중요한 학술대회가 있습니다. 같이 가실 분!!^^

All reactions:61이은선, 우희종 and 59 others

5 comments

8 shares

포스트휴머니즘

Posthumanism

| Part of a series on |

| Humanism |

|---|

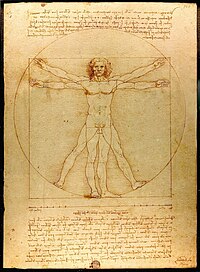

Leonardo da Vinci's Vitruvian Man (c. 1490) |

History |

Forms |

Organizations |

See also |

| Philosophy portal |

| Postmodernism |

|---|

| Preceded by Modernism |

| Postmodernity |

| Fields |

| Reactions |

| Related |

Posthumanism or post-humanism (meaning "after humanism" or "beyond humanism") is an idea in continental philosophy and critical theory responding to the presence of anthropocentrism in 21st-century thought.[1] Posthumanization comprises "those processes by which a society comes to include members other than 'natural' biological human beings who, in one way or another, contribute to the structures, dynamics, or meaning of the society."[2]

It encompasses a wide variety of branches, including:

- Antihumanism: a branch of theory that is critical of traditional humanism and traditional ideas about the human condition, vitality and agency.[3]

- Cultural posthumanism: A branch of cultural theory critical of the foundational assumptions of humanism and its legacy[4] that examines and questions the historical notions of "human" and "human nature", often challenging typical notions of human subjectivity and embodiment[5] and strives to move beyond "archaic" concepts of "human nature" to develop ones which constantly adapt to contemporary technoscientific knowledge.[6]

- Philosophical posthumanism: A philosophical direction[7] that draws on cultural posthumanism, the philosophical strand examines the ethical implications of expanding the circle of moral concern and extending subjectivities beyond the human species.[5][8]

- Posthuman condition: The deconstruction of the human condition by critical theorists.[9]

- Existential posthumanism:it embraces posthumanism as a praxis of existence.[10] Its sources are drawn from non-dualistic global philosophies, such as Advaita Vedanta, Taoism and Zen Buddhism, the philosophies of Yoga,[11] continental existentialism, native epistemologies and Sufism, among others. It examines and challenges hegemonic notions of being "human" by delving into the history and herstory of embodied practices of being human and, thus, expanding the reflection on human nature.

- Posthuman transhumanism: A transhuman ideology and movement which, drawing from posthumanist philosophy, seeks to develop and make available technologies that enable immortality and greatly enhance human intellectual, physical, and psychological capacities in order to achieve a "posthuman future".[12]

- AI takeover: A variant of transhumanism in which humans will not be enhanced, but rather eventually replaced by artificial intelligences. Some philosophers and theorists, including Nick Land, promote the view that humans should embrace and accept their eventual demise as a consequence of a technological singularity.[13] This is related to the view of "cosmism", which supports the building of strong artificial intelligence even if it may entail the end of humanity, as in their view it "would be a cosmic tragedy if humanity freezes evolution at the puny human level".[14][15][16]

- Voluntary human extinction: Seeks a "posthuman future" that in this case is a future without humans.[17]

Philosophical posthumanism[edit]

Philosopher Theodore Schatzki suggests there are two varieties of posthumanism of the philosophical kind:[18]

One, which he calls "objectivism", tries to counter the overemphasis of the subjective, or intersubjective, that pervades humanism, and emphasises the role of the nonhuman agents, whether they be animals and plants, or computers or other things, because "Humans and nonhumans, it [objectivism] proclaims, codetermine one another", and also claims "independence of (some) objects from human activity and conceptualization".[18]

A second posthumanist agenda is "the prioritization of practices over individuals (or individual subjects)", which, they say, constitute the individual.[18]

There may be a third kind of posthumanism, propounded by the philosopher Herman Dooyeweerd. Though he did not label it "posthumanism", he made an immanent critique of humanism, and then constructed a philosophy that presupposed neither humanist, nor scholastic, nor Greek thought but started with a different religious ground motive.[19] Dooyeweerd prioritized law and meaningfulness as that which enables humanity and all else to exist, behave, live, occur, etc. "Meaning is the being of all that has been created", Dooyeweerd wrote, "and the nature even of our selfhood".[20] Both human and nonhuman alike function subject to a common law-side, which is diverse, composed of a number of distinct law-spheres or aspects.[21] The temporal being of both human and non-human is multi-aspectual; for example, both plants and humans are bodies, functioning in the biotic aspect, and both computers and humans function in the formative and lingual aspect, but humans function in the aesthetic, juridical, ethical and faith aspects too. The Dooyeweerdian version is able to incorporate and integrate both the objectivist version and the practices version, because it allows nonhuman agents their own subject-functioning in various aspects and places emphasis on aspectual functioning.[22]

Emergence of philosophical posthumanism[edit]

Ihab Hassan, theorist in the academic study of literature, once stated: "Humanism may be coming to an end as humanism transforms itself into something one must helplessly call posthumanism."[23] This view predates most currents of posthumanism which have developed over the late 20th century in somewhat diverse, but complementary, domains of thought and practice. For example, Hassan is a known scholar whose theoretical writings expressly address postmodernity in society.[24] Beyond postmodernist studies, posthumanism has been developed and deployed by various cultural theorists, often in reaction to problematic inherent assumptions within humanistic and enlightenment thought.[5]

Theorists who both complement and contrast Hassan include Michel Foucault, Judith Butler, cyberneticists such as Gregory Bateson, Warren McCullouch, Norbert Wiener, Bruno Latour, Cary Wolfe, Elaine Graham, N. Katherine Hayles, Benjamin H. Bratton, Donna Haraway, Peter Sloterdijk, Stefan Lorenz Sorgner, Evan Thompson, Francisco Varela, Humberto Maturana, Timothy Morton, and Douglas Kellner. Among the theorists are philosophers, such as Robert Pepperell, who have written about a "posthuman condition", which is often substituted for the term posthumanism.[6][9]

Posthumanism differs from classical humanism by relegating humanity back to one of many natural species, thereby rejecting any claims founded on anthropocentric dominance.[25] According to this claim, humans have no inherent rights to destroy nature or set themselves above it in ethical considerations a priori. Human knowledge is also reduced to a less controlling position, previously seen as the defining aspect of the world. Human rights exist on a spectrum with animal rights and posthuman rights.[26] The limitations and fallibility of human intelligence are confessed, even though it does not imply abandoning the rational tradition of humanism.[27]

Proponents of a posthuman discourse, suggest that innovative advancements and emerging technologies have transcended the traditional model of the human, as proposed by Descartes among others associated with philosophy of the Enlightenment period.[28] Posthumanistic views were also found in the works of Shakespeare.[29] In contrast to humanism, the discourse of posthumanism seeks to redefine the boundaries surrounding modern philosophical understanding of the human. Posthumanism represents an evolution of thought beyond that of the contemporary social boundaries and is predicated on the seeking of truth within a postmodern context. In so doing, it rejects previous attempts to establish "anthropological universals" that are imbued with anthropocentric assumptions.[25] Recently, critics have sought to describe the emergence of posthumanism as a critical moment in modernity, arguing for the origins of key posthuman ideas in modern fiction,[30] in Nietzsche,[31] or in a modernist response to the crisis of historicity.[32]

Although Nietzsche's philosophy has been characterized as posthumanist,[33][34][35] Foucault placed posthumanism within a context that differentiated humanism from Enlightenment thought. According to Foucault, the two existed in a state of tension: as humanism sought to establish norms while Enlightenment thought attempted to transcend all that is material, including the boundaries that are constructed by humanistic thought.[25] Drawing on the Enlightenment's challenges to the boundaries of humanism, posthumanism rejects the various assumptions of human dogmas (anthropological, political, scientific) and takes the next step by attempting to change the nature of thought about what it means to be human. This requires not only decentering the human in multiple discourses (evolutionary, ecological and technological) but also examining those discourses to uncover inherent humanistic, anthropocentric, normative notions of humanness and the concept of the human.

Contemporary posthuman discourse[edit]

Posthumanistic discourse aims to open up spaces to examine what it means to be human and critically question the concept of "the human" in light of current cultural and historical contexts.[5] In her book How We Became Posthuman, N. Katherine Hayles, writes about the struggle between different versions of the posthuman as it continually co-evolves alongside intelligent machines.[36] Such coevolution, according to some strands of the posthuman discourse, allows one to extend their subjective understandings of real experiences beyond the boundaries of embodied existence. According to Hayles's view of posthuman, often referred to as "technological posthumanism", visual perception and digital representations thus paradoxically become ever more salient. Even as one seeks to extend knowledge by deconstructing perceived boundaries, it is these same boundaries that make knowledge acquisition possible. The use of technology in a contemporary society is thought to complicate this relationship.[37]

Hayles discusses the translation of human bodies into information (as suggested by Hans Moravec) in order to illuminate how the boundaries of our embodied reality have been compromised in the current age and how narrow definitions of humanness no longer apply. Because of this, according to Hayles, posthumanism is characterized by a loss of subjectivity based on bodily boundaries.[5] This strand of posthumanism, including the changing notion of subjectivity and the disruption of ideas concerning what it means to be human, is often associated with Donna Haraway's concept of the cyborg.[5] However, Haraway has distanced herself from posthumanistic discourse due to other theorists' use of the term to promote utopian views of technological innovation to extend the human biological capacity[38] (even though these notions would more correctly fall into the realm of transhumanism[5]).

While posthumanism is a broad and complex ideology, it has relevant implications today and for the future. It attempts to redefine social structures without inherently humanly or even biological origins, but rather in terms of social and psychological systems where consciousness and communication could potentially exist as unique disembodied entities. Questions subsequently emerge with respect to the current use and the future of technology in shaping human existence,[25] as do new concerns with regards to language, symbolism, subjectivity, phenomenology, ethics, justice and creativity.

Technological versus non-technological[edit]

Posthumanism can be divided into non-technological and technological forms.[39][40]

Non-technological posthumanism[edit]

While posthumanization has links with the scholarly methodologies of posthumanism, it is a distinct phenomenon. The rise of explicit posthumanism as a scholarly approach is relatively recent, occurring since the late 1970s;[1][41] however, some of the processes of posthumanization that it studies are ancient. For example, the dynamics of non-technological posthumanization have existed historically in all societies in which animals were incorporated into families as household pets or in which ghosts, monsters, angels, or semidivine heroes were considered to play some role in the world.[42][41][40]

Such non-technological posthumanization has been manifested not only in mythological and literary works but also in the construction of temples, cemeteries, zoos, or other physical structures that were considered to be inhabited or used by quasi- or para-human beings who were not natural, living, biological human beings but who nevertheless played some role within a given society,[41][40] to the extent that, according to philosopher Francesca Ferrando: "the notion of spirituality dramatically broadens our understanding of the posthuman, allowing us to investigate not only technical technologies (robotics, cybernetics, biotechnology, nanotechnology, among others), but also, technologies of existence."[43]

Technological posthumanism[edit]

Some forms of technological posthumanization involve efforts to directly alter the social, psychological, or physical structures and behaviors of the human being through the development and application of technologies relating to genetic engineering or neurocybernetic augmentation; such forms of posthumanization are studied, e.g., by cyborg theory.[44] Other forms of technological posthumanization indirectly "posthumanize" human society through the deployment of social robots or attempts to develop artificial general intelligences, sentient networks, or other entities that can collaborate and interact with human beings as members of posthumanized societies.

The dynamics of technological posthumanization have long been an important element of science fiction; genres such as cyberpunk take them as a central focus. In recent decades, technological posthumanization has also become the subject of increasing attention by scholars and policymakers. The expanding and accelerating forces of technological posthumanization have generated diverse and conflicting responses, with some researchers viewing the processes of posthumanization as opening the door to a more meaningful and advanced transhumanist future for humanity,[45][46][47] while other bioconservative critiques warn that such processes may lead to a fragmentation of human society, loss of meaning, and subjugation to the forces of technology.[48]

Common features[edit]

Processes of technological and non-technological posthumanization both tend to result in a partial "de-anthropocentrization" of human society, as its circle of membership is expanded to include other types of entities and the position of human beings is decentered. A common theme of posthumanist study is the way in which processes of posthumanization challenge or blur simple binaries, such as those of "human versus non-human", "natural versus artificial", "alive versus non-alive", and "biological versus mechanical".[49][41]

Relationship with transhumanism[edit]

Sociologist James Hughes comments that there is considerable confusion between the two terms.[50][51] In the introduction to their book on post- and transhumanism, Robert Ranisch and Stefan Sorgner address the source of this confusion, stating that posthumanism is often used as an umbrella term that includes both transhumanism and critical posthumanism.[50]

Although both subjects relate to the future of humanity, they differ in their view of anthropocentrism.[52] Pramod Nayar, author of Posthumanism, states that posthumanism has two main branches: ontological and critical.[53] Ontological posthumanism is synonymous with transhumanism. The subject is regarded as "an intensification of humanism".[54] Transhumanist thought suggests that humans are not post human yet, but that human enhancement, often through technological advancement and application, is the passage of becoming post human.[55] Transhumanism retains humanism's focus on the Homo sapiens as the center of the world but also considers technology to be an integral aid to human progression. Critical posthumanism, however, is opposed to these views.[56] Critical posthumanism "rejects both human exceptionalism (the idea that humans are unique creatures) and human instrumentalism (that humans have a right to control the natural world)".[53] These contrasting views on the importance of human beings are the main distinctions between the two subjects.[57]

Transhumanism is also more ingrained in popular culture than critical posthumanism, especially in science fiction. The term is referred to by Pramod Nayar as "the pop posthumanism of cinema and pop culture".[53]

Criticism[edit]

Some critics have argued that all forms of posthumanism, including transhumanism, have more in common than their respective proponents realize.[58] Linking these different approaches, Paul James suggests that 'the key political problem is that, in effect, the position allows the human as a category of being to flow down the plughole of history':

This is ontologically critical. Unlike the naming of 'postmodernism' where the 'post' does not infer the end of what it previously meant to be human (just the passing of the dominance of the modern) the posthumanists are playing a serious game where the human, in all its ontological variability, disappears in the name of saving something unspecified about us as merely a motley co-location of individuals and communities.[59]

However, some posthumanists in the humanities and the arts are critical of transhumanism (the brunt of James's criticism), in part, because they argue that it incorporates and extends many of the values of Enlightenment humanism and classical liberalism, namely scientism, according to performance philosopher Shannon Bell:[60]

Altruism, mutualism, humanism are the soft and slimy virtues that underpin liberal capitalism. Humanism has always been integrated into discourses of exploitation: colonialism, imperialism, neoimperialism, democracy, and of course, American democratization. One of the serious flaws in transhumanism is the importation of liberal-human values to the biotechno enhancement of the human. Posthumanism has a much stronger critical edge attempting to develop through enactment new understandings of the self and others, essence, consciousness, intelligence, reason, agency, intimacy, life, embodiment, identity and the body.[60]

While many modern leaders of thought are accepting of nature of ideologies described by posthumanism, some are more skeptical of the term. Haraway, the author of A Cyborg Manifesto, has outspokenly rejected the term, though acknowledges a philosophical alignment with posthumanism. Haraway opts instead for the term of companion species, referring to nonhuman entities with which humans coexist.[38]

Questions of race, some argue, are suspiciously elided within the "turn" to posthumanism. Noting that the terms "post" and "human" are already loaded with racial meaning, critical theorist Zakiyyah Iman Jackson argues that the impulse to move "beyond" the human within posthumanism too often ignores "praxes of humanity and critiques produced by black people",[61] including Frantz Fanon, Aime Cesaire, Hortense Spillers and Fred Moten.[61] Interrogating the conceptual grounds in which such a mode of "beyond" is rendered legible and viable, Jackson argues that it is important to observe that "blackness conditions and constitutes the very nonhuman disruption and/or disruption" which posthumanists invite.[61] In other words, given that race in general and blackness in particular constitute the very terms through which human-nonhuman distinctions are made, for example in enduring legacies of scientific racism, a gesture toward a "beyond" actually "returns us to a Eurocentric transcendentalism long challenged".[62] Posthumanist scholarship, due to characteristic rhetorical techniques, is also frequently subject to the same critiques commonly made of postmodernist scholarship in the 1980s and 1990s.

See also[edit]

- Bioconservatism

- Cyborg anthropology

- Posthuman

- Superhuman

- Technological change

- Technological transitions

- Transhumanism

References[edit]

- ^ Jump up to:a b Ferrando, Francesca (2013). "Posthumanism, Transhumanism, Antihumanism, Metahumanism, and New Materialisms: Differences and Relations" (PDF). Existenz. ISSN 1932-1066. Retrieved 2014-03-14.

- ^ Gladden, Matthew (2018). Sapient Circuits and Digitalized Flesh: The Organization as Locus of Technological Posthumanization (PDF) (second ed.). Indianapolis, IN: Defragmenter Media. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-944373-21-4. Retrieved March 14, 2018. Elsewhere (p. 35) in the same text Gladden proposes a longer definition, stating that "The processes of posthumanization are those dynamics by which a society comes to include members other than 'natural' biological human beings who, in one way or another, contribute to the structures, activities, or meaning of the society. In this way, a society comes to incorporate a diverse range of intelligent human, non-human, and para-human social actors who seek to perceive, interpret, and influence their shared environment and who create knowledge and meaning through their networks and interactions."

- ^ J. Childers/G. Hentzi eds., The Columbia Dictionary of Modern Literary and Cultural Criticism (1995) p. 140-1

- ^ Esposito, Roberto (2011). "Politics and human nature". Angelaki. 16 (3): 77–84. doi:10.1080/0969725X.2011.621222.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g Miah, A. (2008) A Critical History of Posthumanism. In Gordijn, B. & Chadwick R. (2008) Medical Enhancement and Posthumanity. Springer, pp.71-94.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Badmington, Neil (2000). Posthumanism (Readers in Cultural Criticism). Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-76538-8.

- ^ Ferrando, Francesca (2019-06-27). Philosophical Posthumanism. Bloomsbury Reference Online. ISBN 9781350059498. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- ^ Morton, Timothy, 1968 (9 March 2018). Being ecological. Cambridge, Massachusetts. ISBN 978-0-262-03804-1. OCLC 1004183444.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Hayles, N. Katherine (1999). How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics. University Of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-32146-2.

- ^ Ferrando, Francesca (2024-02-14). The Art of BeingPosthuman. Polity. ISBN 9781509548965. Retrieved 25 April 2024.

- ^ Banerji, Debashish (2021). "Traditions of Yoga in Existential Posthuman Praxis". Journal of Posthumanism. 1 (2): 1–6. doi:10.33182/jp.v1i2.1777.

- ^ Bostrom, Nick (2005). "A history of transhumanist thought" (PDF). Retrieved 2006-02-21.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Oliver Krüger: Virtual Immortality. God, Evolution, and the Singularity in Post- and Transhumanism., Bielefeld: transcript 2021 - ^ "The Darkness Before the Right". Archived from the original on 2016-05-17. Retrieved 2015-11-28.

- ^ Hugo de Garis (2002). "First shot in Artilect war fired". Archived from the original on 17 October 2007.

- ^ "Machines Like Us interviews: Hugo de Garis". 3 September 2007. Archived from the original on 7 October 2007.

gigadeath – the characteristic number of people that would be killed in any major late 21st century war, if one extrapolates up the graph of the number of people killed in major wars over the past 2 centuries

- ^ Garis, Hugo de. "The Artilect War - Cosmists vs. Terrans" (PDF). agi-conf.org. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ Torres, Phil (12 September 2017). Morality, foresight, and human flourishing : an introduction to existential risks. Durham, North Carolina. ISBN 978-1-63431-143-4. OCLC 1002065011.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Schatzki, T.R. 2001. Introduction: Practice theory, in The Practice Turn in Contemporary Theory eds. Theodore Schatzki, Karin Knorr Cetina & Eike Von Savigny. pp. 10-11

- ^ "Ground Motives - the Dooyeweerd Pages".

- ^ Dooyeweerd, H. (1955/1984). A new critique of theoretical thought (Vol. 1). Jordan Station, Ontario, Canada: Paideia Press. P. 4

- ^ "'law-side'".

- ^ "his radical notion of subject-object relations".

- ^ Hassan, Ihab (1977). "Prometheus as Performer: Toward a Postmodern Culture?". In Michel Benamou, Charles Caramello (ed.). Performance in Postmodern Culture. Madison, Wisconsin: Coda Press. ISBN 978-0-930956-00-4.

- ^ Thiher, Allen (1990). "Postmodernism's Evolution as Seen by Ihab Hassan" (PDF). Contemporary Literature. 31 (2): 236–239. doi:10.2307/1208589. JSTOR 1208589. Retrieved December 19, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Wolfe, C. (2009). What is Posthumanism? University of Minnesota Press. Minneapolis, Minnesota.

- ^ Evans, Woody (2015). "Posthuman Rights: Dimensions of Transhuman Worlds". Teknokultura. 12 (2). doi:10.5209/rev_TK.2015.v12.n2.49072.

- ^ Addressed repeatedly, albeit differently, among scholars, e.g. Stefan Herbrechter, Posthumanism: A Critical Analysis (London: A&C Black, 2013), 126 and 196-97. ISBN 1780936907, 9781780936901

- ^ Badmington, Neil. "Posthumanism". Blackwell Reference Online. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- ^ Herbrechter, S.; Callus, I.; Rossini, M.; Grech, M.; de Bruin-Molé, M.; Müller, C.J. (2022). Palgrave Handbook of Critical Posthumanism. Springer International Publishing. p. 708. ISBN 978-3-031-04958-3. Retrieved 2023-03-20.

- ^ "Genealogy". Critical Posthumanism Network. 2013-10-01. Retrieved 2019-07-30.

- ^ Wallace, Jeff (December 2016). "Modern". The Cambridge Companion to Literature and the Posthuman. pp. 41–53. doi:10.1017/9781316091227.007. ISBN 9781316091227. Retrieved 2019-07-30.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Borg, Ruben (2019-01-07). Fantasies of Self-Mourning: Modernism, the Posthuman and the Finite. Brill Rodopi. doi:10.1163/9789004390355. ISBN 9789004390355. S2CID 194194777.

- ^ Posthumanism in the Age of Humanism: Mind, Matter, and the Life Sciences after Kant. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. 4 October 2018. ISBN 9781501335693.

- ^ The Routledge Handbook of Biopolitics. Routledge. 5 August 2016. ISBN 9781317044079.

- ^ Philosophical Posthumanism. Bloomsbury. 27 June 2019. ISBN 9781350059481.

- ^ Cecchetto, David (2013). Humanesis: Sound and Technological Posthumanism. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- ^ Hayles, N. Katherine (5 April 2017). Unthought: the power of the cognitive nonconscious. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-44774-2. OCLC 956775338.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Gane, Nicholas (2006). "When We Have Never Been Human, What Is to Be Done?: Interview with Donna Haraway". Theory, Culture & Society. 23 (7–8): 135–158. doi:10.1177/0263276406069228.

- ^ Herbrechter, Stefan (2013). Posthumanism: A Critical Analysis. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-7809-3690-1.After referring (p. 3) to "the current technology-centred discussion about the potential transformation of humans into something else (a process that might be called 'posthumanization')," Herbrechter offers an analysis of Lyotard's essay "A Postmodern Fable," in which Herbrechter concludes (p. 7) that "What Lyotard's sequel to Nietzsche's fable shows is that, on the one hand, there is no point in denying the ongoing technologization of the human species, and, on the other hand, that a purely technology-centred idea of posthumanization is not enough to escape the humanist paradigm."

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Gladden, Matthew (2018). Sapient Circuits and Digitalized Flesh: The Organization as Locus of Technological Posthumanization (PDF) (second ed.). Indianapolis, IN: Defragmenter Media. ISBN 978-1-944373-21-4. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Herbrechter, Stefan (2013). Posthumanism: A Critical Analysis. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-7809-3690-1.

- ^ Graham, Elaine (2002). Representations of the Post/Human: Monsters, Aliens and Others in Popular Culture. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-8135-3058-X.

- ^ Ferrando, Francesca (2016). "Humans Have Always Been Posthuman: A Spiritual Genealogy of the Posthuman". In Banerji, Debashish; et al. (eds.). Critical Posthumanism and Planetary Futures (1st ed.). New York: Springer. pp. 243–256. ISBN 9788132236375. Retrieved 2018-08-08.

- ^ The Cyborg Handbook (1995). Chris Hables Gray, editor. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415908498.

- ^ Moravec, Hans (1988). Mind Children: The Future of Robot and Human Intelligence. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-57618-7.

- ^ Kurzweil, Ray (2005). The Singularity is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology. New York, NY: Penguin. ISBN 9781101218884.

- ^ Bostrom, Nick (2008). "Why I Want to Be a Posthuman When I Grow Up" (PDF). In Gordijn, Bert; Chadwick, Ruth (eds.). Medical Enhancement and Posthumanity. Springer Netherlands. pp. 107–137. ISBN 978-1-4020-8851-3. Retrieved August 16, 2018.

- ^ Fukuyama, Francis (2002). Our Posthuman Future: Consequences of the Biotechnology Revolution. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. ISBN 9781861972972.

- ^ Ferrando, Francesca (2013). "Posthumanism, Transhumanism, Antihumanism, Metahumanism, and New Materialisms: Differences and Relations." Existenz: An International Journal in Philosophy, Religion, Politics, and the Arts 8 (2): 26-32. ISSN 1932-1066. Ferrando notes (p. 27) that such challenging of binaries constitutes part of "the post-anthropocentric and post-dualistic approach of (philosophical, cultural, and critical) posthumanism."

- ^ Jump up to:a b Ranisch, Robert (January 2014). "Post- and Transhumanism: An Introduction". Retrieved 25 August 2016.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ MacFarlane, James (2014-12-23). "Boundary Work: Post- and Transhumanism, Part I, James Michael MacFarlane". Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- ^ Umbrello, Steven (2018-10-17). "Posthumanism". Con Texte. 2 (1): 28–32. doi:10.28984/ct.v2i1.279. ISSN 2561-4770.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c K., Nayar, Pramod (2013-10-28). Posthumanism. Cambridge. ISBN 9780745662404. OCLC 863676564.

- ^ Cary., Wolfe (2010). What is posthumanism?. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9780816666157. OCLC 351313274.

- ^ Wolfe, Cary (2010). What is Posthumanism?. U of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9780816666140.

- ^ Deretić, Irina; Sorgner, Stefan Lorenz, eds. (2016-01-01). From Humanism to Meta-, Post- and Transhumanism?. doi:10.3726/978-3-653-05483-5. ISBN 9783653967883. Retrieved 2020-10-08.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Umbrello, Steven; Lombard, Jessica (2018-12-14). "Silence of the Idols: Appropriating the Myth of Sisyphus for Posthumanist Discourses". Postmodern Openings. 9 (4): 98–121. doi:10.18662/po/47. hdl:2318/1686606. ISSN 2069-9387.

- ^ Winner, Langdon (2005). "Resistance is Futile: The Posthuman Condition and Its Advocates". In Harold Bailie, Timothy Casey (ed.). Is Human Nature Obsolete?. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, October 2004: M.I.T. Press. pp. 385–411. ISBN 978-0262524285.

- ^ James, Paul (2017). "Alternative Paradigms for Sustainability: Decentring the Human without Becoming Posthuman". In Karen Malone; Son Truong; Tonia Gray (eds.). Reimagining Sustainability in Precarious Times. Ashgate. p. 21.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Zaretsky, Adam (2005). "Bioart in Question. Interview". Archived from the original on 2013-01-15. Retrieved 2007-01-28.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Jump up to:a b c Jackson 2015, p. 216.

- ^ Jackson 2015, p. 217.

Works cited[edit]

- Jackson, Zakiyyah Iman (June 2015). "Outer Worlds: The Persistence of Race in Movement 'Beyond the Human'". GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies. 21 (2-3: Queer Inhumanisms): 215–218. Via Project Muse (subscription required).

새로운 철학적 인간학…트랜스휴머니즘과 포스트휴머니즘

조창오 부산대·철학

승인 2021.03.28 19:00

댓글 0페이스북

트위터

카카오스토리

URL복사

기사공유하기

스크랩

프린트

메일보내기

글씨키우기

https://www.unipress.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=3335

■ 역자가 말하다_ 『트랜스휴머니즘과 포스트휴머니즘』 (야니나 로 지음, 조창오 옮김, 부산대학교출판문화원, 269쪽, 2021.02)

현시대 인문학에서 가장 인기 있는 개념이라면 ‘포스트휴머니즘’이라 할 수 있다. 마치 90년대 초에 ‘포스트모더니즘’이 인기를 끌었던 것과 유사한 현상이다. ‘포스트모더니즘’은 ‘모더니즘’ 이후의 사조를 가리킨다. 그렇다면 ‘포스트휴머니즘’은 ‘휴머니즘’ 이후의 사조를 가리키는가? 그렇다. ‘포스트모더니즘’의 경우와 마찬가지로 여기서 ‘포스트’는 단순히 시간적인 선후만을 의미하지는 않는다. 그렇다면 어떠한 경우의 수가 있을까? 휴머니즘 이후의 포스트휴머니즘은 휴머니즘의 정신을 계승하면서도 이를 발전적으로 확장한 것이거나 휴머니즘에 반대하는 반휴머니즘일 수 있다. 또 다른 가능성은 휴머니즘에 단순히 반대하는 게 아니라 이를 초월하는 것일 수 있다.

여기서 휴머니즘을 발전적으로 확장한 관점이 바로 ‘트랜스휴머니즘’과 ‘기술적 포스트휴머니즘’이다. 휴머니즘은 인간이 스스로 자기 노력을 통해 향상시켜야 한다는 이상을 가지고 있다. 인간은 태어나면 생물학적으로 인간일 수 있지만, 인간다운 인간은 아니다. 그래서 신체적이고 정신적인 교육을 통해 스스로를 단련하고 발전시켜야 진정한 인간이 될 수 있다. 휴머니즘은 ‘진정한 인간이 무엇인지 탐구하고, 진정한 인간이 되도록 노력하자’를 자신의 모토로 삼는다.

‘트랜스휴머니즘’에서 ‘트랜스’라는 표현은 첫째로 ‘어떤 것을 초월한다’는 뜻을 가진다. 초창기 트랜스휴머니스트들이 이런 의미를 선호했다. 그래서 트랜스휴머니즘은 자연적인 인간을 초월하려는 ‘진화적 인본주의’를 의미했다. 그런데 자연적 진화는 인간이 원한다고 해서 이루어지는 것은 아니다. 인간에게 가능하고 효율적인 인위적 진화는 기술을 통한 인간 향상이다. 그래서 트랜스휴머니즘은 기술적 수단을 이용해 자연적 인간을 점점 더 업그레이드해서 ‘완벽한 인간’으로 나아가는 것을 목적으로 삼는다. 예를 들어 비타민을 매일 먹어 신체적 능력을 향상시키거나, 또는 특정 약물을 통해 정신적 능력을 향상시키는 것도 한 예고, 칩을 신체에 삽입하거나 또는 냉동 보관을 통해 미래 기술을 이용하여 불멸을 획득하려는 노력도 해당 예라 할 수 있다.

물론 휴머니즘과는 큰 차이가 있다. 휴머니즘은 ‘교육’이란 과정을 통해 인간을 인간다운 인간으로 이끌려 한다. 여기서 ‘인간다운 인간’은 정신적 능력과 신체적 능력을 향상시킨 인간, ‘자율성’을 가진 윤리적이고 건강한 인간이라 할 수 있다. 이에 반해 트랜스휴머니즘에서 목표로 설정한 ‘완벽한 인간’은 모든 점에서 뛰어난 인간이다. 하지만 ‘모든 점에서 뛰어난’이란 게 과연 어떤 의미인지는 애매하다. 휴머니즘은 단순히 뛰어난 인간이 아니라 ‘자율성’을 갖춘 인간을 목표로 한다. 그런데 트랜스휴머니즘은 자율성을 가지고 자기 계발하는 인간이 아니라 철저히 기술에 의존하여 자신을 향상시킨 인간을 목표로 한다. 즉 이때의 인간은 자율성을 상실하고, 기계에 철저히 의탁해 있는 인간이다.

기술적 포스트휴머니즘은 트랜스휴머니즘보다 훨씬 더 과격하다. 트랜스휴머니즘은 인간의 육체를 강조하고, 육체를 기술적으로 향상시킴으로써 인간의 정신적이고 육체적인 능력을 향상시키려 한다. 이에 반해 기술적 포스트휴머니즘은 육체를 인간의 감옥으로 여기고 인간이 육체에서 벗어나 새로운 하드웨어로 옮겨가는 것을 목표로 한다. 영화 <트렌센덴스>에서 주인공은 육체적 허약함 때문에 육체 대신 슈퍼컴퓨터로 마음을 복사하여 계속 생존해간다. 이것이 소위 말하는 ‘마음 업로딩’이다. 여기서 전제하고 있는 것은 ‘나라는 존재’가 단순히 ‘마음’, 그것도 복사할 수 있는 데이터에 불과하다는 것이다. ‘나라는 존재’가 데이터에 불과하고 더 좋은 하드웨어로 복사할 수 있다면, 나는 불멸하게 되며, 더 좋은 하드웨어의 도움으로 더 뛰어난 존재가 될 수 있을 것이다. 특히 기술적 포스트휴머니즘은 ‘특이점’을 강조하면서 강한 인공지능이 등장하게 되면, 이 존재야말로 인간보다 뛰어난 인간이자, 진정한 인간이라고 여기며, 이 존재를 통해 육체를 지닌 인간을 극복할 수 있다고 주장한다. 이는 단순히 기계에 의한 인간 지배가 아니라 더 뛰어난 지성적 존재에 의한 인간 지배다.

원서 & 야니나 로

원서 & 야니나 로기술적 포스트휴머니즘에서 말하는 ‘포스트휴먼’은 이처럼 인간의 육체에서 벗어난 지성적 존재다. 기술적 포스트휴머니스트들은 ‘트랜스휴먼’이 단순히 자신들이 이야기하는 ‘포스트휴먼’으로 오기 위한 과도기적 존재라고 규정한다. 이것이 바로 ‘트랜스휴먼’의 두 번째 의미이다. ‘트랜스’는 ‘어디에서 어디로’를 뜻한다. 즉 ‘어떤 출발점에서 목적지로 가는 도중’이라는 뜻이다. 이런 의미에서 ‘트랜스휴먼’은 기술적 포스트휴머니즘이 말하는 ‘포스트휴먼’으로 가는 과도기적 존재를 의미한다.

비판적 포스트휴머니즘은 휴머니즘을 계승하기보다는 이를 극복하려 한다. 휴머니즘은 항상 인간과 동물, 지성과 감성, 남성과 여성 등 이분법적인 틀을 통해 한쪽을 깎아내림으로써 다른 한쪽을 드높였다. 대표적인 것이 바로 ‘인간다움’의 강조다. 인간다움은 ‘동물다움’의 반대이며, ‘동물다움’은 감성적 존재, 여성적 존재와 연관되는 데 반해, 인간은 지성적 존재이며, 남성적 존재다. 휴머니즘의 기본적인 논리는 이 이분법적인 틀 위에서 이루어진다. 반인본주의는 인본주의의 반대로서 이 이분법적인 틀을 그대로 인정하면서 인간보다 ‘동물’을, 남성보다 ‘여성’을 더 우월하게 여긴다. 비판적 포스트휴머니즘은 인본주의와 반인본주의가 공동으로 전제하는 ‘이분법적인 틀’ 자체를 비판하며, 이를 극복하자고 주장한다. 그래서 인간과 동물을 서로 구별하기보다는 인간과 동물의 ‘관계’ 자체를 중시하고, 양자를 이 관계의 대등한 관계 항으로 바라보자는 것이다.

세 입장 모두 ‘포스트휴먼’에 대해 이야기하지만, 그 의미는 위에서 살펴본 것처럼 그 의미가 다르다. 트랜스휴머니즘은 기술적으로 향상된 육체를 가진 인간을 ‘포스트휴먼’이라 하는데, 실질적으로는 이는 ‘향상된 인간’인 ‘트랜스휴먼’이라 할 수 있고, 기술적 포스트휴머니즘은 육체를 벗어난 순수 지성으로서의 인간을 목표로 설정한다는 점에서 ‘포스트휴먼’, 즉 인간을 극복한 인간이라 할 수 있다. 비판적 포스트휴머니즘은 휴머니즘의 틀 자체를 극복한 인간을 ‘포스트휴먼’이라 부른다.

조창오 부산대·철학

연세대학교 국문과와 대학원 철학과를 졸업하고 독일 로이파나 대학교에서 『현대의 멜랑콜리적 구성. 헤겔의 현대비극 개념』으로 박사학위를 받았다. 울산대 철학과 객원교수, 부산외대 만오교양대학, 남부대 교양학부 교수를 거쳐 현재 부산대 철학과 교수로 있으며 연구 중점은 미학, 사회철학, 기술철학 등이다. 저서 『예술의 종말과 현대예술』 외에 다수의 논문이 있으며 번역서로는 『박물관 이론 입문』, 『늙어감에 대하여』 등이 있다.

저작권자 © 대학지성 In&Out 무단전재 및 재배포 금지

조창오 부산대·철학다른기사 보기

조창오 부산대·철학다른기사 보기페이스북

트위터

카카오스토리

URL복사

기사공유하기