The Paradox of Cuban Agriculture

When Cuba faced the shock of lost trade relations with the Soviet Bloc in the early 1990s, food production initially collapsed due to the loss of imported fertilizers, pesticides, tractors, parts, and petroleum. The situation was so bad that Cuba posted the worst growth in per capita food production in all of Latin America and the Caribbean. But the island rapidly re-oriented its agriculture to depend less on imported synthetic chemical inputs, and became a world-class case of ecological agriculture.1 This was such a successful turnaround that Cuba rebounded to show the best food production performance in Latin America and the Caribbean over the following period, a remarkable annual growth rate of 4.2 percent per capita from 1996 through 2005, a period in which the regional average was 0 percent.2

Much of the production rebound was due to the adoption since the early 1990s of a range of agrarian decentralization policies that encouraged forms of production, both individual as well as cooperative—Basic Units of Cooperative Production (UBPC) and Credit and Service Cooperatives (CCS). Moreover, recently the Ministry of Agriculture announced the dismantling of all “inefficient State companies” as well as support for creating 2,600 new small urban and suburban farms, and the distribution of the use rights (in usufruct) to the majority of estimated 3 million hectares of unused State lands. Under these regulations, decisions on resource use and strategies for food production and commercialization will be made at the municipal level, while the central government and state companies will support farmers by distributing necessary inputs and services.3 Through the mid-1990s some 78,000 farms were given in usufruct to individuals and legal entities. More than 100,000 farms have now been distributed, covering more than 1 million hectares in total. These new farmers are associated with the CCS following the campesinoproduction model. The government is busy figuring out how to accelerate the processing of an unprecedented number of land requests.4

The land redistribution program has been supported by solid research- extension systems that have played key roles in the expansion of organic and urban agriculture and the massive artisanal production and deployment of biological inputs for soil and pest management. The opening of local agricultural markets and the existence of strong grassroots organisations supporting farmers—for example, the National Association of Small Scale Farmers (ANAP, Asociación Nacional de Agricultores Pequeños), the Cuban Association of Animal Production (ACPA, Asociación Cubana de Producción Animal), and the Cuban Association of Agricultural and Forestry Technicians (ACTAF, Asociación Cubana de Técnicos Agrícolas y Forestales)—also contributed to this achievement.

But perhaps the most important changes that led to the recovery of food sovereignty in Cuba occurred in the peasant sector which in 2006, controlling only 25 percent of the agricultural land, produced over 65 percent of the country’s food.5 Most peasants belong to the ANAP and almost all of them belong to cooperatives. The production of vegetables typically produced by peasants fell drastically between 1988 to 1994, but by 2007 had rebounded to well over 1988 levels (see Table 1). This production increase came despite using 72 percent fewer agricultural chemicals in 2007 than in 1988. Similar patterns can be seen for other peasant crops like beans, roots, and tubers.

Cuba’s achievements in urban agriculture are truly remarkable—there are 383,000 urban farms, covering 50,000 hectares of otherwise unused land and producing more than 1.5 million tons of vegetables with top urban farms reaching a yield of 20 kg/m2 per year of edible plant material using no synthetic chemicals—equivalent to a hundred tons per hectare. Urban farms supply 70 percent or more of all the fresh vegetables consumed in cities such as Havana and Villa Clara.

Table 1. Changes in Crop Production and Agrochemical Use

Crop | Percent production change | Percent change in agrochemical use | |

1988 to 1994 | 1988 to 2007 | 1988 to 2007 | |

General vegetables | -65 | +145 | -72 |

Beans | -77 | +351 | -55 |

Roots and tubers | -42 | +145 | -85 |

Source: Peter Rosset, Braulio Machín-Sosa, Adilén M. Roque-Jaime, and Dana R. Avila-Lozano, “The Campesino-to-Campesino Agroecology Movement of ANAP in Cuba,” Journal of Peasant Studies 38 (2011): 161-91.

All over the world, and especially in Latin America, the island’s agroecological production levels and the associated research efforts along with innovative farmer organizational schemes have been observed with great interest. No other country in the world has achieved this level of success with a form of agriculture that uses the ecological services of biodiversity and reduces food miles, energy use, and effectively closes local production and consumption cycles. However, some people talk about the “Cuban agriculture paradox”: if agroecological advances in the country are so great, why does Cuba still import substantial amounts of food? If effective biological control methods are widely available and used, why is the government releasing transgenic plants such as Bt crops that produce their own pesticide using genes derived from bacteria?

An article written by Dennis Avery from the Center for Global Food Issues at the Hudson Institute, “Cubans Starve on Diet of Lies,” helped fuel the debate around the paradox. He stated:

The Cubans told the world they had heroically learned to feed themselves without fuel or farm chemicals after their Soviet subsidies collapsed in the early 1990s. They bragged about their “peasant cooperatives,” their biopesticides and organic fertilizers. They heralded their earthworm culture and the predator wasps they unleashed on destructive caterpillars. They boasted about the heroic ox teams they had trained to replace tractors. Organic activists all over the world swooned. Now, a senior Ministry of Agriculture official has admitted in the Cuban press that 84 percent of Cuba’s current food consumption is imported, according to our agricultural attaché in Havana. The organic success was all a lie.6

Avery has used this misinformation to promote a campaign discrediting authors who studied and informed about the heroic achievements of Cuban people in the agricultural field: he has accused these scientists of being communist liars.

The Truth About Food Imports in Cuba

Avery referred to statements of Magalys Calvo, then Vice Minister of the Economy and Planning Ministry, who said in February 2007 that 84 percent of items “in the basic food basket” at that time were imported. However, these percentages represent only the food that is distributed through regulated government channels by means of a ration card. Overall data show that Cuba’s food import dependency has been dropping for decades, despite brief upturns due to natural and human-made disasters. The best time series available on Cuban food import dependency (see Chart 1) shows that it actually declined between 1980 and 1997, aside from a spike in the early 1990s, when trade relations with the former Socialist Bloc collapsed.7

Chart 1. Cuba Food Import Dependency, 1980–1997

Source: José Alvarez, The Issue of Food Security in Cuba, University of Florida Extension Report FE483, downloaded July 20, 2011 from http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/FE/FE48300.pdf.

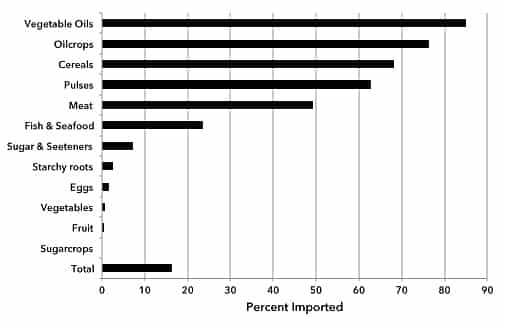

However, Chart 2 indicates a much more nuanced view of Cuba’s agricultural strengths and weaknesses after more than a decade of technological bias toward ecological farming techniques. Great successes have clearly been achieved in root crops (a staple of the Cuban diet), sugar and other sweeteners, vegetables, fruits, eggs, and seafood. Meat is an intermediate case, while large amounts of cooking oil, cereals, and legumes (principally rice and wheat for human consumption, and corn and soybeans for livestock) continue to be imported. The same is true for powdered milk, which does not appear on the graph. Total import dependency, however, is a mere 16 percent—ironically the exact inverse of the 84 percent figure cited by Avery. It is also important to mention that twenty-three other countries in the Latin American-Caribbean region are also net food importers.8

Chart 2. Import Dependence For Selected Foods, 2003

Source: Calculated from FAO Commodity Balances, Cuba, 2003, http://faostat.fao.org.

There is considerable debate concerning current food dependency in Cuba. Dependency rose in the 2000s as imports from the United States grew and hurricanes devastated its agriculture. After being hit by three especially destructive hurricanes in 2008, Cuba satisfied national needs by importing 55 percent of its total food, equivalent to approximately $2.8 billion. However, as the world food price crisis drives prices higher, the government has reemphasized food self-sufficiency. Regardless of whether food has been imported or produced within the country, it is important to recognize that Cuba has been generally able to adequately feed its people. According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Cuba’s average daily per capita dietary energy supply in 2007 (the last year available) was over 3,200 kcal, the highest of all Latin American and Caribbean nations.9

Different Models: Agroecology versus Industrial Agriculture

Under this new scenario the importance of contributions of ANAP peasants to reducing food imports should become strategic, but is it? Despite the indisputable advances of sustainable agriculture in Cuba and evidence of the effectiveness of alternatives to the monoculture model, interest persists among some leaders in high external input systems with sophisticated and expensive technological packages. With the pretext of “guaranteeing food security and reducing food imports,” these specific programs pursue “maximization” of crop and livestock production and insist on going back to monoculture methods—and therefore dependent on synthetic chemical inputs, large scale machinery, and irrigation—despite proven energy inefficiency and technological fragility. In fact, many resources are provided by international cooperation (i.e., from Venezuela) dedicated to “protect or boost agricultural areas” where a more intensive agriculture is practiced for crops like potatoes, rice, soybean, and vegetables. These “protected” areas for large-scale, industrial-style agricultural production represent less than 10 percent of the cultivated land. Millions of dollars are invested in pivot irrigation systems, machinery, and other industrial agricultural technologies: a seductive model which increases short-term production but generates high long-term environmental and socioeconomic costs, while replicating a model that failed even before 1990.

Last year it was announced that the pesticide enterprise “Juan Rodríguez Gómez” in the municipality of Artemisa, Havana, will produce some 100,000 liters of the herbicide glyphosate in 2011.10 In early 2011 a Cuban TV News program informed the population about the Cubasoy project. The program, “Bienvenida la Soya,” reported that “it is possible to transform lands that over years were covered by marabú [a thorny invasive leguminous tree] with soybean monoculture in the south of the Ciego de Ávila province.” Supported by Brazilian credits and technology, the project covers more than 15,000 hectares of soybean grown in rotation with maize and aims at reaching 40,500 hectares in 2013, with a total of 544 center pivot irrigation systems installed by 2014. Soybean yields rank between 1.2 tons per hectare (1,100 lbs per acre) under rainfed conditions and up to 1.97 tons per hectare (1,700 lbs per acre) under irrigation. It is not clear if the soybean varieties used are transgenic, but the maize variety is the Cuban transgenic FR-Bt1. Ninety percent of machinery is imported from Brazil—“large tractors, direct seeding machines, and equipment for crop protection”—and considerable infrastructure investments have been made for irrigation, roads, technical support, processing, and transport.

The Debate Over Transgenic Crops

Cuba has invested millions in biotechnological research and development for agriculture through its Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (CIGB) and a network of institutions across the country. Cuban biotechnology is free from corporate control and intellectual property-right regimes that exist in other countries. Cuban biotechnologists affirm that their biosafety system sets strict biological and environmental security norms. Given this autonomy and advantages biotechnological innovations could efficiently be applied to solve problems such as viral crop diseases or drought tolerance for which agroecological solutions are not yet available. In 2009 the CIGB planted in Yagüajay, Sancti Spiritus, three hectares of genetically modified corn (transgenic corn FR-Bt1) on an experimental basis. This variety is supposed to suppress populations of the damaging larval stage of the “palomilla del maíz” moth (Spodoptera frugiperda, also known as the fall armyworm). By 2009 a total of 6,000 hectares were planted with the transgenic (also referred to as genetically modified, or GM) variety across several provinces. From an agroecological perspective it is perplexing that the first transgenic variety to be tested in Cuba is Bt corn, given that in the island there are so many biological control alternatives to regulate lepidopteran pests. The diversity of local maize varieties include some that exhibit moderate-to-high levels of pest resistance, offering significant opportunities to increase yields with conventional plant breeding and known agroecological management strategies. Many centers for multiplication of insect parasites and pathogens (CREEs, Centros de Reproducción de Entomófagos y Entomopatógenos) produce Bacillus thuringiensis (a microbial insecticide) and Trichogramma (small wasps), both highly effective against moths such as the palomilla. In addition, mixing corn with other crops such as beans or sweet potatoes in polycultures produces significantly less pest attack than maize grown in monocultures. This also increases the land equivalent ratio (growing more total crops in a given area of land) and protects the soil.

When transgenic Bt maize was planted in 2008 as a test crop, researchers and farmers from the agroecological movement expressed concern. Several people warned that the release of transgenic crops endangered agrobiodiversity and contradicted the government’s own agricultural production plans by diverting the focus from agroecological farming that had been strategically adopted as a policy in Cuba. Others felt that biotechnology was geared towards the interests of the multinational corporations and the market. Taking into account its potential environmental and public health risks, it would be better for Cuba to continue emphasizing agroecological alternatives that have proven to be safe and have allowed the country to produce food under difficult economic and climatic circumstances.

The main demonstrated advantage of GM crops has been to simplify the farming process, allowing farmers to work more land. GM crops that resist herbicides (such as “Roundup Ready” corn and soybeans) and that produce their own insecticide (such as Bt corn) generally do not yield any more than comparable non-GM crops. However, using these GM crops along with higher levels of mechanization (especially larger tractors) have now made it possible for the size of a family corn and soybean farm in the U.S. Midwest to increase from around 240 hectares (600 acres) to around 800 hectares (2,000 acres).

In September 2010 a meeting of experts concerned about transgenic crops was convened with board and staff members from the National Center for Biological Security and the Office for Environmental Regulation and Nuclear Security (Centro Nacional de Seguridad Biológica and the Oficina de Regulación Ambiental y Seguridad Nuclear), institutions entrusted with licensing GM crops. The experts issued a statement calling for a moratorium on GM crops until more information was available and society has a chance to debate the environmental and health effects of the technology. However, until now there has been no response to this request. One positive outcome of the year-long debate on the inconsistency of planting FR-Bt1 transgenic corn in Cuba was the open recognition by the authorities of the potential devastating consequences of GM crops for the small farmer sector. Although it appears that the use of transgenic corn will be limited exclusively to the areas of Cubasoy and other conventional areas under strict supervision, this effort is highly questionable.11

The Paradox’s Outcome—What Does the Future Hold?

The instability in international markets and the increase in food prices in a country somewhat dependent on food imports threatens national sovereignty. This reality has prompted high officials to make declarations emphasizing the need to prioritize food production based on locally available resources.12 It is in fact paradoxical that, to achieve food security in a period of economic growth, most of the resources are dedicated to importing foods or promoting industrial agriculture schemes instead of stimulating local production by peasants. There is a cyclical return to support conventional agriculture by policy makers when the financial situation improves, while sustainable approaches and agroecology, considered as “alternatives,” are only supported under scenarios of economic scarcity. This cyclical mindset strongly undermines the advances achieved with agroecology and organic farming since the economic collapse in 1990.

Cuban agriculture currently experiences two extreme food-production models: an intensive model with high inputs, and another, beginning at the onset of the special period, oriented towards agroecology and based on low inputs. The experience accumulated from agroecological initiatives in thousands of small-and-medium scale farms constitutes a valuable starting point in the definition of national policies to support sustainable agriculture, thus rupturing with a monoculture model prevalent for almost four hundred years. In addition to Cuba being the only country in the world that was able to recover its food production by adopting agroecological approaches under extreme economic difficulties, the island exhibits several characteristics that serve as fundamental pillars to scale up agroecology to unprecedented levels:

Cuba represents 2 percent of the Latin American population but has 11 percent of the scientists in the region. There are about 140,000 high-level professionals and medium-level technicians, dozens of research centres, agrarian universities and their networks, government institutions such as the Ministry of Agriculture, scientific organizations supporting farmers (i.e. ACTAF), and farmers organizations such as ANAP.

Cuba has sufficient land to produce enough food with agroecological methods to satisfy the nutritional needs of its eleven million inhabitants.13 Despite soil erosion, deforestation, and loss of biodiversity during the past fifty years—as well as during the previous four centuries of extractive agriculture—the country’s conditions remain exceptionally favorable for agriculture. Cuba has six million hectares of fairly level land and another million gently sloping hectares that can be used for cropping. More than half of this land remains uncultivated, and the productivity of both land and labor, as well as the efficiency of resource use, in the rest of this farm area are still low. If all the peasant farms (controlling 25 percent of land) and all the UBPC (controlling 42 percent of land) adopted diversified agroecological designs, Cuba would be able to produce enough to feed its population, supply food to the tourist industry, and even export some food to help generate foreign currency. All this production would be supplemented with urban agriculture, which is already reaching significant levels of production.

About one third of all peasant families, some 110,000 families, have joined ANAP within its Farmer to Farmer Agroecological Movement (MACAC, Movimiento Agroecológico Campesino a Campesino). It uses participatory methods based on local peasant needs and allows for the socialization of the rich pool of family and community agricultural knowledge that is linked to their specific historical conditions and identities. By exchanging innovations among themselves, peasants have been able to make dramatic strides in food production relative to the conventional sector, while preserving agrobiodiversity and using much lower amounts of agrochemicals.

Observations of agricultural performance after extreme climatic events in the last two decades have revealed the resiliency of peasant farms to climate disasters. Forty days after Hurricane Ike hit Cuba in 2008, researchers conducted a farm survey in the provinces of Holguin and Las Tunas and found that diversified farms exhibited losses of 50 percent compared to 90 to 100 percent in neighboring farms growing monocultures. Likewise agroecologically managed farms showed a faster productive recovery (80 to 90 percent forty days after the hurricane) than monoculture farms.14 These evaluations emphasize the importance of enhancing plant diversity and complexity in farming systems to reduce vulnerability to extreme climatic events, a strategy entrenched among Cuban peasants.

Most of the production efforts have been oriented towards reaching food sovereignty, defined as the right of everyone to have access to safe, nutritious, and culturally appropriate food in sufficient quantity and quality to sustain a healthy life with full human dignity. However, given the expected increase in the cost of fuel and inputs, the Cuban agroecological strategy also aims at enhancing two other types of sovereignties. Energy sovereignty is the right for all people to have access to sufficient energy within ecological limits from appropriate sustainable sources for a dignified life. Technological sovereignty refers to the capacity to achieve food and energy sovereignty by nurturing the environmental services derived from existing agrobiodiversity and using locally available resources.

Elements of the three sovereignties—food, energy, and technology—can be found in hundreds of small farms, where farmers are producing 70–100 percent of the necessary food for their family consumption while producing surpluses sold to the market, allowing them to obtain income (for example, Finca del Medio, CCS Reinerio Reina in Sancti Spiritus; Plácido farm, CCS José Machado; Cayo Piedra, in Matanzas, belonging to CCS José Martí; and San José farm, CCS Dionisio San Román in Cienfuegos). These levels of productivity are obtained using local technologies such as worm composting and reproduction of beneficial native microorganisms together with diversified production systems such as polycultures, rotations, animal integration into crop farms, and agroforestry. Many farmers are also using integrated food/energy systems and generate their own sources of energy using human and animal labor, biogas, and windmills, in addition to producing biofuel crops such as jatrophaintercropped with cassava.15

Conclusions

A rich knowledge of agroecology science and practice exists in Cuba, the result of accumulated experiences promoted by researchers, professors, technicians, and farmers supported by ACTAF, ACPA, and ANAP. This legacy is based on the experiences within rural communities that contain successful “agroecological lighthouses” from which principles have radiated out to help build the basis of an agricultural strategy that promotes efficiency, diversity, synergy, and resiliency. By capitalizing on the potential of agroecology, Cuba has been able to reach high levels of production using low amounts of energy and external inputs, with returns to investment on research several times higher than those derived from industrial and biotechnological approaches that require major equipment, fuel, and sophisticated laboratories.

The political will expressed in the writings and discourses of high officials about the need to prioritize agricultural self-sufficiency must translate into concrete support for the promotion of productive and energy-efficient initiatives in order to reach the three sovereignties at the local (municipal) level, a fundamental requirement to sustain a planet in crisis.

By creating more opportunities for strategic alliances between ANAP, ACPA, ACTAF, and research centers, many pilot projects could be launched in key municipalities, testing different agroecological technologies that promote the three sovereignties, as adapted to each region’s special environmental and socioeconomic conditions. These initiatives should adopt the farmer-to-farmer methodology that transcends top-down research and extension paradigms, allowing farmers and researchers to learn and innovate collectively. The integration of university professors and students in such experimentation and evaluation processes would enhance scientific knowledge for the conversion to an ecologically based agriculture. It would also help improve agroecological theory, which would in turn benefit the training of future generations of professionals, technicians, and farmers.

The agroecological movement constantly urges those Cuban policy makers with a conventional, Green Revolution, industrial farming mindset to consider the reality of a small island nation facing an embargo and potentially devastating hurricanes. Given these realities, embracing agroecological approaches and methods throughout the country’s agriculture can help Cuba achieve food sovereignty while maintaining its political autonomy.

Notes

- ↩ Peter Rosset and Medea Benjamin, eds., The Greening of the Revolution (Ocean Press: Melbourne, Australia, 1994); Fernando Funes, et. al., eds., Sustainable Agriculture and Resistance (Oakland: Food First Books, 2002); Braulio Machín-Sosa, et. al., Revolución Agroecológica (ANAP: La Habana, 2010).

- ↩ Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), The State of Food and Agriculture 2006(Rome: FAO, 2006), http://fao.org.

- ↩ MINAG (Ministerio de la Agricultura), Informe del Ministerio de la Agricultura a la Comisión Agroalimentaria de la Asamblea Nacional, May 14, 2008 (MINAG: Havana, Cuba, 2008).

- ↩ Ana Margarita González, “Tenemos que dar saltos cualitativos,” Interview with Orlando Lugo Fonte, Trabajadores, June 22, 2009, 6.

- ↩ Raisa Pagés, “Necesarios cambios en relaciones con el sector cooperativo-campesino,” Granma, December 18, 2006, 3.

- ↩ Dennis T. Avery, “Cubans Starve on Diet of Lies,” April 2, 2009, http://cgfi.org.

- ↩ Fernando Funes, Miguel A. Altieri, and Peter Rosset, “The Avery Diet: The Hudson’s Institute Misinformation Campaign Against Cuban Agriculture,” May 2009, http://globalalternatives.org.

- ↩ FAO, Ibid.

- ↩ FAOSTAT Food Supply Database, http://faostat.fao.org, accessed July 28, 2011.

- ↩ René Montalván, “Plaguicidas de factura nacional,” El Habanero, November 23, 2010, 4.

- ↩ Fernando Funes-Monzote and Eduardo F. Freyre Roach, eds., Transgénicos ¿Qué se gana? ¿Qué se pierde? Textos para un debate en Cuba (Havana: Publicaciones Acuario, 2009), http://landaction.org.

- ↩ Raúl Castro, “Mientras mayores sean las dificultades, más exigencia, disciplina y unidad se requieren,” Granma, February 25, 2008, 4–6.

- ↩ Fernando Funes-Monzote, Farming Like We’re Here to Stay, PhD dissertation, Wageningen University, Netherlands, 2008.

- ↩ Braulio Machin-Sosa, et. al., Revolución Agroecológica: el Movimiento de Campesino a Campesino de la ANAP en Cuba (ANAP: La Habana, 2010).

- ↩ Fernando Funes-Monzote, et. al., “Evaluación inicial de sistemas integrados para la producción de alimentos y energía en Cuba,” Pastos y Forrajes (forthcoming, 2011).