Afterlife

This article uses texts from within a religion or faith system without referring to secondary sources that critically analyze them. (September 2021) |

| Part of a series on the |

| Philosophy of religion |

|---|

| Philosophy of religion article index |

The afterlife or life after death is a purported existence in which the essential part of an individual's stream of consciousness or identity continues to exist after the death of their physical body.[1] The surviving essential aspect varies between belief systems; it may be some partial element, or the entire soul or spirit, which carries with it one's personal identity.

In some views, this continued existence takes place in a spiritual realm, while in others, the individual may be reborn into this world and begin the life cycle over again, known as reincarnation, likely with no memory of what they have done in the past. In this latter view, such rebirths and deaths may take place over and over again continuously until the individual gains entry to a spiritual realm or otherworld. Major views on the afterlife derive from religion, esotericism and metaphysics.

Some belief systems, such as those in the Abrahamic tradition, hold that the dead go to a specific place (e.g. paradise or hell) after death, as determined by their god, based on their actions and beliefs during life. In contrast, in systems of reincarnation, such as those in the Indian religions, the nature of the continued existence is determined directly by the actions of the individual in the ended life.

Theist immortalists generally believe some afterlife awaits people when they die. Members of some generally non-theistic religions believe in an afterlife without reference to a deity.

Many religions, whether they believe in the soul's existence in another world like Christianity, Islam, and many pagan belief systems, or reincarnation like many forms of Hinduism and Buddhism, believe that one's status in the afterlife is a consequence of one's conduct during life.[citation needed]

Reincarnation is the philosophical or religious concept that an aspect of a living being starts a new life in a different physical body or form after each death. This concept is also known as rebirth or transmigration and is part of the Saṃsāra/karma doctrine of cyclic existence. Samsara refers to the process in which souls (jivas) go through a sequence of human and animal forms. Traditional Hinduism teaches that each life helps the soul (jivas) learn until the soul becomes purified to the point of liberation.[2] All major Indian religions, namely Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, and Sikhism have their own interpretations of the idea of reincarnation.[3] The human idea of reincarnation is found in many diverse ancient cultures,[4][5] and a belief in rebirth/metempsychosis was held by historic Greek figures, such as Pythagoras and Plato.[6] It is also a common belief of various ancient and modern religions such as Spiritism, theosophy, and Eckankar. It is found as well in many tribal societies around the world, in places such as Australia, East Asia, Siberia, and South America.[7]

Although the majority of denominations within the Abrahamic religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam do not believe that individuals reincarnate, particular groups within these religions do refer to reincarnation; these groups include the mainstream historical and contemporary followers of Kabbalah, the Cathars, Alawites, the Druze,[8] and the Rosicrucians.[9] The historical relations between these sects and the beliefs about reincarnation that were characteristic of neoplatonism, Orphism, Hermeticism, Manicheanism, and Gnosticism of the Roman era as well as the Indian religions have been the subject of recent scholarly research.[10] Unity Church and its founder Charles Fillmore teach reincarnation.

Rosicrucians[9] speak of a life review period occurring immediately after death and before entering the afterlife's planes of existence (before the silver cord is broken), followed by a judgment, more akin to a final review or end report over one's life.[11]

The neutrality of this article is disputed. (June 2023) |

Heaven, the heavens, Seven Heavens, pure lands, Tian, Jannah, Valhalla, or the Summerland, is a common religious, cosmological, or transcendent place where beings such as gods, angels, jinn, saints, or venerated ancestors are said to originate, be enthroned, or live. According to the beliefs of some religions, heavenly beings can descend to earth or incarnate, and earthly beings can ascend to heaven in the afterlife, or in exceptional cases, enter heaven alive.

Heaven is often described as a "higher place", the holiest place, a paradise, in contrast to hell or the underworld or the "low places", and universally or conditionally accessible by earthly beings according to various standards of divinity, goodness, piety, faith or other virtues or right beliefs or the will of God. Some believe in the possibility of a heaven on Earth in a world to come.

In Hinduism, heaven is considered as Svarga loka. There are seven positive regions the soul can go to after death and seven negative regions.[12] After completing its stay in the respective region, the soul is subjected to rebirth in different living forms according to its karma. This cycle can be broken after a soul achieves Moksha or Nirvana. Any place of existence, either of humans, souls or deities, outside the tangible world (heaven, hell, or other) is referred to as otherworld.

Hell, in many religious and folkloric traditions, is a place of torment and punishment in the afterlife. Religions with a linear divine history often depict hell as an eternal destination, while religions with a cyclic history often depict a hell as an intermediary period between incarnations. Typically, these traditions locate hell in another dimension or under the Earth's surface and often include entrances to hell from the land of the living. Other afterlife destinations include purgatory and limbo.

Traditions that do not conceive of the afterlife as a place of punishment or reward merely describe hell as an abode of the dead, the grave, a neutral place (for example, Sheol or Hades) located under the surface of Earth.[13]

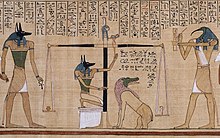

The afterlife played an important role in Ancient Egyptian religion, and its belief system is one of the earliest known in recorded history. When the body died, parts of its soul known as ka (body double) and the ba (personality) would go to the Kingdom of the Dead. While the soul dwelt in the Fields of Aaru, Osiris demanded work as restitution for the protection he provided. Statues were placed in the tombs to serve as substitutes for the deceased.[14]

Arriving at one's reward in afterlife was a demanding ordeal, requiring a sin-free heart and the ability to recite the spells, passwords, and formulae of the Book of the Dead. In the Hall of Two Truths, the deceased's heart was weighed against the Shu feather of truth and justice taken from the headdress of the goddess Ma'at.[15] If the heart was lighter than the feather, they could pass on, but if it were heavier they would be devoured by the demon Ammit.[16]

Egyptians also believed that being mummified and put in a sarcophagus (an ancient Egyptian "coffin" carved with complex symbols and designs, as well as pictures and hieroglyphs) was the only way to have an afterlife. What are referred to as the Coffin Texts, are inscribed on a coffin and serve as a guide for the challenges in the afterlife. The Coffin texts are more or less a duplication of the Pyramid Texts, which would serve as a guide for Egyptian pharaohs or queens in the afterlife.[17] Only if the corpse had been properly embalmed and entombed in a mastaba, could the dead live again in the Fields of Yalu and accompany the Sun on its daily ride. Due to the dangers the afterlife posed, the Book of the Dead was placed in the tomb with the body as well as food, jewelry, and 'curses'. They also used the "opening of the mouth".[18][19]

Ancient Egyptian civilization was based on religion. The belief in the rebirth after death became the driving force behind funeral practices; for them, death was a temporary interruption rather than complete cessation of life. Eternal life could be ensured by means like piety to the gods, preservation of the physical form through mummification, and the provision of statuary and other funerary equipment. Each human consisted of the physical body, the ka, the ba, and the akh. The Name and Shadow were also living entities. To enjoy the afterlife, all these elements had to be sustained and protected from harm.[20]

On 30 March 2010, a spokesman for the Egyptian Culture Ministry claimed it had unearthed a large red granite door in Luxor with inscriptions by User,[21] a powerful adviser to the 18th Dynasty Queen Hatshepsut who ruled between 1479 BC and 1458 BC, the longest of any woman. It believes the false door is a 'door to the Afterlife'. According to the archaeologists, the door was reused in a structure in Roman Egypt.

The Greek god Hades is known in Greek mythology as the king of the underworld, a place where souls live after death.[22] The Greek god Hermes, the messenger of the gods, would take the dead soul of a person to the underworld (sometimes called Hades or the House of Hades). Hermes would leave the soul on the banks of the River Styx, the river between life and death.[23]

Charon, also known as the ferry-man, would take the soul across the river to Hades, if the soul had gold: Upon burial, the family of the dead soul would put coins under the deceased's tongue. Once crossed, the soul would be judged by Aeacus, Rhadamanthus and King Minos. The soul would be sent to Elysium, Tartarus, or Asphodel Fields. The Elysian Fields were for the ones that lived pure lives. It consisted of green fields, valleys and mountains, everyone there was peaceful and contented, and the Sun always shone there. Tartarus was for the people that blasphemed against the gods or were rebellious and consciously evil.[24] In Tartarus, the soul would be punished by being burned in lava or stretched on racks. The Asphodel Fields were for a varied selection of human souls including those whose sins equaled their goodness, those who were indecisive in their lives, and those who were not judged.

Some heroes of Greek legend are allowed to visit the underworld. The Romans had a similar belief system about the afterlife, with Hades becoming known as Pluto. In the ancient Greek myth about the Labours of Heracles, the hero Heracles had to travel to the underworld to capture Cerberus, the three-headed guard dog, as one of his tasks.

In Dream of Scipio, Cicero describes what seems to be an out of body experience, of the soul traveling high above the Earth, looking down at the small planet, from far away.[25]

In Book VI of Virgil's Aeneid, the hero, Aeneas, travels to the underworld to see his father. By the River Styx, he sees the souls of those not given a proper burial, forced to wait by the river until someone buries them. While down there, along with the dead, he is shown the place where the wrongly convicted reside, the fields of sorrow where those who committed suicide and now regret it reside, including Aeneas' former lover, the warriors and shades, Tartarus (where the titans and powerful non-mortal enemies of the Olympians reside) where he can hear the groans of the imprisoned, the palace of Pluto, and the fields of Elysium where the descendants of the divine and bravest heroes reside. He sees the river of forgetfulness, Lethe, which the dead must drink to forget their life and begin anew. Lastly, his father shows him all of the future heroes of Rome who will live if Aeneas fulfills his destiny in founding the city.

Other eschatological views populate the ancient-Greek worldview. For instance, Plato argued for reincarnation in several dialogues, including the Timaeus.[26]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2017) |

The Poetic and Prose Eddas, the oldest sources for information on the Norse concept of the afterlife, vary in their description of the several realms that are described as falling under this topic. The most well-known are:

- Valhalla: (lit. "Hall of the Slain" i.e. "the Chosen Ones") Half the warriors who die in battle join the god Odin who rules over a majestic hall called Valhalla in Asgard.[27]

- Fólkvangr: (lit. "Field of the Host") The other half join the goddess Freyja in a great meadow known as Fólkvangr.[28]

- Niflhel: (lit. "The Dark" or "Misty Hel"). Niflhel is believed to be a place of punishment, where the oathbreakers and other wicked people go.

- Hel: (lit. "The Covered Hall"). Hel was the daughter of god Loki and her kingdom was located in downward and northward. Snorri Sturluson's Gylfaginning tells of evil men going to Niflhel via Hel.

Sheol, in the Hebrew Bible, is a place of darkness (Job x. 21, 22) to which all the dead go, both the righteous and the unrighteous, regardless of the moral choices made in life (Gen. xxxvii. 36; Ezek. xxxii.; Isa. xiv.; Job xxx. 23), a place of stillness (Ps. lxxxviii. 13, xciv. 17; Eccl. ix. 10), at the longest possible distance from heaven (Job xi. 8; Amos ix. 2; Ps. cxxxix. 8).[29]

The inhabitants of Sheol were the "shades" (rephaim), entities without personality or strength. Under some circumstances they were thought to be able to be contacted by the living, as the Witch of Endor contacts the shade of Samuel for Saul, but such practices were forbidden (Deuteronomy 18:10).[30]

While the Hebrew Bible appears to describe Sheol as the permanent place of the dead, in the Second Temple period (roughly 500 BC – 70 AD) a more diverse set of ideas developed. In some texts, Sheol is considered to be the home of both the righteous and the wicked, separated into respective compartments; in others, it was considered a place of punishment, meant for the wicked dead alone.[31] When the Hebrew scriptures were translated into Greek in ancient Alexandria around 200 BC, the word "Hades" (the Greek underworld) was substituted for Sheol. This is reflected in the New Testament where Hades is both the underworld of the dead and the personification of the evil it represents.[31][32]

The Talmud offers several thoughts relating to the afterlife. After death, the soul is brought for judgment. Those who have led pristine lives enter immediately into the Olam Haba or world to come. Most do not enter the world to come immediately, but experience a period of reflection of their earthly actions and are made aware of what they have done wrong. Some view this period as being a "re-schooling", with the soul gaining wisdom as one's errors are reviewed. Others view this period to include spiritual discomfort for past wrongs. At the end of this period, not longer than one year, the soul then takes its place in the world to come. Although discomforts are made part of certain Jewish conceptions of the afterlife, the concept of eternal damnation is not a tenet of the Jewish afterlife. According to the Talmud, extinction of the soul is reserved for a far smaller group of malicious and evil leaders, either whose very evil deeds go way beyond norms, or who lead large groups of people to utmost evil.[33][34] This is also part of Maimonides' 13 principles of faith.[35]

Maimonides describes the Olam Haba in spiritual terms, relegating the prophesied physical resurrection to the status of a future miracle, unrelated to the afterlife or the Messianic era. According to Maimonides, an afterlife continues for the soul of every human being, a soul now separated from the body in which it was "housed" during its earthly existence.[36]

The Zohar describes Gehenna not as a place of punishment for the wicked but as a place of spiritual purification for souls.[37]

Although there is no reference to reincarnation in the Talmud or any prior writings,[38] according to rabbis such as Avraham Arieh Trugman, reincarnation is recognized as being part and parcel of Jewish tradition. Trugman explains that it is through oral tradition that the meanings of the Torah, its commandments and stories, are known and understood. The classic work of Jewish mysticism,[39] the Zohar, is quoted liberally in all Jewish learning; in the Zohar the idea of reincarnation is mentioned repeatedly. Trugman states that in the last five centuries the concept of reincarnation, which until then had been a much hidden tradition within Judaism, was given open exposure.[39]

Shraga Simmons commented that within the Bible itself, the idea [of reincarnation] is intimated in Deut. 25:5–10, Deut. 33:6 and Isaiah 22:14, 65:6.[40]

Yirmiyahu Ullman wrote that reincarnation is an "ancient, mainstream belief in Judaism". The Zohar makes frequent and lengthy references to reincarnation. Onkelos, a righteous convert and authoritative commentator of the same period, explained the verse, "Let Reuben live and not die ..." (Deuteronomy 33:6) to mean that Reuben should merit the World to Come directly, and not have to die again as a result of being reincarnated. Torah scholar, commentator and kabbalist, Nachmanides (Ramban 1195–1270), attributed Job's suffering to reincarnation, as hinted in Job's saying "God does all these things twice or three times with a man, to bring back his soul from the pit to... the light of the living' (Job 33:29, 30)."[41]

Reincarnation, called gilgul, became popular in folk belief, and is found in much Yiddish literature among Ashkenazi Jews. Among a few kabbalists, it was posited that some human souls could end up being reincarnated into non-human bodies. These ideas were found in a number of Kabbalistic works from the 13th century, and also among many mystics in the late 16th century. Martin Buber's early collection of stories of the Baal Shem Tov's life includes several that refer to people reincarnating in successive lives.[42]

Among well known (generally non-kabbalist or anti-kabbalist) rabbis who rejected the idea of reincarnation are Saadia Gaon, David Kimhi, Hasdai Crescas, Yedayah Bedershi (early 14th century), Joseph Albo, Abraham ibn Daud, the Rosh and Leon de Modena. Saadia Gaon, in Emunoth ve-Deoth (Hebrew: "beliefs and opinions") concludes Section VI with a refutation of the doctrine of metempsychosis (reincarnation). While rebutting reincarnation, Saadia Gaon further states that Jews who hold to reincarnation have adopted non-Jewish beliefs. By no means do all Jews today believe in reincarnation, but belief in reincarnation is not uncommon among many Jews, including Orthodox.

Other well-known rabbis who are reincarnationists include Yonassan Gershom, Abraham Isaac Kook, Talmud scholar Adin Steinsaltz, DovBer Pinson, David M. Wexelman, Zalman Schachter,[43] and many others. Reincarnation is cited by authoritative biblical commentators, including Ramban (Nachmanides), Menachem Recanti and Rabbenu Bachya.

Among the many volumes of Yitzchak Luria, most of which come down from the pen of his primary disciple, Chaim Vital, are insights explaining issues related to reincarnation. His Shaar HaGilgulim, "The Gates of Reincarnation", is a book devoted exclusively to the subject of reincarnation in Judaism.

Rabbi Naftali Silberberg of The Rohr Jewish Learning Institute notes that "Many ideas that originate in other religions and belief systems have been popularized in the media and are taken for granted by unassuming Jews."[44]

This section relies excessively on references to primary sources. (July 2017) |

Mainstream Christianity professes belief in the Nicene Creed, and English versions of the Nicene Creed in current use include the phrase: "We look for the resurrection of the dead, and the life of the world to come."

When questioned by the Sadducees about the resurrection of the dead (in a context relating to who one's spouse would be if one had been married several times in life), Jesus said that marriage will be irrelevant after the resurrection as the resurrected will be like the angels in heaven.[45][46]

Jesus also maintained that the time would come when the dead would hear the voice of the Son of God, and all who were in the tombs would come out; those who have heard His "[commandments] and believes in the one who sent [Him]" to the resurrection of life, but those who do not to the resurrection of condemnation.[47]

The Book of Enoch describes Sheol as divided into four compartments for four types of the dead: the faithful saints who await resurrection in Paradise, the merely virtuous who await their reward, the wicked who await punishment, and the wicked who have already been punished and will not be resurrected on Judgment Day.[48] The Book of Enoch is considered apocryphal by most denominations of Christianity and Judaism.

The book of 2 Maccabees gives a clear account of the dead awaiting a future resurrection and judgment in addition to prayers and offerings for the dead to remove the burden of sin.

The author of Luke recounts the story of Lazarus and the rich man, which shows people in Hades awaiting the resurrection either in comfort or torment. The author of the Book of Revelation John, writes about God and the angels versus Satan and demons in an epic battle at the end of times when all souls are judged. There is mention of ghostly bodies of past prophets, and the transfiguration.

The non-canonical Acts of Paul and Thecla speak of the efficacy of prayer for the dead so that they might be "translated to a state of happiness".[49]

Hippolytus of Rome pictures the underworld (Hades) as a place where the righteous dead, awaiting in the bosom of Abraham their resurrection, rejoice at their future prospect, while the unrighteous are tormented at the sight of the "lake of unquenchable fire" into which they are destined to be cast.

Gregory of Nyssa discusses the long-before believed possibility of purification of souls after death.[50]

Pope Gregory I repeats the concept, articulated over a century earlier by Gregory of Nyssa that the saved suffer purification after death, in connection with which he wrote of "purgatorial flames".

The noun "purgatorium" (Latin: place of cleansing[51]) is used for the first time to describe a state of painful purification of the saved after life. The same word in adjectival form (purgatorius -a -um, cleansing), which appears also in non-religious writing,[52] was already used by Christians such as Augustine of Hippo and Pope Gregory I to refer to an after-death cleansing.

During the Age of Enlightenment, theologians and philosophers presented various philosophies and beliefs. A notable example is Emanuel Swedenborg who wrote some 18 theological works which describe in detail the nature of the afterlife according to his claimed spiritual experiences, the most famous of which is Heaven and Hell.[53] His report of life there covers a wide range of topics, such as marriage in heaven (where all angels are married), children in heaven (where they are raised by angel parents), time and space in heaven (there are none), the after-death awakening process in the World of Spirits (a place halfway between Heaven and Hell and where people first wake up after death), the allowance of a free will choice between Heaven or Hell (as opposed to being sent to either one by God), the eternity of Hell (one could leave but would never want to), and that all angels or devils were once people on earth.[53]

The Catholic conception of the afterlife teaches that after the body dies, the soul is judged, the righteous and free of sin enter Heaven. However, those who die in unrepented mortal sin go to hell. In the 1990s, the Catechism of the Catholic Church defined hell not as punishment imposed on the sinner but rather as the sinner's self-exclusion from God. Unlike other Christian groups, the Catholic Church teaches that those who die in a state of grace, but still carry venial sin, go to a place called Purgatory where they undergo purification to enter Heaven.

Despite popular opinion, Limbo, which was elaborated upon by theologians beginning in the Middle Ages, was never recognized as a dogma of the Catholic Church, yet, at times, it has been a very popular theological theory within the Church. Limbo is a theory that unbaptized but innocent souls, such as those of infants, virtuous individuals who lived before Jesus Christ was born on earth, or those that die before baptism exist in neither Heaven nor Hell proper. Therefore, these souls neither merit the beatific vision, nor are subjected to any punishment, because they are not guilty of any personal sin although they have not received baptism, so still bear original sin. So they are generally seen as existing in a state of natural, but not supernatural, happiness, until the end of time.

In other Christian denominations it has been described as an intermediate place or state of confinement in oblivion and neglect.[54]

The notion of purgatory is associated particularly with the Catholic Church. In the Catholic Church, all those who die in God's grace and friendship, but still imperfectly purified, are indeed assured of their eternal salvation; but after death they undergo purification, so as to achieve the holiness necessary to enter the joy of heaven or the final purification of the elect, which is entirely different from the punishment of the damned. The tradition of the church, by reference to certain texts of scripture, speaks of a "cleansing fire" although it is not always called purgatory.

Anglicans of the Anglo-Catholic tradition generally also hold to the belief. John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, believed in an intermediate state between death and the resurrection of the dead and in the possibility of "continuing to grow in holiness there", but Methodism does not officially affirm this belief and denies the possibility of helping by prayer any who may be in that state.[55]

The Orthodox Church is intentionally reticent on the afterlife, as it acknowledges the mystery especially of things that have not yet occurred. Beyond the second coming of Jesus, bodily resurrection, and final judgment, all of which is affirmed in the Nicene Creed (325 AD), Orthodoxy does not teach much else in any definitive manner. Unlike Western forms of Christianity, however, Orthodoxy is traditionally non-dualist and does not teach that there are two separate literal locations of heaven and hell, but instead acknowledges that "the 'location' of one's final destiny—heaven or hell—as being figurative."[56]

Instead, Orthodoxy teaches that the final judgment is one's uniform encounter with divine love and mercy, but this encounter is experienced multifariously depending on the extent to which one has been transformed, partaken of divinity, and is therefore compatible or incompatible with God. "The monadic, immutable, and ceaseless object of eschatological encounter is therefore the love and mercy of God, his glory which infuses the heavenly temple, and it is the subjective human reaction which engenders multiplicity or any division of experience."[56] For instance, St. Isaac the Syrian observes in his Ascetical Homilies that "those who are punished in Gehenna, are scourged by the scourge of love. ... The power of love works in two ways: it torments sinners ... [as] bitter regret. But love inebriates the souls of the sons of Heaven by its delectability."[57] In this sense, the divine action is always, immutably, and uniformly love and if one experiences this love negatively, the experience is then one of self-condemnation because of free will rather than condemnation by God.

Orthodoxy therefore uses the description of Jesus' judgment in John 3:19–21 as their model: "19 And this is the judgment: the light has come into the world, and people loved the darkness rather than the light because their works were evil. 20 For everyone who does wicked things hates the light and does not come to the light, lest his works should be exposed. 21 But whoever does what is true comes to the light, so that it may be clearly seen that his works have been carried out in God." As a characteristically Orthodox understanding, then, Fr. Thomas Hopko writes, "[I]t is precisely the presence of God's mercy and love which cause the torment of the wicked. God does not punish; he forgives... . In a word, God has mercy on all, whether all like it or not. If we like it, it is paradise; if we do not, it is hell. Every knee will bend before the Lord. Everything will be subject to Him. God in Christ will indeed be "all and in all," with boundless mercy and unconditional pardon. But not all will rejoice in God's gift of forgiveness, and that choice will be judgment, the self-inflicted source of their sorrow and pain."[58]

Moreover, Orthodoxy includes a prevalent tradition of apokatastasis, or the restoration of all things in the end. This has been taught most notably by Origen, but also many other Church fathers and Saints, including Gregory of Nyssa. The Second Council of Constantinople (553 AD) affirmed the orthodoxy of Gregory of Nyssa while simultaneously condemning Origen's brand of universalism because it taught the restoration back to our pre-existent state, which Orthodoxy does not teach. It is also a teaching of such eminent Orthodox theologians as Olivier Clément, Metropolitan Kallistos Ware, and Bishop Hilarion Alfeyev.[59] Although apokatastasis is not a dogma of the church but instead a theologoumenon, it is no less a teaching of the Orthodox Church than its rejection. As Met. Kallistos Ware explains, "It is heretical to say that all must be saved, for this is to deny free will; but, it is legitimate to hope that all may be saved,"[60] as insisting on torment without end also denies free will.

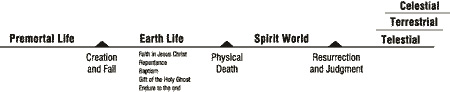

Joseph F. Smith of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints presents an elaborate vision of the afterlife. It is revealed as the scene of an extensive missionary effort by righteous spirits in paradise to redeem those still in darkness—a spirit prison or "hell" where the spirits of the dead remain until judgment. It is divided into two parts: Spirit Prison and Paradise. Together these are also known as the Spirit World (also Abraham's Bosom; see Luke 16:19–25). They believe that Christ visited spirit prison (1 Peter 3:18–20) and opened the gate for those who repent to cross over to Paradise. This is similar to the Harrowing of Hell doctrine of some mainstream Christian faiths.[61] Both Spirit Prison and Paradise are temporary according to Latter-day Saint beliefs. After the resurrection, spirits are assigned "permanently" to three degrees of heavenly glory, determined by how they lived – Celestial, Terrestrial, and Telestial. (1 Cor 15:44–42; Doctrine and Covenants, Section 76) Sons of Perdition, or those who have known and seen God and deny it, will be sent to the realm of Satan, which is called Outer Darkness, where they shall live in misery and agony forever.[62] However, according to the beliefs of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, most persons lack the amount of knowledge to commit the Eternal sin and are therefore incapable of becoming sons of perdition.[63]

The Celestial Kingdom is believed to be a place where the righteous can live eternally with their families. Progression does not end once one has entered the Celestial Kingdom, but extends eternally. According to "True to the Faith" (a handbook on doctrines in the LDS faith), "The celestial kingdom is the place prepared for those who have "received the testimony of Jesus" and been "made perfect through Jesus the mediator of the new covenant, who wrought out this perfect atonement through the shedding of his own blood" (Doctrine and Covenants, 76:51, 69). To inherit this gift, we must receive the ordinances of salvation, keep the commandments, and repent of our sins."[64]

Jehovah's Witnesses occasionally use terms such as "afterlife"[65] to refer to any hope for the dead, but they understand Ecclesiastes 9:5 to preclude belief in an immortal soul.[66] Individuals judged by God to be wicked, such as in the Great Flood or at Armageddon, are given no hope of an afterlife. However, they believe that after Armageddon there will be a bodily resurrection of "both righteous and unrighteous" dead (but not the "wicked"). Survivors of Armageddon and those who are resurrected are then to gradually restore earth to a paradise.[67] After Armageddon, unrepentant sinners are punished with eternal death (non-existence).

The Seventh-day Adventist Church's beliefs regarding the afterlife differ from other Christian churches. Rather than ascend to Heaven or descend to Hell, Adventists believe the dead "remain unconscious until the return of Christ in judgement". The concept that the dead remain dead until resurrection is one of the fundamental beliefs of Seventh-day Adventism.[68] Adventists believe that death is an unconscious state (a "sleep"). This is based on Matt. 9:24; Mark 5:39; John 11:11–14; 1 Cor. 15:51, 52; 1 Thess. 4:13–17; 2 Peter 3:4; Eccl. 9:5, 6, 10. At death, all consciousness ends. The dead person does not know anything and does not do anything.[69] They believe that death is a decreation, or an undoing of what was created. This is described in Ecclesiastes 12:7: "When a person dies, the body turns to dust again, and the spirit goes back to God, who gave it." The spirit of every person who dies—whether saved or unsaved—returns to God at death. The spirit that returns to God at death is the breath of life.[70]

The Quran (the holy book of Islam) emphasizes the insignificance of worldly life (ḥayāt ad-dunyā usually translated as "this world") vis-a-vis the hereafter.[Note 1] A central doctrine of Islamic faith is the Judgement Day (al-yawm al-ākhir, also known by other names),[Note 2] on which the world will come to an end and God will raise all mankind (as well as the jinn) from the dead and evaluate their worldly actions. The resurrected will be judged according to their deeds, records of which are kept on two books compiled for every human being—one for their good deeds and one for their evil ones.[72][46]

Having been judged, the resurrected will cross the bridge of As-Sirāt over the pit of hell; when the condemned attempt to they will be made to fall off into hellfire below, while the righteous will have no trouble and continue on to their eternal abode of heaven.[73]

Afterlife in Islam actually begins before the Last Day. After death, humans will be questioned about their faith by two angels, Munkar and Nakīr. Those who die as martyrs go immediately to paradise.[72] Others who have died and been buried will receive a taste of their eternal reward from the al-qabr or "the grave" (compare the Jewish concept of Sheol). Those bound for hell will suffer "Punishment of the Grave", while those bound for heaven will find the grave "peaceful and blessed".[74]

Islamic scripture—the Quran and hadith (reports of the words and deeds of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad who is believed to have visited heaven and hell during his Isra and Mi'raj journey) – give vivid descriptions of the pleasures of paradise (Jannah) and sufferings of hell (Jahannam). The gardens of jannah have cool shade [Quran 36:56–57] adorned couchs and cushions [ 18:31] rich carpets spread out, cups [ 88:10–16] full of wine [ 52:23] and every meat [ 52:22] and fruit [ 36:56–57]. Men will be provided with perpetually youthful, beautiful ḥūr, "untouched beforehand by man or jinn",[75][ 55:56] with large, beautiful eyes [ 37:48]. (In recent years some have argued that the term ḥūr refers both to pure men and pure women,[76] and/or that Quranic references to "immortal boys" (56:17, 76:19) or "young men" (52:24) (ghilmān, wildān, and suqāh) who serve wine and meals to the blessed, are the male equivalents of hur.)[75]

In contrast, those in Jahannam will dwell in a land infested with thousands of serpents and scorpions;[77] be "burnt" by "scorching fire" [ 88:1-7] and when "their skins are roasted through, We shall change them for fresh skins" to repeat the process forever [ 4:56]; they will have nothing to drink but "boiling water and running sores"[ 78:21–30];[78] their cries of remorse and pleading for forgiveness will be in vain[ 26:96–106].[79][80]

Traditionally Jannah and Jahannam are thought to have different levels. Eight gates and eight levels in Jannah, where the higher the level the better it is and the happier you are. Jahannam possess seven layers. Each layer more horrible than the one above.

The Quran teaches that the purpose of Man's creation is to worship God and God alone.[Note 3] Those it describes as being punished in hell are "most typically" unbelievers, including those who worship others besides Allah [ 10:24], those who deny the divine origin of the Quran [ 74:16–26], or the coming of Judgement Day [ 25:11–14].[81][82]: 404

Straightforward crimes/sins against other people are also grounds for going to hell: the murder of a believer [ 4:93][ 3:21], usury (Q.2:275)[ 2:275], devouring the property of an orphan [ 4:10], and slander [Quran 104], particularly of a chaste woman [ 24:23].[83] However, it is a common belief among Muslims that whatever crimes/sins Muslims may have committed, their punishment in hell will be temporary. Only unbelievers will reside in hell permanently.[84][Note 4] Thus Jahannam combines both the concept of an eternal hell (for unbelievers), and what is known in Christian Catholicism as purgatory (for believers eventually destined for heaven after punishment for their sins).[87]

The common belief holds that Jahannam coexists with the temporal world.[88] Mainstream Islam teaches the continued existence of the soul and a transformed physical existence after death. The resurrection that will take place on the Last Day is physical, and is explained by suggesting that God will re-create the decayed body ("Have they not realized that Allah, Who created the heavens and the earth, can ˹easily˺ re-create them?" [ 17:99]).

Ahmadi Muslims believe that the afterlife is not material but of a spiritual nature. According to Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, founder of the Ahmadiyya, the soul will give birth to another rarer entity and will resemble the life on this earth in the sense that this entity will bear a similar relationship to the soul as the soul bears relationship with the human existence on earth. On earth, if a person leads a righteous life and submits to the will of God, his or her tastes become attuned to enjoying spiritual pleasures as opposed to carnal desires. With this, an "embryonic soul" begins to take shape. Different tastes are said to be born which a person given to carnal passions finds no enjoyment. For example, sacrifice of one's own rights over that of others becomes enjoyable, or that forgiveness becomes second nature. In such a state a person finds contentment and peace at heart and at this stage, according to Ahmadiyya beliefs, it can be said that a soul within the soul has begun to take shape.[89]

The Sufi Muslim scholar Ibn 'Arabi defined Barzakh as the intermediate realm or "isthmus". It is between the world of corporeal bodies and the world of spirits, and is a means of contact between the two worlds. Without it, there would be no contact between the two and both would cease to exist. He described it as simple and luminous, like the world of spirits, but also able to take on many different forms just like the world of corporeal bodies can. In broader terms Barzakh, "is anything that separates two things". It has been called the dream world in which the dreamer is in both life and death.[90]

The teachings of the Baháʼí Faith state that the nature of the afterlife is beyond the understanding of those living, just as an unborn fetus cannot understand the nature of the world outside of the womb. The Baháʼí writings state that the soul is immortal and after death it will continue to progress until it finally attains God's presence.[91] In Baháʼí belief, souls in the afterlife will continue to retain their individuality and consciousness and will be able to recognize and communicate spiritually with other souls whom they have made deep profound friendships with, such as their spouses.[92]

The Baháʼí scriptures also state there are distinctions between souls in the afterlife, and that souls will recognize the worth of their own deeds and understand the consequences of their actions. It is explained that those souls that have turned toward God will experience gladness, while those who have lived in error will become aware of the opportunities they have lost. Also, in the Baháʼí view, souls will be able to recognize the accomplishments of the souls that have reached the same level as themselves, but not those that have achieved a rank higher than them.[92]

Early Indian religions were characterized by the belief in an afterlife, Ancestor worship, and related rites. These concepts started to significantly change after the period of the Upanishads.[93]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2014) |

Afterlife in Buddhism consists of intermediated spirit realm that's beyond spatial means, which includes the six realms of existence, the 31 planes of existence, Naraka, Tengoku and the pure land after achieving enlightenment. Ancestor worship, and links to one's ancestors, was once an important component of early Buddhism, but became less relevant already before the formation of the different Buddhist streams. The concepts and importance of afterlife vary among modern Buddhist teachings.[94][95]

Buddhists maintain that rebirth takes place without an unchanging self or soul passing from one form to another.[96] The type of rebirth will be conditioned by the moral tone of the person's actions (kamma or karma). For example, if a person has committed harmful actions by body, speech and mind based on greed, hate and delusion, would have his/her rebirth in a lower realm, i.e. an animal, a hungry ghost or a hell realm, is to be expected. On the other hand, where a person has performed skillful actions based on generosity, loving-kindness (metta), compassion and wisdom, rebirth in a happy realm, i.e. human or one of the many heavenly realms, can be expected.[97]

However, the mechanism of rebirth with Kamma is not deterministic. It depends on various levels of kamma. The most important moment that determines where a person is reborn into is the last thought moment. At that moment, heavy kamma would ripen if there were performed. If not, near death kamma would ripen, and if not death kamma, then habitual kamma would ripen. Finally if none of the above happened, then residual kamma from previous actions can ripen.[98] According to Theravada Buddhism, there are 31 realms of existence that one can be reborn into. According to these, 31 existences comprise 20 existences of supreme deities (Brahmas); 6 existences of deities (Devas); the human existence (Manussa); and, lastly, 4 existences of deprivation or unhappiness (Apaya).

Pure Land Buddhism of Mahayana believes in a special place apart from the 31 planes of existence called Pure Land. It is believed that each Buddha has their own pure land, created out of their merits for the sake of sentient beings who recall them mindfully to be able to be reborn in their pure land and train to become a Buddha there. Thus the main practice of pure land Buddhism is to chant a Buddha's name.

In Tibetan Buddhism the Tibetan Book of the Dead explains the intermediate state of humans between death and reincarnation. The deceased will find the bright light of wisdom, which shows a straightforward path to move upward and leave the cycle of reincarnation. There are various reasons why the deceased do not follow that light. Some had no briefing about the intermediate state in the former life. Others only used to follow their basic instincts like animals. And some have fear, which results from foul deeds in the former life or from insistent haughtiness. In the intermediate state the awareness is very flexible, so it is important to be virtuous, adopt a positive attitude, and avoid negative ideas. Ideas which are rising from subconsciousness can cause extreme tempers and cowing visions. In this situation they have to understand, that these manifestations are just reflections of the inner thoughts. No one can really hurt them, because they have no more material body. The deceased get help from different Buddhas who show them the path to the bright light. The ones who do not follow the path after all will get hints for a better reincarnation. They have to release the things and beings on which or whom they still hang from the life before. It is recommended to choose a family where the parents trust in the Dharma and to reincarnate with the will to care for the welfare of all beings.

There are two major views of an afterlife in Hinduism: mythical and philosophical. The philosophies of Hinduism consider each individual consists of three bodies: physical body compose of water and bio-matter (sthūla śarīra), an energetic/psychic/mental/subtle body (sūkṣma-śarīra) and a causal body (kāraṇa śarīra) comprising subliminal stuff i.e. mental impressions etc.[99]

The individual is a stream of consciousness (Ātman), which flows through all the physical changes of the body and at the death of the physical body, flows on into another physical body. The two components that transmigrate are the subtle body and the causal body.

The thought that occupies the mind at the time of death determines the quality of our rebirth (antim smaraṇa)[1], hence Hinduism advises to be mindful of one's thoughts and cultivate positive wholesome thoughts – mantra chanting (japa) is commonly practiced for this.

The mythical includes the philosophical but adds heaven and hell myths.

When one leaves the physical body at death he appears in the court of Yama, the God of Death, for an exit interview. The panel consists of Yama and Chitragupta – the cosmic accountant, he has a book which consists the history of the dead persons according to his/her mistakes the Yama decides the punishment is and Varuna, the cosmic intelligence officer. He is counseled about his life, achievements and failures and is shown a mirror in which his entire life is reflected. Philosophically, these three men are projections of one's mind. Yama sends him to a heavenly realm (Svarga) if he has been exceptionally benevolent and beneficent for a period of rest and recreation. His period is limited in time by the weight of his good deeds. If he has been exceptionally malevolent and caused immense suffering to other beings, then he is sent to a hell realm (Naraka) for his sins. After one has exhausted his karma, he takes birth again to continue his spiritual evolution. However, the belief in rebirth was not a part of early Vedic religions and texts. It was later developed by rishis (sages) who challenged the idea of one's life as being simplistic.

Rebirth can take place as a god (deva), a human (manuṣya) an animal (tiryak)—but it is generally taught that the spiritual evolution takes place from lower to higher species. In certain cases of traumatic death a person can take the form of a preta or hungry ghost – and remains in an earth-bound state interminably – until certain ceremonies are done to liberate them. This mythological part is extensively elaborated in the Puranas, especially in the Garuda Purana.

The Upanishads are the first scriptures in Hinduism which explicitly mention the afterlife.[100] The Bhagavad Gita, a famous Hindu scripture, says that just as a man discards his old clothes and wears new ones; similarly the Atman discards the old body and takes on a new one. In Hinduism, the belief is that the body is nothing but a shell, the consciousness inside is immutable and indestructible and takes on different lives in a cycle of birth and death. The end of this cycle is called mukti (Sanskrit: मुक्ति) and staying finally with the ultimate reality forever is moksha (Sanskrit: मोक्ष) or liberation.

The (diverse) views of modern Hinduism in part differ significantly from the Historical Vedic religion.[94]

Jainism also believes in the afterlife. They believe that the soul takes on a body form based on previous karmas or actions performed by that soul through eternity. Jains believe the soul is eternal and that the freedom from the cycle of reincarnation is the means to attain eternal bliss.[101]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2014) |

The essential doctrine of Sikhism is to experience the divine through simple living, meditation, and contemplation while being alive. Sikhism also has the belief of being in union with God while living. Accounts of afterlife are considered to be aimed at the popular prevailing views of the time so as to provide a referential framework without necessarily establishing a belief in the afterlife. Thus while it is also acknowledged that living the life of a householder is above the metaphysical truth, Sikhism can be considered agnostic to the question of an afterlife. Some scholars also interpret the mention of reincarnation to be naturalistic akin to the biogeochemical cycles.[102]

But if one analyses the Sikh Scriptures carefully, one may find that on many occasions the afterlife and the existence of heaven and hell are mentioned and criticised in Guru Granth Sahib and in Dasam Granth as non-true man made ideas, so from that it can be concluded that Sikhism does not believe in the existence of heaven and hell; however, heaven and hell are created to temporarily reward and punish, and one will then take birth again until one merges in God. According to the Sikh scriptures, the human form is the closet form to God if the Guru is read and understood,[103][104] and the best opportunity for a human being to attain salvation and merge back with God and fully understand Him. Sikh Gurus said that nothing dies, nothing is born, everything is ever present, and it just changes forms. Like standing in front of a wardrobe, you pick up a dress and wear it and then you discard it. You wear another one. Thus, in the view of Sikhism, your soul is never born and never dies. Your soul is a part of God and hence lives forever.[105]

Confucius did not directly discuss the afterlife. Nonetheless, Chinese folk religion has had a strong influence on Confucianism, so adherents believe that their ancestors become deified spirits after death.[106] Ancestor veneration in China is widespread.

In Gnostic teachings humans contain a divine spark within them said to have been trapped in their bodies by the creator of the material universe known as the Demiurge. It was believed that this spark could be released from the material world and enter into the heavenly spiritual world beyond it if special knowledge or gnosis was attained.[107] The Cathars, for example, viewed reincarnation as a trap made by Satan, who tricked angels from the heavenly realm into entering the physical bodies of humans. They viewed the purpose of life as a way to escape the constant cycle of spiritual incarnations by letting go of worldly attachments.[108]

It is common for families to participate in ceremonies for children at a shrine, yet have a Buddhist funeral at the time of death. In old Japanese legends, it is often claimed that the dead go to a place called yomi (黄泉), a gloomy underground realm with a river separating the living from the dead mentioned in the legend of Izanami and Izanagi. This yomi very closely resembles the Greek Hades; however, later myths include notions of resurrection and even Elysium-like descriptions such as in the legend of Ōkuninushi and Susanoo. Shinto tends to hold negative views on death and corpses as a source of pollution called kegare. However, death is also viewed as a path towards apotheosis in Shintoism as can be evidenced by how legendary individuals become enshrined after death. Perhaps the most famous would be Emperor Ōjin who was enshrined as Hachiman the God of War after his death.[109]

According to Edgar Cayce, the afterlife consisted of nine realms equated with the nine planets of astrology. The first, symbolized by Saturn, was a level for the purification of the souls. The second, Mercury's realm, gives us the ability to consider problems as a whole. The third of the nine soul realms is ruled by Earth and is associated with the Earthly pleasures. The fourth realm is where we find out about love and is ruled by Venus. The fifth realm is where we meet our limitations and is ruled by Mars. The sixth realm is ruled by Neptune, and is where we begin to use our creative powers and free ourselves from the material world. The seventh realm is symbolized by Jupiter, which strengthens the soul's ability to depict situations, to analyze people and places, things, and conditions. The eighth afterlife realm is ruled by Uranus and develops psychic ability. The ninth afterlife realm is symbolized by Pluto, the astrological realm of the unconscious. This afterlife realm is a transient place where souls can choose to travel to other realms or other solar systems, it is the soul's liberation into eternity, and is the realm that opens the doorway from our solar system into the cosmos point of view.[110]

Mainstream Spiritualists postulate a series of seven realms that are not unlike Edgar Cayce's nine realms ruled by the planets. As it evolves, the soul moves higher and higher until it reaches the ultimate realm of spiritual oneness. The first realm, equated with hell, is the place where troubled souls spend a long time before they are compelled to move up to the next level. The second realm, where most souls move directly, is thought of as an intermediate transition between the lower planes of life and hell and the higher perfect realms of the universe. The third level is for those who have worked with their karmic inheritance. The fourth level is that from which evolved souls teach and direct those on Earth. The fifth level is where the soul leaves human consciousness behind. At the sixth plane, the soul is finally aligned with the cosmic consciousness and has no sense of separateness or individuality. Finally, the seventh level, the goal of each soul, is where the soul transcends its own sense of "soulfulness" and reunites with the World Soul and the universe.[110]

Taoism views life as an illusion and death as a transformation into immortality. Taoists believe that immortality of the soul can be achieved by living a virtuous life in harmony with the Tao. They are taught not to fear death, as it is simply part of nature.[111]

Traditional African religions are diverse in their beliefs in an afterlife. Hunter-gatherer societies such as the Hadza have no particular belief in an afterlife, and the death of an individual is a straightforward end to their existence.[112] Ancestor cults are found throughout Sub-Saharan Africa, including cultures like the Yombe,[113] Beng,[114] Yoruba and Ewe, "[T]he belief that the dead come back into life and are reborn into their families is given concrete expression in the personal names that are given to children....What is reincarnated are some of the dominant characteristics of the ancestor and not his soul. For each soul remains distinct and each birth represents a new soul."[115] The Yoruba, Dogon and LoDagoa have eschatological ideas similar to Abrahamic religions, "but in most African societies, there is a marked absence of such clear-cut notions of heaven and hell, although there are notions of God judging the soul after death."[115] In some societies like the Mende, multiple beliefs coexist. The Mende believe that people die twice: once during the process of joining the secret society, and again during biological death after which they become ancestors. However, some Mende also believe that after people are created by God they live ten consecutive lives, each in progressively descending worlds.[116] One cross-cultural theme is that the ancestors are part of the world of the living, interacting with it regularly.[117][118][119]

Some Unitarian Universalists believe in universalism: that all souls will ultimately be saved and that there are no torments of hell.[120] Unitarian Universalists differ widely in their theology hence there is no exact same stance on the issue.[121] Although Unitarians historically believed in a literal hell, and Universalists historically believed that everyone goes to heaven, modern Unitarian Universalists can be categorized into those believing in a heaven, reincarnation and oblivion. Most Unitarian Universalists believe that heaven and hell are symbolic places of consciousness and the faith is largely focused on the worldly life rather than any possible afterlife.[122]

The Wiccan afterlife is most commonly described as The Summerland. Here, souls rest, recuperate from life, and reflect on the experiences they had during their lives. After a period of rest, the souls are reincarnated, and the memory of their previous lives is erased. Many Wiccans see The Summerland as a place to reflect on their life actions. It is not a place of reward, but rather the end of a life journey at an end point of incarnations.[123]

Zoroastrianism states that the urvan, the disembodied spirit, lingers on earth for three days before departing downward to the kingdom of the dead that is ruled by Yima. For the three days that it rests on Earth, righteous souls sit at the head of their body, chanting the Ustavaiti Gathas with joy, while a wicked person sits at the feet of the corpse, wails and recites the Yasna. Zoroastrianism states that for the righteous souls, a beautiful maiden, which is the personification of the soul's good thoughts, words and deeds, appears. For a wicked person, a very old, ugly, naked hag appears. After three nights, the soul of the wicked is taken by the demon Vizaresa (Vīzarəša), to Chinvat bridge, and is made to go to darkness (hell).

Yima is believed to have been the first king on earth to rule, as well as the first man to die. Inside of Yima's realm, the spirits live a shadowy existence, and are dependent on their own descendants which are still living on Earth. Their descendants are to satisfy their hunger and clothe them, through rituals done on earth.

Rituals which are done on the first three days are vital and important, as they protect the soul from evil powers and give it strength to reach the underworld. After three days, the soul crosses Chinvat bridge which is the Final Judgment of the soul. Rashnu and Sraosha are present at the final judgment. The list is expanded sometimes, and include Vahman and Ormazd. Rashnu is the yazata who holds the scales of justice. If the good deeds of the person outweigh the bad, the soul is worthy of paradise. If the bad deeds outweigh the good, the bridge narrows down to the width of a blade-edge, and a horrid hag pulls the soul in her arms, and takes it down to hell with her.

Misvan Gatu is the "place of the mixed ones" where the souls lead a gray existence, lacking both joy and sorrow. A soul goes here if his/her good deeds and bad deeds are equal, and Rashnu's scale is equal.

The Society for Psychical Research was founded in 1882 with the express intention of investigating phenomena relating to Spiritualism and the afterlife. Its members continue to conduct scientific research on the paranormal to this day. Some of the earliest attempts to apply scientific methods to the study of phenomena relating to an afterlife were conducted by this organization. Its earliest members included noted scientists like William Crookes, and philosophers such as Henry Sidgwick and William James.[citation needed]

Parapsychological investigation of the afterlife includes the study of haunting, apparitions of the deceased, instrumental trans-communication, electronic voice phenomena, and mediumship.[124]

A study conducted in 1901 by physician Duncan MacDougall sought to measure the weight lost by a human when the soul "departed the body" upon death.[125] MacDougall weighed dying patients in an attempt to prove that the soul was material, tangible and thus measurable. Although MacDougall's results varied considerably from "21 grams", for some people this figure has become synonymous with the measure of a soul's mass.[126] The title of the 2003 movie 21 Grams is a reference to MacDougall's findings. His results have never been reproduced, and are generally regarded either as meaningless or considered to have had little if any scientific merit.[127]

Frank Tipler has argued that physics can explain immortality, although such arguments are not falsifiable and, in Karl Popper's views, they do not qualify as science.[128]

After 25 years of parapsychological research Susan Blackmore came to the conclusion that, according to her experiences, there is not enough empirical evidence for many of these cases.[129][130]

Mediums purportedly act as a vessel for communications from spirits in other realms. Mediumship is not specific to one culture or religion; it can be identified in several belief systems, most notably Spiritualism. While the practice gained popularity in Europe and North America in the 19th century, evidence of mediumship dates back thousands of years in Asia.[131][132][133] Mediums who claim to have contact with deceased people include Tyler Henry and Pascal Voggenhuber.

Research also includes the study of the near death experience. Scientists who have worked in this area include Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, Raymond Moody, Sam Parnia, Michael Sabom, Bruce Greyson, Peter Fenwick, Jeffrey Long, Susan Blackmore, Charles Tart, William James, Ian Stevenson, Michael Persinger, Pim van Lommel, Penny Sartori, Walter van Laack among others.[134][135]

Past life regression is a method that uses hypnosis to recover what practitioners believe are memories of past lives or incarnations. The technique used during past-life regression involves the subject answering a series of questions while hypnotized to reveal identity and events of alleged past lives, a method similar to that used in recovered memory therapy and one that, similarly, often misrepresents memory as a faithful recording of previous events rather than a constructed set of recollections.

However, medical experts and practitioners do not agree that the past life memories gained from past life regressions are truly from past lives; experts generally regard claims of recovered memories of past lives as fantasies or delusions or a type of confabulation, because the use of hypnosis and suggestive questions can tend to leave the subject particularly likely to hold distorted or false memories.[136][137][138]

There is a view based on the philosophical question of personal identity, termed open individualism by Daniel Kolak, that concludes that individual conscious experience is illusory, and because consciousness continues after death in all conscious beings, you do not die. This position has allegedly been supported by physicists such as Erwin Schrödinger and Freeman Dyson.[139]

Certain problems arise with the idea of a particular person continuing after death. Peter van Inwagen, in his argument regarding resurrection, notes that the materialist must have some sort of physical continuity.[140] John Hick also raises questions regarding personal identity in his book, Death and Eternal Life, using an example of a person ceasing to exist in one place while an exact replica appears in another. If the replica had all the same experiences, traits, and physical appearances of the first person, we would all attribute the same identity to the second, according to Hick.[141]

In the panentheistic model of process philosophy and theology the writers Alfred North Whitehead and Charles Hartshorne rejected the idea that the universe was made of substance, instead saying reality is composed of living experiences (occasions of experience). According to Hartshorne people do not experience subjective (or personal) immortality in the afterlife, but they do have objective immortality because their experiences live on forever in God, who contains all that was. However other process philosophers such as David Ray Griffin have written that people may have subjective experience after death.[142][143][144][145]

Psychological proposals for the origin of a belief in an afterlife include cognitive disposition, cultural learning, and as an intuitive religious idea.[146]

In 2008, a large-scale study conducted by the University of Southampton involving 2,060 patients from 15 hospitals in the United Kingdom, United States and Austria was launched. The AWARE (AWAreness during REsuscitation) study examined the broad range of mental experiences in relation to death. In a large study, researchers also tested the validity of conscious experiences for the first time using objective markers, to determine whether claims of awareness compatible with out-of-body experiences correspond with real or hallucinatory events.[147] The results revealed that 40% of those who survived a cardiac arrest were aware during the time that they were clinically dead and before their hearts were restarted. One patient also had a verified out-of-body experience (over 80% of patients did not survive their cardiac arrest or were too sick to be interviewed), but his cardiac arrest occurred in a room without markers. Dr. Parnia in the interview stated, "The evidence thus far suggests that in the first few minutes after death, consciousness is not annihilated."[148] The AWARE study drew the following primary conclusions:

- In some cases of cardiac arrest, memories of visual awareness compatible with so called out-of-body experiences may correspond with actual events.

- A number of NDErs may have vivid death experiences, but do not recall them due to the effects of brain injury or sedative drugs on memory circuits.

- The recalled experience surrounding death merits a genuine investigation without prejudice.[149]

Studies have also been done on the widely reported phenomenon of near death experiences (NDE). Experiencers commonly report being transported to a different "realm" or "plane of existence" and they have been shown to display a lasting positive aftereffect on most experiencers.[150]

Under the theoretical framework of extended cognition, an organism's cognitive processes may exist beyond the physical body and persist even after death.[151]

- Allegory of the long spoons

- Astral plane

- Bardo

- Brig of Dread (Bridge of Dread)

- Empiricism

- Epistemology

- Eternal oblivion

- Exaltation (Mormonism)

- Fate of the unlearned

- Heaven

- Rebecca Hensler

- Hell

- Immortality

- Mictlan

- Mind uploading

- Nirvana

- Omega Point

- Paradise

- Phowa

- Pre-existence

- Purgatory

- Rebirth

- Reincarnation

- Soul

- Soul flight

- Soul retrieval

- Spiritism

- Suspended animation

- Spirit World

- Undead

- Underworld

- ^ some of the verses are:

- "... but compared with the Hereafter the life of this world is but a [trifling] enjoyment" [Quran 13:26]

- " ...The life of this world is nothing but the wares of delusion." [Quran 3:185–186]

- " ...Know that the life of this world is mere diversion and play, glamour and mutual vainglory among you and rivalry for wealth and children" (Q.57:20)[Quran 57:20]

- " ...Seek the abode of the Hereafter by means of what Allah has given you, while not forgetting your share of this world. [Quran 28:77]

- ^ The Last Day has a number of other names. It is also called the Encompassing Day (al-yawm al-muḥīṭ), more commonly known as the "Day of Resurrection" (yawm al-qiyāma), "Day of Judgment" (yawm ad-dīn), and "Day of Reckoning" (yawm al-ḥisāb), as well as both the "Day of Separation" (yawm al-faṣl) and "Day of Gathering" (yawm al-jamʿ), and is also referred to as as-Sāʿah, meaning "the Hour" signaled by the blowing of the horn/trumpet.[71]

- ^ "I have created the jinn and humankind only for My worship."[ 51:56]

- ^ "One should note there was a near consensus among Muslim theologians of the later periods that punishment for Muslim grave sinners would only be temporary; eventually after a purgatory sojourn in hell's top layer they would be admitted into paradise."[85] Prior to that, theologians of the Kharijite and Mu'tazilite schools insisted that the "sinful" and "unrepentant" should be punished even if they were believers, but this position has been "lastingly defeated and erased" by mainstream Islam.[86]

- ^ Microsoft News. Near-death experience expert says he’s proven there is an afterlife ‘without a doubt’. Retrieved 1 Sept., 2023

- ^ Aiken, Lewis R. (2000). Dying, death, and bereavement (4th ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0-585-30171-9. OCLC 45729833.

- ^ Rita M. Gross (1993). Buddhism After Patriarchy: A Feminist History, Analysis, and Reconstruction of Buddhism. State University of New York Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-4384-0513-1.

- ^ Anakwue, Nicholas Chukwudike (22 February 2018). "The African Origins of Greek Philosophy: Ancient Egypt in Retrospect". Phronimon. 18: 167–180. doi:10.25159/2413-3086/2361. ISSN 2413-3086.

- ^ McClelland, Norman (2018). Encyclopedia of Reincarnation and Karma. McFarland. pp. 1–320. ISBN 978-0786456758.

- ^ see Charles Taliaferro, Paul Draper, Philip L. Quinn, A Companion to Philosophy of Religion. John Wiley and Sons, 2010, p. 640, Google Books For Plato, see Kamtekar 2016 and Campbell 2022. Kamtekar, Rachana. "The Soul's (After-) Life," Ancient Philosophy 36 (2016): 1–18. Campbell, Douglas R. "Plato's Theory of Reincarnation: Eschatology and Natural Philosophy," Review of Metaphysics 75 4 (2022): 643–665.

- ^ Gananath Obeyesekere, Imagining Karma: Ethical Transformation in Amerindian, Buddhist, and Greek Rebirth. University of California Press, 2002, p. 15.

- ^ Hitti, Philip K (2007) [1924]. Origins of the Druze People and Religion, with Extracts from their Sacred Writings (New Edition). Columbia University Oriental Studies. 28. London: Saqi. pp. 13–14. ISBN 0-86356-690-1

- ^ a b Heindel, Max (1985) [1939, 1908] The Rosicrucian Christianity Lectures (Collected Works): The Riddle of Life and Death Archived 29 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Oceanside, California. 4th edition. ISBN 0-911274-84-7

- ^ An important recent work discussing the mutual influence of ancient Greek and Indian philosophy regarding these matters is The Shape of Ancient Thought by Thomas McEvilley.

- ^ Max Heindel, Death and Life in Purgatory Archived 11 July 2006 at the Wayback Machine—Life and Activity in Heaven Archived 11 July 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Life After Death Revealed – What Really Happens in the Afterlife". Spiritual Science Research Foundation. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ^ Somov, Alexey (2018). "Afterlife". In Hunter, David G.; van Geest, Paul J. J.; Lietaert Peerbolte, Bert Jan (eds.). Brill Encyclopedia of Early Christianity Online. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. doi:10.1163/2589-7993_EECO_SIM_00000067. ISSN 2589-7993.

- ^ Richard P. Taylor, Death and the afterlife: A Cultural Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, 2000, ISBN 0-87436-939-8

- ^ Bard, Katheryn (1999). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. Routledge.

- ^ Kathryn Demeritt, Ptah's Travels: Kingdoms of Ancient Egypt, 2005, p. 82

- ^ Shushan, Gregory (2011). Conceptions of the Afterlife in Early Civilizations: Universalism, Constructivism and Near-Death Experience. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. p. 53. ISBN 9781441130884.

- ^ Glennys Howarth, Oliver Leaman, Encyclopedia of death and dying, 2001, p. 238

- ^ Natalie Lunis, Tut's Deadly Tomb, 2010, p. 11

- ^ Fergus Fleming, Alan Lothian, Ancient Egypt's Myths and Beliefs, 2011, p. 96

- ^ "Door to Afterlife found in Egyptian tomb". meeja.com.au. 30 March 2010. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 30 September 2008.

- ^ F. P. Retief and L. Cilliers, "Burial customs, the afterlife and the pollution of death in ancient Greece", Acta Theologica 26(2), 2006, p. 45 (PDF Archived 6 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine).

- ^ Social Studies School Service, Ancient Greece, 2003, pp. 49–51

- ^ Perry L. Westmoreland, Ancient Greek Beliefs, 2007, pp. 68–70

- ^ N. Sabir, Heaven Hell Or, 2010, p. 147

- ^ See Timaeus 90–92. For a recent scholarly treatment, see Douglas R. Campbell, "Plato's Theory of Reincarnation: Eschatology and Natural Philosophy," Review of Metaphysics 75 (4): 643–665. 2022.

- ^ "Norse Mythology | The Nine Worlds". www.viking-mythology.com. Archived from the original on 15 May 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ^ "Fólkvangr, Freyja welcomes you to the Field of the Host". Spangenhelm. 20 May 2016. Archived from the original on 15 September 2017. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ^ "SHEOL - JewishEncyclopedia.com". www.jewishencyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 18 September 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- ^ Berdichevsky 2016, p. 22.

- ^ a b Pearson, Fred (1938). "Sheol and Hades in Old and New Testament". Review & Expositor. 35 (3): 304–314. doi:10.1177/003463733803500304. S2CID 147690674 – via SAGE journals.

- ^ Berdichevsky, Norman (2016). Modern Hebrew: The Past and Future of a Revitalized Language. McFarland. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-4766-2629-1.

- ^ "Tractate Sanhedrin: Interpolated Section: Those Who have no Share in the World to Come". Sacred-texts.com. Archived from the original on 20 October 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- ^ "Jehoiakim". Jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Archived from the original on 9 November 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- ^ Maimonides' Introduction to Perek Helek, publ. and transl. by Maimonides Heritage Center, p. 22-23.

- ^ Paull Raphael, Simcha (2019). Jewish Views of the Afterlife. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 177–180. ISBN 9781538103463.

- ^ "soc.culture.jewish FAQ: Jewish Thought (6/12) Section – Question 12.8: What do Jews say happens when a person dies? Do Jews believe in reincarnation? In hell or heaven? Purgatory?". Faqs.org. 8 August 2012. Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- ^ Saadia Gaon in Emunoth ve-Deoth Section vi

- ^ a b Reincarnation in the Jewish Tradition on YouTube

- ^ "Ask the Rabbi – Reincarnation". Judaism.about.com. 17 December 2009. Archived from the original on 9 March 2014. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- ^ Yirmiyahu, Rabbi (12 July 2003). "Reincarnation " Ask! " Ohr Somayach". Ohr.edu. Archived from the original on 9 March 2014. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- ^ Martin Buber, "Legende des Baalschem" in Die Chassidischen Bücher, Hellerau 1928, especially Die niedergestiegene Seele

- ^ "Reincarnation and the Holocaust FAQ". Archived from the original on 16 July 2011.

- ^ "Where does the soul go? New course explores spiritual existence". Middletown, CT. West Hartford News. 14 October 2015. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ^ "Matthew 22:23–33". Biblegateway.com. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- ^ a b Boulaouali, Tijani (3 November 2022). "Biblical Eschatology and Qur'anic 'Ākhirāh: A Comparative Approach of the Concepts Afterlife, Death and the Day of Judgement". Khazanah Theologia. 4 (3): 147–158. doi:10.15575/kt.v4i3.19851. ISSN 2715-9701. S2CID 255287161. Archived from the original on 8 January 2023. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- ^ John 5:24"The New American Bible". Vatican.va. Archived from the original on 2 August 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- ^ Fosdick, Harry Emerson. A guide to understanding the Bible. New York: Harper & Brothers. 1956. p. 276.

- ^ Acts of Paul and Thecla Archived 6 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine 8:5

- ^ He wrote that a person "may afterward in a quite different manner be very much interested in what is better, when, after his departure out of the body, he gains knowledge of the difference between virtue and vice and finds that he is not able to partake of divinity until he has been purged of the filthy contagion in his soul by the purifying fire" (emphasis added)—Sermon on the Dead, AD 382, quoted in The Roots of Purgatory Archived 27 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "purgatory" Archived 17 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine. The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. Columbia University Press., 2003. Answers.com 6 June 2007.

- ^ "Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary". Perseus.tufts.edu. Archived from the original on 21 February 2008. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- ^ a b Swedenborg, E. (2000). "Heaven and Hell". Swedenborg Foundation. Archived from the original on 8 December 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ "limbo – definition of limbo by the Free Online Dictionary, Thesaurus and Encyclopedia". Thefreedictionary.com. Archived from the original on 15 May 2020. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- ^ Ted Campbell, Methodist Doctrine: The Essentials (Abingdon 1999), quoted in Feature article by United Methodist Reporter Managing Editor Robin Russell Archived 22 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine and in FAQ Belief: What happens immediately after a person dies? Archived 13 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Andrew P. Klager, "Orthodox Eschatology and St. Gregory of Nyssa's De vita Moysis: Transfiguration, Cosmic Unity, and Compassion," In Compassionate Eschatology: The Future as Friend, eds. Ted Grimsrud & Michael Hardin, 230–52 (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2011), 245" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 March 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ^ St. Isaac the Syrian, "Homily 28," In The Ascetical Homilies of Saint Isaac the Syrian, trans. Dana Miller (Brookline, MA: Holy Transfiguration Monastery Press, 1984), 141.

- ^ Fr. Thomas Hopko, "Foreword," in The Orthodox Church, Sergius Bulgakov (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, 1988), xiii.

- ^ "Andrew P. Klager, "Orthodox Eschatology and St. Gregory of Nyssa's De vita Moysis: Transfiguration, Cosmic Unity, and Compassion," In Compassionate Eschatology: The Future as Friend, eds. Ted Grimsrud & Michael Hardin, 230–52 (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2011), 251" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 March 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ^ Kallistos Ware, The Orthodox Church (New York: Penguin, 1997), 262.

- ^ Paulsen, David L.; Cook, Roger D.; Christensen, Kendel J. (2010). "The Harrowing of Hell: Salvation for the Dead in Early Christianity". Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture. 19 (1): 56–77. doi:10.5406/jbookmormotheres.19.1.0056. ISSN 1948-7487. JSTOR 10.5406/jbookmormotheres.19.1.0056. S2CID 171733241. Archived from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ "Doctrine and Covenants, Section 76". Archived from the original on 13 July 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- ^ Spencer W. Kimball: The Miracle of Forgiveness, p. 123.