심상

심상(心象, imagery)은 상상력에 의하여 마음에 떠오르는 영상이나 정경, 어느 것들에 대해 품는 전반적인 느낌 또는 마음속에 그리는 것이다. 또한 어떤 객체, 사건 또는 정경 등을 인식하는 경험과 매우 비슷하지만, 대상이 되는 그 객체, 사건, 또는 정경이 감각에서 현전하지 않는 경험을 말한다.[1][2][3][4] 이런 경험의 본질과 무엇이 이런 경험을 가능하게 하고 있는지, 또한 이 경험에 기능이 존재하는 경우, 그들은 무엇인지는 수년에 걸쳐, 철학, 심리학, 인지 과학, 더욱 최근에는 신경 과학의 연구와 토론의 주제였다.

심상이란[편집]

현대의 연구자들이 이 같은 경험에 대해 심상은 지각의 어떤 방식에서도 일어날 수 있다고 말하고 있기에, 사람은 청각 이미지[5], 후각 이미지[6] 등의 여러 심상을 경험할 수 있다. 하지만 이 문제에 대한 철학적 및 과학적 연구의 거의 대부분은 "시각" 이미지를 중심 주제로 하고 있다. 인류 뿐만 아니라 다양한 종류의 동물들이 또한 심상을 경험하는 능력을 가진 것으로 널리 추정되고 있다. 그러나 이 현상의 근본적으로 주관적인 성질 때문에, 이 추정을 지지하는 증거도 반박할 증거도 찾아 볼 수 없다.

버클리, 흄과 같은 철학자나, 분트 및 제임스와 같은 초기의 경험주의 심리학자들은 일반적으로 관념이 심상이라고 생각하고 있었다. 오늘에 있어서는, 심상은 심적 표상으로서 작동해, 기억과 사고에서 중요한 역할을 한다고 널리 퍼져 있다.[7][8][9][10]

실제로 어느 연구자는, 심상이란 "정의로 보아" 내적으로, 심적 또는 신경적 표상의 형식으로 이해하는 것이 가장 타당하다는 제안까지 이르고 있다.[11][12] 하지만 다른 연구자는, 심상의 지각 경험이란, 마음 또는 대뇌에서의 이런 표상과 어떤 의미로도 다르며, 이런 표상에서 직접 이끌리는 것도 아니라 주장하고 있다.[13][14][15][16][17][18]

대뇌 구성[편집]

우리는 독서를 할 때 뭔가의 사건에 대해 심상이 파악된 듯이 느끼는 것은 왜인지 궁금할 때가 있다. 또한 백일몽을 꾸고 있던 경우에도 의문이 생긴다. 이런 경험에서 얻을 수 있는 심상은 마치 머릿속에 그림이 있는 것으로 보인다. 예를 들어, 음악가가 노래를 듣는 경우, 때로는 머리 속에서 노래의 "음표"가 보일 수 있다. 이는 잔상과는 다르다. 예를 들어, 어떤 사건으로부터 유도된 잔상은 의식적인 제어 권한은 없다고 생각된다. 그러나 상상에서, 또는 마음 속에서 심상을 상기할 경우 심상은 의지의 자유가 되는 것으로 생각된다. 그러므로, 심상은 여러 의식적 지배의 정도를 가진 것이 특징이다.

어느 생물학자들에 따르면, 우리는 환경 세계에 대한 경험을 심상으로 축적하고 있으며, 심상은 다른 심상과 연합되거나 비교되고 이렇게 완전히 새로운 심상이 합성된 것이라고 한다. 예를 들어, 꿈을 꾸고, 상상력을 쓸 때 이런 일이 일어난다. 이 이론은 이런 과정을 통해 우리는 세계가 어떻게 작동하는지에 대한 유용한 이론을 심상의 적절한 연속에 따라 구성하는 것이 가능하게 되고, 이 기구는 추론·연역 또는 모의 과정을 통해 얻은 결과 등을 직접 경험하지 않아도 성립된다고 주장한다. 인간 이외의 생물이 이런 능력을 가지고 있는지 여부는 논의되고 있다.

철학의 해석[편집]

심상은 지식의 연구에 있어서 필수의 문제이기에 예나 지금이나 철학에서 중요한 주제이다. "국가" 제7권에서 플라톤은 동굴의 우화를 쓰고 있다. 죄수가 묶여 꼼짝할 수 없는 상태에서 광원인 불을 등지고 앉아 그의 앞에 있는 벽을 보고 있다. 그들은 사람들이 그의 뒤에 싣고 오는 다양한 물체가 투영된 그림자를 볼 것이다. 사람들이 싣고 오는 물체는 세계 속에 존재하는 참된 사물의 것이다. 죄수는 경험을 통해 얻은 감각 자료를 바탕으로 심상을 만드는 인간을 닮았다고 소크라테스는 설명한다.

더 나중에는 조지 버클리가 그 관념론의 이론에서 비슷한 생각을 주장하고 있다. 버클리는, 실재는 심상과 동일하다 - 우리가 품는 심상은 다른 물질적 존재의 복사가 아니라 실재 그 자체라고 말했다. 하지만 버클리는 그가 외부 세계를 구성한다고 보는 심상과, 개인의 상상력이 만들어내는 심상을 명확하게 구분했다. 버클리에 따르면 후자만이 오늘의 용어법의 의미에서의 "심상"으로 간주된다.

18세기 영국의 문필가인 새뮤얼 존슨은 관념론을 비판하고 있다. 스코틀랜드에서 야외를 산책하고 있던 때, 관념론의 장단점에 대해 질문을 받은 그는 단언해서 다음과 같이 대답했다. "어쨌든, 그런 것은 부정한다" 존슨은 옆의 큰 바위를 다리로 걷어차, 다리가 튀는 걸 보이며 말했다. 그의 주장의 요점은 바위가 심상이며, 그 자신의 물질적 실재가 없다는 개념, 생각, 발상은 그가 바로 바위를 걷어차서 경험한 고통의 감각 자료의 설명으로 타당하지 않다는 것이다.

같이 보기[편집]

출처[편집]

- ↑ McKellar, 1957년

- ↑ Richardson, 1969년

- ↑ Finke, 1989년

- ↑ Thomas, 2003년

- ↑ Reisberg, 1992년

- ↑ Bensafi et al., 2003년

- ↑ Allan Paivio, 1986년

- ↑ Kieran Egan, 1992년

- ↑ Lawrence W. Barsalou, 1999년

- ↑ Prinz, 2002년

- ↑ Ned Block, 1983년

- ↑ Stephen Kosslyn, 1983년

- ↑ 장폴 사르트르, 1940년

- ↑ 길버트 라일, 1949년

- ↑ B. F. 스키너, 1974년

- ↑ Thomas, 1999년

- ↑ Bartolomeo, 2002년

- ↑ Bennett & Hacker, 2003년

참고 도서[편집]

- Amorim, Michel-Ange, Brice Isableu and Mohammed Jarraya (2006) Embodied Spatial Transformations: “Body Analogy” for the Mental Rotation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General.

- Barsalou, L.W. (1999). “Perceptual Symbol Systems”. 《Behavioral and Brain Sciences》 22 (4): 577–660. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.601.93. doi:10.1017/s0140525x99002149. PMID 11301525.

- Bartolomeo, P (2002). “The Relationship Between Visual perception and Visual Mental Imagery: A Reappraisal of the Neuropsychological Evidence”. 《Cortex》 38 (3): 357–378. doi:10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70665-8. PMID 12146661.

- Bennett, M.R. & Hacker, P.M.S. (2003). Philosophical Foundations of Neuroscience. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Bensafi, M.; Porter, J.; Pouliot, S.; Mainland, J.; Johnson, B.; Zelano, C.; Young, N.; Bremner, E.; Aframian, D.; Kahn, R.; Sobel, N. (2003). “Olfactomotor Activity During Imagery Mimics that During Perception”. 《Nature Neuroscience》 6 (11): 1142–1144. doi:10.1038/nn1145. PMID 14566343.

- Block, N (1983). “Mental Pictures and Cognitive Science”. 《Philosophical Review》 92 (4): 499–539. doi:10.2307/2184879. JSTOR 2184879.

- Brant, W. (2013). Mental Imagery and Creativity: Cognition, Observation and Realization. Akademikerverlag. pp. 227. Saarbrücken, Germany. ISBN 978-3-639-46288-3

- Cui, X.; Jeter, C.B.; Yang, D.; Montague, P.R.; Eagleman, D.M. (2007). “Vividness of mental imagery: Individual variability can be measured objectively”. 《Vision Research》 47 (4): 474–478. doi:10.1016/j.visres.2006.11.013. PMC 1839967. PMID 17239915.

- Deutsch, David (1998). 《The Fabric of Reality》. ISBN 978-0-14-014690-5.

- Egan, Kieran (1992). Imagination in Teaching and Learning. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Fichter, C.; Jonas, K. (2008). “Image Effects of Newspapers. How Brand Images Change Consumers' Product Ratings”. 《Zeitschrift für Psychologie》 216 (4): 226–234. doi:10.1027/0044-3409.216.4.226. 2013년 1월 3일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- Finke, R.A. (1989). Principles of Mental Imagery. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Garnder, Howard. (1987) The Mind's New Science: A History of the Cognitive Revolution New York: Basic Books.

- Gur, R.C.; Hilgard, E.R. (1975). “Visual imagery and discrimination of differences between altered pictures simultaneously and successively presented”. 《British Journal of Psychology》 66 (3): 341–345. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8295.1975.tb01470.x. PMID 1182401.

- Kosslyn, Stephen M. (1983). Ghosts in the Mind's Machine: Creating and Using Images in the Brain. New York: Norton.

- Kosslyn, Stephen (1994) Image and Brain: The Resolution of the Imagery Debate. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Kosslyn, Stephen M.; Thompson, William L.; Kim, Irene J.; Alpert, Nathaniel M. (1995). “Topographic representations of mental images in primary visual cortex”. 《Nature》 378 (6556): 496–498. Bibcode:1995Natur.378..496K. doi:10.1038/378496a0. PMID 7477406.

- Kosslyn, Stephen M.; Thompson, William L.; Wraga, Mary J.; Alpert, Nathaniel M. (2001). “Imagining rotation by endogenous versus exogenous forces: Distinct neural mechanisms”. 《NeuroReport》 12 (11): 2519–2525. doi:10.1097/00001756-200108080-00046. PMID 11496141.

- Logie, R.H.; Pernet, C.R.; Buonocore, A.; Della Sala, S. (2011). “Low and high imagers activate networks differentially in mental rotation”. 《Neuropsychologia》 49 (11): 3071–3077. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.07.011. PMID 21802436.

- Marks, D.F. (1973). “Visual imagery differences in the recall of pictures”. 《British Journal of Psychology》 64 (1): 17–24. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8295.1973.tb01322.x. PMID 4742442.

- Marks, D.F. (1995). “New directions for mental imagery research”. 《Journal of Mental Imagery》 19: 153–167.

- McGabhann. R, Squires. B, 2003, 'Releasing The Beast Within – A path to Mental Toughness', Granite Publishing, Australia.

- McKellar, Peter (1957). Imagination and Thinking. London: Cohen & West.

- Norman, Donald. 《The Design of Everyday Things》. ISBN 978-0-465-06710-7.

- Paivio, Allan (1986). Mental Representations: A Dual Coding Approach. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Parsons, Lawrence M (1987). “Imagined spatial transformations of one's hands and feet”. 《Cognitive Psychology》 19 (2): 178–241. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(87)90011-9. PMID 3581757.

- Parsons, Lawrence M (2003). “Superior parietal cortices and varieties of mental rotation”. 《Trends in Cognitive Sciences》 7 (12): 515–551. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2003.10.002. PMID 14643362.

- Pascual-Leone, Alvaro, Nguyet Dang, Leonardo G. Cohen, Joaquim P. Brasil-Neto, Angel Cammarota, and Mark Hallett (1995). Modulation of Muscle Responses Evoked by Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation During the Acquisition of New Fine Motor Skills. Journal of Neuroscience [1]

- Plato (2000). 《The Republic (New CUP translation into English)》. ISBN 978-0-521-48443-5.

- Plato (2003). 《Respublica (New CUP edition of Greek text)》. ISBN 978-0-19-924849-0.

- Prinz, J.J. (2002). Furnishing the Mind: Concepts and their Perceptual Basis. Boston, MA: MIT Press.

- Pylyshyn, Zenon W (1973). “What the mind's eye tells the mind's brain: a critique of mental imagery”. 《Psychological Bulletin》 80: 1–24. doi:10.1037/h0034650.

- Reisberg, Daniel (Ed.) (1992). Auditory Imagery. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Richardson, A. (1969). Mental Imagery. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Rodway, P.; Gillies, K.; Schepman, A. (2006). “Vivid imagers are better at detecting salient changes”. 《Journal of Individual Differences》 27 (4): 218–228. doi:10.1027/1614-0001.27.4.218.

- Rohrer, T. (2006). The Body in Space: Dimensions of embodiment The Body in Space: Embodiment, Experientialism and Linguistic Conceptualization. In Body, Language and Mind, vol. 2. Zlatev, Jordan; Ziemke, Tom; Frank, Roz; Dirven, René (eds.). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Ryle, G. (1949). The Concept of Mind. London: Hutchinson.

- Sartre, J.-P. (1940). The Psychology of Imagination. (Translated from the French by B. Frechtman, New York: Philosophical Library, 1948.)

- Schwoebel, John; Friedman, Robert; Duda, Nanci; Coslett, H. Branch (2001). “Pain and the body schema evidence for peripheral effects on mental representations of movement”. 《Brain》 124 (10): 2098–2104. doi:10.1093/brain/124.10.2098. PMID 11571225.

- Skinner, B.F. (1974). About Behaviorism. New York: Knopf.

- Shepard, Roger N.; Metzler, Jacqueline (1971). “Mental rotation of three-dimensional objects”. 《Science》 171 (3972): 701–703. Bibcode:1971Sci...171..701S. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.610.4345. doi:10.1126/science.171.3972.701. PMID 5540314.

- Thomas, Nigel J.T. (1999). “Are Theories of Imagery Theories of Imagination? An Active Perception Approach to Conscious Mental Content”. 《Cognitive Science》 23 (2): 207–245. doi:10.1207/s15516709cog2302_3. 2008년 2월 21일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- Thomas, N.J.T. (2003). Mental Imagery, Philosophical Issues About. In L. Nadel (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science (Volume 2, pp. 1147–1153). London: Nature Publishing/Macmillan.

- Traill, R.R. (2015). Concurrent Roles for the Eye Concurrent Roles for the Eye (Passive 'Camera' plus Active Decoder) – Hence Separate Mechanisms?, Melbourne: Ondwelle Publications.

외부 링크[편집]

| 위키인용집에 이 문서와 관련된 문서가 있습니다. |

Mental image

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2010) |

A mental image is an experience that, on most occasions, significantly resembles the experience of 'perceiving' some object, event, or scene, but occurs when the relevant object, event, or scene is not actually present to the senses.[1][2][3][4] There are sometimes episodes, particularly on falling asleep (hypnagogic imagery) and waking up (hypnopompic), when the mental imagery, being of a rapid, phantasmagoric and involuntary character, defies perception, presenting a kaleidoscopic field, in which no distinct object can be discerned.[5] Mental imagery can sometimes produce the same effects as would be produced by the behavior or experience imagined.[6]

The nature of these experiences, what makes them possible, and their function (if any) have long been subjects of research and controversy in philosophy, psychology, cognitive science, and, more recently, neuroscience. As contemporary researchers use the expression, mental images or imagery can comprise information from any source of sensory input; one may experience auditory images,[7] olfactory images,[8] and so forth. However, the majority of philosophical and scientific investigations of the topic focus upon visual mental imagery. It has sometimes been assumed that, like humans, some types of animals are capable of experiencing mental images.[9] Due to the fundamentally introspective nature of the phenomenon, it has been difficult to assess whether or not non-human animals experience mental imagery.

Philosophers such as George Berkeley and David Hume, and early experimental psychologists such as Wilhelm Wundt and William James, understood ideas in general to be mental images. Today it is very widely believed that much imagery functions as mental representations (or mental models), playing an important role in memory and thinking.[10][11][12][13] William Brant (2013, p. 12) traces the scientific use of the phrase "mental images" back to John Tyndall's 1870 speech called the "Scientific Use of the Imagination". Some have gone so far as to suggest that images are best understood to be, by definition, a form of inner, mental or neural representation;[14][15] in the case of hypnagogic and hypnapompic imagery, it is not representational at all. Others reject the view that the image experience may be identical with (or directly caused by) any such representation in the mind or the brain,[16][17][18][19][20][21] but do not take account of the non-representational forms of imagery.

The mind's eye[edit]

The notion of a "mind's eye" goes back at least to Cicero's reference to mentis oculi during his discussion of the orator's appropriate use of simile.[22]

In this discussion, Cicero observed that allusions to "the Syrtis of his patrimony" and "the Charybdis of his possessions" involved similes that were "too far-fetched"; and he advised the orator to, instead, just speak of "the rock" and "the gulf" (respectively)—on the grounds that "the eyes of the mind are more easily directed to those objects which we have seen, than to those which we have only heard".[23]

The concept of "the mind's eye" first appeared in English in Chaucer's (c. 1387) Man of Law's Tale in his Canterbury Tales, where he tells us that one of the three men dwelling in a castle was blind, and could only see with "the eyes of his mind"; namely, those eyes "with which all men see after they have become blind".[24]

Physical basis[edit]

The biological foundation of the mind's eye is not fully understood. Studies using fMRI have shown that the lateral geniculate nucleus and the V1 area of the visual cortex are activated during mental imagery tasks.[25] Ratey writes:

The rudiments of a biological basis for the mind's eye is found in the deeper portions of the brain below the neocortex, or where the center of perception exists. The thalamus has been found to be discrete to other components in that it processes all forms of perceptional data relayed from both lower and higher components of the brain. Damage to this component can produce permanent perceptual damage, however when damage is inflicted upon the cerebral cortex, the brain adapts to neuroplasticity to amend any occlusions for perception[citation needed]. It can be thought that the neocortex is a sophisticated memory storage warehouse in which data received as an input from sensory systems are compartmentalized via the cerebral cortex. This would essentially allow for shapes to be identified, although given the lack of filtering input produced internally, one may as a consequence, hallucinate—essentially seeing something that isn't received as an input externally but rather internal (i.e. an error in the filtering of segmented sensory data from the cerebral cortex may result in one seeing, feeling, hearing or experiencing something that is inconsistent with reality).

Not all people have the same internal perceptual ability. For many, when the eyes are closed, the perception of darkness prevails. However, some people are able to perceive colorful, dynamic imagery.[citation needed] The use of hallucinogenic drugs increases the subject's ability to consciously access visual (and auditory, and other sense) percepts.[citation needed]

Furthermore, the pineal gland is a hypothetical candidate for producing a mind's eye. Rick Strassman and others have postulated that during near-death experiences (NDEs) and dreaming, the gland might secrete a hallucinogenic chemical N,N-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT) to produce internal visuals when external sensory data is occluded.[27] However, this hypothesis has yet to be fully supported with neurochemical evidence and plausible mechanism for DMT production.

The condition where a person lacks mental imagery is called aphantasia. The term was first suggested in a 2015 study.[28]

Common examples of mental images include daydreaming and the mental visualization that occurs while reading a book. Another is of the pictures summoned by athletes during training or before a competition, outlining each step they will take to accomplish their goal.[29] When a musician hears a song, they can sometimes "see" the song notes in their head, as well as hear them with all their tonal qualities.[30] This is considered different from an after-effect, such as an afterimage. Calling up an image in our minds can be a voluntary act, so it can be characterized as being under various degrees of conscious control.

According to psychologist and cognitive scientist Steven Pinker,[31] our experiences of the world are represented in our minds as mental images. These mental images can then be associated and compared with others, and can be used to synthesize completely new images. In this view, mental images allow us to form useful theories of how the world works by formulating likely sequences of mental images in our heads without having to directly experience that outcome. Whether other creatures have this capability is debatable.

There are several theories as to how mental images are formed in the mind. These include the dual-code theory, the propositional theory, and the functional-equivalency hypothesis. The dual-code theory, created by Allan Paivio in 1971, is the theory that we use two separate codes to represent information in our brains: image codes and verbal codes. Image codes are things like thinking of a picture of a dog when you are thinking of a dog, whereas a verbal code would be to think of the word "dog".[32] Another example is the difference between thinking of abstract words such as justice or love and thinking of concrete words like elephant or chair. When abstract words are thought of, it is easier to think of them in terms of verbal codes—finding words that define them or describe them. With concrete words, it is often easier to use image codes and bring up a picture of a human or chair in your mind rather than words associated or descriptive of them.

The propositional theory involves storing images in the form of a generic propositional code that stores the meaning of the concept not the image itself. The propositional codes can either be descriptive of the image or symbolic. They are then transferred back into verbal and visual code to form the mental image.[33]

The functional-equivalency hypothesis is that mental images are "internal representations" that work in the same way as the actual perception of physical objects.[34] In other words, the picture of a dog brought to mind when the word dog is read is interpreted in the same way as if the person looking at an actual dog before them.

Research has occurred to designate a specific neural correlate of imagery; however, studies show a multitude of results. Most studies published before 2001 suggest neural correlates of visual imagery occur in Brodmann area 17.[35] Auditory performance imagery have been observed in the premotor areas, precunes, and medial Brodmann area 40.[36] Auditory imagery in general occurs across participants in the temporal voice area (TVA), which allows top-down imaging manipulations, processing, and storage of audition functions.[37] Olfactory imagery research shows activation in the anterior piriform cortex and the posterior piriform cortex; experts in olfactory imagery have larger gray matter associated to olfactory areas.[38] Tactile imagery is found to occur in the dorsolateral prefrontal area, inferior frontal gyrus, frontal gyrus, insula, precentral gyrus, and the medial frontal gyrus with basal ganglia activation in the ventral posteriomedial nucleus and putamen (hemisphere activation corresponds to the location of the imagined tactile stimulus).[39] Research in gustatory imagery reveals activation in the anterior insular cortex, frontal operculum, and prefrontal cortex.[35] Novices of a specific form of mental imagery show less gray matter than experts of mental imagery congruent to that form.[40] A meta-analysis of neuroimagery studies revealed significant activation of the bilateral dorsal parietal, interior insula, and left inferior frontal regions of the brain.[41]

Imagery has been thought to cooccur with perception; however, participants with damaged sense-modality receptors can sometimes perform imagery of said modality receptors.[42] Neuroscience with imagery has been used to communicate with seemingly unconscious individuals through fMRI activation of different neural correlates of imagery, demanding further study into low quality consciousness.[43] A study on one patient with one occipital lobe removed found the horizontal area of their visual mental image was reduced.[44]

Neural substrates of visual imagery[edit]

Visual imagery is the ability to create mental representations of things, people, and places that are absent from an individual’s visual field. This ability is crucial to problem-solving tasks, memory, and spatial reasoning.[45] Neuroscientists have found that imagery and perception share many of the same neural substrates, or areas of the brain that function similarly during both imagery and perception, such as the visual cortex and higher visual areas. Kosslyn and colleagues (1999)[46] showed that the early visual cortex, Area 17 and Area 18/19, is activated during visual imagery. They found that inhibition of these areas through repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) resulted in impaired visual perception and imagery. Furthermore, research conducted with lesioned patients has revealed that visual imagery and visual perception have the same representational organization. This has been concluded from patients in which impaired perception also experience visual imagery deficits at the same level of the mental representation.[47]

Behrmann and colleagues (1992)[48] describe a patient C.K., who provided evidence challenging the view that visual imagery and visual perception rely on the same representational system. C.K. was a 33-year old man with visual object agnosia acquired after a vehicular accident. This deficit prevented him from being able to recognize objects and copy objects fluidly. Surprisingly, his ability to draw accurate objects from memory indicated his visual imagery was intact and normal. Furthermore, C.K. successfully performed other tasks requiring visual imagery for judgment of size, shape, color, and composition. These findings conflict with previous research as they suggest there is a partial dissociation between visual imagery and visual perception. C.K. exhibited a perceptual deficit that was not associated with a corresponding deficit in visual imagery, indicating that these two processes have systems for mental representations that may not be mediated entirely by the same neural substrates.

Schlegel and colleagues (2013)[49] conducted a functional MRI analysis of regions activated during manipulation of visual imagery. They identified 11 bilateral cortical and subcortical regions that exhibited increased activation when manipulating a visual image compared to when the visual image was just maintained. These regions included the occipital lobe and ventral stream areas, two parietal lobe regions, the posterior parietal cortex and the precuneus lobule, and three frontal lobe regions, the frontal eye fields, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and the prefrontal cortex. Due to their suspected involvement in working memory and attention, the authors propose that these parietal and prefrontal regions, and occipital regions, are part of a network involved in mediating the manipulation of visual imagery. These results suggest a top-down activation of visual areas in visual imagery.[50]

Using Dynamic Causal Modeling (DCM) to determine the connectivity of cortical networks, Ishai et al. (2010)[51] demonstrated that activation of the network mediating visual imagery is initiated by prefrontal cortex and posterior parietal cortex activity. Generation of objects from memory resulted in initial activation of the prefrontal and the posterior parietal areas, which then activate earlier visual areas through backward connectivity. Activation of the prefrontal cortex and posterior parietal cortex has also been found to be involved in retrieval of object representations from long-term memory, their maintenance in working memory, and attention during visual imagery. Thus, Ishai et al. suggest that the network mediating visual imagery is composed of attentional mechanisms arising from the posterior parietal cortex and the prefrontal cortex.

Vividness of visual imagery is a crucial component of an individual’s ability to perform cognitive tasks requiring imagery. Vividness of visual imagery varies not only between individuals but also within individuals. Dijkstra and colleagues (2017)[45] found that the variation in vividness of visual imagery is dependent on the degree to which the neural substrates of visual imagery overlap with those of visual perception. They found that overlap between imagery and perception in the entire visual cortex, the parietal precuneus lobule, the right parietal cortex, and the medial frontal cortex predicted the vividness of a mental representation. The activated regions beyond the visual areas are believed to drive the imagery-specific processes rather than the visual processes shared with perception. It has been suggested that the precuneus contributes to vividness by selecting important details for imagery. The medial frontal cortex is suspected to be involved in the retrieval and integration of information from the parietal and visual areas during working memory and visual imagery. The right parietal cortex appears to be important in attention, visual inspection, and stabilization of mental representations. Thus, the neural substrates of visual imagery and perception overlap in areas beyond the visual cortex and the degree of this overlap in these areas correlates with the vividness of mental representations during imagery.

Philosophical ideas[edit]

Mental images are an important topic in classical and modern philosophy, as they are central to the study of knowledge. In the Republic, Book VII, Plato has Socrates present the Allegory of the Cave: a prisoner, bound and unable to move, sits with his back to a fire watching the shadows cast on the cave wall in front of him by people carrying objects behind his back. These people and the objects they carry are representations of real things in the world. Unenlightened man is like the prisoner, explains Socrates, a human being making mental images from the sense data that he experiences.

The eighteenth-century philosopher Bishop George Berkeley proposed similar ideas in his theory of idealism. Berkeley stated that reality is equivalent to mental images—our mental images are not a copy of another material reality but that reality itself. Berkeley, however, sharply distinguished between the images that he considered to constitute the external world, and the images of individual imagination. According to Berkeley, only the latter are considered "mental imagery" in the contemporary sense of the term.

The eighteenth century British writer Dr. Samuel Johnson criticized idealism. When asked what he thought about idealism, he is alleged to have replied "I refute it thus!"[52] as he kicked a large rock and his leg rebounded. His point was that the idea that the rock is just another mental image and has no material existence of its own is a poor explanation of the painful sense data he had just experienced.

David Deutsch addresses Johnson's objection to idealism in The Fabric of Reality when he states that, if we judge the value of our mental images of the world by the quality and quantity of the sense data that they can explain, then the most valuable mental image—or theory—that we currently have is that the world has a real independent existence and that humans have successfully evolved by building up and adapting patterns of mental images to explain it. This is an important idea in scientific thought.[why?]

Critics of scientific realism ask how the inner perception of mental images actually occurs. This is sometimes called the "homunculus problem" (see also the mind's eye). The problem is similar to asking how the images you see on a computer screen exist in the memory of the computer. To scientific materialism, mental images and the perception of them must be brain-states. According to critics,[who?] scientific realists cannot explain where the images and their perceiver exist in the brain. To use the analogy of the computer screen, these critics argue that cognitive science and psychology have been unsuccessful in identifying either the component in the brain (i.e., "hardware") or the mental processes that store these images (i.e. "software").

In experimental psychology[edit]

Cognitive psychologists and (later) cognitive neuroscientists have empirically tested some of the philosophical questions related to whether and how the human brain uses mental imagery in cognition.

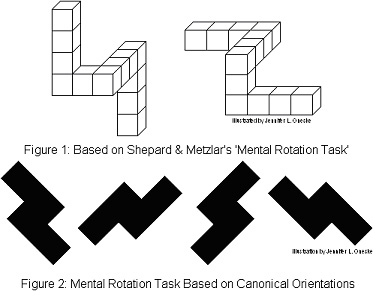

One theory of the mind that was examined in these experiments was the "brain as serial computer" philosophical metaphor of the 1970s. Psychologist Zenon Pylyshyn theorized that the human mind processes mental images by decomposing them into an underlying mathematical proposition. Roger Shepard and Jacqueline Metzler challenged that view by presenting subjects with 2D line drawings of groups of 3D block "objects" and asking them to determine whether that "object" is the same as a second figure, some of which rotations of the first "object".[53] Shepard and Metzler proposed that if we decomposed and then mentally re-imaged the objects into basic mathematical propositions, as the then-dominant view of cognition "as a serial digital computer"[54] assumed, then it would be expected that the time it took to determine whether the object is the same or not would be independent of how much the object had been rotated. Shepard and Metzler found the opposite: a linear relationship between the degree of rotation in the mental imagery task and the time it took participants to reach their answer.

This mental rotation finding implied that the human mind—and the human brain—maintains and manipulates mental images as topographic and topological wholes, an implication that was quickly put to test by psychologists. Stephen Kosslyn and colleagues[55] showed in a series of neuroimaging experiments that the mental image of objects like the letter "F" are mapped, maintained and rotated as an image-like whole in areas of the human visual cortex. Moreover, Kosslyn's work showed that there are considerable similarities between the neural mappings for imagined stimuli and perceived stimuli. The authors of these studies concluded that, while the neural processes they studied rely on mathematical and computational underpinnings, the brain also seems optimized to handle the sort of mathematics that constantly computes a series of topologically-based images rather than calculating a mathematical model of an object.

Recent studies in neurology and neuropsychology on mental imagery have further questioned the "mind as serial computer" theory, arguing instead that human mental imagery manifests both visually and kinesthetically. For example, several studies have provided evidence that people are slower at rotating line drawings of objects such as hands in directions incompatible with the joints of the human body,[56] and that patients with painful, injured arms are slower at mentally rotating line drawings of the hand from the side of the injured arm.[57]

Some psychologists, including Kosslyn, have argued that such results occur because of interference in the brain between distinct systems in the brain that process the visual and motor mental imagery. Subsequent neuroimaging studies[58] showed that the interference between the motor and visual imagery system could be induced by having participants physically handle actual 3D blocks glued together to form objects similar to those depicted in the line-drawings. Amorim et al. have shown that, when a cylindrical "head" was added to Shepard and Metzler's line drawings of 3D block figures, participants were quicker and more accurate at solving mental rotation problems.[59] They argue that motoric embodiment is not just "interference" that inhibits visual mental imagery but is capable of facilitating mental imagery.

As cognitive neuroscience approaches to mental imagery continued, research expanded beyond questions of serial versus parallel or topographic processing to questions of the relationship between mental images and perceptual representations. Both brain imaging (fMRI and ERP) and studies of neuropsychological patients have been used to test the hypothesis that a mental image is the reactivation, from memory, of brain representations normally activated during the perception of an external stimulus. In other words, if perceiving an apple activates contour and location and shape and color representations in the brain’s visual system, then imagining an apple activates some or all of these same representations using information stored in memory. Early evidence for this idea came from neuropsychology. Patients with brain damage that impairs perception in specific ways, for example by damaging shape or color representations, seem to generally to have impaired mental imagery in similar ways.[60] Studies of brain function in normal human brains support this same conclusion, showing activity in the brain’s visual areas while subjects imagined visual objects and scenes.[61]

The previously mentioned and numerous related studies have led to a relative consensus within cognitive science, psychology, neuroscience, and philosophy on the neural status of mental images. In general, researchers agree that, while there is no homunculus inside the head viewing these mental images, our brains do form and maintain mental images as image-like wholes.[62] The problem of exactly how these images are stored and manipulated within the human brain, in particular within language and communication, remains a fertile area of study.

One of the longest-running research topics on the mental image has basis on the fact that people report large individual differences in the vividness of their images. Special questionnaires have been developed to assess such differences, including the Vividness of Visual Imagery Questionnaire (VVIQ) developed by David Marks. Laboratory studies have suggested that the subjectively reported variations in imagery vividness are associated with different neural states within the brain and also different cognitive competences such as the ability to accurately recall information presented in pictures[63] Rodway, Gillies and Schepman used a novel long-term change detection task to determine whether participants with low and high vividness scores on the VVIQ2 showed any performance differences.[64] Rodway et al. found that high vividness participants were significantly more accurate at detecting salient changes to pictures compared to low-vividness participants.[65] This replicated an earlier study.[66]

Recent studies have found that individual differences in VVIQ scores can be used to predict changes in a person's brain while visualizing different activities.[67] Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) was used to study the association between early visual cortex activity relative to the whole brain while participants visualized themselves or another person bench pressing or stair climbing. Reported image vividness correlates significantly with the relative fMRI signal in the visual cortex. Thus, individual differences in the vividness of visual imagery can be measured objectively.

Logie, Pernet, Buonocore and Della Sala (2011) used behavioural and fMRI data for mental rotation from individuals reporting vivid and poor imagery on the VVIQ. Groups differed in brain activation patterns suggesting that the groups performed the same tasks in different ways. These findings help to explain the lack of association previously reported between VVIQ scores and mental rotation performance.

Training and learning styles[edit]

Some educational theorists[who?] have drawn from the idea of mental imagery in their studies of learning styles. Proponents of these theories state that people often have learning processes that emphasize visual, auditory, and kinesthetic systems of experience.[citation needed] According to these theorists, teaching in multiple overlapping sensory systems benefits learning, and they encourage teachers to use content and media that integrates well with the visual, auditory, and kinesthetic systems whenever possible.

Educational researchers have examined whether the experience of mental imagery affects the degree of learning. For example, imagining playing a five-finger piano exercise (mental practice) resulted in a significant improvement in performance over no mental practice—though not as significant as that produced by physical practice. The authors of the study stated that "mental practice alone seems to be sufficient to promote the modulation of neural circuits involved in the early stages of motor skill learning".[68]

Visualization and the Himalayan traditions[edit]

In general, Vajrayana Buddhism, Bön, and Tantra utilize sophisticated visualization or imaginal (in the language of Jean Houston of Transpersonal Psychology) processes in the thoughtform construction of the yidam sadhana, kye-rim, and dzog-rim modes of meditation and in the yantra, thangka, and mandala traditions, where holding the fully realized form in the mind is a prerequisite prior to creating an 'authentic' new art work that will provide a sacred support or foundation for deity.[69][70]

Substitution effects[edit]

Mental imagery can act as a substitute for the imagined experience: Imagining an experience can evoke similar cognitive, physiological, and/or behavioral consequences as having the corresponding experience in reality.[71] At least four classes of such effects have been documented.[6]

- Imagined experiences are attributed evidentiary value like physical evidence.

- Mental practice can instantiate the same performance benefits as physical practice and reduction central neuropathic pain.[72][71]

- Imagined consumption of a food can reduce its actual consumption.

- Imagined goal achievement can reduce motivation for actual goal achievement.

See also[edit]

- Aphantasia (condition whereby people can't think with mental images at all)

- Animal cognition

- Audiation (imaginary sound)

- Cognition

- Creative visualization

- Fantasy (psychology)

- Fantasy prone personality

- Guided imagery

- Imagination

- Internal monologue

- Mental event

- Mental rotation

- Mind

- Motor imagery

- Spatial ability

- Tulpa

- Visual space

- Vividness of Visual Imagery Questionnaire

References[edit]

- ^ McKellar, 1957

- ^ Richardson, 1969

- ^ Finke, 1989

- ^ Thomas, 2003

- ^ Wright, Edmond (1983). "Inspecting images". Philosophy. 58 (223): 57–72 (see pp. 68–72). doi:10.1017/s0031819100056266.

- ^ a b Kappes, Heather Barry; Morewedge, Carey K. (2016-07-01). "Mental Simulation as Substitute for Experience" (PDF). Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 10 (7): 405–420. doi:10.1111/spc3.12257. ISSN 1751-9004.

- ^ Reisberg, 1992

- ^ Bensafi et al., 2003

- ^ Aristotle: On the Soul III.3 428a

- ^ Pavio, 1986

- ^ Egan, 1992

- ^ Barsalou, 1999

- ^ Prinz, 2002

- ^ Block, 1983

- ^ Kosslyn, 1983

- ^ Sartre, 1940

- ^ Ryle, 1949

- ^ Skinner, 1974

- ^ Thomas, 1999

- ^ Bartolomeo, 2002

- ^ Bennett & Hacker, 2003

- ^ Cicero, De Oratore, Liber III: XLI: 163.

- ^ J.S. (trans. and ed.), Cicero on Oratory and Orators, Harper & Brothers, (New York), 1875: Book III, C.XLI, p. 239.

- ^ The Man of Laws Tale, lines 550–553.

- ^ Imagery of famous faces: effects of memory and attention revealed by fMRI Archived 2006-08-21 at the Wayback Machine, A. Ishai, J. V. Haxby and L. G. Ungerleider, NeuroImage 17 (2002), pp. 1729–1741.

- ^ A User's Guide to the Brain, John J. Ratey, ISBN 0-375-70107-9, at p. 107.

- ^ Rick Strassman, DMT: The Spirit Molecule: A Doctor's Revolutionary Research into the Biology of Near-Death and Mystical Experiences, 320 pages, Park Street Press, 2001, ISBN 0-89281-927-8

- ^ Zeman, Adam; Dewar, Michaela; Della Sala, Sergio (2015). "Lives without imagery – Congenital aphantasia" (PDF). Cortex. 73: 378–380. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2015.05.019. hdl:10871/17613. ISSN 0010-9452. PMID 26115582. S2CID 19224930.

- ^ Plessinger, Annie. The Effects of Mental Imagery on Athletic Performance. The Mental Edge. 12/20/13. Web. http://www.vanderbilt.edu

- ^ Sacks, Oliver (2007). Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain. London: Picador. pp. 30–40.

- ^ Pinker, S. (1999). How the Mind Works. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Paivio, Allan. 1941. Dual Coding Theory. Theories of Learning in Educational Psychology. (2013). Web. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-02-21. Retrieved 2010-06-16.

- ^ Mental Imaging Theories. 2013. Web. http://faculty.mercer.edu

- ^ Eysenck, M. W. (2012). Fundamentals of Cognition, 2nd ed. New York: Psychology Press.

- ^ a b Kobayashi, Masayuki; Sasabe, Tetsuya; Shigihara, Yoshihito; Tanaka, Masaaki; Watanabe, Yasuyoshi (2011-07-08). "Gustatory Imagery Reveals Functional Connectivity from the Prefrontal to Insular Cortices Traced with Magnetoencephalography". PLOS ONE. 6 (7): e21736. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...621736K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021736. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3132751. PMID 21760903.

- ^ Meister, I. G; Krings, T; Foltys, H; Boroojerdi, B; Müller, M; Töpper, R; Thron, A (2004-05-01). "Playing piano in the mind – an fMRI study on music imagery and performance in pianists". Cognitive Brain Research. 19 (3): 219–228. doi:10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2003.12.005. PMID 15062860.

- ^ Brück, Carolin; Kreifelts, Benjamin; Gößling-Arnold, Christina; Wertheimer, Jürgen; Wildgruber, Dirk (2014-11-01). "'Inner voices': the cerebral representation of emotional voice cues described in literary texts". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 9 (11): 1819–1827. doi:10.1093/scan/nst180. ISSN 1749-5016. PMC 4221224. PMID 24396008.

- ^ Arshamian, Artin; Larsson, Maria (2014-01-01). "Same same but different: the case of olfactory imagery". Frontiers in Psychology. 5: 34. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00034. PMC 3909946. PMID 24550862.

- ^ Yoo, Seung-Schik; Freeman, Daniel K.; McCarthy, James J. III; Jolesz, Ferenc A. (2003-03-24). "Neural substrates of tactile imagery: a functional MRI study". NeuroReport. 14 (4): 581–585. doi:10.1097/00001756-200303240-00011. PMID 12657890. S2CID 40971701.

- ^ Lima, César F.; Lavan, Nadine; Evans, Samuel; Agnew, Zarinah; Halpern, Andrea R.; Shanmugalingam, Pradheep; Meekings, Sophie; Boebinger, Dana; Ostarek, Markus (2015-11-01). "Feel the Noise: Relating Individual Differences in Auditory Imagery to the Structure and Function of Sensorimotor Systems". Cerebral Cortex. 25 (11): 4638–4650. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhv134. ISSN 1047-3211. PMC 4816805. PMID 26092220.

- ^ Mcnorgan, Chris (2012-01-01). "A meta-analytic review of multisensory imagery identifies the neural correlates of modality-specific and modality-general imagery". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 6: 285. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2012.00285. PMC 3474291. PMID 23087637.

- ^ Kosslyn, Stephen M.; Ganis, Giorgio; Thompson, William L. (2001). "Neural foundations of imagery". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2 (9): 635–642. doi:10.1038/35090055. PMID 11533731. S2CID 605234.

- ^ Gibson, Raechelle M.; Fernández-Espejo, Davinia; Gonzalez-Lara, Laura E.; Kwan, Benjamin Y.; Lee, Donald H.; Owen, Adrian M.; Cruse, Damian (2014-01-01). "Multiple tasks and neuroimaging modalities increase the likelihood of detecting covert awareness in patients with disorders of consciousness". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 8: 950. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00950. PMC 4244609. PMID 25505400.

- ^ Farah MJ; Soso MJ; Dasheiff RM (1992). "Visual angle of the mind's eye before and after unilateral occipital lobectomy". J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform. 18 (1): 241–246. doi:10.1037/0096-1523.18.1.241. PMID 1532190.

- ^ a b Dijkstra, N., Bosch, S. E., & van Gerven, M. A. J. “Vividness of Visual Imagery Depends on the Neural Overlap with Perception in Visual Areas”, The Journal of Neuroscience, 37(5), 1367 LP-1373. (2017).

- ^ Kosslyn, S. M., Pascual-Leone, A., Felician, O., Camposano, S., Keenan, J. P., L., W., … Alpert. “The Role of Area 17 in Visual Imagery: Convergent Evidence from PET and rTMS”, Science, 284(5411), 167 LP-170, (1999).

- ^ Farah, M (1988). "Is Visual Imagery Really Visual? Overlooked Evidence From Neuropsychology". Psychological Review. 95 (3): 307–317. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.95.3.307. PMID 3043530.

- ^ Behrmann, Marlene; Winocur, Gordon; Moscovitch, Morris (1992). "Dissociation between mental imagery and object recognition in a brain-damaged patient". Nature. 359 (6396): 636–637. Bibcode:1992Natur.359..636B. doi:10.1038/359636a0. PMID 1406994. S2CID 4241164.

- ^ Schlegel, A., Kohler, P. J., Fogelson, S. V, Alexander, P., Konuthula, D., & Tse, P. U. “Network structure and dynamics of the mental workspace”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(40), 16277 LP-16282. (2013).

- ^ Kolb, B., & Whishaw, I. Q. (2015). Fundamentals of Human Neuropsychology. New York. Worth Publishers.

- ^ Ishai, A. “Seeing faces and objects with the "mind's eye”", Archives Italiennes de Biologie, 148(1):1–9. (2010).

- ^ Patey, Douglas Lane (January 1986). "Johnson's Refutation of Berkeley: Kicking the Stone Again". Journal of the History of Ideas. 47 (1): 139–145. doi:10.2307/2709600. JSTOR 2709600.

- ^ Shepard and Metzler 1971

- ^ Gardner 1987

- ^ Kosslyn 1995; see also 1994

- ^ Parsons 1987; 2003

- ^ Schwoebel et al. 2001

- ^ Kosslyn et al. 2001

- ^ Amorim et al. 2006

- ^ Farah, Martha J. (Sep 30, 1987). "Is visual imagery really visual? Overlooked evidence from neuropsychology". Psychological Review. 95 (3): 307–317. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.95.3.307. PMID 3043530.

- ^ Cichy, Radoslaw M.; Heinzle, Jakob; Haynes, John-Dylan (June 10, 2011). "Imagery and Perception Share Cortical Representations of Content and Location" (PDF). Cerebral Cortex. 22 (2): 372–380. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhr106. PMID 21666128.

- ^ Rohrer 2006

- ^ Marks, 1973

- ^ Rodway, Gillies and Schepman 2006

- ^ Rodway et al. 2006

- ^ Gur and Hilgard 1975

- ^ Cui et al. 2007

- ^ Pascual-Leone et al. 1995

- ^ The Dalai Lama at MIT (2006)

- ^ Mental Imagery Archived 2008-02-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Kaur, Jaskirat; Ghosh, Shampa; Sahani, Asish Kumar; Sinha, Jitendra Kumar (2019-04-15). "Mental imagery training for treatment of central neuropathic pain: a narrative review". Acta Neurologica Belgica. 119 (2): 175–186. doi:10.1007/s13760-019-01139-x. ISSN 0300-9009. PMID 30989503. S2CID 115153320.

- ^ Kaur, Jaskirat; Ghosh, Shampa; Sahani, Asish Kumar; Sinha, Jitendra Kumar (November 2020). "Mental Imagery as a Rehabilitative Therapy for Neuropathic Pain in People With Spinal Cord Injury: A Randomized Controlled Trial". Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair. 34 (11): 1038–1049. doi:10.1177/1545968320962498. ISSN 1552-6844. PMID 33040678. S2CID 222300017.

Further reading[edit]

- Albert, J.-M. ‘’Mental Image and Representation. (French text by Jean-Max Albert and translation by H. Arnold) Paris: Mercier & Associés, 2018. [1]

- Amorim, Michel-Ange, Brice Isableu and Mohammed Jarraya (2006) Embodied Spatial Transformations: “Body Analogy” for the Mental Rotation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General.

- Barsalou, L.W. (1999). "Perceptual Symbol Systems". Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 22 (4): 577–660. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.601.93. doi:10.1017/s0140525x99002149. PMID 11301525. S2CID 351236.

- Bartolomeo, P (2002). "The Relationship Between Visual perception and Visual Mental Imagery: A Reappraisal of the Neuropsychological Evidence". Cortex. 38 (3): 357–378. doi:10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70665-8. PMID 12146661. S2CID 4485950.

- Bennett, M.R. & Hacker, P.M.S. (2003). Philosophical Foundations of Neuroscience. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Bensafi, M.; Porter, J.; Pouliot, S.; Mainland, J.; Johnson, B.; Zelano, C.; Young, N.; Bremner, E.; Aframian, D.; Kahn, R.; Sobel, N. (2003). "Olfactomotor Activity During Imagery Mimics that During Perception". Nature Neuroscience. 6 (11): 1142–1144. doi:10.1038/nn1145. PMID 14566343. S2CID 5915985.

- Block, N (1983). "Mental Pictures and Cognitive Science". Philosophical Review. 92 (4): 499–539. doi:10.2307/2184879. JSTOR 2184879.

- Brant, W. (2013). Mental Imagery and Creativity: Cognition, Observation and Realization. Akademikerverlag. pp. 227. Saarbrücken, Germany. ISBN 978-3-639-46288-3

- Cui, X.; Jeter, C.B.; Yang, D.; Montague, P.R.; Eagleman, D.M. (2007). "Vividness of mental imagery: Individual variability can be measured objectively". Vision Research. 47 (4): 474–478. doi:10.1016/j.visres.2006.11.013. PMC 1839967. PMID 17239915.

- Deutsch, David (1998). The Fabric of Reality. ISBN 978-0-14-014690-5.

- Egan, Kieran (1992). Imagination in Teaching and Learning. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Fichter, C.; Jonas, K. (2008). "Image Effects of Newspapers. How Brand Images Change Consumers' Product Ratings". Zeitschrift für Psychologie. 216 (4): 226–234. doi:10.1027/0044-3409.216.4.226. Archived from the original on 2013-01-03.

- Finke, R.A. (1989). Principles of Mental Imagery. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Garnder, Howard. (1987) The Mind's New Science: A History of the Cognitive Revolution New York: Basic Books.

- Gur, R.C.; Hilgard, E.R. (1975). "Visual imagery and discrimination of differences between altered pictures simultaneously and successively presented". British Journal of Psychology. 66 (3): 341–345. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8295.1975.tb01470.x. PMID 1182401.

- Kosslyn, Stephen M. (1983). Ghosts in the Mind's Machine: Creating and Using Images in the Brain. New York: Norton.

- Kosslyn, Stephen (1994) Image and Brain: The Resolution of the Imagery Debate. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Kosslyn, Stephen M.; Thompson, William L.; Kim, Irene J.; Alpert, Nathaniel M. (1995). "Topographic representations of mental images in primary visual cortex". Nature. 378 (6556): 496–498. Bibcode:1995Natur.378..496K. doi:10.1038/378496a0. PMID 7477406. S2CID 127386.

- Kosslyn, Stephen M.; Thompson, William L.; Wraga, Mary J.; Alpert, Nathaniel M. (2001). "Imagining rotation by endogenous versus exogenous forces: Distinct neural mechanisms". NeuroReport. 12 (11): 2519–2525. doi:10.1097/00001756-200108080-00046. PMID 11496141. S2CID 43067749.

- Logie, R.H.; Pernet, C.R.; Buonocore, A.; Della Sala, S. (2011). "Low and high imagers activate networks differentially in mental rotation". Neuropsychologia. 49 (11): 3071–3077. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.07.011. PMID 21802436. S2CID 7073330.

- Marks, D.F. (1973). "Visual imagery differences in the recall of pictures". British Journal of Psychology. 64 (1): 17–24. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8295.1973.tb01322.x. PMID 4742442.

- Marks, D.F. (1995). "New directions for mental imagery research". Journal of Mental Imagery. 19: 153–167.

- McGabhann. R, Squires. B, 2003, 'Releasing The Beast Within – A path to Mental Toughness', Granite Publishing, Australia.

- McKellar, Peter (1957). Imagination and Thinking. London: Cohen & West.

- Norman, Donald. The Design of Everyday Things. ISBN 978-0-465-06710-7.

- Paivio, Allan (1986). Mental Representations: A Dual Coding Approach. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Parsons, Lawrence M (1987). "Imagined spatial transformations of one's hands and feet". Cognitive Psychology. 19 (2): 178–241. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(87)90011-9. PMID 3581757. S2CID 38603712.

- Parsons, Lawrence M (2003). "Superior parietal cortices and varieties of mental rotation". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 7 (12): 515–551. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2003.10.002. PMID 14643362. S2CID 18955586.

- Pascual-Leone, Alvaro, Nguyet Dang, Leonardo G. Cohen, Joaquim P. Brasil-Neto, Angel Cammarota, and Mark Hallett (1995). Modulation of Muscle Responses Evoked by Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation During the Acquisition of New Fine Motor Skills. Journal of Neuroscience [2]

- Plato (2000). The Republic (New CUP translation into English). ISBN 978-0-521-48443-5.

- Plato (2003). Respublica (New CUP edition of Greek text). ISBN 978-0-19-924849-0.

- Prinz, J.J. (2002). Furnishing the Mind: Concepts and their Perceptual Basis. Boston, MA: MIT Press.

- Pylyshyn, Zenon W (1973). "What the mind's eye tells the mind's brain: a critique of mental imagery". Psychological Bulletin. 80: 1–24. doi:10.1037/h0034650.

- Reisberg, Daniel (Ed.) (1992). Auditory Imagery. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Richardson, A. (1969). Mental Imagery. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Rodway, P.; Gillies, K.; Schepman, A. (2006). "Vivid imagers are better at detecting salient changes". Journal of Individual Differences. 27 (4): 218–228. doi:10.1027/1614-0001.27.4.218.

- Rohrer, T. (2006). The Body in Space: Dimensions of embodiment The Body in Space: Embodiment, Experientialism and Linguistic Conceptualization. In Body, Language and Mind, vol. 2. Zlatev, Jordan; Ziemke, Tom; Frank, Roz; Dirven, René (eds.). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Ryle, G. (1949). The Concept of Mind. London: Hutchinson.

- Sartre, J.-P. (1940). The Psychology of Imagination. (Translated from the French by B. Frechtman, New York: Philosophical Library, 1948.)

- Schwoebel, John; Friedman, Robert; Duda, Nanci; Coslett, H. Branch (2001). "Pain and the body schema evidence for peripheral effects on mental representations of movement". Brain. 124 (10): 2098–2104. doi:10.1093/brain/124.10.2098. PMID 11571225.

- Skinner, B.F. (1974). About Behaviorism. New York: Knopf.

- Shepard, Roger N.; Metzler, Jacqueline (1971). "Mental rotation of three-dimensional objects". Science. 171 (3972): 701–703. Bibcode:1971Sci...171..701S. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.610.4345. doi:10.1126/science.171.3972.701. PMID 5540314. S2CID 16357397.

- Thomas, Nigel J.T. (1999). "Are Theories of Imagery Theories of Imagination? An Active Perception Approach to Conscious Mental Content". Cognitive Science. 23 (2): 207–245. doi:10.1207/s15516709cog2302_3.

- Thomas, N.J.T. (2003). Mental Imagery, Philosophical Issues About. In L. Nadel (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science (Volume 2, pp. 1147–1153). London: Nature Publishing/Macmillan.

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to Mental image. |

イメージ

出典は列挙するだけでなく、脚注などを用いてどの記述の情報源であるかを明記してください。 |

イメージまたは心的イメージ、心象、形象、印象とは、「心象」・「印象」・「形象」・「着想」・「想像」・「一般的印象」・「意味合い」・「感覚」・「感じ」等の言葉に置き換えられる。心に思い浮かべる像や情景。ある物事についていだく全体的な感じ。また、心の中に思い描くことを言う。また、何かの物体、出来事、または情景などを知覚する経験に極めて似通った経験であるが、対象となるはずの当の物体、出来事、また情景が感覚において現前していないような経験を言う(McKellar, 1957年、Richardson, 1969年、Finke, 1989年、Thomas, 2003年)。このような経験の本質や、何がこのような経験を可能としているのか、また、この経験に機能が存在する場合、それらは何なのかは、長年にわたり、哲学、心理学、認知科学、更に近年は神経科学における研究と議論の主題であった。

イメージとは何か[編集]

現代の研究者たちがこのような経験について、イメージは知覚のどのモードでも起こり得るとしているため、人は、聴覚イメージ(Reisberg, 1992年)、嗅覚イメージ(Bensafi et al., 2003年)、その他の諸イメージを経験することが可能となる。とはいえ、この問題についての哲学的及び科学的研究のほとんど大部分は、「視覚」イメージを中心の主題としている。人類と同様に、多様な種類の動物たちがまた、心的イメージを経験する能力を有すると広く推定されている。しかし、この現象の根本的に主観的な性質からして、この推定を支持する証拠も、反駁する証拠も、見出すことはできない。

バークレー、そしてヒュームのような哲学者や、ヴント及びジェイムズのような初期の経験主義心理学者は、一般に観念(ideas)が心的イメージであると考えていた。今日にあっては、イメージは心的表象として働き、記憶と思考において重要な役割を果たしていると広く信じられている(Allan Paivio, 1986年、Kieran Egan, 1992年、Lawrence W. Barsalou, 1999年、Prinz, 2002年)。

実際、ある研究者は、イメージとは「定義からして」内的で、心的またはニューラルな表象(representation)の形式として理解するのが最も妥当だと示唆するまでに至っている(Ned Block, 1983年; Stephen Kosslyn, 1983年)。とはいえ、別の研究者は、イメージの知覚経験とは、心または大脳におけるこのような表象といかなる意味でも同等ではないし、このような表象から直接に導かれる訳でもないと主張している(サルトル, 1940年、ギルバート・ライル, 1949年、スキナー, 1974年、Thomas, 1999年、Bartolomeo, 2002年、Bennett & Hacker, 2003年)。

イメージは大脳内で何を構成するか[編集]

我々は、読書をしているとき、何かの出来事について心的なイメージが把握できたように感じるのは何ゆえなのか、不思議に思うことがある。また白昼夢を見ていた場合にも疑問は起こる。このような経験で得られる心的イメージは、あたかも頭のなかに絵があるように見える。例えば、音楽家が歌を聞く場合、時として頭のなかで歌の「音符」が見えることがある。これは残像(after-image)とは異なっている。例えば、何かの出来事から誘導された残像は、意識的なコントロールの許にはないと考えられている。しかし、他方、想像において、あるいは心のなかでイメージを想起する場合、イメージは意志の自由になると考えられる。それ故、イメージまたは心像というものは、様々な意識的コントロールの度合いを持つものとして特徴付けられる。

ある生物学者たち[誰?]によれば、我々は環境世界についての経験を、心的イメージとして蓄積しており、心的イメージは他の心的イメージと連合されたり比較され、こうしてまったく新しいイメージが合成されるのだとされる。例えば、夢を見たり、想像力を働かす場合に、このようなことが起こる。この理論は、このような過程によって、我々は、世界がどのように働くかに関する有用な理論を、心的イメージの適切な連続に基づいて構成することが可能になり、この機構は、推論・演繹あるいはシミュレーションの過程を通じて得られる結果などを直接に経験しなくとも成り立つと主張する。人間以外の生物が、このような能力を持っているかどうかは議論されている(「動物の認識」を参照)。

心的イメージについての哲学の解釈[編集]

心的イメージは、知識の研究にとって要の問題であるため、今も昔も哲学において重要な主題である。『国家』第7巻において、プラトンは、洞窟のなかの囚人のメタファー(暗喩)を使用している。囚人は束縛され身動きできない状態で、光源である火を背にして座り、彼の前にある壁を見ている。彼らは、人々が彼の背後で運んでくる色々な物体が投影された影を見るのである。人々が運んでくる物体とは、世界のなかに存在する真なる事物のことである。囚人は、経験によって得られたセンスデータを元に心的イメージを造り出す人間に似ている、とソクラテスは説明する。

もっと後では、バークレー司教が、その観念論の理論において、似たような考えを主張している。バークレーは、実在は心的イメージ(心の表象)と等価である-我々が抱く心的イメージは、別の物質的実在(material reality)の複写ではなく、実在それ自体であると述べた。とはいえ、バークレーは、彼が外的世界を構成すると見なすイメージと、個人の想像力が生み出すイメージを明瞭に区別した。バークレーに従うと、後者のみが、今日における用語法の意味での「心的イメージ(心像)」と見なされる。

18世紀の英国の文筆家であるサミュエル・ジョンソン博士は、観念論を批判している。スコットランドで屋外を散歩していたとき、観念論の是非について問われた彼は、断言して次のように答えた。「かくのごとく、そんなものは否定する」ジョンソンは傍らの大きな岩を脚で蹴り、脚が跳ね返るのを示しつつ、かく述べた。彼の主張のポイントは、岩が心的イメージであって、それ自身の物質的実在を有しないとする概念(concept)、考え(thought)、アイデア(idea)は、彼がまさに岩を蹴ることで経験した痛みのセンスデータの説明としては妥当ではないと云うことである。

参考文献[編集]

- Amorim, Michel-Ange, Brice Isableu and Mohammed Jarraya (2006) Embodied Spatial Transformations: “Body Analogy” for the Mental Rotation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General.

- Barsalou, L.W. (1999). Perceptual Symbol Systems. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 22: 577 - 660.

- Bartolomeo, P. (2002). The Relationship Between Visual perception and Visual Mental Imagery: A Reappraisal of the Neuropsychological Evidence. Cortex 38: 357 - 378. Cortex open access archive

- Bennett, M.R. & Hacker, P.M.S. (2003). Philosophical Foundations of Neuroscience. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Bensafi, M., Porter, J., Pouliot, S., Mainland, J., Johnson, B., Zelano, C., Young, N., Bremner, E., Aframian, D., Kahn, R., & Sobel, N. (2003). Olfactomotor Activity During Imagery Mimics that During Perception. Nature Neuroscience 6: 1142 - 1144.

- Block, N. (1983). Mental Pictures and Cognitive Science. Philosophical Review 92: 499 - 539.

- Cui, X., Jeter, C.B., Yang, D., Montague, P.R.,& Eagleman, D.M. (2007). "Vividness of mental imagery: Individual variability can be measured objectively". Vision Research, 47, 474 - 478.

- Deutsch, David. The Fabric of Reality. ISBN 0-14-014690-3

- Egan, Kieran (1992). Imagination in Teaching and Learning. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Finke, R.A. (1989). Principles of Mental Imagery. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Garnder, Howard. (1987) The Mind's New Science: A History of the Cognitive Revolution New York: Basic Books.

- Gur, R.C. & Hilgard, E.R. (1975). "Visual imagery and discrimination of differences between altered pictures simultaneously and successively presented". British Journal of Psychology, 66, 341 - 345.

- Kosslyn, Stephen M. (1983). Ghosts in the Mind's Machine: Creating and Using Images in the Brain. New York: Norton.

- Kosslyn, Stephen (1994) Image and Brain: The Resolution of the Imagery Debate. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Kosslyn, Stephen M., William L. Thompson, Irene J. Kim and Nathaniel M. Alpert (1995) Topographic representations of mental images in primary visual cortex. Nature 378: 496 - 498.

- Kosslyn, Stephen M., William L. Thompson, Mary J. Wraga and Nathaniel M. Alpert (2001) Imagining rotation by endogenous versus exogenous forces: Distinct neural mechanisms. NeuroReport 12, 2519 - 2525

- Marks, D.F. (1973). "Visual imagery differences in the recall of pictures". British Journal of Psychology, 64, 17 - 24.

- Marks, D.F. (1995). "New directions for mental imagery research". Journal of Mental Imagery, 19, 153 - 167.

- McGabhann. R, Squires. B, 2003, 'Releasing The Beast Within — A path to Mental Toughness', Granite Publishing, Australia.

- McKellar, Peter (1957). Imagination and Thinking. London: Cohen & West.

- Norman, Donald. The Design of Everyday Things. ISBN 0-465-06710-7

- Paivio, Allan (1986). Mental Representations: A Dual Coding Approach. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Parsons, Lawrence M. (1987) Imagined spatial transformations of one’s hands and feet. Cognitive Psychology 19: 178 - 241.

- Parsons, Lawrence M. (2003) Superior parietal cortices and varieties of mental rotation. Trends in Cognitive Science 7: 515 - 551.

- Pascual-Leone, Alvaro, Nguyet Dang, Leonardo G. Cohen, Joaquim P. Brasil-Neto, Angel Cammarota, and Mark Hallett (1995). Modulation of Muscle Responses Evoked by Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation During the Acquisition of New Fine Motor Skills. Journal of Neuroscience [1]

- Plato. The Republic (New CUP translation into English). ISBN 0-521-48443-X

- Plato. Respublica (New CUP edition of Greek text). ISBN 0-19-924849-4

- Prinz, J.J. (2002). Furnishing the Mind: Concepts and their Perceptual Basis. Boston, MA: MIT Press.

- Pylyshyn, Zenon W. (1973). What the mind’s eye tells the mind’s brain: a critique of mental imagery. Psychological Bulletin 80: 1 - 24

- Reisberg, Daniel (Ed.) (1992). Auditory Imagery. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Richardson, A. (1969). Mental Imagery. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Rodway, P., Gillies, K. & Schepman, A. (2006). "Vivid imagers are better at detecting salient changes". Journal of Individual Differences 27: 218 - 228.

- Rohrer, T. (2006). The Body in Space: Dimensions of embodiment The Body in Space: Embodiment, Experientialism and Linguistic Conceptualization]. In Body, Language and Mind, vol. 2. Zlatev, Jordan; Ziemke, Tom; Frank, Roz; Dirven, René (eds.). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, forthcoming 2006.

- Ryle, G. (1949). The Concept of Mind. London: Hutchinson.

- Sartre, J.-P. (1940). The Psychology of Imagination. (Translated from the French by B. Frechtman, New York: Philosophical Library, 1948.)

- Schwoebel, John, Robert Friedman, Nanci Duda and H. Branch Coslett (2001). Pain and the body schema evidence for peripheral effects on mental representations of movement. Brain 124: 2098 - 2104.

- Skinner, B.F. (1974). About Behaviorism. New York: Knopf.

- Shepard, Roger N. and Jacqueline Metzler (1971) Mental rotation of three-dimensional objects. Science 171: 701 - 703.

- Thomas, Nigel J.T. (1999). Are Theories of Imagery Theories of Imagination? An Active Perception Approach to Conscious Mental Content. Cognitive Science 23: 207 - 245.

- Thomas, N.J.T. (2003). Mental Imagery, Philosophical Issues About. In L. Nadel (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science (Volume 2, pp. 1147 - 1153). London: Nature Publishing/Macmillan.

関連項目[編集]

外部リンク[編集]

- Imagination, Mental Imagery, Consciousness, and Cognition: Scientific, Philosophical and Historical Approaches.

- Roadmind University The Roerich Psychodynamic Inventory (RPI) provides statisical data to determine the validity of mental imagery for cognition of the minds raw emotional state. (Dr. Robert Roerich MD.)

- Mental Imagery in Mathematics

- インクィジティブ・マインド:Mental Imagery (メンタルイメージ:心的イメージ)

- text copy/ en:Mental image 20:29, 28 August 2007 より text copy et 部分翻訳

- contributors/ Thruston, GregA, Antonrojo, TheConstantGardner, Treharne et al.

이미지

출처 는 열거할 뿐만 아니라 각주 등을 이용하여 어느 기술의 출처인지를 명기 해 주십시오. |

이미지 또는 심적 이미지, 심상, 형상, 인상 이란, 「심상」・「인상」・「형상」・「착상」・「상상」・「일반적인 인상」・「의미 」・「감각」・「 느낌 등의 단어 로 대체된다. 마음에 떠오르는 동상 이나 정경. 어떤 것에 대해 받는 전반적인 느낌. 또, 마음속에 생각 그리는 것을 말한다. 또, 무언가의 물체 , 사건 , 또는 정경 등을 지각 하는 경험에 극히 닮은 경험 이지만, 대상이 될 당의 물체, 사건, 또 정경이 감각 에 있어서 현전하고 있지 않은 것 같은 경험을 말한다 (McKellar, 1957년, Richardson, 1969년, Finke, 1989년, Thomas, 2003년). 이러한 경험 의 본질이나, 무엇이 그러한 경험을 가능하게 하고 있는지, 또, 이 경험에 기능 이 존재 하는 경우, 그들은 무엇인가는, 수년에 걸쳐, 철학 , 심리학 , 인지 과학 , 더욱 최근에는 신경과학연구 와 토론 의 주제 였다 .

이미지란 무엇인가 [ 편집 ]

현대 연구자들이 이러한 경험에 대해 이미지는 지각의 어떤 모드에서도 발생할 수 있기 때문에 사람은 청각 이미지 (Reisberg, 1992), 후각 이미지 (Bensafi et al., 2003) 등 의 여러 이미지를 경험하는 것이 가능해진다. 그럼에도 불구하고이 문제에 대한 철학적 및 과학적 연구 의 대부분은 "시각"이미지를 중심의 주제로하고 있습니다. 인류와 마찬가지로 다양한 종류의 동물들이 심적 이미지를 경험할 수있는 능력을 가진 것으로 널리 추정됩니다. 그러나, 이 현상의 근본적으로 주관적인 성질로부터, 이 추정을 지지하는 증거도, 반박하는 증거도, 발견할 수 없다.

버클리 와 퓸 과 같은 철학자와 벤트 와 제임스 와 같은 초기 경험주의 심리학자 들은 일반적으로 아이디어 가 심적 이미지라고 생각했다. 오늘날 이미지는 심적 표상 으로 작용하고 기억 과 사고 에서 중요한 역할 을 한다고 널리 믿어지고 있다(Allan Paivio, 1986, Kieran Egan, 1992, Lawrence W. Barsalou, 1999). , Prinz, 2002년).

사실, 한 연구자는 이미지와는 "정의에서"내적이고, 심적 또는 신경 적인 표현의 형태로 이해 하는 것이 가장 타당하다고 시사 하기까지 이르고 있다 (Ned Block, 1983; Stephen Kosslyn, 1983). 그럼에도 불구하고, 다른 연구자들은 이미지의 지각 경험이 마음 이나 대뇌 의 이러한 표상과 어떠한 의미 에서도 동등하지 않고, 그러한 표상에서 직접 이끌어 낼 수 없다고 주장한다. ( 사르틀 , 1940년, 길버트 라일 , 1949년, 스키너 , 1974년, Thomas, 1999년, Bartolomeo, 2002년, Bennett & Hacker, 2003년).

이미지는 대뇌 내에서 무엇을 구성하는지 [ 편집 ]

우리는 독서 를 할 때 무언가의 사건에 대해 심적인 이미지를 파악할 수 있었던 것처럼 느끼는 것은 무엇 때문인지, 이상하게 생각할 수 있다. 또 백일몽 을 보았을 경우에도 의문 은 일어난다. 이러한 경험으로 얻을 수 있는 심적 이미지는 마치 머리 속에 그림 이 있는 것처럼 보인다. 예를 들어, 음악가 가 노래 를 듣는 경우, 때로는 머리 속에서 노래의 ' 음표 '가 보일 수 있다. 이것은 잔상 (after-image)과 다르다. 예를 들어, 어떤 사건에서 유래된 잔상은 의식 적인 통제 의 용서에 없는 것으로 여겨진다. 그러나 다른 한편, 상상 에서, 또는 마음 속에서 이미지를 상기시키는 경우, 이미지는 의지의 자유 가 된다고 생각된다. 따라서 이미지 또는 심상이라는 것은 다양한 의식적 컨트롤 정도를 갖는 것으로 특징 지어 집니다.

한 생물 학자 들 [ 누구 ? _ _ _ _ _ 가 합성된다고 한다. 예를 들어, 꿈 을 꾸거나 상상력 을 일하는 경우에 이런 일이 일어난다. 이 이론 은 이러한 과정을 통해 우리는 세상이 어떻게 작동하는지에 관한 유용한 이론을 심적 이미지의 적절한 연속에 기초하여 구성할 수 있게 된다 . 연역 혹은 시뮬레이션 과정을 통해 얻을 수 있는 결과 등을 직접 경험하지 않아도 성립한다고 주장한다. 인간 이외의 생물 이 이러한 능력 을 가지고 있는지 여부는 논의 되고 있다( 동물의 인식 참조).

심적 이미지에 대한 철학 해석 [ 편집 ]

심적 이미지는 지식 연구에 중요한 문제 이기 때문에 지금도 옛날에도 철학 에서 중요한 주제 이다. 『국가』 제7권에 있어서, 플라톤 은, 동굴 의 죄수 의 메타파( 암유 )를 사용하고 있다. 죄수는 속박 되어 움직일 수 없는 상태에서 광원 인 불 을 등에 앉고 그의 앞에 있는 벽 을 보고 있다. 그들은 사람들이 그의 뒤에서 운반하는 다양한 물체 가 투영 된 그림자를 보기 때문이다. 사람들이 운반하는 물체란 세계 속에 존재하는 참된 사물이다. 죄수는 경험에 의해 얻은 센스 데이터 를 바탕으로 심적 이미지를 만들어내는 인간과 비슷하다고 소크라테스 는 설명한다.

나중에 버클리 주교 는 그 관념론 의 이론에서 비슷한 생각을 주장 했다. 버클리는 실재는 심적 이미지(마음의 표상)와 동등 하다 . 하지만 버클리는 그가 외적 세계를 구성한다고 생각하는 이미지와 개인 의 상상력이 만들어내는 이미지를 명료하게 구별했다. 버클리에 따르면, 후자만이 오늘날의 용어 법의 의미에서 "심적 이미지 (심상)"로 간주됩니다.

18세기 영국 의 문필가인 사무엘 존슨 박사 는 관념론을 비판하고 있다. 스코틀랜드 에서 옥외를 산책 했을 때, 관념론의 부디에 대해 물었던 그는 , 단언하고 다음과 같이 대답했다. "그렇듯이, 그런 것은 부정한다" 존슨은 옆의 큰 바위를 다리 로 걷어차 다리가 튀어 나오는 것을 보여주면서 말했다. 그의 주장의 포인트는, 바위 가 심적 이미지이며, 자신의 물질적 실재를 갖지 않는다고 하는 개념 (concept), 생각 (thought), 아이디어 (idea)는, 그가 바로 바위를 걷어차는 것 에서 경험한 통증의 센스 데이터의 설명으로서는 타당하지 않다고 말하는 것이다.

참고 문헌 [ 편집 ]

- Amorim, Michel-Ange, Brice Isableu 및 Mohammed Jarraya(2006) 구현된 공간 변환: 정신 회전에 대한 "신체 유추". 실험 심리학 저널: 일반.

- Barsalou, LW (1999). 지각 기호 시스템. 행동 및 뇌 과학 22: 577 - 660.

- Bartolomeo, P. (2002). 시각적 인식과 시각적 정신적 심상 사이의 관계: 신경심리학적 증거의 재평가. Cortex 38: 357 - 378. Cortex 오픈 액세스 아카이브

- Bennett, MR & Hacker, PMS(2003). 신경과학의 철학적 기초. 옥스포드: 블랙웰.

- Bensafi, M., Porter, J., Pouliot, S., Mainland, J., Johnson, B., Zelano, C., Young, N., Bremner, E., Aframian, D., Kahn, R., & Sobel, N. (2003). 심상 중 후각 운동 활동은 지각 중 이를 모방합니다. 자연 신경 과학 6: 1142 - 1144.

- 블록, N. (1983). 정신 그림과 인지 과학. 철학적 검토 92: 499 - 539.

- Cui, X., Jeter, CB, Yang, D., Montague, PR, & Eagleman, DM(2007). "심상 이미지의 선명도: 개인의 다양성을 객관적으로 측정할 수 있습니다." 비전 연구, 47, 474 - 478.

- 도이치, 데이빗. 현실의 직물 . ISBN 0-14-014690-3

- 이건, 키어런(1992). 가르침과 배움의 상상력 . 시카고: University of Chicago Press.

- Finke, RA(1989). 정신 이미지의 원리. 캠브리지, MA: MIT Press.

- 가더, 하워드. (1987) 마음의 새로운 과학: 인지 혁명의 역사 뉴욕: 기초 서적.

- Gur, RC & Hilgard, ER (1975). "동시에 그리고 연속적으로 제시되는 변경된 그림 사이의 시각적 이미지와 차이점 구별". 영국 심리학 저널, 66, 341 - 345.

- Kosslyn, Stephen M. (1983). 마음의 기계에 있는 유령: 뇌에서 이미지 생성 및 사용. 뉴욕: 노턴.

- Kosslyn, Stephen (1994) 이미지와 두뇌: 이미지 논쟁의 해결. 캠브리지, MA: MIT Press.

- Kosslyn, Stephen M., William L. Thompson, Irene J. Kim 및 Nathaniel M. Alpert(1995) 1차 시각 피질에서 정신적 이미지의 지형적 표현. 자연 378: 496 - 498.

- Kosslyn, Stephen M., William L. Thompson, Mary J. Wraga 및 Nathaniel M. Alpert (2001) 내인성 대 외인력에 의한 회전 상상: 뚜렷한 신경 메커니즘. NeuroReport 12, 2519 - 2525

- 막스, DF(1973). "그림의 회상에서 시각적 이미지의 차이". 영국 심리학 저널, 64, 17 - 24.

- 막스, DF(1995). "심상 심상 연구를 위한 새로운 방향". 정신 이미지 저널, 19, 153 - 167.

- 맥개반. R, 스콰이어즈. B, 2003, '내 안의 야수 풀기 - 정신적 강인함으로 가는 길', Granite Publishing, 호주.

- 맥켈러, 피터(1957). 상상력과 생각. 런던: 코헨 & 웨스트.

- 노먼, 도널드. 일상적인 것의 디자인 . ISBN 0-465-06710-7

- 파이비오, 앨런(1986). 정신 표현: 이중 코딩 접근 방식. 뉴욕: 옥스포드 대학 출판부.

- Parsons, Lawrence M. (1987) 손과 발의 공간적 변형을 상상했습니다. 인지 심리학 19: 178 - 241.

- Parsons, Lawrence M. (2003) 우수한 정수리 피질 및 정신 회전의 다양성. 인지 과학의 동향 7: 515 - 551.

- Pascual-Leone, Alvaro, Nguyet Dang, Leonardo G. Cohen, Joaquim P. Brasil-Neto, Angel Cammarota 및 Mark Hallett(1995). 새로운 미세 운동 기술을 습득하는 동안 경두개 자기 자극에 의해 유발되는 근육 반응의 조절. 신경과학 저널 [1]

- 플라톤. Republic(새 CUP 영어 번역) . ISBN 0-521-48443-X

- 플라톤. Respublica(그리스어 텍스트의 새로운 CUP 판 ) ISBN 0-19-924849-4

- Prinz, JJ (2002). 마음의 공급: 개념과 그 지각적 기초. 매사추세츠주 보스턴: MIT Press.

- Pylyshyn, Zenon W. (1973). 마음의 눈이 마음의 뇌에게 말하는 것: 정신적 이미지에 대한 비판. 심리 게시판 80: 1 - 24

- Reisberg, Daniel (Ed.) (1992). 청각적 이미지. 힐스데일, 뉴저지: 얼바움.

- Richardson, A. (1969). 정신 이미지. 런던: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Rodway, P., Gillies, K. & Schepman, A. (2006). "생생한 이미저는 현저한 변화를 감지하는 데 더 좋습니다." 개인차 저널 27: 218 - 228.

- Rohrer, T. (2006). 공간 속의 몸: 체현의 차원 공간 속의 몸: 체현, 경험주의와 언어적 개념화]. 몸, 언어 및 마음, vol . 2. 즐라테프, 요르단; 지엠케, 톰; 프랭크, 로즈; Dirven, René (ed.). 베를린: Mouton de Gruyter, 2006년 출시 예정.

- Ryle, G. (1949). 마음의 개념. 런던: 허친슨.

- 사르트르, J.-P. (1940). 상상의 심리학. (뉴욕의 B. Frechtman이 프랑스어에서 번역: Philosophical Library, 1948.)

- Schwoebel, John, Robert Friedman, Nanci Duda 및 H. Branch Coslett(2001). 움직임의 정신적 표현에 대한 주변 효과에 대한 통증 및 신체 도식 증거. 두뇌 124: 2098 - 2104.

- 스키너, BF(1974). 행동주의에 대하여. 뉴욕: 크노프.

- Shepard, Roger N. 및 Jacqueline Metzler(1971) 3차원 물체의 정신적 회전. 과학 171: 701 - 703.

- Thomas, Nigel JT(1999). 심상 이론은 상상 이론인가? 의식적 정신 내용에 대한 능동적 지각 접근. 인지 과학 23: 207 - 245.

- Thomas, NJT(2003). 정신적 이미지, 철학적 문제에 관한. L. Nadel(Ed.), 인지 과학 백과사전 (2권, 1147~1153페이지). 런던: 네이처 퍼블리싱/맥밀런.

관련 항목 [ 편집 ]

외부 링크 [ 편집 ]

- 상상력, 정신적 이미지, 의식 및 인지: 과학적, 철학적 및 역사적 접근.

- Roadmind University Roerich Psychodynamic Inventory(RPI)는 마음의 원시 감정 상태에 대한 인지에 대한 정신 이미지의 유효성을 결정하기 위한 통계 데이터를 제공합니다. (Robert Roerich MD 박사)

- 수학에서의 정신 이미지

- 인퀴지티브 마인드: Mental Imagery (멘탈 이미지: 심적 이미지)

- text copy/ en:Mental image 20:29, 28 August 2007 에서 text copy et 부분 번역

- 기고자/ Thruston , GregA , Antonrojo , TheConstantGardner , Treharne et al.