Religion in Fiji

This article includes a list of general references, but it remains largely unverified because it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (May 2010) |

| Religion by country |

|---|

Religiously, Fiji is a mixed society with most people being Christian (64.4% of the population), with a sizable Hindu (27.9%) and Muslim (6.3%) minority, according to the 2007 census.[2] Religion tends to split along ethnic lines with most Indigenous Fijians being Christian and most Indo-Fijians being either Hindu or Muslim.[3]

Aboriginal Fijian religion could be classified in modern terms as forms of animism or shamanism, traditions utilizing various systems of divination which strongly affected every aspect of life. Fiji was Christianized in the 19th century. Today there are various Christian denominations in Fiji, the largest being the Methodist church. Hinduism and Islam arrived with the importation of large numbers of people from South Asia, most of them indentured, in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Fiji has many public holidays as it acknowledges the special days held by the various belief systems, such as Easter and Christmas for the Christians, Diwali for the Hindus and the Eid al-Adha for the Muslims.[4]

History[edit]

Fijian religion prior to the 19th century included various forms of animism and divination. Contact from the early 19th century with European Christian missionaries, especially of the Methodist denomination, saw conversion of dominant chiefs such as Octavia and thus also the people they controlled. Cession of the islands to Great Britain in 1874 saw great change in all aspects of life including religious practice. Christianity became the dominant faith. Hinduism, Sikhism and Islam were introduced as minority migrant communities came to work in Fiji. Fiji's modern religious community is thus:

Demographics[edit]

| Religion | 1996 | 1996 % | 2007 | 2007 % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anglican | 6325 | 0.8% | 6319 | 0.8% |

| Assembly of God | 31072 | 4.0% | 47791 | 5.7% |

| Catholic | 69320 | 8.9% | 76465 | 9.1% |

| Methodist | 280628 | 36.2% | 289990 | 34.6% |

| Seventh-day Adventist | 22187 | 2.9% | 32316 | 3.9% |

| Other Christians | 39950 | 5.2% | 86672 | 10.4% |

| Hindu | 261097 | 33.7% | 233414 | 27.9% |

| Sikh | 3067 | 0.4% | 2540 | 0.3% |

| Muslim | 54323 | 7.0% | 52505 | 6.3% |

| Other Religion | 1967 | 0.3% | 2181 | 0.3% |

| No Religion | 5132 | 0.7% | 7078 | 0.8% |

| Total Christian | 449482 | 58.0% | 539553 | 64.4% |

| Total | 775068 | 100% | 837271 | 100% |

| Religion | Indigenous Fijian | Indo-Fijian | Others | TOTAL | ||||

| 393,575 | % | 338,818 | % | 42,684 | % | 775,077 | % | |

| Methodist | 261,972 | 66.6 | 5,432 | 1.6 | 13,224 | 31.0 | 280,628 | 36.2 |

| Roman Catholic | 52,163 | 13.3 | 3,520 | 1.0 | 13,637 | 31.9 | 69,320 | 8.9 |

| Assemblies of God | 24,717 | 6.2 | 4,620 | 1.4 | 1,735 | 4.1 | 31,072 | 4.0 |

| Seventh-day Adventist | 19,896 | 5.1 | 572 | 0.2 | 1,719 | 4.0 | 22,187 | 2.9 |

| Anglican | 2,508 | 0.6 | 1,208 | 0.4 | 2,609 | 6.2 | 6,325 | 0.8 |

| Jehovah's Witness | 4,815 | 1.2 | 486 | 0.1 | 801 | 1.9 | 6,102 | 0.8 |

| CMF (Every Home) | 5,149 | 1.3 | 269 | 0.1 | 255 | 0.6 | 5,673 | 0.7 |

| Latter Day Saints | 2,253 | 0.6 | 633 | 0.2 | 589 | 1.4 | 3,475 | 0.4 |

| Apostolic | 2,237 | 0.6 | 250 | 0.1 | 106 | 0.2 | 2,593 | 0.3 |

| Gospel | 618 | 0.2 | 514 | 0.2 | 222 | 0.5 | 1,354 | 0.2 |

| Baptist | 695 | 0.2 | 382 | 0.1 | 219 | 0.5 | 1,296 | 0.2 |

| Salvation Army | 628 | 0.2 | 251 | 0.1 | 110 | 0.3 | 989 | 0.1 |

| Presbyterian | 105 | 0.0 | 90 | 0.0 | 188 | 0.4 | 383 | 0.0 |

| Other Christian | 12,624 | 3.2 | 2,492 | 0.7 | 2,969 | 7.0 | 18,085 | 2.3 |

| All Christians | 390,380 | 99.2 | 20,719 | 6.1 | 38,383 | 89.9 | 449,482 | 58.0 |

| Sanātanī | 551 | 0.1 | 193,061 | 57.0 | 315 | 0.7 | 193,927 | 25.0 |

| Arya Samaj | 44 | 0.0 | 9,493 | 2.8 | 27 | 0.1 | 9,564 | 1.2 |

| Kabir Panthi | 43 | 0.0 | 73 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.0 | 118 | 0.0 |

| Sai Baba | 7 | 0.0 | 52 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.0 | 60 | 0.0 |

| Other Hindu | 219 | 0.1 | 57,096 | 16.9 | 113 | 0.3 | 57,428 | 7.4 |

| All Hindus | 864 | 0.2 | 259,775 | 76.7 | 458 | 1.1 | 261,097 | 33.7 |

| Sunni Islam | 175 | 0.0 | 32,082 | 9.5 | 94 | 0.2 | 32,351 | 4.2 |

| Ahmadiyya | 18 | 0.0 | 1,944 | 0.6 | 14 | 0.0 | 1,976 | 0.3 |

| Other Muslim | 131 | 0.0 | 19,727 | 5.8 | 138 | 0.3 | 19,996 | 2.6 |

| All Muslims | 324 | 0.1 | 53,753 | 15.9 | 246 | 0.6 | 54,323 | 7.0 |

| Sikh | 0 | 0.0 | 3,076 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 3,067 | 0.4 |

| Baháʼí Faith | 389 | 0.1 | 25 | 0.0 | 149 | 0.3 | 563 | 0.1 |

| Confucianism | 8 | 0.0 | 21 | 0.0 | 336 | 0.8 | 365 | 0.0 |

| Other religions | 61 | 0.0 | 314 | 0.1 | 664 | 1.6 | 1,039 | 0.1 |

| No religion† | 1549 | 0.4 | 1,135 | 0.3 | 2,448 | 5.7 | 5,132 | 0.7 |

† Includes atheists and agnostics. Source: "Population by Religion and by Race - 1996 Census of Population". Fiji Islands Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original on 16 September 2008. Retrieved 5 August 2017.,

Law[edit]

Fiji had traditional law prior to becoming a colony. After cession, laws that governed Britain were also applied to its colonies and religion developed under the Westminster system. Freedom of religion and conscience has been constitutionally protected in Fiji since the country gained independence in 1970. In 1997, a new constitution was drawn up. It stated

but also guaranteed every person

The 1997 Constitution was suspended in 2009 and replaced in 2013. This constitution states in chapter 1:[6]

The 2013 Constitution also explicitly allows people to swear an oath or to make an affirmation when legally necessary.

Ancient religion[edit]

This article contains too many or overly lengthy quotations for an encyclopedic entry. (April 2008) |

The term ancient religion in this article refers to the religious beliefs and practices in Fiji prior to it becoming a Colony.

Gods, temples and magic[edit]

Fijian religion, myth, and legend were closely linked and in the centuries before the cession of 1874, it was considered part of everyday life. Of the traditional religion in Fiji, Basil Thomson (1908:111) writes:

Myth was very much reality in the years preceding and following cession. For example, in Taveuni their god, Kalou Vu(root god), is named Dakuwaqa (Back boat). In Levuka and Kadavu Islands he is known as Daucina (Expert Light) due to the phosphorescence he caused in the sea as he passed. Daucina, however, has a different connotation as a Kalou yalo (deified ancestors) in other parts of Fiji.

Dakuwaqa took the form of a great shark and lived on Benau Island, opposite Somosomo Strait. He was highly respected by the people of Cakaudrove and Natewa as the god of seafaring and fishing communities, but also the patron of adulterers and philanderers. In the book "Pacific Irishman", the Anglican priest Charles William Whonsbon-Ashton records in Chapter 1, "Creation":[8]

As late as 1957, R.A Derrick (1957:13) states:

The Gods and their temples

Traditionally Fijian religion had a hierarchy of gods called "Kalou" or sometimes in the western dialect "Nanitu". In 1854 an early Methodist missionary, Rev. Joseph Waterhouse stated:

The Fijian gods (Kalou-Vu, Kalou-Yalo and numerous lesser spirits) were generally not made into any form of idol or material form for worship apart from some small objects used in ceremony and divination. However, it was more prevalent that certain places or objects like rocks, bamboo clumps, giant trees such as Baka or Ivi trees, caves, isolated sections of the forest, dangerous paths and passages through the reef were considered sacred and home to a particular Kalou-Vu or Kalou-Yalo and were thus treated with respect and a sense of awe and fear, or "Rere", as it was believed they could cause sickness, death, or punish disobedience. Others would provide protection. Thomas Williams and James Calvert in their book "Fiji and the Fijians" writes:

The main gods were honoured in the Bure Kalou or temple. Each village had its Bure Kalou and its priest (Bete). Villages that played a pivotal role in the affairs of the Vanua had several Bure Kalou. The Bure Kalou was constructed on a high raised rock foundation that resembled a rough pyramid base and stood out from other bures because of its high roof, which formed an elongated pyramid shape. Inside, a strip of white masi cloth hung from the top rafters to the floor as conduit of the god. More permanent offerings hung around the wall inside. Outside of the Bure Kalou, plants with pleasant aromas were grown which facilitated spiritual contact and meditation. Many of the gods were not celebrated for their sympathetic ear to man or their loving natures, rather they were beings of supernatural strength and abilities that had little concern for the affairs of man. Peter France (1966:109 and 113) notes:

First and foremost among the Kalou-vu was Degei, who was a god of Rakiraki but was known throughout most of the Fiji Group of islands except for the eastern islands of the Lau group. He was believed to be the origin of all tribes within Fiji and his power was superior to most, if not all, the other gods. He was often depicted as a snake, or as half snake and half stone. R.A Derrick (1957:11) says:

Other gods recognized throughout the Fiji group were: Ravuyalo, Rakola, and Ratumaibulu. Rokola was the son of Degei and was the patron of carpenters and canoe-builders, while Ratumaibulu assured the success of garden crops. Ravuyalo would stand watch on the path followed by departed spirits: he would look to catch them off guard and club them. His purpose was to obstruct their journey to the afterlife (Bulu).

Aspects and practices of the old religion[edit]

Consulting the gods

The different gods were consulted regularly on all manner of things from war to farming to forgiveness. The Bete (Priest) acted as a mediator between the people and the various Gods. R.A Derrick (1957:10 and 12) notes:

Rev. Joseph Waterhouse (1854:404) reports on the types of worship offered to the gods:

Laura Thompson (1940:112) speaking of the situation in Southern Lau states with regard to the Bete:

Rev. Joseph Waterhouse (1854:404/405) notes:

Witchcraft

Consulting the spirit world and using them to influence daily affairs were part of the Fiji religion. Using various specially decorated natural objects like a conch shell bound in coconut fibre rope or war club, it was a form of divination and was not only in the realm of priests. It was referred to as "Draunikau" in the Bauan vernacular and the practice was viewed as suspicious, forcing the practicers to do it stealthily. R.A Derrick (1957:10 and 15) writes:

A.M Hocart (1929:172) claims:

Dreaming

Dreams were also viewed as a means by which spirits and supernatural forces would communicate with the living and communicate special messages and knowledge. A dream where close relatives were seen conveying a message was termed "Kaukaumata" and was an omen warning of an approaching event that may have a negative impact on the dreamer's life. R.A Derrick, 1957:15-16:

Bert O. States in his book Dreaming and Story Telling states:

In some instances, there was also a person whose sole purpose was to interpret dreams. He or she was referred to as the "Dautadra", or the "dream expert". Martha Kaplan in her book Neither Cargo Nor Cult: Ritual Politics and the Colonial Imagination in Fiji notes:

Mana

"Mana" could be loosely translated as meaning magic or power or prestige, but it is better explained by anthropologist Laura Thompson (1940:109) when she writes:

Ana I. González in her web article "Oceania Project Fiji" writes:

In modern Fiji, while the term is still used in a traditional sense, it has a more generalized use and with the introduction of the Fijian Bible it is used to describe miracles. The term Mana, when used in ceremonial speech, can be interpreted as "it is true and has come to pass."

Afterlife

At death it is believed that the spirits of the dead would set off on a journey to Bulu, which is the home of the dead sometimes described as a paradise. Immediately after death the spirit of the recently departed is believed to remain around the house for four days and after such time it then goes to a jumping off point (a cliff, a tree, or a rock on the beach). At that point the spirit will begin their journey to the land of spirits (Vanua Ni Yalo). The spirit's journey would be a dangerous one because the god Ravuyalo would try to obstruct and hinder it on its travels to Vanua Ni Yalo. Anthropologist Laura Thompson (1940:115) writes:

Myth and legend[edit]

The Fijian race origins have many different lines passed down through oral traditional story or in relics of songs and dance, the most practical is found oral history. In myth it is accepted by most Fijians that their origins are found through the Kalou Vu Degei. An alternative tale from times past was published in the first part of the 19th century by Ms. Ann Tyson Harvey. This tells of Lutunasobasoba, supposedly a great ancestral chief and a brother of Degei II, whose people came to settle Fiji. The third story of Fijian origin is muddled in the two stories, but can be found in a local article referred to as the: "NAMATA", or the face. There are variations of this story; some versions state three migrations, some exclude Lutunasobasoba and have only Degei, but they have common themes.

In the writings of Ms. Ann Tyson Harvey (1969) in her paper "The Fijian Wanderers" she writes of Tura, who was a tribal chieftain in a time which pre-dates the era of the great pyramids. He lived near what is known as Thebes in Egypt. Legend speaks that his tribe journeyed to South Africa and settled on Lake Tanganyika in Tanzania, where Tura then Married a Tanzanian woman and then with his tribes, for various reasons, traveled ocean-ward out past Madagascar, through the Asian islands, ending their journey in Fiji; by this time Tura had died and his son Lutunasobasoba was leader. During a storm in the waters of the Mamanuca Island Group, he lost the chest of Mana, or more practically put, he lost the chest containing Fiji’s ancestors' written history before Fiji, including the written language.

Tired, old, sick, and weary, Lutunasobasoba set foot at Veiseisei and from there the early Fijians settled Fiji and his children were Adi Buisavuli, whose tribe was Bureta, Rokomautu whose tribe was Verata, Malasiga whose tribe was Burebasaga, Tui Nayavu whose tribe was Batiki, and Daunisai whose tribe was Kabara. It is believed in this mythology that his children gave rise to all the chiefly lines.

However, it is said that smoke was already rising before Lutunasobasoba set foot on Viti Levu. Villagers of the Province of Ra say that he was a trouble maker and was banished from Nakauvadra along with his people; it's been rumored the story was a fabrication of early missionaries. It is also believed there were three migrations, one led by Lutunasobasoba, one by Degei, and another by Ratu,traditionally known to reside in Vereta, along with numerous regional tales within Fiji that are not covered here and still celebrated and spoken of in story, song and dance.

These history have an important role in ceremony and social polity, as they are an integral part of various tribes' history and origins. They are often interconnected between one tribe and another across Fiji, such as the Fire walkers of Beqa and the Red prawns of Vatulele, to mention but a few. Also, each chiefly title has its own story of origin, like the Tui Lawa or Ocean Chieftain of Malolo and his staff of power and the Gonesau of Ra who was the blessed child of a Fijian Kalou yalo. The list goes on, but each, at some turn, find a common point of origin or link to the other.

Religion in modern Fiji[edit]

The term "Modern Fiji" in this article means Fiji after cession to Great Britain.

Christianity in Fiji[edit]

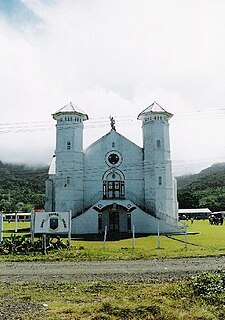

Christianity came to Fiji via Tonga, who were more receptive to the European visitors. As Tongan influence grew in the Lau Group of Fiji, so did Christianity under the Tongan Prince Enele Ma'afu. Its advancement was solidified further by the conversion of the emerging Dominant chieftain of Bau, Seru Epenisa Cakobau. The cession of 1874 saw a more dominant role within Fijian society as the old religion was gradually replaced by the new Christian faith. Bure Kalou were torn down and in their place churches were erected. Most influential were the Methodist denomination, which is the majority today, but other denominations such as Catholicism and Anglicanism, amongst other offshoots such as Baptists, Pentecostal and others, are a part of current Fijian religion. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was established in Fiji in the 1950s and currently reports 50 congregations, a technical college, and a Temple.[10] There are over 200 Orthodox Cristians, with 4 churches and one monastery.

Hinduism in Fiji[edit]

According to the 2007 census, Hindus form the second largest religious group in Fiji, comprising 27% of the population.[11] Hinduism in varying forms was the first of the Eastern religions to enter Fiji, with the introduction of the indentured labourers brought by the British authorities from India.

Islam in Fiji[edit]

Muslims in the country are mainly part of the Indo-Fijian community, they form about 6.3 percent of the total population (62,534). The Ba province in Fiji has more than 20,000 Muslims and is the most Muslim dominated area in Fiji.

Other religions in Fiji[edit]

Sikhism is also present among the Indo-Fijian population.

Fiji's old religion[edit]

While much of the old religion is now considered not much more than myth, some aspects of witchcraft and the like are still practiced in private, and many of the old deities are still acknowledged, but avoided, as Christianity is followed by the majority of indigenous Fijians.

Fiji religion in society and politics[edit]

The constitution of Fiji establishes the freedom of religion and defines the country as a secular state, but also provides that the government may override these laws for reasons of public safety, order, morality, health, or nuisance, as well as to protect the freedom of others. Discrimination on religious grounds is outlawed, and incitement of hatred against religious groups is a criminal offense. The constitution further states that religious belief may not be used as an excuse for disobeying the law, and formally limits proselytization on government property and at official events.[12]

Religious organizations must register with the government through a trustee in order to be able to hold property and to be granted tax-exempt status.[12]

Religious groups may run schools, but all religious courses or prayer sessions must be optional for students and teachers. Schools may profess a religious or ethnic character, but must remain open to all students.[12]

Religion, ethnicity, and politics are closely linked in Fiji; government officials have criticized religious groups for their support of opposition parties. In 2017, the Republic of Fiji Military Forces issued a press release stating that Methodist leaders were advocating for the country to become "a Christian nation" and that this could cause societal unrest. Following the press release, Methodist leaders distanced themselves from their previous statements, and other religious leaders also affirmed the nonpolitical nature of their religious movements.[13]

Many Hindus of Fiji emigrated to other countries.[14] Several Hindu temples were burned, believed to be arson attacks, for example, the Kendrit Shiri Sanatan Dharam Shiv Temple.[15][16] While Hindus face less persecution than before, a Hindu temple was vandalized in 2017. Later that year, following an online post by an Indian Muslim cleric visiting the country, a significant amount of anti-Muslim discourse was recorded on Fijian Facebook pages, causing controversy.[12]

Military-church relations[edit]

The Military of Fiji has always had a close relationship to Fiji's churches, particularly the Methodist Church, to which some two-thirds of Indigenous Fijians belong.

See also[edit]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ "Population by Religion and Province of Enumeration". 2007 Census of Population. Fiji Bureau of Statistics. June 2012. Archived from the original on 9 September 2015. Retrieved 7 November 2015. - Percentages are derived from total population figures provided in the source

- ^ a b "Religion - Fiji Bureau of Statistics". www.statsfiji.gov.fj. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ "International Religious Freedom Report for 2015". www.state.gov. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ "Fiji Government Online Portal - 2017 FIJI PUBLIC HOLIDAYS". www.fiji.gov.fj. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ "Fiji: The Constitution of Fiji 1997". www.wipo.int. Retrieved 8 June 2018. Section 35(1),(2)

- ^ "Fiji: Constitution of the Republic of Fiji 2013". www.wipo.int. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ "A Sleeping Buri, Built at Vewa, For the favourite little son of Namosemalua, Feejee" (PDF). The Wesleyan Juvenile Offering: A Miscellany of Missionary Information for Young Persons. Wesleyan Missionary Society. IX: 108. October 1852. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ^ Whonsbon-Aston, Charles William (8 August 1970). "1". Pacific Irishman: William Floyd inaugural memorial lecture. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ "Wesleyan Chapel, Naivuki, Vanua-Levu, Feejee". The Wesleyan Juvenile Offering: A Miscellany of Missionary Information for Young Persons. Wesleyan Missionary Society. X: 96. September 1853. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ "Religion – Fiji Statistical Profile". Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- ^ "International Religious Freedom Report Fiji" (PDF).

- ^ a b c d International Religious Freedom Report 2017 § Fiji US Department of State, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor.

- ^ International Religious Freedom Report 2017 § Fiji US Department of State, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor.

- ^ Sussana Trnka (2002), Foreigners at Home: Discourses of Difference, Fiji Indians and the Looting of May 19, Pacific Studies, Vol. 25, No. 4, pp. 69-90

- ^ "Another Arson attack on Fiji's Hindu Temples", ABC Radio Australia, 17 October 2008

- ^ "Time to speak up", Fiji Times, 17 October 2008

References[edit]

- Fiji and the Fijians, by Thomas Williams and James Calvert, chapter 7 (reference to Fijian old religion Myth and legend, their intertwining nature, and also to the emergence of Christianity.) page 248-249 (has detailed reference to Dranikau as Fijian witchcraft and details of the practice.) page 229 (has reference to the Dautadra or professional dreamer).

- Early Sociology of Religion, by Turner B. S. Staff, pages 218-219. (Details on Fijian religion and mythology.)

- "The Waimaro carved human figures - carvings from cachalot whale teeth in Fiji", The Journal of Pacific History, Sept 1997, by Aubrey L. Parke. (Discusses many aspects of Fiji's old religion.)

- A Feejeean and English Dictionary: With Examples of Common and Peculiar Modes of Expression, by David Hazlewood. (Details on Fijian deities, provides detailed definitions.)

- The Cyclopedia of Fiji: A Complete Historical and Commercial Review of Fiji, published 1984, R. McMillan, Original from the University of Michigan, Digitized Apr 3, 2007. (Reference to Degei, amongst other details of religion in Fiji.)

- The Journal of the Polynesian Society, by Polynesian Society (N.Z.), published 1967 (Reference to Degei.)

- Memoirs, by Polynesian Society (N.Z.), published 1945, Indian Botanical Society. (Reference to Degei and also Lutunasobasoba and aspects of Fijian religion.)

- The Islanders of the Pacific: Or, The Children of the Sun, by Thomas Reginald St. Johnston, published 1921, T.F. Unwin Ltd, pages 64, 70 and 161. (Details of Ratumaibulu and his role as a Fijian deity, also other details on Fijian deities or Kalou.)

- Vah-ta-ah, the Feejeean princess, by Joseph Waterhouse (Details on Fijian religion and deities of the old religion, and details of early Christianity and its missionaries.)

- Oceania, page 110, by University of Sydney, Australian National Research Council, 1930. (Details on Lutunasobasoba.)

- Young People and the Environment: An Asia-Pacific Perspective, page 131, by John Fien, David Yencken, and Helen Sykes. (Reference to Lutunasobasoba.)

- History of the Pacific Islands: Passage through Tropical Time, by Deryck Scarr, published by Routledge. (Reference to Fijian religion and mythology, details on various deities and religious practices and beliefs of pre-Christian Fiji.)

- The Fijians: A Study of the Decay of Custom, by Basil Thomson, published 1908 by W. Heinemann. (Details on Fijian legend and mythology, details on Lutunasobasoba and his children, details of the great migration.)

- Environment, education, and society in the Asia-Pacific, page 167, by John Fien, Helen Sykes, and David Yencken. (Reference to Lutunasobasoba and the great migration.)

- 'Viti: An Account of a Government Mission to the Vitian Or Fijian Islands, in the Years 1860-61, by Berthold Seemann. (Details on the Fijian belief system before Christianity and the introduction of Christianity.)

- The Years of Hope: Cambridge, colonial administration in the South Seas and cricket, by MR Philip Snow, page 31, (reference to Draunikau as Fijian Witchcraft).

- Dreaming and Storytelling, by Bert O. States, page 6. (Reference to the Fijian dream experience.)

- Body, Self, and Society: the view from Fiji, page 104, by Anne E. Becker, 1995. (Reference to dreams from a Fijian perspective as a form for spirits to communicate with the living.)

- Neither Cargo Nor Cult: Ritual Politics and the Colonial Imagination in Fiji, by Martha Kaplan, pages 49, 73, 150, 186 and 193. (References to dreams from a Fijian standpoint.)

- The Fijian Wanderers, by Ann Tyson Harvey, with assistance of Joji Suguturaga, 1969, Oceania Printer Suva Fiji. (Full tale of Tura, Lutunasobasoba and Degei and the great migration from Egypt.)

- Natural and Supernatural, by A. M. Hocart, Man, vol. 32, March 1932, pages 59–61 doi:10.2307/2790066 JSTOR 2790066. (Reference to the term Mana and its use.)

- "The Kalou-Vu (Ancestor-Gods) of the Fijians", by Basil H. Thomson, The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, vol. 24, 1895, pages 340-359, doi:10.2307/2842183. (Details on Lutunasobasoba, Degei and other Kalou Vu of Fiji.)

- A History of Fiji, by Ronald Albert Derrick, published 1946, Original from the University of Wisconsin - Madison, Digitized 23 Aug 2007, pages 7–8. (Details on Lutunasobasoba.)

Translations and transliterations[edit]

- Say it in Fijian, An Entertaining Introduction to the Language of Fiji, by Albert James Schütz, 1972.

- Lonely: Planet Fijian Phrasebook, by Paul Geraghty, 1994.

- Spoken Fijian: An Intensive Course in Bauan Fijian, with Grammatical Notes and Glossary, by Rusiate T. Komaitai, and Albert J. Schütz, Contributor Rusiate T. Komaitai, published 1971, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 0-87022-746-7.

External links[edit]

- Statistics on current belief systems in Fiji.

- Details on Fijian Mythology.

- Details on Fijian Mythology and origins

- Newspaper article on Blogspot with reference to Lutunasobasoba

- Fiji Times Newspaper article with reference to Lutunasobasoba also another article with reference to Lutunasobasoba[1]

- Oceania publications article describing the term Mana.

- Web article with reference to Fiji Religion and the term Mana