https://archive.org/details/caseagainstgod0000prie

Want to read

Buy on Kobo

Rate this book

The Case Against God

Gerald Priestland

3.60

5 ratings2 reviews

192 pages, Paperback

Published November 14, 1985

192 pages, Paperback

November 14, 1985 by Fount

12 people want to read

About the author

Gerald Priestland21 books2 followers

Educated at Charterhouse and New College, Oxford, Gerald Priestland began his career at the BBC writing obituaries. He eventually became a foreign correspondent for the BBC, covering politics in America. After suffering a nervous breakdown, Priestland converted to Christianity and became a Quaker. Upon recovering from his breakdown, he became involved in religious affairs, culminating in taking a role as the BBC's religious affairs correspondent. He published several books, including an autobiography, and delivered various lectures, before his death in 1991.

Gerald Priestland

Gerald Francis Priestland (26 February 1927 – 20 June 1991) was a foreign correspondent, presenter and, later, a religious commentator for the BBC.

Early life and work[edit]

Gerald Priestland was the son of (Joseph) Francis ('Frank') Edwin Priestland, Cambridge-educated publicity manager at Berkhamsted agricultural chemical business Cooper's (later Cooper, McDougall and Robertson- now part of GlaxoSmithkline), and a lieutenant in the Machine Gun Corps during the First World War, and Ellen Juliana, daughter of Colonel Alexander McWhirter Renny, of the 7th Bengal Lancers.[1] The owner of Cooper's was Frank Priestland's brother-in-law Sir Richard Ashmole Cooper, 2nd Baronet (married to his sister Alice).[2] Frank Priestland's father, Rev. Edward Priestland, was headmaster of Spondon House School in Derbyshire, having taken over from his father-in-law, Rev. Thomas Gascoigne.[3]

Gerald Priestland was educated at Charterhouse and New College, Oxford. He began his work at the BBC with a six-month spell writing obituary pieces for broadcast news. Indeed, he even jokingly wrote his own obituary shortly before leaving the job for a post as a sub-editor in the news gathering operation. In 1954, he became the youngest person (at 26 years) to work as a BBC foreign correspondent, having been sent by the controversial Editor of News, Tahu Hole, to the BBC's office in New Delhi. Between 1958 and 1961, Priestland was relocated to Washington, D.C. where he covered, among other things, the successful election of John F. Kennedy and the first US human spaceflight of Project Mercury.[4] Following this, he spent most of the next four years as the BBC's Middle East correspondent, including covering the funeral of Jawaharlal Nehru,[5] before requesting a transfer back to London as a television newsreader.

BBC2 opening night[edit]

Possibly Priestland's best known news broadcast occurred on the opening night of the BBC2 channel (Monday 20 April 1964). He had the onerous and unexpected task of anchoring the evening's transmission from the newsroom at Alexandra Palace as a consequence of an extensive power failure across London.[6] The channel's output that evening was restricted to repeated readings of the news and apologies for the loss of normal service and only lasted for about three hours.

Later life and work[edit]

During the late 1960s, Priestland was back in the USA as chief American correspondent where he covered such events as the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., the moon landing of the Apollo program and the outraged response of students to the Vietnam War. He returned to Britain at the end of the decade but his broadcasting duties were interrupted when he suffered a nervous breakdown. In the course of his recovery, Priestland became a devoted Quaker, despite having been a confirmed atheist in his youth.

Religious affairs[edit]

From the 1970s onward, Priestland became increasingly involved in religious broadcasting and was the BBC's religious affairs correspondent from 1977 to 1982. His "Priestland's Postbag" was a controversial part of Terry Wogan's BBC breakfast programme, drawing both praise and criticism. During this period, he reported on both Papal Elections of 1978 and introduced a Saturday morning programme on BBC Radio 4 entitled Yours Faithfully.

He gave the 1982 Swarthmore Lecture entitled, Reasonable Uncertainty: a Quaker approach to doctrine to the annual gathering of British Quakers. Priestland published his autobiography, Something Understood, in 1986, a work which he hastily altered before publication to express his true feelings about Tahu Hole, who had recently died: "He was a monster in every sense."

Priestland participated in a number of television and radio programmes for both the BBC and ITV until his death in 1991. After his death he received the rare honour (shared with John Reith, Huw Wheldon and Richard Dimbleby) of having a series of annually broadcast lectures named in his honour. He expressed his love of Cornwall in Postscript: with love to Penwith, published after his death.

Programmes[edit]

Priestland presented or featured on the following BBC programmes:

- BBC2 news (television programme) as a newsreader

- Sunday (radio programme) as a presenter

- Analysis (radio programme) as a presenter - 1974 to 1975

- Yours Faithfully (radio programme) as a presenter

- Priestland's Progress (radio programme) as a presenter[7] - 1981

- Desert Island Discs (radio programme) as a guest castaway[8] - 1984

- Radio Lives (radio programme) as the biography subject - 1995

Personal life[edit]

On 14 May 1949, Priestland married (Helen) Sylvia Rhodes (17 May 1924 - 14 January 2004), daughter of (Edward) Hugh Rhodes, C.B.E.,[9] of Turner's Wood, Hampstead Garden Suburb, a senior civil servant.[10] Sylvia Priestland was an artist. They had two sons and two daughters.[11][12]

Sources[edit]

- Leonard Miall, Inside the BBC – British Broadcasting Characters: p. 215–220. ISBN 0-297-81328-5

- Priestland, Gerald (1992). Postscript: with love to Penwith: two essays in Cornish History; with a foreword by Sylvia Priestland. Patten People, No.5. Newmill, Hayle, Cornwall: The Patten Press. ISBN 1-872229-02-6.

Printed material by Gerald Priestland[edit]

- America, the Changing Nation (1968)

- Frying Tonight: the saga of fish and chips (1972)

- The Future of Violence (1974)

- The Dilemmas of Journalism: speaking for myself (1979)

- West of Hayle River: (with Sylvia Priestland) (1980), new edition 1992 as Priestlands' Cornwall

- Priestland's Progress: One man's search for Christianity now (1981)

- Coming Home: an introduction to the Quakers (1981)

- Reasonable Uncertainty: a Quaker approach to doctrine (Swarthmore Lecture – 1982)

- Priestland: Right and Wrong (1983)

- Who Needs the Church?: the 1982 William Barclay Lectures (1983); Edinburgh, St Andrews Press ISBN 0715205536

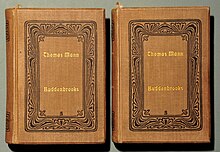

- The Case Against God (1984)

- For All the Saints (1985) – the 1985 James Backhouse Lecture (pamphlet – 18 pages)

- Something Understood: an autobiography (1986)[13]

- The Unquiet Suitcase: Priestland at Sixty (1988) – Gerald Priestland's diary for 1 year, from February 1987

- Postscript: With Love to Penwith: two essays in Cornish History; with a foreword by Sylvia Priestland (1992)

- My Pilgrim Way: late writings; edited by Roger Toulmin (1993)

- Three volumes of the Yours faithfully collected radio talks, the third volume having the title Gerald Priestland at Large.

References[edit]

- ^ Something Understood- An Autobiography, Gerald Priestland, Andre Deutsch Ltd, 1986, pp. 11-14

- ^ Something Understood- An Autobiography, Gerald Priestland, Andre Deutsch Ltd, 1986, pp. 11-12

- ^ Something Understood- An Autobiography, Gerald Priestland, Andre Deutsch Ltd, 1986, p. 10

- ^ Turnill, Reginald (2003). The Moonlandings: An Eyewitness Account. Cambridge University Press. p. 48. ISBN 9780521035354.

- ^ "Fond farewell to modern India's father". 13 September 2005. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- ^ "BBC Two's 50th anniversary: Disastrous launch remembered". BBC News. 2014.

- ^ "Priestland's Progress - BBC Radio 4 FM - 30 September 1981 - BBC Genome". genome.ch.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- ^ "BBC Radio 4 - Desert Island Discs, Gerald Priestland". BBC. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- ^ Who was Who: A Companion to Who's Who, A. & C. Black, 1981, p. 636

- ^ Something understood (Pbk edition) pp.78, 91 "With my exam of my life behind me, the Navy dismissed, and a job in hand, Sylvia and I were able to fix the wedding for May 14th 1949, three days before Sylvia's birthday"

- ^ George Wedell: Priestland, Gerald Francis (1927–1991), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2011, accessed 24 May 2015

- ^ The last page of Something understood gives more family information.

- ^ The title, "Something understood", is the last two words of George Herbert's poem "Prayer", referred to on page 8 (pbk edition). Monochrome illustrations, Hardback, 1986 ISBN 0233975004, paperback edition, Arrow, 1988 ISBN 0099523809

External links[edit]

- The launch night that never was – the BBC's own account of their attempts to maintain transmission during the power failure, featuring recorded footage of Gerald Priestland's efforts (accessed 2-17-03-08).

- Desert Island Discs broadcast by the BBC Radio 4 on 1984-03-03 (40 minutes) Roy Plomley interviews Gerald Priestland between his choice of eight pieces of music. Also chosen – the favourite of the eight, a book, other than the Holy Bible and Shakespeare's works and a luxury item, to accompany him on an indefinite stay on a deserted island.

- Priestland's Progress - Written summary of the 13 episodes, presented by Gerald Priestland in 1981, on his journey through Christianity.