무속신앙 빙의(憑依)

집필자 이정재(李丁宰)

연관 표제어 순천삼설양굿

조선신가유편심리종교학적인 용어로 초월적 의식세계를 경험하거나 인식하는 상태.

용왕상

제금

장군개

부군

신내림

염불

안산잿머리성황당

호남굿 무복

내용

빙의(possession)는 엘리아데(M. Eliade)의 정의에 따르면 탈혼(ecstacy)에 대응되는 개념이다. 그는 시베리아의 샤머니즘을 기술하는 과정에서 이 두 용어를 구별하여 쓰고 있다. 탈혼은 무당의 혼이 육체를 이탈하여 신계를 여행하는 것이고 빙의는 외부의 신령이 무당의 몸 안으로 들어오는 것으로 보았다. 전자의 전통은 유목과 수렵을 경제기반으로 하는 북방 시베리아인에게서 주로 발견되고, 빙의 현상은 정착생활을 하는 농경사회의 무당들에게서 발견이 된다고 하였다. 북방 샤먼의 경우 무당의 영이 초월적 공간을 여행 할 때 단독으로 다니는 것이 아니라 여럿의 조력신을 동반한다. 이는 빙의의 과정에서 무당의 몸주신 외의 여러 주력신이 병존하는 것과 동일하다. 무당이 굿을 할 때 당면한 문제를 해결하는 데 도움을 주기 위한 것이다.

김태곤과 이정재가 1995년에 조사한 시베리아의 자료에 근거할 때 엘리아데가 주장한 북방인들의 엑스터시 현상은 절대적이지 않았고, 더구나 이들에게서도 빙의 현상이 드러나고 있음이 밝혀졌다. 탈혼과 빙의의 공간적·주제적 이분법이 분명하게 대치되어 드러난 것은 아니라 할 수 있다.

빙의를 학술적으로 규명하는 데는 한계가 있다. 그것은 이성적 지식의 영역이라기보다는 체험의 영역이기 때문이다. 무속을 이해하는 데 빙의 개념의 풍부하고 정확한 설명이 필요한데 이를 극복하기 위한 노력이 종종 이루어진다. 무속학자 중에서 무속의 진정한 세계를 경험하기 위하여 스스로 무당이 된다거나, 전통춤의 과정에서 경험하는 빙의적 현상을 논문화하는 것이 그 예이다. 여기에는 부족한 부분이 있으나 빙의 혹은 빙의 유사현상이 가지는 무속과 관련 예술세계 내의 위상과 의미가 중요한 핵심을 이룬다.

무당의 빙의현상을 크게 세 가지로 구분하기도 한다. 즉 정지 영상, 동영상, 소리 등이다. 그러나 이는 너무 단순한 요약에 불과하다. 빙의현상의 형태를 좀 더 구체적으로 정리하면 몸의 자동적인 움직임 유도, 초월적 영상체험, 초월적 소리체험, 공수, 신체 통증, 직감과 영감, 예지몽, 개인성향의 변화, 감정전이, 초월적이고 신비한 성(sex)체험 등이다. 이 모두가 무당이 굿을 할 때 사용하는 제반 요소, 즉 무무, 무가, 무복, 무구, 공수, 점, 예언 등과 밀접한 관련이 있다. 성의 신비체험은 성과 속의 일체화, 성속의 추월이라는 상징성을 지닌다. 즉 양성구유 과정으로의 현상으로 분석된다.

참조

신내림

참고문헌

M. Eliade, Cosmos and History (엘리아데) M. Eliade 1988, Mythos and Wirklichkeit (엘리아데, 1988) 시베리아의 샤마니즘과 한국무속 (이정재, 비교민속학회 14, 1997) 빙의현상 연구 (이철진, 김정명, 선무학술논집 15, 2005) 한국무속인열전 (서정범, 우석, 2006)

===

불교상식/교리앱으로보기

빙의(憑依)란,,,무엇인가?작성자내사랑천유|작성시간13.04.11|조회수143목록댓글 0글자크기 작게가글자크기 크게가

빙의(憑依)란 무엇인가?

빙의(憑依)는 죽은 사람의 영혼이 살아 있는 사람의 몸 안에 들어오는 현상을 말한다.

사람의 몸은 하나의 영혼만이 살수있는 집이며,각 영혼은 자신만의 고유한 영적

파장을 지니고 있다.

그런데 그 집에 어떤 연유로 파장이 다른 영혼이 들어오게 되면

그 사람은 정신적으로나 육체적으로 문제를 겪게 된다.

일종의 에너지인 생명체는 영혼에 거부 반응이 일어나기 시작하는 데

본래의 신체적 리듬에 혼란(거부반응)이 올 수 있고,

그 혼란이 깊어질수록 현대의학으로는 치료가

불가능한 심령(心靈)인 질병을 앓게 된다.

이렇게 생명 에너지가 혼란이 오면 생명 에너지 응집체인 혈액에 이상을

가져올수 있다,

죽은 사람의 영혼이 살아 있는 사람의 몸에 빙의(憑依) 하는 이유에 대해서는

여러가지 설이 있는데, 대부분의 빙의는 이승에 대한 집착과 미련을 떨쳐버리지

못하고 그 미망(迷妄)으로 인해 구천(九天)을 헤매고 있는

영혼(靈魂)들로 인해 발생한다.

특히 돌발적인 사고로 미쳐 자신의 죽음을 인지하지 못하고 죽음을

맞이한 영혼들은 상실한 육체에 대한 혼란과 슬픔에 빠져 주위에서 유체(幽體)가

발달되어 있고 영파가 맞는 사람을 발견하면 육신(肉身)에 머물고 싶은

본능적인 욕구를 느끼게 된다.

또 생전(生前)에 미쳐 풀지 못한 원한(怨恨)을 품은 채 죽은 영혼(靈魂)은

원한의 대상이 되었던 사람의 몸에 빙의 하는 경우가 많은데

이런 원념(怨念)을 가진 영혼들은 대부분 상대방에게 신체적 영적인

불이익을 주기 위해 끈질기게 그 사람을 괴롭히게 된다.

드물기는 하지만

심한 경우에는 그 사람의 목숨을 노리고 덤벼드는 일종의 악령(惡靈)

도 볼 수 있다.

이런 경우에는 매우 위험한 상황이 벌어질 수 도 있다.

♣빙의(憑依)된 사람들의 특징!

1.시선이 불안정하거나 행동이 산만하다.

2.코와 입으로 이상한 소리를 자주 낸다.(쓸데없이 킁킁거리거나 숨을 들이 마신다)

3.눈의 흰자위가 항상 충혈 되어 있다.

4.뚜렷한 이유가 없는 심인성 질환(신경성)을 앓고 있다.

5.손발 유난히 차고 양 어깨가 이유없이 아프다(심장있는 왼쪽 어깨가 더 심하다

고 함)

6.신체적 통증이 불규칙하게 여러 곳으로 옮겨 다닌다.

7.계속해서 악몽에 시달리거나 꿈속에서 죽은 사람의 얼굴을 자주 본다.

8.멀쩡하다가 갑자기 정신이상 증세를 보인다.

9.하느님이나 부처님 이야기를 하면 이유도 없이 싫어한다.

10.뚜렷한 원인도 없이 심한 현기증에 시달린다.

11.삶에 대한 의욕이 없으며 자살 충동을 자주 느낀다.

12.몸이 무겁고, 심장이 두근거리거나 피로감,소화불량,두통 등이 심합니다.

===

빙의

26개 언어

문서

토론

읽기

편집

역사 보기

도구

위키백과, 우리 모두의 백과사전.

다른 뜻에 대해서는 빙의 (동음이의) 문서를 참고하십시오.

다른 뜻에 대해서는 빙의 (동음이의) 문서를 참고하십시오.빙의(憑依, 영어: spirit possession)는 영, 외계인, 악령, 신이 인체를 통제한다는 가정이다. 빙의 개념은 기독교[1], 불교, 아이티 부두교, 위카, 힌두교, 이슬람교 등 수많은 종교, 그리고 동남아시아와 아프리카 전통에 존재한다. NIMH(National Institute of Mental Health) 기금 지원을 받은 1969년 연구에 따르면, 빙의적 믿음은 전 세계 모든 지역 488개 사회 샘플 가운데 74%에서 존재하는 것으로 밝혀졌다.[2] 발견되는 문화적 문맥에 따라 빙의는 자발적일 수도 있고 비자발적일 수도 있으며, 빙의되는 자에게 긍정적인 효과나 해로운 효과를 미치는 것으로 간주할 수 있다. 빙의 컬트에서 빙의는 남성보다 여성 사이 더 흔하다.[3][4]

예시[편집]개인아넬리제 미헬

같이 보기[편집]성령세례

악마학

열광

구마 (종교)

쿤달리니

영매

강령술

각주[편집]

↑ Mark 5:9, Luke 8:30

↑ Bourguignon, Erika; Ucko, Lenora (1969). 《Cross-Cultural Study of Dissociational States》. The Ohio State University Research Foundation with National Institute of Mental Health grant.

↑ 1981 Kehoe, Alice B., and Giletti, Dody H., Women's Preponderance in Possession Cults: The Calcium Deficiency Hypothesis Extended, American Anthropologist, New Series,. 83(3): 549–561

↑ Lewis, I.M. 1966 Spirit Possession and Deprivation Cults. Man, New Series: 1 (3): 307–329.

외부 링크[편집]Calmet, Augustine (1751). 《Treatise on the Apparitions of Spirits and on Vampires or Revenants: of Hungary, Moravia, et al. The Complete Volumes I & II. 2016》. ISBN 978-1-5331-4568-0.

===

目次の表示・非表示を切り替え

憑依

26の言語版

ページ

ノート

閲覧

編集

履歴表示

ツール

出典: フリー百科事典『ウィキペディア(Wikipedia)』

憑依(ひょうい)は、霊などが乗り移ること[1][2]。憑(つ)くこと[1]。憑霊[3]、神降ろし、神懸り、神宿り、憑き物ともいう。とりつく霊の種類によっては、悪魔憑き、狐憑きなどと呼ぶ場合もある[2]。現代でも脳から独立した意識の存在として憑依現象の報告が研究されており、近年はそうした脳から独立した意識の存在を報告する総説も増え、本格的な学問分野となっている[4]。医学の世界では、憑依は精神疾患の一種と見なされることもあるが[5]、憑依は儀式の場での憑依と精神疾患による憑依に分類され、必ずしも精神疾患とは限らない[6]。宗教学では「つきもの」を「ある種の霊力が憑依して人間の精神状態や運命に劇的な影響を与えるという信念」とする[7]。

「憑依」という表現は、ドイツ語の Besessenheit や英語の (spirit) possession などの学術語を翻訳するために、昭和ごろ、特に第二次世界大戦後から用いられるようになったと推定されている(下記「訳語の歴史」を参照)。ファース(Firth, R)によれば、「(シャーマニズムにおける)憑依(憑霊)はトランスの一形態であり、通常ある人物に外在する霊がかれの行動を支配している証拠」と位置づけられる。脱魂(英: ecstasy もしくは soul loss)や憑依(英: possession)はトランス状態における接触・交通の型である[8]。

訳語の歴史[編集]

人類学、宗教学、民俗学などの学術用語として用いられるようになった「憑依」あるいは「憑霊」という表現は、明らかにドイツ語の Besessenheit や英語の(spirit) possession などの翻訳語であり、欧米の学者らが使用する学術用語が日本の学界に輸入されたものである、と池上良正は指摘した[9]。1941年(昭和25年)のある学術文献[10]には「憑依」の語が登場した。一般化したのは第二次世界大戦後だろうと推定される[3][9]。

「憑依」という学術用語が用いられるようになって後は、この用語に関して、様々な理論化や類型化が行われてきた[3]。例えば、憑依という用語にとらわれすぎず、「つく」という言葉の幅広い含意も踏まえつつ憑霊現象をとらえなおした小松和彦の研究[11]などがある[3]。

「憑依」という用語と分類の恣意性[編集]

ただし、学術的な研究が進むにつれて、当初は明確な輪郭をもっているように思われた「憑依」という概念が、実は何が「憑依」で何が「憑依」でないか線引き自体が困難な問題として議論された。宗教学者ミルチャ・エリアーデは「脱魂」であると分類をもうけた。

こうした研究が進む中で、憑依を評価する側の価値判断や政治的判断が色濃く反映され、バイアスがかかってしまっている、やっかいな概念である、ということが次第に認識されるようになってきた[12][3]。

例えば大和言葉の「つく」という言葉ならば、「今日はツイている」のように幸運などの良い意味で用いることができる。ところが「憑依」は否定的な表現である[3]。英語の be obsessed や be possessed などは否定的な表現であり、「憑依」も否定的に用いられる。[3]。現実に起きていることはほぼ類似の現象であっても、書き手の側の価値判断や政治的判断によってそれを呼ぶ表現が恣意的に選ばれてしまい、別の解釈をもたらすと指摘する研究者もいる[3]。

例えば聖書には次のようなくだりがある[3]。

イエスはバプテスマを受けると、すぐに水から上がられた。すると、天が開け、神の御霊が鳩のように自分の上に下ってくるのをご覧になった。また天から声があって言った。「これはわたしの愛する子、わたしの心にかなう者である(マタイによる福音書 3.16)[3]

祈りが終わると、彼らが集まっていた場所が揺れ動き、皆、聖霊に満たされて、大胆に神の言葉を語りだした。(使徒行伝 4.31)[3]

このような箇所が翻訳される場合は肯定的に表現され、「憑依」を暗示するような訳語は使われず、このような箇所は「憑依」に分類されてこなかったのである[3]。一方、同じく聖書には次のようなくだりがある[3]。

イエスが向こう岸のガダラ人の地に着かれると、悪霊に取りつかれた者がふたり、墓場から出てきてイエスのところにやって来た。二人は非常に凶暴で(中略)、突然叫んだ。「神の子、かまわないでくれ。まだ時ではないのに、ここにきて、我々を苦しめるのか」。はるか離れたところで多くの豚の群れがえさをあさっていた。そこで悪霊たちはイエスに願って言った。「もし我々を追い出すのなら、あの豚の中にやってくれ」。イエスが「行け」と言われると、悪霊どもは二人から出て、豚の中に入った。すると豚の群れは崖から海へなだれこみ、水の中で死んだ。豚飼いたちは逃げ出し、町に行き、悪霊に取りつかれた者のことなど一切を知らせた。(マタイによる福音書 8.28-33)[3]

これなどは「取りつかれた」などの「憑依」を暗示する用語・訳語が選ばれ、そういう位置づけになっている[3]。

一方、沖縄のユタと呼ばれる人がカミダーリィの時期を回想した体験談に次のようなものがある[3]。

そして神様に歩かされて、夜中の3時になるといつもウタキまで歩かされて、そうすると、天が開いたように光がさして、昔の(琉球王朝の)お役人のような立派な着物を着たおじいさんが降りて来られて「わたしの可愛いクァンマガ(子孫)」とお話をされる[3]。

この体験談を聖書の引用と比較してみると、明らかにイエス自身の事跡を示したマタイによる福音書3.16以下のくだりと酷似している[3]。まともに判断すれば、マタイによる福音書3.16のくだりと同じ位置づけで研究されてもよさそうなはずのものなのだが、ところが学術の世界では「ユタと言えばカミダーリィ(神がかり)。だからシャーマン。巫者。だから“憑依”される人物だ」といったような、冷静に検討すれば、あまり正しいとは言えない理屈で分類されるようなことが行われてきたのである[3]。

キリスト教徒のなかには、「キリスト教徒以外の異教徒はすべてサタンによって欺かれている」などと言う人もおり[3]、キリスト教の外にあるイタコやユタなどは“悪霊に憑かれた者”に分類し、それに対して、キリスト教の中にある聖霊に関しては「憑かれる」とは表現しないという指摘もある[3]。すなわち、こうした表現や用語の選定段階には、聖書の編者たちやキリスト教徒たちの価値判断や解釈が埋め込まれてしまっているのである。学者らがこうしたキリスト教徒の「信仰」自体を批判する筋合いにはないが[3]、問題なのは、こうしたキリスト教信仰による分類法が、「学術研究」とされてきたものの中にまでも実は深く入り込み、研究領域が恣意的に分けられてしまうようなことが行われてきたことにある[3][13]。つまり、「ついた」「神がかった」などという表現があると「憑依」や「シャーマニズム」に分類して、宗教人類学や宗教民俗学の守備範囲だとし研究されたのに、「(イエス・キリストは)天が開け神の御霊が鳩のように自分の上に下ってくるのをご覧になった」という記述や「高僧に仏の示現があった」「見仏の体験を得た」という記述は、別扱いになってしまい、キリスト教研究や仏教研究の領域で行われる、ということが平然と行われてきてしまったのである[3]。

古代ギリシャ[編集]

哲学[編集]

『饗宴』などのプラトンの著作によれば、神が擬人化される以前から存在したダイモーンという神性の存在が、神と人間のあいだを結合するために憑依という形で個人の人生に介入してくるという[14]。プラトンの師であるソクラテスは頻繁に強度のトランス状態となり、人知を超えたな叡知を授けられたという。プラトンの弁によれば、ソクラテスは「ぼくはいわゆる人間の理知によって語っているではないのです。むしろ、なにか神霊のような、自分ではないある高いものが、ぼくをつき動かしているのです」と語っている[14]。アルキビアデスは、ソクラテスの話を聞くと誰もが強い衝撃を与えられ、神がかった状態に陥ったと述べている。

『パイドロス』の中では「神に憑かれて得られる予言の力を用いて、まさに来ようとしている運命に備えるための、正しい道を教えた人たち」と、前4世紀当時のギリシャの憑依現象について紹介している。『ティマイオス』では、憑依された人が口にする予言や詩の内容を、客観的な視点から理性を用いて的確に判断し解釈する人が傍らに必要であることを述べている。

弁証法やイデア論など、ソクラテスからアリストテレスに連なる哲学には、しばしば非人間的な超越存在が根底に現れる。その起点には、人間の知性を越えたダイモーンの介入による神充状態を理想とし、自らの知や活動の源泉としたソクラテスの教えがある[14]。

アブラハムの宗教[編集]

詳細は「ヘブライ語聖書における魔術と占術」を参照

出エジプト記、レビ記、申命記には、さまざまな魔術や占いを禁止する法律が記されている。その中には次のようなものがある。レビ記19:26 - あなたは...魔術を使ってはならないし、占いをしてもならない

レビ記20:27 - 霊媒師あるいは占いをするものは、必ず死刑に処される

申命記18:10-11 - あなたがたの間には占いをする者、卜者、易者、呪術師、霊媒師、巫(神おろしをするもの)などがいてはならない

アン・ジェファースによれば、霊媒術(神霊や死者の霊を呼び出す術)を禁じる法律が存在することは、イスラエルの歴史を通じて呪術、神降ろし等を行う霊媒術が問題を起こしていたことを証明している[15]。

アブラハムの宗教であるユダヤ教もキリスト教もイスラム教にも、預言者が登場する。これは神が宿ったものともいえる(預言、福音、啓示)[要出典]。

キリスト教[編集]

新約聖書の福音書で「つかれた」と訳されるδαιμονίζομαιという語は、パウロ書簡にはでてこない[16][17]。

ルーダンの憑依事件(英語版)[18]について、神学者のミッシェル・セルトーが、神学、精神分析学、社会学、文化人類学をクロスオーバーさせつつ分析している[19]。

カトリック教会の神学では、夢遊病的なもの(the somnambulic)の型のつきものに possession の名を与え、正気のもの(the lucid)の型のつきものに obsession の名を与えている[20]。

日本[編集]

神道・古神道[編集]

この節は検証可能な参考文献や出典が全く示されていないか、不十分です。出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。(このテンプレートの使い方)

出典検索?: "憑依" – ニュース · 書籍 · スカラー · CiNii · J-STAGE · NDL · dlib.jp · ジャパンサーチ · TWL(2011年2月)

大相撲も、皇室に奉納される神事であり、横綱はそのときの「戦いの神」の宿る御霊代である。昔の巫女は1週間程度水垢離をとりながら祈祷を行うことで、自分に憑いた霊を祓い浄める「サバキ」の行をおこなうこともあった。

沖縄[編集]

沖縄では「ターリ」あるいは「フリ」「カカイ」などと呼ばれる憑依現象は、その一部が「聖なる狂気」として人々から神聖視された。そのおかげで憑依者は、治療される対象として病院に隔離・監禁すべきとする近代西洋的思考に絡め取られることは免れた[21]、ともされる。

沖縄の本土復帰以降には、同地に精神病院が設立されたものの、同じころ(西洋的思考の)精神医学でも「カミダーリ」なども、人間の示す積極的な営為の一つであるというように肯定的な見方もなされるようになったおかげで、沖縄は憑依(の一部)を肯定する社会、として現在まで存続している[22]ともされている。

日本語における憑依の別名[編集]神宿り - 和御魂の状態の神霊が宿っている時に使われる。

神降ろし - 神を宿すための儀式をさす場合が多い。「神降ろしを行って神を宿した」などと使われる。降ろす神によって、夷下ろし、稲荷下ろしと称される[23]。能管のヒシギと呼ばれる甲高い音は「神降ろしの音」と呼ばれ、神道の儀式で神降ろしに使われた岩笛から発達したさとれる[24]。新潟県の葛塚まつりでは、笛は神降ろしの笛と言われて演奏者は尊重され、吹き手以外笛に触れない[25]

神懸り - 主に「人」に対し、和御魂の状態の神霊が宿った時に使われる。

憑き物 - 人や動物や器物(道具)に、荒御魂の状態の神霊や、位の低い神である妖怪や九十九神や貧乏神や疫病神が宿った時や、悪霊といわれる怨霊や生霊がこれらのものに宿った時など、相対的に良くない状態の神霊の憑依をさす。

ヨリマシ -尸童と書かれる。祭礼に関する語で、稚児など神霊を降ろし託宣を垂れる資格のある少年少女がそう称された。尚柳田國男は『先祖の話』中で憑依に「ヨリマシ」のふりがなを当てている[26]。

民俗学における憑依観[編集]

民俗学者の小松和彦は、憑き物がファースの定義による「個人が忘我状態になる」状態を伴わないことや、社会学者I・M・ルイスの「憑依された者に意識がある場合もある」という指摘以外も含まれることから、憑依を、フェティシズムという観念からなる宗教や民間信仰において、マナによる物体への過剰な付着を指すとした。そのため、「ゲームの最中に回ってくる幸運を指すツキ」の範疇まで含まれると定義する。さらに、そのような観点から鑑みるに、日本のいわゆる憑きもの筋は「possession ではなく、過剰さを表す印である stigma」であるとする[27]。また、谷川健一は、「狐憑き」が「スイカツラ」や「トウビョウ」など、蛇を連想させる植物でも言われることから、「蛇信仰の名残」とし、「狐が憑いた」という説明を「後に説明しなおされたもの」と解説している[28]。

神秘主義における憑依観[編集]

この節の出典は、Wikipedia:信頼できる情報源に合致していないおそれがあります。そのガイドラインに合致しているか確認し、必要であれば改善して下さい。(2011年2月)

職業霊媒のように、人間が意図的に霊を乗り移らせる場合もある[2]。だが、霊が一方的に人間に憑くものも多く、しかも本人がそれに気がつかない場合が多い[2]。とりつくのは、本人やその家族に恨みなどを持つ人の霊や、動物霊などとされる[2]。

何らかのメッセージを伝えるために憑くとされている場合もあり、あるいは本人の人格を抑えて霊の人格のほうが前面に出て別人になったり、動物霊が憑依した場合は行動や容貌がその動物に似てくる場合もある[2]。

こうした憑依霊が様々な害悪を起こすと考えられる場合は、それは霊障と呼ばれている[2]。

ピクネットによる説明[編集]

超常現象、オカルト、歴史ミステリー専門の作家、研究者、講演者であるピクネットは、種々の文献や、証言を調査して以下のように紹介している。歴史憑依は太古の昔から現代まで、また洋の東西を問わず見られる。すでに人類の歴史の初期段階から、トランス状態に入り、有意義な情報を得ることができるらしい人がわずかながらいることほ知られていた。部族社会が出現しはじめた頃、憑依状態になった人たちはいつもとは違う声で発語し、周囲の人々は霊が一時的に乗り移った気配を感じていたようであるとピクネットは主張した[29]。初期文明では憑依は「神の介入」と見なされていたが、古代ギリシャのヒポクラテスは「憑依は、他の身体的疾患と同様、神の行為ではない」と異議を唱えている[29]。ピクネットによると、西洋のキリスト教では、憑依に対する見解は時代とともに変化が見られ、聖霊がとりつくことが好意的に評価されたり、中世には魔法使いや異端と見なされ迫害されたり、近代でも悪魔祓いの対象とされたりした。現在でも憑依についての解釈は宗派によって、見解の相違が存在する[29]。(→#キリスト教)近年でも憑依の典型的な例は起きている。例えばイヴリン・ウォーは『ギルバート・ピンフォードの苦行』という本を書いたが、これは小説の形で提示されてはいるものの、ウォー自身は、これは自分に実際に起きたこと、とテレビで述べている(ただしこの事例では、酒と治療薬の組み合わせが原因とも言われている)[29]。最近では「良い憑依」というのを信じる人々もいる。肉体を備えていない霊が、肉体の「主人」の許可を得てウォークイン状態で入り込み、祝福のうちに主人にとってかわることもあり得る、と信じる人たちがいる[29]。古代イスラエルヘブライ語聖書(旧約聖書)にも憑依の記述は存在する。古代イスラエルでは、その状態は霊に乗っ取られた状態であり、乗っ取る霊は悪い霊のこともあり、サタンの代理として登場する記述がある[要検証 – ノート][29]。キリスト教ピクネットは初期のキリスト教徒は憑依を次のように好意的に見なしているとした。「聖パウロにおいて、病気の治癒、予言、その他の奇跡を約束して下さった聖霊が憑くような現象は、きわめて望ましい。」[要検証 – ノート][29]その一方で、ピクネットは憑依に関連する能力として「霊の見分け」(つまり悪霊を見破る能力)が認められていたとした[29]。時代が下ると憑依を悪霊のしわざとする考え方が一般的になり、憑依状態の人が語る内容がキリスト教の正統教義に一致しない場合は目の敵にされ、そこまでいかない場合でも、憑依は悪魔祓いの対象とされている。憑依状態になる人が、魔法使い、あるいは異端者として迫害される事例が多くなっていった[29]。ピクネットは、憑依の歴史的記録で、証拠文献が豊富な例として、1630年代のフランスのルーダンで起きた「尼僧集団憑依」事件をとりあげている[29]。この事件では、尼僧たちの悪魔祓いを行うために修道士シュランが派遣されたのだが、そのシュラン自身も憑依されてしまった。尼僧ジャンヌも修道士シュランも、後に口を揃えてこう言った。「卑猥な言葉や神をあざける言葉を口にしながら、それを眺め耳を傾けているもうひとりの自分がいた。しかも口から出る言葉を止めることができない。奇怪な体験だった。[29]」(ピクネットの引用)A.K.エステルライヒが1921年の著書『憑依』で示した、憑依の中には、悪魔が発語するような語り口、性格が異なる悪霊が五つも六つも詰めかけているような様子、乗り移られるたびに別人になったかのように見えるものも含まれていたとピクネットは記述した[29]。ピクネットはカトリック教徒の中の実践的な人々の間では、「憑依は悪魔のしわざ」説は次第に説得力を失ったが、英国国教会は今でも悪魔祓いを専門とする牧師団は存在しているとした[29]。医学領域や心理学の領域で、憑依を二重人格あるいは多重人格の表れとみなす考え方は多い[29]。「『自分』というのは単一ではない。複数の自分の寄せ集めで普段はそれが一致して動いている。あるいは、日々の管理を筆頭格のそれに委ねている。」ピクネットはこれに対し、この説明の例では、霊媒行為について当てはまらない、霊媒行為の場合、「筆頭格」のそれは、明らかに何か異なる実在のように見えることが多く、また霊媒はトランス状態になると、その人が通常の状態ならば絶対に知っているはずのない情報を提供していると主張する[29]。

文学に描かれた憑依[編集]「アクセス」 - 誉田哲也の小説

「白狐魔記」 - 斎藤洋の小説

脚注[編集]

^ a b 『広辞苑』第四版、第五版

^ a b c d e f g 羽仁礼『超常現象大事典』成甲書房、2001年、76頁。ISBN 978-4880861159。

^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x 池上良正「第五章」『死者の救済史: 供養と憑依の宗教学』角川学芸出版、2003年、157-194頁。ISBN 4047033545。

^ Daher, Jorge Cecílio Jr; Damiano, Rodolfo Furlan; Lucchetti, Alessandra Lamas Granero; Moreira-Almeida, Alexander; Lucchetti, Giancarlo (2017-01). “Research on Experiences Related to the Possibility of Consciousness Beyond the Brain: A Bibliometric Analysis of Global Scientific Output” (英語). The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 205 (1): 37. doi:10.1097/NMD.0000000000000625. ISSN 0022-3018.

^ 日本テレビ「謎の憑依現象を追え!」(ウェイバックマシン)

^ Hecker, Tobias; Braitmayer, Lars; van Duijl, Marjolein (2015-12-01). “Global mental health and trauma exposure: the current evidence for the relationship between traumatic experiences and spirit possession” (英語). European Journal of Psychotraumatology 6 (1). doi:10.3402/ejpt.v6.29126. ISSN 2000-8066. PMC PMC4654771. PMID 26589259.

^ 『宗教学辞典』555頁、東京大学出版会 (1973/01) ISBN 9784130100274

^ 『宗教学辞典』249頁 - 250頁、東京大学出版会 (1973/01) ISBN 9784130100274

^ a b p.159

^ 秋葉降『朝鮮巫俗の現地研究』

^ 『憑霊信仰論』伝統と現代社、1982年

^ 川村邦光『憑依の視座』青弓社、1997年

^ p.167

^ a b c 古東哲明『現代思想としてのギリシア哲学』 <講談社選書メチエ> 講談社 1998年 ISBN 4062581272 pp.136-148.

^ Jeffers, Ann (1996). Magic and Divination in Ancient Palestine and Syria. Brill. p. 181

^ 山崎ランサム和彦『平和の神の勝利』プレイズ出版 p.47

^ 『聖書語句大辞典』教文館

^ オルダス・ハックスリーが『ルーダンの悪魔』 - The Devils of Loudun (1952)を書き、これを原作にケン・ラッセル監督が『肉体の悪魔』(1971)として映画化。同じ事件はヤロスワフ・イヴァシュキェヴィッチ『尼僧ヨアンナ』(岩波文庫)などにも描かれていて、イェジー・カヴァレロヴィチが同名の映画化(1961)。

^ ミシェル・ド・セルトー『ルーダンの憑依』みすず書房 2008。原書はMichel de CERTEAU, LA POSSESSION DE L’OUDUN. PARIS, JULLIARD, 1970.

^ 『宗教学辞典』419頁、東京大学出版会 (1973/01) ISBN 9784130100274

^ 塩月亮子「憑依を肯定する社会 : 沖縄の精神医療史とシャーマニズム(憑依の近代とポリティクス,自由テーマパネル,<特集>第六十四回学術大会紀要)」『宗教研究』第79巻第4号、日本宗教学会、2006年、1035-1036頁、doi:10.20716/rsjars.79.4_1035、ISSN 0387-3293、NAID 110004752051。

^ 塩月亮子 同上

^ 定本柳田國男集9巻 247頁

^ 笛「ヒシギ」洗足学園音楽大学伝統音楽デジタルライブラリー

^ 会報『さえずり』平成24年2号(平成24年10月13日発行)祭り囃子が聞こえる新潟県リコーダー教育研究会

^ 定本柳田國男集10巻 137頁

^ 小松和彦『憑霊信仰論』30頁 伝統と現代社 1982年

^ 『魔の系譜』『谷川健一著作集1』三一書房。29頁 書中で引用される石塚尊俊の『日本の憑き物』では犬神の一種として吸葛(スヒカツラ)が出る。

^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o リン・ピクネット『超常現象の事典』青土社、1994年、220-222頁。ISBN 978-4791753079。

参考文献[編集]池上良正『死者の救済史 : 供養と憑依の宗教学』角川書店〈角川選書〉、2003年。ISBN 4-04-703354-5。

リン・ピクネット 著、関口篤 訳『超常現象の事典』青土社、1994年。ISBN 4-7917-5307-0。

羽仁礼『超常現象大事典 : 永久保存版』成甲書房、2001年、76頁。ISBN 4-88086-115-4。

花渕馨也『精霊の子供 : コモロ諸島における憑依の民族誌』春風社、2005年。ISBN 4-86110-031-3。

関連項目[編集]神託 - 神降ろしによる神や霊魂の啓示や予言巫/巫女 - ふ、かんなぎ

ウィジャボード/オートマティスム

生霊/イタコお祓い/審神者

憑きもの筋獣憑き/管狐/犬神/オサキ - 日本に分布する憑き物の伝承

悪魔憑き/悪魔払い/悪霊ばらい - 悪魔憑きの対処方法

解離性同一性障害

解離性障害

解離 (心理学)

催眠/暗示

森田正馬 - 森田療法で有名。祈祷性精神病を研究した。

外部リンク[編集]岡田靖雄「憑きものの現象論 - その構造分析 - (上)」『日本医史学雑誌』第44巻第1号、日本医史学会、1998年3月、3-25頁、ISSN 05493323、NAID 10006591976。

岡田靖雄「憑きものの現象論 - その構造分析 - (下)」『日本医史学雑誌』第44巻第3号、日本医史学会、1998年9月、369-384頁、ISSN 05493323、NAID 10006592109。

酒井貴広「現在までの憑きもの研究とその問題点 : 憑きもの研究の新たなる視座獲得に向けて」『早稲田大学大学院文学研究科紀要. 第4分冊』第59巻、早稲田大学大学院文学研究科、2013年、123-140頁、ISSN 1341-7541、NAID 120005430682。

大宮司信「日本における憑依研究の一側面-精神医学の視点から-」『北翔大学北方圏学術情報センター年報』第6号、北翔大学北方圏学術情報センター、2014年、1-6頁、ISSN 2185-3096、NAID 120005569010。

石井美保「接触領域における憑依、接触領域としての憑依 : ガーナの神霊祭祀を事例として」『コンタクト・ゾーン』第1号、京都大学人文科学研究所人文学国際研究センター、2007年3月、116-129頁、NAID 120005307096。

『薛公瓚傳(ソルゴンチャンジョン)』と韓国の憑依譚高永爛、国際日本文化研究センター『怪異・妖怪文化の伝統と創造──ウチとソトの視点から』, 2015.1.30

隠す

典拠管理データベース

全般

FAST

国立図書館

スペイン

フランス

BnF data

ドイツ

イスラエル

アメリカ

日本

その他

IdRef 2

カテゴリ: 憑き物

シャーマニズム

心霊現象

TSF

宗教の心理学

神経科学

意識研究

意識

===

목차 표시/숨기기 전환

빙의

26개의 언어 버전

페이지

노트

브라우징

편집

기록 표시

도구

출처 : 무료 백과 사전 "Wikipedia (Wikipedia)"

憑依(효이)는 영 등이 넘어가는 것 [1] [2] .憑(つ)く[1] . 빙령 [3] , 신강하 , 신 현 , 신주쿠 , 빙물 이라고도 한다. 붙잡는 영의 종류에 따라서는, 악마 빙 , 여우 등이라고 부르는 경우도 있다 [2] . 현대에서도 뇌로부터 독립한 의식의 존재로서 빙의 현상의 보고가 연구되고 있으며, 최근에는 그러한 뇌로부터 독립된 의식의 존재를 보고하는 총설도 늘어나 본격적인 학문 분야가 되고 있다 [4] . 의학의 세계에서는 빙의가 정신질환의 일종으로 간주될 수도 있지만 [5] , 빙의는 의식장에서의 빙의와 정신질환에 의한 빙의로 분류되며 반드시 정신질환으로는 한정되지 않는다 [6] . 종교학에서는 " 붙어있는 것"을 "일부의 영력이 빙의하여 인간의 정신 상태와 운명에 극적인 영향을 미친다는 신념"이라고 한다 .

「빙의」라는 표현은, 독일어의 Besessenheit 나 영어의 (spirit) possession 등의 학술어를 번역하기 위해, 쇼 와경, 특히 제2차 세계 대전 후부터 이용되게 된 것으로 추정되고 있다( 아래의 " 역어의 역사 "를 참조). 퍼스(Firth, R)에 의하면, 「( 샤머니즘 에 있어서의) 빙의(빙령)는 트랜스 의 한 형태이며, 통상 어느 인물에 외재하는 영이 가르침의 행동을 지배하고 있는 증거」라고 자리매김된다. 탈혼 ( 영 : ecstasy 혹은 soul loss )이나 빙의( 영 : possession )는 트랜스 상태 에서의 접촉·교통의 형태이다 [8] .

번역어의 역사 [ 편집 ]

인류학 , 종교학 , 민속학 등의 학술 용어 로 사용되게 된 '빙의' 혹은 '빙령'이라는 표현은 분명히 독일어의 Besessenheit 이나 영어의 ( spirit ) possession 등의 번역어이며, 구미의 학자들이 사용하는 학술 용어가 일본의 학계에 수입된 것이라고 이케가미 료쇼 는 지적했다 [9] . 1941년(쇼와 25년)이 있는 학술문헌 [10] 에는 「빙의」라는 단어가 등장했다. 일반화 된 것은 제 2 차 세계 대전 후일 것으로 추정된다 [3] [9] .

"빙의"라는 학술 용어가 사용되고 나서,이 용어에 관해서, 다양한 이론화 및 유형화가 이루어져 왔다 [3] . 예를 들면, 빙의라는 용어에 지나치게 얽매이지 않고, 「붙는다」라는 말의 폭넓은 함의도 근거로 하면서 빙령 현상을 파악한 고마쓰 카즈히코 의 연구 [11] 등이 있다 [3] .

'빙의'라는 용어와 분류의 자의성 [ 편집 ]

다만, 학술적인 연구가 진행됨에 따라 당초에는 명확한 윤곽을 갖고 있는 것처럼 보였던 '빙의'라는 개념이 실은 무엇이 '빙의'이고 무엇이 '빙의'가 아닌가 선취 자체가 어려운 문제로 논의되었다. 종교학자 밀차 엘리에 데는 '탈혼'이라고 분류를 벌었다.

이러한 연구가 진행되고 있는 가운데, 빙의를 평가하는 측의 가치 판단이나 정치적 판단이 짙게 반영되어, 바이어스가 걸려 버리고 있는, 힘든 개념이다, 라고 하는 것이 점차 인식되게 되어 왔다 [12] [3] .

예를 들어 야마토 단어 의 "붙는다"라는 말이라면, "오늘은 트위어있다"와 같이 행운 등의 좋은 의미로 사용할 수 있다. 그런데 '빙의'는 부정적인 표현이다 [3] . 영어의 be obsessed 나 be possessed 등은 부정적인 표현이며, 「빙의」도 부정적으로 사용된다. [3] . 현실에서 일어나고 있는 것은 거의 유사한 현상이라도, 필자의 측의 가치 판단이나 정치적 판단에 의해 그것을 부르는 표현이 자의적으로 선택되어 버려, 다른 해석을 가져온다고 지적하는 연구자 또한 [3] .

예를 들어, 성경 에는 다음과 같이 속이 있다 [3] .

예수님은 침례를 받자마자 물에서 올라갔습니다. 그러자 하늘이 열리고 하나님의 영이 비둘기 처럼 자신 위에 내려오는 것을 보게 되었다 . 또 하늘에서 목소리가 있어 말했다. "이것은 내 사랑하는 아들, 내 마음에 걸린 사람이다 ( 마태복음 3.16) [3]

기도가 끝나자 그들이 모여 있던 곳이 흔들리고, 모두 성령 으로 가득 채워 대담하게 하나님의 말씀을 들었다 . ( 사도행전 4.31) [3]

이러한 개소가 번역되는 경우는 긍정적으로 표현되어 '빙의'를 암시하는 번역어는 사용되지 않고, 이러한 개소는 '빙의'로 분류되지 않았던 것이다 [3] . 한편, 마찬가지로 성경에는 다음과 같지 않다 [3] .

예수님이 건너편의 가다라인 땅에 도착하자 악령에 사로잡힌 자들이 두 묘지에서 나와 예수님께로 왔다. 두 사람은 매우 흉포하고 (중략) 갑자기 외쳤다. "하느님의 아들, 상관하지 말아줘. 아직 시간이 아닌데 여기에 와서 우리를 괴롭히는가?" 훨씬 먼 곳에서 많은 돼지의 무리가 먹이를 먹었다. 거기서 악령들은 예수께 바라며 말했다. "만약 우리를 쫓는다면, 그 돼지 안에 해줘." 예수께서 “가라”고 말하자, 악령들은 두 사람을 떠나 돼지 안으로 들어갔다. 그러자 돼지의 무리는 절벽에서 바다로 달려들어 물속에서 죽었다. 돼지고기들은 도망쳐 마을에 가서 악령에 사로잡힌 자 등 일절을 알렸다. ( 마태복음 8.28-33) [3]

이것 등은 「취해졌다」등의 「빙의」를 암시하는 용어·역어가 선택되어, 그러한 위치설정이 되고 있다 [3] .

한편, 오키나와의 유타 라고 불리는 사람이 카미다리의 시기를 회상한 체험담에 다음과 같은 것이 있다 [3] .

그리고 하나님 께 걸어가고 밤중 3시가 되면 항상 우타키까지 걸어서 그렇게 하면 하늘이 열린 것처럼 빛이 나서 옛날의 류큐 왕조의 장교와 같은 훌륭한 기모노를 입은 할아버지 가 내려와서 "나의 귀여운 광마가(후손)"라고 이야기를 한다 [3] .

이 체험담을 성경의 인용과 비교해 보면, 분명히 예수 자신의 사적을 나타낸 마태복음 3.16 이하의 몫과 닮았다 [3] . 제대로 판단하면, 마태복음 3.16의 구두와 같은 위치에서 연구되어도 좋을 것 같은 것이지만, 그런데 학술의 세계에서는 「유타라고 하면 카미다리(신가카리).그러니까 샤먼.무자. 그러므로 “빙의”되는 인물이다”와 같은 냉정하게 검토하면 그다지 옳다고는 말할 수 없는 이굴로 분류되는 일이 이루어져 온 것이다 [3] .

그리스도인 들 가운데는 “기독교인 이외의 이교도는 모두 사탄에 의해 속이고 있다”라고 말하는 사람도 있어 [3] , 기독교 밖에 있는 이타코와 유타 등은 “악령에 움푹 패인 자”로 분류해 그에 대해 기독교 안에 있는 성령 에 관해서는 '빙빙'이라고 표현하지 않는다는 지적도 있다 [3] . 즉, 이러한 표현이나 용어의 선정 단계에는 성경의 편자들과 기독교인들의 가치 판단 과 해석이 내장 되어 버린 것이다. 학자들이 이러한 기독교인의 '신앙' 자체를 비판하는 근육에는 없지만 [3] , 문제인 것은 이러한 기독교 신앙에 의한 분류법이 '학술연구'로 여겨져 온 것 중에까지도 실은 깊게 들어가 , 연구 영역이 자의적으로 나뉘어 버리는 것과 같은 일이 이루어져 온 것에 있다 [3] [13] . 즉, 「붙었다」「신이 있었다」라고 하는 표현이 있으면 「빙의」나 「샤머니즘」으로 분류해, 종교 인류학이나 종교 민속학의 수비 범위라고 해 연구되었는데, 「(예수・그리스도는) 하늘이 열리고 하나님의 성령이 비둘기처럼 자신 위에 내려오는 것을 보았다. '라는 설명은 별도로 다루어져 기독교 연구와 불교 연구의 영역에서 이루어지는 것이 평연하게 이루어져 버린 것이다 [3] .

고대 그리스 [ 편집 ]

철학 [ 편집 ]

" 향연 "등의 플라톤 의 저작에 의하면, 신이 의인화되기 이전부터 존재한 다이몬 이라는 신성의 존재가, 신과 인간의 사이를 결합하기 위해 빙의라는 형태로 개인의 인생에 개입하고 온다는 [14] . 플라톤의 스승인 소크라테스 는 자주 강도의 트랜스 상태가 되어, 인지를 넘은 지혜를 받았다고 한다. 플라톤의 밸브에 따르면, 소크라테스는 "나는 이른바 인간의 이지에 의해 말하고 있는 것은 아니다. 오히려, 무엇인가 신령과 같은, 자신이 아닌 어느 높은 것이, 나를 따라 움직이고 있는 것입니다" 말한다 [14] . 아르키비아데스 는 소크라테스의 이야기를 들으면 모두가 강한 충격을 받고 하나님이 걸린 상태에 빠졌다고 말한다.

『파이드로스』 중에서는 「하느님께 빙빙 얻어지는 예언의 힘을 이용하여 바로 오려고 하는 운명에 대비하기 위한 올바른 길을 가르친 사람들」이라고 전 4세기 당시 그리스의 빙의 현상 소개합니다. ' 티마이오스 '에서는 빙의받은 사람이 입으로 하는 예언이나 시의 내용을 객관적인 관점에서 이성을 이용하여 정확하게 판단하고 해석 하는 사람이 옆에 필요하다고 말하고 있다.

변증법 이나 아이디어론 등 소크라테스에서 아리스토텔레스 로 이어지는 철학에는 종종 비인간적인 초월 존재가 근본적으로 나타난다. 그 기점에는, 인간의 지성을 넘은 다이몬의 개입에 의한 신충 상태를 이상으로 하고, 스스로의 지나 활동의 원천으로 한 소크라테스의 가르침이 있다 [14] .

아브라함의 종교 [ 편집 ]

자세한 내용은 " 히브리어 성경에서 마술과 점술 "을 참조하십시오.

출애굽기 , 레위기 , 신명기 에는 다양한 마법 과 점을 금지하는 법률이 적혀 있다. 그 중에는 다음과 같은 것이 있다.레위기 19:26 - 당신은... 마법을 사용해서는 안 되고

레위기 20:27 - 영매사 또는 운세를 하는 것은 반드시 사형에 처함

신명기 18:10-11 - 너희들 사이에는 운세를 하는 자, 추종자, 이주자 , 주술사 , 영 매사 , 무 (하느님을 내리는 것) 등이 없어야 한다.

안 제퍼스에 의하면, 영매술 (신령이나 죽은 자의 영을 불러오는 수술)을 금지하는 법률이 존재하는 것은, 이스라엘의 역사를 통해서 주술, 신강하 등을 실시하는 영매술 이 문제를 일으키고 있었다는 것을 증명하고 있다 [15] .

아브라함의 종교인 유대교도 기독교 도 이슬람교 에도 선지자 가 등장 한다. 이것은 하나님이 머물렀다고도 할 수 있다( 예언 , 복음 , 계시 ) [ 요출전 ] .

기독교 [ 편집 ]

신약성경 의 복음서에서 “붙여졌다”고 번역되는 δαιμονίζομαι 라는 말은 바울 서한 에는 나오지 않는다 [16] [17] .

루단의 빙의 사건 ( 영어판 ) [18] 에 대해 신학자 미셸 셀토 가 신학 , 정신 분석학 , 사회학 , 문화 인류학 을 크로스 오버하면서 분석하고있다 [19] .

가톨릭 교회 의 신학에서는 몽유병적인 것( the somnambulic )의 형태의 붙은 것에 possession 의 이름을 주고, 정기적인 것 ( the lucid )의 형태의 붙은 것에 obsession 의 이름을 주고 있다 [20] .

일본 [ 편집 ]

신도·고신도 [ 편집 ]

이 절은 검증 가능한 참고 문헌이나 출처 가 전혀 나타나지 않았거나 불충분합니다. 출처를 추가 하여 기사의 신뢰성 향상에 도움을 주세요. ( 이 템플릿 의 사용법 ) 출처

검색 ? : " 빙의 " – 뉴스 · 책 · 스칼라 · CiNii

스모 도 황실 에 봉납 되는 신사이며, 요코즈나 는 그 때의 「싸움의 신」이 머무는 성령이다. 옛 무녀는 1주일 정도 물을 떼어내면서 기도를 하는 것으로, 자신에게 빙한 영을 섬기는 ‘사바키’의 행을 행하기도 했다.

오키나와 [ 편집 ]

오키나와에서는 '타리' 혹은 '후리' '카카이' 등으로 불리는 빙의 현상은 그 일부가 '거룩한 광기'로 사람들로부터 신성시되었다. 그 덕분에 빙의자는 치료받는 대상으로서 병원에 격리·감금해야 하는 근대서양적 사고에 얽매이는 것은 면했다 [21] 라고도 한다.

오키나와의 본토 복귀 이후에는 동지에 정신 병원이 설립되었지만, 같은 시기에 (서양적 사고의) 정신 의학에서도 「카미다리」등도 인간이 나타내는 적극적인 영위의 하나라고 에 긍정적인 견해도 이뤄진 덕분에 오키나와는 빙의(의 일부)를 긍정하는 사회로서 현재까지 존속하고 있다 [22] 라고도 한다.

일본어의 빙의 별명 [ 편집 ]신주쿠 - 일본어 영혼 상태의 신령이 머무르고 있을 때 사용된다.

신 강하 - 신을 머물기 위한 의식을 드리는 경우가 많다. 「신강하를 가서 신을 묵었다」등으로 사용된다. 내리는 신에 의해, 욕을 내리고, 벼 내림이라고 불린다 [23] . 능관 의 히시기라고 불리는 갑높은 소리는 「신강하의 소리」라고 불리며, 신도의 의식에서 신강하에 사용된 바위피리로부터 발달된 사냥된다 [24] . 니가타현의 가쓰라즈카 축제 에서는, 휘파람은 신강의 피리라고 불려 연주자는 존중되고, 불어 이외의 피리를 만지지 않는다 [25]

하나님의 마음 - 주로 '사람'에 대해 화어혼의 상태의 신령이 머무를 때 사용된다.

빙물 - 사람이나 동물 과 기물(도구)에 황혼 의 상태의 신령이나, 낮은 신인 요괴 나 구주 9신이나 가난신이나 역병신이 머물렀을 때나, 악령 이라고 불리는 원령 이나 생령 이 이들에 머물렀을 때 등 상대적으로 좋지 않은 상태의 신령의 빙의를 말한다.

요리마시 - 범동이라고 쓰인다. 제례에 관한 말로, 치아 등 신령을 내리고 탁선을 처지는 자격이 있는 소년 소녀가 그렇게 칭했다. 나카야나기 쿠니오는 『선조의 이야기』 중 빙의에 「요리마시」의 후리가나를 맞고 있다 [26] .

민속학의 빙의관 [ 편집 ]

민속학자의 고마츠 카즈히코 는 빙물이 퍼스의 정의에 의한 「개인이 망가 상태가 된다」상태를 수반하지 않는 것이나 사회학자 I・M・루이스의 「빙의된 사람에게 의식이 있는 경우도 있다」라고 한다 지적 이외도 포함되기 때문에 빙의를 페티시즘 이라는 관념으로 구성된 종교 와 민간 신앙 에서 마나 에 의한 물체 에의 과도한 부착을 가리킨다고 했다. 그 때문에, 「게임의 중간에 돌아오는 행운을 가리키는 츠키」의 범주까지 포함된다고 정의한다. 또한, 이러한 관점에서 볼 때, 일본의 이른바 빙근 은 " possession 이 아니라 과잉을 나타내는 표시 인 stigma "라고한다 [27] . 또, 타니가와 켄이치 는, 「여우 빙상」이 「수박」이나 「토우비우」등, 뱀을 연상시키는 식물에서도 말해지기 때문에, 「뱀 신앙의 명잔」이라고 해, 「여우가 빙빙했다」라고 하는 설명을 「후에 설명 다시 한 번 "라고 해설하고있다 [28] .

신비주의의 빙의관 [ 편집 ]

이 섹션의 출처는 Wikipedia : 신뢰할 수있는 출처 와 일치하지 않을 수 있습니다 . 그 지침을 충족하는지 확인하고 필요한 경우 개선하십시오. ( 2011년 2월 )

직업 영매와 같이 인간이 의도적으로 영을 넘어갈 수 있다 [2] . 하지만 영이 일방적으로 인간에게 빙하는 것도 많고, 게다가 본인이 그것에 눈치채지 않는 경우가 많다 [2] . 붙잡는 것은, 본인이나 그 가족에게 원한 등을 가지는 사람의 영이나, 동물령 등으로 된다 [2] .

어떠한 메시지를 전하기 위해서 빙빙으로 여겨지고 있는 경우도 있어, 혹은 본인의 인격을 억제해 영의 인격 쪽이 전면에 나와 별인이 되거나, 동물령이 빙의한 경우는 행동이나 외모가 그 동물 와 유사할 수도 있다 [2] .

이러한 빙의령이 다양한 해악을 일으킨다고 생각된다면 그것은 영장 이라고 불린다 [2] .

피크넷에 의한 설명 [ 편집 ]

초상현상 , 오컬트, 역사 미스터리 전문 작가, 연구자, 강연자인 피크 넷 은 다양한 문헌과 증언을 조사하여 다음과 같이 소개하고 있다.역사빙의는 태고의 옛부터 현대까지, 또 서양 동서를 불문하고 볼 수 있다. 이미 인류의 역사의 초기 단계부터 트랜스 상태 에 들어가, 의미있는 정보를 얻을 수 있는 것 같은 사람이 조금인 것으로 알려져 있었다. 부족사회가 출현하기 시작했을 무렵, 빙의상태가 된 사람들은 평소와는 다른 목소리로 발언했고, 주위 사람들은 영이 일시적으로 넘어간 기색을 느꼈던 것 같다고 픽넷 은 주장 했다 [29] .초기 문명에서는 빙의는 '신의 개입'으로 간주되었지만, 고대 그리스의 히포크라테스 는 '빙의는 다른 신체적 질환과 마찬가지로 신의 행위가 아니다'라고 이의를 제기하고 있다 [29] .피크넷 에 의하면, 서양 기독교에서는 빙의에 대한 견해는 시대와 함께 변화가 보이고, 성령이 취하는 것을 호의적으로 평가되거나, 중세에는 마법사나 이단으로 간주되어 박해되거나 의 대상이 되기도 했다. 현재에도 빙의에 대한 해석은 종파에 의해 견해의 차이가 존재한다 [29] . (→ #기독교 )최근에도 빙의의 전형적인 예는 일어나고 있다. 예를 들어 이브린 워 는 '길버트 핀포드의 고행'이라는 책을 썼는데, 이것은 소설의 형태로 제시되어 있지만, 워 자신은 이것이 자신에게 실제로 일어난 것이라고 TV에서 말한다 (단,이 사례에서는 술과 치료제의 조합이 원인이라고도 알려져있다) [29] .최근에는 '좋은 빙의'라는 것을 믿는 사람들도 있다. 육체를 갖추지 않은 영이 육체의 '주인'의 허가를 얻어 워크인 상태로 들어가 축복 중에 주인에게 있어서 변할 수도 있다고 믿는 사람들이 있다 [29] .고대 이스라엘히브리어 성경 ( 구약 성경 )에도 빙의의 설명은 존재한다. 고대 이스라엘 에서는 그 상태는 영 에 탈취된 상태이며, 탈취하는 영은 나쁜 영이기도 하고, 사탄 의 대리로서 등장하는 기술이 있다 [ 요검증 – 노트 ] [29] .기독교픽넷 은 초기 기독교인들은 빙의를 다음과 같이 호의적으로 보고 있다고 했다.“ 성 바울 에서 질병 의 치유, 예언 , 기타 기적을 약속해 주신 성령 이 희미 해지는 현상 은 매우 바람직하다 . ”한편, 피크넷 은 빙의와 관련된 능력으로서 「영의 구별」(즉 악령을 깨는 능력)이 인정되고 있었다고 했다 [29] .시대가 내려가면 빙의를 악령의 주름으로 하는 사고방식이 일반적이 되어, 빙의 상태의 사람이 말하는 내용이 기독교의 정통교의와 일치하지 않는 경우는 눈의 적이 되고, 거기까지 가지 않을 경우라도 빙의는 악마祓의 대상으로되어있다. 빙의 상태가 되는 사람이, 마법사 , 혹은 이단자 로서 박해 되는 사례가 많아져 갔다 [29] .피크넷 은 빙의의 역사적 기록으로 증거문헌이 풍부한 예로서 1630년대 프랑스 루단에서 일어난 '수녀집단 빙의' 사건을 다루고 있다 [29] . 이 사건에서는 수녀들의 악마를 치르기 위해 수도사 슈란이 파견되었지만, 그 슈란 자신도 빙의되어 버렸다. 수녀 장느도 수도사 슈란도 뒤에 입을 모아 이렇게 말했다.“비추한 말이나 하나님을 비웃는 말을 입으로 하면서, 그것을 바라보고 듣고 있는 또 하나의 자신이 있었다. 게다가 입에서 나오는 말을 멈출 수 없다. 기괴한 체험이었다.[ 29] ” ( 피크넷 인용)AK에스테르라이히가 1921년의 저서 '빙의'로 제시한 빙의 중에는 악마가 발언하는 말투, 성격이 다른 악령이 5개나 6개나 채워져 있는 것 같은 모습, 옮겨질 때마다 다른 사람이 된 것처럼 보이는 것도 포함되었다고 픽넷은 설명했다 [29] .픽넷 은 가톨릭 교도들 사이의 실천적인 사람들 사이에서 "빙의는 악마의 주름"설은 점차 설득력을 잃었지만, 영국 교회 는 지금도 악마 사냥을 전문으로 하는 목사단은 존재하고 있다고 했다 [29] .의학 영역이나 심리학의 영역에서 빙의를 이중 인격 혹은 다중 인격 의 표현으로 간주하는 생각은 많다 [29] . 「『자신』이라고 하는 것은 단일이 아니다. 복수의 자신의 모임으로 평상시는 그것이 일치해 움직이고 있다.혹은, 나날의 관리를 필두격의 그것에 맡기고 있다.」피크넷 은 이에 대해 , 이 설명의 예에서는, 영매 행위에 대해서는 맞지 않고, 영매행위의 경우, 「필두격」의 그것은, 분명히 뭔가 다른 실재와 같이 보이는 경우가 많고, 또 영매는 트랜스 상태가 되면, 그 사람이 정상적인 상황이라면 절대 알지 못하는 정보를 제공한다고 주장한다 [29] .

문학에 그려진 빙의 [ 편집 ]「액세스」- 메츠다 테츠야 의 소설

" 백호 마기 "- 사이토 요 의 소설

각주 [ 편집 ]

↑ a b 『광사원』 제4판, 제5판

^ a b c d e f g Yu Renli 의 "초정상 현상" Cheng Jia Shufang, 2001, 76페이지. ISBN 978-4880861159 .

^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x 이케가미 료쇼 "제5장" 년, 157-194 페이지. ISBN 4047033545 .

^ Daher, Jorge Cecílio Jr; Damiano, Rodolfo Furlan; Lucchetti, Alessandra Lamas Granero; Moreira-Almeida, Alexander; Lucchetti, Giancarlo (2017-01). "뇌 너머의 의식 가능성과 관련된 경험에 대한 연구: 글로벌 과학 산출물에 대한 서지학적 분석" (한글). 신경 및 정신 질환 저널 205 (1): 37. doi : 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000625 . ISSN 0022-3018 .

↑ 일본 TV「수수께끼의 빙의 현상을 쫓아!」( 웨이백 머신 )

^ Hecker, Tobias; Braitmayer, Lars; van Duijl, Marjolein (2015-12-01). "세계적 정신 건강과 트라우마 노출: 트라우마 경험과 영혼 소유 간의 관계에 대한 현재 증거" (영문). European Journal of Psychotraumatology 6 (1). doi : 10.3402/ejpt.v6.29126 . ISSN 2000-8066 . PMC PMC4654771 . PMID 26589259 .

↑ 『종교학 사전』555쪽, 도쿄대학 출판회 (1973/01) ISBN 9784130100274

↑ "종교학사전" pp. 249-250, 도쿄대학 출판부(1973/01) ISBN 9784130100274

^ a b p.159

↑ 아키하강 「조선 무속의 현지 연구」

↑ 『빙령신앙론』 전통과 현대사, 1982년

↑ 카와무라 쿠니히카 『빙의의 시좌』 아오미샤, 1997년

^ 167쪽

^ a b c 고동 철명 “현대 사상으로서의 그리스 철학” <코단샤 선서 메티에> 코단샤 1998년 ISBN 4062581272136-148쪽.

^ Jeffers, Ann (1996). 고대 팔레스타인과 시리아의 마법과 점술 . Brill. p. 181

↑ 야마자키 랜섬 카즈히코 『평화의 신의 승리』플레이즈 출판 p.47

↑ 『성서어구대사전』교문관

^ 올더스 헉슬리가 ' 루단의 악마' - The Devils of Loudun (1952)을 쓰고, 이것을 원작으로 켄 러셀 감독이 '육체의 악마'(1971)로서 영화화. 같은 사건은 야로스와프 이바슈키비치 '수녀 요안나'( 이와나미 문고 ) 등에도 그려져 있고, 예지 카발레로 비치가 동명의 영화화 (1961).

↑ 미셸 드 셀토 『루단의 빙의』 미스즈 서방 2008. 원서는 Michel de CERTEAU, LA POSSESSION DE L'OUDUN . PARIS, JULLIARD, 1970.

↑ 『종교학 사전』419페이지, 도쿄대학 출판회 (1973/01) ISBN 9784130100274

^ 시오 게츠 료코 “ 빙의를 긍정하는 사회 : 오키나와의 정신 의료사와 샤머니즘(빙의의 근대와 폴리틱스, 자유 테마 패널, <특집> 제64회 학술 대회 기요) 제4호, 일본 종교 학회, 2006년, 1035-1036페이지, doi : 10.20716/rsjars.79.4_1035 , ISSN 0387-3293 , NAID 110004752051 .

↑ 시오즈키 료코

↑ 정본 야나기타 쿠니오 모음 9권 247면

↑ 피리 「히시기」 세족학원 음악대학 전통음악 디지털 라이브러리

^ 회보 『사에즈리』 2012년 2호(2012년 10월 13일 발행) 축제 반자가 들리는 니가타현 리코더 교육 연구회

↑ 정본 야나기타 쿠니오 모음 10권 137면

↑ 고마쓰 카즈히코 『빙령 신앙론』 30페이지 전통과 현대사 1982년

^ 『마의 계보』 『다니가와 켄이치 저작집 1』 삼일 서방. 29쪽 서중에서 인용되는 이시즈카 존슌의 『일본의 빙물』에서는 이누가미 의 일종으로서 흡갈이 나온다.

^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o 린 피크넷 '초상현상 사전' 청토사, 1994년, 220-222쪽. ISBN 978-4791753079 .

참고 문헌 [ 편집 ]이케가미 료쇼 「죽은 자의 구제사 : 공양과 빙의의 종교학」카도카와 서점 <카도카와 선서>, 2003년. ISBN 4-04-703354-5 .

린 피크넷 저, 세키구치 아츠역 「 초상 현상의 사전」 청토사 , 1994년. ISBN 4-7917-5307-0 .

羽仁礼『超常現象大事典 : 영구 보존판』成甲書房、2001년、76頁. ISBN 4-88086-115-4 .

花渕馨也『정령의 아이 : 코모로 제도에 있어서의 빙의의 민족지』 춘풍사, 2005년. ISBN 4-86110-031-3 .

관련 항목 [ 편집 ]신탁 - 신 강하에 의한 하나님과 영혼의 계시와 예언무 / 무녀 - 후, Kannagi

위자보드 / 오토마티즘

생령 / 이타코아련 / 심신자

빙의근짐승 빙 / 관 여우 / 개신 / 오사키 - 일본에 분포하는 빙물의 전승

악마 빙빙 / 악마 지불 / 악령 얼룩 - 악마 빙빙의 대처 방법

해리성 정체성 장애

해리성 장애

해리(심리학)

최면 / 제안

모리타 마사마 - 모리타 요법 으로 유명. 기도성 정신병을 연구했다.

외부 링크 [ 편집 ]오카다 야스오 「빙어의 현상론 -그 구조 분석 - (상)」 「일본의사학 잡지」 제44권 제1호, 일본의사학회, 1998년 3월, 3-25페이지, ISSN 05493323 , NAID 10006591976 .

오카다 야스오 「빙어의 현상론 -그 구조 분석 - (아래)」 「일본의사학 잡지」 제44권 제3호, 일본의사학회, 1998년 9월, 369-384페이지, ISSN 05493323 , NAID 10006592109 .

사카이 타카히로 「 현재까지 의 빙고 연구와 그 문제점 2013년, 123-140페이지, ISSN 1341-7541 , NAID 120005430682 .

오미야 사신 「일본에 있어서의 빙의 연구의 일 측면-정신 의학의 시점으로부터-」 「기타쇼 대학 북방권 학술 정보 센터 연보」 제6호, 키타 쇼 대학 북방권 학술 정보 센터, 2014년, 1-6페이지, ISSN 2185-3096 , NAID 120005569010 .

이시이 미호 「접촉 영역에 있어서의 빙의, 접촉 영역으로서의 빙의 : 가나의 신령제사를 사례로서」 「콘택트 존」 제1호, 교토 대학 인문 과학 연구소 인문학 국제 연구 센터, 2007년 3월, 116- 129 페이지, NAID 120005307096 .

『薛公瓚傳(솔건창정)』과 한국의 빙의담 고 영령, 국제일본문화연구센터 『괴이·요괴문화의 전통과 창조──우치와 소토의 관점에서』, 2015.1.30

===

Toggle the table of contents

Spirit possession

26 languages

Article

Talk

Tools

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Not to be confused with Obsession (Spiritism) or Mediumship.

Part of a series on the

Paranormal

show

Main articles

show

Skepticism

show

Parapsychology

show

Related

v

t

e

Part of a series on

Anthropology of religion

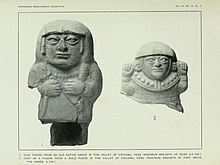

Two ancient anthropomorphic figures from Peru

show

Basic concepts

show

Case studies

show

Related articles

show

Major theorists

show

Journals

show

Religions

Social and cultural anthropology

v

t

e

Spirit possession is an unusual or an altered state of consciousness and associated behaviors which are purportedly caused by the control of a human body and its functions by spirits, ghosts, demons, angels, or gods.[1] The concept of spirit possession exists in many cultures and religions, including Buddhism, Christianity,[2][unreliable source?] Haitian Vodou, Dominican 21 Divisions, Hinduism, Islam, Wicca, and Southeast Asian, African, and Native American traditions. Depending on the cultural context in which it is found, possession may be considered voluntary or involuntary and may be considered to have beneficial or detrimental effects on the host.[3] The experience of spirit possession sometimes serves as evidence in support of belief in the existence of spirits, deities or demons.[4] In a 1969 study funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, spirit-possession beliefs were found to exist in 74% of a sample of 488 societies in all parts of the world, with the highest numbers of believing societies in Pacific cultures and the lowest incidence among Native Americans of both North and South America.[1][5] As Pentecostal and Charismatic Christian churches move into both African and Oceanic areas, a merger of belief can take place, with demons becoming representative of the "old" indigenous religions, which Christian ministers attempt to exorcise.[6]

Organized religions[edit]

Christianity[edit]

See also: Baptism with the Holy Spirit and Holy laughter

Further information: Exorcism in Christianity

From the beginning of Christianity, adherents have held that possession derives from the Devil (i.e. Satan) and demons. In the battle between Satan and Heaven, Satan is believed to engage in "spiritual attacks", including demonic possession, against human beings by the use of supernatural powers to harm them physically or psychologically.[1] Prayer for deliverance, blessings upon the man or woman's house or body, sacraments, and exorcisms are generally used to drive the demon out.

Some theologians, such as Ángel Manuel Rodríguez, say that mediums, like the ones mentioned in Leviticus 20:27, were possessed by demons. Another possible case of demonic possession in the Old Testament includes the false prophets that King Ahab relied upon before re-capturing Ramoth-Gilead in 1 Kings 22. They were described as being empowered by a deceiving spirit.[7]

The New Testament mentions several episodes in which Jesus drove out demons from persons.[8] Whilst most Christians believe that demonic possession is an involuntary affliction,[9] some biblical verses have been interpreted as indicating that possession can be voluntary. For example, Alfred Plummer writes that when Devil entered into Judas Iscariot in John 13:27, this was because Judas had continually agreed to Satan's suggestions to betray Jesus and had wholly submitted to him.[10]

The New Testament indicates that people can be possessed by demons, but that the demons respond and submit to Jesus Christ's authority:

In the synagogue, there was a man possessed by a demon, an evil spirit. He cried out at the top of his voice, "Ha! What do you want with us, Jesus of Nazareth? Have you come to destroy us? I know who you are—the Holy One of God!" "Be quiet!" Jesus said sternly. "Come out of him!" Then the demon threw the man down before them all and came out without injuring him. All the people were amazed and said to each other, "What is this teaching? With authority and power he gives orders to evil spirits and they come out!" And the news about him spread throughout the surrounding area

— Luke 4:33–35[11]

It also indicates that demons can possess animals as in the exorcism of the Gerasene demoniac.

Catholicism[edit]

Main article: Exorcism in the Catholic Church

Roman Catholic doctrine states that angels are non-corporeal, spiritual beings[12] with intelligence and will.[13] Fallen angels, or demons, are able to "demonically possess" individuals without the victim's knowledge or consent, leaving them morally blameless.[14]

The Catholic Encyclopedia says that there is only one apparent case of demonic possession in the Old Testament, of King Saul being tormented by an "evil spirit" (1 Samuel 16:14), but this depends on interpreting the Hebrew word "rûah" as implying a personal influence which it may not, so even this example is described as "not very certain". In addition, Saul was only described to be tormented, rather than possessed, and he was relieved from these torments by having David play the lyre to him.[15]

Exorcism of the Gerasene Demonaic

Exorcism of the Gerasene DemonaicCatholic exorcists differentiate between "ordinary" Satanic/demonic activity or influence (mundane everyday temptations) and "extraordinary" Satanic/demonic activity, which can take six different forms, ranging from complete control by Satan or demons to voluntary submission:[14]Possession, in which Satan or demons take full possession of a person's body without their consent. This possession usually comes as a result of a person's actions; actions that lead to an increased susceptibility to Satan's influence.

Obsession, which includes sudden attacks of irrationally obsessive thoughts, usually culminating in suicidal ideation, and which typically influences dreams.

Oppression, in which there is no loss of consciousness or involuntary action, such as in the biblical Book of Job in which Job was tormented by Satan through a series of misfortunes in business, material possessions, family, and health.

External physical pain caused by Satan or demons.

Infestation, which affects houses, objects/things, or animals; and

Subjection, in which a person voluntarily submits to Satan or demons.

In the Roman Ritual, true demonic or Satanic possession has been characterized since the Middle Ages, by the following four typical characteristics:[16][17]Manifestation of superhuman strength.

Speaking in tongues or languages that the victim cannot know.

Revelation of knowledge, distant or hidden, that the victim cannot know.

Blasphemous rage, obscene hand gestures, using profanity and an aversion to holy symbols, names, relics or places.

The New Catholic Encyclopedia states, "Ecclesiastical authorities are reluctant to admit diabolical possession in most cases, because many can be explained by physical or mental illness alone. Therefore, medical and psychological examinations are necessary before the performance of major exorcism. The standard that must be met is that of moral certitude (De exorcismis, 16). For an exorcist to be morally certain, or beyond reasonable doubt, that he is dealing with a genuine case of demonic possession, there must be no other reasonable explanation for the phenomena in question".[18]

Official Catholic doctrine affirms that demonic possession can occur as distinguished from mental illness,[19] but stresses that cases of mental illness should not be misdiagnosed as demonic influence. Catholic exorcisms can occur only under the authority of a bishop and in accordance with strict rules; a simple exorcism also occurs during baptism.[1]

Anglican[edit]

The infliction of demonic torment upon an individual has been chronicled in premodern Protestant literature. In 1597, King James discussed four methods of daemonic influence upon an individual in his book Daemonologie:[20]Spectra, being the haunting and troubling of certain houses or solitary places.

Obsession, the following and outwardly torment of an individual at diverse hours to either weaken or cast diseases upon the body, as in the Book of Job.

Possession, the entrance inwardly into an individual to beget uncontrollable fits, induce blasphemies,

Faerie, being the influence those who voluntarily submit to consort, prophesy, or servitude.

King James attested that the symptoms derived from demonic possession could be discernible from natural diseases. He rejected the symptoms and signs prescribed by the Catholic church as vain (e.g. rage begotten from Holy Water, fear of the Cross, etc.) and found the exorcism rites to be troublesome and ineffective to recite. The Rites of the Catholic Church to remedy the torment of demonic spirits were rejected as counterfeit since few possessed could be cured by them. In James' view: "It is easy then to understand that the casting out of Devils, is by virtue of fasting and prayer, and in-calling of the name of God, suppose many imperfections be in the person that is the instrument, as CHRIST himself teaches us (Mat. 7) of the power that false Prophets all have cast out devils".[21]

In medieval Great Britain, the Christian church had offered suggestions on safeguarding one's home. Suggestions ranged from dousing a household with holy water, placing wax and herbs on thresholds to "ward off witches occult", and avoiding certain areas of townships known to be frequented by witches and Devil worshippers after dark.[22] Afflicted persons were restricted from entering the church, but might share the shelter of the porch with lepers and persons of offensive life. After the prayers, if quiet, they might come in to receive the bishop's blessing and listen to the sermon. They were fed daily and prayed over by the exorcists and, in case of recovery, after a fast of from 20 to 40 days, were admitted to the Eucharist, and their names and cures entered in the church records.[23] In 1603, the Church of England forbade its clergy from performing exorcisms because of numerous fraudulent cases of demonic possession.[19]

Baptist[edit]

In May 2021, the Baptist Deliverance Study Group of the Baptist Union of Great Britain, a Christian denomination, issued a "warning against occult spirituality following the rise in people trying to communicate with the dead". The commission reported that "becoming involved in activities such as Spiritualism can open up a doorway to great spiritual oppression which requires a Christian rite to set that person free".[24]

In September 2023, Pastor Rick Morrow of Beulah Church in Richland, Missouri gave a sermon in which he presented the cause of autism as, "the devil's attacked them, he's brought this infirmity upon them, he's got them where he wants them". He asserted that the cure for the neurodevelopmental disorder was prayer by claiming to "know a minister who has seen lots of kids that are autistic, that he cast that demon out, and they were healed, and then he had to pray and their brain was rewired and they were fixed."[25] Members of the pastor's community found his comment to be "derogatory toward individuals with certain disabilities." Their public outcry led to Morrow's resignation from the school board on which he was a member.[26]

Evangelical[edit]

In both charismatic and evangelical Christianity, exorcisms of demons are often carried out by individuals or groups belong to the deliverance ministries movement.[27] According to these groups, symptoms of such possessions can include chronic fatigue syndrome, homosexuality, addiction to pornography, and alcoholism.[28] The New Testament's description of people who had evil spirits includes a knowledge of future events (Acts 16:16) and great strength (Act 19:13–16),[8] among others, and shows that those with evil spirits can speak of Christ (Mark 3:7–11).[8] Some Evangelical denominations believe that demonic possession is not possible if one has already professed their faith in Christ, because the Holy Spirit already occupies the body and a demon cannot enter.

Islam[edit]

Various types of creatures, such as jinn, shayatin, ʻafarit, found within Islamic culture, are often held to be responsible for spirit possession. Spirit possession appears in both Islamic theology and wider cultural tradition.

Although opposed by some Muslim scholars, sleeping near a graveyard or a tomb is believed to enable contact with the ghosts of the dead, who visit the sleeper in dreams and provide hidden knowledge.[29] Possession by ʻafarit (a vengeful ghost) are said to grant the possessed some supernatural powers, but it drives them insane as well.[30]

Jinn are much more physical than spirits.[31] Due to their subtle bodies, which are composed of fire and air (marijin min nar), they are purported to be able to possess the bodies of humans. Such physical intrusion of the jinn is conceptually different from the whisperings of the devils.[32]: 67 Since jinn are not necessarily evil, they are distinguished from cultural concepts of possession by devils/demons.[33]

Since such jinn are said to have free will, they can have their own reasons to possess humans and are not necessarily harmful. There are various reasons given as to why a jinn might seek to possess an individual, such as falling in love with them, taking revenge for hurting them or their relatives, or other undefined reasons.[34][35] At an intended possession, the covenant with the jinn must be renewed.[36] Soothsayers (kāhin pl. kuhhān), would use such possession to gain hidden knowledge. Inspirations from jinn by poets requires neither possession nor obedience to the jinn. Their relationship is rather described as mutual.[37]

The concept of jinn-possession is alien to the Quran and derives from pagan notions.[38] It is widespread among Muslims and also accepted by most Islamic scholars.[39] It is part of the aqida (theological doctrines) in the tradition of Ashari,[32] and the Atharis, such as ibn Taimiyya and ibn Qayyim.[32]: 56 Among Maturidites it is debated, as some accept it, but it has been challenged since the early years by Maturidite scholars such as al-Rustughfanī.[40] The Mu'tazila are associated with substituting jinn-possession by devilish-whisperings, denying bodily possession altogether.[41]

In contrast to jinn, the devils (shayatin) are inherently evil.[42] Iblis, the father of the devils, dwells in the fires of hell, although not suffering wherein, he and his children try to draw people into damnation of hell.[43] Devils don't physically possess people, they only tempt humans into sin by following their lower nafs.[44][45] Hadiths suggest that the devils whisper from within the human body, within or next to the heart, and so "devilish whisperings" (Arabic: waswās وَسْوَاس) are sometimes thought of as a kind of possession.[46] Unlike possession by jinn, the whispering of devils affects the soul instead of the body.

Demons (also known as div), though part of the human conception, get stronger through acts of sin.[47] By acts of obedience (to God), they get weaker. Although a human might find pleasure in obeying the demons first, according to Islamic thought, the human soul can only be free if the demons are bound by the spirit (ruh).[48] Sufi literature, as in the writings of Rumi and Attar of Nishapur, pay a lot of attention to how to bind the inner demons. Attar of Nishapur writes: "If you bind the div, you will set out for the royal pavilion with Solomon" and "You have no command over your self's kingdom [body and mind], for in your case the div is in the place of Solomon".[49] He further links the demons to the story alluded in the Quran (38:34) that a demon replaced the prophet Solomon: one must behave like a triumphant 'Solomon' and chain the demons of the nafs or lower self, locking the demon-prince into a 'rock', before the rūḥ (soul) can make the first steps to the Divine.[50]

Judaism[edit]

Main articles: Shedim, Shade (mythology), and Dybbuk

Although forbidden in the Hebrew Bible, magic was widely practiced in the late Second Temple Period and well documented in the period following the destruction of the Temple into the 3rd, 4th, and 5th centuries C.E.[51][52] Jewish magical papyri were inscriptions on amulets, ostraca and incantation bowls used in Jewish magical practices against shedim and other unclean spirits. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, Jewish methods of exorcism were described in the Book of Tobias.[53][54]

In the 16th century, Isaac Luria, a Jewish mystic, wrote about the transmigration of souls seeking perfection. His disciples took his idea a step further, creating the idea of a dybbuk, a soul inhabiting a victim until it had accomplished its task or atoned for its sin.[55] The dybbuk appears in Jewish folklore and literature, as well as in chronicles of Jewish life.[56] In Jewish folklore, a dybbuk is a disembodied spirit that wanders restlessly until it inhabits the body of a living person. The Baal Shem could expel a harmful dybbuk through exorcism.[57]

African traditions[edit]

Central Africa[edit]

Democratic Republic of the Congo[edit]

Zebola[58] is a women's spirit possession dance ritual practised by certain ethnic groups of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It is believed to have therapeutic qualities and has been noted in the West as a traditional form of psychotherapy.

It originated among the Mongo people but is also practised among various ethnic groups in Kinshasa.[59]

Horn of Africa[edit]

Ethiopia[edit]

Among the Gurage people of Ethiopia, spirit possession is a common belief. William A. Shack postulated that it is caused by Gurage cultural attitudes about food and hunger, while they have a plentiful food supply, cultural pressures that force the Gurage to either share it to meet social obligations, or hoard it and eat it secretly cause feelings of anxiety. Distinctions are drawn between spirits that strictly possess men, spirits that possess women, and spirits that possess victims of either sex. A ritual illness that only affects men is believed to be caused by a spirit called awre. This affliction presents itself by loss of appetite, nausea, and attacks from severe stomach pains. If it persists, the victim may enter a trance-like stupor, in which he sometimes regains consciousness long enough to take food and water. Breathing is often labored. Seizures and trembling overcome the patient, and in extreme cases, partial paralysis of the extremities.[60]

If the victim does not recover naturally, a traditional healer, or sagwara, is summoned. Once the sagwara has determined the spirit's name through the use of divination, he prescribes a routine formula to exorcise the spirit. This is not a permanent cure, it merely allows the victim to form a relationship with the spirit while subject to chronic repossession, which is treated by repeating the formula. This formula involves the preparation and consumption of a dish of ensete, butter, and red pepper. During this ritual, the victim's head is covered with a drape, and he eats the ensete ravenously while other ritual participants participate by chanting. The ritual ends when the possessing spirit announces that it is satisfied. Shack notes that the victims are overwhelmingly poor men, and that women are not as food-deprived as men, due to ritual activities that involve food redistribution and consumption. Shack postulates that the awre serves to bring the possessed man to the center of social attention, and to relieve his anxieties over his inability to gain prestige from redistributing food, which is the primary way in which Gurage men gain status in their society.[60]

The belief in spirit possession is part of the native culture of the Sidama people of southwest Ethiopia. Anthropologists Irene and John Hamer postulated that it is a form of compensation for being deprived within Sidama society, although they do not draw from I.M. Lewis (see Cultural anthropology section under Scientific views). The majority of the possessed are women whose spirits demand luxury goods to alleviate their condition, but men can be possessed as well. Possessed individuals of both sexes can become healers due to their condition. Hamer and Hamer suggest that this is a form of compensation among deprived men in the deeply competitive society of the Sidama, for if a man cannot gain prestige as an orator, warrior, or farmer, he may still gain prestige as a spirit healer. Women are sometimes accused of faking possession, but men never are.[61]

East Africa[edit]

Kenya

See also: SakaThe Digo people of Kenya refer to the spirits that supposedly possess them as shaitani. These shaitani typically demand luxury items to make the patient well again. Despite the fact that men sometimes accuse women of faking the possessions in order to get luxury items, attention, and sympathy, they do generally regard spirit possession as a genuine condition and view victims of it as being ill through no fault of their own. Other men suspect women of actively colluding with spirits in order to be possessed.[62]

The Giriama people of coastal Kenya believe in spirit possession.[63]

MayoteIn Mayotte, approximately 25% of the adult population, and five times as many women as men, enter trance states in which they are supposedly possessed by certain identifiable spirits who maintain stable and coherent identities from one possession to the next.[64]

MozambiqueIn Mozambique, a new belief in spirit possession appeared after the Mozambican Civil War. These spirits, called gamba, are said to be identified as dead soldiers, and allegedly overwhelmingly possess women. Prior to the war, spirit possession was limited to certain families and was less common.[65]

UgandaIn Uganda, a woman named Alice Auma was reportedly possessed by the spirit of a male Italian soldier named Lakwena ('messenger'). She ultimately led a failed insurrection against governmental forces.[66]

TanzaniaThe Sukuma people of Tanzania believe in spirit possession.[67]

A now-extinct spirit possession cult existed among the Hadimu women of Zanzibar, revering a spirit called kitimiri. This cult was described in an 1869 account by a French missionary. The cult faded by the 1920s and was virtually unknown by the 1960s.[68]

Southern Africa[edit]

See also: AmafufunyanaA belief in spirit possession appears among the Xesibe, a Xhosa-speaking people from Transkei, South Africa. The majority of the supposedly possessed are married women. The condition of spirit possession among them is called intwaso. Those who develop the condition of intwaso are regarded as having a special calling to divine the future. They are first treated with sympathy, and then with respect as they allegedly develop their abilities to foretell the future.[69]

West Africa[edit]One religion among Hausa people of West Africa is that of Hausa animism, in which belief in spirit possession is prevalent.

African diasporic traditions[edit]

In many of the African diaspora religions possessing spirits are not necessarily harmful or evil, but are rather seeking to rebuke misconduct in the living.[70] Possession by a spirit in the African diaspora and traditional African religions can result in healing for the person possessed and information gained from possession as the spirit provides knowledge to the one they possessed.[71][72][73]

Haitian Vodou[edit]

In Haitian Vodou and related African diaspora religions, one way that those who participate or practice can have a spiritual experience is by being possessed by the Loa (or lwa). When the Loa descends upon a practitioner, the practitioner's body is being used by the spirit, according to the tradition. Some spirits are believed to be able to give prophecies of upcoming events or situations pertaining to the possessed one, also called a Chwal or the "Horse of the Spirit". Practitioners describe this as a beautiful but very tiring experience. Most people who are possessed by the spirit describe the onset as a feeling of blackness or energy flowing through their body.[74]

Umbanda[edit]

The concept of spirit possession is also found in Umbanda, an Afro-Brazilian folk religion. According to tradition, one such possessing spirit is Pomba Gira, who possesses both women and males.[75]

Hoodoo[edit]

The culture of Hoodoo was created by African-Americans. There are regional styles to this tradition, and as African-Americans traveled, the tradition of Hoodoo changed according to African-Americans' environment. Hoodoo includes reverence to ancestral spirits, African-American quilt making, herbal healing, Bakongo and Igbo burial practices, Holy Ghost shouting, praise houses, snake reverence, African-American churches, spirit possession, some Nkisi practices, Black Spiritual churches, Black theology, the ring shout, the Kongo cosmogram, Simbi water spirits, graveyard conjuring, the crossroads spirit, making conjure canes, incorporating animal parts, pouring of libations, Bible conjuring, and conjuring in the African-American tradition. In Hoodoo, people become possessed by the Holy Ghost. Spirit possession in Hoodoo was influenced by West African Vodun spirit possession. As Africans were enslaved in the United States, the Holy Spirit (Holy Ghost) replaced the African gods during possession.[76] "Spirit possession was reinterpreted in Christian terms."[71][77] In African-American churches this is called being filled with the Holy Ghost. "Walter Pitts (1993) has demonstrated the modern importance of 'possession' within African- American Baptist ritual, tracing the origins of the ecstatic state (often referred to as 'getting the spirit') to African possessions."[78] Church members in Black Spiritual churches become possessed by spirits of deceased family members, the Holy Spirit, Christian saints, and other biblical figures from the Old and New Testament of the Bible. It is believed when people become possessed by these spirits they gain knowledge and wisdom and act as intercessors between people and God.[79] William Edward Burghardt Du Bois (W. E. B. Du Bois) studied African-American churches in the early twentieth century. Du Bois asserts that the early years of the Black church during slavery on plantations was influenced by Voodooism.[80][81]

The Kongo cosmogram inspired the ring shout, a sacred dance in Hoodoo performed to become possessed by the Holy Spirit or ancestral spirits.

The Kongo cosmogram inspired the ring shout, a sacred dance in Hoodoo performed to become possessed by the Holy Spirit or ancestral spirits.Through counterclockwise circle dancing, ring shouters built up spiritual energy that resulted in the communication with ancestral spirits, and led to spirit possession. Enslaved African Americans performed the counterclockwise circle dance until someone was pulled into the center of the ring by the spiritual vortex at the center. The spiritual vortex at the center of the ring shout was a sacred spiritual realm. The center of the ring shout is where the ancestors and the Holy Spirit reside at the center.[82][83][84] The Ring Shout (a sacred dance in Hoodoo) in Black churches results in spirit possession. The Ring Shout is a counterclockwise circle dance with singing and clapping that results in possession by the Holy Spirit. It is believed when people become possessed by the Holy Spirit their hearts become filled with the Holy Ghost which purifies their heart and soul from evil and replace it with joy.[85] The Ring Shout in Hoodoo was influenced by the Kongo cosmogram a sacred symbol of the Bantu-Kongo people in Central Africa. It symbolizes the cyclical nature of life of birth, life, death, and rebirth (reincarnation of the soul). The Kongo cosmogram also symbolizes the rising and setting of the sun, the sun rising in the east and setting in the west that is counterclockwise, which is why ring shouters dance in a circle counterclockwise to invoke the spirit.[86][87]

Asian traditions[edit]

Yahwism[edit]

There are indications that trance-related practices might have played a role in the prophetic experiences of adherents of Yahwism. According to Martti Nissinen, Yahwist prophets may have received messages from the different gods and goddesses in the Yahwist Pantheon through a state of trance possession. This theory can be reconstructed from Sumerian Mythology, a similar theology to that of Yahwism, where the standard prophetic designations in the Akkadian language, muḫḫûm/muḫḫūtum (masc./fem., Old Babylonian) and maḫḫû/maḫḫūtu (masc./fem., Neo-Assyrian), are derived from the Akkadian verb maḫû "to become crazy, to go into a frenzy."[88] According to bible scholar Simon B. Parker, trance rituals may have occurred such as nudity or a less extreme alternative, a trance where the person to enter trance receives the god or spirit into their body.[89]

Further according to Nissinen, the Hebrew Bible, may contain evidence that trance-related practices may have been the origins of the Jewish traditions of prophetic messages.[88]

Nissinen also recorded that music was an essential part to these trance-ceremonies in the Ancient Near-East and so it can be reconstructed it could have been found in Yahwism.[88] Instruments such as the tambourine, harps, lyres, and flutes may have been utilized, as those were common instruments in Ancient Israel.[90] Along with music, incense may have also been used, either as an offering, or to be used as an entheogen, or possibly as both.

Exorcisms were also common. They can be reconstructed from both Medieval Jewish texts and texts from neighboring ancient cultures that practiced exorcisms. Exorcists acting almost like shamans would do rituals to exorcise one of a "demon" or evil spirit. According to Gina Konstantopoulos, a figure named an "Āshipu" acted as an exorcist in Mesopotamia and were trained in many fields of occultism, priesthood and herbalism.[91] As amulets (called teraphim) were also used in Yahwism to ward off evil spirits, it may also be reconstructed that there were people in Ancient Israel who acted as exorcists or shamans who would do specific rituals to ward off evil spirits. As mentioned previously, these may have included music, incense, prayers, and trance-rituals. According to Reimund Leicht, formulae was used ward off the evil, along with ritualistic sacrifices.[92]

Buddhism[edit]

According to the Indian medical literature and Tantric Buddhist scriptures, most of the "seizers", or those that threaten the lives of young children, appear in animal form: cow, lion, fox, monkey, horse, dog, pig, cat, crow, pheasant, owl, and snake. Apart from these "nightmare shapes", the impersonation or incarnation of animals can in some circumstances also be highly beneficial, according to Michel Strickmann.[93]

Ch'i Chung-fu, a Chinese gynecologist writing early in the 13th century, wrote that in addition to five sorts of falling frenzy classified according to their causative factors, there were also four types of other frenzies distinguished by the sounds and movements given off by the victim during his seizure: cow, horse, pig, and dog frenzies.[93]

Buddha, resisting the demons of Mara

Buddha, resisting the demons of MaraIn Buddhism, a māra, sometimes translated as "demon", can either be a being suffering in the hell realm[94] or a delusion.[95] Before Siddhartha became Gautama Buddha, He was challenged by Mara, the embodiment of temptation, and overcame it.[96] In traditional Buddhism, four forms of māra are enumerated:[97]Kleśa-māra, or māra as the embodiment of all unskillful emotions, such as greed, hate, and delusion.

Mṛtyu-māra, or māra as death.

Skandha-māra, or māra as metaphor for the entirety of conditioned existence.

Devaputra-māra, the deva of the sensuous realm, who tried to prevent Gautama Buddha from attaining liberation from the cycle of rebirth on the night of the Buddha's enlightenment.[98]

It is believed that a māra will depart to a different realm once it is appeased.[94]

East Asia[edit]

See also: East Asian religions

Certain sects of Taoism, Korean shamanism, Shinto, some Japanese new religious movements, and other East Asian religions feature the idea of spirit possession. Some sects feature shamans who supposedly become possessed; mediums who allegedly channel beings' supernatural power; or enchanters are said to imbue or foster spirits within objects, like samurai swords.[99] The Hong Kong film Super Normal II (大迷信, 1993) shows the true famous story of a young lady in Taiwan who possesses the dead body of a married woman to live her pre-determined remaining life.[100] She is still serving in the Zhen Tian Temple in Yunlin County.[101]

China[edit]

Main article: Chinese spirit possession

Background[edit]

China is a country where 73.56% of the population is defined as Chinese folk religion/unaffiliated (nonreligion). Therefore, the Chinese population's knowledge of spirit possession is not majorly obtained from religion. Instead, the concept is spread through fairy tales/folk tales and literary works of its traditional culture. In essence, the concept of soul possession has penetrated into all aspects of Chinese life, from people's superstitions, folk taboos, and funeral rituals, to various ghost-themed literary works, and has continued to spread to people's lives today.

Development[edit]

Spirit possession in China was prominent until the Communist takeover in the 1950s and most of the data gathered on this topic will be from the late 18th century. Some Chinese believe that illnesses to man is due to the possession of an evil yin spirit (kuei). These evil spirits become such when the deceased are not worshiped by the family, they have died unexpectedly, or did not follow Confucius's ideals of filial piety and ancestral reverence accordingly. These evil spirits cause unexplainable disasters, agricultural shocks and possessions. Disease is the cause of the supernatural where they do not have control over. Usually in the writings about this, the healers are the ones being described with detail, not so much the patient. Magical practices are sometimes what spirit possession is referred to as. It is very hard to distinguish between the religion, magic and local traditions. This is because many times, all three are fused together, so sometimes trying to distinguish between them is hard.

Shaman[edit]

Another type of spirit possession works through a shaman, a prophet, healer and religious figure with the power to partially control spirits and communicate for them. Messages, remedies and even oracles are delivered through the shaman. This is sometimes used by people who would like to become important figures. Usually, shamans give guidance that reflects the customer's existing values.[102]

Yin-yang theory[edit]

The yin-yang theory is one of the most important bases and components of Chinese traditional culture. The yin-yang theory has penetrated into various traditional Chinese cultural things including calendar, astronomy, meteorology, Chinese medicine, martial arts, calligraphy, architecture, religion, feng shui, divination, etc. The yin-yang theory also applies to spirit possession. In general, one is considered to be "weak", when the yin and yang in the body are imbalanced, especially when the yin is on the dominant side. The spirits, which are categorized as the yin side, will then take control of these individuals with the imbalanced and yin-dominant situation more easily.Shi (Chinese ancestor veneration)

Shamanism of the Solon People (Inner Mongolia)

Tangki

Japan[edit]Misaki

India[edit]

Ayurveda[edit]

Bhūtavidyā, the exorcism of possessing spirits, is traditionally one of the eight limbs of Ayurveda.

Rajasthan[edit]

The concept of spirit possession exists in the culture of modern Rajasthan. Some of the spirits allegedly possessing Rajasthanis are seen as good and beneficial, while others are seen as malevolent. The good spirits are said to include murdered royalty, the underworld god Bhaironji, and Muslim saints and fakirs. Bad spirits are believed to include perpetual debtors who die in debt, stillborn infants, deceased widows, and foreign tourists. The supposedly possessed individual is referred to as a ghorala, or "mount". Possession, even if by a benign spirit, is regarded as undesirable, as it is seen to entail loss of self-control, and violent emotional outbursts.[103]

Tamil Nadu[edit]

See also: Buta Kola

Tamil women in India are said to experience possession by peye spirits. According to tradition, these spirits overwhelmingly possess new brides, are usually identified as the ghosts of young men who died while romantically or sexually frustrated, and are ritually exorcised.[104]

Sri Lanka[edit]

The Coast Veddas, a social group within the minority group of Sri Lankan Tamil people in Eastern Province, Sri Lanka, enter trances during religious festivals in which they are regarded as being possessed by a spirit. Although they speak a dialect of Tamil, during trances they will sometimes use a mixed language that contains words from the Vedda language.[105]

Southeast Asia[edit]

Indonesia[edit]

In Bali, the animist traditions of the island include a practice called sanghyang, induction of voluntary possession trance states for specific purposes. Roughly similar to voluntary possession in Vaudon (Voodoo), sanghyang is considered a sacred state in which hyangs (deities) or helpful spirits temporarily inhabit the bodies of participants. The purpose of sanghyang is believed to be to cleanse people and places of evil influences and restore spiritual balance. Thus, it is often referred to as an exorcism ceremony.[citation needed] In Sulawesi, the women of the Bonerate people of Sulawesi practice a possession-trance ritual in which they smother glowing embers with their bare feet at the climax. The fact that they are not burned in the process is considered proof of the authenticity of the possession.[106]

Influenced by the religion of Islam, among the several spirits in Indonesian belief are demons (setan), composed of fire, prone to anger and passion. They envy humans for their physical body, and try to gain control of it. When they assault a human, they would intrude their mind, trying to displace the human spirit. The human's mind would adapt to the passions of anger, violence, irrationality and greed, the intruding demon is composed of. The demon is believed to alter the person, giving him supernatural attributes, like strength of many men, ability to appear in more than one place, or assume the form of an animal, such as a tiger or a pig, or to kill without touching. Others become lunatics, resembling epilepsy. In extreme cases, the presence of the demon may alter the condition of the body, matching its own spiritual qualities, turning into a raksasha.[107]

Malaysia[edit]

Female workers in Malaysian factories have allegedly become possessed by spirits, and factory owners generally regard it as mass hysteria and an intrusion of irrational and archaic beliefs into a modern setting.[108] Anthropologist Aihwa Ong noted that spirit possession beliefs in Malaysia were typically held by older, married women, whereas the female factory workers are typically young and unmarried. She connects this to the rapid industrialization and modernization of Malaysia. Ong argued that spirit possession is a traditional way of rebelling against authority without punishment, and suggests that it is a means of protesting the untenable working conditions and sexual harassment that the women were compelled to endure.[108]

The Americas and Caribbean[edit]

Indo-Caribbean Shaktism[edit]

In Indo-Caribbean Madrasi Religion, a state of trance-possession known as "Sami Aduthal" in Tamil and as a "manifestation" in English occurs whence a devotee enters a trance state after praying. It is an essential part to Indo-Caribbean Shakti ceremonies, being accompanied by Tappu drumming, the singing of devotional songs, and the drumming of Udukai drums.

Ceremonies called Pujas often include the drumming of three to five tappu to invoke the deity to the space.[109] Then, the head pujari receives the God or Goddess into their body, acting as a medium. A mixture of water, turmeric powder, and neem leaves are poured onto the medium, as it is believed that the God's energy heats up the body while the water and turmeric with the neem leaves cools it down again.[110] Puja services are often held once a week.

Oceanic traditions[edit]

Melanesia[edit]

The Urapmin people of the New Guinea Highlands practice a form of group possession known as the "spirit disco" (Tok Pisin: spirit disko).[111] Men and women gather in church buildings, dancing in circles and jumping up and down while women sing Christian songs; this is called "pulling the [Holy] spirit" (Tok Pisin: pulim spirit, Urap: Sinik dagamin).[111][112] The songs' melodies are borrowed from traditional women's songs sung at drum dances (Urap: wat dalamin), and the lyrics are typically in Telefol or other Mountain Ok languages.[112] If successful, some dancers will "get the spirit" (Tok Pisin: kisim spirit), flailing wildly and careening about the dance floor.[111] After an hour or more, those possessed will collapse, the singing will end, and the spirit disco will end with a prayer and, if there is time, a Bible reading and sermon.[111] The body is believed to normally be "heavy" (ilum) with sin, and possession is the process of the Holy Spirit throwing the sins from one's body, making the person "light" (fong) again.[111] This is a completely new ritual for the Urapmin, who have no indigenous tradition of spirit-possession.[111]

Micronesia[edit]

The concept of spirit possession appears in Chuuk State, one of the four states of Federated States of Micronesia. Although Chuuk is an overwhelmingly Christian society, traditional beliefs in spirit possession by the dead still exist, usually held by women, and "events" are usually brought on by family conflicts. The supposed spirits, speaking through the women, typically admonish family members to treat each other better.[113]

European traditions[edit]

Ancient Greece[edit]

Further information: Nympholepsy

Italian folk magic[edit]

In traditional Italian folk magic spirit possessions are not uncommon. It is known in this culture that a person may be possessed by multiple entities at once. The way to be rid of the spirit(s) would be to call for a curatore, guaritore or pratico which all translate to healer or knowledgeable one from Italian. These healers would perform sacred rituals to be rid of the spirits; the rituals are passed down through generations and vary based on the region in Italy. It is said that for many Italian rituals specifically those to be rid of negative spirits, that the information may only be shared on Christmas Eve (specifically for il malocchio). If the family is religious they may even call in a priest to perform a traditional catholic exorcism on the spirit(s).[114]

Shamanic traditions[edit]

Further information: Shamanism § Beliefs

Shamanism is a religious practice that involves a practitioner who is believed to interact with a spirit world through altered states of consciousness, such as trance.[115][116] The goal of this is usually to direct these spirits or spiritual energies into the physical world, for healing or another purpose.[115]

New religious movements[edit]

Wicca[edit]

Wiccans believe in voluntary possession by the Goddess, connected with the sacred ceremony of Drawing Down the Moon. The high priestess solicits the Goddess to possess her and speak through her.[117]

Scientific views[edit]

Cultural anthropology[edit]

The works of Jean Rouch, Germaine Dieterlen, and Marcel Griaule have been extensively cited in research studies on possession in Western Africa that extended to Brazil and North America due to the slave trade.[118][119]

The anthropologist I.M. Lewis noted that women are more likely to be involved in spirit possession cults than men are, and postulated that such cults act as a means of compensation for their exclusion from other spheres within their respective cultures.[120]

Physical anthropology[edit]

Anthropologists Alice B. Kehoe and Dody H. Giletti argued that the reason that women are more commonly seen in Afro-Eurasian spirit possession cults is because of deficiencies in thiamine, tryptophan-niacin, calcium, and vitamin D. They argued that a combination of poverty and diet cause this problem, and that it is exacerbated by the strains of pregnancy and lactation. They postulated that the involuntary symptoms of these deficiencies affecting their nervous systems have been institutionalized as spirit possession.[121]

Medicine and psychology[edit]

See also: Culture-bound syndrome and Bicameral mentality

Spirit possession of any kind, including demonic, is just one psychiatric or medical diagnosis recognized by the DSM-5 or the ICD-10: "F44.3 Trance and possession disorders".[122] In clinical psychiatry, trance and possession disorders are defined as "states involving a temporary loss of the sense of personal identity and full awareness of the surroundings" and generally classed as a type of dissociative disorder.[123]

People alleged to be possessed by spirits sometimes exhibit symptoms similar to those associated with mental illnesses such as psychosis, catatonia, mania, Tourette's syndrome, epilepsy, schizophrenia, or dissociative identity disorder,[124][125][126] including involuntary, uncensored behavior, and an extra-human, extra-social aspect to the individual's actions.[127] It is not uncommon to ascribe the experience of sleep paralysis to demonic possession, although it's not a physical or mental illness.[128] Studies have found that alleged demonic possessions can be related to trauma.[129]

In entry article on dissociative identity disorder, the DSM-5 states, "possession-form identities in dissociative identity disorder typically manifest as behaviors that appear as if a 'spirit,' supernatural being, or outside person has taken control such that the individual begins speaking or acting in a distinctly different manner".[130] The symptoms vary across cultures.[123] The DSM-5 indicates that personality states of dissociative identity disorder may be interpreted as possession in some cultures, and instances of spirit possession are often related to traumatic experiences—suggesting that possession experiences may be caused by mental distress.[129] In cases of dissociative identity disorder in which the alter personality is questioned as to its identity, 29 percent are reported to identify themselves as demons.[131] A 19th century term for a mental disorder in which the patient believes that they are possessed by demons or evil spirits is demonomania or cacodemonomanis.[132]

Some have expressed concern that belief in demonic possession can limit access to health care for the mentally ill.[133]

Notable examples[edit]

Purported demonic possessions[edit]

In chronological order:

Martha Brossier (1578)

Aix-en-Provence possessions (1611)

Mademoiselle Elizabeth de Ranfaing (1621)

Loudun possessions (1634)

Dorothy Talbye trial (1639)

Louviers possessions (1647)

The Possession of Elizabeth Knapp (1671)

George Lukins (1788)

Gottliebin Dittus (1842)

Antoine Gay (1871)

Johann Blumhardt (1842)

Clara Germana Cele (1906)

Exorcism of Roland Doe (1940)

Anneliese Michel (1968)

Michael Taylor (1974)

Arne Cheyenne Johnson (1981)

Tanacu exorcism (2005)

See also[edit]

Religion portal

Religion portalAutomatic writing

Body hopping

Demonology

Divine madness

Enthusiasm

Jamaican Maroon spirit-possession language

List of exorcists

Necromancy

Sexuality in Christian demonology

Spirit spouse

Spiritualist Church

The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner

Unclean spirit

Walk-in

References[edit]

^ Jump up to:a b c d Jones (2005), p. 8687.

^ Mark 5:9, Luke 8:30