Confucianism as a Religious Tradition:

Linguistic and Methodological Problems1

Joseph A. Adler

Kenyon College

Gambier, Ohio, USA

Presented to the Institute for Advanced Studies in Humanities and Social Sciences (National

Taiwan University, Taipei) and the Department of Philosophy (Tunghai University, Taichung)

2014

This paper is an attempt to sort out some of the semantic difficulties in judging whether or not the Confucian tradition can or should be considered a religion, a religious tradition, or neither. I will focus on three sets of problems:

(1) the question of defining both "Confucianism" and "religion;"

(2) the distinction between "institutional" and "diffused" religion; and

(3) problems introduced by the Sino-Japanese translation of the Anglo-European words for "religion" (宗教 / zongjiao / shūkyō).

The religious status of Confucianism has been controversial in Western intellectual circles since the Chinese Rites Controversy of the 17th century. When Matteo Ricci argued that ancestor worship by Chinese Christian converts should be accomodated by the Church because it was only mere veneration, not true worship, he was obviously assuming a Western (or Abrahamic) model of religion. He and later missionaries searched for "God" and other signs of revelation in the Chinese scriptures; they argued whether Shangdi 上帝 (High Lord) or Tian 天 (Heaven) fit the bill, and whether Chinese "natural theology" was compatible with Christian revelation. In 1877 James Legge, the great missionary-translator, shocked the Shanghai Missionary Conference by averring that the Confucian (and Daoist) scriptures were alternative ways of reaching ultimate truths. His view, however, was based on the erroneous belief that buried beneath the Chinese tradition was an obscured monotheistic revelation, reflected, for example, in the worship of Shangdi and Tian.2

1 This paper was originally presented in slightly shorter form under the title "Confucianism as

Religion / Religious Tradition / Neither: Still Hazy After All These Years" at the 2006 Annual

Meeting of the American Academy of Religion in Washington, D.C.; and again in 2010 at the Institute of Religious Studies, Minzu University of China in Beijing. It has been revised again for this presentation.

2 See Norman J. Girardot, The Victorian Translation of China: James Legge's Oriental Pilgrimage (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002): 214-228.

Legge and the forerunners of the field of religious studies (e.g. Max Müller) included Confucianism in their understanding of "world religions." But throughout most of the 20th century the predominant view was that Confucianism was not "really" a religion, at least in the same sense as the more familiar (mainly Western) traditions. The majority of North American scholars in Confucian studies today take it for granted that the religious dimensions of Confucianism are abundantly evident. Yet, despite the growing sophistication of non-Eurocentric theoretical understandings of religion since the late 20th century, there is still widespread disagreement on the issue in the field of religious studies at large, and even more so in other academic fields. Many historians of East Asia, for example, still uncritically assume a Western model of what constitutes religion and exclude Confucianism from that category.

Definitional issues

Aside from the obvious necessity of defining the terms of our discussion, there are particular circumstances involving the Confucian tradition that require clarification. First is the fact that the name of the tradition in Chinese does not include a reference to the historical Master Kong (Kongzi 孔子), except insofar as the Western term in modern times has been translated into Chinese. (Kang Youwei used the term "Kongjiao" in the early 20th century to suggest the parallel with Christianity.) The followers of Confucius were called ru 儒, althogh the semantic range and intent of that term varied throughout the Warring States period. It originally meant "weak" or "pliable, " perhaps referring to the dispossessed members of either the defeated Shang people or the "collateral members of the Zhou royal family who had been disinherited after the breakdown of the feudal order in 770 BC[E]." By the end of the period, though, the meaning had more or less settled on something like "scholars" or "literati" or "classicists," and had come to refer specifically to the followers of Confucius. The teaching or Way (dao 道) of the ru focused on Confucius, the earlier "sages" (shengren 聖人) he venerated, and (importantly) the texts associated with them all. Mencius referred to that tradition as the "Way of the Sages" (shengren zhi dao 聖人之道). But since the late Warring States period the primary names for the tradition have been rujia 儒家 (the ru school of thought, or individuals in that category) and rujiao 儒教

(literally the teaching of the ru, but suggesting Confucianism as a religion because of the parallel with Buddhism as fojiao and Daoism as daojiao). Ruxue is yet another term, referring not to the tradition per se but to Confucian learning or scholarship.

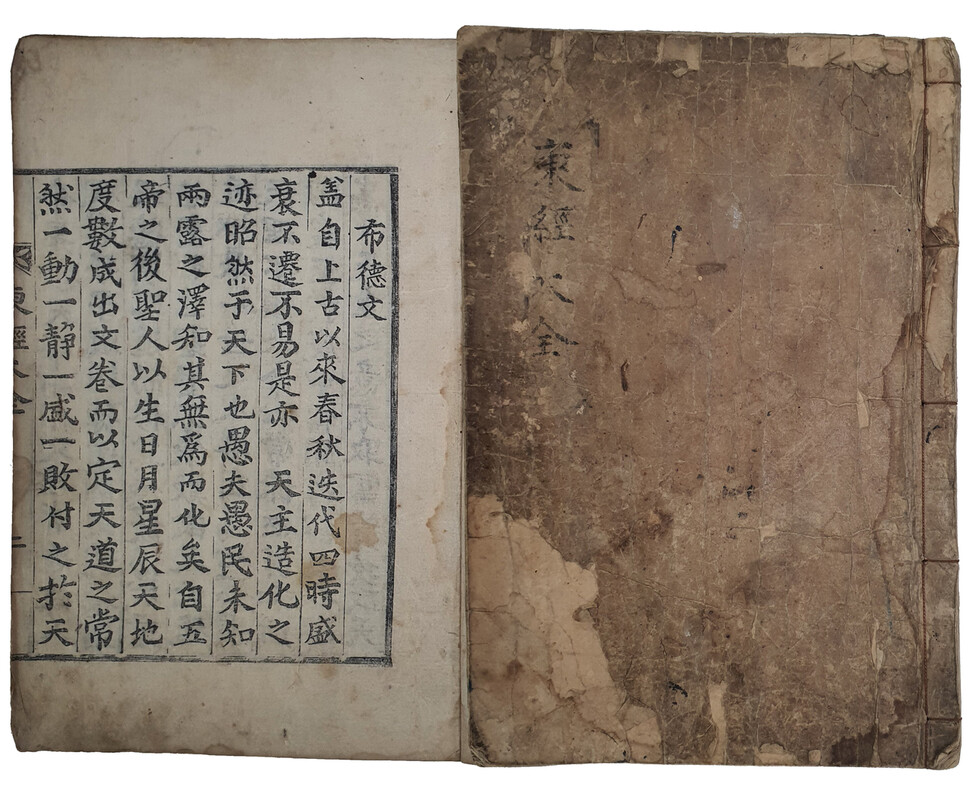

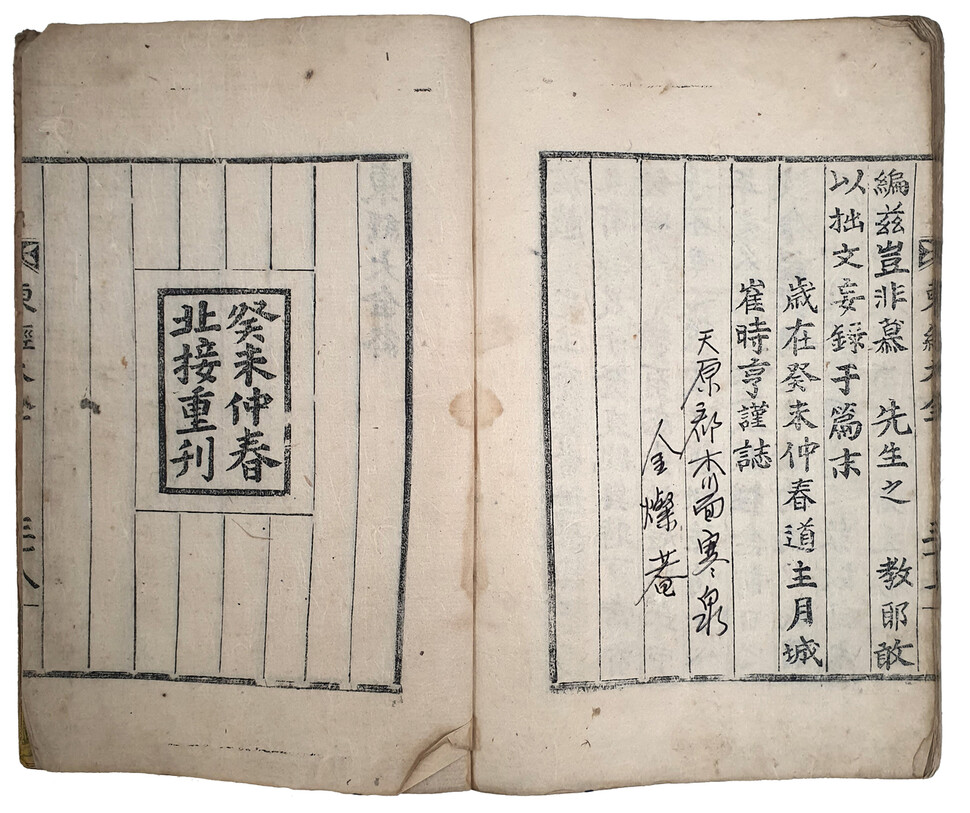

The ru came to be known as the experts in and custodians, as it were, of the cultural traditions embodied in the "Five Scriptures " (wujing 五經) and "Six Arts " (liuyi 六藝). An important corollary is that the term ru clearly implies literacy. So from the beginning, the ru tradition was limited to the literati; it could therefore never become a religion of the masses like Buddhism or Christianity. This is not to deny that elements of Confucian thought and values permeated nearly all levels of Chinese society throughout the imperial period (and beyond). But as a comprehensive religious worldview it is, for the most part, limited to literate intellectuals; it is, pre-eminently, a religion for scholars or intellectuals.

By the Song period, ru were clearly understood to be the literate followers of the

Confucian-Mencian tradition, as opposed to followers of the Buddha, who were usually called shi 釋 (from Shijiamouni 釋迦牟尼, or Śākyamuni), and Daoist adepts (daoshi 道士). In addition, the term daoxue 道學 (learning of the Way), used at first by the Cheng-Zhu school to refer to themselves, eventually came to be roughly equivalent to what has been called in the West "neo-Confucianism," or the revived and reconstituted Confucian tradition that took shape from the Song through the Ming periods. While there are some problems with this term, we can at least be confident that what we designate by the terms "Confucianism" and "Neo-Confucianism" are pretty much equivalent to what in Chinese have been called rujia / rujiao since the Han and daoxue since the Yuan. So this is not so much a problem as a cautionary indication that problems of translation may be involved.

Another problematic aspect of the term "Confucianism" is the question "which Confucianism?" The English term "Confucianism" is a tidy umbrella-term, suggesting a single, more-or-less unified tradition. But as just mentioned, in Chinese we have three terms (rujia, rujiao, and ruxue), all with slightly different connotations. There is also the fact that the Confucian tradition looks quite different depending on whether we are looking at theory or practice. From the 2nd century BCE to the end of the imperial period Confucianism was the official ideology of government in China. This was primarily manifested in the state sponsorship of Confucian texts (the so-called "classics," more accurately called "scriptures") during and after the Han, and the use of Zhu Xi's teachings as the authoritative basis of the civil service examinations beginning in the Yuan dynasty. In terms of practice or application, this resulted in a synergy that supported a hard conservative turn, since governments tend to have a strong stake in preserving social order. For this reason, Confucianism in China became to a great extent the ideology of preserving the status quo and reinforcing social hierarchy. There was also a theoretical component to this shift, resulting largely from Dong Zhongshu in the 2nd century BCE, and reflected, for example, in the Bohu tong 白虎通 (Comprehensive Discussions in the White

Tiger Hall) of 79 CE. This text reflects the conservative trend that, over centuries, would draw Confucianism consistently toward support of stability, a hierarchical order, and the status quo, especially in its statements about women. This "politicized Confucianism" cannot be ignored, but neither should it obscure the fact that there was also, especially from the Song dynasty onward, a strong "spiritual" tradition within Confucianism, whose followers aimed at perfecting themselves and perfecting society. So what we count as Confucianism should not be limited to its manifestation as a conservative ideology.

While the definitional problems surrounding the term Confucianism can be sorted out fairly easily, defining religion seems to be a never-ending process. In fact, the very use of the categories "religion" and "religions" has increasingly been called into question. Recent scholars have taken up Wilfrid Cantwell Smith's seemingly audacious claim, in 1963, that "[n]either religion in general nor any one of the religions ... is in itself an intelligible entity, a valid object of inquiry or of concern either for the scholar or for the man of faith." Jonathan Z. Smith, in a similar vein, claimed in 1982 that "religion is solely the creation of the scholar's study" and "has no independent existence apart from the academy." The argument of the two Smiths is that "religion" as a general category is merely a construct arising from the particular social and historical circumstances of the modern West, and were never conceptualized as distinguishable entities. In Buddhist terminology, neither religion in general nor any specific religion has any "own-being" (svabhāva) or "self-nature" (zixing 自性) and so all statements about religion or religions are statements about nothing. To ask whether Confucianism is a religion is therefore wrongly put on both counts, in their view: there's no such thing as Confucianism and there's no such thing as religion. In W.C. Smith's oft-quoted remark, "the question 'Is Confucianism a religion?' is one that the West has never been able to answer, and China never able to ask" (because the modern Chinese word for religion, zongjiao 宗教, was not coined until the late 19th century -- a point to be discussed shortly).

More recent scholars have stepped back from this brink of disciplinary self-destruction and have successfully refuted W.C. Smith's claim that the pre-modern absence of the modern Chinese word for "religion" prevented the Chinese from thinking about religion. Robert Campany, in a 2003 article in History of Religions, has shown that there are certainly Chinese terms, dating back to classical times, analogous to our various "isms." Chief among these have been dao 道, or "way, " in earlier periods and jiao 教, or "teaching, " in later periods (but considerably before western influence). The term sanjiao 三教, or "Three Teachings, " dating from the Tang dynasty, is clearly an indigenous term referring to three distinguishable things (Rujiao, Daojiao, Fojiao) belonging to one distinguishable category. And for our purposes the fact that one of those things corresponds to what we call "Confucianism" and the other two to what we call "Buddhism" and "Daoism" is, of course, significant. Clearly Confucianism was playing in the same league as Buddhism and Daoism, so it must have been playing the same game (as Ninian Smart used to put it).

Still, there remains the question: what is the game? This brings us back to the hoary problem of defining religion, which I will not discuss at length here. But it is important to note that referring to religion in general does not necessarily imply that such a thing exists apart from specific actors, institutions, or traditions. What we are trying to define is the characteristics or qualities that distinguish some actors, institutions, and traditions as "religious" from others that are not religious. We can ask that question meaningfully without falling into the trap of reification.

The most important point, especially in regard to Chinese religions, is to have a culture-neutral definition. Yet it is still not unusual to find statements to the effect that "while Confucianism may contain religious dimensions, it is not a religion in the Western (or usual) sense of the word." This, obviously, will not do. With the proviso that we need not think of any single definition as universally appropriate, but rather as a provisional way of shedding light on one or more aspects of the multi-dimensional set of phenomena we call "religious," I will note that many scholars have found Frederick Streng's definition of religion to be especially suitable to

Chinese religions. Streng said that religion is "a means to ultimate transformation," where "ultimate" can be understood in whatever terms are appropriate to the tradition. This is, therefore, a formal, culture-neutral definition. In the case of Confucianism, the goal of Sagehood is the endpoint of that transformation, and Heaven symbolizes the ultimacy that makes it religious. "Transformation" not only characterizes the process by which human beings become Sages (or fully humane, ren 仁); it is also a characteristic of the Sage, who "transforms where he passes" (Mencius 7A.13). The Sage, through his de 德 or "moral power, " transforms others and society itself. So by this definition -- one that focuses on what we might call the "spirituality" of the Confucian tradition -- it is not difficult to justify referring to Confucianism as a religious tradition.

Institutional and Diffused Religion

C. K. Yang's distinction between institutional and diffused religion is most helpful in understanding Chinese popular (or local) religion (minjian zongjiao 民間宗教).17 The distinction hinges on the social setting of the practices in question: institutional religion is practiced in a specifically religious social setting, such as a temple or monastery operated by clergy (priests or monks); diffused religion is practiced in a "secular" social setting: one that is not specifically religious, such as the family, community, or state. The case of local community temples is somewhat ambiguous, as Daoist priests usually conduct formal rituals in them, such as the community jiao 醮 ritual, or specific rituals requested and paid for by families or individuals.

But these temples are operated by the local, non-clerical community, and so would primarily fall into the "diffused" category.

The question for us then becomes, what is the social setting of Confucian practice? What, indeed, are the varieties of Confucian practice? It is customary to identify Confucian practice on the levels of the individual, the family, the community, and the state (the last primarily in imperial times). On the level of the individual there is the work of self-cultivation (gongfu 工夫), such as study, self-reflection, and (for some, especially after the Song dynasty) meditation in the form of "quiet-sitting" (jingzuo 靜坐). In the family and clan, or lineage, there is filial behavior and ancestor worship; these, of course, are practiced as well by people who do not self-identify as Confucians. Corresponding to practice at the level of the community in popular religion is the private Confucian school or academy -- again, especially after the Song. Since Confucianism is a tradition for literati (or, today, intellectuals), the academy is the natural social setting for it. The Confucian academies that flourished from the Song through the Qing periods in China -- not to mention those in Korea and those few that are beginning to reappear in the PRC, such as Jiang Qing's "Yangming Retreat" (陽明精舍) -- were central to the self-identification of avowed

Confucians. In addition to being places of learning -- and Confucian learning, of course, is learning to be a Sage, which, as noted above, is a religious goal -- there were also daily ritual observances, including prayers to Confucius and other sages and worthies. On the state level, before 1911 there were the imperial rituals at the Confucian temple, which fell into the "middle" category of state sacrifices. The "great" sacrifices were those to Heaven and Earth, which are

between spirit or mind and body, because the category of qi 氣 covers the entire spectrum from matter to energy to spirit. See my"Varieties of Spiritual Experience, " loc. cit.

17 C.K. Yang, Religion in Chinese Society: A Study of Contemporary Social Functions of Religion and Some of Their Historical Factors (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1961), ch. 12.

often loosely put under the Confucian umbrella, although that usage needs to be defended.

All four levels of Confucian practice -- the individual, the family, the academy, and the state -- are primarily "secular," so Confucianism can be considered an example of "diffused" religion. This is one of the reasons why it is so difficult to speak of Confucianism as "a religion." To call Confucianism a religion implicitly reifies the phenomenon as a distinct "thing," yet as diffused religion Confucianism does not exist separately and apart from the secular social settings in which it is practiced. The same difficulty applies to popular religion: we do not call popular religion "a religion, " because it is really a large and locally-variable set of religious practices. The inadequacy of such reificationist language is one of the factors that Tu Weiming was referring to when he wrote:

The problem of whether Neo-Confucianism is a religion should not be confused with the more significant question: what does it mean to be religious in the Neo-Confucian community? The solution to the former often depends on the particular interpretive position we choose to take on what consitutes the paradigmatic example of a religion, which may have little to do with our knowledge about Neo-Confucianism as a spiritual tradition (my emphasis). The problem of the reification of "religion" and particular "religions" was central to Wilfrid Cantwell Smith's argument that these terms refer to nothing and have no equivalents outside the modern West. As we have seen, there are, in fact, analogous terms in pre-modern Chinese usage for both the general and specific categories religion and religions . Yet an entirely new set of problems was introduced when the Japanese coined a neologism for the general category in the early years of the Meiji Restoration.

Translating "religion"

After the Meiji Restoration of 1868, the Japanese translators of Western texts and treaties explored a variety of options for rendering the word "religion" and its European equivalents. A few of these options, cited by Anthony Yu, were shinkyō / shenjiao 神教 (spiritual teaching), seidō / shengdao 聖道 (holy or sagely way), and simply kyō / jiao 教 (teaching). The

Japanese eventually settled on shūkyō / zongjiao 宗教 (ancestral teaching), which they appropriated from Chinese Buddhist usages going back at least to the 6th century. In Buddhist usage zongjiao usually meant simply the teachings of a particular school or sect (zong 宗); it was also used in the sense of "revered teaching, " sometimes in reference to Buddhist doctrine as a whole.

Yu argues that the choice of a kanji (Chinese) term bespeaks a deliberate suggestion of "cultural otherness," consistent with the fact that the prime example of "religion" in question in the texts being translated was Christianity. And Christianity was not only a foreign religion; it was a religion that differed in important respects from Shinto and Buddhism. First, it was a religion that demanded exclusive membership, which was vastly different from the usually comfortable coexistence and syncretism of Shinto and Buddhism in Japan. Second, Christianity placed a great deal more emphasis on belief in doctrines than did either of the Japanese religions, which have always focused more on action than on belief (and this generalization applies equally well to Chinese religion). Both of these characteristics are reflected in the binome shūkyō: shū (zong

宗) carries the connotation of separateness, as it is the word that denotes the individual schools or sects of Buddhism (e.g. Zenshū, Tendaishū; kyō (jiao 教) connotes doctrine. According to this line of reasoning, shūkyō was deliberately coined to denote something alien to Japanese culture, and when it was picked up by the Chinese shortly thereafter it carried much the same flavor.

Peter Beyer suggests that another connotation of the zong in zongjiao is organization, and that it is this characteristic of Daoism and Buddhism -- i.e. the fact that they are institutional religions in C.K. Yang's sense -- that renders them good examples of the general category of religion. Organization, he says, "is the prime factor through which religions express their difference, from each other and from matters non-religious." He quotes a statement by Wing-tsit Chan, in the context of a discussion of Kang Youwei's attempts to make Confucianism the state religion of the early Republic of China:

All these arguments, reasonable and factual as they are, can only lead to the conclusion that Confucianism is religious, but they do not prove that Confucianism is a religion, certainly not in the Western sense of an organized church comparable to Buddhism and Taoism. To this day, the Chinese are practically unanimous in denying Confucianism as a religion.

Chan's willingness to count Buddhist and Daoism as religions is clearly based on their institutional organization. Confucianism, being a diffused religion, does not qualify; but it "is religious." The distinction between a "religious tradition" and a "religion" is therefore not as trivial as it may appear. In the case of Confucianism, calling it "a religion" does not work because it is an example of diffused religion, like popular religion in China -- which also resists being called "a religion." Yet both are clearly religious. Adding to this problem is the fact that

Confucianism is basically non-theistic. While Heaven (tian) has some characteristics that overlap the category of deity, it is primarily an impersonal absolute, like dao and Brahman. "Deity" (theos, deus), on the other hand connotes something personal (he or she, not it).

To summarize, much of the "problem" of the religious status of Confucianism centers on the terminology we use in reference to religion and religions. It is not difficult to agree on a "definition" of religion that is capable of illuminating certain aspects of the Confucian tradition in a "religious" light. The problem seems rather to arise when we try to call Confucianism "a religion." The reason for this problem is that "a religion" implies an institutional entity, analogous to a church, and Confucianism is in fact a "diffused religion" whose social base lies in the "secular" realm, in the social institutions of family and the academy. Furthermore, Confucianism is non-theistic. Buddhism is also non-theistic, but it is institutional. So the two most common connotations of "religion" – belief in God or gods and an institutional base – are missing from Confucianism. This, I believe, is why so many people in both the West and East Asia resist calling Confucianism "a religion." So, just as we do not refer to Chinese popular religion as "a religion" because it lacks an organized, institutional base, so too we should recognize that the question "Is Confucianism a religion?" is wrongly put. The better question is, as Tu Weiming suggested, "Is Confucianism a religious tradition?" Although it is important to note that

Confucianism has not always and everywhere been practiced as a religious tradition, as a general statement the question can be answered affirmatively without raising any serious problems.

The suggestion that we refer to Confucianism as "a religious tradition" (zongjiao xing de chuantong 宗教性的傳統) rather than "a religion" (zongjiao 宗教) may sound trivial, especially since there is already such a trend in English-speaking academia. English-speaking scholars increasingly use terminology like "Christian tradition" instead of "Christianity" precisely to avoid reifying or essentializing the tradition. But to make this shift in usage more self-conscious and deliberate would be consistent with Robert Campany's suggestion to think and speak of religions as "repertoires of resources" that are "used variously by individuals negotiating their lives." A "tradition" can be conceived as a repertoire (or "tool-kit") in that what the previous generation chooses to hand down is selectively passed on to the following generation. In focusing on the act of "handing down" and the choices involved therein, the notion of a religious tradition shifts the language toward a more process-oriented way of thinking about religion, thereby weakening the tendency to reify religion and religions that W.C. Smith identified.

To be sure, Smith's own prescription for avoiding the problems of reification also involved the language of "tradition:" he said that we should replace our "religion" language with the language of "personal faith" and "cumulative tradition." "Faith," however, carries too much Western, especially Christian, baggage, and it privileges belief and doctrine over action. This renders Smith's model unsuitable for both Chinese and Japanese religion, and therefore unsuitable as a general model. Smith may have formulated the question for us, but we are still working on the answer.

Confucianism indeed challenges us to critically examine our own assumptions and conceptual framework, including both the western concept of religion and the Chinese concept of zongjiao. The first step is to understand the difference between these two terms. Although zongjiao is the direct translation of "religion, " it does not carry precisely the same connotations as the English term, as we have seen. Another step is to reexamine the conceptual dichotomy of "sacred and profane," as developed by Émile Durkheim, Joachim Wach, and Mircea Eliade. The concept of the sacred as that which is "set apart" from the mundane, secular world is generally considered, at least in Western academic circles, to be a common characteristic of all forms of religion. But Confucianism deconstructs the sacred-profane dichotomy; it asserts that sacredness is to be found in, not behind or beyond, the ordinary activities of human life -- and especially in human relationships. Human relationships are sacred in Confucianism because they are the expression of our moral nature (xing 性), which has a transcendent anchorage in Aheaven@ (tian 天). Herbert Fingarette captured this essential feature of Confucianism in the title of his 1972 book, Confucius: The Secular as Sacred. To assume a dualistic relationship between sacred and profane and to use this as a criterion of religion is to beg the question of whether Confucian can count as a religious tradition.

I therefore conclude that Confucianism is a non-theistic, diffused religious tradition that regards the secular realm of human relations as sacred. Being non-theistic it is like Buddhism. As diffused religion it is like Chinese popular religion. In regarding certain aspects of the mundane world as sacred it is like Tibetan Bӧn, Japanese Shinto, and other indigenous religious traditions. All of these points are part of the unique character of Confucianism and cannot be used a priori to exclude Confucianism from the general category of religion.