====

두 문화

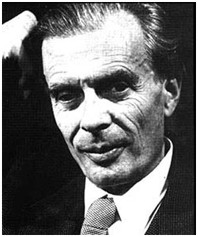

두 문화는 영국의 과학자 겸 소설가 찰스 퍼시 스노우가 행한 영향력 있는 1959년 리드 강좌(Rede Lecture)의 제목이다. 그 주제는 현대 사회의 두 문화 곧 과학과 인문학 사이의 의사소통 단절이 세계 문제를 해결하는 데 가장 큰 걸림돌이라는 것이었다. 스노우는 교육받은 과학자이면서 성공적인 소설가로서 그 문제의 거론에 알맞은 자격이 있었다.

그 강좌는 5월 7일 케임브리지 대학교 본부 세니트 하우스에서 열렸고, 이내 《두 문화와 과학 혁명》으로 출판되었다. 그 강좌와 책은 스노우가 역시 "두 문화"라는 제목으로 1956년 10월 6일에 출판된 《뉴 스테이츠맨》 잡지에 실은 논문을 확장한 것이었다. 스노우의 강좌가 책으로 출판되자 대서양 양쪽에서 널리 읽히고 토론되었으며, 그는 마침내 《두 문화와 두 번째 시각: 두 문화와 과학 혁명의 확장판》(1964)을 또 다시 쓰게 되었다.

그러나 스노우의 주장에 대한 비판이 없지 않았다. 예컨대, 문학평론가 프랭크 리비스는 《더 스펙테이터》에서 스노우를 조롱하고 그를 과학계의 PR 맨이라고 깎아내렸다. 그러나 《더 타임스 리터러리 서플먼트》는 《두 문화와 과학 혁명》을 2차 대전 이후 서방세계의 대중적 담론에 영향을 미친 백 권의 책에 포함시켰다.[1]

함축과 영향[편집]

"두 문화"는 두 입장 차이를 나타내는 간편한 표현으로서 보편적인 어휘에 포함되었다. 그 두 입장이란:

- 과학적 방법은 언어와 문화 속에 뿌리박혀 있다는 관점으로 인문학을 뒤덮고 더욱 더 구성주의적으로 가는 세계관, 그리고

- 관찰자는 편견없이 문화와 상관없이 객관적으로 자연을 관찰할 수 있다고 보는 과학적 관점.

- 그 표현은 현대 세계의 과학자와 인문학 지식인들 사이에서 벌어져 온 균열 또는 적대감이 감도는 몰이해를 나타내는, 애매하면서도 널리 퍼진 약호로서 살아 남았다.[2]

두 입장의 이같은 양극화는 정말 20세기 후반 학계의 한 쟁점이었다. 스노우의 원래 주장은 수사학적 도구에 의존했다.

- 그의 골-간격-균열 주장을 더욱 강조하기 위해서, 스노우는 이내 "인문학 지식인"과 "전통 문화"를 호환적으로 사용한다. 이같은 혼동은 "모든 '전통적' 문화"에 "비과학적" 심지어 "반과학적" 경향이 있다는 관념을 불러일으킨다. 이것은 무엇을 뜻하는가? 아리스토텔레스, 유클리드, 갈릴레오, 코페르니쿠스, 데카르트, 보일, 뉴톤, 로크, 칸트: "모든 '전통적' 문화" 속에서 이들보다 더 "전통적"인 사람이 있는가[?][2]

스노우 자신도 다시 생각해보고 2분법적 단정에서 약간 후퇴했다. 그의 1963년 책에서 그는 '제3 문화'의 중재 가능성에 대하여 좀 더 낙관적으로 말했다. 이 개념은 나중에 존 브록맨이 1995년 책 《제3 문화: 과학 혁명을 넘어서》에서 다시 꺼냈다. 스테판 콜리니( Stefan Collini)는 《두 문화》(1993)를 다시 인쇄할 때, 세월이 스노우가 주목했던 문화의 간격을 많이 줄였지만 모두 없애지는 못했다고 지적했다.

- 여러 학문 분야의 특성과 각 분야마다의 발달에 대한 이해가 더해갈수록 '두 문화' 같은 단순한 2분법은 전보다 덜 그럴듯하게 들리게 되었다.[3]

스티븐 제이 굴드의 2003년 책 《고슴도치, 여우, 그리고 훈장님의 발진》은 다른 시각을 제시한다. 그 책은 변증법적 해석을 내세워, "두 문화"라고 하는 스노우의 개념은 과녁을 빗나갔을 뿐만 아니라 근시안적이고 해로운 시각이며, 아마 수십 년간 필요없는 담 쌓기로 이어졌을 것이라고 주장한다.

그럼에도 불구하고, 스노우의 기본 시각은 아직도 유효한 바: 인문학자들은 과학을 많이 알지 못하고 열역학 제2법칙을 몰라도 아무렇지도 않은 한편, 과학자는 세익스피어가 누구인지도 모르고 정말이지 그의 연극을 많이 알지 못해도 아무렇지도 않다. 이같은 간격은 "두 문화"라는 간략한 기호로 이해될 수 있으며, 이것은 스노우 경 덕택이다.

철학적 화신[편집]

사이먼 크리칠리는 《대륙 철학: 짧은 개요》(2001, p. 49)에서 스노우의 강좌에 대하여 다음과 같이 시사했다:

- [스노우]는 공동의 문화는 사라지고 두 다른 문화 곧 한편으로 과학자들이 대표하는 문화와 다른 한편 스노우가 말하는 "인문학 지식인들"이 대표하는 문화가 대두했다고 진단했다. 만일 전자가 과학과 기술과 산업에 의한 사회 개혁과 진보를 선호한다면, 인문학 지식인들은 고도 산업 사회에 대한 이해와 동조의 관점에서 스노우가 말하는 '자연 상태의 러다이트들'이다. 밀의 용어로는, 그 분파는 벤덤 파와 콜러리지 파의 사이다.

다시 말해서, 스노우가 말한 바는 19세기 중엽에 유행했던 논쟁을 다시 표면화시킨 것이라고 크리칠리는 지적했다. 크리칠리는 리비스가 논쟁에 기여한 바는 '악의에 찬 인신공격'이었고, 나아가 토머스 헨리 헉슬리와 매슈 아널드를 또한 인용하면서 그 논쟁은 '영국 문화사에서 잘 알려진 충돌'(ibid, p. 51)이라고 지적했다.

스노우 인용[편집]

- 1930년대 어느 날 고드프리 하디가 나에게 이렇게 말해서 좀 놀란 적이 있었다:

- 전통 문화의 기준에 비추어 고등교육을 받았다고 여겨지고 과학자들의 무식함에 대하여 신이 나서 유감을 표명하는 사람들의 모임에 나는 여러 번 참석했다. 한두 차례 당하고 나서, 나는 그들 중 얼마나 많은 사람이 열역학 제2법칙을 설명할 수 있느냐고 물었다. 반응은 싸늘했고 또 부정적이었다. 그때 나는 "당신은 세익스피어의 이 작품을 읽었습니까?"에 해당하는 과학자 입장의 질문을 던졌을 뿐이었다.

- 만일 내가 보다 더 쉬운 질문, 예컨대, "당신은 읽을 수 있습니까?"에 해당하는 질문, "당신에게 질량 또는 가속도는 무슨 뜻입니까?"라고 물었다면, 고등교육을 받은 열 사람 가운데 불과 한 사람이 내가 자기와 같은 언어를 쓰고 있다고 여겼을 것이라고 이제 나는 믿는다. 현대과학의 거대한 건축물이 이렇게 높아지는데, 서양에서 가장 머리좋은 사람들의 대부분은 그것을 꿰뚫어 보는 통찰력이 구석기 선조들의 수준이다.

- 기술은 [...] 요물이다. 그것은 한편 당신에게 선물을 주고, 다른 한편 당신의 등을 찌른다.

각주[편집]

- ↑ The hundred most influential books since the war TLS

- ↑ 가 나 Roger Kimball: “The Two Cultures” today, on the C. P. Snow–F. R. Leavis controversy. In: The New Criterion, Volume 12, February 1994.

- ↑ Stefan Collini, p. xxxv of his introduction to the 1993 The Two Cultures, uses very similar terms.

같이 보기[편집]

- 문화 전쟁 (Culture war)

- 과학 전쟁 (Science wars)

- 올더스 헉슬리

- 통섭

- 고슴도치, 여우, 그리고 훈장님의 발진 (The Hedgehog, the Fox, and the Magister's Pox)

- 라이만 브릭스 칼리지 (Lyman Briggs College)

- 루이스 멈퍼드

- 제럴드 허드 (Gerald Heard)

- 에지 재단 (Edge Foundation)

- 지식 체계 나무 (Tree of Knowledge System)

외부 링크[편집]

====

The Two Cultures

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to navigationJump to search

First edition (publ. OUP)

"The Two Cultures" is the first part of an influential 1959 Rede Lecture by British scientist and novelist C. P. Snow which were published in book form as The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution the same year.[1][2] Its thesis was that science and the humanities which represented "the intellectual life of the whole of western society" had become split into "two cultures" and that this division was a major handicap to both in solving the world's problems.

Contents

1The lecture

2Implications and influence

3Antecedents

4See also

5References

6Further reading

7External links

The lecture[edit]

The talk was delivered 7 May 1959 in the Senate House, Cambridge, and subsequently published as The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution. The lecture and book expanded upon an article by Snow published in the New Statesman of 6 October 1956, also entitled "The Two Cultures".[3] Published in book form, Snow's lecture was widely read and discussed on both sides of the Atlantic, leading him to write a 1963 follow-up, The Two Cultures: And a Second Look: An Expanded Version of The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution.[4]

Snow's position can be summed up by an often-repeated part of the essay:

A good many times I have been present at gatherings of people who, by the standards of the traditional culture, are thought highly educated and who have with considerable gusto been expressing their incredulity at the illiteracy of scientists. Once or twice I have been provoked and have asked the company how many of them could describe the Second Law of Thermodynamics. The response was cold: it was also negative. Yet I was asking something which is the scientific equivalent of: Have you read a work of Shakespeare's?[5] I now believe that if I had asked an even simpler question – such as, What do you mean by mass, or acceleration, which is the scientific equivalent of saying, Can you read? – not more than one in ten of the highly educated would have felt that I was speaking the same language. So the great edifice of modern physics goes up, and the majority of the cleverest people in the western world have about as much insight into it as their neolithic ancestors would have had.[5]

In 2008, The Times Literary Supplement included The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution in its list of the 100 books that most influenced Western public discourse since the Second World War.[2]

Snow's Rede Lecture condemned the British educational system as having, since the Victorian era, over-rewarded the humanities (especially Latin and Greek) at the expense of scientific and engineering education, despite such achievements having been so decisive in winning the Second World War for the Allies.[6] This in practice deprived British elites (in politics, administration, and industry) of adequate preparation to manage the modern scientific world. By contrast, Snow said, German and American schools sought to prepare their citizens equally in the sciences and humanities, and better scientific teaching enabled these countries' rulers to compete more effectively in a scientific age. Later discussion of The Two Cultures tended to obscure Snow's initial focus on differences between British systems (of both schooling and social class) and those of competing countries.[6]

Implications and influence[edit]

The literary critic F. R. Leavis called Snow a "public relations man" for the scientific establishment in his essay Two Cultures?: The Significance of C. P. Snow, published in The Spectator in 1962. The article attracted a great deal of negative correspondence in the magazine's letters pages.[7]

In his 1963 book Snow appeared to revise his thinking and was more optimistic about the potential of a mediating third culture. This concept was later picked up in John Brockman's The Third Culture: Beyond the Scientific Revolution. Introducing a reprint of The Two Cultures, Stefan Collini has argued that the passage of time has done much to reduce the cultural divide Snow noticed, but has not removed it entirely.

Stephen Jay Gould's The Hedgehog, the Fox, and the Magister's Pox provides a different perspective. Assuming the dialectical interpretation, it argues that Snow's concept of "two cultures" is not only off the mark, it is a damaging and short-sighted viewpoint, and that it has perhaps led to decades of unnecessary fence-building.

Simon Critchley, in Continental Philosophy: A Very Short Introduction suggests:[8]

[Snow] diagnosed the loss of a common culture and the emergence of two distinct cultures: those represented by scientists on the one hand and those Snow termed 'literary intellectuals' on the other. If the former are in favour of social reform and progress through science, technology and industry, then intellectuals are what Snow terms 'natural Luddites' in their understanding of and sympathy for advanced industrial society. In Mill's terms, the division is between Benthamites and Coleridgeans.

That is, Critchley argues that what Snow said represents a resurfacing of a discussion current in the mid-nineteenth century. Critchley describes the Leavis contribution to the making of a controversy as "a vicious ad hominem attack"; going on to describe the debate as "a familiar clash in English cultural history" citing also T. H. Huxley and Matthew Arnold.[9][10]

In his opening address at the Munich Security Conference in January 2014, the Estonian president Toomas Hendrik Ilves said that the current problems related to security and freedom in cyberspace are the culmination of absence of dialogue between "the two cultures": "Today, bereft of understanding of fundamental issues and writings in the development of liberal democracy, computer geeks devise ever better ways to track people... simply because they can and it's cool. Humanists on the other hand do not understand the underlying technology and are convinced, for example, that tracking meta-data means the government reads their emails."[11]

Antecedents[edit]

Contrasting scientific and humanistic knowledge is a repetition of the Methodenstreit of 1890 German universities.[12] A quarrel in 1911 between Benedetto Croce and Giovanni Gentile on the one hand and Federigo Enriques on the other one is believed to have had enduring effects in the separation of the two cultures in Italy and to the predominance of the views of (objective) idealism over those of (logical) positivism.[13] In the social sciences it is also commonly proposed as the quarrel of positivism versus interpretivism.[12]

See also[edit]

Culture war

The Third Culture

Science wars

Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge, a 1998 book written by biologist Edward Osborne Wilson, as an attempt to bridge the gap between "the two cultures"

Quarrel of the Ancients and the Moderns

Interdisciplinarity, a movement to cross boundaries between academic disciplines, including the divide between "the two cultures"

References[edit]

- ^ Snow, Charles Percy (2001) [1959]. The Two Cultures. London: Cambridge University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-521-45730-9.

- ^ Jump up to:a b "The hundred most influential books since the war". The Times. London. 30 December 2008.

- ^ Snow 2013.

- ^ Snow, Charles Percy (1963). The Two Cultures: And a Second Look: An Expanded Version of The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Jump up to:a b "Across the Great Divide". Nature Physics. 5 (5): 309. 2009. Bibcode:2009NatPh...5..309.. doi:10.1038/nphys1258.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Jardine, Lisa (2010). "CP Snow's Two Cultures Revisited" (PDF). Christ's College Magazine: 48–57. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 April 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2012. Jardine's 2009 C. P. Snow Lecture honored the 50th anniversary of Snow's Rede Lecture. She places Snow's lecture into its historical context, and emphasizes the expansion of certain elements of the Rede Lecture in Snow's Godkin Lectures at Harvard University in 1960. These were ultimately published as Science and Government. New American Library. 1962.

- ^ Kimball, Roger (12 February 1994). "The Two Cultures' today: On the C. P. Snow–F. R. Leavis controversy". The New Criterion.

- ^ Critchley 2001, p. 49.

- ^ Critchley 2001, p. 51.

- ^ Collini 1993, p. xxxv.

- ^ Ilves, Toomas Hendrik: "Rebooting Trust? Freedom vs Security in Cyberspace Archived 23 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine" Opening address at Munich Security Conference Cyber 31 January 2014. 31.01.2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Brint, Steven G (2002), The Future of the City of Intellect: The Changing American University, pp. 212–3, ISBN 9780804745314, positivism-versus-interpretation language [...] these fractal distinctions are generally quite old. Most of them have been around at least since the celebrated Methodenstreit of the German universities in the late nineteenth century. CP Snow's "two cultures" argument captures a later instantiation of them. [...] In negotiating the complexities of social scientific and humanistic knowledge, it is extremely helpful to have a dichotomy like positivism versus interpretation, because it saves our having to remember the exact degree of positivism of any scholarly group. [...] Every single social science discipline has internal debates about positivism/interpretation, narrative/analysis, and so on. The narrative/analytic debate may look very different in economics, anthropology, and English. But underneath all the surface differences it is quite similar.

- ^ Dauben, Joseph W.; Scriba, Christoph J. (2002). Writing the History of Mathematics: Its Historical Development. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 422. ISBN 978-3-7643-6167-9.

Further reading[edit]

Burguete, Maria, and Lam, Lui, eds. (2008). Science Matters: Humanities as Complex Systems. World Scientific: Singapore. ISBN 978-981-283-593-2

James, Frank A. J. L. (29 November 2016). "Introduction: Some Significances of the Two Cultures Debate" (PDF). Interdisciplinary Science Reviews. 41 (2–3): 107–117. doi:10.1080/03080188.2016.1223651..

Andrew Sinclair, The Red and the Blue. Intelligence, Treason and the Universities (Coronet Books, Hodder and Stoughten, U.K. 1987) 211 pages ISBN 0-340-41687-4

External links[edit]

Bragg, Melvyn, The Two Cultures (discussion), UK: BBC Radio 4.

Critchley, Simon (2001), Continental Philosophy: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-285359-2.

Collini, Stefan (1993), "Introduction", in Snow, Charles Percy (ed.), The Two Cultures, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-06520-7

Ferris, Timothy (13 October 2011), "The World of the Intellectual vs. The World of the Engineer", Wired.

Griffiths, Phillip (13 September 1995), 'Two Cultures' Today, UK: St Andrews.

Precht, Richard David (2013), "Natural Sciences and Humanities: Genesis of two Worlds", ZAKlessons (Webvideo), Google You tube.

Snow, Charles Percy (January 2013), "The Two Cultures", The New Statesman.

Snow, Charles Percy (1959), "The Two Cultures (The Rede Lecture)".

"Are We Beyond the Two Cultures?", Seed, 7 May 2009, archived from the original on 10 May 2009.