David Abram

David Abram | |

|---|---|

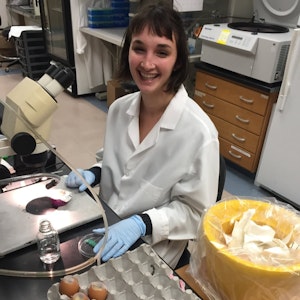

Abram in 2018 | |

| Born | June 24, 1957 Baldwin, Nassau County, New York, U.S. |

| Education | Wesleyan University Yale School of Forestry State University of New York at Stony Brook (BA, MA, PhD) |

| Era | 20th-/21st-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | |

| Institutions | University of California, Berkeley |

Notable ideas |

|

David Abram (born June 24, 1957) is an American ecologist and philosopher best known for his work bridging the philosophical tradition of phenomenology with environmental and ecological issues.[1][2] He is the author of Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology[3] (2010) and The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-than-Human World (1996), for which he received the Lannan Literary Award for Nonfiction.[4] Abram is founder and creative director of the Alliance for Wild Ethics (AWE);[5] his essays on the cultural causes and consequences of ecological disarray have appeared often in such journals as the online magazine Emergence, Orion, Environmental Ethics, Parabola, Tikkun and The Ecologist, as well as in numerous academic anthologies.[6]

In 1996 Abram coined the phrase "the more-than-human world" as a way of referring to earthly nature (introducing it in the subtitle of The Spell of the Sensuous and throughout the text of that book); the term was gradually adopted by other scholars, theorists, and activists, and has become a key phrase within the lingua franca of the broad ecological movement.[7] In recent writings, Abram sometimes refers to the more-than-human world as "the commonwealth of breath."[8]

Abram was the first contemporary philosopher to advocate a reappraisal of "animism" as a complexly nuanced and uniquely viable worldview — one which roots human cognition in the sensitive and sentient human body, while affirming the ongoing entanglement of our bodily experience with the uncanny sentience of other animals (each of which encounters the same world that we perceive yet from an outrageously different angle and perspective).[9] A close student of the traditional ecological knowledge systems of diverse indigenous peoples, Abram articulates the entwinement of human subjectivity not only with other animals but with the varied sensitivities of the many plants upon which humans depend, as well as our cognitive entanglement with the collective sensitivity and sentience of the particular earthly places — the bioregions (or ecosystems) — that surround and sustain our communities. In recent years his work has come to be closely associated both with the "new animism," and with a broad movement loosely termed "New Materialism," due to Abram's espousal of a radically transformed sense of matter and materiality.[10]

Life and early influences[edit]

Born in the suburbs of New York City, Abram began practicing sleight-of-hand magic during his high school years in Baldwin, Long Island; it was this craft that sparked his ongoing fascination with perception. In 1976, he began working as "house magician" at Alice's Restaurant in the Berkshires of Massachusetts and soon was performing at clubs throughout New England[11] while studying at Wesleyan University. After his second year of college, Abram took a year off to travel as an itinerant street magician through Europe and the Middle East; toward the end of that journey, in London, he began exploring the application of sleight-of-hand magic to psychotherapy under the guidance of Dr. R. D. Laing. After graduating summa cum laude from Wesleyan in 1980, Abram traveled throughout Southeast Asia as an itinerant magician, living and studying with traditional, indigenous magic practitioners (or medicine persons) in Sri Lanka, Indonesia, and Nepal. Upon returning to North America he continued performing while devoting himself to the study of natural history and ethno-ecology, visiting and learning from native communities in the Southwest desert and the Pacific Northwest. A much-reprinted essay written while studying ecology at the Yale School of Forestry in 1984 — entitled "The Perceptual Implications of Gaia"[12] — brought Abram into association with the scientists formulating the Gaia Hypothesis; he was soon lecturing in tandem with biologist Lynn Margulis and geochemist James Lovelock both in Britain and the United States. In the late 1980s, Abram turned his attention to exploring the decisive influence of language upon the human senses and upon our sensory experience of the land around us. Abram received a doctorate for this work from the State University of New York at Stony Brook, in 1993.[13]

Work[edit]

Abram's writing is informed by his studies among indigenous peoples in Indonesia, Nepal, and the Americas, as well as by the American nature-writing tradition that stems from Henry David Thoreau, Walt Whitman, and Mary Austin. His philosophical work is informed by the European tradition of phenomenology — especially by the writings of the French phenomenologist, Maurice Merleau-Ponty. Abram's evolving work has also been influenced by his friendships with the archetypal psychologist James Hillman, the iconoclastic evolutionary biologist Lynn Margulis, and the social critic and radical historian Ivan Illich — as well as by his esteem for the American poet Gary Snyder and the agrarian novelist, poet, and essayist Wendell Berry.[5]

Writing in the mid-nineteen nineties, and finding himself frustrated by the problematic terminology of environmentalism (dismayed by the longstanding conceptual gulf between humankind and the rest of nature tacitly implied by the use of conventional terms like "environment" and even by the word "nature" itself, which is so often contrasted with "culture" as though there were a neat divide between the two), Abram coined the phrase "the more-than-human world" in order to signify the broad commonwealth of earthly life, a realm that manifestly includes humankind and its culture, but which also necessarily exceeds human culture. The phrase was intended, first and foremost, to indicate that the space of human culture was a subset within a larger set — that the human world was necessarily sustained, surrounded, and permeated by the more-than-human world — yet by the phrase Abram also meant to encourage a new humility on the part of humankind (since the "more" could be taken not just in a quantitative but also in a qualitative sense). Upon introducing the phrase as the central term for "nature" in his 1996 book The Spell of the Sensuous (subtitled Perception and Language in a More-than-Human World), the phrase was gradually adopted by many other theorists and activists, soon becoming an inescapable term within the broad ecological movement.[7]

The publication of The Spell of the Sensuous[4] proved to be catalytic for the formation and consolidation of several new disciplines, especially the burgeoning field of ecopsychology (both as a theoretical discipline and as therapeutic practice), as well as ecophenomenology and ecolinguistics. Already translated into numerous languages, the first French translation of the text was completed by the eminent Belgian philosopher-of-science, Isabelle Stengers, in 2013.[14]

Since 1996, Abram has lectured and taught at universities throughout the world, while nonetheless maintaining his independence from the institutional world of academe. He was named by the Utne Reader as one of a hundred visionaries currently transforming the world,[15][16] and profiled in the 2007 book, Visionaries: The 20th Century's 100 Most Inspirational Leaders.[17] His ideas have often been debated (sometimes heatedly) within the pages of various peer-reviewed academic journals, including Environmental Ethics, Environmental Values and the Journal of Environmental Philosophy[18] In 2001, the New England Aquarium and the Orion Society sponsored a large public debate between Abram and distinguished biologist E. O. Wilson, at the old Town Hall in Boston, on science and ethics. (An essay by Abram that grew out of that debate, entitled "Earth in Eclipse," has been published in several versions.[19]) In the summer of 2005, Abram delivered a keynote address for the United Nations "World Environment Week" in San Francisco, to 70 mayors from the largest cities around the world.[20]

In 2006, Abram—together with biologist Stephan Harding, ecopsychologist Per Espen Stoknes, and environmental educator Per Ingvar Haukeland—founded the non-profit Alliance for Wild Ethics (AWE), for which he serves as Creative Director.[5] According to their website, the Alliance is "a consortium of individuals and organizations working to ease the spreading devastation of the animate earth through a rapid transformation of culture. We employ the arts, often in tandem with the natural sciences, to provoke deeply felt shifts in the human experience of nature. Motivated by a love for the more-than-human collective of life, and for human life as an integral part of that wider collective, we work to revitalize local, face-to-face community – and to integrate our communities perceptually, practically, and imaginatively into the earthly bioregions that surround and support them."[21]

In 2010 Abram published Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology,[3] which was the sole runner-up for the inaugural PEN Edward O. Wilson Award for Literary Science Writing,[22] and a finalist for the 2011 Orion Book Award.[23] A review in Orion by Potowatami elder Robin Wall Kimmerer described the book thus: "Prose as lush as a moss-draped rain forest and as luminous as a high desert night... Deeply resonant with Indigenous ways of knowing, Becoming Animal lets us listen in on wordless conversations with ancient boulders, walruses, birds, and roof beams. His profound recognition of intelligences other than our own enables us to enter into reciprocal symbioses that can in turn, sustain the world. Becoming Animal illuminates a way forward in restoring relationship with the earth, led by our vibrant animal beings to re-inhabit the glittering world,"[24] while in the UK, a review in the journal Resurgence said: "David Abram is a true magician, superbly skilled in both sleight-of-hand magic and the literary art of awakening us to the superabundant wonders of the natural world. He is one of America's greatest Nature writers... The language is luminous, the style hypnotic. Abram weaves a spell that brings the world alive before your very eyes."[25]

In 2014 Abram held the international Arne Næss Chair of Global Justice and Ecology at the University of Oslo, in Norway.[26] In that same year he became a distinguished Fellow of Schumacher College, where he teaches regularly.[27] He also teaches a weeklong intensive each summer on Cortes Island, in British Columbia.[28] Abram lives with his family in the foothills of the southern Rockies.[5]

See also[edit]

- American philosophy

- List of American philosophers

- Socio-ecological system

- Maurice Merleau-Ponty

- Animism

- Ecophenomenology

References[edit]

- ^ "Fellowships in Environmental Journalism". Middlebury College.

- ^ "IONS Directory Profile". Institute of Noetic Sciences. Archived from the original on 2013-02-04. Retrieved 2013-04-04.

- ^ a b "Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology By David Abram". penguinrandomhouse.com. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ a b "The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World By David Abram". penguinrandomhouse.com. Retrieved August 6,2020.

- ^ a b c d "David Abram". Alliance for Wild Ethics. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ See the papers and essays by Abram published on Academia.edu.

- ^ a b See, for example, its use within many papers in the Journal of Environmental Humanities, or the centrality of the phrase for recent textbooks such as Ecological Ethics: An Introduction by Patrick Curry (Polity, 2011) or Invisible Nature: Healing the Destructive Divide between People and the Environment, by Kenneth Worthy (Prometheus Books, 2013), or many more recent works like Being Salmon, Being Human by Martin Lee Mueller (Chelsea Green, 2017), Kabbalah and Ecology: God's Image In The More-Than-Human World by David Mevoroch Seidenberg (Cambridge University Press, 2016), Being Together in Place: Indigenous Coexistence in a More Than Human World by Soren C. Larsen and Jay T. Johnson (University of Minnesota Press, 2017), Participatory Research in More-than-Human Worlds edited by Michelle Bastian, Owain Jones, et al. (Routledge, 2016), "Locative Texts for Sensing the More–Than–Human" by Alinta Krauth (Electronic Book Review: Digital Futures of Literature, Theory, Criticism, and the Arts; May 2020) and innumerable other papers and books, "Routledge Handbook of Ecocultural Identity" edited by Tema Milstein and José Castro-Sotomayor (Routledge, 2020).

- ^ See Abram's afterword for Material Ecocriticism, edited by Serenella Iovino and Serpil Oppermann (Indiana University Press, 2014)

- ^ Abram, David (1996). The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-than-Human World. Vintage Books / Random House. pp. 63–85.

- ^ See, for example Material Ecocriticism, edited by Serenella Iovino and Serpil Oppermann (Indiana University Press, 2014), Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, Stone: An Ecology of the Inhuman (University of Minnesota Press, 2015)

- ^ London, Scott. "The Ecology of Magic: An Interview with David Abram". scott.london. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ Abram, David (1985). "The Perceptual Implications of Gaia - David Abram". academia.edu. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ "Stony Brook University College of Arts and Sciences: Department of Philosophy: Placement". stonybrook.edu. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ Stengers did the first full translation, which then was honed by her colleague, the Belgian bioregionalist and artist Didier Demorcey, and was published in France as "Comment la terre s'est tue: Pour une écologie des sens (La Découverte, 2013).

- ^ See "100 Visionaries," Utne Reader, Jan/Feb 1995; and "The Loose Canon: 150 Great Works to Set Your Imagination On Fire," Utne Reader, May/June 1998.

- ^ "David Abram". utne.com. January 1995. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ Whitefield, Freddie; Kumar, Satish, eds. (2007). Visionaries: The 20th Century's 100 Most Inspirational Leaders. Chelsea Green.

- ^ See, for example, Ted Toadvine, "Limits of the Flesh: The Role of Reflection in David Abram's Ecophenomenology" and David Abram, "Between the Body and the Breathing Earth: A Reply to Ted Toadvine" in Environmental Ethics, summer 2005 issue. See also Eleanor D. Helms, "Language and Responsibility" in the Spring 2008 issue of Environmental Philosophy. See also Meg Holden, "Phenomenology versus Pragmatism: Seeking a Restoration Environmental Ethic." Spring 2001 issue, and Abram's reply in the Fall 2001 issue, as well as Steven Vogel, "The Silence of Nature" in Environmental Values 15:2, 2006, and Bryan Bannon, "Flesh and Nature: Understanding Merleau-Ponty's Relational Ontology" in Research in Phenomenology, Volume 41, Issue 3, 2011.

- ^ Abram, David. "Earth in Eclipse: an Essay on the Philosophy of Science and Ethics". wildethics.org. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ See "United Nations Keynote" on the website of the Alliance for Wild Ethics: https://wildethics.org/united-nations-keynote/ Retrieved 2018-05-18.

- ^ https://wildethics.org/the-alliance/ Retrieved 2020-07-04.

- ^ "Book awards: PEN/E. O. Wilson Literary Science Writing Award". librarything.com. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ Triolo, Nick. "Becoming Animal is a 2011 Orion Book Award Finalist". orionmagazine.org. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ Kimmerer, Robin Wall (2011). "Finalist: Becoming Animal, by David Abram". orionmagazine.org. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ Harding, Stephan. "Saturated With Soul". resurgence.org. Retrieved August 6,2020.

- ^ "2014: David Abram". UiO: Centre for Development and the Environment. March 22, 2014. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ "David Abram". schumachercollege.org.uk. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ "Falling Awake: The Ecology of Wonder With David Abram". Hollyhock.ca. Retrieved August 6, 2020.