조지 린드벡

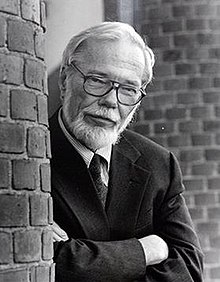

조지 A. 린드벡(George Arthur Lindbeck, 1923년 3월 10일 ~ 2018년 1월 8일[1])는 미국의 루터교 신학자이며 예일 대학교의 교수였다. 그는 에큐메니칼 신학자였으며 한스 프라이와 함께 후기 자유주의신학의 창립자중에 한 사람이었다.[2]

초기 생활 및 교육[편집]

린드벡은 1923년 중국 뤄양 시에서 미국 선교사의 아들로 태어났다. 그는 중국과 한국에서 16세까지 양육을 받았으며,[3] 몸이 좋지 않아서 세상과 자주 고립되었다.[4] 그는 1939년 구스타브스 아돌피우스 대학교에 입학하여 1943년에 학사(B.A.)를 마쳤다. 1946년 예일 대학교에서 B.D.를 마쳤다. 학부를 졸업후에 에티엔 질송과 함께 중세연구소에서 그리고 폴 비그나우스와 함께 파리에서 고등연구실습원에서 2년 있었다. 캐나다와 프랑스에서 공부를 이어오다 예일대학교로 돌아와 박사 과정을 마쳤다.1955년 그의 박사논문은 중세연구에 강조를 둔 것으로 프란치스코회 신학자 둔스 스코투스였다.[3]

활동[편집]

린드벡은 중세연구에 관심이 많았고 로마 카톨릭 교회와 에큐메니칼 운동에 참여하였다. 제2차 바티칸 공의회 에는 옵서버로 참가하였다. 루터란과 카톨릭 사이에 에큐메니칼 대화에도 중요한 역할을 하였다. 1968년부터 1987년까지에는 이 두 그룹의 중재역할도 하였다. 바티칸 회의 참가한 것들을 1994년 출판하였다. 1952년 예일 대학교 신학부 교수로 임용되어서 1993년 은퇴하였다. 그의 책은 <후기자유주의 시대의 교회>(The Church in a Postliberal Age)가 2002년 출판되었다. 2018년 1월 8일에 96세를 일기로 사망하였다.

문화-언어의 종교이론[편집]

그에게 가장 잘 알려진 작품은 1984년에 출판된 <교리의 본질>(Nature of Doctrine: Religion and Theology in a Postliberal Age)이다. 이 책은 큰 영향을 주었고, 후기 자유주의신학의 형성에 결정적인 역할을 하였다. 이 책에서 린드벡은 공통된 개인의 경험으로 종교적 진리를 규정하는 근대 자유주의 개신교의 사유를 거부하고, 신앙공동체의 신조와 실천을 종교 이해의 기초로 삼는 문화- 언어적 접근방식을 제시했다. 합리적 논증이나 정서적 경험보다 믿음과 세계관 형성에 강조를 두었다. 전통적인 기독교 신학의 인식-명제적 접근과 자유주의의 경험-표현주의적 접근이 포스트모던적 종교 현상에 대한 해결책이 되지 못함을 인식한 조지 린드벡은 기존의 두 접근법들을 극복할 대안으로서 문화-언어적 접근법을 제시한다.

첫 번째 주장은 종교를 절대적 규범이 아니라 문화나 언어로 이해한다는 것인데, 이는 인간이 언어를 배우듯 종교에도 문화-언어적으로 친해진다는 것이다.

두 번째 주장은 교리를 진리로 보지 않고 문법으로 이해하자는 것이다. 모두가 종교와 교리를 문법적으로 이해한다면 종교 간의 다툼과 충돌의 문제는 사라진다고 한다. 여러 종교가 마치 언어에 좋고 나쁨이나 옳고 그름이 없는 것처럼 나름대로의 체계 안에서 해석될 수 있기 때문이다.[5]

평가[편집]

린드벡의 접근법이 종교 상호간에 화해를 가능케 하고, 실행성을 강조하고, 또 성경을 귄위 있는 신학적 텍스트로 삼았다는 점은 중요한 기여로 꼽을 수 있다. 하지만 이것은 텍스트 자체보다는 교회의 해석에 더 큰 비중을 두었고, 진리를 내적 일관성으로 격하시켰고, 모든 종교를 동일한 가치로 보는 극단적 상대주의와 언어가 종교생활에 필수적이라는 엘리트주의를 조장했을 뿐 아니라 신학적 종말론을 주장함으로써 명제주의로 회귀했다는 문제점을 안고 있다. 린드벡의 문화-언어의 종교이론을 신학적 보수주의와 자유주의의 한계를 극복할 대안으로는 부족하다는 평가가 있다.[6]

같이 보기[편집]

각주[편집]

- ↑ Sterling, Greg (2018년 1월 19일). “George Lindbeck, 1923-2018”. 《divinity.yale.edu》 (영어). 2018년 1월 20일에 확인함.

- ↑ Francisco, Grant D. Miller (1999). “George Lindbeck, (1923-)”. 《Boston Collaborative Encyclopedia of Western Theology》. 2018년 1월 20일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 Eckerstorfer, Bernhard A. (Fall 2004). “The one church in the postmodern world: reflections on the life and thought of George Lindbeck”. 《Pro Ecclesia》: 399–423. ISSN 1063-8512.

- ↑ Lindbeck, George A. (Interviewee) (2006년 11월 28일). “Performing the faith: an interview with George Lindbeck”. 《Christian Century》: 28–35. ISSN 0009-5281.

- ↑ 저해종, "조지 린드벡의 문화-언어의 종교이론 비평", 한국콘텐츠학회논문지 제14권 제4호, 2014.4, 456-466

- ↑ 저해종, "조지 린드벡의 문화-언어의 종교이론 비평", 한국콘텐츠학회논문지 제14권 제4호, 2014.4, 456-466

참고 문헌[편집]

- Adiprasetya, Joas. “George A. Lindbeck and Postliberal Theology”. 2008년 7월 30일에 확인함.

- “262 Chosen for Guggenheim Awards”. 《New York Times》. 1988년 4월 10일. 2008년 7월 30일에 확인함.

- “The Hartford Declaration”. 《Theology Today》 32 (1): 94–97. April 1975. 서문에 헤이즐 앤드류스

George Lindbeck

George Lindbeck | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | George Arthur Lindbeck March 10, 1923 Luoyang, China |

| Died | January 8, 2018 (aged 94) Florida, United States |

| Nationality | American |

| Spouse | Violette Lindbeck[1] |

| Academic background | |

| Alma mater | |

| Thesis | Is Duns Scotus an Essentialist? (1955) |

| Doctoral advisor | Robert Lowry Calhoun |

| Other advisors | |

| Influences | |

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | Theology |

| School or tradition | |

| Institutions | Yale University |

| Doctoral students | |

| Notable students | |

| Notable works | The Nature of Doctrine (1984) |

| Influenced | |

George Arthur Lindbeck (March 10, 1923 – January 8, 2018) was an American Lutheran theologian. He was best known as an ecumenicist and as one of the fathers of postliberal theology.[13][14]

Early life and education[edit]

Lindbeck was born on March 10, 1923, in Luoyang, China, the son of American Lutheran missionaries. Raised in that country and in Korea for the first seventeen years of his life,[15] he was often sickly as a child and found himself often isolated from the world around himself.[16]

He attended Gustavus Adolphus College, graduating with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1943. He went on to do graduate work at Yale University, receiving his Bachelor of Divinity degree in 1946. After his undergraduate work he spent a year at the Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies with Étienne Gilson in Toronto then two years at the École Pratique des Hautes Études with Paul Vignaux in Paris. He earned his Doctor of Philosophy degree from Yale in 1955 concentrating on medieval studies, delivering a dissertation on the Franciscan theologian Duns Scotus.[15]

Career[edit]

Lindbeck first gained attention as a medievalist and as a participant in ecumenical discussions in academia and the church. He was a "delegate observer" to the Second Vatican Council. After that time, he made important contributions to ecumenical dialogue, especially between Lutherans and Roman Catholics.[16] From 1968 to 1987 he was a member of the Joint Commission between the Vatican and Lutheran World Federation.[15] In 1994, Lindbeck spoke at length about his memories of Vatican II with George Weigel, and a transcript of his interview with Weigel was published in the December 1994 edition of First Things.

His best-known work is The Nature of Doctrine: Religion and Theology in a Postliberal Age, published in 1984. It was widely influential and is one of the key works in the formation and founding of postliberal theology.

He was appointed to the Yale Divinity School faculty in 1952 before his studies were finished, and remained there until his retirement in 1993. His book The Church in a Postliberal Age was published in 2002.

He was a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and a recipient of the Wilbur Cross Medal from the Yale Graduate School Alumni Association.[17]

Lindbeck died on January 8, 2018.[1]

Selected works[edit]

- Lindbeck, George A. (1984). The Nature of Doctrine: Religion and Theology in a Postliberal Age. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664246181

- Lindbeck, George A. (2003). The Church in a Postliberal Age. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802839954

References[edit]

- ^ a b Sterling, Greg (19 January 2018). "George Lindbeck, 1923–2018". Yale Divinity School. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- ^ Lindbeck, George (1989). "Response to Bruce Marshall". The Thomist. 53 (3): 405. doi:10.1353/tho.1989.0018. S2CID 171415066. Cited in Adiprasetya, Joas (2005). "George A. Lindbeck and Postliberal Theology". Boston Collaborative Encyclopedia of Modern Western Theology. Boston: Boston University. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Placher, William C. (1996). The Domestication of Transcendence: How Modern Thinking About God Went Wrong. Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press. p. xi. ISBN 978-0-664-25635-7.

- ^ a b Adiprasetya, Joas (2005). "George A. Lindbeck and Postliberal Theology". Boston Collaborative Encyclopedia of Modern Western Theology. Boston: Boston University. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Johansson, Lars (1999). "Mystical Knowledge, New Age, and Missiology". In Kirk, J. Andrew; Vanhoozer, Kevin J. (eds.). To Stake a Claim: Mission and the Western Crisis of Knowledge. New York: Orbis Books. p. 178. ISBN 978-1-57075-274-2.

- ^ a b Knowles, Steven (2010). Beyond Evangelicalism: The Theological Methodology of Stanley J. Grenz. Farnham, England: Ashgate. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-7546-6608-0.

- ^ "Kathryn Tanner | Yale Divinity School".

- ^ "Centre for Catholic Studies".

- ^ Erwin, R. Guy (23 January 2018). "Memories of Lindbeck: Prayerful Ecumenist". The Living Church. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Ditmer, Bob (24 January 2018). "Postliberal Theologian George Lindbeck Dies at 94". ChurchLeaders.com. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ a b Placher, William C. (2007). The Triune God: An Essay in Postliberal Theology. Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press. p. ix. ISBN 978-0-664-23060-9.

- ^ Sumner, George (18 January 2018). "Missionary to Postmodernity". The Living Church. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Francisco, Grant D. Miller (1999). "George Lindbeck, (1923–)". Boston Collaborative Encyclopedia of Western Theology. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- ^ Shellnutt, Kate. "Died: George Lindbeck, Father of Postliberal Theology". News & Reporting. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- ^ a b c Eckerstorfer, Bernhard A. (2004). "The One Church in the Postmodern World: Reflections on the Life and Thought of George Lindbeck". Pro Ecclesia. 13 (4): 399–423. doi:10.1177/106385120401300403. ISSN 1063-8512. S2CID 211947839.

- ^ a b Lindbeck, George A. (Interviewee) (28 November 2006). "Performing the Faith: An Interview with George Lindbeck". Christian Century: 28–35. ISSN 0009-5281.

- ^ "George A. Lindbeck, 1946 B.D., 1955 Ph.D. | Yale Divinity School". divinity.yale.edu. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

Further reading[edit]

- "262 Chosen for Guggenheim Awards". The New York Times. 10 April 1988. Retrieved 30 July 2008.

- "The Hartford Declaration". Theology Today. 32 (1): 94–97. April 1975. doi:10.1177/004057367503200114. S2CID 220982493. preface by Hazel Andrews

The Nature of Doctrine, 25th Anniversary Edition: Religion and Theology in a Postliberal Age

See all 3 images

See all 3 imagesFollow the Author

George A. Lindbeck

Follow

The Nature of Doctrine: Religion and Theology in a Postliberal Age Paperback – 1 January 1984

by lindbeck (Author)

4.6 out of 5 stars 30 ratings

See all formats and editions

Kindle

$23.04Read with Our Free App

Paperback

$33.00

1 Used from $29.686 New from $33.00

This groundbreaking work lays the foundation for a theology based on a cultural-linguistic approach to religion and a regulative or rule theory of doctrine. Although shaped intimately by theological concerns, this approach is consonant with the most advanced anthropological, sociological, and philosophical thought of our times.

Publisher : Westminster John Knox Press (1 January 1984)

Language : English

Paperback : 144 pages

ISBN-10 : 0664246184

ISBN-13 : 978-0664246181

Dimensions : 15.24 x 0.79 x 22.86 cmBest Sellers Rank: 639,442 in Books (See Top 100 in Books)152 in Comparative Religion Textbooks

1,054 in Christian Systematic Theology

1,739 in Christianity TextbooksCustomer Reviews:

4.6 out of 5 stars 30 ratings

Follow

George A. Lindbeck

4.6 out of 5 stars

4.6 out of 5

30 global ratings

5 star 80%

4 star 8%

3 star 6%

2 star 6%

1 star 0% (0%)

0%

How are ratings calculated?

Review this product

Share your thoughts with other customers

Write a customer review

Sponsored

Top reviews

Top review from Australia

Young bae Son

5.0 out of 5 stars GoodReviewed in Australia on 13 November 2015

Verified Purchase

Ono of best basic book for theology...

HelpfulReport abuse

See all reviews

Top reviews from other countries

Translate all reviews to English

Jim Harries

5.0 out of 5 stars Cultural-Linguistic models to guide the churchReviewed in the United Kingdom on 23 August 2016

Verified Purchase

Serving the church in Zambia (1988-1991) I found myself on a steep learning curve. I had to unlearn much that I had previously thought I understood about Africa while I was still in the UK. I resisted doing so then. I have continued to resist doing so since then, having lived in Kenya from 1993. Something deep in my Western upbringing tells me that African people CANNOT BE as different from ‘us Westerners’ as they appear to be.

My battle to discover and to confirm same-ness has not yet ended. One reason it has yet to end, is because of never-ending ways in which it is presupposed. It seems that almost everything that the West does in Africa (well, the parts of Africa with which I am familiar) tries to assume that African people are no different from them. Just as constantly, the above is found to be not-true, resulting in lies, concealment of truth, corruption, ongoing poverty, outside dependency. An individual missionary has to deal with this concealing of truth. They can be forced into denial of what is being observed, latent depression as things do not work as they should, or to being at loggerheads with accepted Western wisdom.

George A. Lindbeck dares go where few tread. His short book The Nature of Doctrine has received wide attention, and been widely criticised. Critics have had three reservations in particular, Marshall tells us: 1. Lindbeck fails to sufficiently support Christian belief, or reason itself. 2. Lindbeck proposes a withdrawal of the church into a ghetto. 3. Lindbeck’s bowing to postmodern relativism has him deny the objectivity of truth.

Lindbeck’s primary concern is ecumenical unity. In pursuit of that unity, he endeavours to unearth the otherwise intangible reasons moderns struggle to accommodate difference. Traditionally, Christian doctrines are considered cognitively to be propositional truths, Lindbeck tells us. That is, Christians, especially theologians, make propositions about truth on the basis that those truths are already established in the spiritual realm. Hence Catholics declare that the bread of the Holy Communion turns into the body of Christ. Protestants deny this. It would seem on this basis that a prerequisite to ecumenical unity is capitulation by one side. How come, then, that some unity is being achieved, for example between Catholics and Lutherans, Lindbeck asks (127)?

An alternative basis for unity arises from contemporary understanding of doctrines as founded in experiential-expressiveness. This founds unity within the common heart of humanity. Because God is actually one, so the argument goes, religions’ efforts at reaching him are merely an inadequate grasping of one truth. Doctrines are symbols that help people to express their deep yearnings. According to these theorists, apparent differences between doctrines among Christian denominations, and even between ‘religions’ like Islam and Hinduism could be resolved if one were only to realise this. This dominant contemporary understanding is “logically and empirically vacuous” Lindbeck tells us (18). No wonder some inter-religious and ecumenical discussions go around in circles.

The cognitive approach that founds itself in propositions, and theories based on experiential-expressiveness, dominate theology. Other disciplines in today’s world run on a third, the cultural-linguistic, approach. For Lindbeck, the failure to take this latter seriously is what is bringing the church into a ghetto. Interaction, as a result, between theologically related disciplines and the university are minimal; the two are seen as mutually inimical. But, explains Lindbeck, taking the cultural-linguistic approach seriously could explain what is happening and enable ecumenical progress in today’s world. That is to say, variations in doctrine are responses to contexts in which the church finds itself. When the context changes, then clearly different responses are required in order to communicate the same truths. One-size declaration does not fit all, shall we say.

Two things at least have me agree with Lindbeck. One is a foundational question; why did anthropology and theology part ways? Anthropology (coming from the biblical Greek term anthropos) has roots in Christian theology. In recent centuries, anthropology has been adversarial to theology. Many in the contemporary world might see anthropology, and secularism in general to be ‘winning’, and the church to be ‘losing’. Rejection by the church of contemporary linguistics and anthropology, Lindbeck states (this is in my own words) has been a rejection of reason, for which the church is suffering.

I see the above in sharper focus as a Christian theologian engaging indigenous African Christianity. That brings me ecumenical challenges somewhat like those faced by Lindbeck. When western theologians behave like juggernauts determined to ignore African particularisms, I acquire empathy with Lindbeck! The above juggernauts choose to ignore language and to ignore culture, thinking that our common humanity gives us sufficient basis for clear communication, which in practice is always the West communicating their pearls of wisdom using Western languages, requiring Africans to ‘adjust’ this wisdom to their context. (It is rather telling that the reverse does not happen.) At the same time that this goes on, a clearly recognised divide continues, centuries on, between White and Black churches even within the USA, right in the heart of the West itself. This vision of cultural superiority enabling open communication is primarily forced by Western hegemony achieved on the back of superior economy.

“Locating … the constant … in a religion … [in] inner experience … result[s] in the identification of the normative form of the religion with either the truth claims or the experiences appropriate to a particular world … [e.g.] Florida” states Lindbeck (70). In so doing, he identifies the abiding ‘sin’ of Western theologians reaching Africa: they end up communicating not the God of the Scriptures, but their home culture. To not-do-so requires use of appropriate categories, hence as pre-requisite, a grasp of indigenous culture, plus use of languages that make sense of that culture. To do this, frankly, as a further pre-requisite, requires a theologian to avoid forcing their agenda using outside funding.

I do consider Lindbeck to be misguided to consider non-Christian traditions to be ‘religions’. His own articulation is clearly and deeply rooted in Christian texts, history and tradition, so why assume it transfers to Islam or Hinduism? Lindbeck’s world, deeply rooted in discussions in Vatican II, now more than 50 years in the past, is rather different from my world in contemporary Africa. Yet the truths he identifies as means for understanding of doctrines that may rescue faith in Jesus from scholarly isolationism and Western imperialism have profound relevance to inter-cultural communication in contemporary times. What Lindbeck is talking about, is the need for contextualised theology.

Read less

3 people found this helpfulReport abuse

5.0 out of 5 stars The Nature of DoctrineReviewed in Brazil on 21 March 2017

Verified Purchase

Reflexão relevante. O assunto é pertinente e atual. Recomendo também a leitura de "A Gênese da Doutrina" de Alister McGrath.

One person found this helpfulReport abuse

Translate review to English

Michael

4.0 out of 5 stars Cognitive Propositional!Reviewed in the United States on 4 December 2011

Verified Purchase

Lindbeck categorizes doctrine as one of the following three:

Cognitive Propositional. This is the understanding that doctrines make truth claims about objective reality. Propositionalism finds certitude in Scripture and emphasizes the cognitive aspect of faith and religion. This has been the traditional approach of Orthodox Christian belief. Synthesizing these Scriptural truths and doctrines is also a part of this method. Thinkers in this group remain critical of post-foundational approaches.

Experiential Expressive. This method, which emphasizes religious feeling, was thought to have found universal objectivity for religious truth. While it was presupposed that all religious feeling had a common core experience, it was discovered that there was no clear evidence that this was the case. Further difficulty with this approach was found in specifying distinctive features of religious feeling, such that “the assertion of commonality becomes logically and empirically vacuous” (18).

Cultural Linguistic. This is Lindbeck's method. It's design is ecumenically minded but has fostered a larger discussion pertaining to its use in theological method. At the risk of sounding too reductionistic it might be said that this alternative seeks to understand religion as a culture or a semiotic language. Religion shapes the entirety of life, not just cognitive or emotional dimensions. A religion is a “comprehensive scheme or story used to structure all dimensions of existence” (21). And “its vocabulary of symbols and its syntax may be used for many purposes, only one of which is the formulation of statements about reality. Thus while a religion's truth claims are often of the utmost importance to it (as in the case of Christianity), it is, nevertheless, the conceptual vocabulary and the syntax or inner logic which determine the kinds of truth claims the religion can make” (21).

In terms of measuring religions for truth, categorical truth is what is to be accepted, which may or may not correspond to reality (37). Truth, in this regard, is what is meaningful (34). Lindbeck uses a map metaphor in which the knowledge provided by the map is only “constitutive of a true proposition when it guides the traveler rightly” (38). This dynamic understanding of truth is not answerable to static propositional truth claims. Religioin must be utilized correctly to provide ontology, or meaning (38).

The possibility of salvation as solus Christus is said to conform to this approach. “One must, in other words, learn the language of faith before one can know enough about its message knowingly to reject it and thus be lost” (45). Lindbeck has in mind here fides ex audit and envisions a post-mortem offer of salvation.

In readdressing propositional truth, it is said that religious sentences have first-order or ontological truth or falsity only in determinate settings (54; recall the map metaphor). Understood in this way, the Cultural Linguistic approach proves to successfully supply categorical, symbolic, and propositional truths.

Rule Theory maintains that what is “abiding and doctrinally significant” about religion is not found in inner experience or their propositional truth, but “in the story it tells and in the grammar that informs the way the story is told and used” (66). In order to make sense of religious experiences they must be interpreted within an entire comprehensive framework.

Lindbeck presents a softer view of doctrine, which is less truth-claiming, and more about community rules. Doctrines, thus, may be reversible or irreversible, unconditional or conditional, temporary or permanent.

Read less

10 people found this helpfulReport abuse

Ben Kickert

5.0 out of 5 stars Postliberal approach to religion and theologyReviewed in the United States on 10 December 2008

Verified Purchase

Ben Kickert. Review of George A Lindbeck, The Nature of Doctrine: Religion Theology in a Postliberal Age (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 1984).

In 1984 George A. Lindbeck presented a new approach to viewing religion and doctrine in his book The Nature of Doctrine. As the subtitled indicates, it was his desire to provide a "framework for discussion" (10) that was compatible with the emerging postliberal movement. What he came up with is non-theological approach that advocates a cultural-linguistic view of religion and a rules-based understanding of doctrine. He then evaluates his proposal in light of various test cases. This review will assess the usefulness of this approach and evaluate the book as a whole.

The author makes his personal religious convictions clear. He is a Christian, with a great interest in unity in the midst of diversity (7-8). He wants to be able to adequately address not only divergent beliefs, but the dynamic nature of beliefs (9). In order to do this, he calls for a paradigm shift on behalf of theologians and students of religion (8). Lindbeck admits the approach he lays out is mostly theoretical, but invites others to evaluate it (11). The book is laid out in 6 chapters. The first serves as an introduction while chapters 2-3 address the cultural-linguistic approach. Chapters 4-5 deal with rules theory of doctrine while chapter 6 outlines a larger theological framework.

In his introductory chapter, Lindbeck critiques the approaches to religion that were dominant in his day. He describes two major methods: the cognitive and the experiential-expressive. The former focuses on truth claims as the primary determinate of religion while the later uses experiences. The author also looks at a third approach that seeks to synthesize these two. In light of his goal, the author rejects these and turns instead to an understanding that views religion in terms similar to culture or language. He expands this discussion in chapter 2 and argues for the superiority of a cultural-linguistic approach. The non-theological framework he presents contends that like culture "religions produce experience" (33) rather than being the explainer of experience. Furthermore, like language, it must be learned and interiorized; only then can a person full participate through expression and experience (35-37). This is a complete reversal of the experiential-expressive model. Chapter 4 evaluates whether this non-theological theory of religion can be religiously useful by looking at the concept of superiority of religions, their interrelationship, salvation for non-adherents and the overarching concepts of religious truth. The author concludes a superior religion is categorically true, rightly utilized, and corresponds to ultimate reality (52). From here religions can regard themselves as different without judging superiority. In regards to the salvation question, Lindbeck take a universalist approach.

Chapter 4 moves to the issue of doctrine within religions. It is here the author lays out his approach. He contends, "a rule theory not only is doctrinally possible but has advantages over other positions" (73). The result is a view of doctrine that operates like grammatical rules rather than absolute faith statements. This allows for differences within religions and between religions to stand without the need to reconcile them. This theory is tested in chapter 5 by evaluating three contentious issues: Christology, Mariology and Infallibility. He concludes what matters is not conclusions, but rather what lies behind them; this provides reconcilement for the first two issues, but not the later. For the author, a rules based approach to doctrine is best utilized in relation to behavioral requirements.

The final chapter of this book serves to place cultural-linguistic theory and a rules-based approach to doctrine within the larger framework by evaluating their implications. These views push for an intra-systemic (or intra-textual) approach to meaning wherein the religion gives meaning rather than describes meaning. Within this system, religious text are formative within the communities that adapt them. Religions and sacred texts hold the power to shape communities. This, the author concludes, is a necessary part of the wider society and culture. Lindbeck is essentially arguing for a relativistic view of religions while advocating religious communities resist relativism so they can teach the culture and language of religion. His ultimate conclusion is that the theories he has presented in his book are valuable, but in the end each religion must be true to its roots and message.

In evaluating Lindbeck's proposal, the first issue that must be considered is his approach. He is clear in pointing out that his theory is non-theological. As such, his primary purpose is not to provide a tool for Christians to evaluate their belief systems. Instead, it is his desire to offer a theory of religion that allows an observer to judge and understand a system of beliefs entirely on their own merit. Therefore, before any judgment can be made on conclusions, this method should be evaluated. Since the author is clearly writing from a Christian perspective, one could expect a theory that supports the claims of orthodox Christianity. This book does not set, nor achieve this goal. Lindbeck is much more concerned about unity than about orthodoxy. However, from a non-theistic approach to understanding religion, the approach the author employs is exceedingly useful and relevant.

The primary advantage of Lindbeck's approach to religion lies in its ability to study and evaluate religions intra-systemically without having to evaluate ontological correctness. In effect, each religion can stand alone and be evaluated on it own merits. This is extremely helpful when viewing faith systems objectively, especially from an anthropological viewpoint. In addition to providing a non-judgmental way to evaluate religions, the cultural-linguistic articulated in this book provides fresh insight and perspective on the role religion plays in communal formation and spiritual development. It is certainly important to ask questions about how experiences can be explained through religion, but just as important is an understanding of how religions shapes and informs those experiences. This framework allows individuals to better appreciate the contributions and unique features of a religion. Additionally, the rules based approach to doctrine allows for the dynamicity apparent in most religions. Rather than seek to reconcile transitions, Lindbeck's approach embraces these.

The Nature of Doctrine is not without its limits and shortcomings. In emphasizing ecumenical and interfaith unity, the book has lost some of its value for evaluating and informing traditional, orthodox theologies. For instance, the universalism he argues for is outside the scope of orthodoxy for many evangelical traditions. It could be argued that Lindbeck misses the goal of being religiously useful. This is perhaps most apparent in the concluding chapter; here the author admits his framework explains the assimilation process, but does little to convince those who "share in the intellectual high cultural" (124). In effect, he is concluding cultural-linguistic theory and rules theory of doctrine can explain religions, but may not bolster them. A final shortcoming of the books is one readily admitted to by the author. At the time of it's writing the approach presented was largely untested and thus relied heavily on theory. It is almost as if Lindbeck was throwing out an idea for others to try. Considering the brevity of the book, it seems a more thorough treatment would have possible and useful.

The contributions of Lindbeck cannot be overlooked and should be applauded. The ideas outlined in the pages of this book continue to reverberate 24 years later. The lens the author provides his readers is innovative and practical; however, its practicality is primarily found in external evaluations of religion. One could assume that Lindbeck expected his theories to have been accepted or rejected by this point in history. However, the tension still remains between modern (especially evangelical) thinkers and postmoderns (or postliberals as Lindbeck calls them). Where ever a person falls on that continuum, they would be well served to join the discussion spurred by this book. We may not agree, but hopefully we can better understand each other.

Read less

15 people found this helpfulReport abuse

Rev. Ron Hooker (Yale Graduate)

5.0 out of 5 stars The Nature of DoctrineReviewed in the United States on 2 May 2014

Verified Purchase

Professor Lindbeck's timeless work is experiencing a bit of a revival. It is a great book for

well-educated Clergy and Lay Scholars. I was fortunate to have had him as a Professor. He was one of most outstanding at Yale. I shall always be thankful that for three decades,

I was able to read and re-read this great book! Rev. Ron Hooker (Yale Graduate)

Not often is such a great Reformation Scholar, Professor, and Faithful Christian, to be

found in one person. He is one of the last Vatican II Official Observers still living.

2 people found this helpfulReport abuse

See all reviews