What I wish I knew Before Vipassana

An open letter to new (and old) students who wish to take a 10-Day Vipassana Meditation course, as taught by SN Goenka

A 10 day Vipassana Meditation course as taught by Goenka is intense, confusing, and often frustrating. Although I’ve now completed my third (twice as a student, once as a server), I’ve definitely had my days where I felt like walking out.

So, to help new students that have the aspirations of completing their first 10 day Goenka course (or even old students who want to give it another go), I have decided to lay out all of the things that I wish someone had told me before I took my first course. By going into it with a firm understanding of the below principles, you can focus on the practice, rather than trying to sort through the confusion and skepticisms. I believe that a little additional expectation setting and clarity can go a long way into making sure you get the most out of the experience.

I understand that this post might not be Goenka (or even Vipassana approved), but this is what I would tell to a close friend who is about to take a course. I hope that this helps you to get through it all with equanimity and come out with a smile 😃

*Disclaimer/Spoiler Alert — It’s a long post, but 10 days of silent meditation is a long course. Take your time to get through this. There are also a lot of spoilers in terms of what you will go through. If you want to go in blind and don’t want to know about the technique, I don’t suggest reading past this point.

1) It’s not a “retreat” — I often have people reach out to me and ask me about going on a meditation “retreat”. Vipassana is definitely not a retreat. It’s hard work. Treat it as such.

If you are going into a Goenka course with the intention of taking a vacation or relaxing, you’re in for a rude awakening. It is a course that has you working all day every day. When you sit down on that cushion, go into it with the intention that you are going to work on yourself, and you are going to work harder and push yourself more than you ever have in your life.

Don’t get me wrong, when you leave the course you will feel more refreshed, invigorated, calm and relaxed than you ever have in your life, but in order to get those results you have to work hard and come in with a serious attitude. It’s not a vacation or retreat, your work ethic should reflect this.

2) It’s a boxing match — Building on the above point, I treat every sitting session as a boxing match between myself and the habit pattern of my mind. Your mind will do ANYTHING it can to distract you from working. Unpleasant thoughts, feelings, and emotions will all rise and distract you from working as you should be. Don’t let your mind win. Patiently observe when your mind is trying to distract you, and do your best to get back to work. Some sessions you will win, other sessions you’ll get knocked out. This is normal. But get back in the ring and get back to work after each session.

3) Day by day schedule

The first three days of the course are spent in what is known as “Anapana”, which is essentially focusing all of your attention on your natural breath. Pay attention to the breath, mind wanders, bring it back to the breath. If you can focus for a minute straight, bravo. If you can only focus for a few breaths at a time, don’t get discouraged, this is absolutely normal. Even old students struggle to focus their attention for more than a minute at a time on only their respiration. At times it will feel like a ping-pong match in your head, this is a natural part of the process.

- Day 1: Focus on Breath

- Day 2: Focus on the feeling of your breath going in and out of your nostrils

- Day 3: Focus on any “sensations” or feelings that arise on your upper lip. This can be an itch, a tingle, the feeling of breath going into and out of your nose, heat, perspiration, coolness, dryness, any physical sensation you can feel. The sensation isn’t important, the observation and focus on it IS.

- Day 4: You learn the technique of Vipassana — Prior to this you were focusing on any sensations that arise on the area of the upper lip, now you will do this to your ENTIRE BODY. Top of the head, back of the head, sides of the head, forehead, eyebrows, nose, ears, cheeks, lips, jaw, neck, pectorals, biceps, triceps…and so on. Part by part. Piece by piece. From the top of your head down to your feet until you have examined every single solitary aspect of your body for any sensations that arise.

- Day 5: Scan from top of the head to the feet over and over looking for sensations. This is also when the Adhittana (strong determination) sittings begin. You will now sit for the full hour without changing positions/posture (if you can).

- Day 6: Scan from top of the head to the feet, and then from feet to the head

- Day 7: Scan both sides of the body at the same time. If you were previously scanning right side and then left (example right ear and then left ear), now you will try to do both at the same time, passing from the top of your head down to your feet, and then from your feet back up to your head.

- Day 8: At this point you may or may not have free flowing sensations throughout the body, making it easy to quickly scan from the top of the head down to the feet, and then back up. If you were previously moving slowly, now you can begin to move a bit faster. If you don’t have these free flowing sensations yet, not to worry, this is normal. Continue to scan part by part, piece by piece. If you have free flow in some areas, scan through those quickly, and if you have to go part by part for other parts of the body, this is fine.

- Day 9: If you’re experiencing gross subtle sensations free flowing throughout the body, you might be able to begin doing the “internal scans” where you penetrate from the front of your body through to the back, and then from the back to the front. Or penetrate from left to right, and then right to left. Personally this has never really clicked for me, so I don’t fully understand it yet.

- Day 10: You can begin talking again after the Metta session. Metta is Peace, Loving, Kindness meditation. This is my favorite session of the entire ten days. It’s beautiful, and then when it’s finished, you can talk again 😃

- Day 11: Morning session and then leave after breakfast.

***Note — Day 2 and day 6 are the hardest — especially day 6. Keep this in mind if you’re struggling on these days, it’s normal.

4) Common terms defined

There is often a lot of confusion about the words that Goenka uses. I personally believe that this is because they are directly translated from Hindi, and his English isn’t perfect, so some of it gets lost in translation. I have defined my understanding of the common words he uses as to minimize confusion and not get swept up in the semantics of what he talks about.

- Sensations = Physical Feelings — This can be an itch, a tingle, a chill, the touch of your clothes on your skin, heat, perspiration, coolness, dryness, pain, discomfort, pulsating, throbbing, or something you can’t quite describe. Sensations can be both pleasant (tingle/chill/subtle vibrations), or unpleasant (itch, pain,throbbing) Sensations are simply any physical feeling that arises on your body.

- Impermanence = arising and passing — All feelings or sensations that arise on the body are impermanent, they won’t last forever, and it will eventually pass. This is the law of nature, or what he refers to as “anicca”. As he says, “There’s no itch that lasts forever”. As is such with the human body. The body is constantly changing, and nothing is permanent. By observing sensations and feelings on the body arise and pass, we are witnessing the law of impermanence in action.

- Misery — He uses the word “misery” a lot, and I believe this is a bit extreme. I like to think of it as creating our own unhappiness or unpleasant/negative states of mind, and how to free oneself from these habits.

- Craving = Pleasure or pleasant experiences. When we experience something we like we usually say “I like this, I want more of it”, and when it doesn’t necessarily happen again, it causes us to become unhappy. This desire for pleasant feelings is what he refers to as cravings.

- Aversion = Unpleasant or unwanted feelings, things you want to go away. Things we want to avoid. When we experience something we don’t like, we will usually say, “I don’t like this, make it stop”, and in doing this we become averse to unpleasant or unwanted experiences and feelings.

- Equanimity = Non-reactivity — This is probably the most important word/teaching of the entire course. Remaining “equanimous” means to be able to observe both pleasant and unpleasant sensations and not react with craving or aversion. The ability to simply observe, and not react (which is the most difficult part). If a pleasant sensation arises it’s easy to say “whoa what the hell was that! That was cool!”, and if an unpleasant sensation like pain arises it’s easy to say “My leg is KILLING me right now!”, and then adjust your posture to try and alleviate the pain. Learning how to simply observe and not react is the learning how to remain equanimous. This also becomes an analogy for life, as the key to living a happy life is remaining equanimous and not reacting to the various up’s and down’s that we experience in our day to day lives.

- Sankaras = Habits or Reactions — My Assistant Teacher described Sankaras to me as “things that are repeated over and over by the mind, body, or speech. When repeated numerous times it becomes a habit.” When Goenka speaks of Sankaras rising to the surface, these are the habit patterns of the mind manifesting in the form of either cravings or aversions as feelings in the body. For example a part of your body with no sensations could be a Sankara of craving (because you want a sensation there and you aren’t getting it), or a sensation of pain could be a Sankara of aversion (because you want it to go away).

5) The practice/philosophy defined so you aren’t confused and can focus on sitting

To summarize the above, the philosophy/practice is defined as follows:

First we concentrate the mind. Once the mind is focused/sharp, you can begin to feel subtle sensations and feelings in the body you don’t normally feel. These sensations can be pleasant or unpleasant, but they key is to recognize that they are impermanent; they will eventually pass. The habit pattern of the mind is to react to pleasant sensations with craving, and unpleasant sensations with aversion. The key is to understand that sensations cause reactions. Learn to observe these sensations, and not react, because these sensations are impermanent and will eventually pass. This process of observation without reaction is referred to as developing equanimity.

By following this process, you essentially make yourself more sensitive to and aware of your feelings. In your everyday life, you will begin to notice that there is always a feeling or sensation that comes before a reaction. If you can, try to notice which feelings cause which reactions. If you can’t catch the feeling before the reaction, when you do react, try to notice how you feel, or how long it took you to notice the feeling ex) If you get angry, stop and try to pay attention to what sensations or feelings there are in the body. This attention to feelings will then help you in the future to notice when you are feeling a certain way, and remain equanimous rather than reacting.

6) If/when you ask the teacher questions — you will probably get vague answers — this is normal and don’t get frustrated, it’s a part of the practice. At first it’s frustrating because there’s a tendency to want a more robust answer, but there’s a method to the madness, and there’s normally great wisdom in these concise answers if you pay attention. No matter what my question is, the answer is usually something along the lines of “observe it and remain equanimous.”

7) The less you eat, the better — it’s hard to meditate while full. Eat the bare minimum — while you might get hungry at times, the overall practice will be better.

8) Progress is measured by your ability to remain equanimous and not react to both pleasant and unpleasant sensations — not how powerful the sensations are — As the days go on, sensations become easier to notice, and become more powerful. It’s easy to see this progression in sensations as progression in meditation, but this is not the case. Don’t play the “sensations game”. True progress is measured by your ability NOT to react to these sensations.

There’s also a tendency to have a good session and then want to repeat/replicate that previous session, and then if we can’t, we wonder why and think that we’re regressing and get frustrated — but that’s just craving. Realize that a good session might not ever happen again (it’s impermanent), and appreciate the moment for what it is, rather than trying to replicate it again. I’ve had sessions where my mind was lazer focused, only to have my concentration completely shot for the next two. Keep at it and remain equanimous.

9) 5 Enemies or Hindrances that will prevent you from focusing:

“

- Sensory desire (kāmacchanda): the particular type of wanting that seeks for happiness through the five senses of sight, sound, smell, taste and physical feeling.

- Ill-will (vyāpāda; also spelled byāpāda): all kinds of thought related to wanting to reject, feelings of hostility, resentment, hatred and bitterness.

- Sloth-torpor (thīna-middha): heaviness of body and dullness of mind which drag one down into disabling inertia and thick depression.

- Restlessness-worry (uddhacca-kukkucca): the inability to calm the mind.

- Doubt (vicikicchā): lack of conviction or trust. “

Taken from Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Five_hindrances

#5 was the biggest for me my first go around — I spent a lot of time in skepticism of the technique and the teachings of Goenka, instead of putting my reservations aside and giving thought to them at the end. When you’re in the course, you’ve already committed to it. See it through to the end and put your skepticism aside (but it will be tough). If you want to, give thought to the skepticism afterwards and decide which elements of the practice work best for you. Every moment is precious, don’t waste it doubting the technique.

10) 5 Friends that will help you in your practice:

“

- The first friend is faith, devotion, confidence. Without confidence one cannot work, being always agitated by doubts and skepticism.

- Another friend is effort. Like faith, it must not be blind. Otherwise there is the danger that one will work in a wrong way, and will not get the expected results. Effort must be accompanied by proper understanding of how one is to work; then it will be very helpful for one’s progress.

- Awareness. Awareness can only be of the reality of the present moment. One cannot be aware of the past, one can only remember it. One cannot be aware of the future, one can only have aspirations for or fears of the future. One must develop the ability to be aware of the reality that manifests within oneself at the present moment.

- The next friend is concentration, sustaining the awareness of reality from moment to moment, without any break. It must be free from all imaginations, all cravings, all aversion; only then is it right concentration.

- And the fifth friend is wisdom — not the wisdom acquired by listening to discourses, or reading books, or intellectual analysis; one must develop wisdom within oneself at the experiential level, because only by this experiential wisdom can one become liberated. And to be real wisdom, it must be based on physical sensations: one remains equanimous towards sensations, understanding their impermanent nature. This is equanimity at the depths of the mind, which will enable one to remain balanced amid all the vicissitudes of daily life.”

Taken from: http://www.gurusfeet.com/files/buddhism.-.s.n.goenka.-.vipassana.discourse.summaries.-.ocr_.version.1.pdf

11) Use cushions, it makes a huge difference — Pretty straightforward, but so important. Getting the right ratio of pillows will make a bit difference, especially if you have back problems. Personally, I like to be about 6–8 inches off the ground. Some people I’ve seen put cushions under their knees, but I don’t do this. I don’t recommend using a chair unless you have a serious injury. The likelihood of falling asleep in a chair is much higher.

12) Go to sleep during rest periods — If you have the chance to sleep, take it. My personal rhythm was to take a fifteen minute walk after breakfast and lunch, and then go to sleep for the rest of the break time. I didn’t sleep during the time after tea/fruits, but others did.

13) It’s painful — but the pain is necessary — One of the biggest complaints I’ve seen from others is that it’s very painful. Let’s face it, even if you’re an experienced meditator, sitting for 1–2 hours straight, for 10 total hours a day, is a lot. Especially when you get to the Adhittana (strong determination) sittings, where you’re not supposed to change posture for the full hour, it can become a lot to handle. I personally get a lot of pain in my knees, my feet frequently fall asleep/go numb, and my shoulders/back will be very sore once I get past day 5 or 6.

This one took me a while to understand, but once again it’s all about equanimity. Learning how to not react to sensations, especially the unpleasant ones. Goenka mentions that by learning how to not react, no matter how unpleasant the sensation is, we train our mind at the deepest level to remain equanimous…and it’s true. These sittings have become a cornerstone of my practice, and the stronger I become at not changing posture, the stronger my equanimity becomes as well. Pain is sometimes the best teacher of all 😉

14) If you can’t fall asleep at night, that’s normal — Once you get to day 6/7, if you can’t fall asleep, this is 100% normal, and is actually a good sign of progress. Goenka explains that we need sleep for 2 reasons — the body, and the mind. If you have been practicing well and making good progress, your subconscious mind is rested — so while your body needs the rest, your mind may not. If this happens to you, don’t worry. Continue to observe sensations while lying in bed and keep the equanimity flowing (easier said than done though).

15) Sankaras can hit you — and hard — don’t freak out — This is where things get a bit freaky. I’ve had ringing in my ears, my jaw locked up on me, thrown up, stomach aches… I’ve had some pretty violent Sankaras. I’m definitely an outlier of sorts here, and most of this doesn’t happen to people unless it’s a longer course, but it’s happened to me. I know I freaked out when it happened to me, so I don’t say this to scare you, I say this so that if something like this happens, you remain cool, calm, and collected, and realize that it’s impermanent — it WILL pass.

16) Enjoy it! Like everything else, the 10 days will fly by (no matter how long it seems at the time). Enjoy the experience and work hard. Goenka continually says that every moment is precious, and it’s true. Appreciate every moment you have there, because in the end it’s impermanent and will pass before you know it. Im eternally grateful for discovering this technique, and I couldn’t be happier with the changes I’ve seen in myself. I hope you have the same and I wish you the best of luck on your journey.

May all beings be happy! May all beings experience real peace!

Did you have a similar experience? Please comment below and share what you would add. The more we help each other, the better!

WRITTEN BY

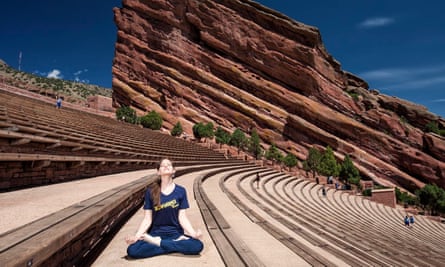

The author meditating: ‘A full 10 days of constant meditation created a barrier between the worrying and me.’ Photograph: Attit Patel for G Adventures

The author meditating: ‘A full 10 days of constant meditation created a barrier between the worrying and me.’ Photograph: Attit Patel for G Adventures The grounds of the mediation retreat near Auckland. Photograph: Jodi Ettenberg

The grounds of the mediation retreat near Auckland. Photograph: Jodi Ettenberg The ‘spider catcher’. Photograph: Jodi Ettenberg

The ‘spider catcher’. Photograph: Jodi Ettenberg