SPIRITUALITY TODAY

Spring 1990, Vol.42 No. 1, pp.

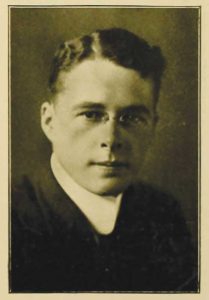

Jerry R. Flora:

Searching for an Adequate Life:

The Devotional Theology of Thomas R. Kelly| The mystical teaching of Quaker theologian Thomas Kelly continues to enrich and inspire a new generation of readers searching for a meaningful life in a world veering towards chaos. |

Jerry R. Flora earned the doctorate in theology from Southern Baptist Theological Seminary and since 1972 has been Professor of New Testament Theology at Ashland (Ohio) Theological Seminary. Prior to that he was a parish minister in Ohio, Indiana, and Washington, D.C.

|

ON the morning of January 17, 1941, a college professor in eastern Pennsylvania exclaimed to his wife, "Today will be the greatest day of my life."(1) He had just written to the religion editor at Harper and Brothers, accepting an invitation to speak with him in New York about a small book ,on devotional practice. The firm of Harper was definitely interested in the kind of fresh material this writer could produce. That evening, while drying the dinner dishes, he slumped to the floor with a massive coronary arrest and died almost instantly.

The writer was Thomas Raymond Kelly, professor of philosophy at Haverford College in suburban Philadelphia, considered to be the elite among Quaker colleges of America. Kelly had taught there for nearly five years, succeeding D. Elton Trueblood when the latter became chaplain at Stanford University. Forty seven years old at the time of his unexpected death, Kelly was a seminary graduate and a philosopher of unusually broad preparation. He was also coming to be known as a devotional writer of considerable freshness and power.

Three months after Kelly's death, Douglas Steere, his colleague in the philosophy department, submitted to Harper and Brothers five of his friend's devotional essays prefaced by a biographical memoir. That slender volume, A Testament of Devotion, has remained in print since 1941 and has been acclaimed by thoughtful readers of varying theological persuasions.

Thomas Kelly belonged to a succession of American Quakers who were philosophers by profession. Rufus M. Jones (1863-1948) mentored Kelly throughout the years of his pilgrimage and outlived his protege. Elton Trueblood (b. 1900) edited one of the Friends' magazines which introduced Kelly's writings to the public. Twenty-five years later Trueblood commented, "The sense of excitement, when Thomas Kelly:s essays began to come to the editorial desk, is still vivid." (2) Douglas Steere (b. 1901), Rhodes scholar and faculty colleague, compiled the volume which became known as A Testament of Devotion. The purpose of this article is to recount the outlines of Kelly's life, describe the contents of his devotional theology, and offer a summary analysis of it.

A QUAKER YOUTH

Thomas Raymond Kelly was born in 1893, a child of the Quaker faith as it was found at that time in south-central Ohio. This rnidwestern variety of the Society of Friends had come under the influence of the evangelical revivals that characterized the nineteenth century in the American middle West. Even now, Friends in Ohio are often nearly indistinguishable from other low-church or free-church Protestants. Kelly, born into that environment, lost his father at the age of four, after which his mother moved the family to Wilmington, Ohio. Her intention was that by living there her children could have the advantage of higher education at Wilmington College, a small Quaker school in that town.

Young Kelly grew up with both a perfectionistic streak and a sense of the joy of living. He was remembered for his impishness, his practical jokes, his daredevil motorcycle riding, later his skills as carpenter and sheet-metal worker, and finally his warm, open laughter. One friend wrote of him, "He laughed with the rich hearty abandon of wind and sun upon the open prairie. I have never heard richer, heartier laughter than his" (TD 7)(3)At the same time his life was marked by what has been termed "a passionate and determined quest for adequacy" (TD 1) in both scholarship and Christian devotion.

SCHOLAR AND TEACHER

Always interested in science, Kelly graduated from Wilmington College in 1913 with a chemistry major. He went the next year to Haverford College for additional study, there falling under the spell of Rufus M. Jones, the distinguished professor of philosophy. With Jones came also exposure to the more mystical side of the Friends movement, preserved better on the eastern seaboard than in Ohio.

That change of focus was accompanied by a never-ending interest in the Far East, which led him to Hartford Theological Seminary to prepare for missionary service.

World War I erupted in Europe, and, in true Quaker fashion, Kelly volunteered for civilian service overseas. He spent a year in England, working first with the YMCA, then with German prisoners of war because of his knowledge of their language.

Returning to the States, he finished seminary and married Lael Macy, daughter of a New England Congregational manse. Their twenty-one years of marriage were marked by frequent moves for him to study or teach, nagging financial problems which followed on this, and numerous physical ailments, some of which were undoubtedly stress-related.(4)

After their marriage he returned to Wilmington College, where he taught for two years (1919-21),

went back to Hartford, completing a doctorate in philosophy (1924), and was inducted into Phi Beta Kappa.

Dr. and Mrs. Kelly then spent a year in Berlin, working with the American Friends Service Committee in the reconstruction following Germany's war defeat.

Upon their return to the United States, Kelly was unable to find a position on the east coast and was forced to become a professor at Earlham College, a Quaker school in Richmond, Indiana. By this time he had come to dislike the Midwest, feeling that it did not have the intellectual stimulus of the East, and he went through a period of rebellion against the thinking and spirituality of his evangelical Ohio origins.

In 1930 Kelly returned to New England to begin a second doctorate in philosophy, this time at Harvard University. Through the early and mid-thirties he labored at that while teaching first at Wellesley College (1931-32) and then again at Earlham (1932-35).

This was the middle of the Great Depression, and Kelly's decision to return to Earlham was painful because it meant once more the Midwest that he had come to despise. Yet there were no other positions open to him until 1935 when he was able to move to the University of Hawaii to teach and to pursue advanced research in Eastern philosophies.

His long-awaited opportunity called in 1936, when Haverford College invited him to follow D. Elton Trueblood in a chair of philosophy. He brought to this new work not only his massive academic preparation, including the near-completed second doctorate at Harvard, but also his love for the eastern seaboard and all that it represented for him both intellectually and spiritually.

In 1937 his dissertation was published, receiving very favorable reviews. Like the thesis for his first doctorate, it studied the thought of a scientist who turned philosopher -- a pilgrimage quite similar to that of Kelly himself. But the Harvard Ph.D. was not yet his, needing only the oral defense of the now-published dissertation.

BREAKDOWN AND BREAKTHROUGH

So in the autumn of 1937 Thomas Kelly traveled north to Cambridge to sit for his orals, and there he lived out the nightmare of every Ph.D. candidate: he lost his memory. Since his mid-twenties, Kelly, always an intense individual, had experienced occasional "woozy spells." as he called them. This sometimes occurred under great stress, as in 1924 at the defense of his first dissertation. The committee at Hartford had patiently worked with him, his confidence and recall returned, and he gave a brilliant defense of his research. But the Harvard faculty was not sympathetic when Kelly went blank in 1937 trying to defend the dissertation he had written for them. They not only failed him on the defense, they also informed him that he would never be allowed a second chance.

In the days that followed, friends offered what help they could but nothing seemed to avail. His son continues the story:

"There is no exact record of what happened in the following weeks, but it is certain that sometime during the months of November or December, 1937, a change was wrought within the very foundation of his soul. He described it as being'shaken by the experience of Presence -- something that I did not seek, but that sought me ....' Stripped of his defenses and human self justification, he found, for the first time, a readiness to accept the outright gift of God's Love, and he responded with unlimited commitment to that leading.(5) His teaching colleague Douglas Steere, who spent uncounted hours walking Kelly through his grief, later wrote of his healing:

"He moved toward adequacy. A fissure in him seemed to close, cliffs caved in and filled up a chasm, and what was divided grew together within him. Science, scholarship, method remained good, but in a new setting" (TD 18). "...out of it seemed to come a whole new life orientation. What took place no one will ever know; but old walls caved in, the fierce academic ambition receded, and a new abandoned kind of fulfillment made its appearance."(6)

This life-changing experience showed through in two public lectures that Kelly prepared shortly afterward, lectures which he said wrote themselves. He then sailed for Germany in the summer of 1938, culminating three years of planning, in order to minister as he was able to the Friends in that country before Hitler closed it off from the rest of Europe. He came home, the last person off the ship, shaken by the suffering he had witnessed in Germany but buttressed by new experiences of divine love able to meet that agony. His friends recalled that for weeks afterward he said over and over, "I have been literally melted down by the love of God!" (TD 21).

Such first-hand acquaintance with reality, both human and divine, continued to be the trademark of his speaking and writing in the little more than two years which remained. Seventeen addresses and lectures appeared in the period following Kelly's failure until his sudden death in January, 1941. As people heard him speak and studied his writings, they detected a note of authenticity that was attractive and powerful. It was that note which led the religious books editor of Harper and Brothers to invite him to submit a manuscript for publication. Twenty-five years after A Testament of Devotion was posthumously published, his son Richard released Thomas Kelly: A Biography and The Eternal Promise, which contains the remainder of the essays and addresses.

JUDGMENT AND DOCTRINE

The worth of Thomas Kelly's legacy has been noted by such authors as D. Elton Trueblood (7) and Richard J. Foster. (8) Church historian E. Glenn Hinson of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary has, for many years, offered classes in devotional literature on his campus. In his opinion, "Thomas Kelly's A Testament of Devotion... is a contemporary classic... a wonderfully edifying collection of essays which, not surprisingly, my students in courses on devotional classics have repeatedly selected as their favorite."(9)

We move now to consider the devotional theology of Thomas R. Kelly.

Searching for an adequate life was the long-range goal of his short earthly existence. He began with the assumption of God's real being and activity, and moved ahead to assert that our great need is to experience God as active in the world at large and within human hearts particularly. God is more than nature, more than compassionate service, more than Scripture, and the claims of God must be upheld against all forms of mediocrity. This requires careful scholarship without rationalism and immediate experience without quietism.

The call to immediacy sounds again and again through his writings, no matter the period of his life in which they were composed. God is the Life, the Light, the Center of all things, and is to be sought within and experienced within. As Kelly described it, "...God Himself is active, is dynamic, is here, is brooding over us all, is prompting and instructing us within, in amazing immediacy. This is not something to believe, it is something to experience, in the solemn, sacred depths of our beings" (EP 90).

This historic Quaker note is heard in the words Kelly mailed off on the morning of his last day:

"Deep within us all there is an amazing inner sanctuary of the soul, a holy place, a Divine Center, a speaking Voice, to which we may continuously return .... It is the Shekinah of the soul, the Presence in the midst .... And He is within us all" (TD 29).

Kelly has less to say about humanity and sin than about God and divine reality. As he sees it, the West has been mistaken in thinking that our problems are basically external and environmental. The real roots of human problems lie buried within, whence they manifest themselves in behavior that is distracted, fragmented, and therefore destructive. As individuals, "We are trying to be several selves at once, without all our selves being organized by a single, mastering Life within us" (TD 114). According to him, we might be diagnosed as spiritually schizophrenic. Each person possesses by nature a demonic element and also an unformed Christ within. The Church has been too quick to identify the demonic as true human nature while rejecting or forgetting the Christ within (EP 40f.).

Kelly holds that there are many seekers after truth and life in our day, at least as many as in the days of George Fox. And how is the search for God to be carried on? Kelly is clear in positing that the initiative in human salvation comes from God -- "God the initiator;" as he put it, "God the aggressor, God the seeker, God the stirrer into life, God the ground of our obedience, God the giver of the power to become children of God" (TD 52). This theme he reiterates several times in his essays (TD 29, 41, 51f., 97,124). It is important to note that, in keeping with the Quaker emphasis, he believes God does not initiate the application of salvation from outside human experience. Rather, the true Light that enlightens every one in the world is already within by virtue of their creation (cf. John 1:9):

Did you start the search for Him? He started you on the search for Him, and lovingly, anxiously, tenderly guides you to Himself. You knock on heaven's gate, because He has already been standing at the door and knocking within you, disquieting you and calling you to arise and seek your Father's house. It is as St. Augustine says: He was within, and we mistakenly sought Him without. It isn't a matter of believing in the Inner Light, it is a matter of yielding your lives to Him (EP 105; cf. 19f., 22, 59, 101, 115).

The claims of this initiating God are totalitarian, and the human response to them can be nothing less than "true decidedness of life orientation... thoroughly, wholly, in every department and without reserve" (EP 16). "He asks all, but He gives all" (TD 50). It is important for Kelly that Christian faith-commitment not be misunderstood as an emotional high or an ecstatic experience. For him the obedience of the will is central and crucial. "Let us be quite clear," he writes,that mystical exaltation is not essential to religious dedication and to every occurrence of religious worship. Many a [person] professes to be without a shred of mystical elevation, yet is fundamentally a heaven-dedicated soul .... The crux of religious living lies in the will, not in transient and variable states. Where the will to will God's will is present, there is a child of God (EP 87f., quoted also in TD 24f.).Like Saint Augustine one asks not for greater certainty of God but only for more steadfastness in Him (TD 57).

DISCIPLESHIP AND WORSHIP

The total life-dedication which issues in holy obedience will have the purity of God as its mastering passion.

"I would plead for holy lives, such as arise out of fellowship with Him, lives not secular and boisterously worldly in backslapping camaraderie, in the effort to make religion appealing to the [person] who wants a little religion, but not too much. But lives that are like those of the disciples, of whom it was said, 'They took notice of them, that they had been with Jesus."' (EP 113f.).

On this basis Kelly criticized the Society of Friends of his day for a cooling down, a shrinking back, a delicacy not found either in Scripture or in their founders. It was, he said, an invasion of secularity into the church (EP 112f., 116f.).

"Even the Quaker preaching upon the immediacy of Divine Presence, for which there is no substitute in religious learnedness or endeavor, even this preaching has been a thing for many Quakers to believe in, not a gateway into the experience of God Himself" (EP 111).

One shape that this life takes is that of worship and prayer, whether public or private:

An invariable element in the experience of Now is that of unspeakable and exquisite joy, peace, serene release. A new song is put into our mouths .... But the main point is not that a new song is put into our mouths; the point is that a new song is put into our mouths. We sing, yet not we, but the Eternal sings in us ...(TD 97f.).We re-read the poets and the saints, and... the Scriptures, with no thought of pious exercise, but in order to find more friends for the soul .... Particularly does devotional literature become illuminated, for the Imitation of Christ, and Augustine's Confessions, and Brother Lawrence's Practice of the Presence of God speak the language of the souls who live at the Center (TD 82).

The topics of Church and world drew out of Kelly some of his most eloquent writing. "When we are drowned in the overwhelming seas of the love of God," he wrote,we find ourselves in a new and particular relation to a few of our fellows. The relation is so surprising and so rich that we despair of finding a word glorious enough and weighty enough to name it. The word Fellowship is discovered, but the word is pale and thin in comparison with... the experience which it would designate. For a new kind of life-sharing and of love has arisen of which we had had only dim hints before (TD 77).

Kelly took very seriously the biblical concept of koinonia:The disclosure of God normally brings the disclosure of the Fellowship. We don't create it deliberately; we find it and we find ourselves increasingly within it as we find ourselves increasingly within Him. It is the holy matrix of 'the communion of the saints; the body of Christ which is His church .... Yet can one be surprised at being at home? (TD 80f.).

For Kelly it is important that this "new and particular relation" does not result in escape from the world or in retreat from its suffering. Instead, "the experience of divine Presence contains within it not only a sense of being energized from a heavenly Beyond; it contains also a sense of being energized toward an earthly world" (EP 25f.).We are torn loose from earthly attachments and ambitions contemptus mundi. And we are quickened to a divine but painful concern for the world -- amor mundi. He plucks the world out of our hearts, loosening the chains of attachment. And He hurls the world into our hearts, where we and He together carry it in infinitely tender love (TD 47).

This note of compassion, of tenderness, sounds repeatedly through Kelly's scattered essays. Reflecting on his experiences in Hitler's Germany, he writes,For a few agonized moments we may seem to be given to stand within the heart of the World-Father and feel the infinite sufferings of love toward all the Father's children. And pain inflicted on them becomes pain inflicted on ourselves. Were the experience not also an experience suffused with radiant peace and power and victory, as well as tragedy, it would be unbearable (EP 29).One might almost say we become cosmic mothers, tenderly caring for all .... Would that we could relove the whole world! (TD 990.

There is a sense in which, in this terrible tenderness, we become one with God and bear in our quivering souls the sins and burdens, the benightedness and the tragedy of the creatures of the whole world, and suffer in their suffering, and die in their death (TD 107).

Kelly acknowledged quite frankly that there is a suffering in the world so awesome, so vast, that it can only be termed unremovable. "I must confess," he wrote, "that, on human judgment, the world tasks we face are appalling -- well-nigh hopeless." (TD 64). "An awful solemnity is upon the earth, for the last vestige of earthly security is gone. It has always been gone, and religion has always said so, but we haven't believed it. There is an inexorable amount of suffering in all life, blind, aching, unremovable, not new but only terribly intensified in these days" (TD 68ff.)."But there is also removable suffering;" as Kelly put it:The Cross as dogma is painless speculation; the Cross as lived suffering is anguish and glory. I dare not urge you to your Cross. But He, more powerfully, speaks within you and me, to our truest selves, in our truest moments, and disquiets us with the world's needs. By inner persuasions He draws us to a few very definite tasks, our tasks, God's burdened heart particularizing His burdens in us (TD 710 .

...He, working within us, portions out His vast concern into bundles, and lays on each of us our portion. These become our tasks (TD 123).

It was important to Kelly that Christians become responsible to and for the specific concerns God places within them. Good intentions do not substitute for concrete action that addresses specifics -- action prompted by immediate spiritual guidance.When we say Yes or No to calls for service on the basis of heady decisions, we have to give reasons, to ourselves and to others. But when we say Yes or No to calls, on the basis of inner guidance... we have no reason to give, except one -- the will of God as we discern it. Then we have begun to live in guidance. And I find He never guides us into an intolerable scramble of panting feverishness. The Cosmic Patience becomes, in part, our patience, for after all God is at work in the world. It is not we alone who are at work in the world, frantically finishing a work to be offered to God (TD 123f.).

Kelly says little about the future except to comment on time and eternity.Were earthly life to end in this moment, all would be well. For this Here, this Now, is not a mathematical point in the stream of Time; it is swollen with Eternity, it is the dwelling place of God Himself. We ask no more; we are at home. Thou who hast made us for Thyself dost in each moment give us our rest in Thee. Each moment has a Before and After; but still deeper, it has Eternity, and we have tasted it and are satisfied (EP 21f.).Life from the Center is a life of unhurried peace and power. It is simple. It is serene. It is amazing. It is triumphant. It is radiant. It takes no time, but it occupies all our time. And it makes our life programs new and overcoming. We need not get frantic. He is at the helm. And when our little day is done we lie down quietly in peace, for all is well (TD 124).

ASSESSMENT

We may now attempt a summary analysis of the devotional theology of Thomas Kelly. In assaying the contents of Kelly's writings, it is imperative that we not seek for a fully-orbed theological statement. Although he was seminary trained as well as philosophically disciplined, Kelly's writings are occasional pieces, always assuming familiarity with Quaker thought and life. At the same time, he displayed the gifts of being able to transcend the limits of denominationalism (EP 45) and to communicate that broader vision through the spoken and written word (EP 7).

In the area of theology proper, Kelly adopts a traditional Quaker stance, emphasizing the inner light, the living Christ, the prevenient Spirit resident within every person. According to this doctrine, we search vainly in the world or in others for God. Instead, we need a turning inward to the depths of our being and a cultivation of the God who is already active there. The imperative of personal experience of this God is strong and consistent in all that Kelly wrote.(10)

In anthropology, he "employs always a positive psychology, founded upon the Quaker high estimate of human nature and potential." (11) Simultaneously, he believes humanity has been marred by sin, and the result is that we do not seek God rightly or we try to flee from the hound of heaven. We are -- to use Kelly's terms -- fragmented, shallow, and disorganized, needing to become settled, coordinated, and unselfed. The crux of the matter is the human will which can, if it chooses, discern and obey the will of God. Taken alone, such a concept sounds Pelagian, but the initiative for Kelly is always divine, so that we are in truth responders and followers and disciples.

No clear line of transition in soteriology is prescribed by Kelly, no outward repentance is called for. Instead there may be, in his view, an awkward turning toward the light and a rather groping start at walking in it. Eventually there should come a kind of living in which we function adequately on two levels at once: the upper, outer order of life which is visible to others, and the deep, inner level where true reality dwells. The goal is continuously refreshed immediacy, and this immediacy will express itself in both worship and service, in work as well as prayer.

Kelly's ecclesiology describes the Church as the company of those so committed, the blessed community in which we are at home in the interconnectedness of those who are loved and who love in return. In this fellowship the usual symbols of Christian faith (e.g., language, creeds, sacraments) may give way to such "recreated symbols" as lived-out behaviors and filled silence. Here the practice of the presence of God is ongoing daily business. Scripture and devotional literature become staples for the journey which takes the form of dual vertical and horizontal dimensions. The most difficult aspects come in maintaining holy obedience to the God who asks all, and in entering suffering for the sake of God's world.

At the end lies death and the experience of a life where work and worship coalesce in a single reality. As for the world, Kelly does not intimate whether it may continue forever or end with bang or whimper. What matters -- and, for him, all that matters -- is the ongoing encounter with the God who addresses us through the living Christ within our truest selves.

CONCLUSION: THE DIVINE INVASION

Several closing comments about the work of Kelly may be in order. Like all substantial devotional writing, it needs to be read slowly, thoughtfully, and repeatedly. At first glance some of his language may sound dissonant. God for example, is referred to as the Presence, the Center, the Silence, the Abyss, the Seed. Those already acquainted with Quaker devotion or the mystical authors of the Church should have no difficulty with the language. Readers may, in fact, be pleased that Kelly uses almost none of the technical vocabulary normally found in philosophers and theologians.

A second and related comment concerns Kelly's use of Scripture, which is more indirect than direct. Ever the Quaker, he relies on a principle enunciated by George Fox: "The Lord has come to teach His people Himself." Revelation therefore is a present experience, and Scripture is to be understood from within the life of God. Kelly's bent to rigorous scholarship does not eliminate matters of grammatical-historical exegesis but, to use Reformation terminology, the inner witness of the Spirit takes precedence.

Finally, upon first reading, one may conclude that Jesus of Nazareth occupies little place in Kelly's thought, for he seldom refers to the events of Bethlehem, Galilee, Calvary, or Pentecost. Incarnation and atonement are scarcely mentioned. This is not because Kelly was oblivious to them or uncaring of them, but because he had adopted from study and personal experience the view of the living and written Word already described. In one striking passage, however, he does speak of the significance of Jesus:

In the dawning experience of the living Christ, the life, the teaching, and particularly the Cross and the triumph of Jesus of Nazareth become indescribably vivid and significant. For in Him the Divine Invasion... has taken place as never before, nor since, complete .... And although we understand Him in part, through the Living Christ, yet we do not understand all. For the communion of Love and Suffering... and victory on the Cross contains the secret which leads back into the very nature of God Himself (EP 31f.).In so saying, Thomas Kelly had come home. His search for an adequate life was fulfilled and, a half-century later, his description remains true and relevant.NOTES- Richard M. Kelly, Thomas Kelly: A Biography (New York: Harper & Row, 1966), p. 122.

- D. Elton Trueblood, The People Called Quakers (New York: Harper & Row, 1966), p. 222.

- Almost all of Thomas Kelly's published works are to be found in two volumes, 1] A Testament of Devotion (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1941), hereafter abbreviated TD, and 2] The Eternal Promise (New York: Harper & Row, 1966), hereafter abbreviated EP. Cf. the one item by Kelly not included in TD or EP: 3] "The Reality of the Spiritual World" in The Pendle Hill Reader, ed. Herrymon Maurer, Essay Index Reprint Series (Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, n.d.), pp. 1-40. It was a lecture first published in Great Britain in 1944.

- Kelly suffered from hay fever so severe that it usually left him bedfast, a sinus infection which required surgery, kidney stones at the age of forty, and, at almost forty-two, a nervous breakdown (see TD 15; Richard Kelly op. cit., p. 69).

- Ibid., pp. 91f.

- Douglas V. Steere, A Testament of Devotion, Living Selections from the Great Devotional Classics (Nashville: The Upper Room, 1955), p. 5.

- Elton Trueblood, The New Man for Our Time (New York: Harper & Row, 1970), p. 63. Trueblood includes Kelly's work in a list of classics for the nurture of Christian spirituality. The other authors in Trueblood's list are Augustine, Thomas à Kempis, Lancelot Andrewes, John Donne, Blaise Pascal, John Woolman, and William Law.

- Richard J. Foster, Celebration of Discipline: The Path to Spiritual Growth, rev. ed. (New York: Harper & Row, 1988), pp. 27, 45, 72, 80, 128, 164; Freedom of Simplicity (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1981), pp. 5, 78, 86, 87, 103.

- E. Glenn Hinson (ed.), The Doubleday Devotional Classics, Volume III (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, 1978), p. 165. Hinson's introduction to Kelly's life and work (pp. 165-81) is an outstanding condensation of the known data about him together with Hinson's discerning interpretation.

- "Like Rufus Jones, Thomas Kelly interpreted Quakerism as fundamentally empirical. It is not enough, he insisted, to believe; we must actually experience the love of God .... His words came out of what can only be called a baptism by fire. He was enkindled and he burned with a fast flame" (Elton Trueblood in Herrymon Maurer, op. cit., p. xi).

- Hinson, op. cit., p. 161.

Thomas R. Kelly, “The Record of the Class of 1914.” Courtesy of Quaker and Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, Pa.

Thomas R. Kelly, “The Record of the Class of 1914.” Courtesy of Quaker and Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, Pa.