엔네아데스

《엔네아데스》(그리스어: Ἐννεάδες)는 플로티노스가 남긴 54개의 논문을 제자 포르피리오스가 정리한 것이다. 포르피리오스는 이들 논문을 내용상 9개씩으로 정리하고 전체를 6권이 되게 편집하였다.

'엔네아데스'란 본시 '9'를 의미하는 그리스어 '엔네아스'의 복수(複數)이다. 따라서 각 권(卷)은 '엔네아스'라고 불리며 '엔네아데스'는 전체를 지칭한다. 다시 '6'이 '1'·'2'·'3'의 합이므로 전체가 제1-3권까지의 3권으로 되는 제1부와 제4-5의 2권으로 되는 제2부 및 제6권을 제3부로 하는 총3부로 구성되어 있다. 그리고 3부는 각각 플로티노스의 3원리(三原理)가 반영되도록 잘 편집되어 있다. 즉 제3부에 해당하는 제6권에는 <선한 것, 1인 것에 관하여> 등 '1자(一者)'에 관한 논문이 집록되어 있다.

아름다움[편집]

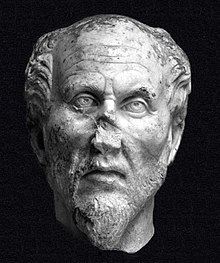

고대 후기 그리스 철학자 중 한 사람인 플로티노스에게 ‘아름다움(美)’이란 ‘선(善)’과 다르지 않았다. 다시 말해 아름다움을 추구하는 것이 존재의 자기실현으로서 의미가 있다는 것이다.

오늘날 아름다움에 대한 판단은 그 본질에 대한 논의를 망각한 채 점점 상대주의적인 것으로 굳어가고, 아예 아름다움에 대한 객관적 판단은 불가능한 것처럼 여겨지기까지 한다. 저자는 이 책을 통해 물질적인 아름다움의 기초가 되는 정신적인 아름다움에 관심을 기울이고, 나아가 그런 정신적인 모든 아름다움에 원천이 되는 아름다운인 '아름다움의 아름다움'을 알아내도록 노력해야 할 것을 제안한다.

오늘날 ‘아름다움’에 대한 판단은 실로 다양하게 이루어지고 있으며, 다양한 만큼 난해하다. 특히 인터넷 시대를 맞아 과거에 비해 더더욱 잦아지는 소위 ‘예술’과 ‘외설’의 시비 문제, 그리고 예술적 패러디와 저작권 침해의 법적 공방 등 아예 아름다움에 대한 객관적 판단은 불가능한 것처럼 여겨지기까지 한다. 원숭이의 장난이 썩 괜찮은 작품이 될 수 있다면, 도대체 예술은 무엇하러 존재하는가? 하나의 사물을 작품으로 만들어주는 게 ‘이론’이라면 예술가들은 대체 왜 존재하는가? 현대에 널리 유포된 상대주의적인 입장, 심지어 예술 자체의 순수성만을 고집해야 한다는 입장을 우리는 어느 선까지 수긍해야 할까? 더 이상 객관적인 미적 판단은 불가능한 것일까? 이 같은 맥락에서 그의 ‘아름다움에 관한 논의’는 분명 우리에게 생각할 거리를 제공한다.

'아름다운 것에 관해', '정신의 아름다움에 관해'는 ‘아름다움’을 주제로 한 그의 대표적인 작품이다. 이 두 작품을 읽어나갈 때 최소한 다음과 같은 점을 주목할 필요가 있다. 예컨대 그는 ‘아름다움’을 어떻게 정의하고 있는가? 그가 자신의 입으로 플라톤의 사상을 그대로 전달하고 해석하는 자임을 스스로 밝혔다 하더라도 미적 판단에 있어 그와 플라톤 사이에 어떤 차이가 있는가? 그는 물질적 복합체에 대한 미적 판단에는 한계가 있음을 지적한다. 플라톤과 아리스토텔레스가 채택했던 개념인 비례관계는 비록 아름다운 “형상”에 대한 다양한 표현의 하나이긴 하지만, 복합체가 아닌 정작 ‘순수한 것’, 나아가 ‘정신적인 존재’에 대한 미적 판단에는 도움이 되지 못한다는 것이다. 결국 물질적인 아름다움의 기초가 되는 정신적인 아름다움에 관심을 기울여야 바람직할 것이요, 나아가 그런 정신적인 모든 아름다움에 원천이 되는 아름다움, 곧 ‘아름다움(들)의 아름다움’을 알아내도록 노력해야 할 것이라고 제안한다.

사랑[편집]

사랑은 ‘아름다움’과 직결된 개념이다. 플라톤의 작품 『향연』의 주제가 사랑이다. 특히 ‘미의 여신’ 아프로디테의 탄생을 축하하는 연회 때, 제우스 신의 뜰 안에서 포로스와 페니아 사이에 태어난 에로스는 고대인들에게 오랫동안 사랑의 의미를 되새기고자 할 때마다 재고되었다. 그는 플라톤의 작품 『향연』과 『파이드로스』에 천착하여 다른 사상가들의 다양한 견해들을 집약하는 재치를 발휘한다. 나아가 저 천상의 ‘에로스’와 우리 곁에서 경험되는 사랑의 차이는 무엇인가? 그와 더불어 두 아프로디테의 모습은 실제 무엇을 의미하는가? 저 에로스는 신인가 아니면 정령인가? 우리에게 사랑은 무엇을 함의하는가? 하는 물음을 끊임없이 던진다. 즉 사랑은 언제든 선을 찾아 나설 만큼 선에 있어 전적으로 모자람이 없다. 그런 점에서 에로스가 포로스와 페니아 사이에서 태어났다고 말하는 것이고, 그런 한에서 부족함, 추구하는 노력, 로고스에 대한 기억이 영혼 안에 자리함으로써 영혼이 선을 지향하는 능력을 낳았다고 할 때, 이것이 바로 사랑이라는 것이다.

===

Enneads

| Part of a series on |

| Neoplatonism |

|---|

|

The Enneads (Greek: Ἐννεάδες), fully The Six Enneads, is the collection of writings of Plotinus, edited and compiled by his student Porphyry (c. AD 270). Plotinus was a student of Ammonius Saccas and they were founders of Neoplatonism. His work, through Augustine of Hippo, the Cappadocian Fathers, Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite and several subsequent Christian and Muslim thinkers, has greatly influenced Western and Near-Eastern thought.

Contents[edit]

Porphyry edited the writings of Plotinus in fifty-four treatises, which vary greatly in length and number of chapters, mostly because he split original texts and joined others together to match this very number. Then, he proceeded to set the fifty-four treatises in groups of nine (Greek. ennea) or Enneads. He also collected The Enneads into three volumes. The first volume contained the first three Enneads (I, II, III), the second volume has the Fourth (IV) and the Fifth (V) Enneads, and the last volume was devoted to the remaining Enneads. After correcting and naming each treatise, Porphyry wrote a biography of his master, Life of Plotinus, intended to be an Introduction to the Enneads.

Porphyry's edition does not follow the chronological order in which Enneads were written (see Chronological Listing below), but responds to a plan of study which leads the learner from subjects related to his own affairs to subjects concerning the uttermost principles of the universe.

Although not exclusively, Porphyry writes in chapters 24-26 of the Life of Plotinus that the First Ennead deals with human or ethical topics, the Second and Third Enneads are mostly devoted to cosmological subjects or physical reality. The Fourth concerns the Soul, the Fifth knowledge and intelligible reality, and finally the Sixth covers Being and what is above it, the One or first principle of all.

Citing the Enneads[edit]

Since the publishing of a modern critical edition of the Greek text by Paul Henry and Hans-Rudolf Schwyzer (Plotini Opera. 3 volumes. Paris-Bruxelles, 1951–1973; H-S1 or editio major text) and the revised one (Plotini Opera. 3 volumes. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1964–1984; referred to as the H-S2 or editio minor text) there is an academic convention of citing the Enneads by first mentioning the number of Ennead (usually in Romans from I to VI), the number of treatise within each Ennead (in arabics from 1 to 9), the number of chapter (in arabics also), and the line(s) in one of the mentioned editions. These numbers are divided by periods, commas, or blank spaces.

E.g. For Fourth Ennead (IV), treatise number seven (7), chapter two (2), lines one to five (1-5), we write:

- IV.7.2.1-5

E.g. The following three mean Third Ennead (III), treatise number five (5), chapter nine (9), line eight (8):

- III, 5, 9, 8

- 3,5,9,8

- III 5 9 8

It is important to remark that some translations or editions do not include the line numbers according to P. Henry and H.-R. Schwyzer's edition. In addition to this, the chronological order of the treatises is numbered between brackets or parentheses, and given below.

E.g. For the previously given:

- IV.7 (2).2.1-5 since treatise IV.7 was the second written by Plotinus.

- III, 5 [50], 9, 8 since III.5 was the fiftieth written by Plotinus.

Table of contents[edit]

The names of treatises may differ according to translation. The numbers in square brackets before the individual works refer to the chronological order they were written according to Porphyry's Life of Plotinus.

First Ennead[edit]

- I.1 [53] - "What is the Living Being and What is Man?"

- I.2 [19] - "On Virtue"

- I.3 [20] - "On Dialectic [The Upward Way]."

- I.4 [46] - "On True Happiness (Well Being)"

- I.5 [36] - "On Whether Happiness (Well Being) Increases with Time."

- I.6 [1] - "On Beauty"

- I.7 [54] - "On the Primal Good and Secondary Forms of Good [Otherwise, 'On Happiness']"

- I.8 [51] - "On the Nature and Source of Evil"

- I.9 [16] - "On Dismissal"

Second Ennead[edit]

- II.1 [40] - "On Heaven"

- II.2 [14] - "On the Movement of Heaven"

- II.3 [52] - "Whether the Stars are Causes"

- II.4 [12] - "On Matter"

- II.5 [25] - "On Potentiality and Actuality"

- II.6 [17] - "On Quality or on Substance"

- II.7 [37] - "On Complete Transfusion"

- II.8 [35] - "On Sight or on how Distant Objects Appear Small"

- II.9 [33] - "Against Those That Affirm The Creator of the Kosmos and The Kosmos Itself to be Evil" [generally quoted as "Against the Gnostics"]

Third Ennead[edit]

- III.1 [3] - "On Fate"

- III.2 [47] - "On Providence (1)."

- III.3 [48] - "On Providence (2)."

- III.4 [15] - "On our Allotted Guardian Spirit"

- III.5 [50] - "On Love"

- III.6 [26] - "On the Impassivity of the Unembodied"

- III.7 [45] - "On Eternity and Time"

- III.8 [30] - "On Nature, Contemplation and the One"

- III.9 [13] - "Detached Considerations"

Fourth Ennead[edit]

- IV.1 [21] - "On the Essence of the Soul (1)"

- IV.2 [4] - "On the Essence of the Soul (2)"

- IV.3 [27] - "On Problems of the Soul (1)"

- IV.4 [28] - "On Problems of the Soul (2)"

- IV.5 [29] - "On Problems of the Soul (3)” [Also known as, "On Sight"].

- IV.6 [41] - "On Sense-Perception and Memory"

- IV.7 [2] - "On the Immortality of the Soul"

- IV.8 [6] - "On the Soul's Descent into Body"

- IV.9 [8] - "Are All Souls One"

Fifth Ennead[edit]

- V.1 [10] - "On the Three Primary Hypostases"

- V.2 [11] - "On the Origin and Order of the Beings following after the First"

- V.3 [49] - "On the Knowing Hypostases and That Which is Beyond"

- V.4 [7] - "How That Which is After the First comes from the First, and on the One."

- V.5 [32] - "That the Intellectual Beings are not Outside the Intellect, and on the Good"

- V.6 [24] - "On the Fact that That Which is Beyond Being Does not Think, and on What is the Primary and the Secondary Thinking Principle"

- V.7 [18] - "On whether There are Ideas of Particular Beings"

- V.8 [31] - "On the Intellectual Beauty"

- V.9 [5] - "On Intellect, the Forms, and Being"

Sixth Ennead[edit]

- VI.1 [42] - "On the Kinds of Being (1)"

- VI.2 [43] - "On the Kinds of Being (2)"

- VI.3 [44] - "On the Kinds of Being (3)"

- VI.4 [22] - "On the Presence of Being, One and the Same, Everywhere as a Whole (1)"

- VI.5 [23] - "On the Presence of Being, One and the Same, Everywhere as a Whole (2)"

- VI.6 [34] - "On Numbers"

- VI.7 [38] - "How the Multiplicity of Forms Came Into Being: and on the Good"

- VI.8 [39] - "On Free Will and the Will of the One"

- VI.9 [9] - "On the Good, or the One"

Plotinus's Original Chronological Order[edit]

The chronological listing is given by Porphyry (Life of Plotinus 4–6). The first 21 treatises (through IV.1) had already been written when Porphyry met Plotinus, so they were not necessarily written in the order shown.

- I.6, IV.7, III.1, IV.2, V.9, IV.8, V.4, IV.9, VI.9

- V.1, V.2, II.4, III.9, II.2, III.4, I.9, II.6, V.7

- I.2, I.3, IV.1, VI.4, VI.5, V.6, II.5, III.6, IV.3

- IV.4, IV.5, III.8, V.8, V.5, II.9, VI.6, II.8, I.5

- II.7, VI.7, VI.8, II.1, IV.6, VI.1, VI.2, VI.3, III.7

- I.4, III.2, III.3, V.3, III.5, I.8, II.3, I.1, I.7

In table format, the chronological order of Porphyry corresponding each of the Ennead treatises is:[1]

| Chronological order | Ennead treatise |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1.6 |

| 2 | 4.7 |

| 3 | 3.1 |

| 4 | 4.2 |

| 5 | 5.9 |

| 6 | 4.8 |

| 7 | 5.4 |

| 8 | 4.9 |

| 9 | 6.9 |

| 10 | 5.1 |

| 11 | 5.2 |

| 12 | 2.4 |

| 13 | 3.9 |

| 14 | 2.2 |

| 15 | 3.4 |

| 16 | 1.9 |

| 17 | 2.6 |

| 18 | 5.7 |

| 19 | 1.2 |

| 20 | 1.3 |

| 21 | 4.1 |

| 22 | 6.4 |

| 23 | 6.5 |

| 24 | 5.6 |

| 25 | 2.5 |

| 26 | 3.6 |

| 27 | 4.3 |

| 28 | 4.4 |

| 29 | 4.5 |

| 30 | 3.8 |

| 31 | 5.8 |

| 32 | 5.5 |

| 33 | 2.9 |

| 34 | 6.6 |

| 35 | 2.8 |

| 36 | 1.5 |

| 37 | 2.7 |

| 38 | 6.7 |

| 39 | 6.8 |

| 40 | 2.1 |

| 41 | 4.6 |

| 42 | 6.1 |

| 43 | 6.2 |

| 44 | 6.3 |

| 45 | 3.7 |

| 46 | 1.4 |

| 47 | 3.2 |

| 48 | 3.3 |

| 49 | 5.3 |

| 50 | 3.5 |

| 51 | 1.8 |

| 52 | 2.3 |

| 53 | 1.1 |

| 54 | 1.7 |

Note on the Plotiniana Arabica or Arabic Plotinus[edit]

After the fall of Western Roman Empire and during the period of the Byzantine Empire, the authorship of some Plotinus' texts became clouded. Many passages of Enneads IV-VI, now known as Plotiniana Arabica, circulated among Islamic scholars (as Al-Kindi, Al-Farabi and Avicenna) under the name The Theology of Aristotle or quoted as "Sayings of an old [wise] man". The writings had a significant effect on Islamic philosophy, due to Islamic interest in Aristotle. A Latin version of the so-called Theology appeared in Europe in 1519. (Cf. O'Meara, An Introduction to the Enneads. Oxford: 1995, 111ff.)

Bibliography[edit]

- Critical editions of the Greek text

- Bréhier, Émile, Plotin: Ennéades (with French translation), Collection Budé, 1924–1938.

- Henry, Paul, and Hans-Rudolf Schwyzer. Plotini Opera. (Editio maior in 3 vols. including English translation of Plotiniana Arabica or The Theology of Aristotle) Bruxelles and Paris: Museum Lessianum, 1951–1973.

- Henry, Paul, and Hans-Rudolf Schwyzer. Plotini Opera. (Editio minor in 3 vols.) Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1964–1982.

- Complete English translations

- Taylor, Thomas, Collected Writings of Plotinus, Frome, Prometheus Trust, 1994. ISBN 1-898910-02-2 (contains approximately half of the Enneads)

- Guthrie, Kenneth Sylvan, Plotinos, Complete Works in 4 vols., Comparative Literature Press, 1918.

- Plotinus. The Enneads (translated by Stephen MacKenna), London, Medici Society, 1917–1930 (an online version is available at Sacred Texts); 2nd edition, B. S. Page (ed.), 1956.

- Armstrong, A. H., Plotinus. Enneads (with Greek text), Loeb Classical Library, 7 vol., 1966–1988.

- Gerson, Lloyd P. (ed.); George Boys-Stones, John M. Dillon, Lloyd P. Gerson, R.A. King, Andrew Smith and James Wilberding (trs.). The Enneads. Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Commentaries

- The Enneads of Plotinus Series. Edited by John M. Dillon and Andrew Smith. Parmenides Publishing. 2012–Ongoing.

- Atkinson, Michael. Plotinus' Ennead V.1: On the Three Principal Hypostases Oxford: OUP, 1983.

- Bussanich, John. The One and Its Relation to Intellect (Translation and commentary of selected treatises). Leiden: Brill, 1988.

- Fleet, Barrie. Plotinus Ennead III.6. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995.

- Kalligas, Paul. The Enneads of Plotinus: A Commentary (Volume 1: Enneads I–III). Princeton University Press, 2014.

- Lexicons and bibliographies

- Sleeman, J. H. and Pollet, G. Lexikon Plotinianum. Leiden: Brill, 1980.

- Dufour, R. Plotinus. A Bibliography: 1950-2000. Leiden: Brill, 2002.

- Radice. R. and Bombacigno, R. Lexicon II: Plotinus. (Includes a CD containing the entire Greek text) Milan: Biblia, 2004.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Gerson, Lloyd P., ed. (2018). The Enneads. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-00177-0. OCLC 993492241.

External links[edit]

Works related to Enneads at Wikisource

Works related to Enneads at Wikisource- The Six Enneads (complete Stephen MacKenna and B. S. Page translation) in PDF, HTML, Microsoft Word, Plain Text, Theological Markup Language (XML), and 'Palm Doc' versions.

- The Six Enneads – Mackenna and Page translation divided into six sections in HTML.

- The Enneads, Greek text page scans of Kirchhoff's edition.

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Plotinus

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Plotinus

- Plotinian Bibliography 2001- by Richard Dufour (French and English versions), continues his research presented in Plotinus: a Bibliography 1950-2000, referred above.

- Links to Enneads, treatises, and chapters in English, Greek, and French for quick reference.

- Ἐννεάδες – The Henry and Schwyzer 1951 edition (Greek text) at Bibliotheca Augustiana.

Enneads public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Enneads public domain audiobook at LibriVox- Enneads – Alternate version of the LibriVox audiobook with Sections following the Translator Kenneth Sylvan Guthrie's Chronological Organization of the Books.