing on nature and science.[17] RAPP eventually increased its levels of censorship and became the Union of Soviet Writers in 1932.

Bogatyrs by Viktor Vasnetsov. The three heroes of Russian mythology: (l-r) Dobrynya Nikitich, Ilya Muromets and Alyosha Popovich

In order to continue researching and analyzing folklore, intellectuals needed to justify its worth to the Communist regime. Otherwise, collections of folklore, along with all other literature deemed useless for the purposes of Stalin's Five Year Plan, would be an unacceptable realm of study. In 1934, Maksim Gorky gave a speech to the Union of Soviet Writers arguing that folklore could, in fact, be consciously used to promote Communist values. Apart from expounding on the artistic value of folklore, he stressed that traditional legends and fairy tales showed ideal, community-oriented characters, which exemplified the model Soviet citizen.[18] Folklore, with many of its conflicts based on the struggles of a labor-oriented lifestyle, was relevant to Communism as it could not have existed without the direct contribution of the working classes.[19] Also, Gorky explained that folklore characters expressed high levels of optimism, and therefore could encourage readers to maintain a positive mindset, especially as their lives changed with the further development of Communism.[14]

Yuri Sokolov, the head of the folklore section of the Union of Soviet Writers also promoted the study of folklore by arguing that folklore had originally been the oral tradition of the working people, and consequently could be used to motivate and inspire collective projects amongst the present-day proletariat.[20] Characters throughout traditional Russian folktales often found themselves on a journey of self-discovery, a process that led them to value themselves not as individuals, but rather as a necessary part of a common whole. The attitudes of such legendary characters paralleled the mindset that the Soviet government wished to instill in its citizens.[21] He also pointed out the existence of many tales that showed members of the working class outsmarting their cruel masters, again working to prove folklore's value to Soviet ideology and the nation's society at large.[22] Convinced by Gorky and Sokolov's arguments, the Soviet government and the Union of Soviet Writers began collecting and evaluating folklore from across the country. The Union handpicked and recorded particular stories that, in their eyes, sufficiently promoted the collectivist spirit and showed the Soviet regime's benefits and progress. It then proceeded to redistribute copies of approved stories throughout the population. Meanwhile, local folklore centers arose in all major cities.[23] Responsible for advocating a sense of Soviet nationalism, these organizations ensured that the media published appropriate versions of Russian folktales in a systematic fashion.[14]

Sadko in the Underwater Tsardom by Ilya Repin

Apart from circulating government-approved fairy tales and byliny that already existed, during Stalin's rule authors parroting appropriate Soviet ideologies wrote Communist folktales and introduced them to the population. These contemporary folktales combined the structures and motifs of the old byliny with contemporary life in the Soviet Union. Called noviny, these new tales were considered the renaissance of the Russian epic.[24] Folklorists were called upon to teach modern folksingers the conventional style and structure of the traditional byliny. They also explained to the performers the appropriate types of Communist ideology that should be represented in the new stories and songs[25] As the performers of the day were often poorly educated, they needed to obtain a thorough understanding of Marxist ideology before they could be expected to impart folktales to the public in a manner that suited the Soviet government. Besides undergoing extensive education, many folk performers traveled throughout the nation in order to gain insight into the lives of the working class, and thus communicate their stories more effectively.[26] Due to their crucial role in spreading Communist ideals throughout the Soviet Union, eventually some of these performers became highly valued members of Soviet society. A number of them, despite their illiteracy, were even elected as members of the Union of Soviet Writers.[27]

These new Soviet fairy tales and folk songs primarily focused on the contrasts between a miserable life in old tsarist Russia and an improved one under Stalin's leadership.[28] Their characters represented identities for which Soviet citizens should strive, exemplifying the traits of the "New Soviet Man".[29] The heroes of Soviet tales were meant to portray a transformed and improved version of the average citizen, giving the reader a clear goal for an ideal community-oriented self that the future he or she was meant to become. These new folktales replaced magic with technology, and supernatural forces with Stalin.[30] Instead of receiving essential advice from a mythical being, the protagonist would be given advice from omniscient Stalin. If the character followed Stalin's divine advice, he could be assured success in all his endeavors and a complete transformation into the "New Soviet Man".[31] The villains of these contemporary fairy tales were the Whites and their leader Idolisce, "the most monstrous idol", who was the equivalent of the tsar. Descriptions of the Whites in noviny mirrored those of the Tartars in byliny.[32] In these new stories, the Whites were incompetent, stagnant capitalists, while the Soviet citizens became invincible heroes.[33]

Once Stalin died in March 1953, folklorists of the period quickly abandoned the new folktales. Written by individual authors and performers, noviny did not come from the oral traditions of the working class. Consequently, today they are considered pseudo-folklore, rather than genuine Soviet (or Russian) folklore.[34] Without any true connection to the masses, there was no reason noviny should be considered anything other than contemporary literature. Specialists decided that attempts to represent contemporary life through the structure and artistry of the ancient epics could not be considered genuine folklore.[35] Stalin's name has been omitted from the few surviving pseudo-folktales of the period.[34] Instead of considering folklore under Stalin a renaissance of the traditional Russian epic, today it is generally regarded as a period of restraint and falsehood.

Literature[edit source]

Main articles: Russian literature, List of Russian-language poets, and List of Russian-language writers

Russian literature is considered to be among the most influential and developed in the world, with some of the most famous literary works belonging to it.[2] Russia's literary history dates back to the 10th century; in the 18th century its development was boosted by the works of Mikhail Lomonosov and Denis Fonvizin, and by the early 19th century a modern native tradition had emerged, producing some of the greatest writers of all time. This period and the Golden Age of Russian Poetry began with Alexander Pushkin, considered to be the founder of modern Russian literature and often described as the "Russian Shakespeare" or the "Russian Goethe".[36] It continued in the 19th century with the poetry of Mikhail Lermontov and Nikolay Nekrasov, dramas of Aleksandr Ostrovsky and Anton Chekhov, and the prose of Nikolai Gogol, Ivan Turgenev, Leo Tolstoy, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin, Ivan Goncharov, Aleksey Pisemsky and Nikolai Leskov. Tolstoy and Dostoevsky in particular were titanic figures, to the point that many literary critics have described one or the other as the greatest novelist ever.[37][38]

By the 1880s Russian literature had begun to change. The age of the great novelists was over and short fiction and poetry became the dominant genres of Russian literature for the next several decades, which later became known as the Silver Age of Russian Poetry. Previously dominated by realism, Russian literature came under strong influence of symbolism in the years between 1893 and 1914. Leading writers of this age include Valery Bryusov, Andrei Bely, Vyacheslav Ivanov, Aleksandr Blok, Nikolay Gumilev, Dmitry Merezhkovsky, Fyodor Sologub, Anna Akhmatova, Osip Mandelstam, Marina Tsvetaeva, Leonid Andreyev, Ivan Bunin, and Maxim Gorky.

Following the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the ensuing civil war, Russian cultural life was left in chaos. Some prominent writers, like Ivan Bunin and Vladimir Nabokov left the country, while a new generation of talented writers joined in different organizations with the aim of creating a new and distinctive working-class culture appropriate for the new state, the Soviet Union. Throughout the 1920s writers enjoyed broad tolerance. In the 1930s censorship over literature was tightened in line with Joseph Stalin's policy of socialist realism. After his death the restrictions on literature were eased, and by the 1970s and 1980s, writers were increasingly ignoring official guidelines. The leading authors of the Soviet era included Yevgeny Zamiatin, Isaac Babel, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Ilf and Petrov, Yury Olesha, Mikhail Bulgakov, Boris Pasternak, Mikhail Sholokhov, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Yevgeny Yevtushenko, Vasily Grossman and Andrey Voznesensky.

The Soviet era was also the golden age of Russian science fiction, that was initially inspired by western authors and enthusiastically developed with the success of Soviet space program. Authors like Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, Kir Bulychev, Ivan Yefremov, Alexander Belyaev enjoyed mainstream popularity at the time. An important theme of Russian literature has always been the Russian soul.

Pushkin

(1799–1837)Lermontov

(1814–1841)Turgenev

(1818–1883)Dostoevsky

(1821–1881)Tolstoy

(1828–1910)Chekhov

(1860–1904)Bulgakov

(1891–1940)Akhmatova

(1889–1966)

Philosophy[edit source]

Main article: List of Russian philosophers

Some Russian writers, like Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky, are known also as philosophers, while many more authors are known primarily for their philosophical works.

Russian philosophy blossomed since the 19th century, when it was defined initially by the opposition of Westernizers, advocating Russia's following the Western political and economical models, and Slavophiles, insisting on developing Russia as a unique civilization. The latter group includes Nikolai Danilevsky and Konstantin Leontiev, the early founders of eurasianism.

In its further developments, Russian philosophy was always marked by a deep connection to literature and interest in creativity, society, politics and nationalism; cosmos and religion were other primary subjects.

In its further developments, Russian philosophy was always marked by a deep connection to literature and interest in creativity, society, politics and nationalism; cosmos and religion were other primary subjects.

Notable philosophers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries include Vladimir Solovyov, Sergei Bulgakov, Pavel Florensky, Nikolai Berdyaev, Vladimir Lossky and Vladimir Vernadsky. In the 20th century Russian philosophy became dominated by Marxism.

Bakunin

(1814–1876)Blavatsky

(1831–1891)Kropotkin

(1842–1921)Solovyov

(1853–1900)Shestov

(1866–1938)Berdyaev

(1874–1948)Roerich

(1874–1947)

Humour[edit source]

Main articles: Russian humour, Russian jokes, and Chastushka

Russia owes much of its wit to the great flexibility and richness of the Russian language, allowing for puns and unexpected associations. As with any other nation, its vast scope ranges from lewd jokes and silly word play to political satire.

Russian jokes, the most popular form of Russian humour, are short fictional stories or dialogues with a punch line. Russian joke culture features a series of categories with fixed and highly familiar settings and characters. Surprising effects are achieved by an endless variety of plots. Russians love jokes on topics found everywhere in the world, be it politics, spouse relations, or mothers-in-law.

Chastushka, a type of traditional Russian poetry, is a single quatrain in trochaic tetrameter with an "abab" or "abcb" rhyme scheme. Usually humorous, satirical, or ironic in nature, chastushkas are often put to music as well, usually with balalaika or accordion accompaniment. The rigid, short structure (and to a lesser degree, the type of humor these use) parallels limericks. The name originates from the Russian word части́ть, meaning "to speak fast".

Bakunin

(1814–1876)Blavatsky

(1831–1891)Kropotkin

(1842–1921)Solovyov

(1853–1900)Shestov

(1866–1938)Berdyaev

(1874–1948)Roerich

(1874–1947)

Humour[edit source]

Main articles: Russian humour, Russian jokes, and Chastushka

Russia owes much of its wit to the great flexibility and richness of the Russian language, allowing for puns and unexpected associations. As with any other nation, its vast scope ranges from lewd jokes and silly word play to political satire.

Russian jokes, the most popular form of Russian humour, are short fictional stories or dialogues with a punch line. Russian joke culture features a series of categories with fixed and highly familiar settings and characters. Surprising effects are achieved by an endless variety of plots. Russians love jokes on topics found everywhere in the world, be it politics, spouse relations, or mothers-in-law.

Chastushka, a type of traditional Russian poetry, is a single quatrain in trochaic tetrameter with an "abab" or "abcb" rhyme scheme. Usually humorous, satirical, or ironic in nature, chastushkas are often put to music as well, usually with balalaika or accordion accompaniment. The rigid, short structure (and to a lesser degree, the type of humor these use) parallels limericks. The name originates from the Russian word части́ть, meaning "to speak fast".