Five precepts - Wikipedia Five precepts

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to navigationJump to searchThis article is about the five precepts in Buddhism. For Taoism, see

Five Precepts (Taoism).

Plaque with the five precepts engraved,

Lumbini, Nepal

Buddhist devotional practices

Devotional Offerings Prostration Merit-making Taking refuge Chanting Pūja Holidays Buddha's Birthday Vesak Ghost Festival Uposatha Kaṭhina Precepts Five Precepts Eight Precepts Bodhisattva vow Bodhisattva Precepts Other

Meditation Giving Texts Pilgrimage Fasting v t e Translations of

five precepts

Sanskrit pañcaśīla (

पञ्चशील), pañcaśikṣapada (

पञ्चशिक्षपद)

Pali pañcasīla, pañcasīlani,

[1] pañcasikkhāpada, pañcasikkhāpadani

[1] Burmese ပဉ္စသီလ ငါးပါးသီလ

(IPA:

[pjɪ̀ɰ̃sa̰ θìla̰ ŋá bá θìla̰])

Chinese 五戒(

Pinyin: wǔjiè)

Japanese 五戒(

rōmaji: go kai)

Khmer បញ្ចសីល, និច្ចសីល, សិក្ខាបទ៥, សីល៥

(

UNGEGN: Sel

[2])

Korean 오계五戒(

RR: ogye)

Mon သဳ မသုန်

([sɔe pəsɔn])

Sinhala පන්සිල්(pan sil

[3])

Thai เบญจศีล, ศีล ๕

(

RTGS: Benchasin, Sin Ha)

Vietnamese 五戒Ngũ giới Indonesian Pancasila Glossary of Buddhism The Five precepts (

Sanskrit: pañcaśīla;

Pali: pañcasīla) or five rules of training (

Sanskrit: pañcaśikṣapada;

Pali: pañcasikkhapada)

[4][5][note 1] is the most important system of morality for

Buddhist lay people. They constitute the basic code of

ethics to be undertaken by lay followers of Buddhism. The precepts are commitments to abstain from killing

living beings, stealing, sexual misconduct, lying and intoxication. Within the Buddhist doctrine, they are meant to develop mind and character to make progress on the path to

enlightenment. They are sometimes referred to as the

Śrāvakayāna precepts in the

Mahāyāna tradition, contrasting them with the

bodhisattva precepts. The five precepts form the basis of several parts of Buddhist doctrine, both lay and monastic. With regard to their fundamental role in Buddhist ethics, they have been compared with the

ten commandments in

Abrahamic religions[6][7] or the

ethical codes of

Confucianism. The precepts have been connected with

utilitarianist,

deontological and

virtue approaches to ethics, though by 2017, such categorization by western terminology had mostly been abandoned by scholars. The precepts have been compared with human rights because of their universal nature, and some scholars argue they can complement the concept of human rights.

The five precepts were common to the religious milieu of 6th-century BCE India, but the Buddha's focus on

awareness through the fifth precept was unique. As shown in

Early Buddhist Texts, the precepts grew to be more important, and finally became a condition for membership of the Buddhist religion. When Buddhism spread to different places and people, the role of the precepts began to vary. In countries where Buddhism had to compete with other religions, such as China, the ritual of undertaking the five precepts developed into an initiation ceremony to become a Buddhist lay person. On the other hand, in countries with little competition from other religions, such as Thailand, the ceremony has had little relation to the rite of becoming Buddhist, as many people are presumed Buddhist from birth.

Undertaking and upholding the five precepts is based on the principle of

non-harming (

Pāli and

Sanskrit: ahiṃsa). The

Pali Canon recommends one to compare oneself with others, and on the basis of that, not to hurt others. Compassion and a belief in

karmic retribution form the foundation of the precepts. Undertaking the five precepts is part of regular lay devotional practice, both at home and at the local temple. However, the extent to which people keep them differs per region and time. People keep them with an intention to develop themselves, but also out of fear of a

bad rebirth.

The first precept consists of a prohibition of killing, both humans and all animals. Scholars have interpreted Buddhist texts about the precepts as an opposition to and prohibition of capital punishment,

[8] suicide, abortion

[9][10] and euthanasia.

[11] In practice, however, many Buddhist countries still use the death penalty. With regard to abortion, Buddhist countries take the middle ground, by condemning though not prohibiting it. The Buddhist attitude to violence is generally interpreted as opposing all warfare, but some scholars have raised exceptions found in later texts.

The second precept prohibits theft and related activities such as fraud and forgery.

The third precept refers to adultery in all its forms, and has been defined by modern teachers with terms such as sexual responsibility and long-term commitment.

The fourth precept involves falsehood spoken or committed to by action, as well as malicious speech, harsh speech and gossip.

The fifth precept prohibits intoxication through alcohol, drugs or other means.

[12][13] Early Buddhist Texts nearly always condemn alcohol, and so do Chinese Buddhist post-canonical texts. Buddhist attitudes toward smoking is to abstain from tobacco due to its severe addiction.

In modern times, traditional Buddhist countries have seen revival movements to promote the five precepts. As for the West, the precepts play a major role in Buddhist organizations. They have also been integrated in

mindfulness training programs, though many mindfulness specialists do not support this because of the precepts' religious import. Lastly, many conflict prevention programs make use of the precepts.

Contents

1Role in Buddhist doctrine 2History 3Ceremonies 3.1In Pāli tradition 3.2In other textual traditions 4Principles 5Practice in general 6First precept 6.1Textual analysis 6.2In practice 7Second precept 7.1Textual analysis 7.2In practice 8Third precept 8.1Textual analysis 8.2In practice 9Fourth precept 9.1Textual analysis 9.2In practice 10Fifth precept 10.1Textual analysis 10.2In practice 11Present trends 12Theory of ethics 12.1Comparison with human rights 13See also 14Notes 15Citations 16References 17External links Role in Buddhist doctrine[

edit]

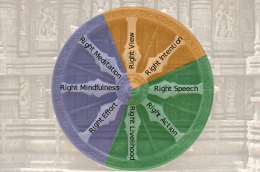

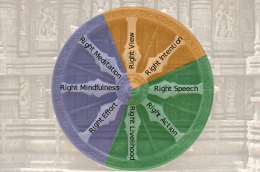

The

Noble Eightfold Path, of which the five precepts are part.

Buddhist scriptures explain the five precepts as the minimal standard of Buddhist morality.

[14] It is the most important system of morality in Buddhism, together with the

monastic rules.

[15] Śīla (Sanskrit;

Pali: sīla) is used to refer to Buddhist precepts,

[16] including the five.

[4] But the word also refers to the virtue and morality which lies at the foundation of the spiritual path to

enlightenment, which is the first of the

three forms of training on the path. Thus, the precepts are rules or guidelines to develop mind and character to make progress on the path to

enlightenment.

[4] The five precepts are part of the right speech, action and livelihood aspects of the

Noble Eightfold Path, the core teaching of Buddhism.

[4][17][note 2] Moreover, the practice of the five precepts and other parts of śīla are described as forms of

merit-making, means to create good

karma.

[19][20] The five precepts have been described as

social values that bring harmony to society,

[21][22] and breaches of the precepts described as antithetical to a harmonious society.

[23] On a similar note, in Buddhist texts, the ideal, righteous society is one in which people keep the five precepts.

[24]Comparing different parts of Buddhist doctrine, the five precepts form the basis of the

eight precepts, which are lay precepts stricter than the five precepts, similar to monastic precepts.

[4][25] Secondly, the five precepts form the first half of the

ten or eleven precepts for a

person aiming to become a Buddha (bodhisattva), as mentioned in the

Brahmajala Sūtra of the Mahāyāna tradition.

[4][26][27] Contrasting these precepts with the five precepts, the latter were commonly referred to by Mahāyānists as the

śrāvakayāna precepts, or the precepts of those aiming to become

enlightened disciples (Sanskrit: arhat; Pali: arahant) of a Buddha, but not

Buddhas themselves. The ten–eleven bodhisattva precepts presuppose the five precepts, and are partly based on them.

[28] The five precepts are also partly found in the teaching called the ten good courses of action, referred to in

Theravāda (

Pali: dasa-kusala-kammapatha) and

Tibetan Buddhism (

Sanskrit: daśa-kuśala-karmapatha;

Wylie: dge ba bcu).

[15][29] Finally, the first four of the five precepts are very similar to the

most fundamental rules of monastic discipline (Pali: pārajika), and may have influenced their development.

[30]In conclusion, the five precepts lie at the foundation of all Buddhist practice, and in that respect, can be compared with the

ten commandments in Christianity and Judaism

[6][7] or the

ethical codes of

Confucianism.

[27] History[

edit]

The five precepts were part of

early Buddhism and are common to nearly all schools of Buddhism.

[31] In early Buddhism, the five precepts were regarded as an ethic of restraint, to restrain unwholesome tendencies and thereby purify one's being to attain enlightenment.

[1][32] The five precepts were based on the pañcaśīla, prohibitions for pre-Buddhist

Brahmanic priests, which were adopted in many Indic religions around 6th century BCE.

[33][34] The first four Buddhist precepts were nearly identical to these pañcaśīla, but the fifth precept, the prohibition on intoxication, was new in Buddhism:

[30][note 3] the Buddha's emphasis on

awareness (Pali: appamāda) was unique.

[33]In some schools of ancient Indic Buddhism, Buddhist devotees could choose to adhere to only a number of precepts, instead of the complete five. The schools that would survive in later periods, however, that is Theravāda and Mahāyāna Buddhism, were both ambiguous about this practice. Some early Mahāyāna texts allow it, but some do not;

Theravāda texts do not discuss this practice at all.

[36]The prohibition on killing had motivated

early Buddhists to form a stance against animal sacrifice, a common ritual practice in ancient India.

[37][38] According to the Pāli Canon, however, early Buddhists did not adopt a vegetarian lifestyle.

[25][38]In

Early Buddhist Texts, the role of the five precepts gradually develops. First of all, the precepts are combined with a declaration of faith in the triple gem (the Buddha,

his teaching and

the monastic community). Next, the precepts develop to become the foundation of lay practice.

[39] The precepts are seen as a preliminary condition for the higher development of the mind.

[1] At a third stage in the texts, the precepts are actually mentioned together with the triple gem, as though they are part of it. Lastly, the precepts, together with the triple gem, become a required condition for the practice of Buddhism, as lay people have to undergo a formal initiation to become a member of the Buddhist religion.

[30] When Buddhism spread to different places and people, the role of the precepts began to vary. In countries in which Buddhism was adopted as the main religion without much competition from other religious disciplines, such as Thailand, the relation between the initiation of a lay person and the five precepts has been virtually non-existent. In such countries, the taking of the precepts has become a sort of ritual cleansing ceremony. People are presumed Buddhist from birth without much of an initiation. The precepts are often committed to by new followers as part of their installment, yet this is not very pronounced. However, in some countries like China, where Buddhism was not the only religion, the precepts became an ordination ceremony to initiate lay people into the Buddhist religion.

[40]

In

8th-century China, people held strict attitudes about abstinence of alcohol.

In China, the five precepts were introduced in the first centuries CE, both in their śrāvakayāna and bodhisattva formats.

[41] During this time, it was particularly Buddhist teachers who promoted abstinence from alcohol (the fifth precept), since

Daoism and other thought systems emphasized moderation rather than full abstinence. Chinese Buddhists interpreted the fifth precept strictly, even more so than in Indic Buddhism. For example, the monk

Daoshi (c. 600–683) dedicated large sections of

his encyclopedic writings to abstinence from alcohol. However, in some parts of China, such as

Dunhuang, considerable evidence has been found of alcohol consumption among both lay people and monastics. Later, from the 8th century onward, strict attitudes of abstinence led to a development of a distinct

tea culture among Chinese monastics and lay intellectuals, in which tea gatherings replaced gatherings with alcoholic beverages, and were advocated as such.

[42][43] These strict attitudes were formed partly because of the religious writings, but may also have been affected by the bloody

An Lushan Rebellion of 775, which had a sobering effect on

8th-century Chinese society.

[44] When the five precepts were integrated in Chinese society, they were associated and connected with karma,

Chinese cosmology and

medicine, a Daoist worldview, and

Confucian virtue ethics.

[45] Ceremonies[

edit]

In Pāli tradition[

edit]

In Thailand, a leading lay person will normally request the monk to administer the precepts.

In the Theravāda tradition, the precepts are recited in a standardized fashion, using

Pāli language. In Thailand, a leading lay person will normally request the monk to administer the precepts by reciting the following three times:

"Venerables, we request the five precepts and the

three refuges [i.e. the triple gem] for the sake of observing them, one by one, separately". (Mayaṃ bhante visuṃ visuṃ rakkhaṇatthāya tisaraṇena saha pañca sīlāniyācāma.)

[46]After this, the monk administering the precepts will recite a reverential line of text to introduce the ceremony, after which he guides the lay people in declaring that they take their refuge in the three refuges or triple gem.

[47]He then continues with reciting the five precepts:

[48][49] "I undertake the training-precept to abstain from onslaught on breathing beings." (

Pali: Pāṇātipātā veramaṇī sikkhāpadaṃ samādiyāmi.)

"I undertake the training-precept to abstain from taking what is not given." (

Pali: Adinnādānā veramaṇī sikkhāpadaṃ samādiyāmi.)

"I undertake the training-precept to abstain from misconduct concerning sense-pleasures." (

Pali: Kāmesumicchācāra veramaṇī sikkhāpadaṃ samādiyāmi.)

"I undertake the training-precept to abstain from false speech." (

Pali: Musāvādā veramaṇī sikkhāpadaṃ samādiyāmi.)

"I undertake the training-precept to abstain from alcoholic drink or drugs that are an opportunity for heedlessness." (

Pali: Surāmerayamajjapamādaṭṭhānā veramaṇī sikkhāpadaṃ samādiyāmi.)

After the lay people have repeated the five precepts after the monk, the monk will close the ceremony reciting:

"These five precepts lead with good behavior to bliss, with good behavior to wealth and success, they lead with good behavior to happiness, therefore purify behavior." (Imāni pañca sikkhāpadāni. Sīlena sugatiṃ yanti, sīlena bhogasampadā, sīlena nibbutiṃ yanti, tasmā sīlaṃ visodhaye.)

[50] In other textual traditions[

edit]

The format of the ceremony for taking the precepts occurs several times in the

Chinese Buddhist Canon.

See also:

Buddhist initiation ritualThe format of the ceremony for taking the precepts occurs several times in the

Chinese Buddhist Canon, in slightly different forms.

[51]One formula of the precepts can be found in the Treatise on Taking Refuge and the Precepts (

simplified Chinese: 归戒要集;

traditional Chinese: 歸戒要集;

pinyin: Guījiè Yāojí):

As all Buddhas refrained from killing until the end of their lives, so I too will refrain from killing until the end of my life.

As all Buddhas refrained from stealing until the end of their lives, so I too will refrain from stealing until the end of my life.

As all Buddhas refrained from sexual misconduct until the end of their lives, so I too will refrain from sexual misconduct until the end of my life.

As all Buddhas refrained from false speech until the end of their lives, so I too will refrain from false speech until the end of my life.

As all Buddhas refrained from alcohol until the end of their lives, so I too will refrain from alcohol until the end of my life.

[52] Similarly, in the

Mūla-Sarvāstivāda texts used in Tibetan Buddhism, the precepts are formulated such that one takes the precepts upon oneself for one's entire lifespan, following the examples of the enlightened disciples of the Buddha (

arahant).

[48] Principles[

edit]

Precept

Accompanying virtues

[12][25]hideRelated to human rights

[53][54] 1. Abstention from killing

living beings Kindness and

compassion Right to life 2. Abstention from theft

Generosity and

renunciation Right of property

3. Abstention from sexual misconduct

Contentment and respect for faithfulness

Right to fidelity in marriage

4. Abstention from falsehood

Being honest and dependable

Right of human dignity

5. Abstention from intoxication

Mindfulness and responsibility

Right of security and safety

Living a life in violation of the precepts is believed to lead to rebirth in a hell.

The five precepts can be found in many places in the Early Buddhist Texts.

[55] The precepts are regarded as means to building good character, or as an expression of such character. The Pāli Canon describes them as means to avoid harm to oneself and others.

[56] It further describes them as gifts toward oneself and others.

[57] Moreover, the texts say that people who uphold them will be confident in any gathering of people,

[15][58] will have wealth and a good reputation, and will die a peaceful death, reborn in heaven

[48][58] or as a

human being. On the other hand, living a life in violation of the precepts is believed to lead to rebirth in an

unhappy destination.

[15] They are understood as principles that define a person as human in body and mind.

[59]The precepts are normative rules, but are formulated and understood as "undertakings"

[60] rather than commandments enforced by a moral authority,

[61][62] according to the voluntary and

gradualist standards of Buddhist ethics.

[63] They are forms of restraint formulated in negative terms, but are also accompanied by virtues and positive behaviors,

[12][13][25] which are cultivated through the practice of the precepts.

[16][note 4] The most important of these virtues is

non-harming (

Pāli and

Sanskrit: ahiṃsa),

[37][65] which underlies all of the five precepts.

[25][note 5] Precisely, the texts say that one should keep the precepts, adhering to the principle of comparing oneself with others:

[67]"For a state that is not pleasant or delightful to me must be so to him also; and a state that is not pleasing or delightful to me, how could I inflict that upon another?"

[68]In other words, all living beings are alike in that they want to be happy and not suffer. Comparing oneself with others, one should therefore not hurt others as one would not want to be hurt.

[69] Ethicist Pinit Ratanakul argues that the compassion which motivates upholding the precepts comes from an understanding that all living beings are equal and of a nature that they are '

not-self' (

Pali: anattā).

[70] Another aspect that is fundamental to this is the belief in karmic retribution.

[71]

A layperson who upholds the precepts is described in the texts as a "jewel among laymen".

In the upholding or violation of the precepts,

intention is crucial.

[72][73] In the Pāli scriptures, an example is mentioned of a person stealing an animal only to

set it free, which was not seen as an

offense of theft.

[72] In the Pāli

commentaries, a precept is understood to be violated when the person violating it finds the object of the transgression (e.g. things to be stolen), is aware of the violation, has the intention to violate it, does actually act on that intention, and does so successfully.

[74]Upholding the precepts is sometimes distinguished in three levels: to uphold them without having formally undertaken them; to uphold them formally, willing to sacrifice one's own life for it; and finally, to spontaneously uphold them.

[75] The latter refers to the arahant, who is understood to be morally incapable of violating the first four precepts.

[76] A layperson who upholds the precepts is described in the texts as a "jewel among laymen".

[77] On the other hand, the most serious violations of the precepts are the

five actions of immediate retribution, which are believed to lead the perpetrator to an unavoidable rebirth in

hell. These consist of injuring a Buddha, killing an arahant, killing one's father or mother, and causing the monastic community to have a schism.

[25] Practice in general[

edit]

Lay followers often undertake these training rules in the same ceremony as they

take the refuges.

[4][78] Monks administer the precepts to the laypeople, which creates an additional psychological effect.

[79] Buddhist lay people may recite the precepts regularly at home, and before an important ceremony at the temple to prepare the mind for the ceremony.

[5][79] Thich Nhat Hanh

Thich Nhat Hanh has written about the five precepts in a wider scope, with regard to social and institutional relations.

The five precepts are at the core of Buddhist morality.

[49] In field studies in some countries like Sri Lanka, villagers describe them as the core of the religion.

[79] Anthropologist

Barend Terwiel found in his fieldwork that most Thai villagers knew the precepts by heart, and many, especially the elderly, could explain the implications of the precepts following traditional interpretations.

[80]Nevertheless, Buddhists do not all follow them with the same strictness.

[49] Devotees who have just started keeping the precepts will typically have to exercise considerable restraint. When they become used to the precepts, they start to embody them more naturally.

[81] Researchers doing field studies in traditional Buddhist societies have found that the five precepts are generally considered demanding and challenging.

[79][82] For example, anthropologist

Stanley Tambiah found in his field studies that strict observance of the precepts had "little positive interest for the villager ... not because he devalues them but because they are not normally open to him". Observing precepts was seen to be mostly the role of a monk or an elderly lay person.

[83] More recently, in a 1997 survey in Thailand, only 13.8% of the respondents indicated they adhered to the five precepts in their daily lives, with the fourth and fifth precept least likely to be adhered to.

[84] Yet, people do consider the precepts worth striving for, and do uphold them out of fear of bad karma and being reborn in

hell, or because they believe in that the Buddha issued these rules, and that they therefore should be maintained.

[85][86] Anthropologist

Melford Spiro found that Burmese Buddhists mostly upheld the precepts to avoid bad karma, as opposed to expecting to gain good karma.

[87] Scholar of religion Winston King observed from his field studies that the moral principles of Burmese Buddhists were based on personal self-developmental motives rather than other-regarding motives. Scholar of religion Richard Jones concludes that the moral motives of Buddhists in adhering to the precepts are based on the idea that renouncing self-service, ironically, serves oneself.

[88]In East Asian Buddhism, the precepts are intrinsically connected with the initiation as a Buddhist lay person. Early Chinese translations such as the Upāsaka-śila Sūtra hold that the precepts should only be ritually transmitted by a monastic. The texts describe that in the ritual the power of the Buddhas and bodhisattvas is transmitted, and helps the initiate to keep the precepts. This "lay ordination" ritual usually occurs after a stay in a temple, and often after a

monastic ordination (Pali: upsampadā); has taken place. The ordained lay person is then given a

religious name. The restrictions that apply are similar to a monastic ordination, such as permission from parents.

[89]In the Theravāda tradition, the precepts are usually taken "each separately" (Pali: visuṃ visuṃ), to indicate that if one precept should be broken, the other precepts are still intact. In very solemn occasions, or for very pious devotees, the precepts may be taken as a group rather than each separately.

[90][91] This does not mean, however, that only some of the precepts can be undertaken; they are always committed to as a complete set.

[92] In East Asian Buddhism, however, the vow of taking the precepts is considered a solemn matter, and it is not uncommon for lay people to undertake only the precepts that they are confident they can keep.

[36] The act of taking a vow to keep the precepts is what makes it karmically effective: Spiro found that someone who did not violate the precepts, but did not have any intention to keep them either, was not believed to accrue any religious merit. On the other hand, when people took a vow to keep the precepts, and then broke them afterwards, the negative karma was considered larger than in the case no vow was taken to keep the precepts.

[93]Several modern teachers such as

Thich Nhat Hanh and

Sulak Sivaraksa have written about the five precepts in a wider scope, with regard to social and institutional relations. In these perspectives, mass production of weapons or spreading untruth through media and education also violates the precepts.

[94][95] On a similar note, human rights organizations in Southeast Asia have attempted to advocate respect for human rights by referring to the five precepts as guiding principles.

[96] First precept[

edit]

Textual analysis[

edit]

The first of the five precepts includes abstention from killing small animals such as insects.

The first precept prohibits the taking of life of a

sentient being. It is violated when someone intentionally and successfully kills such a sentient being, having understood it to be sentient and using effort in the process.

[74][97] Causing injury goes against the spirit of the precept, but does, technically speaking, not violate it.

[98] The first precept includes taking the lives of animals, even small insects. However, it has also been pointed out that the seriousness of taking life depends on the size, intelligence, benefits done and the spiritual attainments of that living being. Killing a large animal is worse than killing a small animal (also because it costs more effort); killing a spiritually accomplished master is regarded as more severe than the killing of another "more average" human being; and killing a human being is more severe than the killing of an animal. But all killing is condemned.

[74][99][100] Virtues that accompany this precept are respect for dignity of life,

[65] kindness and

compassion,

[25] the latter expressed as "trembling for the welfare of others".

[101] A positive behavior that goes together with this precept is protecting living beings.

[13] Positive virtues like sympathy and respect for other living beings in this regard are based on a belief in the

cycle of rebirth—that all living beings must be born and reborn.

[102] The concept of the fundamental

Buddha nature of all human beings also underlies the first precept.

[103]The description of the first precept can be interpreted as a prohibition of capital punishment.

[8] Suicide is also seen as part of the prohibition.

[104] Moreover, abortion (of a sentient being) goes against the precept, since in an act of abortion, the criteria for violation are all met.

[97][105] In Buddhism, human life is understood to start at conception.

[106] A prohibition of abortion is mentioned explicitly in the monastic precepts, and several Buddhist tales warn of the harmful

karmic consequences of abortion.

[107][108] Bioethicist

Damien Keown argues that Early Buddhist Texts do not allow for exceptions with regard to abortion, as they consist of a "consistent' (i.e. exceptionless) pro-life position".

[109][10] Keown further proposes that a middle way approach to the five precepts is logically hard to defend.

[110] Asian studies scholar Giulo Agostini argues, however, that Buddhist commentators in India from the 4th century onward thought abortion did not break the precepts under certain circumstances.

[111]

Buddhist tales describe the

karmic consequences of abortion.

[108]Ordering another person to kill is also included in this precept,

[11][98] therefore requesting or administering euthanasia can be considered a violation of the precept,

[11] as well as advising another person to commit abortion.

[112] With regard to

euthanasia and

assisted suicide, Keown quotes the Pāli

Dīgha Nikāya that says a person upholding the first precept "does not kill a living being, does not cause a living being to be killed, does not approve of the killing of a living being".

[113] Keown argues that in Buddhist ethics, regardless of motives, death can never be the aim of one's actions.

[114]Interpretations of how Buddhist texts regard warfare are varied, but in general Buddhist doctrine is considered to oppose all warfare. In many Jātaka tales, such as that of

Prince Temiya, as well as some historical documents, the virtue of non-violence is taken as an opposition to all war, both offensive and defensive. At the same time, though, the Buddha is often shown not to explicitly oppose war in his conversations with political figures. Buddhologist

André Bareau points out that the Buddha was reserved in his involvement of the details of administrative policy, and concentrated on the moral and spiritual development of his disciples instead. He may have believed such involvement to be futile, or detrimental to Buddhism. Nevertheless, at least one disciple of the Buddha is mentioned in the texts who refrained from retaliating his enemies because of the Buddha, that is King

Pasenadi (Sanskrit: Prasenajit). The texts are ambiguous in explaining his motives though.

[115] In some later Mahāyāna texts, such as in the writings of

Asaṅga, examples are mentioned of people who kill those who persecute Buddhists.

[116][117] In these examples, killing is justified by the authors because protecting Buddhism was seen as more important than keeping the precepts. Another example that is often cited is that of King

Duṭṭhagāmaṇī, who is mentioned in the post-canonical Pāli

Mahāvaṃsa chronicle. In the chronicle, the king is saddened with the loss of life after a war, but comforted by a Buddhist monk, who states that nearly everyone who was killed did not uphold the precepts anyway.

[118][119] Buddhist studies scholar

Lambert Schmithausen argues that in many of these cases Buddhist teachings like that of

emptiness were misused to further an agenda of war or other violence.

[120] In practice[

edit]

See also:

Religion and capital punishment § Buddhism, and

Abortion in Japan

In Buddhism, there are different opinions about whether vegetarianism should be practiced.

[25]Field studies in Cambodia and Burma have shown that many Buddhists considered the first precept the most important, or the most blamable.

[49][98] In some traditional communities, such as in

Kandal Province in pre-war Cambodia, as well as Burma in the 1980s, it was uncommon for Buddhists to slaughter animals, to the extent that meat had to be bought from non-Buddhists.

[49][66] In his field studies in Thailand in the 1960s, Terwiel found that villagers did tend to kill insects, but were reluctant and self-conflicted with regard to killing larger animals.

[121] In Spiro's field studies, however, Burmese villagers were highly reluctant even to kill insects.

[66]Early Buddhists did not adopt a

vegetarian lifestyle. Indeed, in several Pāli

texts vegetarianism is described as irrelevant in the spiritual purification of the mind. There are prohibitions on certain types of meat, however, especially those which are condemned by society. The idea of abstaining from killing animal life has also led to a prohibition on professions that involve trade in flesh or living beings, but not to a full prohibition of all agriculture that involves cattle.

[122] In modern times, referring to the

law of supply and demand or other principles, some Theravādin Buddhists have attempted to promote vegetarianism as part of the five precepts. For example, the Thai

Santi Asoke movement practices vegetarianism.

[62][123]Furthermore, among some schools of Buddhism, there has been some debate with regard to a principle in the monastic discipline. This principle states that a Buddhist monk cannot accept meat if it comes from animals especially slaughtered for him. Some teachers have interpreted this to mean that when the recipient has no knowledge on whether the animal has been killed for him, he cannot accept the food either. Similarly, there has been debate as to whether laypeople should be vegetarian when adhering to the five precepts.

[25] Though vegetarianism among Theravādins is generally uncommon, it has been practiced much in East Asian countries,

[25] as some Mahāyāna texts, such as the

Mahāparanirvana Sūtra and the

Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra, condemn the eating of meat.

[12][124] Nevertheless, even among Mahāyāna Buddhists—and East Asian Buddhists—there is disagreement on whether vegetarianism should be practiced. In the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra, biological, social and hygienic reasons are given for a vegetarian diet; however, historically, a major factor in the development of a vegetarian lifestyle among Mahāyāna communities may have been that Mahāyāna monastics cultivated their own crops for food, rather than living from

alms.

[125] Already from the 4th century CE, Chinese writer

Xi Chao understood the five precepts to include vegetarianism.

[124]

The

Dalai Lama has rejected forms of protest that are self-harming.

[63]Apart from trade in flesh or living beings, there are also other professions considered undesirable. Vietnamese teacher Thich Nhat Hanh gives a list of examples, such as working in the arms industry, the military, police, producing or selling poison or drugs such as alcohol and tobacco.

[126]In general, the first precept has been interpreted by Buddhists as a call for non-violence and pacifism. But there have been some exceptions of people who did not interpret the first precept as an opposition to war. For example, in the twentieth century, some Japanese Zen teachers wrote in support of violence in war, and some of them argued this should be seen as a means to uphold the first precept.

[127] There is some debate and controversy surrounding the problem whether a person can commit suicide, such as

self-immolation, to reduce other people's suffering in the long run, such as in protest to improve a political situation in a country. Teachers like the

Dalai Lama and

Shengyan have rejected forms of protest like self-immolation, as well as other acts of self-harming or fasting as forms of protest.

[63]Although capital punishment goes against the first precept, as of 2001, many countries in Asia still maintained the death penalty, including Sri Lanka, Thailand, China and Taiwan. In some Buddhist countries, such as Sri Lanka and Thailand, capital punishment was applied during some periods, while during other periods no capital punishment was used at all. In other countries with Buddhism, like China and Taiwan, Buddhism, or any religion for that matter, has had no influence in policy decisions of the government. Countries with Buddhism that have abolished capital punishment include Cambodia and Hong Kong.

[128]In general, Buddhist traditions oppose abortion.

[111] In many countries with Buddhist traditions such as Thailand, Taiwan, Korea and Japan, however, abortion is a widespread practice, whether legal or not. Many people in these countries consider abortion immoral, but also think it should be less prohibited. Ethicist Roy W. Perrett, following Ratanakul, argues that this field research data does not so much indicate hypocrisy, but rather points at a "middle way" in applying Buddhist doctrine to solve a

moral dilemma. Buddhists tend to take "both sides" on the pro-life–pro-choice debate, being against the taking of life of a fetus in principle, but also believing in compassion toward mothers. Similar attitudes may explain the Japanese

mizuko kuyō ceremony, a Buddhist memorial service for aborted children, which has led to a debate in Japanese society concerning abortion, and finally brought the Japanese to a consensus that abortion should not be taken lightly, though it should be legalized. This position, held by Japanese Buddhists, takes the middle ground between the Japanese

neo-Shinto "pro-life" position, and the

liberationist, "pro-choice" arguments.

[129] Keown points out, however, that this compromise does not mean a Buddhist

middle way between two extremes, but rather incorporates two opposite perspectives.

[110] In Thailand, women who wish to have abortion usually do so in the early stages of pregnancy, because they believe the karmic consequences are less then. Having had abortion, Thai women usually make merits to compensate for the negative karma.

[130] Second precept[

edit]

Textual analysis[

edit]

Studies discovered that people who did not adhere to the five precepts more often tended to pay bribes.

The second precept prohibits theft, and involves the intention to steal what one perceives as not belonging to oneself ("what is not given") and acting successfully upon that intention. The severity of the act of theft is judged by the worth of the owner and the worth of that which is stolen. Underhand dealings, fraud, cheating and forgery are also included in this precept.

[74][131] Accompanying virtues are

generosity,

renunciation,

[12][25] and

right livelihood,

[132] and a positive behavior is the protection of other people's property.

[13] In practice[

edit]

The second precept includes different ways of stealing and fraud. Borrowing without permission is sometimes included,

[62][80] as well as gambling.

[80][133] Psychologist Vanchai Ariyabuddhiphongs did studies in the 2000s and 2010s in Thailand and discovered that people who did not adhere to the five precepts more often tended to believe that money was the most important goal in life, and would more often pay bribes than people who did adhere to the precepts.

[134][135] On the other hand, people who observed the five precepts regarded themselves as wealthier and happier than people who did not observe the precepts.

[136]Professions that are seen to violate the second precept include working in the gambling industry or marketing products that are not actually required for the customer.

[137] Third precept[

edit]

Textual analysis[

edit]

The third precept condemns sexual misconduct. This has been interpreted in classical texts to include adultery with a married or engaged person, fornication, rape, incest, sex with a minor (or a person "protected by any relative"), and sex with a prostitute.

[138] In later texts, details such as intercourse at an inappropriate time or inappropriate place are also counted as breaches of the third precept.

[139] Masturbation goes against the spirit of the precept, though in the early texts it is not prohibited for laypeople.

[140][141]The third precept is explained as leading to greed in oneself and harm to others. The transgression is regarded as more severe if the other person is a good person.

[140][141] Virtues that go hand-in-hand with the third precept are contentment, especially with one's partner,

[25][101] and recognition and respect for faithfulness in a marriage.

[13] In practice[

edit]

The third precept is interpreted as avoiding harm to another by using sensuality in the wrong way. This means not engaging with inappropriate partners, but also respecting one's personal commitment to a relationship.

[62] In some traditions, the precept also condemns adultery with a person whose spouse agrees with the act, since the nature of the act itself is condemned. Furthermore, flirting with a married person may also be regarded as a violation.

[80][138] Though prostitution is discouraged in the third precept, it is usually not actively prohibited by Buddhist teachers.

[142] With regard to applications of the principles of the third precept, the precept, or any Buddhist principle for that matter, is usually not connected with a stance against contraception.

[143][144] In traditional Buddhist societies such as Sri Lanka, pre-marital sex is considered to violate the precept, though this is not always adhered to by people who already intend to marry.

[141][145]In the interpretation of modern teachers, the precept includes any person in a sexual relationship with another person, as they define the precept by terms such as sexual responsibility and long-term commitment.

[138] Some modern teachers include masturbation as a violation of the precept,

[146] others include certain professions, such as those that involve sexual exploitation, prostitution or pornography, and professions that promote unhealthy sexual behavior, such as in the entertainment industry.

[137] Fourth precept[

edit]

Textual analysis[

edit]

Work that involves online scams can also be included as a violation of the fourth precept.

The fourth precept involves falsehood spoken or committed to by action.

[140] Avoiding other forms of wrong speech are also considered part of this precept, consisting of malicious speech, harsh speech and gossip.

[147][148] A breach of the precept is considered more serious if the falsehood is motivated by an ulterior motive

[140] (rather than, for example, "a small white lie").

[149] The accompanying virtue is

being honest and dependable,

[25][101] and involves honesty in work, truthfulness to others, loyalty to superiors and gratitude to benefactors.

[132] In Buddhist texts, this precept is considered second in importance to the first precept, because a lying person is regarded to have no shame, and therefore capable of many wrongs.

[146] Untruthfulness is not only to be avoided because it harms others, but also because it goes against the Buddhist ideal of finding the

truth.

[149][150] In practice[

edit]

The fourth precept includes avoidance of lying and harmful speech.

[151] Some modern teachers such as Thich Nhat Hanh interpret this to include avoiding spreading false news and uncertain information.

[146] Work that involves data manipulation, false advertising or online scams can also be regarded as violations.

[137] Terwiel reports that among Thai Buddhists, the fourth precept is also seen to be broken when people insinuate, exaggerate or speak abusively or deceitfully.

[80] Fifth precept[

edit]

Textual analysis[

edit]

The fifth precept prohibits intoxication through alcohol, drugs or other means.

[12]The fifth precept prohibits intoxication through alcohol, drugs or other means, and its virtues are

mindfulness and responsibility,

[12][13] applied to

food, work, behavior, and with regard to the

nature of life.

[132] Awareness, meditation and

heedfulness can also be included here.

[125] Medieval Pāli commentator

Buddhaghosa writes that whereas violating the first four precepts may be more or less blamable depending on the person or animal affected, the fifth precept is always "greatly blamable", as it hinders one from understanding the Buddha's teaching and may lead one to "madness".

[18] In ancient China, Daoshi described alcohol as the "doorway to laxity and idleness" and as a cause of suffering. Nevertheless, he did describe certain cases when drinking was considered less of a problem, such as in the case of a queen distracting the king by alcohol to prevent him from murder. However, Daoshi was generally strict in his interpretations: for example, he allowed medicinal use of alcohol only in extreme cases.

[152] Early Chinese translations of the

Tripitaka describe negative consequences for people breaking the fifth precept, for themselves and their families. The Chinese translation of the Upāsikaśila Sūtra, as well as the Pāli version of the

Sigālovāda Sutta, speak of ill consequences such as loss of wealth, ill health, a bad reputation and "stupidity", concluding in a rebirth in hell.

[18][153] The

Dīrghāgama adds to that that alcohol leads to quarreling, negative states of mind and damage to one's intelligence. The Mahāyāna

Brahmajāla Sūtra[note 6] describes the dangers of alcohol in very strong terms, including the selling of alcohol.

[154] Similar arguments against alcohol can be found in

Nāgārjuna's writings.

[155] The strict interpretation of prohibition of alcohol consumption can be supported by the Upāli Sūtra's statement that a disciple of the Buddha should not drink any alcohol, "even a drop on the point of a blade of grass". However, in the writing of some

Abhidharma commentators, consumption was condemned or condoned, depending on the intention with which alcohol was consumed.

[156] In practice[

edit]

The fifth precept is regarded as important, because drinking alcohol is condemned for the sluggishness and lack of self-control it leads to,

[72][157] which might lead to breaking the other precepts.

[18] In Spiro's field studies, violating the fifth precept was seen as the worst of all the five precepts by half of the monks interviewed, citing the harmful consequences.

[18] Nevertheless, in practice it is often disregarded by lay people.

[158] In Thailand, drinking alcohol is fairly common, even drunkenness.

[159] Among Tibetans, drinking beer is common, though this is only slightly alcoholic.

[155] Medicinal use of alcohol is generally not frowned upon,

[145] and in some countries like Thailand and Laos, smoking is usually not regarded as a violation of the precept. Thai and Laotian monks have been known to smoke, though monks who have received more training are less likely to smoke.

[43][160] On a similar note, as of 2000, no Buddhist country prohibited the sale or consumption of alcohol, though in Sri Lanka Buddhist revivalists unsuccessfully attempted to get a full prohibition passed in 1956.

[43] Moreover, pre-Communist Tibet used to prohibit smoking in some areas of the capital. Monks were prohibited from smoking, and the import of tobacco was banned.

[43]Thich Nhat Hanh also includes mindful consumption in this precept, which consists of unhealthy food, unhealthy entertainment and unhealthy conversations, among others.

[137][161] Present trends[

edit]

Some scholars have proposed that the five precepts be introduced as a component in mindfulness training programs.

In modern times, adherence to the precepts among Buddhists is less strict than it traditionally was. This is especially true for the third precept. For example, in Cambodia in the 1990s and 2000s, standards with regard to sexual restraint were greatly relaxed.

[162] Some Buddhist movements and communities have tried to go against the modern trend of less strict adherence to the precepts. In Cambodia, a

millenarian movement led by

Chan Yipon promoted the revival of the five precepts.

[162] And in the 2010s, the

Supreme Sangha Council in Thailand ran a nationwide program called "

The Villages Practicing the Five Precepts", aiming to encourage keeping the precepts, with an extensive classification and reward system.

[163][164]In many Western Buddhist organizations, the five precepts play a major role in developing ethical guidelines.

[165] Furthermore, Buddhist teachers such as

Philip Kapleau, Thich Nhat Hanh and

Robert Aitken have promoted mindful consumption in the West, based on the five precepts.

[161] In another development in the West, some scholars working in the field of

mindfulness training have proposed that the five precepts be introduced as a component in such trainings. Specifically, to prevent organizations from using mindfulness training to further an economical agenda with harmful results to its employees, the economy or the environment, the precepts could be used as a standardized ethical framework. As of 2015, several training programs made explicit use of the five precepts as secular, ethical guidelines. However, many mindfulness training specialists consider it problematic to teach the five precepts as part of training programs in secular contexts because of their religious origins and import.

[166]Peace studies scholar Theresa Der-lan Yeh notes that the five precepts address physical, economical, familial and verbal aspects of interaction, and remarks that many conflict prevention programs in schools and communities have integrated the five precepts in their curriculum. On a similar note, peace studies founder

Johan Galtung describes the five precepts as the "basic contribution of Buddhism in the creation of peace".

[167] Theory of ethics[

edit]

Peace studies

Peace studies founder

Johan Galtung describes the five precepts as the "basic contribution of Buddhism in the creation of peace".

[167]Studying lay and monastic ethical practice in traditional Buddhist societies, Spiro argued ethical guidelines such as the five precepts are adhered to as a means to a higher end, that is, a better rebirth or enlightenment. He therefore concluded that Buddhist ethical principles like the five precepts are similar to Western

utilitarianism.

[63] Keown, however, has argued that the five precepts are regarded as rules that cannot be violated, and therefore may indicate a

deontological perspective in Buddhist ethics.

[168][169] On the other hand, Keown has also suggested that Aristotle's

virtue ethics could apply to Buddhist ethics, since the precepts are considered good in themselves, and mutually dependent on other aspects of the Buddhist path of practice.

[63][170] Philosopher Christopher Gowans disagrees that Buddhist ethics are deontological, arguing that virtue and consequences are also important in Buddhist ethics. Gowans argues that there is no moral theory in Buddhist ethics that covers all conceivable situations such as when two precepts may be in conflict, but is rather characterized by "a commitment to and nontheoretical grasp of the basic Buddhist moral values".

[171] As of 2017, many scholars of Buddhism no longer think it is useful to try to fit Buddhist ethics into a Western philosophical category.

[172] Comparison with human rights[

edit]

Keown has argued that the five precepts are very similar to human rights, with regard to subject matter and with regard to their universal nature.

[173] Other scholars, as well as Buddhist writers and human rights advocates, have drawn similar comparisons.

[54][174] For example, the following comparisons are drawn:

Keown compares the first precept with the

right to life.

[53] The Buddhism-informed Cambodian Institute for Human Rights (CIHR) draws the same comparison.

[175] The second precept is compared by Keown and the CIHR with the right of property.

[53][175] The third precept is compared by Keown to the "right to fidelity in marriage";

[53] the CIHR construes this broadly as "right of individuals and the rights of society".

[176] The fourth precept is compared by Keown with the "right not to be lied to";

[53] the CIHR writes "the right of human dignity".

[176] Finally, the fifth precept is compared by the CIHR with the right of individual security and a safe society.

[176] Keown describes the relationship between Buddhist precepts and human rights as "look[ing] both ways along the juridical relationship, both to what one is due to do, and to what is due to one".

[176][177] On a similar note, Cambodian human rights advocates have argued that for human rights to be fully implemented in society, the strengthening of individual morality must also be addressed.

[176] Buddhist monk and scholar

Phra Payutto sees the

Human Rights Declaration as an unfolding and detailing of the principles that are found in the five precepts, in which a sense of ownership is given to the individual, to make legitimate claims on one's rights. He believes that human rights should be seen as a part of human development, in which one develops from

moral discipline (Pali: sīla), to

concentration (Pali: samādhi) and finally

wisdom (Pali: paññā). He does not believe, however, that human rights are

natural rights, but rather human conventions. Buddhism scholar Somparn Promta disagrees with him. He argues that human beings do have natural rights from a Buddhist perspective, and refers to the attūpanāyika-dhamma, a teaching in which the Buddha prescribes a kind of

golden rule of comparing oneself with others. (See

§Principles, above.) From this discourse, Promta concludes that the Buddha has laid down the five precepts in order to protect individual rights such as right of life and property: human rights are implicit within the five precepts. Academic Buntham Phunsap argues, however, that though human rights are useful in culturally pluralistic societies, they are in fact not required when society is entirely based on the five precepts. Phunsap therefore does not see human rights as part of Buddhist doctrine.

[178] See also[

edit]

Dhammika Sutta Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, five principles applied in geopolitics, for which the same term is used

Five Virtues (in Sikhism)

Notes[

edit]

^ Also spelled as pañcasīlani and pañcasikkhāpadani, respectively.

[1] ^ The fifth precept has also been connected with

right mindfulness.

[18] ^ The 6th century CE

Chāndogya Upaniśad contains four principles identical to the Buddhist precepts, but lying is not mentioned.

[35] In contemporary

Jainism, the fifth principle became "appropriation of any sort".

[30] ^ This dual meaning in negative formulations is typical for an Indic language like

Sanskrit.

[64] ^ However, anthropologist

Melford Spiro argued that the fundamental virtue behind the precepts was

loving-kindness, not "the Hindu notion of non-violence".

[66] ^ Not to be confused with the early Buddhist

Brahmajala Sutta.

Citations[

edit]

^

Jump up to:a b c d e Terwiel 2012, p. 178.

^ Kent 2008, p. 127 n.17.

^ Gombrich 1995, p. 77.

^

Jump up to:a b c d e f g Getz 2004, p. 673.

^

Jump up to:a b Terwiel 2012, pp. 178–79.

^

Jump up to:a b Keown 2013b, p. 638.

^

Jump up to:a b Wai 2002, p. 4.

^

Jump up to:a b Alarid & Wang 2001, pp. 236–37.

^ Keown 2016a, p. 213.

^

Jump up to:a b Perrett 2000, p. 110.

^

Jump up to:a b c Keown 2016b, p. 170.

^

Jump up to:a b c d e f g Gwynne 2017, The Buddhist Pancasila.

^

Jump up to:a b c d e f Wijayaratna 1990, pp. 166–67.

^ Gowans 2013, p. 440.

^

Jump up to:a b c d Goodman, Charles (2017).

Ethics in Indian and Tibetan Buddhism. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab,

Stanford University.

Archived from the original on 8 July 2010.

^

Jump up to:a b Edelglass 2013, p. 479.

^ Powers 2013, āryāṣtāṅga-mārga.

^

Jump up to:a b c d e Harvey 2000, p. 77.

^ Osto 2015.

^ McFarlane 1997.

^ Wijayaratna 1990, pp. 166–57.

^ De Silva 2016, p. 79.

^ Keown 2012, p. 31.

^ Tambiah 1992, p. 121.

^

Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m Cozort 2015.

^ Cozort & Shields 2018, Dōgen, The Bodhisattva Path according to the Ugra.

^

Jump up to:a b Funayama 2004, p. 98.

^ Funayama 2004, p. 105.

^ Keown 2005, Precepts.

^

Jump up to:a b c d Kohn 1994, p. 173.

^ Keown 2003, p. 210.

^ Cozort & Shields 2018, Precepts in Early and Theravāda Buddhism.

^

Jump up to:a b Gombrich 2006, p. 78.

^ Kohn 1994, pp. 171, 173.

^ Tachibana 1992, p. 58.

^

Jump up to:a b Harvey 2000, p. 83.

^

Jump up to:a b "Ahiṃsā". The Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Religions.

Oxford University Press. 1997.

Archived from the original on 24 August 2018 – via Encyclopedia.com.

^

Jump up to:a b Mcdermott 1989, p. 273.

^ Kohn 1994, pp. 173–74.

^ Terwiel 2012, pp. 178–79, 205.

^ Kohn 1994, pp. 171, 175–76.

^ Benn 2005, pp. 214, 223–24, 226, 230–31.

^

Jump up to:a b c d Harvey 2000, p. 79.

^ Benn 2005, p. 231.

^ Kohn 1994, pp. 176–78, 184–85.

^ Terwiel 2012, pp. 179–80.

^ Terwiel 2012, p. 181.

^

Jump up to:a b c Harvey 2000, p. 67.

^

Jump up to:a b c d e Ledgerwood 2008, p. 152.

^ Terwiel 2012, p. 182.

^ "CBETA T18 No. 916". Cbeta.org. Archived from

the original on 31 July 2012.

"CBETA T24 No. 1488". Cbeta.org. 30 August 2008. Archived from

the original on 31 July 2012.Shih, Heng-ching (1994).

The Sutra on Upāsaka Precepts (PDF). Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research.

ISBN 978-0-9625618-5-6.

"CBETA 電子佛典集成 卍續藏 (X) 第 60 冊 No.1129". Cbeta.org. 30 August 2008. Archived from

the original on 31 July 2012.

^ "X60n1129_002 歸戒要集 第2卷". CBETA 電子佛典集成. Cbeta.org.

Archived from the original on 24 August 2018.

^

Jump up to:a b c d e Keown 2012, p. 33.

^

Jump up to:a b Ledgerwood & Un 2010, pp. 540–41.

^ Tedesco 2004, p. 91.

^ MacKenzie 2017, p. 2.

^ Harvey 2000, p. 66.

^

Jump up to:a b Tachibana 1992, p. 63.

^ Wai 2002, p. 2.

^ Gombrich 2006, p. 66.

^ Keown 2003, p. 268.

^

Jump up to:a b c d Meadow 2006, p. 88.

^

Jump up to:a b c d e Buswell 2004.

^ Keown 1998, pp. 399–400.

^

Jump up to:a b Keown 2013a, p. 616.

^

Jump up to:a b c Spiro 1982, p. 45.

^ Harvey 2000, pp. 33, 71.

^ Harvey 2000, p. 33.

^ Harvey 2000, p. 120.

^ Ratanakul 2007, p. 241.

^ Horigan 1996, p. 276.

^

Jump up to:a b c Mcdermott 1989, p. 275.

^ Keown 1998, p. 386.

^

Jump up to:a b c d Leaman 2000, p. 139.

^ Leaman 2000, p. 141.

^ Keown 2003, p. 1.

^ De Silva 2016, p. 63.

^ "Festivals and Calendrical Rituals". Encyclopedia of Buddhism.

The Gale Group. 2004.

Archived from the original on 23 December 2017 – via Encyclopedia.com.

^

Jump up to:a b c d Harvey 2000, p. 80.

^

Jump up to:a b c d e Terwiel 2012, p. 183.

^ MacKenzie 2017, p. 10.

^ Gombrich 1995, p. 286.

^ Keown 2017, p. 28.

^ Ariyabuddhiphongs 2009, p. 193.

^ Terwiel 2012, p. 188.

^ Spiro 1982, p. 449.

^ Spiro 1982, pp. 99, 102.

^ Jones 1979, p. 374.

^ Harvey 2000, pp. 80–81.

^ Harvey 2000, p. 82.

^ Terwiel 2012, p. 180.

^ Harvey 2000, pp. 82–83.

^ Spiro 1982, p. 217.

^ Queen 2013, p. 532.

^ "Engaged Buddhism". Encyclopedia of Religion.

Thomson Gale. 2005.

Archived from the original on 29 April 2017 – via Encyclopedia.com.

^ Ledgerwood 2008, p. 154.

^

Jump up to:a b "Religions - Buddhism: Abortion".

BBC.

Archived from the original on 24 August 2018.

^

Jump up to:a b c Harvey 2000, p. 69.

^ Mcdermott 1989, pp. 271–72.

^ Harvey 2000, p. 156.

^

Jump up to:a b c Harvey 2000, p. 68.

^ Wai 2002, p. 293.

^ Horigan 1996, p. 275.

^ Wai 2002, p. 11.

^ Harvey 2000, pp. 313–14.

^ Keown 2016a, p. 206.

^ Mcdermott 2016, pp. 157–64.

^

Jump up to:a b Perrett 2000, p. 101.

^ Keown 2016a, p. 209.

^

Jump up to:a b Keown 2016a, p. 205.

^

Jump up to:a b Agostini 2004, pp. 77–78.

^ Harvey 2000, p. 314.

^ Keown 1998, p. 400.

^ Keown 1998, p. 402.

^ Schmithausen 1999, pp. 50–52.

^ Schmithausen 1999, pp. 57–59.

^ Jones 1979, p. 380.

^ Jones 1979, pp. 380, 385 n.2.

^ Schmithausen 1999, pp. 56–57.

^ Schmithausen 1999, pp. 60–62.

^ Terwiel 2012, p. 186.

^ Mcdermott 1989, pp. 273–74, 276.

^ Swearer 2010, p. 177.

^

Jump up to:a b Kieschnick 2005, p. 196.

^

Jump up to:a b Gwynne 2017, Ahiṃsa and Samādhi.

^ Johansen & Gopalakrishna 2016, p. 341.

^ "Religions - Buddhism: War".

BBC.

Archived from the original on 24 August 2018.

^ Alarid & Wang 2001, pp. 239–41, 244 n.1.

^ Perrett 2000, pp. 101–03, 109.

^ Ratanakul 1998, p. 57.

^ Harvey 2000, p. 70.

^

Jump up to:a b c Wai 2002, p. 3.

^ Ratanakul 2007, p. 253.

^ Ariyabuddhiphongs & Hongladarom 2011, pp. 338–39.

^ Ariyabuddhiphongs 2007, p. 43.

^ Jaiwong & Ariyabuddhiphongs 2010, p. 337.

^

Jump up to:a b c d Johansen & Gopalakrishna 2016, p. 342.

^

Jump up to:a b c Harvey 2000, pp. 71–72.

^ Harvey 2000, p. 73.

^

Jump up to:a b c d Leaman 2000, p. 140.

^

Jump up to:a b c Harvey 2000, p. 72.

^ Derks 1998.

^ "Eugenics and Religious Law: IV. Hinduism and Buddhism". Encyclopedia of Bioethics.

The Gale Group. 2004.

Archived from the original on 24 August 2018 – via Encyclopedia.com.

^ Perrett 2000, p. 112.

^

Jump up to:a b Gombrich 1995, p. 298.

^

Jump up to:a b c Harvey 2000, p. 74.

^ Segall 2003, p. 169.

^ Harvey 2000, pp. 74, 76.

^

Jump up to:a b Harvey 2000, p. 75.

^ Wai 2002, p. 295.

^ Powers 2013, pañca-śīla.

^ Benn 2005, pp. 224, 227.

^ Benn 2005, p. 225.

^ Benn 2005, pp. 225–26.

^

Jump up to:a b Harvey 2000, p. 78.

^ Harvey 2000, pp. 78–79.

^ Tachibana 1992, p. 62.

^ Neumaier 2006, p. 78.

^ Terwiel 2012, p. 185.

^ Vanphanom et al. 2009, p. 100.

^

Jump up to:a b Kaza 2000, p. 24.

^

Jump up to:a b Ledgerwood 2008, p. 153.

^ สมเด็จวัดปากน้ำชงหมูบ้านรักษาศีล 5 ให้อปท.ชวนประชาชนยึดปฎิบัติ [Wat Paknam's Somdet proposes the Five Precept Village for local administrators to persuade the public to practice].

Khao Sod (in Thai). Matichon Publishing. 15 October 2013. p. 31.

^ 39 ล้านคนร่วมหมู่บ้านศีล 5 สมเด็จพระมหารัชมังคลาจารย์ ย้ำทำต่อเนื่อง [39 million people have joined Villages Practicing Five Precepts, Somdet Phra Maharatchamangalacharn affirms it should be continued].

Thai Rath (in Thai). Wacharapol. 11 March 2017.

Archived from the original on 21 November 2017.

^ Bluck 2006, p. 193.

^ Baer 2015, pp. 957–59, 965–66.

^

Jump up to:a b Yeh 2006, p. 100.

^ Keown 2013a, p. 618.

^ Keown 2013b, p. 643.

^ Edelglass 2013, p. 481.

^ Gowans 2017, pp. 57, 61.

^ Davis 2017, p. 5.

^ Keown 2012, pp. 31–34.

^ Seeger 2010, p. 78.

^

Jump up to:a b Ledgerwood & Un 2010, p. 540.

^

Jump up to:a b c d e Ledgerwood & Un 2010, p. 541.

^ Keown 2012, pp. 20–22, 33.

^ Seeger 2010, pp. 78–80, 85–86, 88.

References[

edit]

Agostini, G. (2004),

"Buddhist Sources on Feticide as Distinct from Homicide", Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, 27 (1): 63–95

Alarid, Leanne Fiftal; Wang, Hsiao-Ming (2001), "Mercy and Punishment: Buddhism and the Death Penalty",

Social Justice, 28 (1 (83)): 231–47,

JSTOR 29768067 Ariyabuddhiphongs, Vanchai (March 2007), "Money Consciousness and the Tendency to Violate the Five Precepts Among Thai Buddhists", International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 17 (1): 37–45,

doi:

10.1080/10508610709336852,

S2CID 143789118 Ariyabuddhiphongs, Vanchai (1 April 2009), "Buddhist Belief in Merit (Punña), Buddhist Religiousness and Life Satisfaction Among Thai Buddhists in Bangkok, Thailand", Archive for the Psychology of Religion, 31 (2): 191–213,

doi:

10.1163/157361209X424457,

S2CID 143972814 Ariyabuddhiphongs, Vanchai; Hongladarom, Chanchira (1 January 2011), "Violation of Buddhist Five Precepts, Money Consciousness, and the Tendency to Pay Bribes among Organizational Employees in Bangkok, Thailand", Archive for the Psychology of Religion, 33 (3): 325–44,

doi:

10.1163/157361211X594168,

S2CID 145596879 Baer, Ruth (21 June 2015), "Ethics, Values, Virtues, and Character Strengths in Mindfulness-Based Interventions: A Psychological Science Perspective",

Mindfulness, 6 (4): 956–69,

doi:

10.1007/s12671-015-0419-2 Benn, James A. (2005),

"Buddhism, Alcohol, and Tea in Medieval China" (PDF), in Sterckx, R. (ed.), Of Tripod and Palate: Food, Politics, and Religion in Traditional China,

Springer Nature, pp. 213–36,

ISBN 978-1-4039-7927-8 Bluck, Robert (2006), British Buddhism: Teachings, Practice and Development,

Taylor & Francis,

CiteSeerX 10.1.1.694.9462,

ISBN 978-0-203-97011-9 Buswell, Robert E., ed. (2004),

"Ethics", Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Macmillan Reference USA,

Thomson Gale,

ISBN 978-0-02-865720-2,

archived from the original on 24 August 2018 – via Encyclopedia.com

Cozort, Daniel (2015),

"Ethics", in Powers, John (ed.), The Buddhist World,

Routledge,

ISBN 978-1-317-42016-3 Cozort, Daniel; Shields, James Mark (2018),

The Oxford Handbook of Buddhist Ethics,

Oxford University Press,

ISBN 978-0-19-106317-6 Davis, J.H. (2017), "Introduction", in Davis, J.H. (ed.), A Mirror is for Reflection: Understanding Buddhist Ethics,

Oxford University Press, pp. 1–13

Derks, Annuska (1998),

Trafficking of Vietnamese women and children to Cambodia(PDF), International Organization for Migration,

archived (PDF) from the original on 6 August 2016

De Silva, Padmasiri (2016),

Environmental Philosophy and Ethics in Buddhism,

Springer Nature,

ISBN 978-1-349-26772-9 Edelglass, William (2013),

"Buddhist Ethics and Western Moral Philosophy" (PDF), in Emmanuel, Steven M. (ed.), A Companion to Buddhist Philosophy (1st ed.),

Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 476–90,

ISBN 978-0-470-65877-2 Funayama, Tōru (2004), "The Acceptance of Buddhist Precepts by the Chinese in the Fifth Century", Journal of Asian History, 38 (2): 97–120,

JSTOR 41933379 Getz, Daniel A. (2004),

"Precepts", in Buswell, Robert E. (ed.), Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Macmillan Reference USA,

Thomson Gale,

ISBN 978-0-02-865720-2,

archived from the original on 23 December 2017, retrieved 13 July 2018

Gombrich, Richard F. (1995),

Buddhist Precept and Practice: Traditional Buddhism in the Rural Highlands of Ceylon,

Kegan Paul, Trench and Company,

ISBN 978-0-7103-0444-5 Gombrich, Richard F. (2006),

Theravāda Buddhism: A Social History from Ancient Benares to Modern Colombo (PDF) (2nd ed.),

Routledge,

ISBN 978-0-203-01603-9, archived from

the original (PDF) on 17 November 2017, retrieved 1 August 2018

Gowans, Christopher W. (2013),

"Ethical Thought in Indian Buddhism" (PDF), in Emmanuel, Steven M. (ed.), A Companion to Buddhist Philosophy,

Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 429–51,

ISBN 978-0-470-65877-2 Gowans, Christopher W. (2017), "Buddhist Moral Thought and Western Moral Philosophy", in Davis, J.H. (ed.), A Mirror is for Reflection: Understanding Buddhist Ethics,

Oxford University Press, pp. 53–72

Gwynne, Paul (2017),

World Religions in Practice: A Comparative Introduction,

John Wiley & Sons,

ISBN 978-1-118-97227-4 Harvey, Peter (2000),

An Introduction to Buddhist Ethics: Foundations, Values and Issues(PDF),

Cambridge University Press,

ISBN 978-0-511-07584-1 Horigan, D.P. (1996),

"Of Compassion and Capital Punishment: A Buddhist Perspective on the Death Penalty", American Journal of Jurisprudence, 41: 271–88,

doi:

10.1093/ajj/41.1.271 Jaiwong, Donnapat; Ariyabuddhiphongs, Vanchai (1 January 2010), "Observance of the Buddhist Five Precepts, Subjective Wealth, and Happiness among Buddhists in Bangkok, Thailand", Archive for the Psychology of Religion, 32 (3): 327–44,

doi:

10.1163/157361210X533274,

S2CID 144557806 Johansen, Barry-Craig P.; Gopalakrishna, D. (21 July 2016), "A Buddhist View of Adult Learning in the Workplace",

Advances in Developing Human Resources, 8 (3): 337–45,

doi:

10.1177/1523422306288426,

S2CID 145131162 Jones, R. H. (1 September 1979), "Theravada Buddhism and Morality",

Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 48 (3): 371–87,

doi:

10.1093/jaarel/48.3.371 Kaza, Stephanie (2000), "Overcoming the Grip of Consumerism", Buddhist-Christian Studies, 20: 23–42,

doi:

10.1353/bcs.2000.0013,

JSTOR 1390317,

S2CID 1625439 Kent, Alexandra (2008),

"The Recovery of the King" (PDF), in Kent, Alexandra; Chandler, David (eds.), People of Virtue: Reconfiguring Religion, Power and Moral Order in Cambodia Today,

Nordic Institute of Asian Studies, pp. 109–27,

ISBN 978-87-7694-036-2,

archived(PDF) from the original on 24 August 2018

Keown, Damien (1998), "Suicide, Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia: A Buddhist Perspective",

Journal of Law and Religion, 13 (2): 385–405,

doi:

10.2307/1051472,

JSTOR 1051472,

PMID 15112691 Keown, Damien (2003),

A Dictionary of Buddhism,

Oxford University Press,

ISBN 978-0-19-157917-2 Keown, Damien (2005),

Buddhist Ethics: A Very Short Introduction,

Oxford University Press,

ISBN 978-0-19-157794-9 Keown, Damien (2012),

"Are There Human Rights in Buddhism?", in Husted, Wayne R.; Keown, Damien; Prebish, Charles S. (eds.), Buddhism and Human Rights,

Routledge, pp. 15–42,

ISBN 978-1-136-60310-5 Keown, Damien (2013a),

"Buddhism and Biomedical Issues" (PDF), in Emmanuel, Steven M. (ed.), A Companion to Buddhist Philosophy (1st ed.),

Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 613–30,

ISBN 978-0-470-65877-2 Keown, Damien (2013b), "Buddhist Ethics", in LaFollette, Hugh (ed.), The International Encyclopedia of Ethics,

Blackwell Publishing, pp. 636–47,

doi:

10.1002/9781444367072.wbiee163,

ISBN 978-1-4051-8641-4 Keown, Damien (2016a), "Buddhism and Abortion: Is There a 'Middle Way'?", in

Keown, Damien (ed.), Buddhism and Abortion,

Macmillan Press, pp. 199–218,

doi:

10.1007/978-1-349-14178-4,

ISBN 978-1-349-14178-4 Keown, Damien (2016b),

Buddhism and Bioethics,

Springer Nature,

ISBN 978-1-349-23981-8 Keown, Damien (2017), "It's Ethics, Jim, but Not as We Know It", in Davis, J.H. (ed.), A Mirror is for Reflection: Understanding Buddhist Ethics,

Oxford University Press, pp. 17–32

Kieschnick, John (2005),

"Buddhist Vegetarianism in China" (PDF), in Sterckx, R. (ed.), Of Tripod and Palate: Food, Politics, and Religion in Traditional China,

Springer Nature, pp. 186–212,

ISBN 978-1-4039-7927-8 Kohn, Livia (1994), "The Five Precepts of the Venerable Lord",

Monumenta Serica, 42 (1): 171–215,

doi:

10.1080/02549948.1994.11731253 Leaman, Oliver (2000),

Eastern Philosophy: Key Readings (PDF),

Routledge,

ISBN 978-0-415-17357-5,

archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2017

Ledgerwood, Judy (2008), "Buddhist practice in rural Kandal province 1960 and 2003", in Kent, Alexandra; Chandler, David (eds.), People of Virtue: Reconfiguring Religion, Power and Moral Order in Cambodia Today,

Nordic Institute of Asian Studies,

ISBN 978-87-7694-036-2 Ledgerwood, Judy; Un, Kheang (3 June 2010), "Global Concepts and Local Meaning: Human Rights and Buddhism in Cambodia", Journal of Human Rights, 2 (4): 531–49,

doi:

10.1080/1475483032000137129,

S2CID 144667807 MacKenzie, Matthew (December 2017), "Buddhism and the Virtues", in Snow, Nancy E. (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Virtue, 1,

Oxford University Press,

doi:

10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199385195.013.18 Mcdermott, J.P. (1 October 1989), "Animals and Humans in Early Buddhism",

Indo-Iranian Journal, 32 (4): 269–80,

doi:

10.1163/000000089790083303 Mcdermott, J.P. (2016), "Abortion in the Pali Canon and Early Buddhist Thought", in

Keown, Damien (ed.), Buddhism and Abortion,

Macmillan Press, pp. 157–82,

doi:

10.1007/978-1-349-14178-4,

ISBN 978-1-349-14178-4 McFarlane, Stewart (1997),

"Morals and Society in Buddhism" (PDF), in Carr, Brian; Mahalingam, Indira (eds.), Companion Encyclopedia of Asian Philosophy,

Routledge, pp. 407–22,

ISBN 978-0-203-01350-2,

archived (PDF) from the original on 3 August 2018

Meadow, Mary Jo (2006), "Buddhism: Theravāda Buddhism", in Riggs, Thomas (ed.), Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices,

Thomson Gale, pp. 83–92,

ISBN 978-0-7876-9390-9 Neumaier, Eva (2006), "Buddhism: Māhayāna Buddhism", in Riggs, Thomas (ed.), Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices,

Thomson Gale,

ISBN 978-0-7876-9390-9 Osto, Douglas (2015),

"Merit", in

Powers, John (ed.), The Buddhist World,

Routledge,

ISBN 978-1-317-42016-3 Perrett, Roy W. (July 2000), "Buddhism, Abortion and the Middle Way",

Asian Philosophy, 10 (2): 101–14,

doi:

10.1080/713650898,

S2CID 143808199 Powers, John (2013),

A Concise Encyclopedia of Buddhism,

Oneworld Publications,

ISBN 978-1-78074-476-6 Queen, Christopher S. (2013),

"Socially Engaged Buddhism: Emerging Patterns of Theory and Practice" (PDF), in Emmanuel, Steven M. (ed.), A Companion to Buddhist Philosophy,

Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 524–35,

ISBN 978-0-470-65877-2 Ratanakul, P. (1998), "Socio-Medical Aspects of Abortion in Thailand", in

Keown, Damien(ed.), Buddhism and Abortion,

Macmillan Press, pp. 53–66,

doi:

10.1007/978-1-349-14178-4,

ISBN 978-1-349-14180-7 Ratanakul, P. (2007), "The Dynamics of Tradition and Change in Theravada Buddhism", The Journal of Religion and Culture, 1 (1): 233–57,

CiteSeerX 10.1.1.505.2366,

ISSN 1905-8144 Schmithausen, Lambert (1999),

"Buddhist Attitudes Towards War", in Houben, Jan E. M.; van Kooij, Karel Rijk (eds.), Violence Denied: Violence, Non-Violence and the Rationalization of Violence in South Asian Cultural History,

Brill publishing, pp. 45–68,

ISBN 978-9004113442 Seeger, M. (2010),

"Theravāda Buddhism and Human Rights. Perspectives from Thai Buddhism" (PDF), in Meinert, Carmen; Zöllner, Hans-Bernd (eds.), Buddhist Approaches to Human Rights: Dissonances and Resonances, Transcript Verlag, pp. 63–92,

ISBN 978-3-8376-1263-9 Segall, Seth Robert (2003),

"Psychotherapy Practice as Buddhist Practice" (PDF), in Segall, Seth Robert (ed.), Encountering Buddhism: Western Psychology and Buddhist Teachings,

State University of New York Press, pp. 165–78,

ISBN 978-0-7914-8679-5 Spiro, Melford E. (1982),

Buddhism and Society: A Great Tradition and Its Burmese Vicissitudes,

University of California Press,

ISBN 978-0-520-04672-6 Swearer, Donald K. (2010),

The Buddhist World of Southeast Asia (PDF) (2nd ed.),

State University of New York Press,

ISBN 978-1-4384-3251-9 Tachibana, Shundō (1992),

The Ethics of Buddhism,

Psychology Press,

ISBN 978-0-7007-0230-5 Tambiah, Stanley Jeyaraja (1992),

Buddhism Betrayed?: Religion, Politics, and Violence in Sri Lanka,

University of Chicago Press,

ISBN 978-0-226-78950-7 Tedesco, F.M. (2004), "Teachings on Abortion in Theravāda and Mahāyāna Traditions and Contemporary Korean Practice" (PDF), International Journal of Buddhist Thought & Culture, 4

Terwiel, Barend Jan (2012),

Monks and Magic: Revisiting a Classic Study of Religious Ceremonies in Thailand (PDF),

Nordic Institute of Asian Studies,

ISBN 9788776941017,

archived (PDF) from the original on 19 August 2018

Vanphanom, Sychareun; Phengsavanh, Alongkon; Hansana, Visanou; Menorath, Sing; Tomson, Tanja (2009), "Smoking Prevalence, Determinants, Knowledge, Attitudes and Habits among Buddhist Monks in Lao PDR", BMC Research Notes, 2 (100): 100,

doi:

10.1186/1756-0500-2-100,

PMC 2704224,

PMID 19505329 Wai, Maurice Nyunt (2002),

Pañcasila and Catholic Moral Teaching: Moral Principles as Expression of Spiritual Experience in Theravada Buddhism and Christianity, Gregorian Biblical BookShop,

ISBN 9788876529207 Wijayaratna, Mohan (1990),

Buddhist monastic life: According to the Texts of the Theravāda Tradition (PDF),

Cambridge University Press,

ISBN 978-0-521-36428-7, archived from

the original (PDF) on 15 December 2017, retrieved 29 July 2018

Yeh, T.D.L. (2006),