Showing posts with label 수피즘. Show all posts

Showing posts with label 수피즘. Show all posts

2022/07/28

現代の「イラン的イスラム」哲学におけるコ ルバンと井筒の役割に関する導入的比較研 究:ハイデガーからマシニョンまで エフサン・シャリーアティー 翻訳:景山 洋平

国際哲学別冊7.indd

現代の「イラン的イスラム」哲学におけるコ

ルバンと井筒の役割に関する導入的比較研

究:ハイデガーからマシニョンまで

エフサン・シャリーアティー

翻訳:景山 洋平

===

現代の「イラン的イスラム」哲学におけるコルバンと井筒の役割に関する導入的比較研究:ハイデガーからマシニョンまで

エフサン・シャリーアティー翻訳:景山 洋平

アンリ・コルバンは、真剣な検討を改めて受けてしかるべき現代世界の精神的な哲学者たちのなかでも、特に、(大陸ヨーロッパにおける)現代西洋哲学と(イランとイスラム世界、特にシーア派における)東洋哲学との架橋に仕える現象学的=解釈学的な系譜との比較哲学1(と神秘主義)の領域に位置づけられる。一方では、このフランスの哲学者はドイツの哲学的言語のエキスパートであり、マルティン・ハイデガーの二つの作品をはじめてフランス語に翻訳した人物である。ただし、その一方で、同時に、中世の傑出した歴史家のエティエンヌ・ジルソンの弟子として、そして、プロテスタント神学者であるジャン・バルージの弟子として、そして、最終的に、(1928 年以後は)ルイ・マシニョンの指導のもとに、コルバンは、イスラム世界とシーア派における精神哲学、神秘主義、そしてスーフィズムへと転換した。初めてイブン・アラービーに熱中した後、コルバンはシャブン・アル=ディン=スフラワルディ(1191 年没)とそのヒクマート・アル=イシュラク(曙の神智学あるいは東洋の神智学)の再読にことさらに取り組んだ。その後、彼は、ミルダマードや、ムラ・サドラと彼のヒクマート・モターリアー(至高の神智学)といった、他のそれほど知られていないイランの神智学者を、体系的な仕方で世界に紹介する仕事を始めた。自らが被った「西洋における追放」から逃れつつ、コルバンは東洋(ソフラワルディが意図した意味で)を探究し、それを、パルシア(またはイラン)の中心にして標準を定める地の内に、ある種の「観念」(イメージ)として見いだした。コルバンのイラン来訪とその著作は、イスラム文化の内で育てられたイランの哲学的な知識人世代に影響を与えたが、それは特に、彼ら ― アフマド・ファルディッド、ダルユシュ・シャイェガン、レザ・ダーワリといった人びと ― に自らを認識させる事を通じてその自信を増大させたからなのだ。彼は、世界中で、共通したパースペクティブを持つ他の人びとにも影響を与えた。フランスで、彼はイランにおけるイスラム哲学と神秘主義の伝統を紹介し、そして、彼の作品はクリスチャン・ジャンベのような新世代の哲学者まで惹き付けた。日本とそして世界的に見ても傑出した哲学上の人物でありまたイスラム学者でもあった井筒俊彦は、明らかにコルバンの影響の下に、比較哲学研究に転向し、イブン・アラービーの知的遺産と道教の教説を比較する作業をおこなった。イランとイスラム世界に関する彼の研究の集成は、今日でも真剣な注意を向けられる(そして今なお批判と研究を受ける)主題である。

コルバンがハイデガーから学んだ重要(*** )な教訓は、現存在の実存が自ら自身に関する現存在の生き生きと歩み抜かれる了解(解釈)によって形成されることである。ハイデガーが『日本の友人との対話(言語についての対話)』2で自らの過去の知的成長について指摘するように、ハイデガーは長きに渡り、若い時分の初期の神学研究を通して、ディルタイによる「解釈学」概念の理解に親しんできた。ハイデガーの目的は、ロゴスにおける啓示が可能となる領域を打ち開くことである3。だが、ハイデガーと違い、コルバンは、この解釈学の鍵ないし解釈の方法を、実=存と地平的超越に則して有限性へと深く方向づけられたフライブルクの巨匠の世界観とは異なる他の目的に用いる。則ち、コルバンは、この解釈学の鍵を、「観念」の世界として知られるある他の世界(「観念」の世界、「どこにもない領野、マラクート、ホルクエリアあるいはスフラワルディの『第八の風土』」4)を開くのに使用したのだが、この世界は必ずしも死に方向づけられたものでなく、むしろ、死とは反対側ないし「その彼方に」あるものである。コルバンの見解では、ナスット(自然あるいは経験的与件の感覚知覚)とジャバルート(理性の世界ないし天界の純粋な理性の諸範疇)の領域の中間に位置づけられたマラクートの領域(天使の世界)は、人間の魂ないし「プシュケー」が持つ架橋的な圏域である。つまり、それは、二種の運動によって他の二つの圏域を結合する「能動的想像力」の領野である。ハイデガーの解き明かしえぬ問いに、その方法論的には解釈学的な道行きにおいて応答すると、コルバンの現象学は「霊的解釈」ないし公教的なものの秘教的なものへの差し向けに依拠するもの、つまり、(ハイデガーの被暴露性と同じく)隠されたものの露呈、そして、シーア派の神智学者による「覆いを取り去られたもの」5(カシュフ・アル=マージュブ、ア‒レーテイア)としての真理観に依拠している。

(アンリ・ベルクソンと彼の持続ないしデュレの理論の後では)ハイデガー思想の魅力は ― 彼の思想と「言語」に加えて ― 「時間」に関して彼が新しい概念を提示したことによるものである。ハイデガーは、時間を、将来から生成する統一された全体として描出すると同時に(、将来に仕えるところの)過去の伝統の取り戻しの方途としても描き出したのだが、これは極めて革新的なものであった。ハイデガーの言葉でいうと歴史的時代の進展はいかなる必然的な論理的で先行的に構造化された進歩の系列ももつものでないのだが、これは、ヘーゲルによる単線的な進歩の観念とは全く反対のものである。明らかに、こうした時間と歴史の概念は、ある側面ではイスラム的な時間概念の理解に類似している。マシニョンはクルアーンの「時間と空間」の概念を

「瞬間」と「点」の銀河系(milky way)として記述したものである6。

ヘーゲルの歴史哲学に対するハイデガーの批判に影響を受けつつ、コルバ

ンは、「歴史学的(historique)」の語とは異なる古いフランス語の単語「歴史的 (historial)」を蘇らせ、そうすることで、「経験的な意味で歴史的」(存在者的概念)と「運命としての歴史」ないしは《生起として歴史的(geschichtlich)》(存在論的概念)を区別しようとした。彼は、ハイデガー哲学における歴史性と地平的超越の領域を、垂直に上昇する霊的にして神聖な「形而上学」の一種へと転化させた(とはいえ、それはハイデガーが否定的な意味で考えた「形而上学」としてではない)。

近代的主観性に対するハイデガーの根本的批判は、芸術(詩作)への期待に尊厳を回復してその再生に道を開く。その際、詩作は、伝統を回復し、更には聖なるものの帰還を準備するという目的に、そして、将来せる神の到来のための基盤を準備することとしての瞑想的思索にも仕えるのである。この思索の隠れた源泉は、キリスト教神秘主義(エックハルトなど)に由来するよりむしろ、道教的伝統を戴く東洋の叡智のテキストとその翻訳を徹底して読み抜いたことにより深い根を持つものである7。とはいえ、神学者 ― 特にキルケゴール的な傾向を持った神学者 ― との真剣な対話への彼の信念にもかかわらず、そして、カール・バルト(1968 年没)のような人物の思想を熟知して、ルドルフ・ブルトマンのような人物の思想にハイデガー自身が影響を与えたにもかかわらず、彼は自らの作品が「神学的」に読まれることを許容しなかったし(例えば、ジルソンが企てた新トマス主義的なアプローチによってキリスト教哲学を構築する試み)、そうした企てを、彼が方法論的に無神論的と見なした哲学の徹底した問いの営為と両立しないものと考えた。彼のなかば神秘主義的な傾向、あるいは、特に芸術と詩作の領野における「聖なるもの(heilige)」への着目は、「宗教的」ないし「神学的」神秘主義と性格づけられるものではない(たとえ他方で、サルトルの著作がそうでありうるような意味では、彼の思想が非神学的ないし無神論的とは性格づけられえないにせよ)。この分野でいうとウィトゲンシュタインと似た仕方で、ハイデガーは、「語りえぬものについては沈黙しなければならない」と信じていたように思われる。しかるに、たとえ哲学の営為の方法論に限定されるとしても、こうしたタイプの不可知論的懐疑主義がコルバンの霊的な渇きを癒せない事は明白である。中世のイスラム教とキリスト教の哲学史に関するジルソンの知識から学ぶことによって、コルバンはマシニョンのような人物の情熱に影響を受けたのだ。そして、そのマシニョンは、生ける神性に向かうハラージュの叡智の変容する道のりに、実存的な仕方で、また生きられた経験において、随従したのであるが、その一方で、心根の底から感得する思索の方法を追ってサルマン・パルーシの足跡を辿りもしたのである(クルアーンの用語を使うなら「心情による思索」である)。

マシニョンの思想に拠り所を求めることにより、コルバンは、イラン的イスラムの秘教主義ないし霊性と神秘主義(スーフィズム)への包括的なアプローチを採用した(論考「サルマン・パルーシー:イラン的イスラムの最初の霊的開花 1934 年まで」の表題におけるこの概念を参照せよ)。サルマン・エ・パク(そして、マスダ教からキリスト教を経てイスラムとシーア派に至る彼の霊的発展)は、そうしたアプローチとイランおよびイスラムの霊性と神秘主義を典型的に代表している。

だが、師と弟子の間にはいくつかの点で相違点がある8。

― 第一に、イスラム世界へのマシニョンのアプローチは常に宗教的・神秘的なものと社会的・歴史的なものの二つのアスペクトを合同させるものである。他方で、コルバンは、世界中の他の霊的伝統との対話を打ち立てるためにメタ歴史的な領域を探究していた。こうした違いは、神秘主義と社会的コミットメントの関係に関する二つの異なるタイプをこの両人が抱くことへと繋がった。

― 両者の第二の違いは、イランのシーア派の長所と短所に関する評価と批判への両者の感受性にある。

― 第三の違いは、イブン・アラービーの知的遺産、特に、存在の統一の教説に関する彼らの評価にある。

マシニョンは、初期の直感的な神秘主義と比べて、後期の理論的(ないし存在に定位する)神秘主義が、新プラトン主義哲学9がキリスト教化されたもの(則ち、流出論)と混合されてきたと疑った。この場合、直感的に霊魂に根ざした「情熱」はギリシア的な本性(ロゴス)の範疇的・心理的な思想の一種に変身させられてしまう恐れがあり、そうして、宇宙論から倫理学的哲学・政治学にいたる多様な領野における自然的・知的・批判的な理論的営為に対する懐疑主義と延期のせいで、― ニーチェ的な言葉を使うと ― ギリシア人の自然な喜ばしき(gay)性格から受益することもなくなるのである。

一方で、マシニョンは、存在の統一の教説を、多様の統一という意味での一神教とは技術的に同一視できない、多神教的本性を持った実存的一元論のある形式として記述した。他方で、彼は、神秘主義の領域において知的=理論的アプローチが過剰に用いられることは、― 語のキルケゴール的な意味において ― 宗教的な諸概念から、その悲劇的=逆説的な深さを奪い取ってしまうと信じた。

最後に、マシニョンはスーフィズムの世界からの隠遁と社会からの隔離には馴染むことがなかったが、それだけでなく、彼は、民衆と被造物に対する社会的責任の感覚の内に、聖なるものへの信仰と愛の対応物を見た。だが、彼の哲学的な嗜好と修養過程の結果として、彼は、イブン・アラービーの神秘主義的遺産の理論的な(そしてプラトン的な)アスペクトを、特に、能動的想像力に関する彼の理論的営為を高く評価した。彼は、公教的一神論(アラー以外に神はなし)の反対物として、秘教的一神論(存在の内にはアラー以外に何も無い)を存在の統一と同一のものと考え10、そして、一元論との批判を拒絶した。コルバンは、聖なるものと伝説的歴史を社会学的歴史主義に還元することを避けたし、政治的事象に表だった関心を示すことはなかっ

た。

アブラハムの諸宗教において、「人格化された(道徳的な)神」の概念は、形象的に、人間との対話的関係を設立するための基盤となってきた。イクバル・ラフーリの言葉で言うと、「神の擬人的な概念は、生の理解にとって避けがたいものである… 理想的人格のこうした類型的表象は、クルアーンの神概念の最も根本的な要素の一つである。」11 だが、コルバンの見解では、一神論の公教的形式は、逆説的にも、二つの潜在的な奈落に陥る危険に曝されている。一方では、「同化」(キリスト教の受肉論のような受肉による擬人観)の危険がある。他方では、「棄権」(抽象的不可知論)の脅威にも直面している12。秘教的一神論は、これらの異端の二つの奈落をすり抜ける細い小道を歩んでゆく。

人格化された親密な神に関するイスラムの(理論的な)神秘主義的概念と、東洋の叡智の、つまり道教と仏教の伝統における存在論的な聖性のリアリティとの間に対話的関係を打ち立てることは、神学ないしは否定の道(否定神学)のある形式を採用することによって、(今日残念ながらアブラハムの諸国と息子たちの間で行き渡っている)神性の擬人的概念を純化することに貢献するかもしれない。他方で、人は、存在に関して人びとが抱いたさまざまな超越的領域を統合することにおけるイスラム世界とイランの霊的=神秘主義的な経験を、後期井筒が採用したアプローチからインスピレーションを受けることによって、極東の文化と精神性に紹介し、そうして、文明のこの圏域におけるありうべき無自覚の欠点に光を当てることができるだろう。

キリスト教の受肉の原理ないし教説に立ち臨んで、キリスト教の神秘家は、否定神学に依拠することにより、神の概念をコスモス的な聖なる存在者へと拡張する事を求めた。反対に、イスラム教の神秘家は、イスラムの神性の絶対的な抽象化と一性の原理に対して、クルアーンに記述されている神の人格化された形象と属性を強調する冒険を行った。

他方で、極東の存在論的で非・擬人観的な神秘主義(特に道教に結晶化されたものだが)は、明らかに、エックハルトの否定神学、ハイデガーの存在論、そして、イブン・アラービーにおける存在の(至高の)一性とある親和性を持っている。『スーフィズムと道教』において、井筒教授は、極東の存在論的神秘主義とイブン・アラービーの思想のありうべき親和性と比較について語っている。

とにかく、今日の我々の世界は、これまで以上に、ある平静さ(ゲラッセンハイト)を必要としており、そして、このグローバルな霊的対話において、東洋の叡智は、「末人」(凡庸な俗人)の使用の為に、思考を挑発する省察へと導くのである。だが、後期の井筒が指摘する通り、そうした対話の予備的条件は、共通の言語的基盤をもつことである13。この種の対話と秘教的・対話的なコミュニケーションの運命は、井筒の三肢に分節化された理論における共時的構造の東洋的記号学のうちに見いだされる、(哲学的な)東洋とその共通言語である。その井筒の理論は次のように構成される。1:同一性と無矛盾の原理に基づけられていて、判明に分離した、本質(意味と本性)の世界;2:宗教的・神秘的瞑想と修練、また、世界の脱構築や世界との意識の最初の邂逅によって獲得された知識の「否定」ないしはその構造的分節の完全な欠如;3:意識のこのゼロ点から出発することによる、「非=存在」、則ち神秘的で聖なるもの、あるいは一者の無媒介の自己分節を、新しく分節化して習得する新たな形式の再生。この段階では、万物は瞬くように現出して、柔軟かつ透明に相互浸透する。第二の段階では、経験をさらに深めることによって、言語の創造的で魔術的な形式が、誰の意味論的エネルギーが「絶対無分節者」の内にそれまで隠されていたかを語り出す。

コルバンと連帯しつつ、井筒は、意識と存在(本質)のこの深層領域を「オリエント」と呼び、道教、仏教における「現象の空無(vacuum of phenomena)」、ブラーフマー、スーフィズムにおける「神聖なる名」、ユダヤのカバラーにおける生命(セフィロト)等のさまざまな東洋的伝統の分析を引き受ける。そして、これらを、メルロ=ポンティ、ドゥルーズ、デリダといった現代の人物の作品に照らして評価する。

デリダの原=エクリチュールや原=痕跡は、井筒による第二段階の脱構築的分節と等しいものであり、これは、第一段階の分節の脱構築の後に来るものである。この段階では、「絶対無分節者」を通じて14、言語は終末論的な「散種」を始める。これは、デリダが「差異(différence)」の綴りの「e」を「差延(différAnce)」の「a」に変え、そうして、言語の差異化と遅延の両機能を指し示すモチーフないし能動的な名辞と転じさせたのと同じ仕方である。

場合によっては間違いも起こすであろう意味の似た語のこうした比較探究は、コルバンと井筒の批判的方法の特徴的性格に属するものであり、そこでは、混合主義を避ける為に、それぞれの概念はただ適切性の方法を適用するなかで各々のシステムにおいてのみ理解される。たとえ、こうした仕方で、異なる思想システムの間の比較が可能になるとしても。

結びの言葉として、次のことを指摘したい。いかなる文明と宗教に由来するにせよ、世界のあらゆる東洋人の共通の秘教的・霊的な方向が同一であるならば ― コルバンと井筒の両者に捧げて ― コルバンの有名なモットーを引用することは不適切ではあるまい。

「世界の東洋人よ、団結せよ!」

原註

1 マッソン―ウルセル以来の「比較的方法論」については:see H.CORBIN,

«Philosophie iranienne et philosophie comparée», Téhéran: Académie de Philosophie, 1976 , trad.pers., S. J.Tabatabai, p. 20

2 GA12, 91

3 P.Arjakovsky, F.Fédier, H.France-Lanord, Le Dictionnaire M.Heidegger, art. «Herméneutique», Paris: Cerf, 2013, p.60 ٣; + GREISCH, J., « Ontologie et temporalité », Paris :PUF, 1994

4 七つの地理的風土という古い概念を見よ。そこでは、世界が七つの等しい円環に分割される。

5 See Fadai Mehrabani, M., "Istâdan dar ân Suye marg" (stand beyond death, responses of H.

Corbin to Heidegger in perspective of the Shiite philosophy), Tehran: Ney, 2012

6 「機会論者であって、顕在的な『作用』における以外には神聖な因果性を知らないイスラムにとっては、ただ瞬間のみが存在する。hîn (Q. 21, III ;...), ân (Q. 16, 22), 瞬

き(clin d’œil )」;「それ故、時間は連続する『持続』ではなく、瞬間の『銀河系』の布置である(同様に、空間も存在しない。ただ点のみが存在する。)」; L.MASSIGNON, « Le

temps dans la pensée islamique » (Eranos, XX, 1952, pp.141-148), in Opera Minora de L.M., tome II, 1963, p. 606 Voir aussi: IQBAL, Muhammad, The reconstruction of religious thought in Islam, London: Oxford UP, 1934, rep. A.P.P., 1986, pp. 73 sq. (III.The Conception of God).

7 Cf. Reinhard May, „Ex oriente lux: Heideggers Werk unter ostasiatischem Einfluss“,

Stuttgart: Steiner Verlag Wiesbaden; Eng. Trans. Parkes, Graham, Heidegger's Hidden

Sources: East Asian Influences on His Work, Routledge, 1996 ; voir aussi LÖWITH, Karl, «Remarques sur la différence entre Orient et Occident», in Rev. «Le philosophoire, Labo. de philo.», N°41 (printemps 2014), Paris: Vrin, pp. 181-127

8 JAMBET, Ch., «Le soufisme entre L.Massignon et H.Corbin », in «Le Caché et l’Apparent», Paris l’Herne, 2003, p. 145 sq. ; + Opera Minora de L.M., tome II, 1963, Mystique musulmane et mystique chrétienne au Moyen Age, pp.480 sq. (Monisme testimonial/Monisme existentiel)

9 Ibid., t. II, 1963, P.481

10 Corbin, H., Le paradoe du monothéisme, Paris: l’Herne, 1981, pp. 14, 19

11 IQBAL, M., ibid., pp.59, 63

12 Corbin, 1981, ibid., p. 101, De la nécessité de l’angéloloie

13 「… 私がこの研究を始めたのは、アンリ・コルバン教授が『メタ歴史学における対話』と呼んだものが現代世界の状況でなにか緊急に必要とされているものだという確信にうながされてのことである。人間性の歴史のいかなる段階においてであれ、世界の諸国民のあいだの相互理解への必要が、我々の時代より強く感じられたことはなかった。『相互理解』は実現可能であろう ― あるいは少なくとも、理解可能である ― 生の異なる諸次元において。哲学的水準がそのうちでもっとも重要なものの一つである… この省察は、メタ歴史学的対話の可能性に関する極めて重要な方法論的問題へと我々を導く。その問題は、共通の言語体系の必要である。これは、正に「対話」の概念こそが二人の対話者の共通の言語の存在を前提するがゆえに、ひとえに当然の事

である。」T. IZUTSU, Sufism and Taoism: A Comparative Study of Key

Philosophical Concepts, Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1983, pp.469, 471 14 Cf. M.Dalissier, S.Nagai, Y.Sugimura, « Philosophie japonaise, Le néant, le monde et le corps», Paris : Vrin, 2013, p.362-364

井筒俊彦英文著作翻訳コレクション 全7巻(全8冊)| 慶應義塾大学出版会

井筒俊彦英文著作翻訳コレクション 全7巻(全8冊)| 慶應義塾大学出版会

慶應義塾大学出版会

Keio University Press

井筒俊彦英文著作翻訳コレクション 全7巻(全8冊)MENU

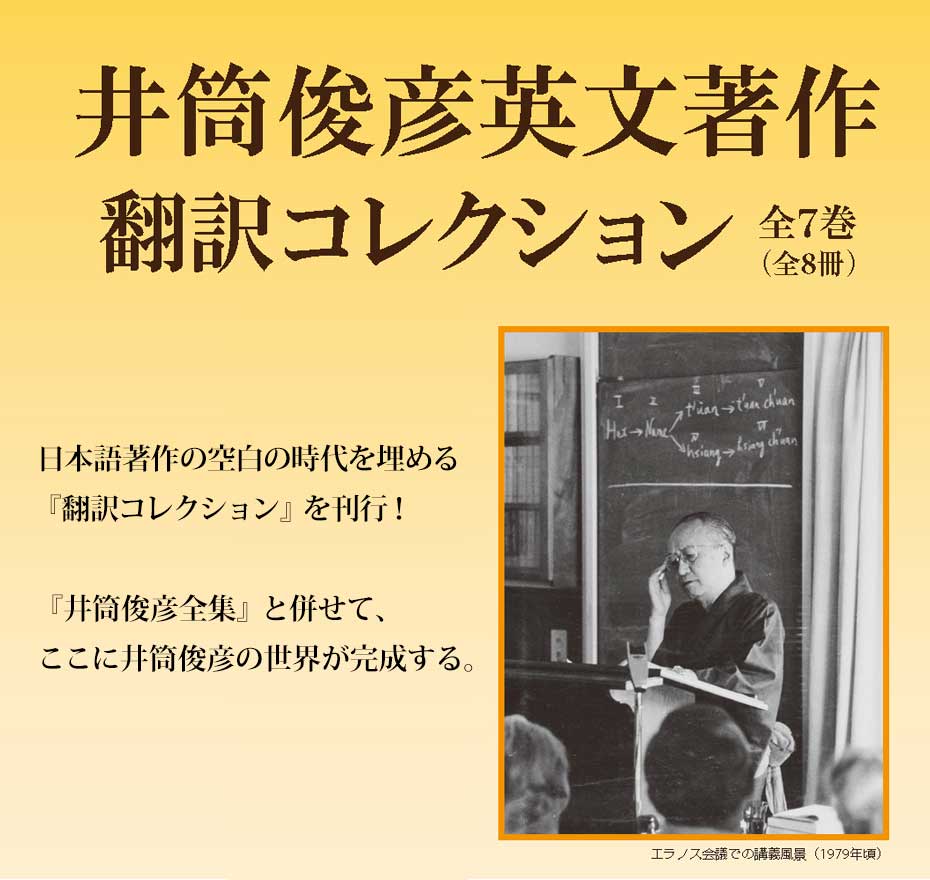

井筒俊彦英文著作翻訳コレクション 全7巻(全8冊)

■井筒俊彦英文著作翻訳コレクションのパンフレットはこちら

刊行にあたって

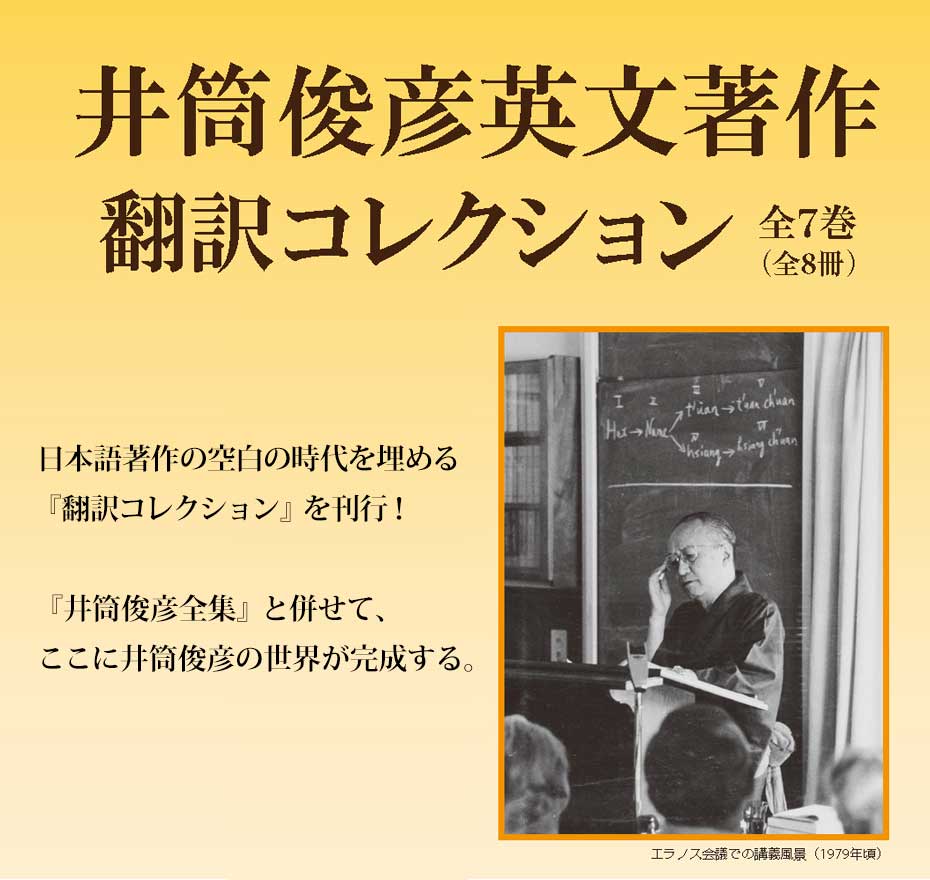

井筒俊彦(1914年―93年)の生誕100年を記念した『井筒俊彦全集』(全12巻・別巻、2013年-16年)の刊行によって、その思想の全体像が明らかになりつつあります。

しかし、井筒俊彦の生涯をひもとくと、1950年代半ばから約20年にわたって中近東、欧米で研究滞在し、日本語ではなく英文で多数の著作を発表した時代があります。この時期、井筒は日本語著作とは異なるアプローチでその思索を深化させ、構築していったのです。

本翻訳コレクションは、『井筒俊彦全集』と併せて、今日にいたるまで世界で読み続けられている井筒俊彦の英文代表著作を、本邦初訳で提供し、井筒哲学の全体像をより克明に明らかにするものです。

2017年4月

●『井筒俊彦全集』についてはこちらをご覧ください。

↑

本コレクションの特色

◎思索の「中期」にあたる1950年代から80年代にかけて井筒俊彦が英文で著し、世界で高く評価された代表著作全七作を、本邦初訳で提供。

◎井筒哲学の中心テーマでありながら日本語では発表することがなかった唯一の「言語論」であり、幻の連続講義「言語学概論」を基にした英文処女著作『言語と呪術』を収録。

◎世界のイスラーム研究を牽引し、今なお各国語への翻訳が進む“イスラーム三部作”を初めてまとめて提示する。

◎名訳『老子道徳経』とイスラーム三部作の完成を経て、中国とイスラームの神秘主義を架橋する“最大の大著”『スーフィズムと老荘思想』待望の邦訳。

◎主著『意識と本質』への礎となり、海外のオーディエンス向けに東洋思想を平明に語った講演集『エラノス会議』を収録。

◎最新の研究に基づいた精緻な校訂作業を行ない、原文に忠実かつ読みやすい日本語に翻訳。

◎読者の理解を助ける解説、索引付き。

↑

もう一人の井筒俊彦――英文著作をめぐって

安藤礼二

(文芸評論、多摩美術大学美術学部教授)

井筒俊彦(1914―93年)は、1962年のマギル大学への赴任から、1979年のイラン革命による日本への帰還に至るまで、20年近くにわたり、活動の場を海外に移した。年齢でいうと40代の半ば過ぎから60代の半ばまでである。この間の主要著作は、そのほとんどが英文で著された。英文著作の井筒俊彦は、日本語著作の井筒俊彦とは大きく異なっている。

なぜ、『コーラン』を選んだのか。井筒は英文著作で、明快に、こう答えてくれている。『コーラン』には、預言者を介して、人間の言葉でなく、神の言葉が記されていたからだ。預言者は、言葉の意味を変革できる特別な人間だった。なぜ、「東洋哲学」だったのか。エラノス会議に招かれ、そこで東洋をあらためて発見したからだ。エラノス会議で発表された井筒による英文の講演原稿(1967―82年)は、日本語による代表作『意識と本質』(1983年)の源泉となるとともに、それとは異なった東洋哲学へのもう一つのアプローチを示してくれている。そのはじまりにして帰結である、東洋の神秘主義思想たるタオイズムとイスラームの神秘主義思想たるスーフィズムを比較対照した英文による大著『スーフィズムと老荘思想』(初版1966―67年、改訂版1983年)がまとめられることになった。

井筒がはじめて英文で書き上げた著作、『言語と呪術』(1956年)は、井筒が海外へ旅立つ前に完成された。そこでは、人類学と心理学が同時に論じられ、『鏡の国のアリス』の登場人物ハンプティ・ダンプティとアラビアの預言者ムハンマドが同時に論じられていた。「未開社会」を統治する呪術的な言語と、幼児が獲得する始原的な言語は同様の構造をもっている。そうした原初の言葉にして魔術の言葉を用いて、ハンプティ・ダンプティは虚構の世界に、ムハンマドは現実の世界に、意味の革命をもたらしたのだ。

英文著作には、いまだ誰も見たことのない井筒俊彦が存在している。

↑

推薦のことば 「世界に輝くイスラーム三部作」

小杉 泰

(イスラーム学・中東地域研究、京都大学大学院アジア・アフリカ地域研究研究科教授)

井筒俊彦が英文で著したイスラーム三部作は、西洋的なイスラーム学の限界を超えて、真にグローバルな学知の時代を先導した名作である。アラビア語聖典の言語宇宙を内側から照射した『クルアーンにおける神と人間』、イスラーム独自の論理を解明し、東洋学に意味論的な大転換をもたらした『イスラーム神学における信の構造』、認識論を偏重する近代哲学に対して、存在論哲学の深淵を知らしめた『存在の概念と実在』。これらの名著によって巨星イヅツは世界に輝いた。さらに『スーフィズムと老荘思想』では、東洋の叡智・神秘哲学の神髄を比較考察するという難業で世界を驚嘆させた。

欧米のみならずイスラーム世界でも井筒イスラーム学は深甚な影響を与え、その名声によって日本がどれだけ恩恵を受けたか計り知れない。

本コレクションは、英文ゆえに日本発の世界的名著が日本の読者に届きにくいという逆説を解消するものであり、その意義は限りなく大きい。多言語の典拠と深い思索による原文を精確に日本語にした秀逸な訳業も、功績大である。イスラームの理解が喫緊の課題となっている今、二一世紀の吉報と言うべきであり、是非一読をお薦めしたい。

↑

推薦のことば 「井筒俊彦――彫琢としての翻訳」

中島隆博

(中国哲学・比較哲学、東京大学東洋文化研究所教授)

井筒俊彦は慶應義塾大学言語文化研究所の紀要において、1966年にスーフィズムを、1967年に老荘思想を論じる巻を刊行し、その改訂版が後に『スーフィズムと老荘思想』として書籍化された。

なぜこの二つの思想が同時に一冊にまとめ上げられなければならなかったのか。それは、井筒と深い親交のあった、イスラーム神秘思想研究者のアンリ・コルバンの「メタ歴史における対話」を、イスラームと中国思想の間で実践することによって、「永遠の哲学」に触れるためであった。

そのためには、老荘思想をイスラーム神秘思想であるスーフィズムに匹敵する神秘思想として彫琢する必要があった。井筒が『老子道徳経』の翻訳に取り組んだのはそのためであった。『老子道徳経』の第一章の井筒の翻訳を見ると「玄」を「神秘 mystery」そして「妙」を「驚異 wonder」と訳している。

井筒が尊敬していた鈴木大拙の神秘解釈が翻訳を通じて深められていったように、井筒の神秘哲学の深い機微を理解するためには、その彫琢としての翻訳の手つきこそが重要である。そのためにも、井筒俊彦英文著作翻訳コレクションの刊行は重要な貢献となる。

↑

井筒俊彦英文著作翻訳コレクション 概要

装丁 中垣信夫+中垣 呉[中垣デザイン事務所]

仕様 A5判上製

頁数 各巻約272~500頁

↑

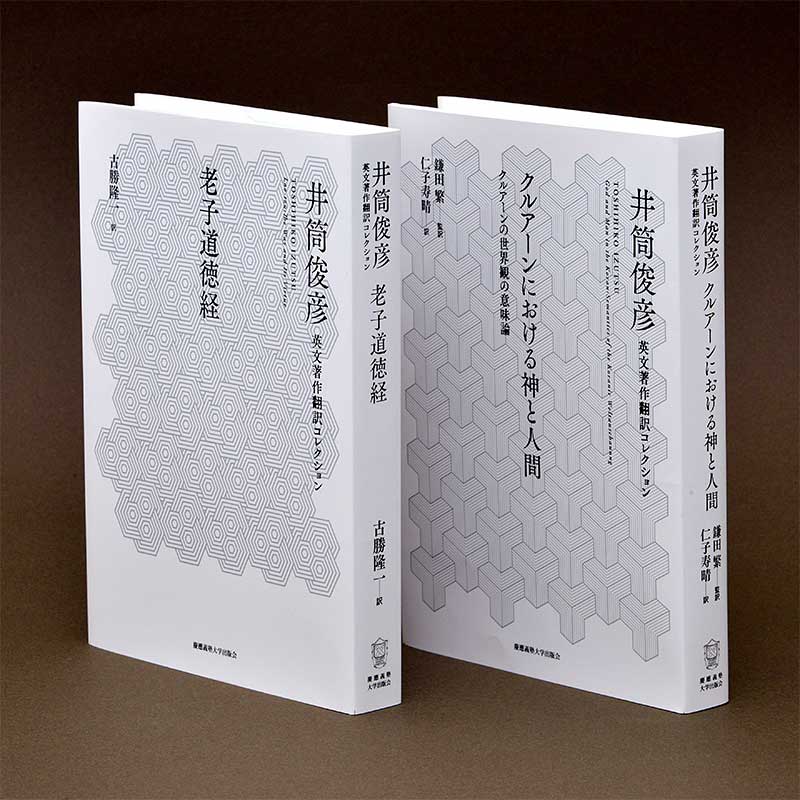

第1回配本 『老子道徳経』

[底本] Lao-tzŭ:The Way and Its Virtue

古勝隆一(中国古典学)訳

テヘラン滞在中、中国古典『老子道徳経』に注釈を施し英訳した遺稿の邦訳。井筒は伝統的な解釈に向き合い原典に忠実に言葉を選びながら、語り手の老子を、永遠なる「道」と一体化した一個の人格「私」として捉え、そこに流れる一貫した強力な思想を読みとる。井筒独自の解釈をもとに、これまでにない『老子道徳経』を読むことができる一冊。老子論としても秀逸な序文つき。

●256頁 本体3,800円

●目次・詳細はこちら

↑

第2回配本 『クルアーンにおける神と人間――クルアーンの世界観の意味論』

[底本] God and Man in the Koran: Semantics of the Koranic Weltanschauung

鎌田 繁(イスラーム神秘思想・シーア研究)監訳

仁子寿晴(イスラーム哲学・中国イスラーム思想)訳

日本人として初めてクルアーンを原典アラビア語から翻訳した井筒のクルアーン論。その聖典の中に示される「世界観」や、「創造主たる神」と「被造物たる人間」の関係を中心に、意味論的方法を用いて分析する。井筒が愛した無道時代の詩も満載された、イスラーム文化やクルアーンを理解するための最良の手引きとなる世界的名著。

●400頁 本体5,800円

●目次・詳細はこちら

↑

第3回配本 『存在の概念と実在性』

[底本] The Concept and Reality of Existence

鎌田 繁(イスラーム神秘思想・シーア研究)監訳

仁子寿晴(イスラーム哲学・中国イスラーム思想)訳

1971年、マギル大学時代に発表したイスラーム哲学に関する講演論文集。イスラーム形而上学的思惟の構造、東西の実存主義、存在一性論、さらにイラン哲学最大の思想家サブザワーリーの思想構造を、文献学的精密さと比較哲学的な方法論によって明快に分析する名論文四本を収録。井筒イスラーム論の真骨頂とも称される一冊。

●272頁 本体3,800円

●目次・詳細はこちら

↑

第4回配本 『イスラーム神学における信の構造――イーマーンとイスラームの意味論的分析』

[底本] The Concept of Belief in Islamic Theology:A Semantic Analysis of Iman and Islam

鎌田 繁(イスラーム神秘思想・シーア研究)監訳

仁子寿晴(イスラーム哲学・中国イスラーム思想)訳

橋爪 烈(カリフ制度史・イスラーム政治思想史研究)訳

初期イスラームの数世紀という思想史を考える上で最も興味深い時代に照明を当て、イスラームにとって最重要の概念「信仰」がいかに生まれ、発展し、理論的に完成していくのか歴史学的、文献学的に分析する。イスラーム神学とイスラームの基礎を知るために最適な一冊。

●440頁 本体5,800円

●目次・詳細はこちら

↑

第5回配本 『言語と呪術』

[底本] Language and Magic: Studies in the Magical Function of Speech

安藤礼二(文芸評論)訳

小野純一(イスラーム思想・哲学)

1956年に出版された英文処女著作。1949年から数年にわたり行われた伝説的な講義「言語学概論」唯一の成果であり、海外でも高い評価を得た。古今東西の古典に現れる言語の「呪術的」な機能を描き出し、それが今なお我々の中に息づくことを明らかにする。井筒言語哲学の出発点であり、後年の東洋哲学の構想へ向けて方法論的基盤となった名著。

●272頁 本体3,200円

●目次・詳細はこちら

↑

第6回配本 『東洋哲学の構造――エラノス会議講演集』

[底本] The Structure of Oriental Philosophy:Collected Papers of the Eranos Conference

澤井義次(宗教学・インド哲学)監訳

金子奈央(宗教学・東アジア仏教)訳

古勝隆一(中国古典学)訳

西村 玲(日本思想史・東アジア仏教思想)訳

思索の「中期」にあたる1967年から82年、井筒は日本と中国を中心とする東アジアの思想―禅、仏教、儒教、老荘思想など―を主題にエラノス会議で講演した。入念に準備された12回分の講演論文には、「東洋哲学」への一貫した思索が深まり、主著『意識と本質』へ成熟していく姿が見出せる。井筒読者必読の書。

●552頁 本体6,800円

●目次・詳細はこちら

↑

第7回配本 『スーフィズムと老荘思想 上――比較哲学試論』

[底本] Sufism and Taoism: A Comparative Study of Key Philosophical Concepts

仁子寿晴(イスラーム哲学・中国イスラーム思想)訳

『老子道徳経』を英訳し、意味論的方法を援用して大きな成果をあげたイスラーム三部作の発表後、井筒は、中国哲学最高峰の老荘とイスラーム神秘主義者イブン・アラビーの思想の底流に、共通した基本構造を見出し比較する、という壮大な試みに取り組んだ。長年の思索を新たな次元へと押し上げた井筒思想の堂々たる集大成。

●416頁 本体5,400円

●目次・詳細はこちら

↑

第7回配本 『スーフィズムと老荘思想 下――比較哲学試論』

[底本] Sufism and Taoism: A Comparative Study of Key Philosophical Concepts

仁子寿晴(イスラーム哲学・中国イスラーム思想)訳

『老子道徳経』を英訳し、意味論的方法を援用して大きな成果をあげたイスラーム三部作の発表後、井筒は、中国哲学最高峰の老荘とイスラーム神秘主義者イブン・アラビーの思想の底流に、共通した基本構造を見出し比較する、という壮大な試みに取り組んだ。長年の思索を新たな次元へと押し上げた井筒思想の堂々たる集大成。

●368頁 本体5,400円

●目次・詳細はこちら

↑

井筒俊彦の生涯

1914年5月4日、東京市四谷区に生まれる。

慶應義塾大学で西脇順三郎に師事し、言語学者として出発。ギリシア神秘思想史、ロシア文学などを講義するかたわら、1941年『アラビア思想史』、49年『神秘哲学』、50 年『アラビア語入門』、51年『露西亜文学』など初期代表著作を刊行。

1949年から開始された連続講義「言語学概論」をもとに56年Language and Magic(『言語と呪術』)を発表。同書によりローマン・ヤコブソンの推薦を得てロックフェラー財団フェローとして59 年から中近東・欧米での研究生活に入る。59 年The Structure of the Ethical Terms in the Koran(『意味の構造』として『井筒俊彦全集』第11巻に収録)を刊行。

1960年代からマギル大学やイラン王立哲学アカデミーを中心に研究や講演、執筆活動に従事、64年God and Man in the Koran(『クルアーンにおける神と人間』)、65年 The Concept of Belief in Islamic Theology(『イスラーム神学における信の構造』)、66年-67年 A Comparative Study of the Key Philosophical Concepts in Sufism and Taoism(『スーフィズムと老荘思想』上下巻。83年に改訂版)、71年 The Concept and Reality of Existence(『存在の概念と実在』)など英文著作を精力的に発表する。

1967年から82年までほぼ毎年エラノス会議で、老荘思想や禅、儒教など東洋哲学についての講演を行ない、計12回の講演は歿後 The Structure of Oriental Philosophy: Collected Papers of the Eranos Conference (『エラノス講演―東洋哲学講演集』)としてまとめられた。

また、テヘランでは『老子道徳経』を中国語から英語に翻訳し刊行する予定だったが、1979年2月イラン革命激化のため日本に帰国。歿後Lao-tzǔ: The Way and Its Virtue として刊行された。

帰国後は、長年の海外での研究成果による独自の哲学を日本語で著述することを決意、83年『意識と本質』、85年『意味の深みへ』、89年『コスモスとアンチコスモス』、91年『超越のことば』、93年絶筆となった『意識の形而上学』などの代表著作を発表した。

1982年日本学士院会員、毎日出版文化賞、83年朝日賞受賞。93年鎌倉の自宅で死去。

●「井筒俊彦」に関する情報や、「井筒俊彦入門」はこちら

当コーナーは、哲学者、言語学者、イスラーム学者として知られる「井筒俊彦」の入門ページです。

若松英輔氏による多角的な視点から井筒俊彦に関するエッセイをお届けします。

慶應義塾大学出版会

Keio University Press

井筒俊彦英文著作翻訳コレクション 全7巻(全8冊)MENU

井筒俊彦英文著作翻訳コレクション 全7巻(全8冊)

■井筒俊彦英文著作翻訳コレクションのパンフレットはこちら

刊行にあたって

井筒俊彦(1914年―93年)の生誕100年を記念した『井筒俊彦全集』(全12巻・別巻、2013年-16年)の刊行によって、その思想の全体像が明らかになりつつあります。

しかし、井筒俊彦の生涯をひもとくと、1950年代半ばから約20年にわたって中近東、欧米で研究滞在し、日本語ではなく英文で多数の著作を発表した時代があります。この時期、井筒は日本語著作とは異なるアプローチでその思索を深化させ、構築していったのです。

本翻訳コレクションは、『井筒俊彦全集』と併せて、今日にいたるまで世界で読み続けられている井筒俊彦の英文代表著作を、本邦初訳で提供し、井筒哲学の全体像をより克明に明らかにするものです。

2017年4月

●『井筒俊彦全集』についてはこちらをご覧ください。

↑

本コレクションの特色

◎思索の「中期」にあたる1950年代から80年代にかけて井筒俊彦が英文で著し、世界で高く評価された代表著作全七作を、本邦初訳で提供。

◎井筒哲学の中心テーマでありながら日本語では発表することがなかった唯一の「言語論」であり、幻の連続講義「言語学概論」を基にした英文処女著作『言語と呪術』を収録。

◎世界のイスラーム研究を牽引し、今なお各国語への翻訳が進む“イスラーム三部作”を初めてまとめて提示する。

◎名訳『老子道徳経』とイスラーム三部作の完成を経て、中国とイスラームの神秘主義を架橋する“最大の大著”『スーフィズムと老荘思想』待望の邦訳。

◎主著『意識と本質』への礎となり、海外のオーディエンス向けに東洋思想を平明に語った講演集『エラノス会議』を収録。

◎最新の研究に基づいた精緻な校訂作業を行ない、原文に忠実かつ読みやすい日本語に翻訳。

◎読者の理解を助ける解説、索引付き。

↑

もう一人の井筒俊彦――英文著作をめぐって

安藤礼二

(文芸評論、多摩美術大学美術学部教授)

井筒俊彦(1914―93年)は、1962年のマギル大学への赴任から、1979年のイラン革命による日本への帰還に至るまで、20年近くにわたり、活動の場を海外に移した。年齢でいうと40代の半ば過ぎから60代の半ばまでである。この間の主要著作は、そのほとんどが英文で著された。英文著作の井筒俊彦は、日本語著作の井筒俊彦とは大きく異なっている。

なぜ、『コーラン』を選んだのか。井筒は英文著作で、明快に、こう答えてくれている。『コーラン』には、預言者を介して、人間の言葉でなく、神の言葉が記されていたからだ。預言者は、言葉の意味を変革できる特別な人間だった。なぜ、「東洋哲学」だったのか。エラノス会議に招かれ、そこで東洋をあらためて発見したからだ。エラノス会議で発表された井筒による英文の講演原稿(1967―82年)は、日本語による代表作『意識と本質』(1983年)の源泉となるとともに、それとは異なった東洋哲学へのもう一つのアプローチを示してくれている。そのはじまりにして帰結である、東洋の神秘主義思想たるタオイズムとイスラームの神秘主義思想たるスーフィズムを比較対照した英文による大著『スーフィズムと老荘思想』(初版1966―67年、改訂版1983年)がまとめられることになった。

井筒がはじめて英文で書き上げた著作、『言語と呪術』(1956年)は、井筒が海外へ旅立つ前に完成された。そこでは、人類学と心理学が同時に論じられ、『鏡の国のアリス』の登場人物ハンプティ・ダンプティとアラビアの預言者ムハンマドが同時に論じられていた。「未開社会」を統治する呪術的な言語と、幼児が獲得する始原的な言語は同様の構造をもっている。そうした原初の言葉にして魔術の言葉を用いて、ハンプティ・ダンプティは虚構の世界に、ムハンマドは現実の世界に、意味の革命をもたらしたのだ。

英文著作には、いまだ誰も見たことのない井筒俊彦が存在している。

↑

推薦のことば 「世界に輝くイスラーム三部作」

小杉 泰

(イスラーム学・中東地域研究、京都大学大学院アジア・アフリカ地域研究研究科教授)

井筒俊彦が英文で著したイスラーム三部作は、西洋的なイスラーム学の限界を超えて、真にグローバルな学知の時代を先導した名作である。アラビア語聖典の言語宇宙を内側から照射した『クルアーンにおける神と人間』、イスラーム独自の論理を解明し、東洋学に意味論的な大転換をもたらした『イスラーム神学における信の構造』、認識論を偏重する近代哲学に対して、存在論哲学の深淵を知らしめた『存在の概念と実在』。これらの名著によって巨星イヅツは世界に輝いた。さらに『スーフィズムと老荘思想』では、東洋の叡智・神秘哲学の神髄を比較考察するという難業で世界を驚嘆させた。

欧米のみならずイスラーム世界でも井筒イスラーム学は深甚な影響を与え、その名声によって日本がどれだけ恩恵を受けたか計り知れない。

本コレクションは、英文ゆえに日本発の世界的名著が日本の読者に届きにくいという逆説を解消するものであり、その意義は限りなく大きい。多言語の典拠と深い思索による原文を精確に日本語にした秀逸な訳業も、功績大である。イスラームの理解が喫緊の課題となっている今、二一世紀の吉報と言うべきであり、是非一読をお薦めしたい。

↑

推薦のことば 「井筒俊彦――彫琢としての翻訳」

中島隆博

(中国哲学・比較哲学、東京大学東洋文化研究所教授)

井筒俊彦は慶應義塾大学言語文化研究所の紀要において、1966年にスーフィズムを、1967年に老荘思想を論じる巻を刊行し、その改訂版が後に『スーフィズムと老荘思想』として書籍化された。

なぜこの二つの思想が同時に一冊にまとめ上げられなければならなかったのか。それは、井筒と深い親交のあった、イスラーム神秘思想研究者のアンリ・コルバンの「メタ歴史における対話」を、イスラームと中国思想の間で実践することによって、「永遠の哲学」に触れるためであった。

そのためには、老荘思想をイスラーム神秘思想であるスーフィズムに匹敵する神秘思想として彫琢する必要があった。井筒が『老子道徳経』の翻訳に取り組んだのはそのためであった。『老子道徳経』の第一章の井筒の翻訳を見ると「玄」を「神秘 mystery」そして「妙」を「驚異 wonder」と訳している。

井筒が尊敬していた鈴木大拙の神秘解釈が翻訳を通じて深められていったように、井筒の神秘哲学の深い機微を理解するためには、その彫琢としての翻訳の手つきこそが重要である。そのためにも、井筒俊彦英文著作翻訳コレクションの刊行は重要な貢献となる。

↑

井筒俊彦英文著作翻訳コレクション 概要

装丁 中垣信夫+中垣 呉[中垣デザイン事務所]

仕様 A5判上製

頁数 各巻約272~500頁

↑

第1回配本 『老子道徳経』

[底本] Lao-tzŭ:The Way and Its Virtue

古勝隆一(中国古典学)訳

テヘラン滞在中、中国古典『老子道徳経』に注釈を施し英訳した遺稿の邦訳。井筒は伝統的な解釈に向き合い原典に忠実に言葉を選びながら、語り手の老子を、永遠なる「道」と一体化した一個の人格「私」として捉え、そこに流れる一貫した強力な思想を読みとる。井筒独自の解釈をもとに、これまでにない『老子道徳経』を読むことができる一冊。老子論としても秀逸な序文つき。

●256頁 本体3,800円

●目次・詳細はこちら

↑

第2回配本 『クルアーンにおける神と人間――クルアーンの世界観の意味論』

[底本] God and Man in the Koran: Semantics of the Koranic Weltanschauung

鎌田 繁(イスラーム神秘思想・シーア研究)監訳

仁子寿晴(イスラーム哲学・中国イスラーム思想)訳

日本人として初めてクルアーンを原典アラビア語から翻訳した井筒のクルアーン論。その聖典の中に示される「世界観」や、「創造主たる神」と「被造物たる人間」の関係を中心に、意味論的方法を用いて分析する。井筒が愛した無道時代の詩も満載された、イスラーム文化やクルアーンを理解するための最良の手引きとなる世界的名著。

●400頁 本体5,800円

●目次・詳細はこちら

↑

第3回配本 『存在の概念と実在性』

[底本] The Concept and Reality of Existence

鎌田 繁(イスラーム神秘思想・シーア研究)監訳

仁子寿晴(イスラーム哲学・中国イスラーム思想)訳

1971年、マギル大学時代に発表したイスラーム哲学に関する講演論文集。イスラーム形而上学的思惟の構造、東西の実存主義、存在一性論、さらにイラン哲学最大の思想家サブザワーリーの思想構造を、文献学的精密さと比較哲学的な方法論によって明快に分析する名論文四本を収録。井筒イスラーム論の真骨頂とも称される一冊。

●272頁 本体3,800円

●目次・詳細はこちら

↑

第4回配本 『イスラーム神学における信の構造――イーマーンとイスラームの意味論的分析』

[底本] The Concept of Belief in Islamic Theology:A Semantic Analysis of Iman and Islam

鎌田 繁(イスラーム神秘思想・シーア研究)監訳

仁子寿晴(イスラーム哲学・中国イスラーム思想)訳

橋爪 烈(カリフ制度史・イスラーム政治思想史研究)訳

初期イスラームの数世紀という思想史を考える上で最も興味深い時代に照明を当て、イスラームにとって最重要の概念「信仰」がいかに生まれ、発展し、理論的に完成していくのか歴史学的、文献学的に分析する。イスラーム神学とイスラームの基礎を知るために最適な一冊。

●440頁 本体5,800円

●目次・詳細はこちら

↑

第5回配本 『言語と呪術』

[底本] Language and Magic: Studies in the Magical Function of Speech

安藤礼二(文芸評論)訳

小野純一(イスラーム思想・哲学)

1956年に出版された英文処女著作。1949年から数年にわたり行われた伝説的な講義「言語学概論」唯一の成果であり、海外でも高い評価を得た。古今東西の古典に現れる言語の「呪術的」な機能を描き出し、それが今なお我々の中に息づくことを明らかにする。井筒言語哲学の出発点であり、後年の東洋哲学の構想へ向けて方法論的基盤となった名著。

●272頁 本体3,200円

●目次・詳細はこちら

↑

第6回配本 『東洋哲学の構造――エラノス会議講演集』

[底本] The Structure of Oriental Philosophy:Collected Papers of the Eranos Conference

澤井義次(宗教学・インド哲学)監訳

金子奈央(宗教学・東アジア仏教)訳

古勝隆一(中国古典学)訳

西村 玲(日本思想史・東アジア仏教思想)訳

思索の「中期」にあたる1967年から82年、井筒は日本と中国を中心とする東アジアの思想―禅、仏教、儒教、老荘思想など―を主題にエラノス会議で講演した。入念に準備された12回分の講演論文には、「東洋哲学」への一貫した思索が深まり、主著『意識と本質』へ成熟していく姿が見出せる。井筒読者必読の書。

●552頁 本体6,800円

●目次・詳細はこちら

↑

第7回配本 『スーフィズムと老荘思想 上――比較哲学試論』

[底本] Sufism and Taoism: A Comparative Study of Key Philosophical Concepts

仁子寿晴(イスラーム哲学・中国イスラーム思想)訳

『老子道徳経』を英訳し、意味論的方法を援用して大きな成果をあげたイスラーム三部作の発表後、井筒は、中国哲学最高峰の老荘とイスラーム神秘主義者イブン・アラビーの思想の底流に、共通した基本構造を見出し比較する、という壮大な試みに取り組んだ。長年の思索を新たな次元へと押し上げた井筒思想の堂々たる集大成。

●416頁 本体5,400円

●目次・詳細はこちら

↑

第7回配本 『スーフィズムと老荘思想 下――比較哲学試論』

[底本] Sufism and Taoism: A Comparative Study of Key Philosophical Concepts

仁子寿晴(イスラーム哲学・中国イスラーム思想)訳

『老子道徳経』を英訳し、意味論的方法を援用して大きな成果をあげたイスラーム三部作の発表後、井筒は、中国哲学最高峰の老荘とイスラーム神秘主義者イブン・アラビーの思想の底流に、共通した基本構造を見出し比較する、という壮大な試みに取り組んだ。長年の思索を新たな次元へと押し上げた井筒思想の堂々たる集大成。

●368頁 本体5,400円

●目次・詳細はこちら

↑

井筒俊彦の生涯

1914年5月4日、東京市四谷区に生まれる。

慶應義塾大学で西脇順三郎に師事し、言語学者として出発。ギリシア神秘思想史、ロシア文学などを講義するかたわら、1941年『アラビア思想史』、49年『神秘哲学』、50 年『アラビア語入門』、51年『露西亜文学』など初期代表著作を刊行。

1949年から開始された連続講義「言語学概論」をもとに56年Language and Magic(『言語と呪術』)を発表。同書によりローマン・ヤコブソンの推薦を得てロックフェラー財団フェローとして59 年から中近東・欧米での研究生活に入る。59 年The Structure of the Ethical Terms in the Koran(『意味の構造』として『井筒俊彦全集』第11巻に収録)を刊行。

1960年代からマギル大学やイラン王立哲学アカデミーを中心に研究や講演、執筆活動に従事、64年God and Man in the Koran(『クルアーンにおける神と人間』)、65年 The Concept of Belief in Islamic Theology(『イスラーム神学における信の構造』)、66年-67年 A Comparative Study of the Key Philosophical Concepts in Sufism and Taoism(『スーフィズムと老荘思想』上下巻。83年に改訂版)、71年 The Concept and Reality of Existence(『存在の概念と実在』)など英文著作を精力的に発表する。

1967年から82年までほぼ毎年エラノス会議で、老荘思想や禅、儒教など東洋哲学についての講演を行ない、計12回の講演は歿後 The Structure of Oriental Philosophy: Collected Papers of the Eranos Conference (『エラノス講演―東洋哲学講演集』)としてまとめられた。

また、テヘランでは『老子道徳経』を中国語から英語に翻訳し刊行する予定だったが、1979年2月イラン革命激化のため日本に帰国。歿後Lao-tzǔ: The Way and Its Virtue として刊行された。

帰国後は、長年の海外での研究成果による独自の哲学を日本語で著述することを決意、83年『意識と本質』、85年『意味の深みへ』、89年『コスモスとアンチコスモス』、91年『超越のことば』、93年絶筆となった『意識の形而上学』などの代表著作を発表した。

1982年日本学士院会員、毎日出版文化賞、83年朝日賞受賞。93年鎌倉の自宅で死去。

●「井筒俊彦」に関する情報や、「井筒俊彦入門」はこちら

当コーナーは、哲学者、言語学者、イスラーム学者として知られる「井筒俊彦」の入門ページです。

若松英輔氏による多角的な視点から井筒俊彦に関するエッセイをお届けします。

2022/07/26

Izutsu. Language and Magic Studies in the Magical Function of Speech: Toshihiko Izutsu: Amazon.com: Books

Language and Magic Studies in the Magical Function of Speech: Toshihiko Izutsu: Amazon.com: Books

See this image

See this image

Language and Magic Studies in the Magical Function of Speech Paperback – January 1, 2012

by Toshihiko Izutsu (Author)

4.0 out of 5 stars 1 rating

See all formats and editions

Paperback

$87.79

3 New from $85.24

The power of language has come to hold the central position in our conception of human mentality. Today, the man in the street has realised with astonishment how easy it is to be deceived and misled by words. The 'magical' power of the word has caught the attention of those who explore the nature of the human mind and the structure of human knowledge. This work by the late Japanese scholar, first published in 1956, tackles this complex and difficult subject. He studies the worldwide belief in the magical power of language, and examines its influence on man's thought and action. The purpose of the author in this book is to study the world-wide and world-old belief in the magical power of language, to examine its influence on the ways of thinking and acting of man, and finally to carry out an inquiry, as systematically as may be, into the nature and origin of the intimate connection between magic and speech. About The Author Toshihiko Izutsu was Professor Emeritus at Keio University in Japan and an outstanding authority in the metaphysical and philosophical wisdom schools of Islamic Sufism, Hindu Advaita Vedanta, Mahayana Buddhism (particularly Zen), and Philosophical Taoism. Fluent in over 30 languages, including Arabic, Persian, Sanskrit, Pali, Chinese, Japanese, Russian and Greek, his peripatetic research in such places as the Middle East (especially Iran), India, Europe, North America, and Asia were undertaken with a view to developing a meta-philosophical approach to comparative religion based upon a rigorous linguistic study of traditional metaphysical texts. Izutsu often stated his belief that harmony could be fostered between peoples by demonstrating that many beliefs with which a community identified itself could be found, though perhaps masked in a different form, in the metaphysics of another, very different community.

Read less

Report incorrect product information.

Publisher

Islamic Book Trust

Publication date

January 1, 2012

Next page

Customers who viewed this item also viewed

Page 1 of 2Page 1 of 2

Previous page

Sufism and Taoism: A Comparative Study of Key Philosophical Concepts

Toshihiko Izutsu

4.9 out of 5 stars 40

Paperback

30 offers from $26.68

Toward a Philosophy of Zen Buddhism

Toshihiko Izutsu

4.2 out of 5 stars 13

Paperback

30 offers from $13.00

The Theory of Beauty in the Classical Aesthetics of Japan

T. Izutsu

4.4 out of 5 stars 4

See this image

See this imageLanguage and Magic Studies in the Magical Function of Speech Paperback – January 1, 2012

by Toshihiko Izutsu (Author)

4.0 out of 5 stars 1 rating

See all formats and editions

Paperback

$87.79

3 New from $85.24

The power of language has come to hold the central position in our conception of human mentality. Today, the man in the street has realised with astonishment how easy it is to be deceived and misled by words. The 'magical' power of the word has caught the attention of those who explore the nature of the human mind and the structure of human knowledge. This work by the late Japanese scholar, first published in 1956, tackles this complex and difficult subject. He studies the worldwide belief in the magical power of language, and examines its influence on man's thought and action. The purpose of the author in this book is to study the world-wide and world-old belief in the magical power of language, to examine its influence on the ways of thinking and acting of man, and finally to carry out an inquiry, as systematically as may be, into the nature and origin of the intimate connection between magic and speech. About The Author Toshihiko Izutsu was Professor Emeritus at Keio University in Japan and an outstanding authority in the metaphysical and philosophical wisdom schools of Islamic Sufism, Hindu Advaita Vedanta, Mahayana Buddhism (particularly Zen), and Philosophical Taoism. Fluent in over 30 languages, including Arabic, Persian, Sanskrit, Pali, Chinese, Japanese, Russian and Greek, his peripatetic research in such places as the Middle East (especially Iran), India, Europe, North America, and Asia were undertaken with a view to developing a meta-philosophical approach to comparative religion based upon a rigorous linguistic study of traditional metaphysical texts. Izutsu often stated his belief that harmony could be fostered between peoples by demonstrating that many beliefs with which a community identified itself could be found, though perhaps masked in a different form, in the metaphysics of another, very different community.

Read less

Report incorrect product information.

Publisher

Islamic Book Trust

Publication date

January 1, 2012

Next page

Customers who viewed this item also viewed

Page 1 of 2Page 1 of 2

Previous page

Sufism and Taoism: A Comparative Study of Key Philosophical Concepts

Toshihiko Izutsu

4.9 out of 5 stars 40

Paperback

30 offers from $26.68

Toward a Philosophy of Zen Buddhism

Toshihiko Izutsu

4.2 out of 5 stars 13

Paperback

30 offers from $13.00

The Theory of Beauty in the Classical Aesthetics of Japan

T. Izutsu

4.4 out of 5 stars 4

Language and Magic: Studies in the Magical Function of Speech

by Toshihiko Izutsu

4.14 · Rating details · 7 ratings · 2 reviews

The power of language has come to hold the central position in our conception of human mentality. Today, the man in the street has realised with astonishment how easy it is to be deceived and misled by words. The 'magical' power of the word has caught the attention of those who explore the nature of the human mind and the structure of human knowledge. This work by the late Japanese scholar, first published in 1956, tackles this complex and difficult subject. He studies the worldwide belief in the magical power of language, and examines its influence on man's thought and action. The purpose of the author in this book is to study the world-wide and world-old belief in the magical power of language, to examine its influence on the ways of thinking and acting of man, and finally to carry out an inquiry, as systematically as may be, into the nature and origin of the intimate connection between magic and speech. About The Author Toshihiko Izutsu was Professor Emeritus at Keio University in Japan and an outstanding authority in the metaphysical and philosophical wisdom schools of Islamic Sufism, Hindu Advaita Vedanta, Mahayana Buddhism (particularly Zen), and Philosophical Taoism. Fluent in over 30 languages, including Arabic, Persian, Sanskrit, Pali, Chinese, Japanese, Russian and Greek, his peripatetic research in such places as the Middle East (especially Iran), India, Europe, North America, and Asia were undertaken with a view to developing a meta-philosophical approach to comparative religion based upon a rigorous linguistic study of traditional metaphysical texts. Izutsu often stated his belief that harmony could be fostered between peoples by demonstrating that many beliefs with which a community identified itself could be found, though perhaps masked in a different form, in the metaphysics of another, very different community. (less)

GET A COPY

KoboOnline Stores ▾Book Links ▾

Paperback, 199 pages

Published 2012 by Islamic Book Trust (first published 1956)

==

Write a review

Mamluk Qayser

Feb 16, 2022Mamluk Qayser rated it really liked it

Shelves: 2022

This complex book sets out to delineate the magical nature of language.

Magical thinking, as often found in primitive societies, the peripheries of modern religions, or even in daily superstition thinking of the modern people could be loosely defined into the direct manifestation of effect via an indirect medium that is directly associated with the effect. An example would be the concept of "jinxing", where something actually happened when one actually speaks about it.

Izutsu strived to demonstrate that the magical nature of language is not based from fallacious thinking of men, but rise from the very nature of language itself.

Language as understood by the modern positivists as an activity embedded in logic. Monstrosities rose from their hapless quest for a logical structure of language, until Wittgenstein called it a day by deciding that language is an active activity, where no set-to-stone carved in it. We created rules for almost everything, but not everything. We set the ground rules in football in order for it to be playable, but not to an extent to exactly define how high the ball should go etc., as long as these peripheries questions do not interrupt with the game itself.

Language thus, is not a one-to-one function with rigid logical framework behind it. It is half-referential (as in denotative function, to directly refers to things concrete and experiential without), and also half-emotive (as in connotative function, to indirectly refers things without i.e. feelings, emotions, memories, poetic usage of language). When we speak of a thing, we not only isolate the thing and to highlight upon it its existence, but also to imbued it with webs of evocative information.

This active and fluid nature of language is what makes language magical in the sense of creating awe behind lines of poetry of ejaculations of emotion. Those are the magical properties of language in our daily lives.

Isutzu also offers a theory of origin of language, not from communicative purposes, but rather that language originated from a festal origin. The primitive people would gather together in rituals, ceremonies that would facilitate the heightening of emotion. These rituals then acts as a medium where heightening of emotions could be then released with vocal raptures, allowing first associations between meaning and vocal ejaculations. It is the symbolic nature of men's mind that allows them to, in a way, pregnant the early gesticulations with meaning. (less)

Istvan Zoltan

Feb 06, 2020Istvan Zoltan rated it liked it

Shelves: 20th-century, big-picture-philosophy, history, non-fiction, philosophy, poetry, language

A very insightful book combining ideas from linguistics, anthropology and sociology. With great sensitivity Izutsu identifies several social practices and institutions in which our traditional ways of thinking, our inherited appreciation for rituals, form the basis of what and how we do.

===

Language and Magic: Studies in the Magical Function of Speech

by Toshihiko Izutsu

4.14 · Rating details · 7 ratings · 2 reviews

The power of language has come to hold the central position in our conception of human mentality. Today, the man in the street has realised with astonishment how easy it is to be deceived and misled by words. The 'magical' power of the word has caught the attention of those who explore the nature of the human mind and the structure of human knowledge. This work by the late Japanese scholar, first published in 1956, tackles this complex and difficult subject. He studies the worldwide belief in the magical power of language, and examines its influence on man's thought and action. The purpose of the author in this book is to study the world-wide and world-old belief in the magical power of language, to examine its influence on the ways of thinking and acting of man, and finally to carry out an inquiry, as systematically as may be, into the nature and origin of the intimate connection between magic and speech. About The Author Toshihiko Izutsu was Professor Emeritus at Keio University in Japan and an outstanding authority in the metaphysical and philosophical wisdom schools of Islamic Sufism, Hindu Advaita Vedanta, Mahayana Buddhism (particularly Zen), and Philosophical Taoism. Fluent in over 30 languages, including Arabic, Persian, Sanskrit, Pali, Chinese, Japanese, Russian and Greek, his peripatetic research in such places as the Middle East (especially Iran), India, Europe, North America, and Asia were undertaken with a view to developing a meta-philosophical approach to comparative religion based upon a rigorous linguistic study of traditional metaphysical texts. Izutsu often stated his belief that harmony could be fostered between peoples by demonstrating that many beliefs with which a community identified itself could be found, though perhaps masked in a different form, in the metaphysics of another, very different community. (less)

GET A COPY

KoboOnline Stores ▾Book Links ▾

Paperback, 199 pages

Published 2012 by Islamic Book Trust (first published 1956)

ISBN9839541765 (ISBN13: 9789839541762)

Edition LanguageEnglish

Other Editions

None found

All Editions

...Less DetailEdit Details

EditMY ACTIVITY

Review of ISBN 9789839541762

Rating

1 of 5 stars2 of 5 stars3 of 5 stars4 of 5 stars5 of 5 stars

Shelves to-read edit

( 1404th )

Format Paperback edit

Status

April 19, 2022 – Shelved as: to-read

April 19, 2022 – Shelved

Review Write a review

comment

FRIEND REVIEWS

Recommend This Book None of your friends have reviewed this book yet.

READER Q&A

Ask the Goodreads community a question about Language and Magic

54355902. uy100 cr1,0,100,100

Ask anything about the book

Be the first to ask a question about Language and Magic

LISTS WITH THIS BOOK

This book is not yet featured on Listopia. Add this book to your favorite list »

COMMUNITY REVIEWS

Showing 1-35

Average rating4.14 · Rating details · 7 ratings · 2 reviews

Search review text

All Languages

More filters | Sort order

Sejin,

Sejin, start your review of Language and Magic: Studies in the Magical Function of Speech

Write a review

Mamluk Qayser

Feb 16, 2022Mamluk Qayser rated it really liked it

Shelves: 2022

This complex book sets out to delineate the magical nature of language.

Magical thinking, as often found in primitive societies, the peripheries of modern religions, or even in daily superstition thinking of the modern people could be loosely defined into the direct manifestation of effect via an indirect medium that is directly associated with the effect. An example would be the concept of "jinxing", where something actually happened when one actually speaks about it.

Izutsu strived to demonstrate that the magical nature of language is not based from fallacious thinking of men, but rise from the very nature of language itself.

Language as understood by the modern positivists as an activity embedded in logic. Monstrosities rose from their hapless quest for a logical structure of language, until Wittgenstein called it a day by deciding that language is an active activity, where no set-to-stone carved in it. We created rules for almost everything, but not everything. We set the ground rules in football in order for it to be playable, but not to an extent to exactly define how high the ball should go etc., as long as these peripheries questions do not interrupt with the game itself.

Language thus, is not a one-to-one function with rigid logical framework behind it. It is half-referential (as in denotative function, to directly refers to things concrete and experiential without), and also half-emotive (as in connotative function, to indirectly refers things without i.e. feelings, emotions, memories, poetic usage of language). When we speak of a thing, we not only isolate the thing and to highlight upon it its existence, but also to imbued it with webs of evocative information.

This active and fluid nature of language is what makes language magical in the sense of creating awe behind lines of poetry of ejaculations of emotion. Those are the magical properties of language in our daily lives.

Isutzu also offers a theory of origin of language, not from communicative purposes, but rather that language originated from a festal origin. The primitive people would gather together in rituals, ceremonies that would facilitate the heightening of emotion. These rituals then acts as a medium where heightening of emotions could be then released with vocal raptures, allowing first associations between meaning and vocal ejaculations. It is the symbolic nature of men's mind that allows them to, in a way, pregnant the early gesticulations with meaning. (less)

flag1 like · Like · comment · see review

Istvan Zoltan

Feb 06, 2020Istvan Zoltan rated it liked it

Shelves: 20th-century, big-picture-philosophy, history, non-fiction, philosophy, poetry, language

A very insightful book combining ideas from linguistics, anthropology and sociology. With great sensitivity Izutsu identifies several social practices and institutions in which our traditional ways of thinking, our inherited appreciation for rituals, form the basis of what and how we do.

flagLike · comment · see reviewNext page

Labels:

Sufism,

Toshihiko Izutsu,

수피즘

2022/07/25

Wakamatsu on Izutsu CH 04

Wakamatsu on Izutsu CH 04

CHAPTER FOUR

God's apostle to deliver the Koran to the world, was a nadhrr (admonisher). . . His mission as Prophet was spent in giving warnings." As Izutsu's words suggest, the reason Islam became a religion was only because these warnings went unheeded. The Koran is a compendium of admonitions. If the experiences of Muhammad that came to fruition in the Koran were truly mystical experiences, the words that were spoken could not have been those of Muiammad the human being. The reason the Koran is holy scripture is not because the Prophet Mulammad had a part to play in it, but rather because Muhammad annihilated himself to the point that even his afterimage disappeared and thereby became the passageway for the WORD of Cod.

It was Mularnmad's insight as Prophet that it was not the Jews or the Christians, but he himself who had inherited in its entirety the spirituality of Abraham and Jesus.

It had to be a religion that was neither Judaism nor Christianity, a far purer, far more authentic Israelite religion than those historical religions that had gone astray. It had to be a religion that transcended history. truly the direct embodiment of "eternal religion" (ad-din

al.qaiyirn)... . Islam s not a new religion; it was essentially an old

religion.

An "eternal religion" —this is perhaps the original nature of Islam that flows from its U rgrund, but it also clearly expresses what Izutsu saw in Islam. A study of Cod that transcends sects and denominations can only be articulated by someone who has had an experience of God that transcended religions. The "eternal religion" of which Izutsu speaks here is identical to Yoshinori Moroi's llrreligion.

(A 1A 11 I 11 it I I\ I.

Catholicism

The Saint and the Poet

IN THE FIRST CHAPTER 1 mentioned that, when Izutsu was writing Shinpi Ietsugaku 0949: Philosophy of mysticism), he believed that Greek mystic philosophy had not been brought to completion by Plotinus, but rather had flourished under, and reached perfection in, Christian mysticism. The following passage is from the preface written in 1978 at the time a revised version of Shin p1 tetszagaku was published.

Perhaps as a reaction against the atmosphere at home, where an exces-sivclv rigid Oriental mentailti prevailed. I was far more fascinated with the West than with the East. In particular. I was deeply affected by ancient Greek philosophy and Creek literature. But that was not all; I was possessed by the highly tendentious view that Greek mysticism as such had not ended, but had entered Christianity and undergone its hue development, reaching its culmination in the Spanish Cannclitc Order's mysticism of love and in John of the Cross especially.'

If Izutsu was saying that mystic philosophy's only legitimate line of descent is the one that leads to John of the Cross. then he must accept the criticism that this was indeed a "tendentious" notion, Yet it would be no one other than Izutsu himself who, in his later years, oiild clearly show that not only Islam and Buddhism hut the other Oriental

CHAPTER FOUR

A CONTEMPORARY AND THE BIOGRAPHY OF WE PROPHET

Why do people need to believe in a religion? How can they catch a glimpse of the trutfi of religion without delving deeply into the inevitable problem of the subject of-faith? Nowadays religion may be nothing more than a humanistic concept, and yet "it is obvious that religious people do not fear being included in this term. That is because when it comes to the position of an inexhaustible subject it is intolerable that the pressing problem of their own souls should be flattened out and reduced to a simple objective concept." Religion is, after all, he says, nothing other than the "locus of the individual subject"' It would be wrong to see in this statement the narrow-minded view that only believers can discuss religion. The very idea of a person converting to some religion or other already relativizes or standardizes religion and ignores the "locus of the individual subject," which is faith.

Membership in a particular religion is not a problem. But if Moroi were asked whether it is impossible for someone who is not a seeker after transcendental Reality to discuss religion, he would probably say yes. "Such being the case, how would it be possible for them, when they try to discuss religion, to have a grasp of its true essence without reflecting on the living whole of it in conformity with their subjective life?" Moroi writes. "Serious inquiry into religion must be attempted by approaching its true nature with profound sympathy."6

At the time Shukyoteki shut aisei no ronri was published, there were no authorial revisions; it was a posthumous work. If his study of the development of religious mysticism was his scholarly magnum opus, this posthumous book proves that Yoshinori Moroi was a rare individual thinker. He was also a philosopher who had the requisite background and ability to construct an ideological system rare for Japan.

In-depth discussions of mysticism, or what Izutsu calls the "mystical experience," inevitably delve into the origins of religion. Latent in such discussions is the question of whether human beings are capable of encountering and achieving union with God without the mediation of dogma. commandments, rituals, holy scriptures or faith-based communities such as churches and temples. This, in turn, is connected to the fundamental question of whether people can come in direct contact with the Transcendent without religion at all. When Christian scholastic theology entered a blind alley. Eckhart appeared and cleared the way for German mysticism. When lslm became inflexible in its interpretation of its doctrines and commandments, llallij appeared and revived the spirituality of Mul:iammad. Massignon saw a high degree of agreement in the spirituality of these two men. Just before his death Eckhart was accused of being a heretic; IIalhij was executed as a criminal. It was no accident that they both were shunned in their clay and met unfortunate ends. Both spoke words that broke through the confusion of their times and ushered in the light, but for those accustomed to darkness, the light may sometimes seem more like a threat than the bestowal of grace. Suhrawardi, the twelfth-century Persian who spoke of the metaphysics of light, was assassinated. His Japanese contemporary Hönen, the founder of the Jodo (Pure Land) school, in his later sears was exiled to an island, the virtual equivalent of the death penalty. Jesus was crucified, and most of his disciples ended their lives as niartvrs.

Yoshinori Moroi was a believer in Tenri-k-yr).'roshihiko Izutsu was a mystic who did not believe in any particular religion. The idea that Izutsu was a Muslim is nothing more than a myth. He was not. He did, however, have an incontrovertible experience of God. Philosophy for Izutsu would he nothing less than the way to verify this experience. That is the reason he was able to find traces of religion, i.e. faith, in ancient Greek philosophy. For Moroi and Izutsu, "mysticism" is not a word that signifies a particular ideology or set of beliefs; it is a straight road, an attitude toward life that regards the mysteries as the main source of righteousness. Mysticism does not reject faith-based communities. Rather, true mysticism serves as a matrix for them. Toward the end of his life, Bergson saw Catholicism as the perfect complement to Judaism and confessed his belief in it. What led him to Christianity were the mystics whom lie discussed in Ls deux sources de la morale €1 de la religion (1932; The Two Sources of Morality and Religion, iq;). For Bergson, a Jew, Christianity was not a new religion. Wasn't what he discovered in Catholicism, rather, a way of returning to the llrreligion?

In Shukvoteki shutaisei no ronri, Yoshinori Moroi discusses the topic of [Irreligion. Urreligion does not mean the oldest religion or primitive religion. It does not belong to a particular time, but exists

CHAPTER FOUR A CONTEMPORARY AND TIF HIOCLWHY OF THE PROPHET

in "time" in a qualitative sense. "Time" does not belong on a measurable temporal axis. J.M. MiThy said that what Dostoevsky depicted was beyond time rather than in time; Urreligion, too, implies nothing less than the existence of this kind of "time." It is also the dimension in which Eliade's homo religiosus lives. Mysticism breaks through spa-tio-temporal limitations and leads people to the site of ur-revelation. in other words, to the "now-ness" of tirreligion. If a true dialogue among religions is to come about, it will likely not OCCUI by haggling over dogma; it will be realized in the silence of the mystics.

The reason Yoshinori Moroi was able to have such a superb feeling for Islam is not unrelated to his being a believer in Tenri-kvo. The fact that it is a monotheism, the position and role of its founder and prophet, its holy land, and the details surrounding the origin of its sacred texts, their revelation and systematic compilation—a mere glance at this list shows that Tenri-kyö is far closer to Islam than it is to Christianity. rreflrjk,o is now engaged in an active dialogue with Catholicism, but if it were to attempt a similar dialogue with Islam. it is apt to discover a new dimension that it would be unable to find in its exchanges with Christianity.

Moroi's speculations on the persona of God, which he developed in his essay on Tenri-kvô dogmatic theology, could well be called an attempt to go beyond the veil of the denominations of world religions such as Judaism, Christianity and Islam and trace religions back to their divine origin. Yoshinori Moroi develops his argument using not only terms such as Creator and Savior for God's persona, but also Manifester, Protector, Revealer, Designator, Beginning of the World, All-Embracing One and Inspirer. As he describes it. Tenri-kyo is a monotheism pure and simple. As the works of Yoshinori Moroi make abundantly clear, the thesis that Japan is rooted in a polytheistic culture that is incompatible with monotheism is specious and naive. Had he been able to proceed further with his systematic construction of a Ten-rikvologv and a dogmatic theology of Ten ri-kyU. he might have shown analogies that transcend time and space between the Cod revealed in Japan and Jerusalem respectively.

What he never lost sight of was the relation of"analogy." An analogy basically connotes comparable phenomena. But these phenomena are not merely similar. If that were all, there probably would be no need to discuss them further. Analogy signifies that operations of a similar quality are unfolding dynamically among different entities. What Toshihiko Izutsu thoroughly explored in Sufism and Taoism is not that these two philosophical worldvicvs are similar. It is nothing less than to cause them both to manifest Oriental spirituality analogically.

The suggestion that monotheism is based on a paternal principle and polytheism on a maternal one has been heard many times. Some say that the God of the Koran is, first and foremost, a paternal Cod who causes fear and trembling. But seeing only fatherhood, the embodiment of sternness and judgment, in the omniscient, omnipotent one God denies God's perfection. This is not the true nature of God but only a graphic reflection of the limitations of the human beings who contemplate Cod. The following passage is found in Moral's essay on Tenri-kyo dogmatic theology: "Cod the Parent wished to save human beings from their many cares and sufferings and bestowed the merit of salvation by graciously appearing before them."17 Cod loves us as parents love their children; this view of God runs throughout Yoshinori Moroi's theology. It is perhaps for that reason that Ten ri-Iwo calls the Transcendent "God the Parent."

"A belief in the Cod of mercy's countenance of bright light, which is the converse of the Cod of wrath and outwardly a complete antithesis to it, is a fundamental characteristic of Judaic personal theism.

i'he Koran describes the terrih'ing Lord of judgment yet at the same time attempts to convey His joyful message as 'good news.' In fact, the boundless mercy and loving kindness of God are emphasized everywhere in the Koran." These are not the words of Yoshinori Moroi but of Toshihiko Izutsu in Mahometto.'8 If God willed it, the world would disappear in an instant. The fact that the world now exists is due to God's loving kindness. The God manifested in the Koran is a Cod of maternal mercy before being a God of judgment. This is the spirituality that Toshihiko Izutsu discovered in Islam at an early date. Like Pascal, he discovered what he had already known. It is fair to think that the God of mercy and loving kindness was, in fact, the spirituality of Toshihiko lzuu himself.

CHAPrFR FOUR

'Biography of the Prophet

4'

The use of '4Muharnmado" as the Japanese approximation of the Prophet's name is relatively recent. Japanese formerly referred to him as "Mahometto," perhaps following French usage. Toshihiko Izutsu's Mahometto came out in 1952, a year after Eliade's Chamanisme was published. In that same year, Yoshinori Moroi wrote a monograph entitled "Muhamaddo ni okeru shinpi taiken no mondai: genshi Isuramu no tassawuffu" (The question of Mtilamrnad's mystical experience: The flowering of taanwuf in early Islam). The following year, 1953, Yoshinori Moroi submitted his doctoral dissertation, Shukyo shin pishugi has-sei no kenkvu, which includes this essay, to the University of Tokyo. When the dissertation was published in 1966, the title was changed to "tile question of the Prophet Mul:iammad's mystical experience."

The question in point is found in Chapter 53 of the KOran.

In the name of Allah the Merciful, the Compassionate. I swear by the selling star, Your companion was not mistaken nor was he led astray. Nor does he speak out of self-indulgent emotions. It is, indeed, nothing other than a revelation that he reveals. The one of mighty power taught him. The one who has strength (taught him). And so he truly acquired skill. And he was on the highest level of the horizon and approached from there. And lie bowed. Thus, he was the distance of two bow-lengths or even nearer than that. Then he turned to his servant and revealed what he revealed. The latter's heart did not misrepresent what he saw. Do you, then, try to dispute with hirn about what he saw?'9

"This passage is extremely suggestive," Yoshinori Moroi writes. "In all the chapters of the Qur'an [Moroi's spelling], there is probably nothing like it that conveys such subtle information about the expeni-ence."2° These are strong words. Considering that the context in which they were written was a doctoral dissertation, we must read them as even further emphasizing what he felt in his innermost heart. The key to a basic understanding of the KOran is hidden in this passage, Moroi would perhaps say, and those who overlook it have lost sight of something important.

A CON1EMPORARY ANI) TilE BIOGRAPHY OF THE PROPHET

rll.lik Izutsu translated the Koran twice. The passage cited below is taken from volume 2 of the first version, published in 1958, vIiicli Yoshinori Moroi might have read. When the second translation came out, Moroi was already in the other world. Here is Toshihiko Izutsu's translation of the same passage.

In the name of the profoundly merciful, all-compassionate Allah. By the setting star...

Your colleague is not misguided; he is not mistaken. He is not babbling baseless fancies. These are all divine oracles that are being revealed. In the first place, the one who first taught (the revelation) to that man is the possessor of tcrrih'ing power, a lord excelling in intelligence. His shape distinctly caine into view far off beyond the high horizon, and, as he looked on, lie effortlessly, effortlessly descended and drew near; his nearness was almost that of two bows, no, perhaps even closer than that. iiicn it revealed the main purpose of the oracle to the manservant.

sWliv would the heart lie about what he certainly saw with his own eyes? Is it your intention to make this or that objection about what he ftdv saw?2'

It has to be said that Toshihiko Izutsu's translation is unique. And yet it is probably not enough to SCflSC only a difference in tone here. A fine translation is always an excellent commentary. Both translations faithfully convey the "readings" of the two men. The difference in their translations is, in other words, the difference in their personal experiences of Islam. I shall deal with this topic later when I discuss the Koran. The issue here is a different one.

As Yoshinori Moroi points out, the question is, "did Mubammad in fact see Allah?" or was it an angel that the Prophet saw. 'l'lie "shape [that) distinctly came into view far off beyond the high horizon" in Thshihiko Izutsu's translation, he would come to say, was the archangel Gabriel. Having reviewed the interpretations of B. Shricke and Josef Horovitz, Yoshinori Moroi came to the conclusion that what MuI.iam-iiiad saw was not Allah, as they had said, nor was it an angel. "It was Allah as the subject of the Allah nature."" The technical term "Allah nature" is unique to Yoshinori Moroi. Allah does not appear qua Allah;

CHAPTER FOLIR

A CONTEMPORARY AND THE ØK)CRAPHY O ThE pRoPiItr

human beings are iilcapablc of perceiving him through their senses. Even the Prophet is no exception. Cod is invisible and unknowable.

"When Paul was on the road to Damascus. he encountered a light, heard the voice of Jesus saying, "Why are you persecuting me?" and was knocked to the ground. Led by the hand, he entered the city. and for the next three days. his eyes saw nothing, and he was unable to eat or drink. The light that Paul saw was not God. God, who is infinite, is light, but that does not mean that light is God. Paul saw a light and heard Jesus voice. For Paul, God and Christ are synonymous. The mystery of Christianity resides in that synonymy. To borrow Yoshinori Morois words, one might say that this light was not Christ; it was his "Christ nature."

One wonders whether Toshihiko Izutsu might not have seen an "Allah nature" in Chapter 53 of the Koran. In later years, in the series of lectures published as Koran o yoniu (1983; Reading the Koran), he deals with this chapter as the classic example of Mul,iammad's vision experience.3 Although in his translations he regards the one who appeared as the archangel Gabriel, he adds the reservation that there is room for scholarly debate. But if it was not Gabriel, then a human being saw Allah, he says, and that causes problems from a theological perspective. He left no further comments on this subject. If he had gone on and done so, he might have developed an angelology, a theory of angels. "The only person able to respond to the call of the Western philosophical tradition and approach a solution to it head-on was St Thomas. Herein lies the profound historical significance of his speculations on angels."4 "The solution to it" is the question of the divine nature, i.e. the existence of an "Allah nature" that Yoshinori Moroi noted. Ever since the time of Shinpi tetsugaku, the problem of angels was on Izutsu's mind.

What are angels? The fact that angels are a vibrant reality not only in Christianity but also in lsIiii is evident from the preceding quotes; for Japanese, they may be easier to understand if we think of the Bodhi-sattvas, who are the attendants of Nyorai. Angels have no will of their own. They are messengers who convey God's will. For Toshihiko Izutsu, real angels always express "Christ nature" and "Allah nature." Indeed, Izutsu would probably say they cannot be called "angels" if they do not do so. The subject of angels would arise once again in his later years as main topics in his discussion of "the angelology of WORD" and "the angel aspect of WORD" in Ishiki to honshi1su.

'l'he first work by Toshihiko Izutsu after he returned froni Iran in 1979 was Isuramu seitan (1979; The birth of Isthm)!" Part One, the biography of Mulamniad, was a reworking of the older hook Maliosn-etto, which modified its "extravagantly figurative" expression. The version contained in his selected works (iqo) is also the newer one, which he further revised and enlarged. In 1989, however, Toshihiko Izutsu republished the original version of Mahornetto. 'The reason for doing so, he wrote, was "that, despite its many flaws, I have come to believe that there is, on the whole, an interesting quality and a special

• I • • I I I I • I • • 1

flavor in the original work, and only in the original work."

When he republished Shin p1 tetsugaku in 1978 and combined Arabia shisoshi and Arabia tetsugaku and published them as Isuraniu shisôshi ('975; History of Islamic thought) while he was still in Iran, he commented on the significance of their republication, saving that these were works lie had written as a young man and that they could only have been written at such a time. That does not mean, however, that he ventured to republish them in versions faithful to the original, as he did in the case of Mahometto. An overview of intellectual history and a biography of the Prophet are different genres, and yet the significance he placed on the republication of Mahometto is profound in the sense that it was a return to his starting point.

Reading Mahornetto calls to mind Hideo Kobayashi-, writings on Rimbaucl. Not because they are both works by young men in which they describe the God of their youth, but because they are candid snapshots of their authors' entrance into the other world. Moreover, like Kobayashi, Toshihiko Izutsu's biography of the Prophet and his other works of this period, rather thaii being scholarly monographs, contain an element of literary criticism, what Baudelaire called poetry on a higher level. That is not just my own impressionistic opinion. From a glance at the chronology of his writings, it is certainly possible to catch a glimpse of Thshihiko lzutsu the literary critic in the essays on Clan-del and the other works around the time of Roshia bun gaku (Russian

CHAPTER FOUR

A CONTEMPORARY ANI) 111F. RI(CRAPHY OF 111F. PROPHET

literature) and Roshiateki ningen (1953; Russian humanity) that were written just before or alter Makmefto.

The introduction to Mahometto cites a passage from the beginning of Goethe's Faust.

lhr naht euch wieder, schwankende Gestalten! Die fruh sich einst dem triiben Buck gezeigt. Versuch' ich wohi euch diesmal lest zu halten? FuhI' ich mein Hen noch jenem Wahn geneigt? lhr drangt euch zu! nun gut. so mögt ihr walten, \Vie ihr atis Dunst und Nebel urn mich stcigt Mein Busen fUhit sich jugendlich erschUttert Vom Zauberhauch, der euren Zug umwittert.

(Once more you near me. wavering apparitions That early showed before the turbid gaze. Will now I seek to grant you definition. My heart essay again the former daze? You press me! Well. I yield to your petition, As all around, you rise from mist and haze; What wafts about your train with magic glamor Is quickening ms' breast to youthful tremor.)

ZS

Faust was not a product of Goethe's imagination. He believed in the actual existence of the other world, that real life was located there. Had that not been the case, Goethe would not have needed to apply seven seals to the container in which he placed Faust after completing it. Izutsu also alludes to Goethe in Shinpi tetsugaku. Citing a passage from J.P. Eckermann's Gesprache mit Goethe 0836-1848; Goethes Conversations with J.P. Eckermann, 1850), "Ich denke mir die Erde mit ihrem Dunstkreise gleichnisweise als ein grosses lebendiges Wesen, das im ewigen Em- unci Ausatmen begriffen ist" (1 compare the earth and her atmosphere to a great living being, perpetually inhaling and exhaling), he calls Goethe "the classic example of someone who has experienced the World Soul.`9 Standing alone before the universe, detached from time and space, liberated from religion and from ideological

dogmas, the mind is suddenly connected to its life form," then led to the other world. When Izutsu thinks of Muhammad, he would probably say, he is always led before the gate to the other world that Goethe describes. Izutsu called Muhammad "the hero of the spiritual world." For Izutsu, ills the "spiritual world" that constitutes "reality."

Mahometto is a strange and wonderful work. What clearly remains ever time I read it is not the merchant who is transformed into the Prophet, but rather the vast Arabian landscape expectantly awaiting the Prophet's arrival. Perhaps that was the author's intention. Mat the thirty-eight-year-old Izutsu attempted to write, it would be fair to say. was not an objective biography of the Prophet, but rather the recollections of someone who had accompanied the author's hero. Izutsu does not deal with the "Prophet Muhammad"; instead he tries empir-icallv to follow the path that Mubamillad took to become a prophet and an apostle. As for the works on Mulammad written prior to this brief biography. he says, most of them are not "biographies" but merely legends"; his own objective, he declares, is demythologization. On the other hand, however, he does not conceal the passionate emotion welling up within him: "A depiction of Muhammad into which my own heart's blood doesn't directly How would be impossible for me to portray." he writes. But does an empirical mind that would elucidate history in the true sense nourish passion, he wonders. "For that reason," he writes, 1 will take the plunge and give myself over completely to the call of the chaotic and confused forms swarming in my breast," then goes on to say:

Forget that you are in the dush and dirt-filled streets of a major city proud of its culture and civilization and let your thoughts go where your imagination leads you thousands of miles beyond the sea to the desolate and lonely Arabian desert. The scorching sun burning relentlessly in the boundless sky, on earth the blistering rocky crags and the vast expanses of sand upon sand as far as the eye can see. It was in this strange and uncanny world that the Prophet Muhammad was born.

170

The Arabian landscape described in Mahometto is not the author's imagination. The writing tells its that. He would probably say that he

CHAPTER FOUR

A CONTEMPORARY AND THE BIOGRAPHY OF THE PROPHET

"saw" it. It is hard to believe he would have had any other reason than this for reviving the original v.ision. The recollections of what he saw and heard are also indelibly inscribed in the passages cited below. Read them, paving attention not just to their meaning but also to the style that he achieved here.

I-tall of this critical biography is devoted to a discussion of the Arab mind during the jcihilTvva before the appearance of Mulammad. Where he finds evidence for it is in the poems of this era. So frequently is poetry cited that this biography can be read as a poetry anthology or an essay on the poems of the jahiliyya period. "The only thing these pre-Islamic Arabs handed down to posterity," Izutsu says, "were the songs of the desert, which truly deserve to be called Arabic literature.""

Ali, enjoy this moment

For in the end death will come to the body. 32

In the background of this poem by Amr lhn Kuithum are a people who have lost sight of eternity. They were by nature realists who did not believe in life after death.

For them eternal life in a world other than this one was out of the question. Eternity, everlasting life in this world, had to be one enjoyed in the flesh. . . . Existence by its very nature is essentially ephemeral -having been mercilessly dashed against the cold iron wall of reality, people had to accept this. And if this world sadly is not to be relied on and human life but a brief sojourn, then it is a waste not to spend at least the short life we have been granted in intense pleasure. And SO People immersed themselves in immorality and debauchery and the search for transient intoxication.33

For those for whom only the phenomena] world is real, the natural conclusion is that the bonds of kinship are proof of their own existence. What confirmed this for the people of the desert, the Bedouin, was the tribe to which they belonged, in other words, blood ties. Tribal laws, traditions and customs determined individual behavior. If a member of one tribe met an untimely end at the hands of another tribe, for the remaining members revenge was "a sacred—quite literally a sacred—solemn duty." But Mubammad, "with a pitying smile for their haughtiness and arrogance, took no account whatsoever of the significance of blood ties and the preeminence of family lineage."" What he preached was just one thing: "A person's nobility does not derive from one's birth or family line; it is measured solely by the depth of one's pious fear of Cod."' Islam is, in fact, thoroughgoing in its insistence on equality in the sight of God. There was even a sect which took the position that someone who had been the object of discrimination in the past could become caliph, the leader of the theocracy, if the profundity of that person's faith were recognized.

Just as people arc absolutely dependent on God, time belongs to eternity. Eternity is real. Superiority of family lineage, which promises glory in this world, has no special significance whatsoever for the attainment of salvation. People exist in order to believe in and warship God, said Muhammad, preaching the absolute nature of piety. He rejected the existing values and customs and even the existing virtues. On the other hand. however, it was the pleasure-seeking realists, people oblivious to transcendence and eternity, those who obeyed the laws of their tribe rather than the laws of Cod. Izutsu writes, who were the verv ones that prepared the way for the coming of Mulammad. AL this time, "If [the Arab people] were not somehow saved, it would have been nothing less than spiritual ruin. The situation was truly becoming more and more urgent."

Above and beyond the relationships of need, hope, supplication and reliance, the reason people seek Cod is the result of the workings of oreksis, the instinctive desire to seek the Transcendent that Aristotle discussed. What Izutsu was looking for in the poems of the jahilTvva were the vestiges of oreksis. The urge that luimans have to return to their ontological origins triggered a chain reaction, Izutsu believed, that resonated and invited the Prophet. But what is desired does not necessarily appear in the desired form. The workings of Cod always exceed human expectations. Before they could obtain the salvation they sought. the Bedouin had to give up the blood ties they had previously considered most important.

At first, Muilanimad had no intention of founding a religion. 'i'hc Mubammad whom Izutsu describes is not the founder of a religion but an admonisher, a Spiritual revolutionary. "Mahoniet, who was sent as

CHAPTER FOUR

A CONTEMPORARY AND TilE 11IOGRAPI4Y OF I1IF PROM"

of religions that he is speaking of here is the scholar who, before regarding religion as an object of scientific study, holds it deeply and indelibly in mind as a "pressing problem of the soul."

According to Moroi's Tenri colleague, Tadamasa Fukava (19122007). when Gabriel Marcel visited rlènri and met Yoshinori Moroi, he was astonished to find someone in the Far East who had read his works so carefully. One wonders whether Moroi met Eliade when the latter visited Japan. Toshihiko Izutsu and Eliade met twice at the Eranos Conference. It took no time for the two of them to understand each other; it was as though they had been close friends for ten years, Izutsu wrote. Eliade came to Japan in August 1958 to attend the Ninth World Congress of the International Association for the History of Religions. Yoshinori Moroi's attendance at this conference can be confirmed from photographs taken at the time. Ichiro Hon (1910-1974), whose translations later introduced Eliade to Japan, had met him in Chicago the previous year, but Eliade's fame in Japan in those days was, of course, nothing like what it is today, lithe two of them had met, the encounter with Moroi would likely have left as deep all impression on Eliade as the one with 'Ibshihiko Izutsu did.

Shamanism is central theme for Toshihiko Izutsu that runs through his works from Shinpi tetsugaku (1949) to Ishiki to hons/,itsu (1983). The subtitle of his major English-language book, Sufism and Taoism (1983), is "A Comparative Study of Key Philosophical Concepts," but it might just as well have been subtitled "A Study of Oriental Shamanism." At the beginning of the section on Taoist thought in that work, Izutsu deals with the evidence for Lio-tzU the man and Chuang-tzO the man, i.e. for the historical reality of Li Er and Chuang Chou, relying on Shih Chi (Book of History) as well as records handed down by the Confucianists, but at a certain point, as if disavowing these efforts to verify their existence, he says that, as long as the writings attributed to "Lao-tzü" and "Chuang-tai" exist, whether or not they themselves existed as historical figures is only a secondary matter. The true subject is what Lao-tzü calls Tao; a person is only a channel for it. Insofar as the one who speaks is not a human being, but One who transcends human beings, the personal identity of these men is probably not a primary concern.

This insight truly conveys rlbshihik() Izutsu's intellectual outlook. Unlike Moroi, Izutsu does not make a sharp distinction between shamanism and mysticism. He lakes the attitude that a higher order of spirits is quite capable of transmitting a glimpse of the Transcendent. On this point, Yoshinori Moroi and loshihiko Izutsu do not agree. Indeed. Toshihiko Izutsu does not agree with anyone on this matter. As quoted earlier, his view that ancient Greece. while having a shamanistic spirituality, essentially tended toward moIlc)thcism, attests to the originality of Izutsu's experience of Greece.

"The mystical experience is not a human being's experience of God," Izutsu says in his studs' of St Bernard. "It is, rather, God's experience of himself." If Cod seeing God is regarded as the mystical experience, then the human being is somewhere in between, forced to see God with God's eyes and at the same time with his/her own human eyes. Properly speaking, this is beyond the power of human endurance. In Greek mythology, the human Scmele. who asked Zeus to show himself in his true form, lost her life. But this is also the highest favor that can be bestowed on a human being. In the nature of things. people cannot know the Iirgrund of their being through their own power alone, it is only at the instigation of the Transcendent that they are able to do so. The relation between Cod and human is asymmetric and irreversible.

"Urgrund" would become a key concept in Yoshinori Moroi's thought. The German prefix "Fir," meaning "primal," is affixed to the word "Crund" and used as a single word to emphasize our primordial nature. "On reflection, knowing this tlrgrund was not something that human beings are essentially capable of doing. Originally, it was something that was absolutely impossible for them to do.... The Creator knows the (Jrgrund of creatures. tirgrund is perhaps something that is made known only by being told or taught by the One who knows the origin of its formation. [People] are able to know [the truth of their tirgr. und] only by being informed of it."4 This passage is not a scholarly observation; it perhaps ought to be read as a profession of faith by Yoshinori Moroi, the student of Tenri-kyO. But inasmuch as scholarship for him was also a way of cultivating faith, there is probably no need to make a dichotomy between his existential positions as a scholar and as a believer.

CHAPTER FOUR

A CONTEMPORARY ANI) THE BIOGRAPHY OF THE PROPHET

this principle might well be said to have further strengthened the passion and the power of imagination that he invests in substantiating his hypotheses. Mystics often say that the present is joined to eternity; Morn, attempts to find the pathway to eternity in every passage, every word, of the texts.